CHAPTER 4

Experience—Cosmopolitanism and Managerial Effectiveness in a Global Context

In this chapter we turn our focus toward one group of people who we believe have the skills needed to succeed in leadership positions of high global complexity. “Even in this day and age and even with Fortune 500 companies, it is difficult to convince recruiting departments and managers of the benefit of hiring a student with multicultural sensitivity, who is bilingual, who has international exposure and a real knowledge of international business over a person with a (traditional) MBA” (Feldman & Tompson, 1992, p. 345). Such people might be called cosmopolitans. In the following pages we define cosmopolitans, discuss what the literature says about them, and hypothesize about the relationships between cosmopolitanism and other elements of our model.

Background

Our theoretical description of cosmopolitanism is based on interviews, personal experience, observation, and some data. We intend it to serve as a preliminary description, not as a factual case.

A cosmopolitan is not characterized by a particular personality profile, a particular IQ, a specific type of profession, or a specific background. There is no singular life experience that makes one person a cosmopolitan and another person not. The difference is that cosmopolitans have spent large portions of their lives oriented and focused externally to themselves and to their home culture. An interest and attention toward other cultures is a common thread among cosmopolitans.

Figure 5

A Conceptual Model of Predictors of Managerial Effectiveness in a Global Context (Experience)

Cosmopolitanism has been previously referred to in the literature, but the definition of the variable is much different from our conceptualization. Early in the last century Gale (1919) discussed the necessity of travel and education in creating a cosmopolitan citizen but did not relate those experiences to what one might learn through interaction with foreign cultures. The term cosmopolitan has also been used to describe media usage (McNelly, Rush, & Bishop, 1968), an attitude more accepting of integration (Caditz, 1976), and loyalty to the profession rather than to the employing organization (DeVries, 1971; Goldberg, 1976; Kirschenbaum & Goldberg, 1976; Rotondi, 1977).

For the purposes of our research, we viewed cosmopolitanism as describing an individual difference that Kanter defined as “a mindset that finds commonalties across places” (1995, p. 61). Cosmopolitans live in the context of their nation and the world rather than in the context of their local community (Hannerz, 1990; Ratiu, 1983). They not only understand that cultures and places differ, but they are also able to integrate themselves into different cultures in such a way that neither offends the other nor subverts the cosmopolitan’s own cultural orientations.

Because of their orientation toward others, cosmopolitans can develop skills that help them interact effectively with others different from themselves. They welcome other perspectives. Although they may prefer their own way of doing things, they are not parochial and do not ascribe to the “not invented here” philosophy. They will think about ideas that seem against their own cultural grain. Cosmopolitans are political in that they are aware of the impact of their behavior on others (personally and professionally); however, others may not perceive them as political in that their ability to see a variety of perspectives and integrate culturally different ideas give them the aura of mavericks within an organization.

Although there is no direct literature on cosmopolitanism as we have described it here, Ratiu (1983) investigated how international executives learned, examining a group of people very similar to our definition. He found that the “internationals” learned differently from those who were not described as internationals. The critical difference in learning styles was that internationals used stereotypes provisionally, dealt with the stress of interacting with different others by acknowledging it, and tended to be empirical in their understanding of other cultures in that they questioned rather than ascribed motivations. Other managers tended to believe that stereotypes were fairly enduring, did not acknowledge stress, and leaned toward ascribing motivations to behaviors. Ratiu did not investigate how these so-called internationals had acquired their skills. He stated that many of them had childhood experiences that had facilitated the development of these skills, but he did not explicitly identify which experiences were critical to developing them.

Although they did not talk directly about internationals, Kets de Vries and Mead (1992) described what they thought was critical in the development of the global manager. They discussed in detail what types of experiences good global managers would need to have and wrote about the specific types of experiences they expected them as having had in developing such skills. They proposed that in addition to standard technical competence and business experience, global managers would need to be able to interact effectively with people who were different. One way this skill could be learned, they suggested, was through a number of professional development factors including cultural diversity in family, early international experience, bilingualism, self-confidence, hardiness, envisioning, study in another culture, and study in an international environment.

Kets de Vries and Mead went on to say that early socialization into cross-cultural environments might be an important factor in the ability to work cross-culturally as an adult. They wrote: “Given the impact of childhood socialization on adult development, it is to be expected that early exposure is a determining factor in how successful the individual will be in dealing with cultural adaptability later in life” (1992, p. 193). Further, they wrote that “the strongest influences on both leadership qualities and the ability to adapt culturally stem from childhood background and psychological development. Following our framework, it can be said that in the development of a global leader ideally it helps to have a childhood background characterized by cultural diversity, one aspect being early international experience” (p. 200).

In 1999 Kets de Vries and Florent-Treacy wrote a book that examined the lives of Richard Branson, Percy Barnevik, and David Simon, three successful global leaders. While examining the technical competence and business savvy of these leaders, the authors also discussed their life experiences and their ability to work with others. What the authors found was that all three had spent time in their youths in situations that arguably would have increased their competence in interacting effectively with people possessing very different perspectives, especially a culturally different perspective. These three leaders worked across differences as part of their early life experiences and had developed a hardiness that helped them withstand the effort working across differences demanded.

In addition to skills developed from specific life events, the literature has suggested a variety of attributes relevant to the development of a cosmopolitan. From a developmental perspective, being able to take another’s perspective and “empathic accuracy” are critical to the ability to deal with different others (Davis & Kraus, 1997). Relational, cross-cultural, and interpersonal abilities are important to success in international environments (Pucik & Saba, 1998), as are cognitive complexity, emotional energy, and psychological maturity (Wills & Barham, 1994).

Cosmopolitans, then, can be viewed as developing through experience and the practice of specific skills. The development of these skills can begin in childhood or adulthood. A childhood beginning allows more time for practicing those skills. It is possible that individuals can develop cosmopolitan skills outside of work as an adult through cultural exposure (marrying into a culturally different family, for example, or through friendships) and interest (travel, for example, or formal educational opportunities such as foreign language study).

Cosmopolitans are not cultural chameleons. They can’t speak every language, do not know every point of etiquette in every culture, can’t tell you how to tip in every town, and do not know how to get a cab on the street in every place they visit. Although to others their cultural flexibility and adaptability may appear effortless, their balancing of varied cultural perspectives and their empathy for others different from themselves exerts a high price and is more difficult than interacting with people from what they would call their own culture. A cosmopolitan’s skill and orientation toward cultural adaptability is an interpersonal skill that helps them interact with others different from themselves, but it is worth noting that such a skill does not make such an individual better at the technical aspects of leadership.

Hypotheses

As local economies become increasingly globally oriented, more and more managerial positions require that people work or interact with others from different cultures (Aycan, 1997; Tung, 1997, 1998). These globally oriented positions differ widely in their complexity. Some require people to manage or interact with others across multiple time zones and who speak a variety of languages. Other positions require people to live and work in foreign environments for short assignments or for longer periods of time. Technical improvements in communication and travel have made it increasingly easy for companies to assemble teams of people who reside and work in different places, who speak different languages, and who carry with them different values and belief systems.

It has been suggested that people who are able to do work across cultures or internationally are more likely to be successful in a global economy (Bennett, 1989). We believe that those people we call cosmopolitans have the orientations and skills arising from life experiences that help them interact effectively with others different from themselves and, therefore, to be more successful global leaders.

To this end we operationalized cosmopolitanism as “early life” and “adult life” experience. Early life experience includes the number of languages spoken before age 13 and the number of countries in which the individual was educated. Experience gained later in life includes the number of countries in which the individual has lived, the number of languages spoken, and expatriate experience.

HYPOTHESIS 4.1: Cosmopolitanism will be positively correlated with bosses’ ratings of effectiveness.

HYPOTHESIS 4.2: Individuals who spoke/speak more languages in early life and adult life, who have lived in more countries, and who were educated in more countries will have higher scores on knowledge and initiative, success orientation, and contextually adept than individuals who have not had these experiences, regardless of the global complexity of their current jobs.

Given our description of cosmopolitanism and the list of factors that may contribute to the development of cosmopolitanism, how does cosmopolitanism relate to the variables we are examining in our model of managerial effectiveness? We anticipated a few specific relationships. It follows that the predisposition to be fascinated by the values and customs of others (openness) should be related to cosmopolitanism.

HYPOTHESIS 4.3: Cosmopolitanism will be positively related to the personality trait openness.

HYPOTHESIS 4.4: Managers who speak multiple languages and who have lived in multiple countries will have higher scores on the personality trait openness.

We also proposed a link between experience and capabilities. (For specifics on the capabilities and effectiveness turn to Chapter 3.)

HYPOTHESIS 4.5: Cosmopolitanism will be positively related to self-ratings of the capabilities of perspective taking, cultural adaptability, and international business knowledge.

HYPOTHESIS 4.6: Number of languages spoken before the age of 13 and number of countries educated in will each be positively associated with the capabilities of perspective taking, cultural adaptability, and international business knowledge.

HYPOTHESIS 4.7: Experience as an expatriate will be positively related to international business knowledge and cultural adaptability.

Results and Discussion

For purposes of this report, cosmopolitanism was operationalized in two ways. Both approaches took into account early and later life experience. They differed, however, in the way they related to the model. We first operationalized cosmopolitanism as a continuous variable (the linear addition of number of languages currently spoken, number of countries lived in, number of languages spoken before age 13, and number of countries educated in) because we believed that a combination of experiences contribute to the development of cosmopolitanism. We did not hypothesize that job complexity would affect the relationships between cosmopolitanism and any of the other variables in the model. Hypotheses 4.1, 4.4, and 4.6 were examined using an additive variable—cosmopolitanism. Results indicated that an individual’s level of cosmopolitanism was negatively related to the bosses’ ratings of internal relationships (r = –.182, p < .015), but was not related to bosses’ ratings of other criterion variables (Hypothesis 4.1). These results suggested that people with higher cosmopolitanism scores were at a disadvantage with their bosses because their bosses perceived them as being less proficient at internal relationships than those with lower cosmopolitanism scores.

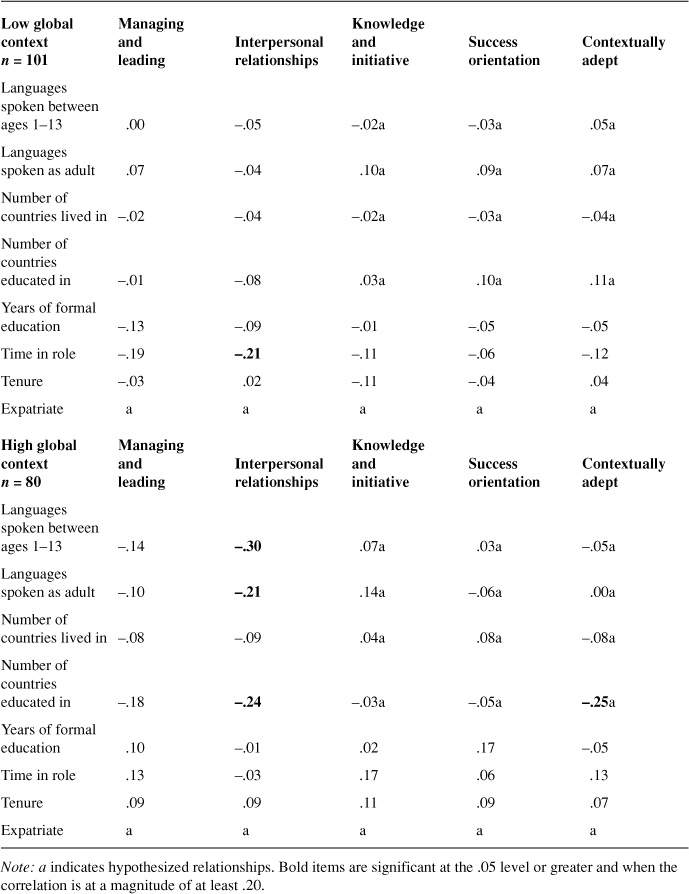

Results for hypotheses related to early and adult life experience (4.2, 4.3, 4.5, and 4.7) are shown in Tables 4.1–4.3. In Table 4.1 zero-order correlations between experience variables and effectiveness criteria are presented. Hypothesis 4.2 was not supported. In fact, for managers in the high global condition, number of countries educated in and number of languages spoken as a child and as an adult were negatively correlated with the criterion measures interpersonal relationships and contextually adept. Number of countries educated in was also negatively correlated with interpersonal relationships for managers in domestic jobs. For the local-boss ratings, time in role was negatively correlated with interpersonal relationships.

Hypothesis 4.3 was not supported (see Table 4.2). Results indicated that cosmopolitanism was not correlated with openness (r = .067, p < .332). This result suggested that openness as measured in the NEO PI-R was not necessarily related to the type of past international experience captured by the cosmopolitanism variable. Hypothesis 4.4, which predicted an association between adult life experience and the trait openness, was also not supported.

As seen in Table 4.3, Hypothesis 4.5 was supported. Results indicate that cosmopolitanism is positively correlated with international business knowledge (r = .481, p < .001) and cultural adaptability (r = .388, p < .001). This result suggested that international business knowledge and cultural adaptability were related to the type of past international experience captured by the cosmopolitanism variable and is useful with regard to specific competency areas that individuals can develop.

Table 4.1

Early Life and Adult Life Experience Correlations with Boss Effectiveness Ratings for Managers in Low and High Global Contexts

Table 4.2

Early Life and Adult Life Experience Correlations with Personality Scales for Managers in Low and High Global Contexts

Hypothesis 4.6 was partially supported. Number of countries educated in was positively correlated with the capabilities of cultural adaptability and international business knowledge for all managers. Number of languages spoken between ages 1–13 was only associated with cultural adaptability and international business knowledge for managers working in a high global context.

Hypothesis 4.7 was supported for high-global-context managers and partially supported for low-global-context managers. In other words, for managers in either context, experience as an expatriate was associated with the skill of cultural adaptability. It was not related to international business knowledge for low-global-context managers but was for high-global-context managers.

Another interesting outcome is that bosses perceived people with high cosmopolitanism scores as being less proficient with internal relationships. This is particularly interesting given the relationship between cultural adaptability and bosses’ positive evaluation of the managers. This result may suggest that bosses are uncomfortable with people with a cosmopolitan orientation, even though it is related to precisely the competencies considered necessary for success in a globally complex job.

Table 4.3

Early Life and Adult Life Experience Correlations with Selected Capabilities for Managers in Low and High Global Contexts