Leadership skills

Abstract:

Some of the major skills required for leaders are: motivational skills; communication skills; time-management skills; fiscal skills; and conceptual skills. Every style has its own set of skills associated with it. An autocratic leader is skilled at accomplishing tasks by demanding work from subordinates and might actually be successful in some cultures and organizations; a democratic leader is successful with his/her people skills and gets the job done. Learning and honing these skills and styles, and using them at the right time in the right place at the right level, will help leaders in their path to success.

Motivational skills were discussed in Chapter 2. A leader’s ability to be self-motivated and motivate others is not only extremely desirable, but required. Apart from motivational skills, which are indispensable in a leader, there are also other important leadership skills such as time-management, communication, conceptual or decision-making skills, critical thinking skills, fiscal skills, and people skills, along with the ability to be extremely organized.

Time management and being organized

Time management and being organized go hand in hand. Being a leader means juggling a variety of issues on any given day, all of them important to the people that are waiting for a response. In Western culture, one often hears clichés such as “time is money,” “there is no time like the present,” and “time is of the essence,” clichés that have created a society in which “time constraints” are unlimited. Bills have to be paid on time, children have to be dropped off and picked up on time, and projects have to be completed on time – because other people involved in these activities can be affected by delays and this is not acceptable in Western culture. Librarians coming from different cultures have different senses of time. In Canada, if a person is asked to come for supper at 6 p.m., he/she is at the door at almost 6 p.m., or a few minutes after. In India, it would be considered inappropriate to arrive at the time indicated (at least in a social setting) and generally guests don’t arrive for at least an hour after the scheduled time. Time is not specific and is not “urgent” in many Asian cultures. A verbal invitation for lunch or supper might just indicate that the guests come either this day or that. Anyone who watched the Commonwealth Games in September 2010 in India would have realized that “Indian time” is completely unrelated to the Western sense of time. Probably due to this, the country was unprepared on the opening day of the games. While sanitation issues and human rights issues surfaced during this time, it was also clear that due to the concept of “Indian time” the organizers and committees involved did not do enough to prepare the village for the arrival of the guests. One of the senior officials also explained that Westerners had a different idea of sanitation and that complaints were due to cultural differences (Majumder, 2010). In another example, Graham and Lam (2003) discuss the Chinese and Americans negotiating for a telecom deal. The manager of the American company (Tandem Computers) “offered to reduce the price by 5 per cent in exchange for China Telecom’s commitment to sign an order for delivery within one month. The purchasing manager (of China Telecom) responded that there was no need to rush, but since the price was flexible, the price reduction would be acceptable.”

On the subject of culture-specific manifestations of Indian culture, Chhokar (2007: 992) describes the context of time thus:

There is a kind of ambivalence about time and punctuality. Whereas a number of official and business activities do occur in a present, though somewhat flexible, time frame, social activities and functions are often delayed. This ambivalence was attributed by a Western observer to language when he discovered that the word for yesterday and tomorrow in some Indian languages was the same (Kal), and therefore it did not make a difference if a meeting was held yesterday or tomorrow, for example.

Such is the concept of time in India and in many polychronic cultures where life is less structured. In “Culture and Leadership in South Africa,” Booysen and Van Wyk (2007) present a study that exposes the differences in time mentality among black managers and white managers in South Africa due to differences in the perception of time as a concept. While white managers were reported to work within a linear, sequential or monochronic perception of time, black managers see time as cyclical and synchronic. For white managers, time was related to an event and therefore tangible and divisible, whereas those who see time as cyclical tend to see time commitments as desirable rather than absolute (ibid.: 465–466). Ogliastri (2007: 699) speaks of Columbians as people who “generally arrive late for appointments (half an hour is common) although this custom has become less acceptable, and there now exists greater pressure toward being punctual, especially among companies and professionals (doctors and dentists).” In Cultural Intelligence, Earley and Ang (2003: 177) further confirm the fluidity of time when they say that “in the Chinese culture, it is not unusual for wedding banquets to begin two hours later than the designated schedule so that due respect is given to every single guest who took the trouble to make it to the feast.” This lackadaisical attitude towards time is unacceptable in monochronic cultures such as the US, Canada, the UK and Australia. Monochronic societies are economically developed, and treat time as a scarce resource, a resource that has to be used efficiently and purposefully (Hoppe and Bhagat, 2007: 484). The Anglo-Saxon culture lives by the clock and judges people by their ability to be on time and their productivity in the time allotted. Asian, African and other polychronic cultures are more relaxed and non-linear about time. With globalization, business organizations in various countries have realized the importance of the concept of time as understood by the Western world as vital to bringing competitive advantage. They are trying to work with the Western concept of time by attempting to deliver on promised dates, but it remains a challenge.

Immigrant librarians coming from polychronic cultures should be aware of the fact that the Anglo-Saxon world runs by the clock. The calendar and clock dictate a planned and organized future. Often, meetings are scheduled a year ahead of time at timely intervals. Interviews, meetings, social gatherings all start on time and end on time. To be a successful employee, and later a leader, the cyclical sense of time has to be left behind. It is essential to be able to work with deadlines, assume multiple responsibilities within a given period, and efficiently manage time in everyday work. Since time is a major organizational resource, a lack of time-management skills can cause one to lose a job or, at the very least, not to be considered for promotions. Emphasis should be on prioritizing day-to-day and long-term activities and completing projects efficiently and in a timely manner to show aptitude, adeptness, and competency. Managing time efficiently is a positive and required factor in a work environment.

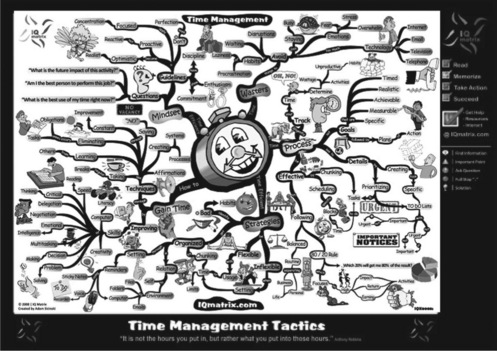

Figure 4.1 IQ matrix: accelerating your human potential Source: from http://blog.iqmatrix.com/mind-map/time-management-mind-map

In this digital era, there are many ways in which one can manage time efficiently. There are gadgets and online technologies that can send reminders. Microsoft Outlook calendars, iPad calendars, cell phones, iPhones can remind users of upcoming assignments. For those with no fancy gadgets, there are also free downloadable aids mentioned by Kumaran and Geary (2011) in their article entitled “Digital Tidbits.” For the organization of work on a daily basis, one can use the digital sticky notes. Most new laptops and desktops come with downloadable sticky notes. If not, a Google search on sticky notes will provide a number of free downloadable programs. A sticky note organized by day will organize each task that needs to be accomplished on any given day, and a sticky note for the whole week gives a broader perspective on what needs to be achieved. This, along with a calendar of information, should help with time management and task completion. As emails arrive, one can also set different folders to save them. This will result in easier retrieval later. This is common knowledge for those from monochronic societies, but many from other cultures are not aware of the requirement of time-management skills as essential in order to be a successful professional.

Time management is also about the effective use of time spent on each activity. There are occasions when outside help will be required to complete a task. Recognition of this, and knowing when to seek help from the right sources, is the next step.

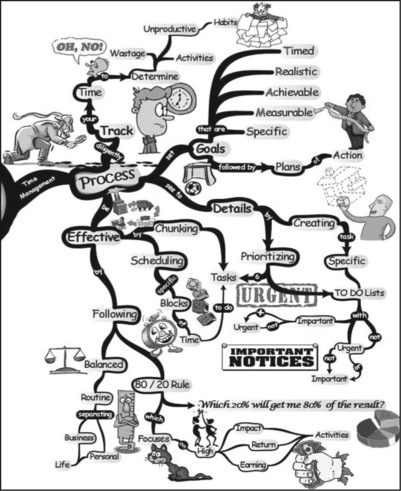

Figure 4.2 Time management process Source: from http://blog.iqmatrix.com/mind-map/time-management-mind-map

Therefore, managing time effectively entails planning, organizing, prioritizing, and executing work in a timely manner, and being flexible to accommodate last-minute changes. Proactive behavior in seeking and using modern tools or gadgets will help in accomplishing the above. Organizational skills come with practice. The more one practices, the better one gets at it.

Communication skills and cultural differences

Communication is vital for any organization. Its internal and external communications play a major role in the everyday activities that lead to success. Communication can be challenging if unclear and untimely. With cross-cultural communications there are additional challenges: information is misunderstood or lost in translation for many reasons, such as ethnocentrism, stereotyping, or confirmation bias. Ethnocentrism is when one judges others by his/her own cultural norms; stereotyping is a commonly known concept that means imposing unfair, unjust generalizations on others; confirmation bias “is the process whereby the bias is confirmed when people see what they expect to see; they are blinded to the positive attributes of others (Locker and Findley, 2009: 108). Cultures have always communicated with and understood each other based on the history between them, and individual biases. Both immigrant workers and their Anglo-Saxon cohorts need to understand the differences in cultural communications.

Edward Hall (1977) defines communication in the terms of context. He says that context and meaning are inextricably bound. He explains high-context communication as a message where information is either in the physical context or internalized in the person, where information is implicit, to be understood clearly by those within the group (or culture) but not by outsiders. Low-context cultures such as Canada, the US and many European countries value the social aspects of communication. In these cultures, it is important to communicate effectively and communicate with a purpose. Information is presented in a logical, detailed, action-oriented, and individualistic manner to inform, persuade, or build goodwill. On the other hand, many Asian and Arab cultures which are high-context cultures see the value of communication in terms of information (Locker and Findley, 2009: 108). This is perhaps the reason why high-context cultures provide information but are not overly concerned about the organization or hierarchy of the information presented. Low-context cultures use direct approaches (what you hear is what you get) and high-context cultures favor “the use of implicit and indirect messages in which meanings are embedded in the person or in the sociocultural context” (Gudykunst et al., 1996). Low-context cultures are individualistic and high-context cultures are predominantly collectivistic. These individualistic and collectivistic approaches affect the style of communication between cultures. In high-context cultures, those within the culture understand unsaid/withheld information. As Triandis observes, collectivist cultures “communicate elliptically, giving just a few clues, and letting the listener ‘fill in the gaps’” and “collectivists emphasize the harmony of the relationship within the ingroup, so they do not confront, but instead use a lot of ‘maybe,’ ‘probably,’ while individualists see nothing wrong with some confrontations that will ‘clear the air’ and tend to use extreme terms such as ‘terrific,’ ‘the biggest’” (Triandis, 1993: 173). In low-context cultures, information has to be clearly verbalized (or written) for others to see or understand. Minority librarians need to learn to communicate like their Anglo-Saxon cohorts and the latter should be aware of the reasons for the differences in communication from their minority cohorts. Asking questions to clarify what was communicated and how it was interpreted by all involved will help with effective communication and prevent misunderstandings on both sides. Zaidman (2011) provides an example of a cultural clash in communication between Israel and India, two very different cultures with different histories and educations. Even though they share a common business language, English, the groups found each other to be either rude or unspecific. To quote Zaidman (ibid.), “Indian English emphasizes humility and politeness, as shown through long, indirect, and poetic sentences” while the Israelis favored a “simple and direct, even forceful” way of communicating.

However, within these cultures not every individual shares the same cultural code and therefore not everyone from a given culture communicates in a similar fashion. There are individuals within high-context cultures who prefer a direct approach and explicit messages. In any culture, the more individualistic an individual is, the more likely a preference for the use of low-context communication styles, and the more collectivistic an individual is, the more likely a preference for the use of high-context communication styles. In addition, the global economy has influenced much of the business communication to follow the ways of low-context cultures. Apart from cultural influences, individual personalities, professional experiences, and personal preferences all play a role in how one communicates.

Kinds of communication

Communication in libraries, as in many organizations, mainly takes place in three different formats: written, verbal, and non-verbal. Written communication consists of emails, memos, meeting minutes, reports, plans, and letters. Verbal communications consist of formal and informal meetings, information through the grapevine, and organizational gossip. Verbal communication takes place in meetings (face-to-face) or over the phone and this may, or may not, be followed by written minutes, depending on the formality of the meeting. Non-verbal communication uses facial expressions, body language, and gestures.

Organizations communicate (both externally and internally) in either written or verbal formats for three reasons: to inform, to persuade or request, and to build goodwill. Memos, reports, plans, and minutes usually inform; emails, letters, and meetings inform, persuade or request, or build goodwill. For the most part, Anglo-Saxon cultures and developed countries have moved away from print communication into the world of electronic communication. Many developing countries are also following suit. Nevertheless, in many of these developing countries, unlike in Western countries, written communication is not viewed in the same way as oral or electronic communication. Many oral cultures, in which printing is not necessarily the preferred or popular form of communication, have a tendency to differentiate their written and oral deliverances. As Griswold (1994: 141) explains, “oral cultures are filled with magic, enchanted with mysterious forces and spirits” and lack a clear boundary between facts and myths. On the other hand, print cultures (such as the Anglo-Saxon dominated cultures) were also literate cultures and developed the ability to differentiate between myth and history early on. There are also cultures where oral communication is as good as the written word. Therefore, a minority living in Anglo-Saxon dominated countries needs to realize that in the Western world, in formal settings, written communication should follow oral communication and both written and oral communications should convey the same message. Mean what you say and say what you mean is a common cliché in the Western world. Facts should be relayed clearly and consistently.

For immigrants who arrive in new cultures, it is going to take time to learn how to communicate effectively in verbal formats. Effective written communication is where ideas are arranged in a logical manner, in order of importance, and organized clearly by headings and subheadings, and where dates, times, and names (of those responsible for action) are mentioned when necessary. When sending emails or preparing reports, information should be relayed clearly and precisely within a described context. It is important to know email etiquette in general, and within the organizational culture. In many organizations, email is considered a formal mode of communication. In some organizational cultures, for information to be considered formal it needs to be typed and signed. Wording in written communication should be unambiguous, timely, and with a clear layout and enough white space. It should be inviting to the reader.

For those nervous about oral communication or public speaking, there is help. There are organizations such as Toastmasters International where one can learn and practice the art of communication in both written and verbal formats. Toastmasters has clubs in India, China, Afghanistan (Kabul), Malaysia, Pakistan, Singapore, many African and South American countries, Australia, the UK, the US, and Canada. Immigrants planning to migrate to their new Anglo-Saxon dominated countries may want to get an early start and visit these clubs in their own countries. Formal oral communication, just as written communication, must organize and present information in a logical and coherent manner. Whether one is communicating to inform or to persuade, it is important to speak with conviction, maintain sincere eye contact, pause in the right places, demonstrate positive body language, and not read from notes. A leader may be nervous, but this should not show when speaking in public. In oral communication, presentation aids or tools such as PowerPoint or Prezi can be used. A quick Google search for presentation aids will offer many tools that are available free of cost. Proper use of handouts and audio-visual aids will keep the audience interested and enhance the presentation.

Remembering the audience is key in communication. Depending on the audience, care should be taken not to oversimplify or over-complicate information that is being communicated. Effective communication, whether in oral or in written format, comes with lots of practice. To be an effective communicator one has to know one’s strengths, weaknesses, preferences, etc. The Western world has also come up with tools that diagnose strengths and weaknesses. Personality indicator tests such as the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator are often used to examine and identify a person’s behavior or style. Myers-Briggs uses four dimensions to identify people and their personalities: introvert–extrovert, sensing–judging, thinking–feeling, and perceiving–judging. Knowing where one fits in a personality indicator test can better enable a person to find their leadership style, communication style, and reasoning behaviors. While many people do not like pigeon-holing or labeling their behaviors and styles, programs such as Myers-Briggs continue to be used as a personality tester to determine characteristics of a personality. Results from these tools should only be taken as suggestions for improvement.

Along with written and verbal communication, non-verbal communication plays a significant role in communication. Non-verbal communication may take the form of gestures or body language and facial expressions, and their meanings differ across the globe. Many successful leaders pay attention to this along with other forms of communication, as words may say one thing and facial expressions may indicate another. Kirch (1979) suggests that Darwin believed that non-verbal communication, especially gestures, developed along the biological line. So, it is safe to say that non-verbal communication is born with us but is shaped by our culture.

Some gestures mean one thing in one culture and another in a different culture. The famous “uh-huh” in North America means “yes” in Canada and the US, but “no” in India. Crossing one’s arms in Western cultures indicates being closed and not interested in receiving ideas from the speaker, but in many Asian cultures such as India’s, it denotes a show of respect and submissiveness. Eye contact is also interpreted differently in various cultures. While many Asian cultures do not look at a member of the opposite sex or an elderly person directly in the eye, in North America, not making eye contact is seen as a sign of dishonesty. Kirch offers other examples of these differences:

Sticking out the tongue may be a form of mockery in the West, but in Polynesia it serves as a greeting and a sign of reverence. Clapping is our way of applauding but in Spain and the Orient it is a means of summoning the waiter. Northern Europeans usually indicate agreement by nodding their heads up and down, and shaking the head from side to side to indicate disagreement. The Greeks have for at least three thousand years used the upward nod for disagreement and the downward nod for agreement.

Electronic communication

In today’s globalized world, many cultures – including developing countries – have started using electronic communication as a formal mode of communication. Email is as formal as the written or typed and signed letter. While electronic communication is quick and timely, it is not always the most efficient way to communicate. But there are situations in which it is useful: sending and receiving resumes and cover letters; informing selected candidates of interview dates, times and other requirements; informing co-workers of updates in the organization, etc.

The chosen channel of communication will depend on various things: the size of the organization; the personal preferences of the communicator; the information to be communicated, etc. Depending on the importance of the message conveyed and its intended audience, the right channel should be used for the right purposes: rejections (for new positions) should not be sent via email, but via typed and signed letters. In addition, there are times when more than one channel may be used to communicate the same information.

Language and communication

Immigrants who arrive in new cultures may speak fluent English, but may not know local colloquialisms and expressions. In this global era of business, most immigrants are familiar with business English and many are masters of the language itself in its grammatical form due to their exposure to the language and their level of education, but some words or expressions can be misinterpreted or taken literally based on cultural meanings or interpretations. Native English speakers also may not understand a word that is entirely English when uttered by an immigrant. Hall (1977) describes an occasion when he was in Italy and heard the word “ferroware” used often in the business with which he was involved. It took him a while to learn that it was a newly created word for all nuts, pates and brackets made of iron or steel. The word was framed along the lines of hardware, software and firmware, words that already exist in the business world. Although, “ferroware” is an English term, it threw him completely because of the lack of context. Language has contextual meanings and emotional connotations for individuals. Even though English is a language many visible minorities are very familiar with, local expressions still might not make any sense due to lack of context. Both native English speakers and English-as-a-second-language speakers should bear this mind when communicating with each other. Communication is mutual interaction between the communicator and the receiver of the information, and this mutual interaction needs various levels of clarification.

To summarize, leaders should know how to communicate clearly so that information is complete, correct, saves time, and produces the desired effect in the reader. In cross-cultural leadership, leaders should be aware of the cultural differences in communication within verbal, non-verbal and written communications. Ask for clarifications when needed and never assume. Poor communication costs time as it takes longer to clarify information, obscures ideas, and causes confusion, it does not get the required results and undermines the image and authority of the leader. Communicating clearly, however, saves time, produces the desired effect, builds goodwill, and maintains the image of a good leader as a great communicator.

Critical thinking skills

Educational institutions from kindergarten schools to universities are focusing on these skills as something to be taught within the curriculum. What is critical thinking? Like leadership, this is another concept that cannot be defined with one or two words. It involves many things such as being open-minded, reasonable, unbiased, unassuming, asking the right questions, identifying issues before they exist, examining the credibility of sources, evaluating and synthesizing information received, being rational, self-aware, honest, and extremely disciplined. This is an important skill for a leader because leaders have to deal with lots of information, with people and with their arguments. Not all information is trustworthy or unbiased, and without the ability to filter and evaluate information leaders cannot function as effective leaders and certainly cannot lead the organization towards success. Leaders should learn not to take information at face value, but to dig deeper to find the hidden meanings or consequences of using that information. When someone tries to persuade a leader with an argument, critical thinking skills will enable the leader to “accurately interpret what they are saying or writing and evaluate whether or not they are giving a good argument …” (Bowell and Kemp, 2005: 3). This essential skill will help a leader identify the issue being argued (or raised), deduce the necessary information from the argument in order to make decisions, evaluate that information, and conclude with results or create a process for achieving results. Logos, or logic, is the important aspect in critical thinking skills, because logical fallacy can lead to polarization – trying to force one to believe that there are only two possible options, only one of which is acceptable; or blindering – limiting options unnecessarily even when aware of other options (Locker and Findley, 2009: 7). Leaders with critical thinking skills will find more than two options and many ways to work with these options. With critical thinking skills, information is already available. On the other hand, having conceptual skills means an abiblity to deal with abstracts.

Conceptual and decision-making skills

Conceptual skills refer “to a person’s ability to think in the abstract, to diagnose and analyse different situations” (Griffin et al., 2011: 188). It is the ability to connect separate concepts or ideas and create a bigger picture; the ability to find the relationship between individual concepts and connect them to a framework to make the best decisions; the ability to come up with creative strategies and solutions before the problem starts. Often a leader is in a situation where there are no facts or evidence upon which to base decisions. In such situations, a leader is expected to make the best possible ingenious and applicable decisions based on experience, the sparse information available, and by being a visionary. Decision-making is a process of finding alternatives and choosing the alternative that works best for the organization and its employers. It is not about being coldly objective in order to produce results. A leader with good conceptual and decision-making skills has the ability to identify potential partners for the organization to provide both moral and financial support. In a library setting, a leader who can identify potential partners at an early stage starts to build relationships, finds new ways of improving library services, and offers better programs and efficient workspaces. In an economic downturn, many countries, even the developed ones, consider shutting down libraries or some library services to save money. This is one situation where a leader’s conceptual skills may save the library, its employees, and users.

When enough information is available a SWOT analysis can be used: to identify the Strengths and Weaknesses of the organization; and the Opportunities and Threats that need to be identified before making a decision. There are many demands and time and money constraints on a leader, and good conceptual skills will help in choosing the right options that will meet those demands and stay within any constraints. As mentioned in the previous chapters, leaders, at least in the library world, no longer have to make decisions without consulting their cohorts. But it is imperative that the leader who has the bigger picture of the organization is able to guide the group’s decision-making process to fit the goals of the organization in the long run, and this cannot be done without conceptual or basic decision-making skills.

Fiscal skills

Many of the decisions a leader makes may involve money management. Offering library programs, creating a new librarian or staff position and hiring for that position, providing training, allowing a library employee to be away at conferences, training, providing research funding or sabbaticals, all cost money. Hence, managing money is also an important skill for leaders. After establishing external relationships, a leader has to show how effectively he or she can run the organization by making the right decisions based on many things, but most importantly based on the money spent by the organization. Learning to budget and knowing how to spend money effectively shows that the leader is being financially responsible. It is not a bad idea for anyone in a leadership position to take a course in managerial and/or financial accounting, so that they understand how money is spent both internally and externally to help with decision-making.

Managerial accounting, also known as cost accounting, helps internal decision-makers. Jones et al. (2003: 2) define it as “the process of identification, measurement, accumulation, analysis, preparation, interpretation and communication of financial information used by management to plan, evaluate, and control an organization.” Although a leader may not be directly involved in spending funds for collections and pay checks etc., a leader is finally accountable for anything that happens with these funds. If a library declares a lack of funds and does not improve its collections or hire new staff, the leader shares the blame for not managing monies appropriately.

Financial accounting is collecting, recording, and presenting financial information to external agencies such as the government, shareholders, and creditors. This is a mandatory accounting exercise in all organizations as it is important to be accountable to all external partnerships.

Every organization has goals. Many involve financial commitments. In a library setting, adding to the physical or electronic collection or hiring new staff, including librarians, are examples of goals that cost money. Organizations set their goals with the help of strategic planning – a long-range plan that outlines actions to be taken in order to achieve the set goals. Libraries, like many organizations, typically have 3–5-year strategic plans that complement their parent organization’s strategic plans. For example, a university library will have a strategic plan that is built around the university’s strategic plan and a school library will have a strategic plan that supports the school’s or school board’s strategic plan.

A good strategic plan involves input from all essential partners, provides a timeframe, lays out the action plans, sets objectives to be achieved, and details the personnel who will undertake or lead these actions. This clear planning helps an organization set aside money, time, and staff to achieve its goals. A leader may not be involved in every step of this strategic plan but has responsibility for the outcome of the plan. An efficient plan can be put together by a leader who has an understanding of the availability of present and future funds for the organization.

A leader should be knowledgable about the organization’s operating and capital budget. Again, the dean or the director of a library is not necessarily involved in the day-to-day operating budget (delivery trucks, inter-library loan charges, fines paid, electricity bills, etc.) nor the long-term capital budget expenses (buying self-checkout machines, a new library building, new land for the library) but will have a major input in the decision-making process of what and where to buy. Without being aware of the funding situation, a leader cannot make the right decisions on how to proceed. Leaders should also learn to be financial managers and manage cash flow, assume financial control, and be involved in financial planning even if they are not directly involved with the money. In today’s economy financial planning is important for libraries. A financial plan “describes a firm’s strategies for reaching some future financial position” (Griffin et al., 2011: 654), and libraries are constantly trying to find ways to fund their projects via outside environments.

In many cultures, women are not the money managers in their families. Men have control of the money and women librarians coming from these cultures may not be comfortable with handling large amounts of money. It is beneficial to take basic lessons on money management, management accounting, and accounting practices, and learn from the financial manager of the institution, colleagues, and mentors.

Technical skills

To communicate effectively and get everyday work done in a timely manner, leaders need to be technically astute as well. Technology is ubiquitous and ever-changing. No one, including the leader, is expected to know how to use every type of technology that comes their way (e.g., iPad, iPhone, wiki, blogs, etc.), but leaders should be able to adapt to and learn new technology quickly. They should be proactive in learning to use new tools. As a leader, it is important not to be technically handicapped or dependent on others. Being aware of new technologies and learning to use them can help a leader keep in touch with others and allow for the fast and efficient flow of information, which can save time and money. Many libraries, especially public and school libraries, are slow in using emerging technologies due to a lack of funds. Many academic and college libraries provide the funds, resources, and training for buying and using the latest technologies. Websites such as YouTube also offer free demonstrations on how to use some of the new technologies in the market. In many cases a new technological tool can be learnt by doing (especially helpful when available free of cost). A leader might have to create a presentation, write a speech, or schedule meetings. Knowing the right tool to use and knowing how to create a presentation can make the information clear and even influential. It is understandable that some of the ethnic minorities may not be familiar with all the technologies of the developed world, but a willingness to learn is key.

Human relations skills (or people skills)

Skillful human relations is the ability to get along with other people, and this cannot be achieved without empathy, good communication skills, and an understanding of the diversity that exists: diversity in people’s behavior, cultures, gender, age, beliefs, religious, educational, and socio-economic backgrounds. Human relations is different from human resources skills. Human resources is a “set of organizational skills directed at attracting, developing, and maintaining an effective workforce” (ibid.: 242). While it is important to have a stable human resources plan in order to find, hire, and keep an effective workforce, a good leader should also possess human relations skills in order to maintain and sustain a productive workforce.

As Mullins and Linehan (2005: 137) explain, “The ability to get on with people, at all levels, would be one of the main qualities required of any library leader, and this includes relating with the pubic, with library staff, and with management staff of the local authority.” They also go on to say that having good people skills means having good communication skills, good listening skills, and being a good talker. A leader without human relations skills has no understanding of the needs of his or her employees and is therefore incapable of empathizing with and motivating employees to achieve their fullest potential both individually and collectively for the organization’s success. Lack of human relation skills in a leader can cause high turnover, break goodwill among internal and external organizational partners, and eventually contribute to the failure of the organization.

Lately, a skill that has been identified as very important is that of reflective practice. This is the ability to stop and think critically about what one is doing. Lambert (2003: 6) defines it as “the genesis of innovation.” Literature on reflective practice identifies this skill as a crucial way to understand oneself, and one which will enable a better understanding of others. The idea of the importance of this skill is not new but is gaining momentum again. In 1984, Kolb popularized the relationship between reflection and learning. Schön (1987) explains reflection as:

Diagnosis, testing and belief in personal causation. Diagnosis is the ability to frame or make sense of a problem through use of professional knowledge, past experience, the uniqueness of the setting and the people involved, and expectations held by others. Once framed, the reflective practitioner engages in on-the-spot experimentation and reflection to test alternative solutions.

Libraries are dynamically changing organizations that strive to meet the demands of their communities with information and technology. Library leaders work under a constant challenge of being able to meet these demands, and can easily get held up in “doing” something and forget to think about the process: the before and after. Reflecting on the before and after will shed light on the gaps that can be filled, other external factors that needed to be assessed, and the long-term implications of decisions.

In any given organization, there are people with different skills and abilities. A leader with good human resources skills should be able to identify these skills and capitalize on them. Getting to know one’s employees, their work preferences, any personal problems (that they are willing to share) that might be affecting their performance, will help a leader understand and relate to each of the employees differently. In the case of ethnic minorities who come from different countries, there could be lots of personal issues: a lack of friends and family nearby, feelings of homesickness, and in some cases lack of money, are some of the issues that could be bothering them in their everyday lives. Many do not get the chance to visit their families often and anything that might be happening in their birth country could be affecting their performance. In cross-cultural leadership this is an important factor to consider. In order to avoid major setbacks due to personal problems it helps to clarify the role of each employee within the organization, and to set clear goals for performance on a timely basis both for individual employees and for the organization as a whole. As mentioned above, strategic plans can be used when defining personal goals for employees.

To conclude, leaders need to possess many skills and know how to use the right one in the right situation. Leadership is a learning process and good leaders are dynamic. To quote Mullins and Linehan again: “Personal qualities are not fixed within individuals as they can change through influence, continued education, training, experience, as well as fluctuating within individuals, such as changing personal circumstances, or the impact of mentors and other colleagues” (Mullins and Linehan, 2005: 134).

Learning and building these skills, and being adaptive to changes, will pave the way to becoming a good leader and enable the leader to nurture, have an insight into employee issues, and be innovative with problem solving and decision-making. Once good foundational skills are built, efforts should be taken to maintain and acquire more skills – exploring the unknown. Humility, self-awareness, and a willingness to adapt will all help in one’s journey towards leadership.

References

Booysen, Lize A.E., van Wyk, Marius W. Culture and Leadership in South Africa. In: Chhokar Jagdeep S., Brodbeck Felix C., House Robert J., eds. Culture and Leadership Across the World: The Globe Book of In-Depth Studies of 25 Societies. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2007:433–474. [Print].

Bowell, Tracy, Kemp, Gary. Critical Thinking: A Concise Guide. London: Taylor & Francis; 2005.

Chhokar, Jagdeep S. India: Diversity and Complexity in Action. In: Chhokar Jagdeep S., Brodbeck Felix C., House Robert J., eds. Culture and Leadership Across the World: The Globe Book of In-Depth Studies of 25 Societies. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2007:971–1020. [Print].

Earley, Christopher P., Ang, Soon. Cultural Intelligence: Individual Interactions Across Cultures. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 2003. [Print].

Edwards, George. It’s OK, They All Speak English. European Business Review. 1990; 90(3):8–12. [Print].

Graham, John L., Mark Lam, N. The Chinese Negotiation. Harvard Business Review. October 2003; 82–91.

Griffin, Ricky W. Business. Toronto: Pearson Canada; 2011. [Print].

Griswold, Wendy. Cultures and Societies in a Changing World. Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press; 1994. [Print].

Gudykunst, William B., Matsumoto, Yuko, Ting-Toomey, Stella, Nishida, Tsukasa, Kim, Kwangsu, Heyman, Sam. The Influence of Cultural Individualism-Collectivism, Self Construals, and Individual Values on Communication Styles across Cultures. Human Communication Research. 1996; 22(4):510–543. [Print].

Hall, Edward T. Beyond Culture. Toronto: Random House of Canada; 1977. [Print].

Hoppe, Michael H., Bhagat, Rabi S. Leadership in the United States of America: The Leader as a Cultural Hero. In: Chhokar Jagdeep S., Brodbeck Felix C., House Robert J., eds. Culture and Leadership Across the World: The Globe Book of In-Depth Studies of 25 Societies. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2007:474–543. [Print].

Jones, Kumen H., Werner, Michael L., Terrell, Katherine P., Terrell, Robert L., Norwood, Peter R. Introduction to Management Accounting. Toronto: Prentice Hall; 2003. [Print].

Kirch, Max S. Non-Verbal Communication Across Cultures. The Modern Language Journal. 1979; 63(8):416–423. [Print].

Kolb, David A. Experiential Learning. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall; 1984. [Print].

Kumaran, Maha, Geary, Joe. Digital Tidbits. Computers in Libraries. 2011; 31.1:11–15. [38–39. Print].

Lambert, Linda. Leadership Redefined: An Evocative Context for Teacher Leadership. School Leadership and Management. 2003; 23.4:421–430.

Locker, Kitty, Findley, Isobel. Business Communication Now. Canada: McGraw Hill Ryerson; 2009. [Print].

Majumder, Sanjoy, Commonwealth Games: India Vows to Fix Delhi Village. September 2010. [Web. February 14, 2011].

Mullins, John, Linehan, Margaret. Desired Qualities of Public Library Leaders. Leadership and Organization Development Journal. 2005; 27.2:133–143.

Ogliastri, Enrique. Colombia: The Human Relations Side of Enterprise. In: Chhokar Jagdeep S., Brodbeck Felix C., House Robert J., eds. Culture and Leadership Across the World: The Globe Book of In-Depth Studies of 25 Societies. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2007:689–722. [Print].

Schön, Donald A. Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Print].

Triandis, Harry C. The Contingency Model in Cross-Cultural Perspective. In: Chemers Martin M., Ayman Roya, eds. Leadership Theory and Research: Perspectives and Directions. New York: Academic Press, Inc; 1993:167–185. [Print].

Zaidman, Nurit. Cultural Codes and Language Strategies in Business Communication. Management of Communication Quarterly. 2011; 14.3:408–441.