Introduction

Abstract: Canada, Australia, the UK, and the US have a considerable number of minority immigrants and many more continue to move there. The social make-up of these immigrants has changed from earlier times – there are more from Asia, Africa, and the Middle-East moving to these countries. These immigrants, in spite of their education and experience from their home countries, often have a difficult time finding jobs and settling in, let alone trying to be leaders in their field. They need help in securing a place in the community, finding a job that they are trained for, and then becoming leaders in their organization. This is minority leadership and it is different from cross-cultural leadership. There are also differences between a first generation immigrant minority leader and leaders from the second or third generation immigrant population. While the last two identify themselves with what is their native culture, first generation immigrants are still torn between their native culture and the new culture in which they live. This may not be true of all immigrant minorities – some seek and find opportunities and flourish quickly, others take a long time, and many just focus on their children’s futures.

Key words: minority leaders, minority leadership, crosscultural leadership, visible minorities, minority leadership literature, Australia, UK, United States, Canada, diversity

In the fall of 2009, when I was still the Virtual Reference Librarian at the Saskatoon Public Library (SPL) in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada, I had the opportunity to attend the Leadership Development Program organized by the City, funded by my employer (for me) and offered through the Edwards School of Business, University of Saskatchewan. It was an eight-week session (one evening a week) covering a range of topics from Understanding Leadership, Emotional Intelligence, Encouraging the Heart, and being a role model as a leader. The program was taught by various facilitators and attended by people from various job fields – a physician, a soup-kitchen manager, police officer, manager of a senior home, City workers and myself, the only librarian.

I am fascinated by the idea of leadership in the Western countries and our obsession with it, but was also disappointed that none of the facilitators could tell me anything about ethnic-minority leadership. This is Canada, a multicultural country, where in 2002 there were 3 million visible minorities who represented 13 per cent of the non-aboriginal population aged 15 years and older (Statistics Canada, 2003). In 2006, 5,068,100 individuals called themselves visible minorities (Statistics Canada, 2010).

What is ethnic-minority leadership?

Ethnic-minority leadership is different from cross-cultural leadership. Cross-cultural leadership issues generally focus on a leader from the Anglo-Saxon culture learning about the nuances of the cultures they have to do business with to be successful and profitable. It focuses on this leader’s ability to incorporate the kaleidoscopic nature of the cultural variables into their everyday business activities. Ethnic-minority leadership is about identifying potential candidates from minority groups within Anglo-Saxon cultures to become leaders in whatever field they are in and providing them with the support and training necessary. This could mean upgrading their education, technical, language or leadership skills, or simply encouraging them to live up to their fullest potential at work and recognizing them for their contributions.

Who are visible minorities?

The Employment Equity Act (1995) defines visible minorities as “persons, other than Aboriginal peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour” (s.3). The Commission for Racial Equality, a public body from the UK that deals with racial discrimination and which has merged to become the new Equality Human Rights Commission, states that “visibility is a vague term that could refer to a number of things including phenotype [observable characteristics] accent, dress and name” (Office for National Statistics, 2007). These statistics include visible minorities of all generations.

So, why focus on these new immigrant visible minorities?

Note that the terms ethnic minorities, visible minorities, new immigrants, immigrants, are all being used interchangeably and they all mean minorities living in majority white countries.

In 2005, the Toronto City Summit Alliance, a coalition of civic leaders that focuses on many initiatives in the City including DiverseCity in Toronto in Canada, reported, “Immigrants already provide 60 per cent of our population growth. By 2020, they will supply 100 per cent” (Siddiqui, 2005). Statistics Canada (2005) adds that “roughly one out of every five people in Canada, or between 19 per cent and 23 per cent of the nation’s population, could be a member of a visible minority by 2017 when Canada celebrates its 150th anniversary … Canada would have between 6.3 million and 8.5 million visible minorities 12 years from now.” Canada is not the only country experiencing immigration growth with a focus on visible minorities. Australia, another multicultural country similar to Canada, also reports a growth in its immigrant population. Immigration has also been a significant factor in contributing to Australia’s population growth but has been more volatile. In 1993, immigration contributed about 23.1 per cent to population growth and in 2008, this rose to 59.5 per cent (Australian Government, 2009). According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), the immigrant landscape has changed in Australia as well. It is not just immigrants from English speaking countries that arrive to live in Australia; in 2007, of the 647,000 immigrants “the majority (76 per cent) were born in other than main English speaking countries.” People born in the UK contributed to the largest group of overseas-born Australian residents, closely followed by China, India and Italy, in that order, in large numbers.

In the United Kingdom, in 2001, 4.9 million (8.3 per cent) of the total UK population was born overseas and an estimated 223,000 more people migrated to the UK in 2004 (Office for National Statistics, 2005). BBC news reported that “people born in Asian or African countries accounted for 40 per cent and 32 per cent respectively of all applications, the principal nationalities being Pakistani, Indian and Somalian” (News, 2006). In the United States, where multiculturalism is not a clearly established policy at the federal level, “slightly more than half (53 per cent) of resident non-immigrants were citizens of Asian countries” (Baker, 2010). The United States also has a healthy Latino and African-American population who are visible minorities. People have always migrated to the United States, Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom, but recently the social make-up of immigrants coming to these countries has changed. It is no longer Europeans moving between countries, but the non-Caucasians from different countries that come from different age groups, with different levels of education, economic background and status (refugees) that constitute the new immigrant population in all these countries and they are the very visible minorities.

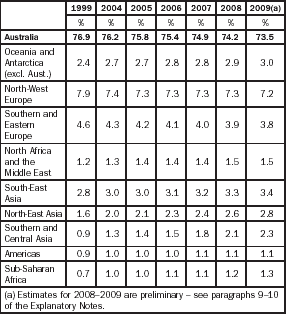

Table I.1

Regions of birth, proportion of Australia’s population – selected years at 30 June

Source: ABS: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Products/0549A6756B213B25CA25776E00178A59?opendocument

Considering the number of visible minorities that live in these countries, especially here in Canada, it is baffling and perhaps even shameful that there was not much literature on minority leadership. After all, many of these minority immigrants would or could have been leaders in their profession or their community at some point in their lives.

Focus of this book

This book will focus on visible minorities as in those who are non-Caucasian and have certain obvious characteristics that set them apart, such as accent, dress, etc., who work in the field of libraries and information sciences. Although visible minorities of all generations will find this book useful, first generation visible minorities will find it particularly useful and relevant to their work experiences. This is because, even though the second and third generation visible minorities are visible minorities, they do not see themselves in the same way as do first generation minorities who are trying or struggling to fit in. In spite of the differences in physical appearances, if any, second and third generation visible minorities are citizens of the country that their parents or grandparents emigrated to and have assimilated into the culture of the country in which they were born, in terms of education and cultural and professional experience. Because of this, they do not face the same challenges that first generation visible minorities do. One major challenge that first generation visible minorities face is the cultural differences between themselves and their new host country. The book does not focus on Aboriginal populations or smaller populations who have lived within a country for many generations, such as French Canadians in Canada, but touches on challenges faced by African-American populations in spite of having lived in the US, the UK or Canada for generations. Indigenous populations in Australia, the United States and Canada will need whole books dedicated to the challenges they face as minority groups and how this may have an effect on their leadership skills and abilities.

Not long ago, Barack Obama, a visible minority in the United States of America, was contending to be the President of the country. The world was watching because, not only was America having its elections, but also a black man was trying to be the leader of that country for the first time in its history. Although he was of mixed race (white mother and a Kenyan father), and was raised by his mother, Stanley Ann Dunham and her family, he was seen as the black man, a visible minority. He did not have the experience or a glorious resume like his competitors (example: Hilary Clinton), and yet, due to various different factors that played a big role in the election campaign, he won. To the world watching, what was obvious during this election campaign was that it is not easy for a visible minority to assume a leadership role in a country where the majority of the population is white. Readers should know that Obama was born in Honolulu, Hawaii, in the United States. His father was a student in the United States and married his mother Ann, an American citizen, and so Obama is both a first generation immigrant and a visible minority due to his African-American appearance and roots. If he had had a Ukrainian or Serbian father, he would not have qualified as a first generation visible minority. If becoming a leader can be challenging in itself, becoming a leader as a visible minority is even more challenging as seen in Obama’s election campaign.

While the political leadership role is about securing votes from different population groups by earning their respect, leadership in libraries is about many things including that, and also education, experience, confidence, being collaborative, being accepted and finding the right opportunities both within and outside of the library field. Leadership is also about the willingness of the individual to become a leader and the willingness of the society (in this case the information field or the organization, such as an academic or public library) in accepting an individual as their leader.

Ethnic minorities who come to Western countries as new immigrants have many hurdles to jump through. The processes they have to go through (paper work, medical check-ups, and police records checks) to get to their new countries are disheartening and tiring. Once they are in their new countries, their educational or professional credentials from their home country are quite often not recognized by their new country. They need to upgrade their education, which they cannot do without money, they cannot have money without a job and they cannot have a job without a proper education. It becomes a vicious cycle, one which they need to find a way out of before they can consider leadership. It is not due to lack of education that they cannot find jobs; it is due to lack of recognition and acceptance of their education: “Visible minority population is generally more educated than the rest of the Canadian population. In 2001, 23.6 per cent of visible minorities held a university degree, compared to 14.2 per cent of non-visible minorities … despite being more highly educated than non-visible minorities, visible minorities have higher unemployment rates than their counterparts” (Perreault, 2004). It is no wonder that many of these highly educated visible minorities live below the low-income threshold (ibid.). Another daunting concern is the cultural differences they face. They may have a strong accent or have trouble speaking in a way that locals understand. Dr Tien (1998: 34) states that people in the United States find European accents to be prestigious but Asian or Latino accents make their “owners” seem ignorant, uneducated and unequal. Many of these visible minorities can speak grammatically perfect English, but perhaps not the way local folks understand them.

On my very first day in Canada I was taken to Dairy Queen (a fast-food joint) for lunch. The person who took me there ordered for me and left me to wait in line for my food. The woman at the counter asked me a question and all I could understand was that it had something to do with “Sunday.” I assumed she was asking if I wanted to get my food on Sunday (this being Thursday) and replied that I wanted it today. She was puzzled and pointed to the ice cream beside her. I had no idea that there was an ice cream called “sundae.” Accent and lack of knowledge of local food were my barriers, not lack of language. After 16 years of living here, I have acquired and mastered this accent to the extent that colleagues are surprised when I mention I had most of my education in India. They assume I moved here at a very young age.

So, because of these simple yet surmountable hurdles that many immigrants face in their new lives, immigrants have more challenges and may or may not be interested in a perfect job that nurtures them to be leaders. Their focus might just be on survival and nurturing their future generation. Unless there is help, they may not think of leadership as an option for them at all. If they don’t, then the leadership of countries such as Australia will not be an appropriate representation of their demographics.

Diversity in diversity

Individuals within these diverse cultures are not alike. They differ in their personalities, because of where they are from and what they believe in, in their financial and legal status in their new and home country, in their education, religious beliefs and age. There are differences in psychological and emotional attributes that vary from one human being to another regardless of their backgrounds and current living conditions. It is important for all involved (minority groups and Anglo-Saxons) to remember that not all minority groups or individuals within a group are the same. There are many differences between the different people who come from various countries in Africa, and the same applies for the population that comes from one country in India.

Minority leadership

Once ethnic minorities manage to cross over the above-mentioned hurdles, and manage to accomplish goals and make their way towards leadership, there are still challenges to face. There are stereotypes about minority leaders: they can only lead minority followers; they lack confidence or skills that white leaders have; they are ignorant of their new culture and only do things the way they did in their own culture. The following chapters in this book will attempt to dispel such stereotyping and myths about minority leaders and their ability to adapt to their new majority culture, and will attempt to highlight the kind of cultural strengths they bring with them. The following chapters will also help minority leaders overcome their fears and find ways to become leaders in their fields, particularly in the library and information fields.

Literature on minority leadership in libraries

In library literature, most of the articles about ethnic or visible minorities focus on the subject of collections or programing for multicultural populations, but not much on building leadership skills in ethnic minorities. American librarians have written about librarians of color and their struggle to find jobs or become leaders. Riggs (1999) mentions the lack of leadership literature in libraries prior to 1981. Since then, many articles and books have emerged on library leadership, but as Weiner (2003: 14) observed, “it is clear that many aspects [of leadership] have not been addressed and that a comprehensive body of cohesive, evidence-based research is needed.” By “aspects” Weiner refers to the different characteristics, styles and skills that make a leader; I would like to include ethnic-minority leadership as an aspect. Or, it can be considered one “facet” of library leadership that has not had enough attention from leadership writers. When speaking of diversity issues in the same article, Weiner only mentions male and female leaders, not ethnic leadership.

Some efforts to focus on this aspect of leadership are already under way or well established: for example, the American Library Association (ALA) and Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) and their efforts to improve retention, recruitment and advancement of librarians of color. ALA established the Spectrum Scholarship Program in 1997; a program that focuses on recruiting under-represented ethnic-minority librarians into the profession. The Association of Research Libraries (ARL) launched its Leadership and Career Development Program (LCDP) in 1997. This 18-month program prepares under-represented librarians from different ethnic groups for leadership roles in ARL libraries. Since ARL has Canadian and US research-extensive institutions as its members, this program is also available for Canadian librarians who are interested. I have not had any luck finding similar programs in Australia or the UK.

I can hear readers asking, “Why should there be a different program or book for ethnic-minority librarians? Why don’t they take the same programs as other Americans, Canadians or Australians?” There are three major reasons: 1) many of the leadership programs are tailored for the majority culture, for participants who are familiar with the rights and wrongs and dos and don’ts of their own culture; 2) libraries themselves have European/American value. Although many cultures have had and continue to have libraries, libraries of the Western culture have their own values. They play an integral role in informing, educating and entertaining the haves and have-nots of their societies with a number of free services and programs. Ethnic minorities in their new homes should understand both the culture of their new land and the value of libraries there; (3) the concept of “leadership” varies in different countries. While there are some commonalities of this concept of leadership among various countries, there are differences as well. Many countries would define a leader as honest and trustworthy, and other countries expect their leaders to have experience and therefore be wise. Some cultures see a leader as being authoritative, having the final say in matters, and other cultures see a leader as part of a decision-making group. A single facet of leadership does not appeal to all cultures uniformly.

Some of the first generation immigrants will land in library professions and will need a handbook of leadership etiquette. First generation immigrants are used to different orientations, contexts, and sense of time, and many, many, many cultural differences that add to the already confusing concept of leadership. Both immigrants and their Anglo-Saxon cohorts need to understand the cultural differences that affect leadership styles and skills in order to be well-rounded, efficient leaders in ethnic-minority leadership situations, and I hope that this book will be the first stepping stone towards such an understanding.

Chapter 1, entitled Leadership as defined by culture, profession and gender, clarifies that a definition of leadership is not possible due to various factors that go into building a leader. There are cultural, socio-economic, political, religious, and various other influences, and these have an influence on a leader’s performance and behavior. However, it is important as an ethnic-minority librarian to be aware of these influences and self-evaluate.

Chapter 2 attempts to differentiate between leaders and managers. Although leadership is almost indefinable, there are qualities that make leaders who they are and these qualities are different to what is required from managers. Ideally, all managers should be leaders and all leaders should have managerial abilities. Having said that, there is a distinction between these two qualities, and this chapter outlines them. One important thing to remember is that leadership is not about a title. Anyone within an organization can be a leader: take initiative, offer creative solutions, foresee problems, be visionaries, establish goals for self-improvement, encourage and enable other employees. Being visionaries and foreseeing problems come with experience.

Chapter 3 focuses on leadership styles. Leaders come with many styles: authoritative, democratic, pace-setting, coaching, coercive, etc. Each style has a time and a place. There were and continue to be many theories on leadership and some of these theories established certain styles as requirements for leaders. In the early days, the Great Man theory indicated that leaders were born. They came from aristocratic or rich families, were educated and well respected in the community. Trait theory, behavioral theory, contingency theory and situational theory have their own take on leadership styles. Trait theory expected leaders to have certain characteristics and implied that one just had to have distinguishing traits to be a leader. Behavioral theory suggested that leaders were defined by their behavior. Task-oriented or task-focused behavior and good people skills were great qualities, but these alone did not make one a good leader. Many task-oriented employees in an organization are keen on accomplishing tasks, but have no leadership skills or interests. Leadership goes beyond accomplishing tasks. Situational and contingency theory focused on the situation that would cause or mold a leader. A situation defines a leader and the effectiveness of a leader is contingent on how well a leader’s style works for the organization. These theories and styles will continue to evolve as libraries move more and more towards virtual environments, where body language is absent. In such a scenario, one has to refine communicating styles, conceptual skills, and time-management skills to work with various time zones and timelines for different projects and have exceptional people skills to reach their virtual partners. Motivational skills – the ability to be self-motivated and the ability to motivate others – are required skills in a leader.

Chapter 4 focuses on some of the indispensable skills for anyone in a leadership position. Multitasking abilities are expected from all employees and as a leader one has to multitask efficiently without losing focus, as there are many tasks and deadlines. Leaders need to have effective time-management skills and be extremely organized. In Western culture, time-management is an important skill. One of the first things foreign students learn in universities during their orientation sessions is the importance of “time” in Western culture. Assignments have to be submitted on time, classes start on time and even public events and social occasions start and end on time. For immigrants coming from many parts of Asia, Africa and the Middle East, these rigid “time” rules are unusual, especially in public and social settings. The polychronic attitude towards time needs to be left behind to succeed in any career in the Anglo-Saxon culture. Critical thinking skills, conceptual skills, decision-making skills, communication skills, fiscal skills, and people skills are all important skills to learn and use. The communication of information differs between cultures. Some cultures see effective communication as essential and value the social aspects of communication, and others see its value only in terms of information.

Chapter 5 looks at library leadership in three major library types: academic, school and public libraries. While there are many articles on the leadership trends and issues in academic libraries, there is not much literature on the leadership issues and trends in public and school libraries. This disparity could be due to various factors. One such factor is that academic librarians are expected to publish. Public and school librarians generally are not expected to publish. School libraries have a limited number of journals dedicated to their issues. But recent literature on all three libraries suggests that there is an interest in leadership issues. While there are some articles in the academic field that focus on minority leadership in their libraries, it would prove challenging to find such material on public and school libraries. Chapter 5 also provides details on the survey conducted among ethnic-minority librarians, deans and directors of libraries, and directors of library schools in the UK, the US, Canada, and Australia.

Conclusions

For some, leadership comes naturally. For many others, leadership is confusing. There are traits, skills, styles, and behaviors, and all of these are influenced by the individual’s cultural, socio-economic, religious, and educational backgrounds. There are values that good leaders have or are expected to have. With minority immigrants there are two layers of culture – the culture they are from and the culture to which they have to adapt – to tackle, and this is not always an easy task. There could also be language issues. Leadership is a learning experience and it takes time, effort, and lots of patience by all involved for an ethnic minority to become a successful leader and to stay in that position.

References

American Library Association. Spectrum Scholarship Program, 2010. [Web. October 13].

Australian Bureau of Statistics, 3412.0 – Migration, Australia, 2008–09. Regions of Birth. 2010. [Web. August].

Australian Bureau of Statistics, Labour Force Status and Other Characteristics of Recent Migrants. 2010. [6250.0, Australia, November 2007.Web., September 12].

Australian Bureau of Statistics, 3412.0 – Migration, 2008–09. 2011. [Web. April 12].

Australian Government, Department of Immigration and Citizenship. Population Flows: Immigration Aspects, 2007–08 Edition. 2009. 2010. [Web. September 21].

Baker, C. Bryan, Estimates of the Resident Nonimmigrant Population in the United States. Population Estimates, 2008. DHS Office of Immigration Statistics. 2010. [Web. September 25,].

BBC News, Thousands in UK Citizenship Queue. 2006. [Web. September 23, 2010].

Canadian Department of Justice. Employment Equity Act. Ottawa; 1995. [Web. September 15, 2010.].

Locker, Kitty, Findley, Isobel. Business Communication Now. Canada: McGraw Hill Ryerson; 2009. [Print.].

Office for National Statistics, United Kingdom Government. News Release: Reversal of North to South Population Flow Since the Start of the New Century. 2005. [London, Web. September 20, 2010].

Office for National Statistics, United Kingdon Government. 2011 Census. Ethnic Group, National Identity, Religion and Language Consultation: Summary Report on Responses to the 2011 Census Stakeholders Consultation 2006/07. 2007. [London, Web. September 2010.].

Perreault, Samuel, Visible Minorities and Victimization. Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics Profile Series, 2004. [Web. September 15, 2010.].

Riggs, Donald E. Academic Library Leadership: Observations and Questions. College & Research Libraries. 1999; 60(1):6–8.

Siddiqui, Haroon, Why Hugging an Immigrant is a Good Idea. Issues Facing Our City Region. Toronto City Summit Alliance, 2005. [Web. September 23, 2010.].

Statistics Canada, Minister of IndustryEthnic Diversity Survey: Portrait of a Multicultural Society. Ottawa, 2003. [Web. September 15, 2010.].

Statistics Canada, Study: Canada’s Visible Minority Population in 2017. 2005. [Web. September 25, 2010.].

Statistics Canada. Canada’s Ethnocultural Mosaic, 2006 Census: National Picture. Ottawa; 2010. [Web. October 6, 2010.].

Tien, Chang-Lin, Challenges and Opportunities for Leaders of Color Eds.Valverde Leonard A., Castnell Louis A., eds. The Multicultural Campus: Strategies for Transforming Higher Education. CA: Altamira Press, 1998.

Weiner, Sharon G. Leadership of Academic Libraries: A Literature Review. Education Libraries. 2003; 26(2):5–18. [Print].