Managers and leaders

Abstract:

Management and leadership are two different concepts. They are sometimes used interchangeably. Not all managers are leaders and not all leaders have management skills. Managers are not expected to be visionaries whereas leaders generally are. Managers forecast future implications based on evidence, whereas leaders have a vision and will lead their organization towards it. Some people are natural leaders and others need a lot of encouragement and motivation. Motivation is a key factor in preparing future leaders and a skill that is common to both managers and leaders. Without motivation, there can be no leaders or managers.

Who are leaders?

On the first day of a leadership workshop offered through the University of Saskatchewan, the instructor wrote on the board “leadership is …” and asked participants to fill in the rest. Each of the 27 participants had their own interpretation of leadership. There are no agreed-upon definitions of leadership or leaders. The concept of leadership differs based on many things, and it can be domestic, global, gender based, and culture based. Every culture has its own idea of and ideals for leaders. In Latin America, leadership is masculine, authoritative, and aggressive. In the US, leadership focuses on the bottom-line, and in Japan, leadership is for the wise and elderly. In other words, it is for those with many years of experience, not for those who climb the organizational ladder quickly. While an educational degree such as an MBA is important for leadership in countries such as the US and Germany, it is not so vital in many countries of Africa. Age does not factor in the US, the UK, Germany, France, and Poland when leadership is considered, but it is very important in Japan, Vietnam, and China. In Asia, it is generally believed that the older one is, the wiser they are. In Germany, the Netherlands, the US and Israel, it is not important for a leader to be from an elite background, but it matters in Latin America, France, the UK, Poland, Japan, China, Africa, and Vietnam (Derr et al., 2002: 289–293). Leadership is personal but should also work for the organization. Within the domestic confines of a country, leadership is further defined by the organization. And within the organization it is further defined by individual styles and traits. The American idea of leadership does not hold true in other countries. Leadership, from available definitions in American literature of the 20th century, can be summed up as rational, management oriented, male, technocratic, quantitative, cost-driven, hierarchical, short term, pragmatic, and materialist.

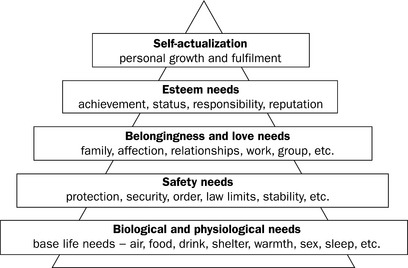

Figure 2.1 Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Source: Maslow’s Hierachy Chart redesigned by Alan Chapman at businessball. com – used with permission

Table 2.1

| Managers | Leaders |

| Position in the organization | Leadership is a role and can come from anywhere in the organization |

| Desk oriented, evidence based | People focused and people oriented |

| Internal focus | External environment focus |

| Controlling | Motivating and influencing |

| Implement goals and directions | Establish goals and directions |

| Administrative | Non-administrative |

| Supervisor | Coach who may teach, but not supervise closely |

| Organize | Align |

| Drive | Persuade |

Alder (1999: 240) cites the Anglo-Saxon origins of the verb to lead as laedere, which translates to “people on a journey,” and the Latin origin of the verb agere, which means “set into motion.” In the contemporary world, a leader is seen as a visionary who creates change and helps the organization and its people go on this journey of change. It is about influencing others to agree on a societal or organizational change. Leaders should make decisions and accept responsibility even when the decision does not reap intended benefits. Leaders should follow the ethical and moral codes of society and the organization. It is agreed that leaders exhibit certain skills and traits. These skills seem to change based on the leader, his/her background, and the situation in which the leader works. Leadership research indicates “that certain personal traits and characteristics are especially important for leaders and for the exercise of leadership” (Mason and Wetherbee, 2004: 188) but the exact nature of those skills remains unspecified. There are over 200 different traits and skills identified by different authors on their research on leadership.

Who are managers?

Management on the other hand has agreed-upon definitions. One such definition is: “it is the process of planning, organizing, leading and controlling an enterprise’s financial, physical, human and information resources to achieve the organizational goals of supplying various products and services” (Griffin et al., 2010: 189). Since management is specific to organizations, various books offer variations of this definition. But it is generally agreed upon that managers help in planning, organizing, leading, and controlling. Unless they themselves have leadership skills, managers cannot lead without the help of a leader.

The origin of managers or management

J. B. Say, a French economist, coined the word entrepreneur. He defined the entrepreneur as a person “who directs resources from less productive to more productive investments and who thereby creates wealth” (Drucker and Maciariello: 13). This is not far from any definition of today’s manager. One cannot be productive and create wealth without controlling, organizing, motivating, and leading by doing. Say’s followers, Francois Fourier and Comte de Saint-Simon, “discovered” management in the early 19th century, before it actually came into existence. They could see the emergence of organizations and a need for a person to manage them. Prior to this, the idea of an organization did not exist. It was believed that the economy, not humans, was the driving force that dealt with the behavior of commodities. Humans were only expected to adapt. Hence, no concept of organizations and no management. With a systematic blueprint for economic development came the systematic development of management – an area that would focus on managerial tasks – and the tasks of finding ways to improve productivity and relationships among workers and between workers and their superiors. According to Drucker and Maciariello, the management boom happened after the First World War. It was the events that occurred during this war and the handling of it that conceived the idea that “management” could restore the economy. But, with so much destruction all around and the economy down on its knees, there wasn’t much will to restore the economy and the first boom of management died here. After the Second World War, sometime during the twentieth century with the economy slowly recovering, Western and European societies “became a society of organizations” by creating various tasks towards restoring the economy and dividing the responsibilities. Whether big or small, these organizations needed management. Management was developed, studied, and practiced as a discipline. Formal and informal organizational structures, business objectives, strategic planning, decision-making processes, business communication models, and marketing processes were all developed and studied during this time. Now, in the era of the global economy and virtual organizations, the study of management still continues to evolve today.

The evolvement of management

After the Second World War, the management of businesses moved from the idea of “ownership” to organizations. As the economy moved to an industrialized and organizational format, management came to be motivated by the needs of the organization and its people. This meant finding ways to increase productivity and profit and dealing with laborers. Before organizations were formed, there were no management positions, just “charge hands” enforcing discipline over fellow peasants (ibid.: 18). With the emergence of management and organizations, production increased and this led to the stabilization of the economy. With a stable economy emerged a developed world. A lack of management and a lack of organizations which divided work into groups and completed them successfully would have meant chaos for the continents that had just come out of two wars. It was management that created the “social and economic fabric of the world’s developed countries. It has created a global economy and set new rules for countries that would participate in that economy as equals” (ibid.). While the first world was developing rapidly, countries in Asia were still trying to achieve independence from their oppressors and from there on took many decades to stabilize their own economy, and some of them are still trying to do so. Countries such as India were not open to foreign markets until the mid-1990s, and the idea of organizations and management as it was well established in the West did not exist there until very recently. Management in countries like India was considered oppressive, demanding, and something to obey and perform. So, as these countries develop, their managers, like those in the West a century or so ago, are learning to deal with educated workers. They can learn from the models established by Western or European countries.

In North America, the UK, the US, Australia, and other countries that are open to immigrants, management is undergoing another change. Just as in leadership, the focus of management in various organizations in these countries is now shifting to managing people of different cultures – people that are fundamentally different in their thinking, behavior, languages, customs, traditions, clothing styles, and economic, educational, and religious backgrounds. More challenges are brought about by the fact that these multicultural populations are sometimes not even full-time employees of the organization. They could be contract workers or outsourced employees working a world away from their leaders and managers. In the virtual, multicultural world of work, the functions of managers and leaders continue to be challenged.

These same challenges are being faced by libraries in these countries as well. There are many more library staff and librarians from multicultural populations working in these countries in the 21st century than there were in the previous century, and this is evident from the number of articles and books that are written and published on this topic. There is little material on leadership from minority librarians, but there is some on the hiring and retention of minority librarians in academic libraries.

Are there differences between managers and leaders?

Apart from different definitions, traditionally speaking, there are many differences between managers and leaders.

Management is a position, a function. Leadership does not always have to be a position or title. It is possible that to be considered a leader of an organization (in title, such as a Dean or a Director of a library) one has to climb up the rungs of management. But having a leadership title alone does not make one a good leader. In a library setting, leaders can be anyone from the circulation supervisor, librarians, managers, Dean of the library, to library staff.

Management is generally a mid-or upper-level position in an organization’s hierarchy. While leaders themselves are at higher-level positions, leadership itself can come from any position within an organization. A page at a library may have a better vision on how and where to shelve items so that they are better accessible and visible. A manager might be a better judge of how this redesigning of the shelving process should take place. This page is not a leader with a title, but in a small way contributes to the success of his/her organization. This is what a leader does, perhaps on a bigger scale for the whole organization. In the article “The Crisis and Opportunities in Library Leadership,” Riggs (2001: 6) differentiates leaders and managers thus:

Library managers tend to work within defined bounds of known quantities, using well-established techniques to accomplish predetermined ends; the manager tends to stress means and neglect ends. On the other hand, the library leader’s task is to hold, before all persons connected with the library, some vision of what its mission is and how it can be reached effectively. Like managers, there are leaders throughout the library. The head librarian is not the only leader in a library. This fact must be remembered and addressed during leadership development programs.

Managers find and work with evidence – the finance, human resources, productivity, and profit and loss of an organization are taken into account when a manager makes a decision. Leaders are expected to think outside the box and make decisions that may challenge this evidence. Leaders might have to make radical changes and decisions whereas a manager might just follow instructions from a higher rung of the hierarchy. There are always exceptions and occasions in organizations where a manager might make radical changes, but this is not the norm.

Management is desk-bound. Although this idea could be challenged in the virtual environment, management focuses on drawing out plans and executing them, which is still desk-bound work. Leaders do not focus on desk work. They focus on reaching out – reaching out to other organizations, to people in the organization, and to other external environments that would maintain the stability of their own organization.

Management is about specifics and productivity. Leadership is about the betterment of the organization as a whole on various levels both at present and in the future, without worrying about specifics. Leaders leave specifics to managers.

Management is administrative. Leadership goes beyond administration. It is about walking the territory, building a network, and knowing powerful people to get the job done.

Management is about recording information. It is up to managers to do job evaluations, maintain expenses, etc. Leadership is about seeking and forming new relationships. Or, as Kouzes and Posner (2007) put it, “leadership is relationship.” It is a “relationship between those who lead and those who choose to follow” (ibid.: 24). To have followers continue to follow them, leaders initiate new ideas and challenge the old ways.

Management concerns itself with the efficient use of resources. Leadership, while concerned about the efficient use of resources, focuses on finding new sources of resources.

Leadership focuses on the environments outside – those that can affect the organization, those that should be in alignment with the organization, and those that should be avoided and alienated. Managers focus on the internal operations of an organization.

Managers follow protocols and organizational policies. By adhering to rules, they do the right things. Leaders will take the organization to different levels by breaking these protocols and making policy changes. Managers might question or challenge the feasibility of “change” at various levels of the organization, and leaders would like you to believe in the slogan “yes we can” and work towards it. Leaders will need these questioning managers to create and record policy changes and provide a strong structural foundation by having all the written documents in place for the organization.

Managers, by nature of their positions, tend to control. They might be responsible for the finances, production, and human resources of an organization. They cannot do their jobs effectively if they don’t find ways to control loss of monies and staff turnover within the organization. Leaders on the other hand like to hear and try out new ideas and encourage others to change and to adapt to change.

Management is more task-focused and leadership is more people-focused. This is not to say that managers don’t focus on people and leaders don’t focus on tasks. It is important to remember that managers should have human resources skills and leaders need to accomplish tasks.

Managers predict change based on the evidence they have collected. Leaders bring about change.

Managers focus on organizing and staffing. Leaders work on aligning staff to work together towards a common goal.

Leaders establish goals and directions. Managers establish ways to achieve those goals and directions.

Managers are engaged in day-to-day problem solving and leaders are focused on energizing and motivating colleagues, subordinates, and external collaborators.

Managers accomplish and achieve by “driving” their workforce, and leaders do the same through persuasion and influence. But again, whether a leader or manager “drives” or persuades varies, based on the culture of the organization and the style of the leader.

In a library environment, as in many other organizational environments today, leadership and management are no longer solely dependent on one person. One person alone is not expected to have a vision, lead through and implement changes. As Porter-O’Grady puts it, “in today’s socio-technical organizations, [organizational] culture is collective (‘team’), the expectation is involvement and investment, and the style of implementation is facilitative and integrative. Both staff and management now know that no one person has the only ‘best’ strategy, vision or methodology for change” (Porter-O’Grady, 1993: 53–54).

In this team environment, managers and leaders are agents of change who depend on the ability and skills of collaborative staff to help provide direction for the organization. For example, the Dean of the academic library may not always have decision-making power but may depend on the collegium’s guidance. A Director of a public library may seek advice from the Board. Leaders should see themselves as part of the team or groups of teams within the organization who produce results through joint efforts.

As Clutterbuck and Hirst (2002) mention in their paper, “Leadership Communication: A Status Report,” researchers like Warren Bennis, who have tried to distinguish between managers and leaders, have been badly misunderstood. This is not because Warren Bennis’s distinguishing factors were inaccurate, but because they struck a strong chord of realism. Some of the distinguishing factors mentioned by Bennis were:

![]() The manager focuses on systems and structure; the leader focuses on people.

The manager focuses on systems and structure; the leader focuses on people.

![]() The manager imitates; the leader innovates.

The manager imitates; the leader innovates.

![]() The manager accepts the status quo; the leader challenges it.

The manager accepts the status quo; the leader challenges it.

![]() The manager’s eye is on the bottom-line; the leader’s eye is on the horizon.

The manager’s eye is on the bottom-line; the leader’s eye is on the horizon.

![]() The manager does things right; the leader does the right thing.

The manager does things right; the leader does the right thing.

In today’s organizations it is very true that both management and leadership are intertwined. Both managers and leaders manage and lead, and depend on each other’s skills to succeed.

Commonalities

Both management and leadership can be taught and learned. Managers can also be leaders and leaders can possess management abilities. From a study conducted by Henry Mintzberg et al. (1998: 4–8) it was concluded that managers do the following:

![]() Managers work at an unrelenting pace (ibid.: 4).

Managers work at an unrelenting pace (ibid.: 4).

![]() Managerial activities are characterized by brevity, variety, and fragmentation (ibid.).

Managerial activities are characterized by brevity, variety, and fragmentation (ibid.).

![]() Managers have a preference for “live” action and emphasize work activities that are current, specific, and well defined (ibid.: 6).

Managers have a preference for “live” action and emphasize work activities that are current, specific, and well defined (ibid.: 6).

If these are accepted as day-to-day managerial duties, then all of these can be applied to leaders as well. Leaders also work at an unrelenting pace and collaborate with their team. Leaders’ activities can be characterized by both brevity and in some cases longevity, and leaders like action.

Managers can be at various levels of the organization: top-level managers, mid-level managers, and first line managers. As previously mentioned, leadership can come from any level of the organization.

Managers are expected to posses certain skills and some of these can also be transferred to leaders: human relations skills, time-management skills, decision-making skills, and conceptual skills (Griffin et al., 2010: 187). Both leadership and management are important for an organization. Leaders create and direct change, while managers create a structure to implement this change in an orderly process. Leaders can keep the organization current, abreast, and aligned with its external environments. Managers maintain stability and coordinate activities at all levels of the organization, internally.

Managers have to “control” due to the nature of the work. There are leaders who control with their authoritative style of leadership. This style of leadership may work for very few organizations – it is certainly not a style for modern-day libraries.

Leaders motivate. Managers also motivate their staff, by allowing them the freedom to experiment and learn by doing. Through motivation, both managers and leaders enable others to act, be productive, and attain a set of organizational goals.

Both leadership and management are art and science. There is a huge body of literature covering both topics where arguments were put forth, analyses made, evidence presented with scientific precision. It is not leadership qualities that are science, but the study of it, and the wealth of literature available on the subject (not necessarily all in the library world) brings it closer to being science. Some would disagree. Mullins and Linehan (2005: 134) state that “the taxonomy of leadership qualities and behaviours cannot be rigorous, as leadership is not a rigorous scientific phenomenon.”

Some writers see leadership as an art (Heifetz and Linsky, 2002; Scholes, 1998) because leaders don’t always conform to stereotypical behavior but tend to be inventive, creative, and original. Both managers and leaders have to be dynamic, adaptive to changes, and be able to empower others to complete tasks. Empowering others is an art that cannot always be taught in a classroom. Managers and leaders coach others and, again, coaching is both an art and a science.

Some leadership authors call leadership “organic.” Schreiber and Shannon (2001: 40) call leadership “a discovery process.” Since leaders “need to cultivate a welcoming attitude to leadership problems” (ibid.) by learning from every situation and experience, they see leadership as an evolving organism. As Karp and Murdock (1998: 256) put it, “the quality of leadership is born in an individual’s inherent personality and then refined by that individual’s life experiences, behavioral choices, attitudinal proclivities, and core values,” by which they suggest that leadership is elusive.

Both leaders and mangers are expected to have critical thinking skills, analytical skills, to be efficient coaches, and to be familiar with problem-solving techniques. They should have technical skills, conceptual skills, and human resources skills, although, depending on their position, a combination of some of these skills might be more useful than others. A manager at a lower level might have good technical skills, but a leader at a higher level might be more adept at human resources skills and conceptual skills than technical knowledge.

Both leaders and managers have to work hard to develop trust. As Clutterbuck and Hirst (2002) say, leaders and managers have remarkable resilience. By this, the authors mean that both leaders and managers admit their mistakes when things go wrong, learn their lessons, and incorporate these lessons into their vision. They don’t wallow in self-misery.

Both managers and leaders should be aware and self-aware. They must be aware of their actions and the consequences, aware of their mistakes, and be aware of newcomers to the organization, their expectations and experiences. They must be respectful of staff from different cultural backgrounds, be open-minded, be willing to learn, be challenged, and be adaptable.

Both managers and leaders work towards the success of their organizations.

Last but not least, managers do lead people to work towards the organization’s goal. And the very best leaders are first and foremost effective managers.

Libraries and their leaders and managers

Library leaders and managers possess the qualities mentioned above. Ethnic-minority librarians who come from various backgrounds should be aware of the differences between management and leadership and how things are perceived differently in their new country in comparison to their home country. It is important to realize one’s potential and to have the ability to fit into either management or leadership roles. If being a controlling leader is the style one possesses, this style may not work in today’s organizational structures of the Western world which are looking forward to globalization and to working without borders. It certainly will not work for modern-day libraries which continue to be growing organisms, as first identified by S. R. Ranganathan (Leiter, 2003: 417–418), incorporating changes to their structure, their collections, and their relationships with external organizations. If the ability to control, to make decisions based solely on evidence, and to create a schedule for reaching goals are a person’s strong skills, then it is important for that person to accept that they may be better suited to a management position. If one is interested in being a leader, then one has to work towards acquiring the skills and traits that are expected of a leader. It is time to let go of the old ways and adapt to the new ways of life in their new home.

Library authorities should be able to recognize potential leaders and managers from various immigrant groups. This should be done regardless of the previous experiences and qualifications these individuals might have acquired in their home countries. A lack of knowledge of local idioms, cultural implications, or accent issues with language should not deter higher-level library authorities from encouraging minorities in trying to become leaders or managers. Winston (2001) speaks of recruitment theory and of ways of identifying successful leaders in the library profession. He goes on to say that many issues come into play when a person is choosing their profession – not least the role and influence of teachers, counsellors, role models and friends – and the reasons for choosing a profession play a role in later leadership interests within the profession. Winston admits, however, that when it comes to ethnic minorities, it is not clear what career decision process is involved. His research focused on business, science, and engineering librarians in academic libraries (colleges and universities), and children’s librarians in public libraries, and the results for academic librarians suggest that “those who did not intend to become academic business librarians, as characterized by the factors that affected their choice of a professional specialty, are somewhat less involved in leadership activities” (ibid.: 27). In many ethnic cultures the push is to follow subjects or fields that will prove lucrative for the student – medicine, engineering, dentistry, etc. If this is true of any of the minority cultures, then many of the ethnic-minority librarians in the UK, the US, Canada, and Australia are accidental librarians who may need motivating to become involved in leadership activities. One also has to remember that some of the ethnic-minority cultures do not have well-established libraries for the library profession to be considered as a career option. McCook and Geist (1993) speak of the library profession as being invisible to potential minority applicants for a number of reasons. For example, a lack of early monetary incentives such as scholarships and tuition waivers; a lack of partnerships with minority groups; and a failure to reach out to minority recruits early enough in their education process. They conclude that “diversity is being deferred by the library profession,” and the Association for Library and Information Science Education data proves “that the library profession has done little in the way of recruiting minorities.” While there are many library associations dedicated to minority librarians (who are already librarians), the library profession has a long way to go in proactively seeking and recruiting minority librarians. McCook and Geist are more concerned about providing multicultural services when they speak of a lack of minority librarians; the same concern can be extended to leadership issues as well. From all the literature available, there seems to be no strategy in place for actively attracting or recruiting ethnic-minority librarians to the profession.

Motivating ethnic minorities

A sense of belonging is the most important factor for immigrants with regard to their potential for leadership initiatives. The feeling of “belonging” comes when they feel secure and settled. At some later point in their career comes the leadership initiative. As Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs model indicates, wanting to fit in, and therefore learning local culture, comes under social needs and is only the third level of needs. Although Maslow was not referring to immigrants in particular, his needs model applies to immigrants as well. Based on his model, immigrants’ first needs are physiological – the need for survival, the need for food, clothing, and shelter. The second rung on the ladder is the need for security – the need for a job that provides present and future security. The third level is social need, which is the need for companionship.

This is the stage at which immigrants will try to mingle with society at large and feel the need to learn, or at least show some interest in learning, local culture. This is when a sense of wanting to “belong” arrives. The next level up is esteem needs – a need for status, recognition, and self-respect. Once immigrants find their place in the culture and learn the nuances of their new culture and have a sense of belonging, their esteem needs are satisfied. The final need is the self-actualization need – a need for self-fulfilment. It is at this level of need that one’s leadership abilities can be tested. It is at this level that individuals like to develop their capabilities and skills in order to challenge themselves. Of course, what each individual considers challenging will be different. For some, learning to drive in their new country by adhering to traffic rules might be the challenge one looks forward to at this level. Others might look forward to more complex challenges such as leading the organization that they have been working for. But all immigrants, like everyone else, need motivation to seek self-actualization needs.

Leaders and motivation

One of the skills leaders should possess is motivation; they should be both self-motivated and have the ability to motivate others. Leaders have been identified as people who are motivated by the need for power, for domination, for achievement, and for responsibility (Zaccaro et al., 2004: 113–115). Anyone in a leadership position who has no motivation is impotent as a leader and unproductive within the organization. A good leader not only motivates others to do their jobs efficiently but also motivates others to take the lead. Motivation in leadership should not be about career goals, but about enabling and encouraging others to perform towards the success of the organization. This is where leaders can be coaches and nurture leadership skills in others in the organization.

What is motivation and how does one motivate others?

Griffin et al. (2010: 308) define motivation as “the set of forces that cause, focus, and sustain workers’ behaviour.” Kouzes and Posner (2007) mention two kinds of motivation – intrinsic and extrinsic. They go on to explain these by saying that “people do things either because of external controls – the possibility of a tangible reward if they succeed or punishment if they don’t – or because of an internal desire” (ibid.: 115).

Lack of motivation in a person’s personal life means not wanting to seek any of the needs indicated by Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs model. Lack of motivation at work means stagnation: stagnation in a position, in productivity, being stuck in a rut. If employees are not motivated, both intrinsically and extrinsically, they are not going to seek out new ways of doing their work effectively. Motivation is not just about “carrot and stick” but about encouraging the heart. Encouraging the heart can maximize an employee’s full potential and empower them. It should be followed by both the financial and moral support of the organization. It is not very effective to encourage employees to find new ways of doing a job and then not support them to pursue these new ways. Staff must be given clear direction and the best opportunities possible to do what they do best. This can only be done through ongoing dialogue and by keeping all communication channels open between leaders, managers, and employees. In the library world, new ways of doing a job could mean researching and buying collections in newer formats or introducing new technology for staff – Blu-ray Discs, mobile technology, wireless technology, e-books and journals, digitization, and, more recently, iPads. Motivation is about allowing more democracy, building a supportive work environment, recognizing staff accomplishments, and having less bureaucracy. A democratic work environment is one that offers attainable goals and allows the freedom to challenge. If bureaucracy provides an unattainable goal, or offers too many restrictions, this is as good as not having any motivation at all and in the worst case scenario it could lead to workplace antagonism and defiance.

Team motivation

In libraries, librarians and staff quite often work in collective groups or team environments. Katzenbach and Smith (2005) distinguish groups and teams as two different concepts. They identify a group environment as a place where there is individual accountability, a strong leader, and where the focus is on individual work products. A team on the other hand has individual and mutual accountability, with each individual taking leadership roles, and offering collective work products. An effective team has members whose skills complement each other and who produce a desired result as “one.” Katzenbach and Smith (ibid.: 165) define a team as “a small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, a set of performance goals, and approach for which they hold themselves mutually accountable.” Ilgen et al. (1993: 247) describe a team as having collective goals or objectives that exist for a task-oriented purpose. Many libraries have departments or project-based groups that function as teams and in such groups there is a leader that participates, engages, and offers directions and suggestions for efficient team performance. It was Parker (1991) who identified the fundamental element of teamwork, the team players and their styles. He identified four distinct styles of team players: the contributor; the collaborator; the communicator; and the challenger. A contributor is task-oriented and dependable for date provision; a collaborator is goal-directed, with a vision, and has the “big-picture” in mind; communicators are process-oriented people persons; and challengers questions the goals, methods, and ethics of the team (ibid.: 63–64). A good team needs members with all these qualities so that there is a balance in the project results. Parker identifies an effective team as one that is informal, comfortable, relaxed, participative, has good listeners, is goal oriented, is open to criticism, and is self-conscious of its own operations (ibid: 21).

Teams are made up of individuals who strive to deliver as one, and this is not an easy task. It takes time for these individuals to work as one. Teams go through four stages in the life of their task-group: orientation, formation, coordination, and formalization. Orientation is when team members get to know each other and the task at hand. Formation is when the conflict begins as teams have suggestions and opinions and try to define the problem. The next phase is coordination, the longest phase where the team focuses on the task. This is also the phase where a team needs focus and direction, and a good leader can offer both. In the last phase of formalization, the group seeks consensus on their accomplished task (Locker and Findley, 2009: 127). This is based on Tuckman and Jensen’s five critical stages of successful team building: forming, storming, norming, performing, and adjourning. Forming is the orientation phase. Storming is where ideas are exchanged and conflicts arise. Norming is the stage where team identity is developed and team ground rules and values are laid. Performing is the important stage where the team has gone beyond conflict and has learnt to work efficiently. The final stage, adjourning, is where the team has completed its set task.

Team members should be aware of their strengths and weaknesses. As Parker (1991: 150) says, “develop a plan to optimize your strengths and minimize your shortcomings” and this will help in being an effective team member.

Teamwork has a wholesome effect, where more than one individual’s thoughts, ideas, and perspective come into action. This wholesome effect in itself gives credibility to the work produced by a team.

Though some research differentiates between teams and groups, it is often misinterpreted in libraries. The word “team” is used very loosely in a library environment. Such a team could be a committee or subcommittee established to accomplish a task, provide input, offer recommendations, etc., and has someone who acts as a facilitator for the team – to set deadlines, accomplish tasks, and deliver results on time. Such teamwork (in the loosest sense of the term) in libraries should not only focus on immediate supervisors but should involve the top leaders of the organization such as the director or dean of the library. This leader has to motivate teams as they work on various projects and face challenges in the course of their work.

Team motivation is not very different from individual motivation. A team can consist of members from different age groups and different cultures with different understandings and ideas about how to work on the project. A leader needs to identify these differences and work with the idea of “self-interest” of individual members of the team. A leader should also know how to identify and work with the weakest link in the team. The weak link might either need specific directions, or extra motivation, or might need to be retired from the team. Keeping communication lines open among team members and between the team and the leader – with the leader keeping a check on the morale of the team, offering timely, positive feedback, offering constructive criticism where necessary, and developing a sense of accountability in the group – will make teams successful and productive and leave individual members with a sense of achievement and satisfaction.

There are various theories on motivation and two major approaches to motivation in the workplace are discussed here.

Classical theory

The classical theory of motivation states that employees are motivated solely by money (Griffin et al., 2010: 308–309). While this may be true in some cases or to some extent within a job, there comes a time when employees realize they are not functioning at their full capacity to be efficient workers. Many libraries that have trouble hiring due to various factors, such as geography, organizational issues, climatic conditions, use this theory to hire and retain workers. Many librarians will take these positions as their first jobs, but if there are no other motivational factors to retain them, offering the job satisfaction they are looking for, they will move away to greener grass. Whether they will be happy in their new jobs may be questionable, but the institution that originally hired them will be impacted by turnover rates and time and money spent in finding, hiring, and training new librarians.

Early behavioral theory

Early behavioral theory examines the relationship between changes in the physical environment and worker output by using the Hawthorne effect (ibid.: 309–310). Harvard researchers studied the variations in productivity of Hawthorne workers at the Western Electric Company by increasing lighting levels for workers. When lighting was increased, productivity increased. Researchers concluded that workers responded better to the attention they were receiving from management. This has been disputed subsequently. Later research suggested that workers work better when they participate in an experiment and that there are other variables to consider in this experiment. It also said “that output fell when the trials ceased, suggesting that the act of experimentation caused increased productivity” (The Economist, 2009). The working environment is very important for all workers in all organizations.

Libraries were traditionally cold places with lots of books and quiet spaces to study. Today’s library users and in fact library staff would prefer not to use or work in old-fashioned libraries. They would like a coffee place, a space to socialize, space to work with their laptops and iPads, workrooms to gather in groups and work on a project, study areas, etc. Contemporary library users see a library as a place to gather, collaborate, and socialize. There have been suggestions that while “the future library will need to continue to provide a central, local place for digital objects, the future library will also want to continue to provide a central, local space for reader-users” (Atkinson, 2001: 8). With close to 50 per cent or more of collections available online and many programs available through distance learning (ibid.), in many libraries library administrators are able to provide the much-needed space to users. Leaders in libraries recognized this need and acted on it. Other libraries followed suit. Library staff need updated technology and continued support to be able to use this technology in order to provide access to their collections, to teach patrons and students, to archive information, and to keep themselves abreast of research happening in the library environment. Users demand immediate online help as they are working on a project and librarians are trying to meet this demand by offering help via live chat services and also through phone and email services.

Immigrants coming from a developing or an underdeveloped country who have worked in a library in their own country could find this set up very different from the libraries they are used to. They might come from traditional libraries that are not user-friendly but exist to maintain and protect existing collections. They might be used to a traditional desk, to silencing users on library premises, they may not have used the most current technology, and they may be unaware of inter-library loan procedures as they exist in Western cultures. Not many librarians are completely unaware of newer library models and their services, but this is something to keep in mind when hiring immigrant librarians. They might need more time to learn their immediate environment and the services available to patrons. They “need to be reassured about what they are doing right” (Kumaran and Salt, 2010: 13) and given the opportunities and encouragement to learn.

After the Hawthorne experiment, other related models such as the human resources model, motivation-hygiene theory, and Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs model (discussed previously) came into existence, all related to human needs and the fulfilment of them as a motivation factor. The human resources model states that managers fall into two categories: theory X managers who believe that people are naturally lazy and need to be punished or rewarded; and theory Y managers who believe that people are naturally active, productive, and self-motivated. Theory X managers tend to be more authoritative with an emphasis on control and a focus on the direct supervision of employees, and theory Y managers should be careful not to be taken advantage of by those who might be lazy. A tendency to lean towards being a theory X or theory Y manager (or leader) could be cultural (Griffin et al., 2010: 310). As Den Hartog and Dickson observe, there are cultures where people are believed to be lazy, evil, and who therefore earn distrust. In their words, “distrust prevails in cultures where people are believed to be evil, and as such more monitoring and closer supervision of employees can be expected” (Den Hartog and Dickson, 2004: 262).

Motivation-hygiene theory believes that hygiene factors, which include working conditions, pay, interpersonal relations, and motivational factors such as recognition and the potential for advancement, are all important (Griffin et al., 2010: 311).

Contemporary motivation theories

Two well-known contemporary motivation theories are equity theory and expectancy theory (ibid.: 311–313). The former suggests that people compare their contribution to their job and their position to that of others (who are in a similar position) and expect rewards accordingly. Immigrants move to new countries for a better life, and a better life means earning more money sooner or later. They are not going to find satisfaction in a job that pays the minimum wage or comparatively low wages, at least not for too long, especially if they are educated and are able to pursue some education and upgrade their credentials in their new locality. Many of the immigrants who came to the US for IT-related positions switched jobs frequently simply for more money. The library industry is not as competitive as IT industries once were and probably never will be. But if retention becomes an issue for libraries this is something to be aware of. Of course, not all libraries can afford to pay more – public libraries and some special libraries may be entirely dependent on public taxes or funding and many academic libraries may not get all the grants they were promised. Though promising higher salaries to their librarians may not be an option, it is important for library administrators to review salaries at set intervals to make sure they are offering competitive wages. Another issue in libraries is advancement by seniority. Newly hired librarians and library staff who have very little experience are energetic, enthusiastic, and creative with what they can do within the boundaries of their job. If they are not considered for better positions because of lack of seniority within the organization, there is no motivation factor for these librarians. If these new librarians or staff happen to be desperate immigrants, they might consider doing this job only until they can find a better one.

Expectancy theory says that people are only motivated to work towards rewards they want and that are attainable. If a new librarian has to work for twenty years within a library before getting four weeks’ vacation, this is not a huge motivational factor. Regardless of how hard they might work, they are not going to advance much in their career because of institutional regulations such as seniority-based approval and advancement.

Motivation can be accomplished simply by trusting others to do their jobs, by showing appreciation, by recognizing their accomplishments, by reinforcing positive performance behavior, by matching expectations to people’s skills, by setting attainable goals, by providing timely, constructive feedback, by providing a clear sense of direction, and by setting standards. Motivation is not about setting low expectations, but about setting expectations that are achievable and attainable, and about providing the right means to reach that goal. Good leadership that can influence with motivation will naturally lead to the success of an organization and the success of its employees, and this in turn will lead to the success of a leader.

There are many commonalities between leaders and managers in all organizations. In libraries, when a manager has leadership qualities and leader-managerial skills they become an asset to their organization. Both managers and leaders should enable their library employees by motivating them to be leaders – to contribute collaboratively and individually to the success of the organization.

References

Alder, Nancy. Global Leaders: Women of Influence. In: Powel Gary N., ed. Handbook of Gender and Work. London: Sage Publications; 1999:239–262. [Print.].

Atkinson, Ross. Contingency and Contradiction: The Place of the Library at the Dawn of the New Millennium. The Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 2001; 52(1):3–11.

Bolman, Lee G., Deal, Terrence E. Leading with Soul. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1995. [Print.].

Clutterbuck, David, Hirst, Sheila. Leadership Communication: A Status Report. Journal of Communication Management. 2002; 6(4):351–354.

Den Hartog, Deanne N., Dickson, Markus W. Leadership and Culture. In: Antonakis John, Cianciolo Anna T., Sternberg Robert J., eds. Nature of Leadership. London: Sage Publications; 2004:249–278. [Print].

Derr, C. Brooklyn, Roussillon, Sylvie, Bournois, Frank. Cross-Cultural Approaches to Leadership Development. Westport: Quorum Books; 2002. [Print.].

Drucker, Peter F., Maciariello, Joseph A.Management. Harper Collins, 2008. [Print.].

The Economist. Questioning the Hawthorn Effect, 2010. [June 4, 2009. Web. October 18].

Griffin, Ricky W., Ebert, Ronald J., Starke, Frederick A., Lang, Melanie D.Business. Toronto: Pearson Canada, 2010. [Print.].

Heifetz, Ronald A., Linsky, Marty. A Survival Guide for Leaders. Harvard Business Review. 2002; 80(6):65–74.

Ilgen, Daniel R., Major, Debra A., Hollenbeck, John R., Sego, Douglas J. Team Research in the 1990s in Leadership Theory and Research: Perspectives and Directions. In: Martin M., ed. Chemers and Roya Ayman. San Diego: Academic Press, Inc; 1993:245–266.

Karp, Rashelle S. and Cindy Murdock. “Leadership in Librarianship.” Leadership and Academic Librarians. Eds. Terence F. Mech and Gerard B. McCabe. Westport: Greenwood Press. 251–264. Print.

Katzenbach, Jon R., Smith, Douglas K., The Discipline of Teams. Harvard Business Review, 2005:162–171. [July-August].

Kouzes, James M., Posner, Barry Z. The Leadership Challenge, 4th ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2007. [Print.].

Kumaran, Maha, Salt, Lorraine. Diverse Populations in Saskatchewan: The Challenges of Reaching Them. Partnership: the Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research. 5.1, 2010. [Web. September 19].

Leiter, Richard A. Reflections on Ranganathan’s Five Laws. Law Library Journal. 2003; 95(3):411–418.

Locker, Kitty O., Findley, Isobel M. Business Communication Now. McGraw-Hill Ryerson: Canadian edition; 2009.

Mason, Florence M., Wetherbee, Louella V. Learning to Lead: An Analysis of Current Training Programs for Library Leadership. Library Trends. 2004; 53(1):187–217.

McCook, Kathleen de al Pena, Geist, Paula. Diversity Deferred: Where Are The Minority Librarians. Library Journal. 118.18, 1993. [18].

Mintzberg, Henry, Kotter, John P., Zale Znik, Abraham. Harvard Business Review On Leadership. Boston: Harvard Business Press, 1998; 4–8. [Print.].

Mullins, John, Linehan, Margaret. Desired Qualities of Public Library Leaders. Leadership and Organization Development Journal. 2005; 27(2):133–143.

Nuvvo Transcript of Obama’s Speech: Yes We Can. 2010 Web. December 31. http://barack-obama.nuvvo.com/lesson/4678-transcript-of-obamas-speech-yes-we-can

Parker, Glenn M.Team Playing and Teamwork: The New Competitive Business Strategy. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1991. [Print.].

Porter-O’Grady, Tim. What Motivation Isn’t. Nursing Management. 1982; 13.12:27–30. [Print.].

Porter-O’Grady, Tim. Of Mythspinners and Mapmakers: 21st Century Managers. Nursing Management. 1993; 24(4):52–55.

Powell Gary N., ed. Handbook of Gender and Work. London: Sage publications, 1999. [Print.].

Light Work: Being Watched May Not Affect Behavior, After All. June 4, 2009. [Web. January 17, 2011].

Riggs, Donald. The Crisis and Opportunities in Library Leadership. Journal of Library Administration. 2001; 32(3):5–17.

Rost, J.Leadership from the 21st Century. New York: Praeger, 1991. [Print.].

Scholtes, Peter R.The Leader’s Handbook: A Guide to Inspiring your People and Managing the Daily Workflow. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998. [Print.].

Schreiber, Becky, Shannon, John. Developing Library Leaders for the 21st Century. Journal of Library Administration. 2001; 32(3):37–60.

Tengblad, Stephen. Is there a ‘New Managerial Work’? A Comparison with Henry Mintzberg’s Classic Study 30 Years Later. Journal of Management Studies. 2006; 43:7.

Tuckman, Bruce, Jensen, Mary Ann. States of Small-Group Development Revisited. Group and Organization Studies. 1977; 2(4):419–427.

Winston, Mark D. Recruitment Theory: Identification of Those Who Are Likely to Be Successful as Leaders. Journal of Library Administration. 2001; 32(3):19–35.

Zaccaro, J. Stephen, Kemp, Carry, Bader, Paige. Leader Traits and Attributes. In: The Nature of Leadership. Eds. John Antonakis, Anna Cianciolo and Robert Sternberg. London: Sage Publications; 2004:101–124. [Print.].