4. CULTURAL, LEGAL, AND ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

![]()

IN MY TRAVELS, I have experienced almost every potential reaction to my camera. From teenagers happily posing and insisting that I take their picture, to locals who deliberately turn their back on the irritating tourist with a camera (Figure 4.1). At this point in our technologically homogenous world, there are very few populations who believe the camera steals a piece of your soul, but that doesn’t mean that every culture out there is open to being photographed by a stranger.

Your travels are likely to introduce you to people who are wary of the camera. You may even encounter entire countries or regions where it is illegal to photograph without special permission. World travel means going outside your comfort zone and experiencing new cultural behaviors, and part of being a successful travel photographer (and a successful traveler in general) is preparing for a journey by researching the customs, laws, and ethics at play. Ideally you will have a good understanding of a culture’s general belief system, behavioral expectations, standards of attire, and view toward photography long before you set foot in a location, freeing you to enjoy your experience and minimizing any potential conflicts with locals or law enforcement.

Practice Photographic Stewardship

So why is it so important to know the rules ahead of time? Isn’t it easier to ask forgiveness than permission? Sure, you could potentially get away with photographing lots of things you’re not supposed to, but one photographic misstep or an argument with a local could cause a major headache and potentially ruin your feeling toward a trip or even an entire country.

4.1 The woman in yellow deliberately turned away from the camera. San Juan del Sur, Nicaragua

ISO 160; 1/160 sec.; f/6.3; 47mm

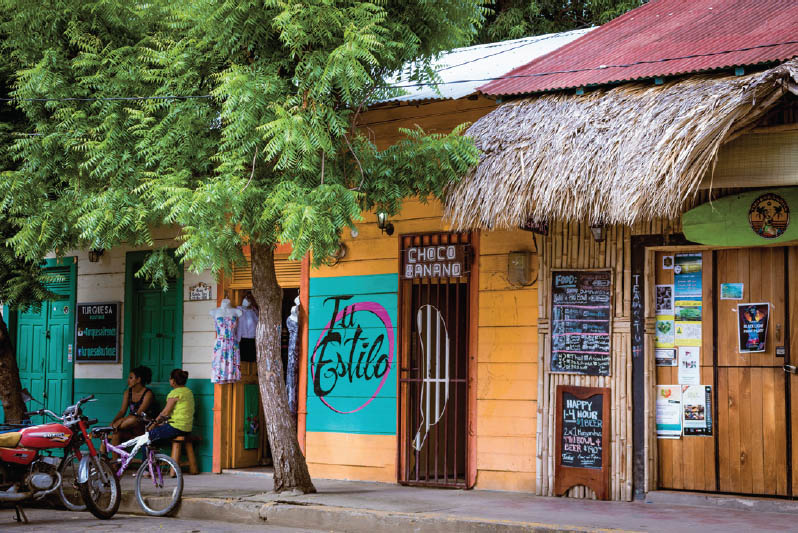

4.2 Granada, Nicaragua

ISO 100; 1/200 sec.; f/4.5; 24mm

My hope is that if you’re reading this, you want to be the right kind of travel photographer—the kind who seeks to leave the world better than they found it. I believe that photographers have an ethical responsibility of stewardship toward the subjects we photograph. That’s not to say that we must always portray a place or situation in a positive light or hide the gritty details from view. The world is filled with beauty, but there is no shortage of ugliness either.

When visiting Nicaragua, I felt an ethical dilemma about the street dogs that seemed present on every corner. As I fell in love with the culture, the architecture, and the general atmosphere of the country, the homeless dog population weighed on me. I struggled, wondering whether to include the dogs in my photographs (their presence seemed to amplify the notion of Nicaragua as a third-world country) or selectively frame my shots to exclude them.

Ultimately, I decided that telling the story of Nicaragua means telling the whole story as I experienced it. Omitting the street dogs felt dishonest, but focusing on them alone wouldn’t be an accurate depiction of reality either. I settled on a realistic dose of stray dog. If I framed a picture and a dog was in the composition, then I let it stay (Figures 4.2 and 4.3), but if there wasn’t one in sight, I didn’t seek one out. The stray dogs add interest to my travel photographs, telling the candid story of a developing nation.

Above all else, your images should be true to your experience. In the Internet age, it is important to remember that exploitative or irresponsibly acquired images have the possibility of being seen by many and could influence far more than just your own opinion of a place or situation. So before you travel, research the potential ramifications of your actions as a documentarian and gain permission when necessary.

4.3 San Juan del Sur, Nicaragua

ISO 100; 1/200 sec.; f/4.5; 24mm

Photographers’ Rights in the US

In the United States, we have fairly clear-cut laws about photographing in public:

- You can shoot anything in any public location, including visible private property.

- You cannot shoot on private property once asked to stop or if there are posted signs forbidding photography.

- You can photograph people in public without their consent, unless their location gives them reasonable expectation of privacy.

- In public, it’s usually legal to shoot the following: fires, accidents, police, criminals, celebrities, children, infrastructure, public utilities, transit hubs, homes, stores, factories, and bridges. Military buildings are traditionally off limits.

- You don’t have to explain your purpose or show identification (unless asked by a police officer in some states).

- Private parties can’t harass you, detain you, or confiscate or damage your film or digital files. Police need court orders to take your property or delete your images.

If you’re interested in getting more specific information about photographers’ rights in the US, attorney Bert Krages has made a downloadable PDF available on his website (www.krages.com). I keep a copy in my camera bag and am very assertive when it comes to protecting my civil liberties as a photographer. This gets significantly trickier when you plan an international excursion.

Photographers’ Rights Abroad

When planning a trip to a new country, take the time to find out:

- Is it illegal to photograph people without their explicit permission? (The photograph in Figure 4.4 is perfectly legal in the US, but might be less acceptable in other locations.)

- Is it legal but culturally frowned upon?

- Is it acceptable to photograph children without parental consent?

- Are there any religious considerations that you need to prepare for?

- Are there any current human-rights or animal-rights issues that your photographs could potentially highlight or relate to?

- Will you be photographing an endangered animal or a protected ecosystem?

- Do you need any specific permits or licensed guides to access an area?

Answers to these questions aren’t always easy to come by, but like most things photographic, a quick Google search can get you on the right track. Other potential resources include the CIA World Factbook, locally run tourism agencies, foreign copyright acts, and WikiMedia Commons, which maintains a country-specific list of consent requirements.

Model releases are a valuable asset if you plan to sell or publish your work in the future. Many photography contests, magazines, and stock agencies require a model release even if the image was taken under circumstances in which a release was not legally required. Ideally, you should always present model releases to subjects in their own language, but I wouldn’t recommend just plugging an English-language release into Google Translate. On their website, Getty maintains a list of downloadable foreign-language model releases. If you want to keep things digital, Easy Release – Model Release App is a great paid app that will translate your release into a number of languages and allow models to sign on your phone or tablet.

4.4 Riverhead, New York

ISO 500; 1/160 sec.; f/3.5; 18mm