CHAPTER 5

Experience—The Influence of Diversity on Managerial Effectiveness

Demographic changes all over the world have intensified the cultural diversity of today’s labor force. Concurrently, a shift has occurred toward more complex jobs and roles in multinational corporations. The increased complexity of roles and increased interactions among diverse people has yielded practical concerns regarding the influence of diversity on individual and group effectiveness. Whether or not perceived similarity among group members affects workgroups’ outcomes is a target of a considerable amount of research. The relative distance between members who are perceived to be in-group members (“one of us”) versus those who are perceived as outsiders (“one of them”) has been shown to have both adverse and positive consequences. But what influence does organizational diversity exert upon the perceptions of success at domestic and global work?

This chapter focuses on how experience with diversity influences social behavior in global organizations and in the perceptions of a manager’s effectiveness. We present several theoretical propositions that explain how individuals relate to those who are different from and similar to themselves. We also explore how working with heterogeneous workgroups affects long-term success and the impact of the manager’s “fit” in culturally diverse organizations.

Background

We have used diversity to refer to situations in which managers are not alike with respect to some attribute(s). At an individual/interpersonal level, one can view diversity in several ways. One way is through one’s own ethnocentrism (the tendency to judge other cultures by one’s own standards). To eliminate ethnocentrism, one must reject one’s own culture—a very rare occurrence even for individuals who spend a considerable amount of time outside of their native country (Triandis, 1995). Another view of diversity is based on beliefs of perceived similarity. On one hand, in a homogeneous environment an individual has a very narrow range of attributes that define who comprises the in-group. On the other hand, in a heterogeneous environment the range of attributes that distinguish in-group members from outsiders is much larger.

Many theorists and researchers have addressed the construction of the self in relationship to the group. In the context of global organizations, one might assume that individuals would have at least three reference groups (a group to which people refer when making evaluations about themselves and their behavior): one belonging to their native culture, one belonging to the culture with which they come in contact (Ferdman, 1995), and one belonging to the organizational culture. LaFrombosie, Coleman, and Gerton (1993), in a review of the literature, identified five types of models used to describe psychological processes, social experiences, and general obstacles in the context of biculturalism, and more models exist (see, for example, Cox, 1993). But those studies have not addressed the implications of one’s identity on effectiveness, most particularly when the context of that effectiveness is a global organization.

Researchers have frequently used the social identity and social categorization process, the similarity-attraction paradigm, informational and decision-making theories, and the degree of distinctiveness (Williams & O’Reilly, 1998) to explain the effects of diversity on organizational effectiveness.

Social identity and social categorization refer to the process whereby people derive at least part of their identity from the social categories to which they belong, using those categories to categorize others as similar or different from themselves. Arbitrarily categorizing people based on perceived differences can lead to trust and cooperation conflicts between in- and out-group members (Brewer, 1979, 1995).

The similarity-attraction paradigm has suggested that similarity between people produces positive effects by validating the perceiver’s worldview. “Presumably, similarity in demographics leads to an inference or assumption about similarity in values, beliefs, and attitudes. Furthermore, a presumed knowledge of the other individual’s values, beliefs, and attitudes leads to a sense of predictability, comfort, and confidence regarding the other individual’s likely behavior in the future” (Tsui, Xin, & Egan, 1995, p. 108). Some research has shown demographic similarity to be related to more frequent communication and friendship ties (Lincoln & Miller, 1979), frequency of technical communication (Zenger & Lawrence, 1989), and social integration (O’Reilly, Caldwell, & Bartette, 1989). In other words, research has supported the belief that workplace homogeneity makes communication and relationships easier.

Informational and decision-making theories (Tziner & Eden, 1985) have suggested that group heterogeneity can have a positive impact through the increase in the skills, abilities, information, and knowledge that diversity brings to the group. When the task or work can benefit from multiple perspectives and diversified knowledge, diversity can have a positive impact.

Lastly, the degree-of-distinctiveness theory has suggested that the more distinctive an individual is, the more self-aware he or she will become. That individual’s self-awareness in turn leads him or her to compare his or her behavior to the norms of the group. According to Thomas, Ravlin, and Wallace (1996), a large cultural difference could result in unsuccessful adaptation or decreased effectiveness due to the perceived effort required just to fit in with the group.

The depth and breadth of the literature on the influence of diversity has directed our attention toward two particular aspects: the influence of experience working in heterogeneous work groups and the influence of organizational demography on effectiveness. Phrased another way, we wanted to know if experience in managing a diverse workgroup in a domestic role increases the likelihood that an individual will be effective in a global role. We also wanted to know if experience, as part of a demographic cohort, impacts perceptions of a manager’s effectiveness.

Hypotheses

Influence of experience working in heterogeneous workgroups. It can be argued that managers who have had positive experiences managing domestic heterogeneous workgroups (workgroups composed of members who are different in demographic and cultural characteristics) could also be effective in an international assignment. We have indicated that relationship on our conceptual model (see Figure 5, p. 43). Experience working with diverse workgroups may indeed become the foundation for developing interpersonal skills that are effective and appropriate for working across cultural and geographic boundaries. The literature has suggested that skills which are helpful in interacting with people from other cultures can be learned by working with heterogeneous groups (Cox & Beale, 1997; Jackson, Brett, Sessa, Julin, & Peyronnin, 1991; Jackson, May, & Whitney, 1995; Sessa & Jackson, 1995). Scholars have argued that demographically diverse workgroups offer different perspectives, attitudes, and abilities: “Differences in experiences and perspectives lead team members to approach problems and decisions drawing on different information, from different angles, and with different attitudes. Therefore teams composed of people with diverse backgrounds and characteristics are expected to produce a wider variety of ideas, alternatives, and solutions—and thus perform better—than teams composed of people who are similar in terms of demographic characteristics” (Sessa & Jackson, 1995, p. 140). Research has also supported the link between group diversity and a positive impact on group effectiveness (Sessa & Jackson, 1995). Short-term outcomes of working with heterogeneous groups include the raising of self-awareness and increased social familiarity (Jackson et al., 1995).

The study of how a manager’s previous work history with heterogeneous workgroups affects the development of interpersonal skills and the capacities required in a global role is new. But because we assumed that working with a heterogeneous workgroup leads to the development of these skills, two conclusions were possible: (1) domestic or local managers who excel in this area may be particularly well suited for global leadership assignments, and (2) working with heterogeneous groups can be used for development of skills that impact effectiveness. Therefore,

HYPOTHESIS 5.1: When the work is more globally complex, managers with a history of working in heterogeneous workgroups in their most recent domestic job will have higher scores on all effectiveness criteria than will their counterparts without this history.

There was substantial evidence, however, that suggested that increased diversity in workgroups has negative effects on the ability of the group to function effectively over time (Williams & O’Reilly, 1998). Diverse groups are more likely to have difficulty integrating, communicating, and resolving conflict. As the work becomes more global (that is, as time, geography, and cultural distance expand), maintaining workgroup cohesiveness becomes even more complex.

The influence of organizational cohort homogeneity. In addition to the impact of a manager’s work history with heterogeneous workgroups, we believed the manager’s similarity to colleagues was an important factor in trying to understand perceptions of success. Exploration of the relationship of demographic variables and workers’ attitudes has had a long tradition in industrial and organizational psychology, social psychology, and sociology. Very few studies have examined how variations in multiple demographic variables affect work effectiveness, in particular the effectiveness of managers working in global organizations.

Organizational demography (Pfeffer, 1981, 1983) has treated demographic variables as a compositional property of the group or unit by measuring the variance in demography within the unit and relating this unit property to unit outcomes.1 That compositional component has distinguished it from other demographic approaches.

Two main contributions have typically characterized organizational demography research: compositional variables (such as relative homogeneity or heterogeneity) and methodological ease (Lawrence, 1997). Researchers have mapped most often the relationship between demographic variables and organizational outcomes. The relationship between the demographic predictor and the outcome has been reflected in the literature as a varied assortment of theoretical explanations. Relational demographers have treated demography as a group-level variable but have also analyzed it at the individual level (Tsui & O’Reilly, 1989). “In these studies, the relative similarity or dissimilarity of specific demographic attributes of group members is related to individuals’ attitudes or behaviors” (Thomas, Ravlin, & Wallace, 1996, p. 3).

Lawrence (1997) characterized five defining boundaries of organizational demography: (1) the demographic unit selected for the study, (2) the attributes of the demographic unit, (3) the domain in which the attributes are studied, (4) the measures of the attributes, and (5) the mechanism by which the attributes predict outcomes. The demographic unit can range from small (such as an individual) to large (such as an industry). The unit is the entity to which theoretical generalizations are made. Attributes of the demographic unit are the characteristics used to depict the subject matter under study (such as organizational tenure). The domain is the context in which a demographic unit is studied. The domain’s level of analysis is higher than or equal to the demographic unit under study. Domains also range in size from dyads or groups to organizational populations or industries. Measures of the attribute that depict the demographic unit or domain are either simple (such as the organizational tenure of an individual in a group) or compositional (such as the Euclidean distance of group members), depending on the level of analysis of the attribute.2 The final characteristic of organizational demography, the mechanism, refers to the process by which the attributes predict outcomes. The mechanism may be either indirect or direct.

Explanations for the effects of demography on organizational outcomes have followed several avenues, including social identity and social categorization process (Tajifel, 1974; Tajifel & Turner, 1986; Turner, 1985, 1987), the similarity-attraction paradigm (Byrne, 1971), and the degree of distinctiveness (Mullen, 1983, 1987; Thomas, Ravlin, & Wallace, 1996).

Relevant variables for assessing demographic effects in international or global organizations have included the following: (1) the number of years with the company, (2) national culture, (3) educational background, (4) gender, (5) race, and (6) age. Although all of these demographic attributes are important, some may be more salient than others when it comes to understanding individuals’ effectiveness or fit in the organization. Age, race, and gender, for example, are easily observable; tenure, education, or field of study are not. Following are highlights from past research and our thoughts on the relative importance of each demographic attribute.

Number of years with company. Most of the organizational demography studies have continued to use Pfeffer’s index, the tenure or length-of-service distribution in an organization or its top-management team, as the demographic variable of primary interest.3 Effectiveness measures examined across these studies have varied. They have included turnover, innovation, diversification, and adaptiveness (Carroll & Harrison, 1998; Tsui, Egan, & Xin, 1995).

A preponderance of evidence has shown a positive relationship between organizational tenure and increased group effectiveness. Arguments for this positive relationship have been consistent with social categorization and similarity-attraction theories (Williams & O’Reilly, 1998). According to Tsui and O’Reilly (1989), the cause of the relational demographic effects are often attributed to a combination of high-level attraction based on similar experiences, attitudes, and values (see Byrne, 1971; Byrne, Clore, & Smeaton, 1996), and strong communication among the interacting members (Roberts & O’Reilly, 1979). As tenure in organizations increases, employees gain a better understanding of policies and procedures. In general, tenure acts as an indicator of organizational experiences (Zenger & Lawrence, 1989).

It may be that executives who are similar in their length of service to the organization have gained a better understanding of the organization through their shared experiences resulting in overall effectiveness. Based on this view, our resulting hypothesis was

HYPOTHESIS 5.2: As the similarity of an individual’s organizational tenure to that of others in a group increases, the perception of that individual’s managerial effectiveness increases.

National culture. An increase in research on the impact of multicultural differences in organizational behavior has accompanied the rising number of companies expanding into international markets. Many of the studies have focused on cultural differences in terms of values, norms, and assumptions (Adler, 1991; Hofstede, 1980; Schwartz, 1994; Triandis, 1995). According to Triandis, Kurowski, and Gelfand (1994), to the extent that cultures share objective elements (such as language, religion, political systems, or economic systems) or subjective ones (values, attitudes, beliefs, norms, roles), they are considered similar. Triandis (1995) further concluded that different cultural groups have a higher chance of unification if they (a) share goals and equal status, (b) have a shared membership, (c) maintain frequent contact and a shared network, and (d) are encouraged by the organization to view each other in a positive light.

The more a person’s national culture identity is distinct from others in the workgroup, the more difficult it will be for the members of the workgroup to perceive each other as similar. One might conclude that one of the most important factors in understanding diversity in international organizations is how national culture affects social behavior. A large cultural distance may in fact make individuals more self-aware, resulting in their having difficulty adjusting and being accepted by the workgroup. Thus:

HYPOTHESIS 5.3: As the similarity of an individual’s national culture to that of others in a group increases, the perception of that individual’s managerial effectiveness increases.

Educational background. Educational achievement can be proxy for status and power within organizations. In the United States, for example, it is often assumed that senior-level people have more education than their direct reports. People believed to have different levels of education are often assumed to differ in their knowledge, skills, and abilities. It is not uncommon to find people who have similar educational backgrounds performing similar tasks within organizations.

Unlike the demographic attributes discussed previously, however, the literature has reported that increased diversity in educational background improves effectiveness (Hambrick, Cho, & Chen, 1996; Wiersema & Bantel, 1992) and in some cases communication (Glick, Miller, & Huber, 1993; Jenn, Northcraft, & Neale, 1997). Therefore,

HYPOTHESIS 5.4: As the dissimilarity of an individual’s educational attainment (college degree, for example) to that of others in a group increases, the perception of that individual’s managerial effectiveness increases.

Gender and race. There was enough support in the literature to treat gender and race effects separately. In the organizational demography literature, however, the two attributes often were examined together. Likewise, we have introduced them together in this report.

Gender and racial distinctiveness cannot be suppressed. The lack of representation of women and people of color in senior-level managerial positions has not gone unnoticed. For those who historically have been denied managerial opportunities and who have lacked clear role models from which to learn, two additional struggles were reported to have precedence. According to Ruderman and Hughes-James (1998), managing multiple identities and fitting in are particularly difficult for women and people of color as they develop their self-identities as leaders. Some research has suggested that for white women there is a limited range of acceptable behavior that is more stereotypically masculine than feminine (Morrison, White, & Van Velsor, 1992). Because of a lack of role models or coaches, people of color have to identify those acceptable behaviors themselves (Ruderman & Hughes-James, 1998).

Specific to the organizational demography literature, differences in gender and race were shown to relate negatively to psychological commitment and intent to stay, and positively to frequency in absence (Tsui, Egan, & O’Reilly, 1992). Konrad, Winter, and Gutek (1992) found that minority women were more likely to experience dissatisfaction and organizational isolation. In a more recent study, Tsui and Egan (1994) found no differences in the level of direct reports’ citizenship behaviors when they were rated by a boss of the same race. White supervisors rated nonwhite subordinates lower than white subordinates, and white subordinates were rated highest by nonwhite supervisors.

To add to the confusion of the influence of diversity on workgroups, Wharton and Baron (1987), in an investigation of the effects of occupational gender desegregation of men, found that men in mixed-gender work settings reported significantly lower levels of satisfaction and a higher level of depression than men in either female- or male-dominated work settings. Further, they found that working among mixed-gender groups may take on different meanings for men than for women. Gender self-categorization for men appeared to be more important (for men, being male is more important than being female is for women), and gender was a symbolic representation of certain occupations—such as senior management—in organizations (Tsui, Egan, & O’Reilly, 1992). Because it is likely that an international organization will have a greater distribution of diversity in its workforce, we propose the following:

HYPOTHESIS 5.5: As the similarity of an individual’s gender to that of others in a group increases, the perception of that individual’s managerial effectiveness increases.

HYPOTHESIS 5.6: As the similarity of an individual’s race to that of others in a group increases, the perception of that individual’s managerial effectiveness increases.

Age. Similarly aged employees often have common experiences outside of work, which have tended to produce employees who share similar attitudes, beliefs, and interests inside and outside of the organization (Rhodes, 1983; Zenger & Lawrence, 1989). According to Zenger and Lawrence, “the youngest employees tend to be unmarried, and slightly older employees may be newly married with young children. Middle-aged employees may be divorced and have parents who need special care, and older employees tend to look forward to quiet lives without dependents and with grandchildren” (p. 365).

Studies have shown a positive relationship between age and job satisfaction (Hunt & Saul, 1975; Kalleberg & Loscocco, 1983), age and job involvement (Saal, 1978), age and commitment (Morris & Sherman, 1981), and age, tenure, and frequency of technical communication (Zenger & Lawrence, 1989). Tsui, Egan, and Xin (1995) pointed out that many organizational demography studies have included age and tenure as independent variables to test Pfeffer’s (1983) tenure demography theory (see, for example, Bantel & Jackson, 1989; Murry, 1989; Jackson, Brett, Sessa, Julin, & Peyronnin, 1991; Tsui, Egan, & O’Reilly, 1992; Tsui & O’Reilly, 1989; Wagner, Pfeffer, & O’Reilly, 1984; Wiersema & Bantel, 1992; Zenger & Lawrence, 1989). Pfeffer argued that age and tenure distributions are not perfectly correlated and that they should be kept distinct.

In international organizations it may be that age similarity produces similarity in general attitudes about work that result in overall effectiveness. Therefore,

HYPOTHESIS 5.7: As the similarity of an individual’s age to that of others in a group increases, the perception of that individual’s managerial effectiveness increases.

Results and Discussion

The Euclidean distance formula was used to measure each individual’s dissimilarity from the group on attributes, age, sex, race, country of current residence, and native country (see Jackson et al., 1991). The Euclidian distance provides a measure of the individual’s dissimilarity from the group on each attribute individually, with possible scores for each attribute ranging from 0 (no difference from the group) to 1 (different from every member of the group). Zero-order correlations were conducted between demographic variables and effectiveness criteria.

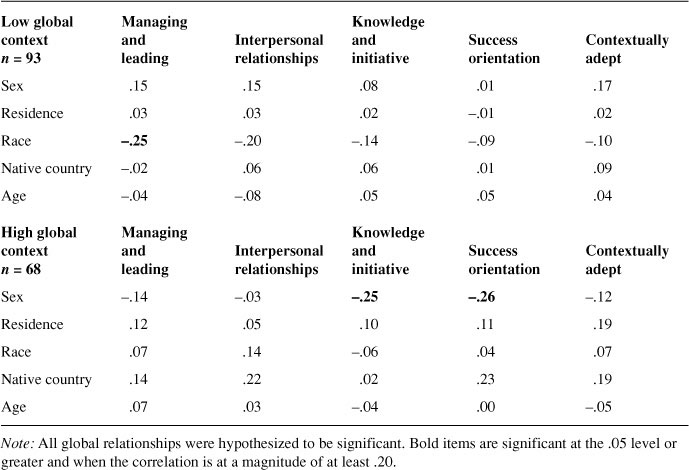

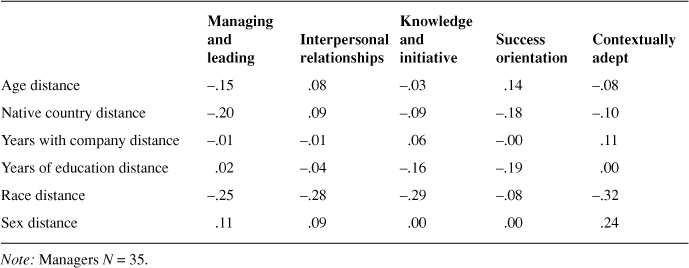

The results of the influence of experience working in heterogeneous workgroups can be seen in Table 5.1. Hypothesis 5.1 was not supported.

Table 5.1

Heterogeneity of Group in Most Recent Domestic Job Correlated with Effectiveness Ratings for Managers in Low and High Global Contexts

Previous experience working with diverse groups does not enhance managerial effectiveness as expected. There is in fact a negative relationship between boss effectiveness rating and experience managing people of a different gender in the high global condition. Because 89% of our sample was male, it is most likely females who, on the basis of gender, reported high scores on difference from others in the former workgroup. Although men and women did not receive significantly different criterion scores from bosses, there was a trend for bosses to give lower scores to women than to men. It is unclear whether this result means that if a manager has experience working with people of the opposite sex that manager is less likely to be effective in a global role, or that women are more likely to receive low scores from their bosses than are men when the work is global in scope. The same line of thought holds for the significant finding regarding race for local managers.

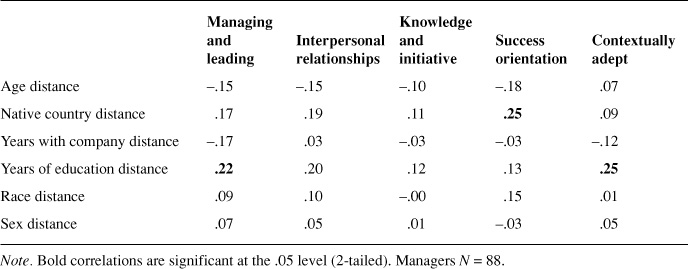

The Euclidean distance measure was also used to test the influence of organizational cohort homogeneity on perceptions of effectiveness. For this analysis, however, individuals’ demographic similarity with their cohort group (company) was examined within each participating organization. Because we framed our hypotheses in terms of similarity, we expected to find negative correlations. The results are displayed in Tables 5.2–5.5.

As shown in Table 5.2 less than half of the demographic variables were negatively correlated with bosses’ ratings of effectiveness. We did find a modest but statistically significant association between an increase in years of education distance and bosses’ ratings of individuals’ contextual adeptness and managing and leading. In other words, managers who are different from their cohort in terms of their education were perceived to be more effective on two of the five criterion measures. Another statistically significant association was found among the cohort in company A’s native country distance and success orientation. These results suggested that being dissimilar from others in terms of education and nationality may positively affect perceptions of effectiveness.

Table 5.2

Correlations Between Organizational Demographic Variables and Managerial Effectiveness for Company A

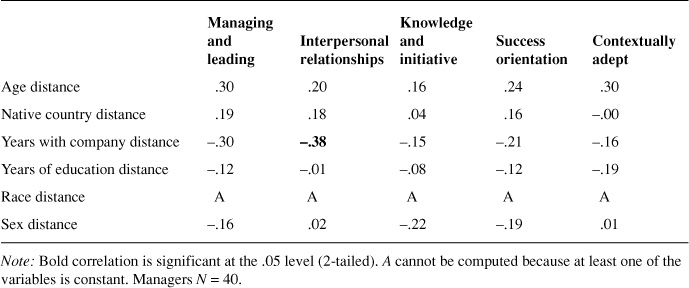

For the executive cohort in company B (Table 5.3), over half of the demographic variables were negatively correlated with bosses’ ratings of effectiveness even though these relationships were not statistically significant. We did find a modest association between an increase in years with the company distance and a decrease in bosses’ ratings of individuals’ interpersonal relationships. That is, managers in company B who were different from their cohort in the number of years they had been with the company were perceived by their bosses to have poor interpersonal relationships.

For company C, over half of the demographic variables were negatively correlated with bosses’ ratings of effectiveness, even though these relationships were not statistically significant (see Table 5.4).

Table 5.3

Correlations Between Organizational Demographic Variables and Managerial Effectiveness for Company B

Table 5.4

Correlations Between Organizational Demographic Variables and Managerial Effectiveness for Company C

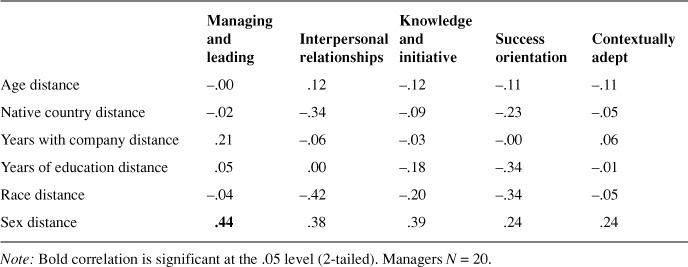

Results for the last company in our study (labeled D) showed over half of the demographic variables were negatively correlated with bosses’ ratings of effectiveness (these relationships were not statistically significant). We found one statistically significant association between an increase in sex distance and bosses’ ratings of managers’ managing and leading effectiveness. Phrased differently, as sex distance increases, perception of leadership effectiveness increases.

Table 5.5

Correlations Between Organizational Demographic Variables and Managerial Effectiveness for Company D

These results suggest that an individual’s demographic difference from his or her cohort can affect perceptions of his or her effectiveness. Comparing the results across all four companies, being unlike others in terms of education and nationality may affect perceptions of effectiveness. These data also suggest that people who have been in a job for a long time are perceived by their bosses as less effective. More obviously, those who have achieved higher educational degrees than their cohorts are perceived by their bosses as being more competent. Finally, an individual’s being different in gender from a predominantly male or female cohort increases bosses’ effectiveness ratings.

1In organizational demography, there are two ways to define the unit of analysis: individual-level similarity or dissimilarity, and unit level. The individual measure compares all members of the group to each other so that each individual receives a score. At the unit level, the whole group gets a score.

2The Euclidean distance measure computationally is the square root of the individual;s mean squared distance from the other members in the group on any demographic variable.

3The coefficient of variation in tenure has also become the most common measure of length-of-service heterogeneity. The measure is calculated as the standard deviation of tenure over the mean of tenure.