Leadership styles

Abstract:

Leadership theories such as trait theory, behavioral theory, and contingency theory are well known. Each of these theories, developed at various times during the 20th century, focuses on various styles for leaders. While the Great Man theory believed in leaders being born as leaders, other theories implied that leaders need to focus on styles and skills that will turn them into true leaders.

Speaking in S. R. Ranganathan’s style:

![]() Every leader his or her style.

Every leader his or her style.

![]() Every leader his or her set of skills.

Every leader his or her set of skills.

![]() Every leader his or her organization.

Every leader his or her organization.

As already mentioned, leadership is about influencing, mobilizing, motivating, inspiring, and enabling everyone to achieve their fullest potential. Persuading and motivating an organization are not easy tasks to accomplish. To do this effectively, leaders are expected to learn and practice, or at least be aware of, different styles and skills that they can use in different situations.

A leader with no leadership style, or with an inflexible leadership style, will not be successful in helping anyone achieve their fullest potential, and as a result will not be successful in leading the organization. Depending on the organizational culture and the expectations from the kind of audience one is leading, a leader may adopt a style that is authoritative, autocratic, participative, democratic, or delegative.

What is leadership style?

Style is the way in which a leader acts. It is the way in which the leader behaves while motivating, influencing, and accomplishing. Style can either be physiological as in body language, voice, eye contact, and words used, or characteristic as in showing humility, or intellective as in being intelligent or an intellectual. Style can be tangible or intangible. The style that a leader uses will depend on the individual’s values, beliefs, cultural background, organizational background, and personal preferences. Just as it is difficult to offer one definition for leadership, so too is it difficult to define what styles a good leader should possess.

A leader’s style may also be in the eyes of the beholder. A leader may act in a certain way with good intentions, but the interpreter might interpret this behavior entirely differently from how it was intended. Hence the style of a leader is also dependent on the interpretation of the receiver. There are also situational factors to consider in a decision-making process. Depending on the situation, the leader’s style may be demanding or just encouraging and motivating. A leader’s own behavior, the situation, and the follower’s interpretation of both the leader’s behavior and the situation all contribute to the style of the leader.

But, if the situation and the follower are removed from the equation, a leader’s own style is shaped by his/her own emotions, learning, and experience, and of course the cultural background from which they come. Studies in leadership theories define different leadership styles as necessary and effective in order to be a good leader.

Theories of leadership

The Great Man

In the early 20th century, with leadership literature just emerging, it was believed that leaders were born not made. Many leaders in various fields came from cultured, educated, and rich families, hence that assumption. It was called the Great Man theory. Of course, they were almost all men. As organizations continued to grow and evolve as a result of industrialization and, later, technology, these great men became outnumbered (by the number of organizations that grew up) and outmoded. But this theory is making a comeback according to some leadership researchers. David Cawthone, in his article “Leadership: The Great Man Theory Revisited,” shows that this theory has not been completely abandoned. He states that there are innate differences between leaders and followers that make them who they are and proceeds to ask:

How [then] are we to explain what seems painfully obvious if we refuse to recognize the Great Man Theory as one of many legitimate and meaningful avenues to our understanding of this most elusive topic [of leadership]? In brief, we can’t, for unless we are willing to confront those basic philosophical issues that have challenged minds throughout history, we are doomed to wallow in the obscurity of meaningless observations – observations that describe yet do little to penetrate the mystery of leadership.

(Cawthone, 1996: 4)

Trait theory

With “great man” becoming an endangered species, the next theory evolved. The first few decades of the 20th century focused on trait theory: a theory that argued that leaders needed to have certain traits. Within this argument, trait theory “did not make assumptions about whether leadership traits were inherited or acquired” (Kirkpatrick and Locke, 1991) but implied that all leaders had some common traits. Some of the common traits identified in leaders were: self-confidence; honesty; humility; aggressiveness; intelligence; dominance; energy; height; and knowledge about the job (Griffin et al., 2010: 323). Kirkpatrick and Locke (1991) emphasize that traits matter. While these “traits [only] endow people with the potential for leadership,” not all those who possessed these traits could or wanted to be leaders. Since leaders would need more than just these traits to be successful, leadership scholars questioned the effectiveness of this theory. Also, as the list of acceptable traits for leadership continued to grow, and because not all successful leaders seem to possess the listed traits, this approach to leadership was abandoned.

Behavioral theory

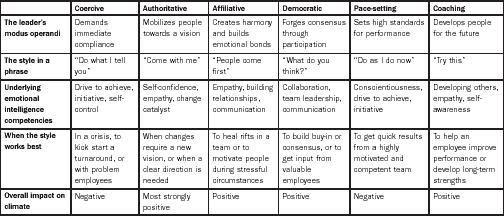

Another popular theory was the behavioral theory approach to leadership. This defined leaders not by characteristics but by their behaviors. Leaders or managers were either task-oriented or staff-oriented. Depending on their orientation, their leadership styles varied. Task-oriented leaders focused on achieving their tasks and might adopt an autocratic style. But staff-oriented managers were more worried about the job satisfaction of their employees. Leaders, according to behavioral theorists, were either coercive, authoritative, affiliative, democratic, pace-setting or coaching. As their names indicate, coercive leaders were more controlling and demanding, authoritative leaders led the way, affiliative leaders were empathetic, democratic leaders were participative, pace-setters were forceful in their leading style, and coaches were encouraging and motivating (see Table 3.1 on p. 82).

Situational theory and contingency theory

In the 1960s and 1970s two new kinds of leadership theory emerged. They were the situational theory and contingency theory approaches. While trait theory and behavioral theory focused primarily on the leader him/herself, situational theory focused on the situation (Antonakis et al., 2004: 152). Different situations require different styles of leadership. Different situations also create different kinds of leaders. What would Gandhi have become if India had not been under British rule? Would he have still become the great leader who is fondly known as the Father of the Nation? While situations create leaders, leaders don’t always have control of all situations at hand. A successful leader is also one who learns to adapt to different situations. Situational theory focused more on getting the task done than on developing people skills. One might argue that tasks cannot be accomplished without good people skills, but then one has to remember the autocratic leadership style that does get tasks done without focusing on developing human relationship skills.

Contingency theory states “that a leader’s effectiveness is contingent on how well the leader’s style matches a specific setting or situation” (Wolinksi, 2010). If leaders were successful in the roles they played, then it was considered a perfect match. Success in this theory was not determined by tasks accomplished, but by measuring the success of a leader’s relationships and their effectiveness in accomplishing success for the organization. This theory shifted the focus of the leader from being task-oriented to relationship-oriented (Antonakis et al., 2004: 155). Winston (2001: 519) quotes Dobbs, Gordon, Lee, and Stamps saying “that the aspect of leadership theory that relates most closely to leadership diversity is contingency theory, which is also called pragmatism, realism, and Realpolitik.”

Some more recent leadership theories are transformational leadership, transactional leadership, charismatic leadership, and virtual leadership.

While transformational leadership “refers to the set of abilities that allows a leader to recognize the need for change” (Griffin et al., 2010: 325), transactional leadership is about sustaining stability within the organization. Transformational leaders can work with change and some might even thrive in an environment of change, but transactional leaders are not always comfortable with changes in their environment and may not be the best leaders to manage change.

Charismatic leadership depends on the magnetic personality of the leader. While charisma can be an important trait for leaders, not all successful leaders have been charismatic. Winston Churchill was a great leader, but not many would have considered him to be charismatic. On the other hand, John F. Kennedy had charisma. A discussion of whether he was a great leader with strengths and weaknesses, or a charismatic leader, is beyond the scope of this book. The fear with charismatic leaders is that they could have unquestioning followers and this could mean the downfall of an organization, eventually. Having complete faith in any one person and letting them lead as they wish cannot possibly mean success in the long run. And the leader’s charisma may not necessarily help with his/her leadership qualities or abilities; it might just be their personality that is charismatic and therefore likeable. Then again, charismatic leaders have their place too: politics and the entertainment industry are great places for charismatic leaders. Being charismatic is an innate quality, not always a learnt one, and this is parallel to, if not similar to, Great Man theory.

Virtual leadership is still a fairly new kind of leadership. As the demographics of organizations change to include outsourcing and contracting various positions to hired workers in other countries, virtual leadership requires a new set of skills. It requires leaders to be able to work with people who are in different states, countries, and continents, in different time zones, from different cultures, and in different work situations. They may not have all the equipment needed, or a power shutdown on a given day might mean that work cannot be processed. Due to a political situation or a religious holiday in their own country, workers might not want to work on a particular day. A virtual leader has to be knowledgable not only about the work of the organization but also about the cultural work ethic of the different groups he/she has to work with, their political scenarios, and any legal issues with various demographics. This leader will depend a lot on email or phone communication where body language remains invisible to the listener. Apart from finding the right kind of leadership style, a virtual leader also needs to have great communication skills.

A leader should be aware of the organization’s policies and expectations, its administrative style, its employees and their expectations, its external environment, and its implications on the organization. The leader should be able to adapt his/her style to suit the organizational needs or choose an organization that requires his/her style of leadership. If there is a disconnect between the two styles, it can be disastrous. In January 1997, Elizabeth Martinez resigned from her position as Executive Director of the ALA. As Martin (1996) states, Martinez was “hailed as a strong and visionary leader who would be able to represent the profession effectively while managing this very complex and unruly organization,” but Ms. Martinez did not think the ALA was ready to change. There may be other underlying reasons for her resignation, but it came as a shock to the American libraries.

Styles that work

While an autocratic style worked in the industrial era and the post-Second World War era, when the economy was dependent on production from factories, and when managers were the boss and employees followed instructions, it is no longer the style of Western-world organizations, especially in libraries. There will always be managers or leaders in any organization who control, but it is not the norm, and ethnic-minority librarians should be aware of this. In many Asian, African, and Middle Eastern countries, leaders have the final say. In China, for example, historically speaking, leaders have had authoritarian leadership styles. Triandis (1993: 175) confirms this with the observation that a leader is “paternalistic, taking good care of his ingroup.” In many Asian and African cultures that are collectivist cultures, leaders are worshipped or feared to the point that they are not questioned. There is an emphasis on hierarchy. Authoritarianism is not the leadership style that is prevalent in the Anglo-Saxon culture of today, but there is no uniformity in style here either. The American leadership style encourages a collaborative effort from all employees in an organization regardless of their positions or titles, but in Australia, as Christina Gibson (1995: 274) states, “Australians indicated less emphasis on interaction facilitation and more emphasis on a directive style, which is more autocratic and benevolent.” In her article, in which she compares leadership qualities between four countries, Sweden, Norway, the US and Australia, Gibson believes individualism and masculinity to be more ingrained in Australians than in Americans, and traces this back to the history of ex-convicts having to be self-reliant in order to survive. This historical factor, along with geographical isolation, may have led Australians to prefer goal-oriented and directive leadership practices (ibid.: 273).

Today’s work culture is knowledge based, and leaders and managers are managing educated, intelligent, and, in many cases, experienced workers. Autocracy as a leadership style will affect the longevity of employees in an organization’s workforce. In the egalitarian work culture of libraries, leadership is a combination of styles and skills. Leaders are expected to be participative, authoritative yet democratic, to be able to balance tasks and people, and to be effective leaders in person and in a virtual environment, to be able to work with vendors, cataloguers, and publishers on a global scale, to work with librarians and staff from different cultures, and to be fiscally responsible. It is an overwhelming task that cannot be done without training and trial and error. As a minority librarian, it is necessary to know that while egalitarianism exists in the work culture, there is also a hierarchy within organizational roles. Not everyone can do everything without approval. Things have to be approved by higher authorities and/or other groups (committees) within organizations, and this culture is very prevalent in libraries.

So, as to which leadership style works is something the leader needs to work at and learn. Transformational leadership style has been hailed as the right kind of leadership style in the West in recent years (Jogulu and Wood, 2008). This is because, as mentioned previously, change is constant in today’s work environment, and transformational leaders are considered best suited to leading an organization through changes caused either by internal or external factors. Li (2001) quotes Robert House, Chair of Organizational Studies at the Wharton School of Management, University of Pennsylvania, as saying:

Organizational leaders in the twenty-first century will face a number of important changes that will impose substantial new role demands. These changes include greater demographic diversity of workforces, a faster pace of environmental and technological change, more frequent geopolitical shifts affecting borders and distribution of power among nation states, and increased international competition.

(Li, 2001: 175)

All of these have an impact on libraries and a transformational leader can enable smooth transformation in times of change. Transformational leaders can bring about this transformation, and Michael Fullan calls this “reculturing” (2001: 44). He goes on to say that leading in reculturing organizations does not mean adopting a chain of innovative ideas implemented one after the other, but “producing the capacity to seek, critically assess, and selectively incorporate new ideas and practises – all the time inside the organization as well as outside of it” (ibid.).

Weiner, too, confirms transformational style as a preferred style for libraries, and goes on to quote Suwannarat’s study which reveals that female directors (in libraries) exhibit higher levels of transformational leadership behaviors and therefore are more effective than male directors (Weiner, 2003: 14). But one style alone is never enough for one to be a successful leader. A good leader should be able to combine two or more leadership styles as the situation demands.

Kimberley (2010) discusses six styles of leadership and cites two of those as having a negative impact. Coercive and pace-setting styles of leadership are two styles that decrease employee engagement and therefore have a negative impact. The “Do what I tell you” and “Do as I do now” styles are top-down management styles and don’t take into consideration the different work styles of employees. On the other hand, four other leadership styles – authoritative, affiliative, democratic, and coaching – offer employees a chance to understand the organizational goals and therefore engage with them. Kimberley goes on to discuss the importance of the need for multiple leadership styles in today’s organizations and the ability of a leader to move seamlessly and naturally from style to style.

Factors in leadership style

There are many factors that contribute to the style of a leader. While cultural background (as in the culture that one knows and grew up in) and organizational culture are huge factors in what kind of leadership style one might develop, age and gender also contribute to leadership styles.

Age has been considered a factor in leadership style. Younger leaders are more energetic, proactive, tech-savvy, likely to experiment and to want to get things done. Experienced leaders are cautious, work more collaboratively, and are more in tune with the emotions of their subordinates. There is also research that suggests that a leader’s age may have an impact upon how active or passive their leadership style is. This does not mean that all young leaders are active and therefore trailblazers, nor that all experienced leaders are passive underachievers. In libraries, younger staff often complain that their senior management is not interested or is too slow in using the latest technology to improve library access, programs, and products. Does this lack of interest in technology have anything to do with the age of senior managers or leaders? Or are younger librarians too eager to use the latest technology available in their jobs?

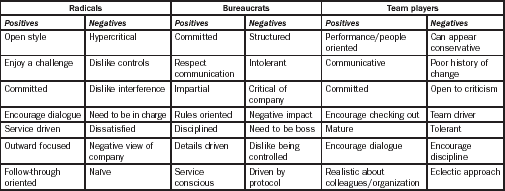

Considering the fact that many non-European-influenced countries respect their elders as leaders simply by virtue of their age and usually therefore experience, age could be a significant factor in how leaders act and think. A 25-year-old graduate, fresh out of university, may have great leadership skills, may have experience in leading students on campus, but may not have all the experience required to lead a big organization with its various dynamics and politics. While these younger employees are needed and appreciated for their fresh ideas and their readiness to take on challenges and for their technological skills, older employees are also needed and appreciated for their experience, knowledge, and skill sets. Both groups can bring their strengths to the success of the organization. In North America, leadership is not always necessarily restricted to older people. Kakabadse et al. (1998) refer to three leader profiles in their study of the Australian Commonwealth Federal Government – the radicals, the bureaucrats, and the team players – with the first group (radicals) being the youngest, between 25 to 35 years old, the second group (bureaucrats) between 46 to 55 years old, and the last group (team players) being 56 years and over. They noted that older workers were mature and had long-term perspectives, and younger employees were highly energetic, motivated, and competitive.

Table 3.2

Source: From Demographics and Leadership Philosophy: Exploring Gender Differences

In the debate with Vinnicombe (Vinnicombe and Kakabadse, 1999), Kakabadse concludes “that the more mature managers and leaders are, both in attitude and years, the better performer they become.” The best-case scenario would be for multigenerational librarians to bring their strengths together and work as one. Many committees in libraries try to recruit a diverse team, a team that is multigenerational, culturally diverse, with varied experiences, and from different demographics. Projects are more successful when people from different backgrounds come together with their own knowledge and skills. The worst-case scenario would be that the experienced leaders do not move forward to try to keep up with the younger generation of users that are using or need to use the libraries, and that the younger employees discount the knowledge and experience that experienced leaders have.

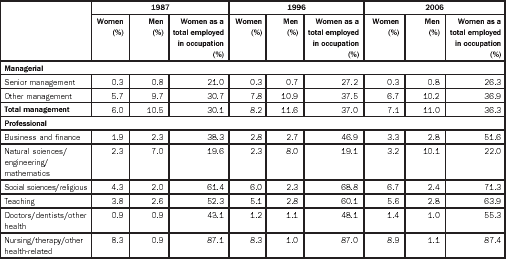

Does gender matter in leadership? Kakabadse in his debate (ibid.) also mentions that “gender is merely a red herring.” Many articles and books have been written on whether gender matters, and the answer is no, gender itself does not matter. Women, with their maternal instincts or just plain female instincts, come with their own strengths and weaknesses just as men do. In the 1990s, literature on women and leadership was about the glass ceiling that prevented them from moving into higher positions. But, in Canada at least, that has been changing, slowly but surely. Statistics Canada (2007) reported that more women were employed in 2006 than in 1976. It also reported that 7.1 per cent of women were in management positions in 2006, compared to 6 per cent in 1987, and that 32.5 per cent of women were in professional positions in 2006, compared to 24.1 per cent in 1987.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (2009) shows that more women have been employed since 1982. Equal Opportunity for Women in the Workplace Agency in Australia reported that as of February 2009, over 30 per cent of women were in managerial positions and 50 per cent of women were professionals (Australian Government, 2009). The United States Department of Labor (2009) also reported favorably on women and their jobs. As of 2009, more women were employed, and it is projected that more women will enter the workforce, to account for a 51.2 per cent increase in the workforce between 2008 and 2018. Women represent over 60 per cent of the workforce in managerial and professional occupations in the United States. But the UK’s National Statistics Online (2008) reported that greater numbers of men are employed than women, and that the ratio of men vs. women in the workforce hasn’t changed since 1999. The same report also stated that “men are ten times more likely than women to be employed in skilled trades (19 per cent compared with 2 per cent) and are also more likely to be managers and senior officials.” Inconsistencies exist in the ratio of men and women employed in different countries, and different provinces or states within these countries. Inconsistencies also prevail in different industries within these countries.

Table 3.3

Distribution of employment, by occupation, 1987, 1996 and 2006

1Includes occupations that are not classified.

Source: Statistics Canada, Women in Canada: Work Chapter Updates, 89F0133XIE2006000, Table 11, April 2007; http://www.statcan.gc.ca/bsolc/olc-cel/olc-cel?catno=89F0133XIE&lang=eng#formatdisp

Libraries, as an industry, have traditionally been dominated by women in many of the Anglo-Saxon countries. Libraries in North America, the UK, and Australia are female-dominated organizations. Melvil Dewey, the father of modern librarianship, the man who transformed librarianship from a vocation into a profession by creating a classification standard, by forming the first library school in Columbia and a formal association for librarians, was a pioneer in library education and created career opportunities for women in libraries. He may not have brought women into the library profession for all the right reasons, but, even today, libraries continue to be dominated more by women in these countries (OCLC, 2011). Dewey admitted women into his library school and later hired them as library professionals because they were cheap labor. In 1883, Dewey worked with his friend, Walter S. Biscoe, to reclassify and re-catalog the collections at Columbia College. In order to help Biscoe, Dewey decided to do things that would provide higher gains for lower costs. In his biography of Melvil Dewey, Wiegand (1996: 85) explains, “although he [Biscoe] did not say it, Dewey was, he believed, setting an example for the rest of librarianship; he was recruiting a work force with high character for low cost.” Dewey believed that college-educated women had the right “character” for library work and “because they were grateful for new professional opportunities, they would come for less money” (ibid.). Weigand goes on to say that “because by design the institution [library] served and supported the reading canons of a white middle-and upper-class patriarchy, Dewey found it easy to recruit women into the profession in order to fulfill cheaply and efficiently the supporting role he had assigned it” (ibid.: 372). Dewey believed that these women would not be a threat to the dominant culture and that they would be his loyal soldiers.

Australia reports that females dominate the fields of the library and archives professions. As the Australian Bureau of Statistics (2009) states, “Cultural industries where females were noticeably predominant were Libraries and archives (76.2 per cent were females), Arts education (73.8 per cent) and Newspaper and book retailing (64.0 per cent).” The 8 Rs study entitled The Future of Human Resources in Canadian Libraries found that females dominated the library profession in Canada as well (8Rs Research Team, 2005). In their report that surveyed libraries and librarians all over Canada, the team found that “overall, females are significantly more represented than males, with nearly eight in ten librarians being female” (ibid.: 43). The team also found significant differences in female representation between managerial and non-managerial positions (see Table 3.4).

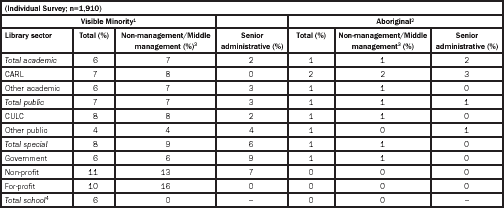

Table 3.4

Percentage of visible-minority and Aboriginal librarians by occupational level and by library sector

1Visible minorities include those who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour (e.g., black, Asian, Middle Eastern, Hispanic).

2Aboriginal individuals include those who identify themselves as Status Indian, Non-Status Indian, Métis or Inuit.

3Includes non-management, middle management and supervisors.

4Results are not presented for senior administrators working in school libraries because of insufficient cases reporting; however, they are included in the total sample results.

Source: 8Rs Canadian Library Human Resource Individual Survey

They also go on to say this about visible minorities in libraries:

Table 3.4 reveals that visible minorities are not well represented in Canadian libraries, comprising only 7% of the professional librarian labour force (compared to 14% in Canada’s entire labour force). The largest portion of visible minorities is found in non-profit and for-profit special libraries (11% and 10%, respectively), although this is still below the national average. Visible minorities are even less likely to be working as senior administrators and this is the case for all but the government sector.

The study also says “little hiring of immigrants is taking place within the library sector.”

One reason why women are under-represented in leadership styles could be, as Jogulu and Wood (2008) have found, that women experience disadvantages from prejudicial evaluations. They quote a study by Rutherford (2001), suggesting that women were not accepted as good leaders if they exhibited autocratic, task-oriented, and directive behavior, while this was generally accepted in men. Their paper also discusses women leaders in Malaysia; they mention that this country is slow to advance women in leadership roles due to stereotypical ideas that women are not best suited for these roles. It is librarians and library students coming from these backgrounds who might seek leadership roles in Western countries, and their Western counterparts should be aware of the cultural stereotyping that has tried to keep these women in lower positions. This stereotyping might have caused a lack of confidence and they might not volunteer to lead a team or a committee unless asked.

It is a huge challenge, if not an impossible task, to have visible minorities in leadership roles if they are under-represented in libraries, a challenge that libraries in Canada and other countries should address. And this needs to be done so that visible minorities can play a meaningful role in their societies through all job sectors, not just the government sector. They cannot play a meaningful role in their societies if their jobs just let them live or survive and do not provide them with the challenges they are looking for.

Even though libraries are dominated by women, there aren’t too many women in leadership roles. There could be various reasons for this – personal choices that women make, or a lack of experience in the field – or this could be the result of the choices the administration makes for leadership roles.

Do women leaders have a different leadership style?

Much literature has been published on this subject both inside and outside of the library field. Early literature on female leadership styles is not without bias and gender-stereotyping against women. Women are physically and psychologically different from men and, therefore, will behave differently in different situations when compared to men. If women leaders behave like women they are seen as being too soft. Having said that, if a female leader behaves in a masculine way and concentrates on performance rather than working with employees she immediately gets negative attention. On the other hand, again, when male managers are feminine in their leadership style and have a tendency to nurture, they are seen as better, enhanced leaders (Jogulu and Wood, 2008). When a man demands, the reaction to his leadership style is not so negative and not so swift. On the other hand, a leader who does not manifest masculine perceptions of leadership qualities is not seen as a strong leader either. And some of the challenges faced by female leaders come not from men but from other women who have different perceptions on women leaders. Women leaders have constantly tried to balance their walk between the masculine and feminine styles of leadership in order to be successful. More recent research shows that the differences in leadership styles between men and women are subtle. It is the leadership style of women that is being recommended as the right kind of leadership style by many researchers (Carlie and Eagly, 2007: 133). Carlie and Eagly also point out that the “only consistent difference between female and male managers was that women adopted a more democratic (or participative) style and a less autocratic (or directive) style than men did” (ibid.: 135). But not all women leaders have a democratic style and not all male leaders adopt a directive style. As mentioned previously, today’s organizations’ leaders do not have all the power to act solo. There are usually various committees and groups, internally within the organization and externally through stakeholders, that might regulate, guide or in some cases control a leader’s decision. Like management, leadership, whether it is headed by a man or a woman, is a collaborative effort between various groups of employees within and outside the organization. Library boards, collegiums, and committees play a role big role in a leader’s behavior and, therefore, their style.

Minorities who come into leadership roles in libraries, or anywhere for that matter, should be aware of the different factors that have an effect on leadership, and the majority culture needs to keep in mind that cultural background has an effect on the same. Both groups should also be aware that leadership styles have an impact on turnover rates in organizations.

Lack of good leadership can cause the downturn of an organization. Similarly, a leadership style that has no precedence in an organization can also cause internal disturbance. A leader might exude fabulous qualities to his/her higher-ups, but may not be accepted by the subordinate-level employees. If the subordinates do not believe that this leader can or will be ousted, then they may leave for greener grass instead. While this may not be a common occurrence in academic libraries where librarians are tenured, it could still affect the non-librarian staff. Some turnover is a welcome and healthy change for organizations including libraries, but a high turnover rate can cause too much disruption to everyday activities. While librarians tend to stay in their jobs for long periods of time, other staff may not. The 8Rs study concluded that, generally speaking, the Canadian library workforce is for the most part satisfied with their current employment situation (8Rs Research Team, 2005).

In their article entitled “Are Leadership Styles Linked to Turnover Intention: An Examination in Mainland China? Hsu et al. (2003) found that “there was a significant negative relationship between each component … [of leadership style] … and turnover intention.” Their focus is on turnover rates in China, but this holds true in other countries and across professions. Sellgren et al. (2007) have found that there is a direct correlation between leadership and turnover rates in nursing. A high turnover rate in the nursing industry has been common for many years in countries like England, Canada, and Sweden, but Sellgren et al. found that a lack of good leadership led to a lack of job satisfaction, which had an effect on the work environment, and this might have an effect on turnover. While nothing could be found in the library literature on turnover rates due to leadership styles, there are plenty of articles on retention issues. Many of these focus on hiring minority librarians in libraries and minority students in library programs.

Maintaining the right level of staffing is essential for the success of an organization. In the library context, too much turnover can cause stress on other librarians who may either have to handle parts of the job that are not being currently covered by any position, or may have to become too involved in the processes of recruiting, hiring, and training. This costs money and time and can also delay in work progress.

Minority librarians need to be aware of all the leadership styles discussed in the leadership literature and find their own style, but they also need to practice moving between styles in different situations. This is where leadership becomes an art. Both minority librarians and their Anglo-Saxon cohorts should be aware of the fact that though leadership has some common attributes, “depending upon the cultural value orientations of a given country or set of countries, the meaning of the leadership situation changes from culture to culture” (Triandis, 1993: 181) and therefore they must be willing to adapt.

References

8Rs Research Team, The Future of Human Resources in Canadian Libraries. February 2005. [Web. January 25, 2011.].

Antonakis, John, Cianciolo, Anna T., Sternberg, Robert J. The Nature of Leadership. London: Sage Publications; 2004. [Print].

Australian Bureau of Statistics, Employment in Culture, Australia, 2006: Introduction. 2009. [Web. January 30, 2011].

Government, Australian, Equal Opportunity for Women in the Workplace Agency. February 2009. [Web. January 28, 2011.].

Carlie, Linda L., Eagly, Alice H. Overcoming Resistance to Women Leaders: The Importance of Leadership Style. In: Kellerman Barbara, Rhode Deborah L., eds. Women and Leadership: The State of Play and Strategies for Change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2007:133–135. [Print].

Cawthone, David L., Leadership: The Great Man Theory Revisited - The Editorial. Business Horizons. 1996:1–4. [May-June].

Fullan, Michael. Leading in a Culture of Change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2001. [Print].

Gibson, Christina B. An Investigation of Gender Differences in Leadership Across Four Countries. Journal of International Business Studies. 1995; 26(2):255–279.

Daniel, Goleman, Leadership that Gets Results. Harvard Business Review 78. March 2000.

Griffin, Ricky W., Ebert, Ronald J., Starke, Frederick A., Lang, Melanie D. Business. Toronto: Pearson Canada; 2010. [Print].

Hsu, Jovan, Hsu, Jui-Che, Yan Huang, Shiao, Leong, Leslie, Li, Alan M. Are Leadership Styles Linked to Turnover Intention: An Examination in Mainland China? Journal of American Academy of Business. 2003; 3.1(2):37–43.

Jogulu, Uma D., Wood, Glenice J. A Cross-Cultural Study into Peer Evaluations of Women’s Leadership Effectiveness. Leadership and Organization Development Journal. 2008; 29(7):600–616.

Kakabadse, Andrew, Kakabadse, Nada, Myers, Andrew. Demographics and Leadership Philosophy: Exploring Gender Differences. Journal of Management Development. 1998; 17(5):351–388.

Kirkpatrick, Shelley A., Locke, Edwin A. Leadership: Do Traits Matter? Academy of Management Executive. 1991; 5(2):48–60.

Li, Haipeng. Leadership: An International Perspective. Journal of Library Administration. 2001; 32(3):177–195.

Martin, Susan K. The Profession and its Leaders: Mutual Responsibilities. The Journal of Academic Librarianship. 1996; 22:376–377.

Statistics Online, National, Working Lives. Office for National Statistics. 2011. [September 26, 2008. Web. January 28].

OCLC (Online Computer Library Center, How One Library Pioneer Profoundly Influenced Modern LibrarianshipDewey Services. OCLC, 2011. [Web. October 24, 2011].

Paterson, Kimberly. I’m Leading - Why Aren’t They Following? Part 1. Rough Notes. 2010; 153(12):100, 102–103.

Rutherford, Sarah. Any Difference? An Analysis of Gender and Divisional Management Styles in a Large Airline. Gender Work and Organization. 2001; 8(3):326–345.

Schubert, James N. Age and Active-Passive Leadership Style. The American Political Science Review. 1988; 82(3):763–772. [Web. January 30, 2011].

Sellgren, Stina, Ekvall, Goran, Tomson, Goran. Nursing Staff Turnover: Does Leadership Matter? Leadership in Health Services. 2007; 20(3):169–183.

Statistics Canada, Women in Canada: Work Chapter Updates. 2007. [April 20. Web. January 28].

Triandis, Harry C. The Contingency Model in Cross-Cultural Perspective. In: Chemers Marin M., Ayman Roya, eds. Leadership Theory and Research. New York: Academic Press; 1993:167–185. [Print].

United States Department of Labor, Statistics and Data: Quick Stats on Women Workers. 2009. [Web. January 28, 2011.].

Vinnicombe, Susan, Kakabadse, Andrew. The Debate: Do Men and Women have Different Leadership Styles? Manangement Focus. 12, 1999.

Weiner, Sharon Gray. Leadership of Academic Libraries: A Literature Review. Educational Libraries. 2003; 26(2):5–18.

Wiegand, Wayne A. A Biography of Melvil Dewey: Irrepressible Reformer. Chicago: American Library Association; 1996. [Print].

Winston, Mark D. The Importance of Leadership Diversity: The Relationship between Diversity and Organizational Success in the Academic Environment. College and Research Libraries. 2001; 62(6):517–526.

Wolinski, Steve. Leadership Theories. Blog: Leadership; 2010. [April].