CHAPTER 3

Managerial Capabilities—Learning and Effectiveness as a Global Manager

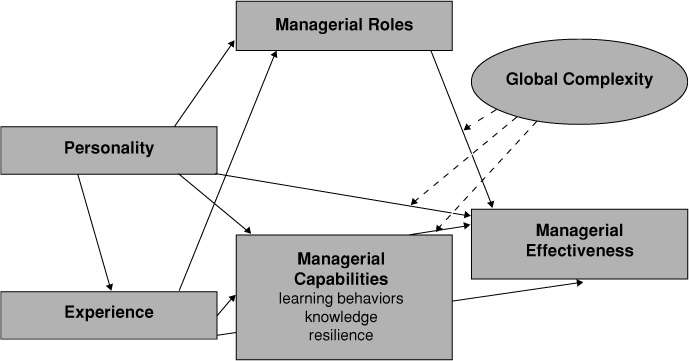

In our conceptual model we explored learning and effectiveness in global roles from several perspectives. These included the direct relationship of experiential learning to managerial effectiveness in the global role, specifically past experience managing diverse workgroups in one’s own country (cultural heterogeneity) and experience with other cultures through early language training and by living in more than one country as a child and adolescent (cosmopolitanism). (These topics are addressed in Chapters 4 and 5.) In this chapter we explore the relationship of three specific learning behaviors to managerial effectiveness in jobs of high and low global complexity (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

A Conceptual Model of Predictors of Managerial Effectiveness in a Global Context (Managerial Capabilities)

Background

In the United States over the past two decades, scholars have used the ability to learn from workplace experiences as a major construct to explain career success (attaining a senior-level organizational position) and managerial effectiveness. Researchers have argued that the opportunity and willingness to engage in a variety of work-based experiences and the ability and willingness to learn and adapt as a result are key factors in explaining managerial development and subsequent effectiveness (Keys & Wolfe, 1988; McCall, Lombardo, & Morrison, 1988; McCauley, 1986; Morrison & Hock, 1986; Nicolson & West, 1988; Spreitzer, McCall, & Mahoney, 1997).

More recently, taxonomies of global leadership skills and capacities have suggested that learning is a key to success in the global role. For example, Kanter (1995) has described an individual able to “learn from and leverage the heterogeneity and chaos of the worldwide market place.” Gregersen, Morrison, and Black (1998) have listed the characteristic of inquisitiveness as an essential trait of the effective international manager. Spreitzer, McCall, and Mahoney (1997) have identified those who search for opportunities to learn, seek and use feedback, remain open to criticism, and are flexible and cross-culturally adventurous as more likely to be effective in an international executive role.

Hypotheses

Learning behaviors. The learning capabilities that we adopted for use in our model were self-development, perspective taking, and cultural adaptability. In introducing learning capabilities and skills into the model we wanted to understand if the learning behaviors associated with experiential or action learning would interact with global complexity to predict managerial effectiveness. To the extent that they did, we wanted to explore how people develop these learning skills. Were learning skills related to personality traits such as emotional stability (neuroticism) and openness to experience? Was the ability to learn related to personality, or did adult experiences of cultural heterogeneity and early life experiences with diverse cultures better account for such an ability? Could managers acquire these learning behaviors?

To the extent that learning skills proved to be associated with effectiveness in the global role, and to the extent that learning skills could be understood as trait based or experience based, we cast the process of developing individuals for global managerial responsibilities as either a selection issue, a development issue, or both.

Self-development. Self-development describes a set of behaviors people would exhibit were they to take responsibility for their own development. It is meant to exemplify a person who adopts an active rather than passive stance in regard to his or her own development. Behaviors that typify this kind of learning orientation include a demonstrated awareness of one’s own strengths and weaknesses, openness to feedback about one’s actions, and eagerness to engage in new experiences.

In the U.S. practitioner-oriented literature (for example, Dalton & Hollenbeck, 1996; McCall, Lombardo, & Morrison, 1988), scholars have considered self-awareness and personal development key competencies for managerial effectiveness. Individuals who possess these competencies are presumed to have developed into better managers and leaders because these self-development behaviors have allowed them to become more skilled (Tesluk & Jacobs, 1998).

Little empirical research exists to back up these presumptions and suppositions. Instead, the beliefs about the importance of self-development rely on a value set taken from the traditions of the psychotherapy literature—self-awareness as the first step in a behavior-change process (Freud, 1960)—and the goal setting and knowledge-of-results literature (for example, Locke & Latham, 1984). An American and European literary and philosophical tradition that holds self-knowledge as a valued human trait also plays a part.

On their measure of learning agility, Lombardo and Eichinger (1994) demonstrated a partial conceptual overlap with the self-development construct we have presented in our model. Dalton and Swigert (1999) reported modest relationships between the learning versatility construct and the learning behaviors necessary to engage in workplace learning, but found no significant relationship between boss and peer ratings of potential effectiveness and self-reported ratings of learning versatility.

Spreitzer, McCall, and Mahoney (1997) investigated the relationship of learning skills to international effectiveness. They constructed six scales to measure the ability to learn from experience: (1) seeks opportunities to learn, (2) seeks feedback, (3) uses feedback, (4) is open to criticism, (5) is flexible, and (6) is cross-culturally adventurous. The first four of these scales overlap with the content of our self-development construct. Spreitzer et al. reported the relationship between a boss’s rating of his or her direct reports on these scales and the boss’s rating of the likelihood that these same direct reports would be successful in an international assignment. In our study, two of the scales that we included in the self-development construct, seeks opportunities to learn and is open to criticism, were modestly related to boss ratings of success on international assignments. However, the independent and dependent variables in this research were both rated by the boss, so same-source bias clouds our interpretation of the results.

On the Benchmarks® developmental instrument (Lombardo & McCauley, 1988), the scale self-awareness includes items about a person’s willingness to seek and attend to feedback from others. This measure demonstrated a significant relationship to boss ratings of promotability and to longitudinal measures of organizational progress but not to independent assessments of promotability or effectiveness evaluations.

We were unaware of any other studies that have tested the relationship of self-development skills to managerial effectiveness, particularly for managers with international responsibilities.

HYPOTHESIS 3.1: Self-development will share significant variance with all effectiveness criteria for managers in the low-global-context group.

This hypothesis was tentative. It may hold only to the extent that the manager was working in a culture where active attention to one’s self and one’s career growth is considered appropriate. (Our data did not allow us to entertain this perspective.) For example, some cultures (Japanese or Middle Eastern, for example) consider seeking feedback poor form. Managers in these cultures wait to receive assignments and do not seek them out (Dalton, 1998). Some cultures can view self-development strategies as inappropriate because they represent undue attention to the individual. This is characteristic of cultures in which the self is considered an interdependent rather than an independent construct (Cross, 1995). Schwartz’s concept of work centrality suggested that in some cultures one’s work experience is secondary to the totality of one’s life experience (1999). An undue focus on attaining skills to advance one’s career might in such cultures run counter to norms and expectations.

Nonetheless, it is important to address the relationship of self-development to managerial effectiveness because much of executive development in the United States is based on the notion of self-development. This kind of assumption causes problems when U.S.-based leadership-development professionals try to introduce these concepts to international organizations.

Perspective taking. The set of skills and behaviors defined as perspective taking describe a person who is able to listen well; is able to consider multiple points of view, multiple possible solutions, and multiple perspectives; and is able to entertain empathy toward another person’s point of view. Perspective taking can perhaps be seen as what Gardner (1983) has called one of the “personal intelligences.”

Gardner (1983) wrote of six basic intelligences: (1) linguistic, (2) musical, (3) logical-mathematical, (4) spatial, (5) bodily-kinesthetic, and (6) personal. The area of personal intelligence includes self-knowledge (intrapersonal) and knowledge of other people (interpersonal). He considered these personal intelligences as different from the other five. In his view, intrapersonal intelligence represents access to one’s own emotional life. Interpersonal intelligence is the ability to notice and make distinctions among other individuals, particularly among their moods, temperaments, motivations, and intentions. Unlike the other intelligences, however, “the varieties of personal intelligence prove much more distinctive, less comparable, perhaps even unknowable to someone from an alien society. (T)he ‘natural course’ of the personal intelligence is more attenuated than that of other forms, inasmuch as the particular symbolic and interpretive systems of each culture soon come to impose a decisive coloring on these latter forms of information processing” (p. 240).

Gardner’s view affected our work in that when we discuss perspective taking (and further, when later in this report we discuss cultural adaptability) we are dealing with the highest manifestation of these intrapersonal and interpersonal intelligences. Ideally an effective global manager can rise above his or her own cultural understanding of self and others, translating his or her intrapersonal and interpersonal intelligence capacity into the symbol system of another culture. Perspective taking is the ability to transform one’s meaning structures; in other words, individuals make sense of what they know within a network of values, beliefs, attitudes, and past experiences, interpreting what happens to them through this cultural framework. When they (managers, in this case) work with individuals from other cultures, they encounter people who behave in ways that are incongruent with their own expectations of behavior. If managers interpret and label what others are doing through their own interpersonal framework, they may make incorrect assumptions about others’ motivations and respond incorrectly. If managers are able to take the perspective of others, they can transform their understanding, alleviating the anxiety brought about by encountering and dealing with people who have different value systems.

We knew of no empirical work that related the ability to take the perspective of another to international managerial effectiveness. In his counseling work with college students, Perry (1981) described a developmental progression of movement from dualism to contextual relativism—the ability to make judgments in a relative context while holding one’s own values constant. In the sojourner literature summarized by Kealy (1989), many researchers were reported to have agreed that empathy, interest in the local culture, flexibility, tolerance, and technical skill predict success (defined as adjustment) in another culture. Our construct perspective taking may capture the concepts of empathy, flexibility, and tolerance.

At the theoretical level, Mezirow (1991) wrote of learning through perspective transformation. “We encounter experiences, often in an emotionally charged situation, that fail to fit our expectations and consequently lack meaning for us, or we encounter an anomaly that cannot be given coherence either by learning within existing schemes or by learning new schemes. Illumination comes only through redefinition of the problem. We redefine old ways of understanding” (p. 94).

Given our understanding of perspective taking and managerial work in high-global-complexity conditions, we designed the following hypotheses:

HYPOTHESIS 3.2: Perspective taking will share significant variance with the effectiveness criteria managing and leading, interpersonal relationships, success orientation, and contextually adept when the manager’s work is more globally complex.

HYPOTHESIS 3.3: Perspective taking will be positively associated with the personality scale openness.

HYPOTHESIS 3.4: Perspective taking will be negatively associated with the personality trait neuroticism.

Cultural adaptability. Cultural adaptability is defined as a set of behaviors used by a person motivated to understand the influence of culture on behavior and who has the skills to learn about and use cultural differences. More than the capacity to understand a particular culture, it describes a person who is able to work well across multiple cultures. Cultural adaptability may be a special case of perspective taking. Cultural adaptability may also encompass the cultural empathy construct identified by Ruben (1976) and Cui and Van Den Berg (1991).

The construct of cultural adaptability is an old one, grounded in the training literature of institutions such as the Peace Corps, religious missionary communities, the diplomatic corps, the military, and the business community. Each of these groups has struggled to prepare people to work effectively in other cultures (see, for example, Hannigan, 1990). What differentiates these various constructs and definitions is the role the sojourner plays and the results the group seeks. For example, the struggle for the Peace Corps volunteer is to relocate and to adjust to living in another culture, assuming the role of teacher and helper. The role of the international diplomat is to relocate and to adjust to living and working in another culture in order to represent the interests of the diplomat’s country at a high level of political sensitivity and potential visibility. The role of the military spouse may be to relocate and to adjust to living in an enclave of fellow expatriates.

The role of the global manager is different from these roles in that the global manager often does not relocate and so does not face the adjustment so often described in the literature. Rather, the global manager manages as a traveler and/or from a distance and is responsible for activities in multiple countries simultaneously, countries that do not share a common culture. Therefore, we are uncertain that the literature on cultural adjustment will help us understand the skill of cultural adaptability as we define it: the need to know how to adapt quickly in multiple and ever-changing cultural contexts in which interactions are sometimes face-to-face and sometimes at a distance.

Additionally, much of the existing literature has spoken to the criterion measure of cross-cultural adjustment rather than to the criterion measure of work effectiveness. We are interested in the criterion measure of work effectiveness as seen through the eyes of the target manager’s boss.

Studies conducted by McCall, Spreitzer, and Mahoney (1994) and Spreitzer, McCall, and Mahoney (1997) have helped us develop our hypothesis related to leadership effectiveness. Their taxonomy of competencies and learning skills, hypothesized to predict success as an international manager, included a learning skill operationalized as adapts to cultural differences. They presented this five-item scale in a subsequent factor analysis of the data as two scales: sensitive to cultural differences and is culturally adventurous. Boss ratings of an individual’s potential to be successful as an international manager and as an expatriate were found to be significantly correlated with boss ratings of an individual’s perceived skill on these two items. (In this research the outcome criteria were related to work effectiveness and not adjustment.) Using this scale as the basis for our own construct of cultural adaptability, we formed the following hypothesis:

HYPOTHESIS 3.5: Cultural adaptability will share significant variance with the effectiveness criteria managing and leading, interpersonal relationships, knowledge and initiative, success orientation, and contextually adept when the work is more global in scope.

Several other studies provide the context for our additional hypotheses. For example, Oberg (1960), a pioneer in studying cross-cultural adjustment, coined the term culture shock. People constantly monitor, interpret, and explain the behavior of themselves and others as part of interacting with one another. When dealing with people from other cultures, the behaviors are the same—but the meaning attributed to the behaviors differs. Culture shock represents the anxiety resulting from trying to process and understand how the world works when cultural significance is unmoored.

As Adler stated, “Culture shock is a form of anxiety which results from the misunderstanding of commonly perceived and understood signs of cultural interaction” (1975, p. 13). Adler treated culture shock as a developmental opportunity, an experience that allows a person to first understand the relativity of his or her own value set and then to investigate, reintegrate, and reaffirm a relationship to others.

Anderson (1994) divided the cultural-adaptation literature into four major models: (1) the recuperation model, (2) the learning model, (3) the journey model, and (4) the homeostatic model. She suggested that it is a mistake to consider cultural adaptation as different from many other transitional processes, arguing that cultural adaptation is simply an accommodation to change. Using Anderson’s conceptualization of multiple models of cultural adaptability, we would place our view in the camp of the homeostatic model (Grove & Torbiorn, 1985; Torbiorn, 1982), which holds that cultural adaptation requires a change in one’s perceptual frame and behavior in order to adapt to the ambient environment.

Cui and Awa’s (1992) construct of intercultural effectiveness encompasses language ability, interpersonal skills, empathy, social interaction, managerial ability, and personality traits. This is similar to our conceptual model, which incorporates life experiences, personality traits, role skills, and capacities as predictors of perceived managerial effectiveness. We note, however, that Cui and Awa’s interest in this work was the sojourner expatriate, not the global manager.

Because the global manager is constantly being exposed to cultural differences, sequentially and in parallel, we argue that the ability to manage culture shock will affect the manager’s effectiveness:

HYPOTHESIS 3.6: Cultural adaptability will be grounded in one’s ability to manage the anxiety associated with the dissonant messages of the foreign workplace and thus will be highly correlated with emotional stability (neuroticism).

Finally, we wanted to address the skill of cultural adaptability itself. If this is a skill highly related to effectiveness as a global manager, then who is most likely to have this skill or to be able to acquire it? How do people acquire cultural adaptability? To answer that question we believed it was important to go beyond the “how” to the “why.” Why might individuals who are willing to entertain novel ideas and unconventional values be better prepared and more motivated to deal with another kind of difference? The psychological theory of mere exposure might partially explain this phenomenon. This theory has argued that if individuals have repeated exposure to a stimulus, they will develop an increase in positive affect toward that stimulus (Zajonc, 1968). In 1989 Bornstein explained it further: It is advantageous to human beings to prefer the familiar over the novel. The familiar is safe and unpredictable; the unfamiliar is unsafe and unfamiliar. Bornstein argued that there is an evolutionary reason for this and suggested that it is an adaptive human trait. If this is the case, then individuals exposed to cultural differences early in life or career will have a broader sense of what constitutes the familiar than will individuals who have not been so exposed. They will not experience the cultural “other” as unfamiliar, they will experience less anxiety around what presents itself as different, and they will seek out more international experiences.

In contrast to the mere exposure theory’s behavioral explanation for the skill of cultural adaptability, we wished to address the personality trait openness and its posited relationship to cultural adaptability. This trait, as measured by the NEO PI-R, is made up of six facet scales: aesthetics, fantasy, values, feelings, ideas, and actions. Of all the traits measured by the FFM, this construct has proven the most problematic for researchers. Some authors have equated it to intelligence and divergent thinking, others to creativity (Costa & McCrae, 1992). In the workplace-effectiveness literature, openness has been most often related to effectiveness in training programs, not to job-effectiveness criteria. In our work we hypothesized as follows:

HYPOTHESIS 3.7: Openness will be positively associated with the learning scale cultural adaptability.

Knowledge. A large body of literature already exists that demonstrates the relationship of job knowledge to managerial effectiveness (see, for example, Kotter, 1982). For that reason we did not devote a chapter of this report to a review and explanation of this variable in our model. Still, we believed it essential to include business knowledge and international business knowledge in our model. Knowledge seemed to fit best in a chapter that discussed learning. We made the following propositions regarding the relationship of business knowledge and international business knowledge to effectiveness in managerial jobs of high and low global complexity:

HYPOTHESIS 3.8: Business knowledge will share significant variance with the effectiveness criteria knowledge and initiative and success orientation regardless of the global complexity of the job.

HYPOTHESIS 3.9: International business knowledge will share significant variance with the effectiveness criteria knowledge and initiative and success orientation when the manager’s work is more globally complex.

HYPOTHESIS 3.10: The capability insightful will share significant variance with the effectiveness criteria knowledge and initiative and success orientation regardless of the global complexity of the job.

HYPOTHESIS 3.11: Conscientiousness will be related to bosses’ ratings of business knowledge and international business knowledge.

HYPOTHESIS 3.12: Business knowledge and international business knowledge will be positively associated with conscientiousness.

Resilience. There was also a substantial body of literature relating the construct of resilience to job satisfaction and job effectiveness (for example, Maddi & Kobassa, 1984). The constructs representing resilience and integrity in our model were placed in this chapter to connect the idea that those individuals most likely to demonstrate learning behaviors will be those who are able to cope with the uncertainties and ambiguities associated with learning. We made the following propositions regarding the relationship of integrity and coping with stress to effectiveness in managerial jobs of high and low global complexity.

HYPOTHESIS 3.13: The ability to cope with stress will share significant variance with all effectiveness criteria when the manager’s work is more globally complex.

HYPOTHESIS 3.14: Integrity will share significant variance with managing and leading and interpersonal relationships regardless of global complexity.

We further hypothesized two relationships between managers’ resilience capabilities and their personality traits.

HYPOTHESIS 3.15: The skill of coping will be negatively associated with the trait neuroticism.

HYPOTHESIS 3.16: Time management will be positively associated with conscientiousness.

Capabilities importance. Finally, we hypothesized about the degree of importance global managers would place on different capabilities within the scope of high global complexity.

HYPOTHESIS 3.17: Managers in contexts of high global complexity will attribute more importance to the capabilities of cultural adaptability and perspective taking than will managers in contexts of low global complexity, but managers in either context will perceive the capability of self-development equally.

HYPOTHESIS 3.18: Managers in contexts of high global complexity will attribute more importance to the capability of international business knowledge than will managers in contexts of low global complexity, but managers in either context will perceive the capability of business knowledge equally.

HYPOTHESIS 3.19: Managers in contexts of high global complexity will attribute more importance to the capabilities of time management and coping than will managers in contexts of low global complexity, but managers in either context will perceive the capability of integrity equally.

Results and Discussion

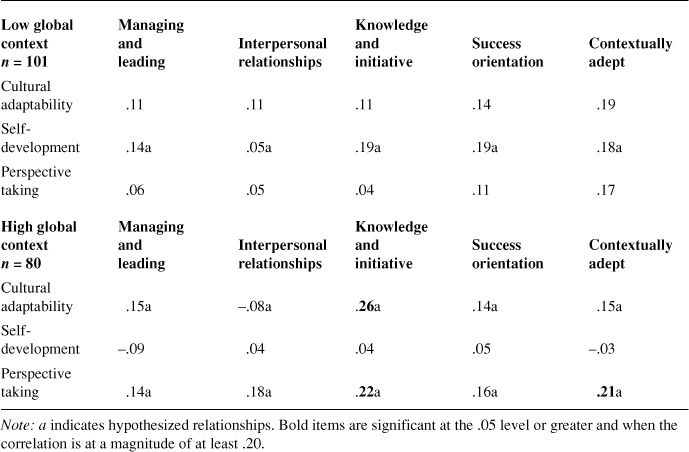

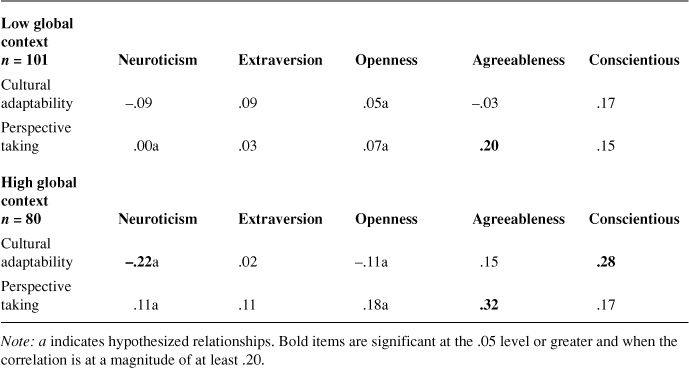

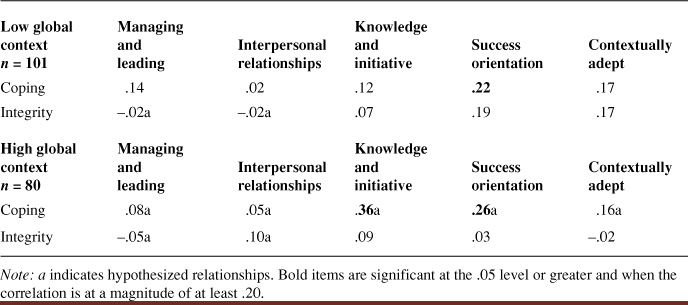

Learning. Zero-order correlations were conducted between the three learning scales and the five effectiveness criteria as rated by their bosses and self-reported personality scales for local and global managers (see Tables 3.1 and 3.2). Hypothesis 3.5 was supported. Hypothesis 3.1 was not supported. There was partial support for Hypothesis 3.2. Only the learning scale perspective taking was significantly related to criterion measures and only in the high-global-complexity condition.

Table 3.1

Learning Behavior Scale Correlations with Effectiveness Ratings for Managers in Low and High Global Contexts

Table 3.2

Learning Behavior Scale Correlations with Personality Scales for Managers in Low and High Global Contexts

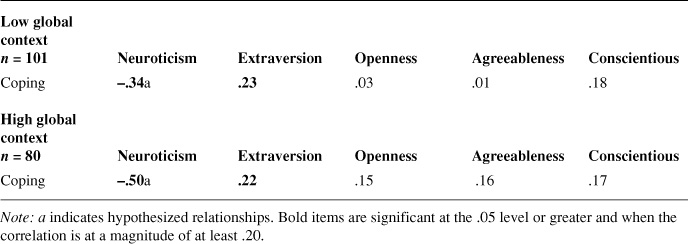

Hypotheses relating the learning behavior scale perspective taking to the personality trait neuroticism were not supported, but as predicted there was a significant and positive relationship between agreeableness and perspective taking. The capability cultural adaptability was related to neuroticism as predicted in Hypothesis 3.6, but was not related to openness as was hypothesized in 3.7. These results suggest that managers adept at perspective taking are more likely to have the traits of emotional stability and agreeableness—which includes trust in and consideration for others, candor, and sympathy.

Knowledge. Zero-order correlations were conducted between the three knowledge scales, the five effectiveness criteria, and personality. The results can be seen in Tables 3.3 and 3.4. Hypothesis 3.8 was supported only for the global condition. Hypothesis 3.9 was supported. Hypothesis 3.10 was supported only for the local condition. Business knowledge and international business knowledge are significantly related to the criteria in the high-global-complexity condition but not the low-global-complexity condition.

The hypothesized relationship between business knowledge, international business knowledge, and conscientiousness was partially supported for managers working in a low global context and fully supported for managers working in a high global context. Conscientiousness for managers in the high global context was related to the skills business knowledge and international business knowledge.

Table 3.3

Knowledge Scale Correlations with Effectiveness Ratings for Managers in Low and High Global Contexts

Table 3.4

Knowledge Scale Correlations with Personality Scales for Managers in Low and High Global Contexts

Resilience. The zero-order correlations presented in Table 3.5 address Hypotheses 3.13 and 3.14. They reflect the association between the resilience scales, the five effectiveness criteria as rated by bosses, and personality scales for domestic and global managers. Hypothesis 3.13 was partially supported. Resilience was only associated with bosses’ ratings of knowledge and initiative and success orientation. Hypothesis 3.14 was not supported. The scale coping is related to boss-criterion ratings in both the low- and high-global-complexity condition. Time management, although identified by managers in the high global context as important to their jobs, was not significantly related to any of the effectiveness criteria.

Table 3.5

Resilience Scale Correlations with Effectiveness Ratings for Managers in Low and High Global Contexts

As shown in Table 3.6, Hypothesis 3.15 was supported. Hypothesis 3.16 was not supported.

Table 3.6

Resilience Scale Correlations with Personality Scales for Managers in Low and High Global Contexts

Capabilities importance. Both independent sample t-tests and nonparametric Mann–Whitney U analyses were conducted to test for mean differences reported by low- and high-global-complexity managers on the level of importance attributed to the eight capabilities. The results are presented in Table 3.7. Hypothesis 3.17 was partially supported; differences were found for cultural adaptability but not perspective taking. Hypothesis 3.18 was supported. Hypothesis 3.19 was partially supported as differences were found for time management but not coping. Managers in high-global-complexity jobs were statistically more likely to endorse the capabilities of cultural adaptability, international business knowledge, and time management as extremely important to their current job.

The two groups did not differ in the importance they ascribed to the remaining capabilities (self-development, perspective taking, business knowledge, insight, coping, and integrity).

Table 3.7

Capabilities Importance Ratings for High- and Low-Global-Complexity Jobs

| Managerial capabilities | |

| Cultural adaptability | T = –8.27 p < .001 low = –.48, high = .50 |

| Self-development | NS |

| Perspective taking | NS |

| Business knowledge | NS |

| International business knowledge | T = –7.69 p < .001 low = –.46, high = .46 |

| Time management | T = –2.05 p < .05 low = –.13, high = .14 |

| Coping | NS |

| Integrity | NS |