Leadership in school, public, and academic libraries in the US, the UK, Canada and Australia

Abstract:

School, public, and academic libraries are the focus of this chapter. While all three library sectors have always had funding issues, and more so now since the 2008 economic crunch, school and public libraries are the most affected by budgets with regard to staff, collections, and technology upgrades. These are the two sectors that either close their doors permanently or stay open with reduced hours and fewer services. It is also these two sectors in which leadership literature is in short supply. From the leadership literature available, it is evident that all three library sectors are interested in doing something or other to improve their libraries and, most importantly, also interested in doing something towards building leadership in their libraries in spite of the political and economic issues.

Much of the literature available on library leadership, regardless of the sector (public, school, or academic) focuses on the lack of leadership initiatives and the issue of librarians still being hesitant about leadership in libraries. In 2001, Riggs challenged librarians to name three library articles with leadership in their titles (ibid.: 8). In the same year Glegoff (2001: 79) worried that “without skillful leadership from library administrators to pilot a course through the enormous challenges” it is doubtful “that libraries will retain the esteem traditionally held for them by the public.” In 2005, Mullins and Linehan found librarians in their survey articulating that “many head librarians are not making that changeover from librarians to leaders” (ibid.: 392) and that “leadership never featured highly in librarianship before” (ibid.). In 2003, the Demos article found that “leadership was the most frequently cited development need identified in the stakeholder interviews “ (ibid.: 19). In the same year, Black found that some of the major library databases retrieved depressing results on a search of leadership. He speaks of Proquest, Expanded Academic Index, Australian Library and Information Science Abstracts (ALISA), the Australian Library Journal (ALJ) and the Australian Computer Society (ACS) (Black, 2003: 454–455). It is even more depressing to try and find anything on ethnic-minority leadership. More articles and books have been written on leadership for librarians since Riggs’ challenge, but there is the question of whether it is being practiced. As Riggs says, since “there is no more powerful engine driving a library toward excellence and success than its leadership” (Riggs, 1998: 8) so librarians from all sectors need to focus on leadership issues for their organizations.

Acree et al. (2001) speak of the under-representation of librarians and give some reasons as to why. Minorities are frustrated with the glass ceiling in the profession and feel marginalized because they are hired at entry-level positions and there is a lack of movement beyond that. He cites Howland (1999) who pointed out the problem. The problem was not in hiring minorities into the profession but in helping them move ahead by recognizing their skills and potential. This problem has its roots in library schools. There are not enough minority students in library schools and therefore not enough to enter the profession. And when they leave out of frustration there are even less of them available for leadership positions. With first generation immigrants, their education from within their home countries is not always recognized, which only makes it more challenging and frustrating for them to enter the library profession.

School libraries and leadership

In the US, a library service to schools began around the 1800 s when book wagons delivered books to schools (Michie and Holton, 2005: 2). It wasn’t until Congress passed the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965 that money was set aside for school libraries and only then were libraries viewed as an integral part of schools (ibid.: 3). The launch of Sputnik by Russia caused an urgency in creating better schools and out of this evolved the concept of good school libraries staffed by proper personnel. But both then and now school libraries have had to compete for funding at the local and state levels with many other programs. As Hopkins and Butler (1991: 34) state, “although many school library media programs received funding in the consolidated laws, the consolidation of education programs ended the consistent growth of library media programs throughout the nation.” But in 2002, the US Congress decided to dedicate $250 million “funding for school library materials to get its school libraries back on track” (Haycock, 2003: 3).

In the UK, research on school library leadership focuses on a similar issue as in the US: the ability to create (or in some cases keep) an integrated library, a learning center for the school and the community. There are budget, collection, and staff issues. The strategic report by Streatfield et al. (2010) outlines these issues in school libraries in the present day UK. This report identified that many libraries did not have a policy in place (ibid.: 13), many libraries do not operate a full school day (ibid.: 31), the library stock does not grow proportionately to the growth in student numbers, and almost 30 per cent of school libraries have “fewer than 10 [computer] machines available for students in the library” (ibid.: 35). The report also highlights the importance of a reporting structure for libraries in schools: “who the librarian reports to can be viewed as an indicator of how the school views its library. 405 of the respondents (38.8 per cent) report to the Head or Deputy Head … but 105 (10 per cent) report to the Bursar, Finance Director or Business Manager, which is likely to weaken the librarian’s scope for engaging with curriculum matters.”

In Australia, too, school libraries have struggled for survival. There have been suggestions that they work with public libraries, not only to ensure survival, but to provide continuous learning, to provide access to more users, and to continue to be educational laboratories for all students. In spite of the many reports that shed light on the limitations of school and children’s library services in Australia since 1964, the trend continues (Bundy, 2002). The National Institute of Quality Teaching and School Leadership in Australia was established in 2004 to raise the status, quality, and professionalism of teachers and school leaders throughout Australia. The Australian School Library Association (ASLA) and the Australian Library and Information Association (ALIA) together formed a partnership to address common priorities in schools and libraries. This included “articulating and promoting the role of library and information services and staff within the school community” (Mitchell, 2006: 42). Bundy’s suggestion is joint-use libraries, where public and school libraries cooperate in a formal way to fill the gaps in services and collections, and to provide a continuum for a student researcher/learner from school to public library to college or academic library as they progress into adulthood. The 2003 article published by Demos also suggests that different kinds of libraries and museums have commonalities. The article goes on to say that “there are great areas of overlap where the domains can come together to improve their performance” (ibid.: 18). Joint-venture libraries exist in Canada too and the most common of these is the school/public library (Wilson, 2008).

In 2003, Haycock released an executive summary of the state of school libraries in Canada, in which he stated that US researchers found a direct correlation between test scores or better performance at university or college levels and having a full-time teacher librarian in US schools. Haycock observed that no such study had been carried out in Canada and spoke of the decline in the state of the school library when he said, “only 10 per cent of Ontario elementary schools have a full-time teacher-librarian, compared with 42 per cent twenty-five years ago …” (ibid.: 6). Other provinces didn’t fare well either. In 2011, he confirmed that wellstocked, well-staffed school libraries do make a difference to student learners by creating an interest in reading and providing high-quality learning. School library leadership literature focuses on niche leadership issues. This is perhaps due to the constant threat to budgets and staffing. The ESEA mentions leadership in school libraries only in relation to “selecting, acquiring, organizing, and using instructional materials” (Michie and Holton, 2005: 4). Academic and public libraries focus on these niche leadership issues as well, but with both of them, especially the academic libraries, there is a need for someone to lead the organization as a whole and, therefore, the leadership research focuses on the leaders’ experience, expertise, and overall efficiency.

In school library leadership literature, there are papers on being visionary leaders, literacy leaders, or transformational leaders to be prepared for the “worst of times.” And these papers focus on being able to build or keep a collection with creative problem solving by being visionaries, and transformational leaders. Smith (2010) focuses on transformational leadership in school libraries and her focus is on the one most important skill librarians would require to become efficient transformational leaders – technology. Although Smith’s paper focuses only on 30 pre-service school library media specialists from six Florida counties and the impact of their technology training on transformational technology, it is clear that a lack of current technology and/or a lack of knowledge of current technology is an issue in many school libraries. Oberg (2010) refers to technology as a “daunting challenge” for school librarians. She quotes other authors who challenge librarians to understand and respect the world of video-gamers and their ways of learning. Dow (2010) speaks of transformational and transactional leadership as necessary for school librarians who are (or should be) information and technology literacy leaders. Coatney (2011) writes of being prepared for leadership during hard times when there is no budget for new acquisitions; maintaining collections and staffing for school libraries and library programs through “creativity, compassion, and collaboration to reach the ultimate goals” (ibid.: 38). A similar vein runs through Johns’ (2011) article in which she refers to the 4 Cs of leadership as “ Communication, Collaboration, Critical thinking and problem solving, and Creativity and Innovation,” in that order. Achterman (2010) focuses on how to be a literacy leader by “gain[ing] a deep understanding of the reading and writing processes, of the best practices for teaching literacy skills across the curriculum, of the role technology plays in literacy instruction and learning, and of best practices in the ways school librarians contribute to student literacy gains.” School librarians need to be proactive in their leadership roles by approaching teachers and administrators with new ideas for incorporating research skills into the school curriculum. They need to be proactive in teaching administrators and teachers that their library is more than a warehouse for books.

Apart from the challenges of funding and issues related to it, school librarians, in spite of being in a teaching environment, also do not have an evaluative function. Academic librarians teach classes on using library resources and there is therefore an evaluative aspect to their role. Many academic librarians are expected to publish and this makes them researchers and self-evaluators. But in most school libraries library usage is not part of the curriculum, and while students are encouraged to use the library, they are not evaluated on their knowledge of the intricacies of catalog searches or the difference between using a database and Google for searches. Mitchell (2006) highlights a significant debate caused by the inclusion of the phrase “evaluate student learning” in the Standards of Professional Excellence for Teacher Librarians in 2005. Many teacher librarians did not see this as their role. Since school libraries form the foundation for learning, having a well-established school library where student users are not only taught but also evaluated for their active library learning will create an enlightened student population when they move to universities and colleges. Coatney (2011) sees this as an opportunity to establish leadership in school libraries. She speaks of leadership in terms of collaboration: constantly learning, relying on others, working hard to honor all learners, and determining what is best for a student as a learner (ibid.: 40). A school librarian has to be proactive in taking on or creating new projects that will establish the library and its resources, along with the librarian’s services, at the center of the curriculum. Without proper leadership, school libraries become models of servitude rather than places of learning.

Lack of applications from school librarians

Jones (2011) quotes Peter Bromberg, one of the program facilitators of the Emerging Leaders Program, on selecting applicants for the program as saying, “we do not want an overwhelming percentage of emerging leaders to be academic librarians for example and sacrifice special librarians and school media librarians.” Whether this implies that there are so many academic librarians applying for the program that school media librarians do not get a chance at this leadership program is not clear. But the shortage of school librarians in a position to apply for the program is a concern. The ALA page on Emerging Leader Participants for 2011 does not specify whether the participants are from school, public, or academic libraries, but judging from the sponsors there are five school librarians in the program. The lack of interest from school librarians for participation in a leadership program, or their inability to commit six months, or any length of time, to a leadership program during their working year is a challenge. Even a program set within a virtual learning environment is a challenge as many school librarians are solo librarians or the only personnel in their library. Winston and Neely (2001), in their research on the Snowbird Leadership program, identified that most of the applicants were either from public libraries (44 per cent) or academic libraries (16.66 per cent).

In a school library situation, the principal’s support in establishing and maintaining a good library is of the utmost importance. If the leadership at the principal’s level is not receptive to innovative ideas for the school library (or even for keeping the school library), then there is a problem. Supporting a library includes hiring librarians rather than having existing teachers take on the librarian’s role, providing technology support for librarians, including library research as part of the curriculum (this may have to be worked out with the school board), improving technology, and keeping up with technology trends. Libraries should not be seen as warehouses for information keeping, but places of reading, learning, sharing, and distributing information. It doesn’t help when fewer than 7 per cent of principals in Arizona believe that “school library media specialists should exercise leadership roles in the educational community” (Hartzell, 2002: 93). So in cases where principals are not aware of the library’s importance, existing teacher librarians should take on the leadership role in enlightening principals and the school community. Having said that, it is also encouraging to know that in the last two decades or so researchers in education have begun challenging the “pervasive view that equates school leadership with principalship” (Foster, 2005: 35). Saunders’ (2011) article highlights the importance of leadership through instruction and states, “teacher leaders understand the political landscape of the institution and organizations within which they function, know where the power bases lay and understand how to act strategically within this framework” (ibid.: 268). Teachers can be leaders.

While there is some literature on leadership in school libraries, there is a lack of literature on ethnic-minority leadership in school libraries in the UK, the US, Canada, and Australia.

Public libraries and leadership

Public libraries have established leadership in many areas in the past – information literacy, joint-use libraries, interdisciplinary collections (something for everyone), computer literacy, free computers for public use, multicultural collections, multilingual collections, special services for homebound seniors, etc. – but research shows that many public libraries, at least in the US and Canada, are unprepared when it comes to future leadership. Public libraries owe their birth and existence to many like William Ewart, Andrew Carnegie, and Melvil Dewey for the roles they played in creating and establishing public libraries, and to all the supporters of knowledge who created a structure and a place for libraries and considered knowledge to be a public property to be available free of charge. William Ewart sponsored the Public Libraries Act of 1850, fighting the Conservatives to do so, and finally managed to pass a bill after many modifications that portrayed public libraries as having a reformative role rather than an educational role. Ewart and supporters of this bill saw public libraries “as a counter-agent to evils rather than as a positive force for educational or recreational benefit” (Max, 1984: 504), and Ewart firmly believed in education as the “great preventative measure” against crime (ibid.: 507). Later public libraries were seen as places of knowledge, where information was available for free. They also began to evolve as social spaces, with programs for children, young adults and adults, and multicultural groups. In spite of a library’s usefulness and immediate relevance to the community, every once in a while there is an economic crisis that threatens its existence. In the UK, “The Public Libraries Act 1964 still provides the national statutory framework and the general context for local service delivery by local authorities, who are the accountable bodies” (Daines, 2009). At the time of writing this chapter, one of the biggest issues being discussed among UK librarians on the public library list serve via CILIP was the announcement by the Mayor of Newham, Sir Robin Wales, to remove all multilingual newspapers from libraries so as to encourage immigrants to learn English. With over 150 languages spoken by the residents of this London borough who use its library, this is, to say the least, the worst leadership move a Mayor can make (BBC, May 10, 2011). It takes the library and its users a few steps backward. One of the ways to integrate new immigrants into a society is by providing information in a language they understand and are most comfortable with. This will help with the social inclusion of new immigrants. Without information new immigrants cannot integrate into their new societies, and this will cause a major disturbance in the social fabric of multicultural societies such as England. The difference between informational “haves” and “have-nots” creates a major disparity among citizens of a society and this contributes to differences in their economic and educational possibilities, which does not contribute towards a knowledgable, selfsustaining society. As Caidi and Allard explain:

To stifle individual expression or attempt to subsume it under a repressive notion of social cohesion may be what leads to the disruption of the social fabric. An imposed homogeneity for the sake of a false notion of sameness may in fact be what encourages social alienation, isolation, and exclusion.

(Caidi and Allard, 2005: 311)

In Canada, lending institutions have existed for more than 200 years and each province and territory has its own library act and a system that mandates its funding, partnerships (Wilson, 2008), and therefore its staffing and collections. Public library history in Australia was established after the Library Bill was passed in 1939. Prior to that, libraries existed as subscription reading rooms. The Munn-Pitt Report of 1935 stated that Australian libraries were “wretched little institutes” and “cemeteries of old and forgotten books.” These libraries were run by untrained staff, with limited public access. The release of this report was the catalyst for the establishment of Free Libraries, as they exist in Australia today. They were established as government-funded services and continue to be so today (Berryman, 2004). There are over 1,500 public libraries in Australia, although not all of them have all the necessary facilities or services, for a number of reasons such as the lack of a network for internet access. This resulted in the establishment of Public Libraries Australia (PLA) in 2002, before which there was no national body to represent the Australian public libraries. Since then the PLA has served as the voice of the public libraries at the national level by providing advocacy and support, by lobbying the government for funding in Australia, and by being the single point of contact for the Federal Government on matters of online accessibility (Makin and Knight, 2006). Bundy (1999) wants librarians to go back to the idea that libraries are about reading, not information retrieval. Of all three library sectors, this thinking can be best applied to public libraries where users come to read for pleasure or to gain knowledge. Bundy’s tone indicates that librarians (and library users) are now techno-lusts and that they should return to promoting reading as the catalyst for public libraries to thrive. He argues that public libraries are used by 11.4 million Australians, comparing this to the 30,000 or so students at a university setting in Melbourne or Sydney. Perhaps it is the lack of perspective that public library leadership needs to focus on.

In the current economic climate, public libraries, too, are struggling to stay open, in the same way as are school libraries. Libraries have become the first target when funding is an issue, and smaller libraries in many communities in the US have had to close their doors. The closure of public libraries is also a major concern in the UK (McMenemy, 2009). In England and Wales, 179 service points were closed between 1986–1997 due to financial, structural, contractual, and low-usage reasons (Proctor and Simmons, 2000). Davies (2008) observes that the Conservative Government singlehandedly caused a decline in library usage through insufficient funding, lack of partnerships, lack of training, and the deskilling of libraries by hiring lay staff and volunteers instead of librarians. He blames this Government for the actions that pushed the “library service into the orbit of private sector and changed irrevocably the character of the service” (ibid.: 4). Stewart (2011) reports that 375 public libraries across the UK could soon face closure.

During a recession, there is an inflation of prices on books and other information packages and public libraries are often unable to add to their collections. Jobs may also be cut and, due to shortages in personnel, maintaining collections and offering other services becomes a challenge. Ironically, the same reason, an economic crunch, can also be a reason for an increased usage of library materials. Rooney-Brown (2009) provides evidence of a connection between an increase in the usage in libraries across the US and the economic downturn in his article, and confirms that there is a “growing body of statistical and anecdotal evidence which supports the theory that there is indeed a link between public library usage and economic crises” (ibid.: 342). Davies (2008) confirms this by stating that in 2006–2007 more people in the UK visited libraries than either football matches or the cinema.

Leadership literature on public libraries shows the lack of preparation on the part of public libraries when it comes to succession planning. As Mullins and Linehan (2005) found, many public librarians in Ireland and Britain stated that “library chiefs do not have a mental picture of themselves as real managers or leaders” and that they are “books people, not leaders,” but all agreed that libraries need effective leadership (ibid.: 392). Many public libraries also do not have strategies in place for finding the right leadership for the future of their library. Succession planning should not be about finding a replacement when a person retires. It should be about mentoring all existing librarians and identifying the right person for the right leadership positions that may come along at any given time. Librarians who are identified as potential leaders should be involved in succession planning. This will provide motivation and help with retention. As Whitmell (2011) explains, individuals should not be identified for specific positions or advancement without discussion with the individuals involved to be sure that they want the job and are willing to undertake the needed training and coaching to get there. The plan must be flexible and adaptable to change. Individuals identified for leadership positions should be from different cultural backgrounds.

What are public libraries doing about ethnic-minority leadership?

In the UK, CILIP published its Encompass Toolkit (2009) offering guidance and advice to library and information organizations to undertake positive action training initiatives. This report highlights the importance of cultural diversity among library employees and offers ideas on how to conduct training programs, what supervisors and trainers need to be aware of during training, and the dos and don’ts of such a program. This training program is meant to offer wellrounded career development advice about the library field without making assumptions about the trainee’s choices. In Canada, the Canadian Library Association (CLA) speaks only of the provision of multicultural services and collections to users and nothing of hiring minority librarians in the various sectors. The CLA’s position statement explains, “The Canadian Library Association believes that a diverse and pluralistic society is central to our country’s identity. Libraries have a responsibility to contribute to a culture that recognizes diversity and fosters social inclusion.” The Public Library Association (PLA) of the US, a division of the ALA, also has nothing on hiring public librarians at their libraries, but refers to the ALA for its diversity issues, which covers topics such as combating racism, library education to meet the needs of a diverse society, the recruitment and retention of diverse personnel, and leadership development and advancement for diverse librarians. At the time of researching for this book, there was nothing to be found within the Public Libraries Australia (PLA) or the Australian Library and Information Association (ALIA) regarding hiring and retaining diverse librarians, and the author’s emails to the PLA on the matter went unanswered.

Leadership programs for public librarians

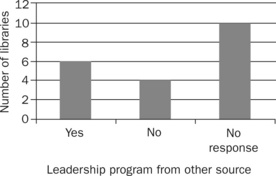

Most public libraries do not offer their own leadership programs and often rely on other sources in their community or library organizations for such programs. Some of the community programs may not be tailored for librarians and this could pose a challenge. In some cases, librarians may have to travel to different places to complete their leadership workshops and this is not always a feasible option for many. It is left up to the librarians in these programs to learn, synthesize, and apply their newly acquired leadership knowledge to their own work environments. The benefit of what is learnt in these programs will wear off if not practiced within a supportive environment within the library, and this is another challenge for public librarians. Having the time to practice learnt leadership skills in a supportive environment is a luxury that most public librarians cannot afford due to a lack of staffing and funding, etc. Since leadership programs cost money, librarians at public libraries mostly go to one or two short-term leadership programs and this alone is not a good learning opportunity. Public librarians should also remember that leadership is not just about attending leadership workshops or becoming members of various library associations, but applying what is learnt at these workshops and using the skills learnt from being members of library associations in their work environment. Public libraries need to create a supportive environment for those identified as potential candidates for leadership. And these candidates should be chosen from diverse backgrounds and cultures with diverse knowledge to truly represent the community they serve.

Public librarians have relied on peer-mentorship to learn their jobs and develop leadership skills. Gail Doherty (2006) warns that while this is commendable it can also lead to clashes of style: younger librarians are more comfortable with technology and may have different communication styles and approaches to objectives. Older librarians may be reluctant to use technology and may have a different perspective on their work. But leadership learning and practice involves going beyond one’s comfort zones and learning to work with various styles and skill sets in different people.

How can leadership help public librarians?

It is encouraging to know that libraries are well used, especially so during a recession, and public library leaders need to focus on leadership to acquire funding to maintain their library. Since libraries enhance the lives of ordinary people and create informed citizens, this is an important task for public library leaders to consider. Mullins and Linehan (2005) highlight the need for political skills among library leaders, an important skill since libraries rely on the support of politicians for resources. They say, “political skills and political correctness are also needed to deal successfully with management and especially senior management” (ibid.: 137). In the absence of a school library, a public library is one of the few places young users can go to get free information. Finding and forming partnerships, using fiscal and technology skills to provide as many services and programs as possible, using communication skills to let government bodies know how valuable the library is for a community, making the library a hub of the community by working with various groups, schools and even local colleges and universities, all require creative leadership. Finding funding is not an easy task for public libraries anywhere, but finding those funds and using them wisely makes one a good leader. Good leadership will create libraries that can flow with change, manage change, and accommodate new ideas in order to maintain successful libraries of the future. Good leadership should be about finding ways to take libraries beyond their fight for survival with every economic downturn.

Leadership in academic libraries

Similar to school libraries, but unlike public libraries, academic libraries speak of leadership in terms of instruction. As discussed previously, school librarians do not have an evaluative role in their instruction but academic librarians do. Hence, instruction is seen as an integral part of the academic librarian’s job. Providing good instruction means that librarians constantly work on developing their professional skills through continuing education, research, workshops, and training. Leadership in academic libraries can be established in technology, research skills, mobile resources, etc. With so many disciplines on campus in any given academic library, leadership for librarians and library staff can expand across disciplines. As public and school libraries speak of joint-use libraries, academic libraries speak of an interdisciplinary approach and this is another area where leadership can be established. The buzzwords related to this concept are “community,” “stakeholder,” “public-relations,” and “internal-marketing” (Bussy and Ewing, 1997).

Much of the literature available on ethnic-minority librarians is from academic libraries and this can be found sprinkled throughout this book. There could be various factors that contribute to this, one of them being the expectation on academic librarians to publish or perish. Weiner (2003) highlights some leadership-related topics and cites papers that focus on these topics. Under diversity issues, she refers to papers that focus on women as leaders but has nothing to report on ethnic-minority librarians. Winston (2001) has written many articles that focus on minority librarians in an academic setting and in his article entitled “The Importance of Leadership Diversity: The Relationship between Diversity and Organizational Success in the Academic Environment” he observes that “fostering diversity within organizations goes beyond the fact that it is a good thing to do.” Though there is no known direct relationship between diversity and organizational success, organizations that are diverse and successful have managed to be successful by drawing “a wide pool of talent up through their ranks and is [are] opening itself [themselves] to a variety of different views and ideas” (Kuczynski, 1999). In a library situation, a diverse group of librarians will help serve the demographics represented and will help target multicultural users of libraries and promote multicultural collections. But these are not the only reasons libraries should be diverse. Switzer (2008) asks that we stop paying lip-service to the idea of tolerance and commit ourselves to multiculturalism and ethnic diversity. She speaks of academic campuses altering their mission statements to reflect their commitment. She, too, offers a literature review of the subject from 1987.

Leadership programs for ethnic-minority librarians in the US, Canada, the UK and Australia

There are a number of leadership programs available in the US, Canada, the UK and Australia, for all librarians and library staff to attend, but few focus on ethnic-minority librarians.

United States

Association of Research Libraries (ARL) – its Leadership and Career Development Program is an 18-month program that helps mid-career level librarians from diverse groups work towards their leadership roles.

Minnesota Institute – This program is offered once every two years and focuses on ethnic-minority librarians who have been in the profession for less than three years. It has two components: technology training and leadership. This program admits Canadians as well. The director or dean of the participant’s library has to recommend the participant for the program.

Spectrum Scholarship – While this is not a leadership workshop, this scholarship encourages applicants from minority groups to apply to library schools. Established in 1997, Spectrum “is ALA’s national diversity and recruitment effort designed to address the specific issue of underrepresentation of critically needed ethnic librarians within the profession while serving as a model for ways to bring attention to larger diversity issues in the future” (ALA, 2011). (http://www.ala.org/Template.cfm?Section=scholarships&template=/ContentManagement/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=55694)

Canada

While there are many leadership programs available in Canada, such as The Northern Exposure to Leadership in Edmonton, The Emerging Leader Program in Calgary, and institution-based leadership programs for academic librarians, there are none that focus on minority librarians.

Australia’s Aurora Leadership Program

The Aurora Foundation aims to “develop leadership capacity in the library and information professions in Australia and New Zealand by developing and providing innovative and challenging programs” (Aurora Foundation Limited, 2011, http://www.aurorafoundation.org.au/). The Foundation offers two different classes through the Aurora Institute: Emerging Leaders and the Masterclass in Strategy in Innovation. Emerging Leaders is for those who have been identified as potential leaders by their organization and have two years’ experience in a supervisory role. This program is not only for librarians, but also for employees from museums, archives, records management, galleries, etc.

United Kingdom

There are no leadership programs to be found for librarians or ethnic-minority librarians. The only program mentioned on CILIP is the Encompass Toolkit mentioned earlier.

Leadership programs have identified some important factors to help foster leadership in minority librarians. One major factor is networking. At the Minnesota Institute, participants created a listserv and kept in touch about their professional lives. Being part of a network creates more awareness about possibilities in the profession and this awareness is one step towards leadership. Another factor is using inventories to identify the styles and personalities of participants. This helps minorities learn about their current styles and preferences, and when they know where they stand it is easier to identify where they want to go and how to get there. Learning to build new skills is also a factor. Some of the leadership programs have a skills component where the latest multimedia skills are taught. For first generation ethnic-minority librarians coming from various backgrounds this would be a beneficial component in a leadership program.

Statistically speaking

Three different survey questionnaires (see Appendices A to C) were administered electronically to ethnic-minority librarians, deans and directors of libraries, and directors of library schools in the UK, the US, Canada, and Australia. As a result of how the survey was administered (more publicizing points within Canada but a lack of information available from ALILA and CILIP at the time), the results are likely to be skewed. But the purpose of the survey was to take the pulse of what is happening with ethnic-minority librarian leadership issues and is not meant to be exact science. The small sample size available in this study may raise concerns about arriving at conclusions on the immigrant population in leadership fields. The limitations were caused by a lack of responses from library school deans and the lack of availability of information regarding visible minority librarians in each country. While the US has many minority librarian groups such as the Asian Pacific American Librarian Association (APALA), the Black Caucus of the American Library Association, the Chinese American Librarians Association, etc., other countries did not always have such groups to where the survey could be sent (or they couldn’t be found). Particularly with Australia, the distribution of the survey mostly depended on ALIA.

The survey ran from (approximately) March 7, 2011 to April 22, 2011 (depending on when it was posted by the library associations). Forty-five ethnic-minority librarians, 20 deans and directors of libraries, and eight library school directors from the UK, the US, Canada, and Australia responded.

Ethnic-minority librarians survey

For Australia, the survey was sent to ALIA for distribution. As there weren’t enough responses, individual library email addresses for as many libraries as available (academic, school, college, etc.) were culled from the internet and surveys sent.

For the UK, the best hope was CILIP. When emails reached librarians, one or two of them suggested other email lists (e.g., the Diversity Group e-list) to which to send surveys and surveys were sent to these email addresses as well. As with the Australian libraries, individual library emails to as many libraries as were available via Google were used to send surveys.

For Canada, the survey was sent to the CLA, who distributed to all its members. Survey information was also sent to individual provincial associations.

In the US, the survey was sent to the ALA and all other associations in the US, as listed on the ALA site (e.g., APALA).

Fifty-five per cent of librarians from the US, 35 per cent from Canada, 6 per cent from the UK, and 2 per cent from Australia responded to the survey. Of these, 13 per cent of librarians said their education was from their home country and was therefore not valid. They had to do other courses and build their skills before securing any library positions. The remainder had acquired their library degrees from their new home country.

With regard to the leadership questions (see Appendix A, questions 29 and 30), 40 per cent of the librarians were sure that they were in leadership positions due to the nature of their job. Sixteen per cent of them thought that they were “kind of,” “sort of” leaders due to their positions. Thirty-eight per cent were sure that they were not leaders.

With regard to the questions on leaders (see Appendix A, questions 33 and 34), these were the reponses: leaders have a vision, are people oriented, lead by example, lead during change, make decisions based on feedback from others, have knowledge of their work, motivate others, have ideas, initiate ideas, and go beyond what is expected of them. In addition:

![]() Leaders set direction and pace; managers assign work and schedule time.

Leaders set direction and pace; managers assign work and schedule time.

![]() Leaders motivate; managers expect the job to be done.

Leaders motivate; managers expect the job to be done.

![]() Leaders set goals; managers make sure they are accomplished.

Leaders set goals; managers make sure they are accomplished.

![]() Leaders determine policy; managers administer such policies.

Leaders determine policy; managers administer such policies.

![]() Leaders can be found at all levels of an organization.

Leaders can be found at all levels of an organization.

![]() Leaders are good managers as well, but unfortunately not all managers are leaders.

Leaders are good managers as well, but unfortunately not all managers are leaders.

With regard to the last question on whether their organization would support them in their leadership aspirations, 62 per cent of the librarians answered “yes.” The remainder were not sure and cited budget issues, time constraints in attending workshops, and a lack of opportunities in their current workplace.

Survey for deans and directors of libraries

A link to this survey was sent to the Dean and Associate Dean of the University of Saskatchewan to be distributed to COPPUL (Council of Prairie and Pacific University Libraries) and ACRL members in Canada and the US.

For Australia and the UK, ALIA and CILIP were asked to distribute the survey to all relevant groups. Ten per cent of the responses were from the UK and 5 per cent were from Australia. The remainder (85 per cent) were from Canadian universities. Ten per cent of the responses were from deans of public libraries and 90 per cent were from academic libraries.

When asked about the number of visible minority librarians in their libraries, the average ranged from 4 per cent to 9 per cent. Only one university (in Canada) had 16 per cent visible minority librarians.

When asked about a leadership crisis in their libraries, 25 per cent of the respondents answered with an emphatic “yes.” They believed there was a leadership crisis.

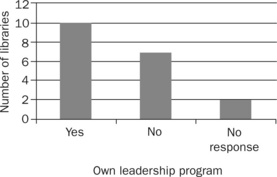

Forty-five per cent of all the libraries had their own leadership program that was offered through their Human Resources department, or workshops on management issues, along with staff mentoring and buddy systems. None of them mentioned a program tailored for their own librarians.

Forty-five per cent of deans and directors of libraries in the UK, the US, Canada and Australia recognize non-North American library degrees with some stipulations: either a committee had to approve hiring a non-North American degree holder or the degree had to meet ALA standards.

Fifty-five per cent of the respondents replied that they did not have plans to offer cross-cultural leadership programs, 10 per cent were not sure, and the rest did not respond to this question.

Survey for deans and directors of library schools

In Canada and the US, a link was sent to the library schools with contact information on the internet. For Australia and the UK, ALIA and CILIP were asked to distribute the survey to all relevant groups. Unfortunately, there were only 8 respondents (1 from the UK and 7 from the US). Due to the low number of responses, this is not the perfect sample for evidence of what is happening in library schools.

Of those who responded, 5 (62.5 per cent) mentioned leadership as a core course in their library programs. Only 25 per cent have an ethnic-minority focus in their leadership program while others have modules that focus on intercultural communications and mentoring programs for ethnic-minority students that provide leadership support.

As mentioned above, due to the low number of responses, the survey does not give a true indication of what is happening in libraries and library schools in the UK, Canada, the US, and Australia. Librarians in these countries should focus on creating survey questionnaires for their own libraries and library schools to provide a true indication of what is happening with the ethnic minorities in their library communities. As for Canada and Australia, library associations for various minority groups need to be formed. The national library associations in these countries can provide guidance and support to create such ethnic-minority focused library associations that can do more work in the library community to seek, encourage, and train other ethnic minorities from their own ethnic groups to join the library world. All library schools must introduce a leadership course with modules on intercultural leadership issues as a core component of the course. There should also be a module that explains the difference between management and leadership.

Introducing ethnic minorities into libraries and encouraging them to be leaders alongside their local cohorts is not an impractical task. By taking baby steps to create minority library associations that will help in recruiting more students into library schools, by creating a leadership course that integrates the leadership ideas of all cultures, by introducing librarians to different communication styles from different cultures, by making leadership a mandatory course in library schools, by offering intercultural leadership workshops and time for librarians to practice it in their workplace, this aim can definitely be achieved.

References

Achterman, Doug. 21st-Century Literacy Leadership. School Library Monthly. 2010; 26(10):31–43.

Acree, Eric Kofi, Epps, Sharon K., Gilmore, Yolanda, Henriques, Charmaine. Using Professional Development as a Retention Tool for Underrepresented Academic Librarians. Journal of Library Administration. 2001; 33(1):45–61.

All-Party, All-Party Parliamentary Group on Libraries Report of the Inquiry into the Governance and Leadership of the Public Library Service in England. Literacy and Information Management. 2011. [September 2009. Web. April 13].

American, American Library Association New Vision. Spectrum – New Voices. 2011. [Web. April 28, 2011].

Aurora, Aurora Foundation Limited Web. April 16, 2011. The Aurora Foundation. 2011.

BBC, Newham’s Libraries Remove Foreign Language Newspapers May 10, 2011. 2011. [Web. May 25].

Berryman, Jennifer, E-Government: Issues and Implications for Public Libraries 53.4. The Australian Library Journal. 2004. [Online].

Black, Graham, The Next Generation of Leaders: Leadership Development Programs for Australian University Library and IT Staff 453–462. EDUCAUSE. 2003.

Bundy, Alan. Promoting Reading to Adults in UK Public Libraries. Australian Academic and Research Libraries. 1999; 30(1):65.

Bundy, Alan. Essential Connections: School and Public Libraries for Lifelong Learning. The Australian Library Journal. 2002; 51(1):47–70.

Caidi, Nadia, Allard, Danielle. Social Inclusion of Newcomers to Canada: An Information Problem? Library and Information Science Research. 2005; 27(3):302–324.

Canadian, Canadian Library Association Web. April 17, 2011. Position Statement on Diversity and Inclusion. 2008.

CILIP, All-Party Parliamentary Group on LibrariesLiteracy and Information Management. Report of the Inquiry into the Governance and Leadership of the Public Library Service in England, 2009. [Web. April 18, 2011].

Coatney, Sharon. The Blind Side of Leadership or Seeing it All. School Library Monthly. 2010; 27(2):38–40.

Coatney, Sharon. Leadership for Hard Times. School Library Monthly. 2011; 27(6):38–39.

Davies, Steve. Taking Stock: The Future of our Public Library Service. London: Unison Communications Unit; September 2008. [Web. January 12, 2011].

de Bussy, Nigel, Ewing, Michael. The Stakeholder Concept and Public Relations: Tracking the Parallel Evolution of Two Literatures. Journal of Communication Management. 1997; 2(3):222–229.

Demos, Towards a Strategy for Workforce Development: Research and Discussion Report Prepared for Resource March 2003. 2011. [Web. April 15].

Dhanjal, Catherine. How Technology, Leadership, Commitment and Soft Link Help Turn Schools Around. Multimedia Information and Technology. 2005; 31(2):38–39.

Doherty, Gail. Mentoring GenX for Leadership in the Public Library. Public Library Quarterly. 2006; 25(1–2):205–217.

Dow, Mirah J. School Library Leadership at the University Level. School Library Monthly. 2010; 27(2):36–38.

Foster, Rosemary. Leadership and Secondary School Improvement: Case Studies of Tensions and Possibilities. International Journal of Leadership in Education. 2005; 8(1):35–52.

Glegoff, Stuart. Information Technology in the Virtual Library. Journal of Library Administration. 2001; 32(3):61–84.

Hartzell, Gary. The Principal’s Perceptions of School Libraries and Teacher-Librarians. School Libraries Worldwide. 2002; 8(1):92–110.

Haycock, Ken, The Crisis in Canada’s School LibrariesThe Case for Reform and Re-Investment. Toronto, Canada: Association of Canadian Publishers, 2003. [Web. April 15, 2011].

Haycock, Ken. Connecting British Columbia (Canada) School Libraries and Student Achievement: A Comparison of Higher and Lower Performing Schools with Similar Overall Funding. School Libraries Worldwide. 2011; 17(1):37–50.

Hopkins, Dianne M., Butler, Rebecca P. The Federal Roles in Support of School Library Media Centers. Chicago: American Library Association; 1991. [Print].

Howland, Joan. Beyond Recruitment: Retention and Promotion Strategies to Ensure Diversity and Success. Library Administration and Management. 1999; 1:4–13. [Winter].

Johns, Sara Kelly. School Librarians Taking the Leadership Challenge. School Library Monthly. 2011; 27(4):37–39.

Jones, Darcel. A Year in the Life of One Emerging Leader. New Library World. 2011; 112(3/4):171–177.

Kuczynski, Sherry, If Diversity, Then Higher the Profits? December. HR Magazine. 1999. [Online].

Makin, Lynne, Knight, Robert. Senate Inquiry into the Role of Libraries in the Online Environment: Submission from Public Libraries Australia. Australian Library Journal. 2006; 55(1):6–11.

Max, Stanley M. Tory Reaction to the Public Libraries Bill, 1850. The Journal of Library History. 1984; 19(4):504–524.

McMenemy, David. Public Library Closures in England: The Need to Act? Library Review. 2009; 58(8):557–560.

Michie, Joan, Holton, Barbara, Fifty Years of Supporting Children’s Learning: A History of Public School Libraries and Federal Legislation from 1953 to 2000. National Center for Education Statistics. 2005. [Web. April 20, 2011].

Mitchell, Pru. Australia’s Professional Excellence Policy: Empowering School Libraries. School Libraries WorldWide. 2006; 12(1):39–49.

Mullins, John, Linehan, Margaret. The Central Role of Leaders in Public Libraries. Library Management. 2005; 26(37):386–396.

Museums Libraries Archives Council, Towards a Strategy for Workforce Development. A Research and Discussion Report Prepared for Resource. 2003. [Web. April 15, 2011].

Oberg, Dianne. Issues for the Next Decade. School Libraries Worldwide. 2010; 16.2:i–iii.

Proctor, Richard, Simmons, Sylvia. Public Library Closures: The Management of Hard Decisions. Library Management. 2000; 21(1):25–34.

Riggs, Donald E. Academic Library Leadership: Observations and Questions. College and Research Libraries. 1998; 60(1):6–8.

Riggs, Donald E. The Crisis and Opportunities in Library Leadership. Journal of Library Administration. 2001; 32(3):5–17.

Rooney-Browne, Christine. Rising to the Challenge. Library Review. 2009; 58(5):341–352.

Saunders, Laura, Librarians as Teacher Leaders: Definitions ACRL. Challenges and Approaches. 2011. [Web. April 18, 2011].

Shaw, Lucy, Encompass Toolkit: Practical Guidance and Advice for Employers in the Library and Information Sector on Introducing Positive Action Schemes. CILIP. 2009. [Web. April 18, 2011].

Smith, Daniella. Making the Case for the Leadership Role of School Librarians in Technology Integration. Leadership Role for School Librarians. 2010; 28(4):617–631.

Stewart, Nicola, Hundreds of Public Libraries Across UK Threatened with Closure January 22. Wessex Scene. 2011. [Web. April 18, 2011].

Streatfield, David, Shaper, Sue, Rae-Scott, Simon, School Libraries in the UK: A Worthwhile Past, a Difficult Present – and a Transformed Future? Main Report of the UK National Survey. 2010. [Web. April 25, 2011].

Switzer, Anne T. Redefining Diversity: Creating an Inclusive Academic Library Through Diversity Initiatives. College and Undergraduate Libraries. 2008; 15(3):280–300.

Weiner, Sharon Gray. Leadership of Academic Libraries: A Literature Review. Education Libraries. 2003; 26(2):5–18.

Whitmell, Vicky. “Facing the Challenges of an Aging Population: Succession Planning Strategies for Libraries and Information Organization”. (N.d.): 1–21. Web. April 15, 2011.

Wilson, Virginia. Public Libraries in Canada: An Overview. Library Management. 2008; 29(6/7):556–570.

Winston, Mark D., The Importance of Leadership Diversity: The Relationship Between Diversity and Organizational Success in the Academic Environment. College and Research Libraries, November 2001:517–526.

Winston, Mark D., Neely, Teresa Y. Leadership Development and Public Libraries. Public Library Quarterly. 2001; 19(3):15–32.