7

Board of Directors: A Powerful Instrument in Corporate Governance

CHAPTER OUTLINE

- Introduction

- Role of Board in Ensuring Corporate Governance

- Governance Issues Relating to the Board

- The Role of Directors

- Independent Directors

- Directors’ Remuneration

- Family-owned Businesses and Corporate Governance

- Some Pioneering Indian Boards

Introduction

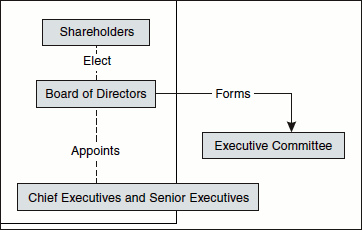

The separation of ownership from active directorship and management is an essential feature of the company form of organisation. To manage the affairs of a company, shareholders elect their representatives in accordance with the laid down policy. These representatives are called the “directors” of the company. A number of such directors constitutes the “board of directors” and that is the top administrative body of the corporation. The board may sometimes appoint an executive committee to carry on certain assigned functions under its direction. The board generally has only part-time directors.

Corporate Management Structure

The board may be expected to lay down policies, procedures and programmes, but may not be able to secure their implementation under their guidance and continuous supervision, or communicate their decision to the rest of the staff. To do this, the executive committee consisting of one or more whole-time directors and other top officials is appointed. These appointees of the board are called chief executive officers (CEOs) or managing directors, depending on how the company wants to name them. The chief executives serve as a link between the board of directors on one side, and the operating organisation on the other. Their work consists of interpreting the policy decisions for the benefit of those responsible for their execution and in dealing with the day-to-day problems of business operation. They also place important problems concerning the execution of the work assigned to them before the board and put them wise on issues involved in implementing policies. The CEOs who include managing directors and managers receive instructions from the Board and disseminate them to executives in charge of various departments. Thus, shareholders delegate a greater part of their authority as owners to the Board, which in turn, passes a substantial part of power to CEOs and they further delegate powers to departmental heads in charge of operations. This structure of corporate management is illustrated in Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1 Corporate management structure

This is the pattern that is adopted by most of the companies in India and elsewhere. From the way the corporates are structured, it can be understood that the control of management is in the hands of shareholders, the board of directors, and in some cases, chief executives to whom the board has delegated some of its powers.

Company Director and the Board

In the eyes of law, a company is an artificial person, who however, has no physical existence and has neither a body nor soul. As Cairns puts it clearly: “The company itself cannot act in its own person, for it has no person, it can only act through directors.” In the words of Lord Cranworth L.C.: “The directors are a body to who has delegated the duty of managing the general affairs of the company. A corporate body can only act by agents and it is, of course, the duty of those agents to act as best to promote the interests of the corporation whose affairs they are conducting.”

The Supreme Court of India was more lucid when it elucidated the company director relationship as follows: “A company is in some respects an institution like a state functioning under its basic constitution consisting of the Companies Act and the Memorandum of Association. The members in general meeting and the directorate are described as the two primary organs of a company comparable with the legislative and the executive organs of a parliamentary democracy, where the legislative sovereignty rests with the parliament, while the administration is left to the executive government, subject to a measure of control by parliament through its power to force a change of government. Like the government, the directors will be answerable to parliament constituted by the general meeting.”

In many countries, as in India, it is mandatory for a public limited company to have directors and in practice “the identities of directors and those of their companies are inseparable for good or bad”.” With the business units growing in size, corporate affairs becoming more and more complex, at the same time the ownership getting more scattered and dispersed, the role of directors as fiduciaries of shareholders is paramount to investor protection and enhancement of shareholder value.”1

Who is a Director?

Section 2(13) of the Companies Act defines a director as follows: “A director includes any person occupying the position of director by whatever name called. The important factor to determine whether a person is or is not a director is to refer to the nature of the office and its duties. It does not matter by what name he is called. If he performs the functions of a director, he would be termed as a director in the eyes of the law, even though he may be named differently. A director may, therefore, be defined as a person having control over the direction, conduct, management or superintendence of the affairs of a company. Again, any person in accordance with whose directions or instructions, the board of directors of a company is accustomed to act is deemed to be a director of the company.” However, though this definition seems to be comprehensive, it is vague and ambiguous to some extent. As it is pointed out by some authorities on the subject: “It is doubtful whether there are any instances in Indian corporate history where any person in a company who is not called a director is deemed or reckoned as such by virtue of his functional responsibility.”2

A director may, therefore, be defined as a person having control over the direction, conduct, management or superintendence of the affairs of a company. Again, any person in accordance with whose directions or instructions, the board of directors of a company is accustomed to act is deemed to be a director of the company.”

Section 2(6) of the Companies Act states that directors are collectively referred to as “board of directors” or simply the “board”.

Kinds of directors

A director may be a full time working director, namely, managing or whole time director covered by a service contract. Managing and whole time directors are in charge of the day-to-day conduct of the affairs of a company and are together with other team members collectively known as “management” of the company. A company may also have non-executive directors who do not have anything to do with the day-to-day management of the company. They may attend board meetings and meetings of committees of the board in which they are members. We can recognise another category of directors as per certain provisions of the Indian Companies Act—“Shadow Directors”. These so-called “deemed directors” acquire their status by virtue of their giving instructions (other than professional advices) according to which “appointed” directors are accustomed to act.3

Directors’ Appointment

The Articles of Association of a company usually name the first set of directors by their respective names or prescribe the method of appointing them. If the first set of directors are not named in the Articles, the number and the names of directors shall be determined in writing by the subscribers of the Memorandum of Association or a majority of them. If the first set of directors are not appointed in the above manner, the subscribers of the Memorandum who are individuals become directors of the company. They shall hold office until directors are duly appointed in the first general meeting. Certain provisions of the Companies Act in India govern the appointment or reappointment of directors by a company in general meeting.

Legal Position of a Director

It is rather difficult to define the exact legal position of the directors of a company. They have been described variously as agents, trustees, or managing partners of the company, but “such expressions are not used as exhaustive of the powers and responsibilities of such persons but only as indicating useful points of view from which they may for the moment and for the particular purpose be considered”.4 The legal position of directors as agents and trustees emanate from the fact that a company being an artificial person cannot act in its own person. It can act only through the directors who become their agents in the transactions the company makes with others. Likewise, directors are deemed to be trustees of a company’s money and properties. It has become a well-established fact now that directors are not only agents but also act as trustees, as a result of several court decisions in India and England.

Duties and Responsibilities of Directors

Directors have certain duties to discharge such as: (i) fiduciary duties (ii) duties of care, skill and diligence; (iii) duties to attend board meetings; (iv) duties not to delegate their functions except to the extent authorised by the Act or the constitution of a company and to disclose his interest.

With regard to fiduciaries, directors must (a) exercise their powers honestly and bona fide for the benefit of the company as a whole and (b) not to place themselves in a position in which there is a conflict between their duties to the company and their personal interests. They must not make any secret profit out of their position. Further, the fiduciary duties of directors are owed to the company and not to individual shareholders. Of these four, the first two duties need elucidation. Directors should carry out their duties with reasonable care and exercise such degree of skill and diligence as is reasonably expected of persons of their knowledge and status. However, a director is not bound to bring any special qualification to his office, as for instance, the director of a medical insurance company is not expected to have the expertise of an actuary or the skills of a physician. But if a director fails to exercise due care and diligence expected of him, he is guilty of negligence. The standard of care, skill and diligence depends upon the nature of the company’s business and circumstances of the case. Factors such as the type and nature of work, the division of powers between directors and other executives, general usages, customs and conventions in the line of business in which the company is engaged and whether directors work gratuitously or for a remuneration will have an impact on the standards of care and diligence expected of the directors.

Directors have certain duties to discharge such as: (i) fiduciary duties (ii) duties of care, skill and diligence; (iii) duties to attend board meetings; (iv) duties not to delegate their functions except to the extent authorised by the Act or the constitution of a company and to disclose his interest. Factors such as the type and nature of work, the division of powers between directors and other executives, general usages, customs and conventions in the line of business and whether directors work gratuitously or for a remuneration will have an impact on the standards of care and diligence expected of the directors.

Qualifications and Disqualifications of Directors

To be appointed as a director of a company, public authorities prescribe some qualifications. “No corporate, association or firm can be appointed as director of a company.” A director must (a) be an individual; (b) be competent to enter into a contract and (c) hold a share qualification if so required by the Articles of Association. As there are qualifications for being a director, there are some disqualifications too.

The following persons are disqualified for appointment as director of a company: (i) A person of unsound mind, (ii) an undischarged insolvent or one whose petition for declaring himself so is pending in a Court, (iii) a person who has been convicted by a Court for any offence involving moral turpitude, (iv) a person whose calls in respect of shares of the company are held for more than 6 months have been in arrears; and (v) a person who is disqualified for appointment as director by an order of the Court on grounds of fraud or misfeasance in relation to the company. And, of course, directors can be removed from office by (i) the shareholders, (ii) the Central (Federal) Government and (iii) the Company Law Board.

The Board of Directors

The board of directors of a company which includes all directors elected by shareholders to represent their interests is vested with the powers of management. The board has extensive powers to manage a company, delegate its power and authority to executives and carry on all activities to promote the interests of the company and its shareholders, subject to certain restrctions imposed by public authorities.

The board of directors of a company is authorised to exercise such powers and to perform all such acts and things as the company is entitled to. This means that the powers of the board of directors is co-extensive with those of the company subject to two conditions: (i) the board shall not do any act which is to be done by the company in general meeting of shareholders and (ii) the board shall exercise its powers subject to the provisions contained in the Ariticles or the Memorandum or in the Federal Acts concerned with companies or any regulation made by the company in any general meeting. But no regulation made by company in general meeting shall invalidate any prior act of the board which would have been valid if the regulation had not been made.

Powers of the Board

Under Section 292 of the Companies Act, it is stipulated that a company’s board of directors shall exercise the follwing powers on behalf of the company by means of resolutions passed at the meeting of the board: (a) make calls on shareholders in respect of money unpaid on their shares, (b) issue debentures, (c) borrow money otherwise (for example, through public deposits), (d) invest the funds of the company, and (e) make loans.

Furthermore, there are certain other powers specified by the Companies Act under various sections which shall be exercised by the board of directors only at the meeting of the board. These powers include: (a) to fill vacancies in the board; (b) to sanction or give assent for certain contracts in which particular directors, their relatives and firms are interested; (c) to receive notice of disclosure of directors’ interest in any contract or arrangement with the company; (d) to receive notice of disclosure of shareholdings of directors; (e) to appoint as managing director or manager a person who is already holding such a post in another company and (f) to make investments in companies in the same group.

Every resolution delegating the power to borrow money other than debentures shall specify the total amount outstanding at any time up to which money may be borrowed by the delegate. Likewise, every resolution delegating the power to invest the funds of the company shall specify (a) the total amount up to which the funds may be invested and (b) the nature of the investments which may be made by the delegate. So, every resolution delegating the power to make loans shall specify: (a) the total amount upto which loans may be made by the delegate; (b) the purposes for which the loans may be made and (c) the maximum amount of loans which may be made for each such purpose in individual cases.

However, the general meeting of shareholders is competent to intervene and act in respect of a matter delegated to the board of directors in cases where (i) the directors act mala fide; (ii) the directors themselves are wrongdoers; (iii) the board as a whole is found to be incompetent, when for instance, all directors are interested in a transaction with the company; (iv) there is a deadlock in management and (v) there is a fit case for the shareholders to exercise their residuary powers.

The board of directors can also exercise certain other powers as listed below with the consent of the company in general meeting, as in the case of an amalgamation scheme:

- To sell, lease or otherwise dispose of the whole or substantially the whole of the undertaking of the company.

- To remit or give time for repayment of any debt due to the company by a director except in the case of renewal or continuance of an advance made by the banking company to its director in the ordinary course of business.

- To borrow in excess of capital.

- To contribute to charitable and other funds not relating to the business of the company or the welfare of its employees beyond a specified amount.

- To invest compensation amounts received on compulsory acquisition of any of the company’s properties.

- To appoint a sole selling agent.

The above provisions regarding the powers of the board of directors are applicable subject to any restriction contained in the Articles of Association and spcific agreements.The powers of the board are to be exercised in the best interests of the company. It should always be ensured that in the exercise of these powers, the company’s interest is kept above the self-interests of the directors.

Nominee Directors

A nominee director is generally appointed in a company to ensure that the affairs of the company are conducted in a manner dictated by the laws governing companies and to ensure good corporate governance. A nominee director, as an affiliated director, is nominated to ensure that the interests of the institution which he or she represents are duly or effectively safeguarded. In India, the Companies Act does not distinguish between other directors and a nominee director with regard to liabilites for violations of laws by companies. In the case of a nominee director appointed to represent a financial institution in an assisted company, normally the statute governing the concerned financial institution contains special provisions in this connection. For instance, Section 27 of the State Financial Corporations Act seeks to empower the concerned financial institution to appoint nominee directors on the boards of assisted companies and grants immunity to such directors from liabilities for the company’s defaults and contraventions.“Such appiontments are valid and effective notwithstanding anything to the contrary contained in the Companies Act, 1956, or in any other law for the time being in force or in the Memorandum or the Articles of Association or any other instrument relating to an industrial concern.”5 The terms of appointment, number of such directors, their removal from office, their substitution by others are all matters to be decided by the financial institution concerned. In this context, it is pertinent to note that in India, in the numerous instances of corporate frauds which came to light, the concerned company boards did have one or two nominee directors who could have, had they done their duties and carried out their responsibilities, prevented the misdeeds of the companies and their errant directors, and could have saved the poor shareholders’ hard-earned money. The nominee directors did nothing to stop the frauds and yet they could not be proceeded against because of the immunity they enjoyed.

A nominee director is generally appointed in a company to ensure that the affairs of the company are conducted in a manner dictated by the laws governing companies and to ensure good corporate governance. A nominee director, as an affiliated director, is nominated to ensure that the interests of the institution which he or she represents are duly or effectively safeguarded. In India, the Companies Act does not distinguish between other directors and a nominee director with regard to liabilites for violations of laws by companies.

To prevent such an unsavoury situation from arising, the SEBI-appointed Kumar Mangalam Birla Committee on corporate governance suggested that financial institutions should not have their representatives on the boards of assisted companies. This would not only prevent their involvement in such mismanaged companies, but also can avoid the unpleasant situation of their being privy to unpublished, price-sensitive information. Otherwise, it could easily expose these institutions and their nominess to charges of insider trading when they deal in the securities of such companies. Though there is a strong case for a lending institution to have a nominee on board of a company as a creditor to protect their interests, their direct involvement would implicitly mean that the nominee directors share equal responsibility for wrong decisions as any other director of the company.

Liabilities of Directors

Directors of a company may be held liable under the following situations:

- Directors of a company may be liable to third parties in connection with the issue of a prospectus, which does not contain the particulars required under the Companies Act or which contains material misrepresentations;

- Directors may also incur personal liability under the Act on the following conditions:

- On their failure to repay application money if minimum subscription has not been subscribed.

- On an irregular allotment of shares to an allottee (and likewise to the company) if loss or damage is sustained.

- On their failure to repay application money if the application for the securities to be dealt in on a recognised stock exchange is not made or refused and

- On failure by the company to pay a bill of exchange, hundi, promissory note, cheque or order for money or goods wherein the name of the company is not mentioned in legible characters.

The directors responsible for fraudulent trading on the part of the company may, by an order of the Court, be made personally liable for the debts or liabilities of the company at the time of its winding up.

- Apart from the liability of the director under the Companies Act, he or she has certain other liabilities which are independent of the Act. Though a director as an agent of the company, he is not personally liable on contracts entered into on behalf of the company, there could be some exceptional circumstances that may make him liable. For instance, (i) by signing a negotiable instrument without the company’s name and the fact that he is signing on behalf of the company, he is personally liable to the holder of such an instrument; ii besides, if a director enters into a contract, which is ultra vires the Articles of the company, the director is personally liable for breach of implied warranty of authority; (iii) any director who personally committed a fraud or any other tort in the course of his duties is liable to the injured party. The contract of agency or service cannot impose any obligation on the agent or servant to commit, or assist in the committing of fraud or any other illegality. The company also be held liable, but it does not exonerate the concerned director.

Directors of a company may be held liable (i) to third parties in connection with the issue of a prospectus, which does not contain the particulars required under the Companies Act or which contains material misrepresentations; (ii) under the act on the following conditions: (a) On their failure to repay application money of minimum subscription has not been subscribed. (b) On an irregular allotment of shares to an allottee if loss or damage is sustained. (c) On their failure to repay application money if the application for the securities to be dealt in on a recognised stock exchange is not made or refused, and (d) On failure by the company to pay for goods wherein the name of the company is not mentioned legibly.

The Directors’ Liability to the Company

Directors are also liable to the company under the following heads: (1) ultra vires acts, (2) negligence, (3) breach of trust and (4) misfeasance.

- Ultra vires acts: Directors are personally liable to the company in matters of illegal acts. For instance, if directors pay dividends out of capital or when they dissipate the funds of the company in ultra vires transactons, they are jointly and severally liable.

- Negligence: A director may be held liable for negligence in the exercise of his duties. Though there is no statutory definition of negligence, if a director has not shown due care and diligence, then he is considered negligent. However, it is essential in an action for negligence the company has suffered some damage. Negligence without damage or damage without negligence is not actionable.

- Breach of trust: Since the directors of a company are trustees of its money and property, they must discharge their duties in that spirit to the best interest of the company. They are liable to the company for any material loss on account of the breach of trust. Likewise, they are also accountable to the company for any secret profits they might have made in transactions carried out on behalf of the company.

- Misfeasance: Directors are liable to the company for misfeasance, i.e. wilful misconduct. For this purpose they may be sued in a Court of Law.

Directors are also liable to the company under the following heads: (1) ultra vires acts, (2) negligence, (3) breach of trust and (4) misfeasance. Directors should carry out several statutory duties most of which relate to the maintenance of proper accounts, filing of returns or observance of certain statutory formalities. If they fail to perform these duties, they render themselves liable to penalties.

Liability for Breach of Statutory Duties

Directors should carry out several statutory duties most of which relate to the maintenance of proper accounts, filing of returns or observance of certain statutory formalities. If they fail to perform these duties, they render themselves liable to penalties.

The Companies Act imposes penalty upon directors for not complying with or contravening the provisions of the Act, which include sections on criminal liability for mis-statements in prospectus, penalty for fraudulently inducing persons to invest money, purchase by a company of its own shares, concealment of names of creditors entitled to object to reduction of capital, penatly for default in filing with the Registrar for registration of the particulars of any change created by the company. In all these sections, the person, sought to be made liable is described as an “officer who is in default”. The expression “officer in default” includes a director also.

Liability for Acts of His Co-directors

A director is not liable for the acts of his co-directors provided he has no knowledge and he is not a party to it. His co-directors are not his servants or agents who can by their acts impose liability on him. Likewise, if a director is fraudulent, his co-directors are not liable for not discovering his fraud in the absence of circumstances to arouse their suspicion.

Moreover, when more than one director is alleged to have neglected his duties of care, all the directors are jointly and severally liable. If an action is brought by the company against only one of them, he is entitled to contribution from other directors.

Power of Court to Grant Relief

The Companies Act provides under Section 633 the following reliefs to a director: In a proceeding for negligence, default, breach of duty, misfeasance or breach of trust against an officer of a company, it might appear to the court that the officer has acted honestly and reasonably and that having regard to all circumstances of the case, he ought fairly to be excused. In such a case, the court may relieve him, either wholly or partly, from his liability.

The Companies Act provides under Section 633 the following reliefs to a director: In a proceeding for negligence, default, breach of duty, misfeasance or breach of trust against an officer of a company, it might appear to the court that the officer has acted honestly and reasonably and that having regard to all circumstances of the case, he ought fairly to be excused. In such a case, the court may relieve him, either wholly or partly, from his liability.

The object of Section 633 is to provide relief against undue hardship in deserving cases. But for getting relief under Section 633, it must be proved by the officer concerned that; (a) he acted honestly, (b) he acted reasonably and (c) having regard to all circumstances of the case, he ought fairly to be excused.

However, the granting of relief under Section 633 is discretionary. It may be partial or complete or on certain terms or unconditional. But in a criminal proceeding under Section. 633 in respect of negligence, default, breach of duty, misfeasance or breach of trust, the Court shall have no power to grant relief from any civil liability which may attach to the officer concerned in respect of such negligence, default, etc.

Directors with Unlimited Liability

In a limited company, the liability of all or any of the directors may, if so provided by the Memorandum be unlimited. Likewise, the liability of the manager may also be unlimited. In such a company, the directors and the manager of the company and the person who proposes a person for appointment to any of these offices shall add to the proposal that liability of such person will be unlimited. Before such a person accepts the office, notice in writing that his liability will be unlimited shall be given to him.

If the Memorandum does not contain any provision making the liability of all or any of its directors and manager unlimited, the company may, if so authorised by its Articles and by a special resolution, alter its Memorandum so as to render unlimited liability of any of these personnel. Upon the passing of the special resolution, it shall be deemed as if the provision had been originally contained in the Memorandum. An alteration making the liability of these personnel unlimited shall become effective against the personnel only on the expiry of his existing term, unless he has given his consent to his liability becoming unlimited.

Public Examination of Directors

In case of winding up of a company by the Court, the Official Liquidator may make a report to the Court stating that in his opinion, a fraud has been committed

- by any person in the promotion or formation of the company.

- by any officer of the company in relation to the company, since its formation.

In such a case, the Court may, after considering the report, direct that the person or officer shall

- attend before the Court on a day appointed by it for that purpose, and

- be publicly examined (i) as to the promotion or formation or the conduct of the business of the company, or (ii) as to his conduct and dealings as an officer thereof.

Validity of Acts of Directors

Acts done by a person as director shall be valid, notwithstanding that it may afterwards be discovered that his appiontment was invalid by reason of any defect or disqualification or had terminated by virtue of any provision contained in the Articles. But, acts done by a director after appointment has been shown to the company to be invalid or to have terminated shall not be valid.

The effect of these provisions is to validate the acts of a director who has not been validly appointed because there was some slip or irregularity in his appointment. Where there is no real appointment at all, the acts of the person acting as director shall not be validated. The acts of the invalidly appointed director shall be valid only when the board of directors acts bona fide and some defect which can be cured later comes to light.

Section 290 of the Companies Act does not validate the acts which could not have been done even by a properly appointed director or the acts of a director who knows of the irregularity of his appointment.

Further, the provisions of Section 290 declaring acts of a director to be valid notwithstanding the subsequent discovery of a defect or disqulifiaction in him give protection only to acts of directors which are otherwise not illegal and do not apply to invalid resolution passed in a meeting not properly convened. Benefit of Section 290 can normally be taken by third parties and not by the directors or their close relations.

De Facto and De Jure Directors

A director who is not duly appointed but acts as a director is known as a facto’ director and is as much liable as a ‘de jure’ (appointed as per law) director. Thus, as between a company and third person a ‘de facto’ director is a ‘de jure’ director.

Disablities of Directors

In order to protect the interest of a company and its shareholders, the Companies Act has placed the following disabilities on the directors:

The Companies Act has placed the following disabilities on the directors: (i) Any provision in the Articles or an agreement which exempts a director from any liability on account of any negligence, default, misfeasance, breach of duty or breach of trust by him shall be wholly void. (ii) An undischarged insolvent shall not be appointed to act as director of any company. (iii) No person shall hold office as director in more than 15 companies. (iv) A company shall not, without due approvals make any loan to any director of the lending company or of a company which is its holding company or a partner or relative of such a director.

- Any provision in the Articles or an agreement which exempts a director (including any officer of the company or an auditor) from any liability on account of any negligence, default, misfeasance, breach of duty or breach of trust by him shall be wholly void.

- An undischarged insolvent shall not be appointed to act as director of any company or in any way to take part in the management of any company.

- No person shall hold office at the same time as director in more than 15 companies.

- A company shall not, without obtaining the previous approval of the central government in that behalf, directly or indirectly make any loan to (i) any director of the lending company or of a company which is its holding company or a partner or relative of such a director, (ii) a firm in which such a director or relative is a partner, (iii) a private company of which such a director is a director or member, (iv) a body corporate at a general meeting of which not less than 25 per cent of the total voting power may be exercised or controlled by such a director; or (v) a body corporate, the board of directors, managing director, or manager whereof is accustomed to act in accordance with the directions or instructions of the Board, or of a director or directors of the lending company.

- Except with the consent of the board of directors of a company, a director of the company or his relative, a firm in which such a director or relative is a partner, any other partner, in such a firm, or a private company of which the director is a member or director, shall not enter into any contract with the company (a) for the sale, purchase or supply of goods, materials or services or (b) for underwriting the subscription of shares in, or debentures of, the company.

Further, in the case of a company having a paid-up share capital of not less than Rs. 1 crore, no such contract shall be entered into except with the previous approval of the central government.

- A director shall not assign his office. If he does, the assignment shall be void.

- The following persons shall not hold any office or place of profit in a company except with the consent of the company accorded by a special resolution: (i) director of the company, (ii) (a) a partner or relative of such a director, (b) firm in which such a director or his relative is a partner, (c) private company of which such a director is a director or member or a director or manager of such a company if the office of profit carries a total monthly remuneration of such sum as may be prescribed.

However, an appointment of the above persons can be made as managing director, manager, banker or trustee for the debenture-holders of the company (a) under the company or (b) under a subsidiary of the company if the remuneration received from such subsidiary in respect of such office or place of profit is paid over to the company or its holding company.

Special resolution is necessary for every appointment in the first instance and every subsequent appointment. It is sufficient if the special resolution according to the consent of the company is passed at a general meeting of the company held for the first time after holding of such office or place of profit.

The appointment of the following persons to a place of profit in the company, which carries a monthly remuneration of not less than such sum as may be prescribed from time to time shall be made only with the prior consent of the company by a special resolution and the approval of the central government: (a) partner or relative of a director or manager; (b) firm in which such a director or manager, or relative or either, is a partner; (c) private company of which such a director or manager, or relative or either, is a director or member.

Every individual, firm, private company or other body corporate proposed to be appointed to an office or place of profit under the company, shall, before or at the time of such appointment, declare in writing whether he is or is not concerned with a director of the company in any of the ways referred to above.

If an office or place of profit is held without the prior consent of the company by a special resolution and the approval of the central government, the partner, relative, firm or private company shall be liable to refund to the company any remuneration or other benefit received. The company shall not waive of any sum refundable unless permitted to do so by the central government.

If any party holds an office of profit under the company in contravention of the above provisions, he has or it is deemed to have vacated his office and is also liable to refund to the company any remuneration received. The company shall not waive of recovery of any sum refundable to it unless permitted to do so by the central government.

The following persons shall not, hold any office except with the consent of the company accorded by a special resolution: (i) director of the company, (ii) (a) a partner or relative of such a director, (b) firm in which such a director or his relative is a partner, (c) private company of which such a director is a director or member or a director or manager of such a company if the office of profit carries a total monthly remuneration of such sum as may be

Prevention of Management by Undesirable Persons

The Companies Act lays down special provisions for preventing the management of companies by certain undesirable persons. Sections 202 and 203 of the Act specifically provide that these persons cannot manage a company or take part in its promotion or formation: An undischarged insolvent cannot (i) act as, or discharge any of the function of, a director or manager of any company, or (ii) directly or indirectly take part or be concerned in the promotion, formation or management of a company.

If the undischarged insolvent discharges any of the aforesaid function, he shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to 2 years, or with fine which may extend to Rs. 5,000, or both.

The expression “company” in Section 202 includes (a) an unregistered company and (b) a foreign company which has an established place of business in India.

Fraudulent Persons

Section 203 of the Companies Act gives power to the court to restrain fraudulent persons from managing companies. According to it, the court may issue an order that any of the following persons shall not, without its consent, act as a director, or take part in the promotion, formation or management of a company for a period not exceeding 5 years: (1) a person who is convicted of any offence in connection with the promotion or management of a company or (2) a person who in the course of winding up of a company (i) has been guilty of fraudulent conduct of business or (ii) has otherwise been guilty, while being an officer of the company, of any fraud or misfeasance in relation to the company or of any breach of his duty to the company.

Effectiveness of the Board of Directors

Though the board is recognised legally as the top layer of management with the responsibility of governing the enterprise, yet, in actual practice, the board of directors delegates most of its managerial power to chief executives—say, the managing director or manager. In many cases, the board appoints many committees and clothes them with its power. The most common is the executive committee though there may be other committees connected with various phases of management. However, these committees cannot make radical changes in the policy of the company. In recent years, the board of directors has come to rely more and more on the chief executives for the management of the company. The chief executives, being wholetime officers of the company, naturally devote greater time and attention to the matters connected with the management of the company. Their continuous and close contact with the operation of the company places them in a far more advantageous position in respect of the management of the company’s affairs than the board which meets only occasionally. As Newmen puts it: “It is the full-time executive who must carry the responsibility for the basic exploration and analysis of present and future problems.”

The board is recognised legally as the top layer of management with the responsibility of governing the enterprise, yet, in actual practice, the board of directors delegates most of its managerial power to chief executives.

Under the present arrangements, after a thorough and detailed study of the problems and circumstances, chief executives formulate objectives and policies and take important managerial decisions. The realistic functions of the board may, therefore, be enumerated as follows:

- Confirming management decisions on major changes in objectives, policies, and those transactions which will have a substantial effect on the success of the company.

- Providing constructive advice to the executives through discussion on important matters such as business outlook, new government legislation, wage policy, etc. with a view to guiding executives when the policies are still in the process of formation.

- Selecting chief executives and confirming the selection of other executives in the company made by chief executives.

- Reviewing the results of the company’s current operations.

Thus, as per the current practice, the initiative in the management of companies has passed into the hands of chief executives. Peter Drucker, while discussing this issue, remarks thus: “In reality, the board as conceived by the lawmakers is at best a tired fiction. It is perhaps not too much to say that it has become a shadow king.” This should not be taken to mean that the board has no important function to perform. As it is, the ultimate responsibility under the present set-up of company management rests with the board of directors. It has, therfore, to perform the important function of approving the company’s objectives and policies, of looking critically at the “profit planning” of the company, of acting as an arbiter and judge in regard to organisational problems and of keeping its hand on the pulse of the company. To quote Drucker again: “It is an organ of review, of appraisal, of appeal. Only in crisis, it becomes an organ of action.”

That the top executives carry out a good deal of homework for the benefit of the board of directors, is indeed an encouraging sign particularly in view of the increasing complexity of company operations and the other preoccupations of company directors. However, problems can arise if the board were to become a mere rubber stamp. Particularly, when company management is dominated by bureaucrats who cannot take a detached and objective view of company operation because they are too much involved with them.

Even more serious is the problem of the board of directors not acting as free agents in the discharge of their duties. For too long in India, managing agents controlled the boards of directors of companies and used them as mere tools. Even after the abolition of the managing agency system, there is a danger of their being pressurised by corporate groups and big industrial houses. It is only through democratically elected boards consisting of professional men of deep insight into business affairs that the state of company management can be improved.

Role of the Board in Ensuring Corporate Governance

Role of the Board

The clear message from the series of corporate debacles that occurred in America and several parts of the world, was simple that the board of directors is increasingly being recognised as a critical success factor for corporations, be they large or small, private or public. This understanding and appreciation of the role of the boards as being valuable has resulted in several recommendations to boost their contributions to success of companies by innumerable committees that have been appointed by governments and public spirited organisations all over the world.

Company laws enacted by various countries stress that the duty of a statutory board is to protect and represent the interests of shareholders, work out business strategy and address big issues, ensure that the management works in the best interests of the corporation and the shareholders to enhance corporate economic value.

Company laws enacted by various countries make it a point to stress that the duty of a statutory board is to protect and represent the interests of shareholders. The board cannot and does not run the company. There are executives who run the day-to-day affairs of the company as dictated by the board. The role of the board is to work out business strategy and address big issues. A board’s role is evolved from law, custom, tradition and current practice, while it gets its authority from the shareholders as their representatives to run the company’s mission. It is the broader responsibility of the board to ensure that the management works in the best interests of the corporation and the shareholders to enhance corporate economic value.

It is now clearly understood that no set of systems with a checklist and the laws of state governing them can ever ensure good governance. The quality of directors, their competence, commitment, willingness and ability to assume a high degree of obligation to the company and its shareholders as members of the board alone drives the value of any board. A strategic board with broad governing responsibilities rather than one that acts in response to the demands of the CEO has become the need of an intensely competitive world. To strengthen their position and capacity to guide the company and protect the long-term shareholder’s value, many big corporates are turning to advisory boards to draw on the collective wisdom of several professionals. All of these decisions will, of course, depend on the policy, its critical needs and long time goal of the company.

Susan F. Shultz, founder of SSA Executive Search International, author of several best sellers on the subject and a member of several boards of directors condenses her experiences and research in the following summation.6

How can a strategic board ensure good governance?

If the board is smaller, the director’s involvement will be greater.

Independence is the essence of strategic boards.

Diversity (of board) means that a company has access to the best. It also means that the company is not arbitrarily limited to a single subset of its global constituency.

If the board is not informed appropriately, intelligently and comprehensively, it cannot function. In simple words, the output is only as good as the input.

The board has a broader responsibility to long-term shareholder value than the CEO, who is necessarily focussed on day-to-day operations.

The above chart summarises how a strategic board can be built to ensure better governance practices.

1. Small size of the board: The smaller the size of the board, the greater will be the involvement of its members. This will lead to a more cohesive functioning and decision-making could be expedited, all of which will add to the efficiency of the organisation.

2. Independence of the board: Independence should be the essence of strategic boards. To achieve this end, it is advisable to have less number of insiders and more of outsiders. As Susan F. Shultz points out, this kind of composition of the board will add to the “proactiveness of the company’s board. Further, an insider’s allegiance is likely to be to his or her boss and not necessarily to the company’s shareholders. Another downside to an insider dominated board is that not only can the CEO intimidate insiders, but insiders can also inhibit the CEO”.7 Managements have a vested interest to prefer insiders as directors to the board as they are likely to continue the status quo in policies and procedures that they themselves have helped to create and retain the present senior managers.

3. Diversity of the board: It is of great importance that the board is composed of members with varied experience and expertise and diverse professional qualifications, but also of people with different ethnic and cultural backgrounds. “With markets in general, and shareholders in particular becoming active in governance issues, the pressures are intensifying on companies to diversify and broaden board membership. And thankfully, the phenomenon is not restricted to just the US and UK, this increased activism is forcing companies worldwide to reform their boards in tune with the rapid globalisation of businesses.”8

In India, for instance, with the Cadbury Committee Report and worldwide interest on corporate governance issues, several scams that have highlighted regulator’s failures on this front, have brought to the centrestage the importance of the board of directors with a sizeable number of non-executive directors.

4. A well-informed board: It goes without saying that the effectiveness and efficiency of the board of directors depends on the intelligent, timely and accurate information it gets from the management. The information they get should be appropriate and comprehensive. Various committees on corporate governance have recommended that even non-executive, independent directors should have access to a free flow of information on various issues in which they are called upon to decide. They should be allowed to have professional advice, if needs be, and the cost of it should be borne by the company.

5. The board should have a longer vision and broader responsibility: The very objective and the composition of the board dictate the need for a broader responsibility and longer vision than those of chief executives. The CEO has a specific and focussed mission of running the enterprise as a profitable one by concentrating on its day-to-day transactions. While the concerns of the CEO will centre around his immediate tasks on hand to enable a company solve its problems and tackle issues that would lead to the profitability of the firm during a financial year, the board, especially when it is composed of several outside directors, will work out long term strategies, take investment decisions and such other policy perspectives that would ensure not only the secular interests of the firm, but also of all its stockholders.

Governance Issues Relating to the Board

There are several vexed issues relating to the board of directors that are being hotly debated on several fora on corporate governance. Though these issues have generated a series of on-going discussions on familiar lines and the final verdicts have yet to be pronounced, there are certain common perceptions that have arisen which find general acceptance. These are discussed in the following pages:

Board of Directors and Corporate Governance

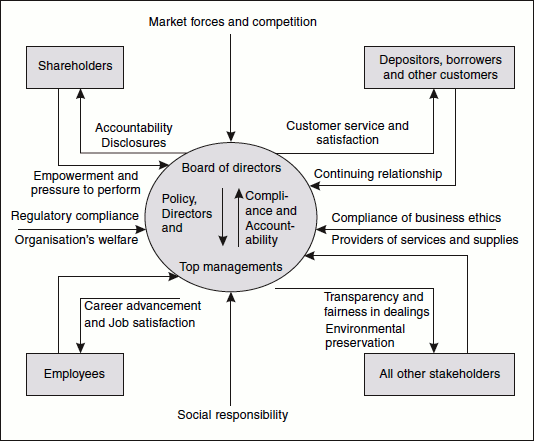

There is an increasing awareness that corporates owe their existence to shareholders and the long-term sustainability of companies depends on winning their confidence through disclosures and transparency in operations and accountability for their actions to them. This is achieved through voluntary actions on the part of board of directors and through regulatory framework such as stock exchanges, securities and exchange board and other regulatory bodies. These principles are codified as principles of corporate governance. The following diagram clearly illustrates how board of directors and top management are placed in the structure of corporates to interface, interact and intervene, when necessary, to carry on the running of the company efficiently.

Corporates owe their existence to shareholders and the long-term sustainability of companies depends on winning their confidence through disclosures and transparency in operations and accountability for their actions to them. These principles are codified as principles of corporate governance.

Figure 7.2 Role of the board in the dynamics of corporate governance

The Role of Directors

As discussed earlier, the board has to shoulder a larger responsibility than the CEO, whose role is limited to being actively engaged with routine management functions. However, “There are many boards that overlook more than they oversee”. This is more so in family-owned enterprises which are common in Asia and Latin America. In India, for instance, it is common to find family-owned concerns being run by promoters as their personal fiefdoms.Though their investments may be meagre, they manage the firms, holding positions of CEOs, managing directors, chairmen and menbers of the board of directors. In such a set-up, the board acts more like a rubber stamp, rather than shouldering large responsibilities. For better governance, the board should function as follows:

The board should for better governance ensure: directors should exhibit total commitment to the company; directors should steer discussions properly; directors should make clear their stand on issues; directors’ responsibility to ensure efficient CEOs; challenges posed by decisions on acquisitions; a board should anticipate business events; and directors should have longterm focus and stakeholder interests.

1. Directors should exhibit total commitment to the company: An efficient and independent board should be conscious of protecting the interests of all stakeholders and not concerned too much with the current price of the stock. According to Roz Ridgway, the hallmark of a good director is that he or she attends and actively participates in the meetings. This requires a cent percent commitment.

2. Directors should steer discussions properly: Another important function of the director is to set priorities and to ensure that these are acted upon. The directors should see that all important issues concerning the company’s business are discussed and decision taken, and nothing trivial dominates and bogs them down. A good director rarely dominates or hijacks the discussion to his line of thinking, but steps in when the discussion needs to be directed or adds newer thoughts after letting others have their say.

3. Directors should make clear their stand on issues: A director is also expected to have the courage of conviction to disagree. A good, responsible and duty-bound director should be willing to register dissent, when and where needed. The management led by the CEO should know that they are being challenged, should be kept on alert and should not take things for granted. Directors should also be alert to any deteriorating situations in functional areas of finance, stock market, sales, personnel, and especially those relating to moral issues.

4. Directors’ responsibility to ensure efficient CEOs: Directors have great responsibility in the matter of employment and dismissal of the CEO. The board as a whole, should recruit the best CEO they can probably hire, based on antecedents and market reports, evaluate objectively on a continuing basis his or her implementing effectively or otherwise the strategic planning devised by the board. “Great boards are those which proactively govern, help avoid the big mistakes, strategies and most importantly the best leadership is in place with the resources to lead”.9

5. Challenges posed by decisions on acquistions: One of the toughest challenges confronted by boards arises while approving acquisitions. It so happens in most cases that the board takes up the issue of acquisition only when the process has been set in motion and substantially gone through by the management. It will lead to a terrible embarrassment both to the CEO and the board, if the half-way-gone-through proposal has to be shelved. More of these none-too-worthy proposed acquisitions have to be accepted because of these predicaments.

6. A Board should anticipate business events: An efficient board should be able to anticipate business events that would spell success or lead to disaster if proper measures are not adopted in time. The directors should be alert to such ensuing situations and be ready with the strategy to meet them so that either way the company stands to gain.

7. Directors should have long-term focus and stakeholder interests: Directors have a duty to act bona fide for the benefit of the company as a whole. This duty is owed to the company, that is, the separate legal person that incorporation brings into existence, and not to any individual or group of individuals. This would imply, as per the current laws, that directors are required to act in the interests of shareholders, but at the same time, to consider such interests with a long time focus. They ought to help build productive relationships between the company and its employees, customers and suppliers, or any other kind of invesment that would serve the long term interests of its shareholders.

8. Promoting overall interests of the company and its stakeholders are of paramount importance: In recent times, those who advocate reform of laws governing corporate practices stress the importance of reformulation of the concepts behind these laws. For instance, John Parkinson in his article “Reforming Directors’ Duties” opines that while accepting that directors should not be required to do anything that would be contrary to the interest of shareholders, stresses that these interests should be understood as long term ones. This reformulation of the concept should encourage managers to pay great attention to the relationships that are the source of long term value. Once this becomes accepted, it will be logically consistent for the directors to exercise their powers in order to promote the success of the company as a business enterprise. By doing so, they shall have regard to the interests of shareholders, employees, creditors, customers and suppliers. Stretched further, it would become imperative that directors guide the company to be a socially responsible organisation. Social responsibility in this context should be seen as a means of not only compensating the society for anti-social corporate behaviour such as causing ecological damages, making money at the cost of patients by launching fully untested medicines, etc. but also for making use of the resources created by the society such as trained manpower markets for the supply of inputs and for the disposal of produced goods and services.

Promoting overall interests of the company and its stakeholders are of paramount importance. In recent times, those who advocate reform of laws governing corporate practices stress the importance of reformulation of the concepts behind these laws.

These are some of the duties and responsibilities expected of a proactive, sincere and committed board of directors who by their actions and decisions will be able to promote the interests of not only the shareholders, but all stakeholders of the company.

The three caselets discussed below discuss how corporate boards and courts of law are holding CEOs accountable for their sins of commission and omission.

Hot Seat Gets Hotter for American CEOs

Accountability of Directors Becoming a Critical Issue

Case 1: A former top executive at Boeing was sentenced to four months in prison in March 2005 for illegally negotiating a $250,000 a year job for an air force procurement officer who was over-seeing a potential multibillion-dollar contract for the company.

Former Boeing chief financial officer, Michael Sears pleaded guilty in November 2004 on a single count of aiding and abetting illegal employment negotiations. Specifically, Sears negotiated to hire Darleen Druyun at the same time Druyun held sway over a contract sought by Boeing that was worth billions of dollars. Federal sentencing guidelines called for a prison term of up to 6 months. Sears’ lawyers sought probation.

US District Judge Gerald Bruce Lee said jail term was appropriate, though he acknowledged that Sears’ conduct wasn’t as severe as that of Druyun, who initiated the job negotiations. “Yours is not equal to hers”, Lee said. Druyun is serving a 9-month sentence at a minimum-security prison camp for female offenders in Marianna, Florida.10

Case 2: American corporate boards fired 103 CEOs in February 2005. Corporate boards are shedding their sleepy images and becoming more ruthless when something’s not quite right at the top. The result: Top US executives are being knocked off their pedestals faster than ever. Boards are asking high-level company officers to hit the road for anything, ranging from financial scandals, lacklustre results, improper insider trades or even an affair with another executive.

According to Challenger, Gray & Christmas, an outplacement and employment research firm, US companies announced 103 CEO changes in February 2005, as compared to 92 in January 2005.

It was the fourth consecutive increase in monthly turnover and the first time in 4-years that more than 100 CEO changes were announced. “A few years ago, most Boards only rubber-stamped the decision of the executive team, but today, they are flexing their muscles and digging into every area of the company,” said John Challenger, the firm’s chief executive.

“They are scrutinising results and second-guessing even decision the CEO makes,” he added. During the previous month, Hewlett-Packard’s board dismissed its Chairman and CEO Carly Fiorina as HP’s merger with Compaq Computer had failed to deliver results. Office Max also ousted its CEO in February after less than 4 months on the job after a billing scandal at office products retailer.

This continued further and there was no sign of the trend getting slow. In March 2005, Boeing’s Harry Stonecipher was ousted for his romance with a female executive, while Fleetwood Enterprises fired its CEO following lacklustre results and a bleak outlook.

One reason for the no-nonsense attitude is the increasing independence of Boards from management. New rules mandated by the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), the Nasdaq Stock Market and the Sarbanes-Oxley law require greater Director independence and expertise. Directors are becoming more fearful of facing legal action if they let fraudulent behaviour go unchecked.

Case 3: Ten former directors of WorldCom were set to pay $18 million out of their own pockets to settle an investor class-action lawsuit. But the deal fell apart in early February 2005, when a federal judge ruled that a key part of the settlement was illegal. WorldCom, a star of the late 1990s telecommunications boom, collapsed in ‘2002 in the largest bankruptcy in US history, facing $41 billion in debt and $11 billion accounting scandal.

“Boards are going to be much more apt to move quickly these days if they are not happy about something”, said Mr Joe Griesedieck, head of CEO recruiting at Korn/Ferry International. Korn/Ferry is planning a boot camp for new CEOs in May 2005. One issue in focus will be the importance of building a constructive relationship with Boards. Another reason boards are adopting a tough stance is the flak they are getting about the compensation they pay to top executives.11

Independent Directors

Who is an Independent Director?

There have been a lot of discussions and debates going on in corporate circles and among academicians in recent times on the need for, role of, and importance of independent directors. An independent director is defined as a “non-executive director who is free from any business or other relationship which could materially interfere with the exercise of his independent judgement”.12

The Companies Act provides a negative definition of an independent director, inasmuch as it renders ineligible eleven categories of persons to be appointed as independent directors in a company, for instance, if a person has held any post in a company at any point of time is disqualified to be independent director of the company. Likewise, any vendor, supplier or customer of goods and services of the company would stand disqualified, notwithstanding the fact that the amounts of transaction are insignificant.13

Desirability of Having Independent Directors

Recent literature on corporate governance is replete with recommendations of various committees on the desirability of having non-executive, independent directors on the boards of companies to promote better corporate governance practices. The Cadbury Report identifies two areas where non-executive directors can make an important contribution to the governance process as a consequence of their independence from executive responsibility. First, reviewing the performance of executive management and second, taking the lead where potential conflicts of interest arise, as for instance, fixing the CEO’s salary and perquisites or dealing with board room succession. Apart from these, independent directors, being non-executives with no vested interest, can bring in objectivity to the board’s decision-making process. Opinions vary on how many independent non-executive directors are required to achieve good corporate governance practice. The UK Combined Code recommended that non-executive directors should make up atleast one-third of the board and that a majority of them should be independent. The IFSA Guidelines and the Toronto Report recommend a higher standard that a majority of directors should be independent, non-executives. IFSA argues that a majority of directors should be genuinely independent in order to ensure that the board has the power to implement decisions, if and when the need arises, contrary to the wishes of management or a major shareholder. IFSA contends that this creates “a more desirable board culture” and imposes a responsibility on the independent majority to be “especially competent and diligent” in carrying out their role.

The Cadbury Report identifies two areas where non-executive directors can make an important contribution to the governance process as a consequence of their independence from executive responsibility. First, reviewing the performance of executive management and second, taking the lead where potential conflicts of interest arise.

The Indian capital market regulator, the Securities and Exchange Commission of India (SEBI) has recently amended Clause 49 of the listing agreement to ensure that independent directors account for at least 50 per cent of the board of directors of listed companies, where an executive chairman heads the board. However, if the chairman is a non-executrive director, at least one-third of the board should consist of independent directors. Several US sets of guidelines prescribe even more numbers of these directors. CalPERS Guidelines recommend that a substantial majority of board members should be independent directors.

Views of Promoters on Independent Directors

While various commitees and foras on corporate governance advocate a sizeable number of independent directors on boards of corporations, and regulators prescribe a large number and equally large role for them, these views have not gone uncontested. Promoters of listed companies are of the view that this is a case of showering authority on people without corresponding, commensurate responsibility.

Their argument is that when a promoter takes most of the risks of the business including offering personal guarantees and pledge of their shares for credit lines in some cases, there is hardly a case for independent directors with no stakes in the business to decorate the boards. If independent advice is indeed required, the same is available to the company from professionals on a commercial basis and directorships need not be offered for this. Moreover, the requirement of 50 per cent representation by independent directors is irrespective of the size of public shareholding. In the case of listed companies with low levels of outside holding, this requirement would amount to a positive discrimination against the interests of the promoter who holds an overwhelming majority of the shareholding and the economic interest in the success of the enterprise.

While voting proportionate to shareholding is recognised in shareholder meetings, many promoters wonder why this has to be any different as far as board representation is concerned. This, some promoters aver, is a classic case of offering power without commensurate responsibility, an impostion of the quota system in a different garb and one more instance of tokenism at work. There is a serious disconnect between the power of decision-making and the economic consequences of these decisions on the promoter. Beyond the usual arguments about representing the interest of the minority shareholder and tenets of good corporate governance, there is hardly any intellectual case made out by the proponents for a disproportionately large share in the Board for independent directors.

After presenting all these negative arguments of promoters, UR Bhat in an article in Economic Times commending SEBI’s move to fill the boards with more inependent directors argues that there is enough research literature on the subject of diversity in managing complex work situations that can be justifiably extrapolated to the functioning of boards of directors. According to him, independent directors should be viewed not as a SEBI-foisted nuisance, but sources of diversity in terms of values and information that enhances the quality of decision-making.14

UR Bhat argues further that instead of interpreting the new SEBI measure as another instance of tokenism, it would be useful for company promoters to view this as an opportunity to improve the qualities of decision-making in boards. The most important aspect, however, is to get high levels of task commitment from independent directors which is the function of the leader. Leadership no doubt, is an important tool of value creation that should get rewarded for taking calculated risks, though in practice, does somethimes get rewarded for not taking risks. The SEBI move is therefore supportworthy for reasons more than just protecting the interests of minority shareholders and good corporate governance.

Directors’ Remuneration

In the wake of several corporate failures, excessive and disproportionately large payments to directors have almost become a scandal. It has also become one of the most visible and politically sensitive issues of corporate governance.

As usual, there are divergent views on the subject. Some experts on the subject are of the view that directors are generally underpaid for their work and the onerous responsibilities they shoulder. They argue that “constructive boards are responsible for untold millons going to the bottomline. The value of a single idea of strategic succession planning, of risk avoidance, and the value one mistake prevented is incalculable”.15

On the other hand, critics argue about the hefty fees directors receive for attending meetings, millions of dollars paid as severance payments, huge payouts as bonus and other perquisites. A major criticism is that exceutives and directors are not properly controlled in their virtual self-awards of stock options. Executive compensation linked to share performance through share options has resulted in encouraging a focus on short term growth with destructive long term consequences.

Executive Pay, an Unsettled Issue

Executive compensation is still an unsettled issue. There is a controversy regarding the quantum of directors’ remuneration, which, however, is not a corporate governance issue. The size of compensation is related to several factors relating to the corporate in question and even to external factors. As discussed earlier, the key corporate governance issues in the matter of directors’ remuneration are: (i) transparency, (ii) pay for performance, (iii) process for determination, (iv) severance payments and (v) pensions for, non-executive directors.

Emphasis on Transparency and Disclosure

Almost all committees in their codes and guidelines—the Cadbury Committee’s Code, the IFSA Guidelines and the Bosh Report, for example—have emphasised the need for openness, transparency and disclosure in these issues. Shareholders have a right to know the quantum, the basis and the manner of payments to directors. The Securities and Exchange Board of India in the recent changes that are effected in Clause 49 have a section that says that compensation paid to non-executive, independent directors should be fixed by the board and will require previous approval of shareholders. Shareholders’ resolution shall specify the limits for the maximum number of stock options that can be granted to non- executive directors, including independent directors, in any financial year and in aggregate, according to the new listing agreement.The remuneration paid to directors should be disclosed in the section on corporate governance in the annual report of the company. This includes details on stock options, pensions and criteria for payment to non-executive directors.

Pay as a Reward for Performance

As there is a considerable stigma relating to excessive executive remuneration, schemes for such payments should be carefully and cautiously structured to ensure that compensations to directors and senior executives do reflect their performance and are in relation to their responsibilites and risks involved in carrying out their functions.

Compensations to directors and senior executives reflect their performance and are in relation to their responsibilities and risks involved in carrying out their functions. One of the reasons in favour of this “pay-for-performance” concept of executive remuneration is that If executive compensation is directly related to an increase in share price, the benefits executives receive would be proportional to those of all shareholders. This would encourage executives to make decisions which will maximise shareholder wealth.

There is a growing acceptance internationally that equity-based remuneration including stock options is an effective way to match remuneration with performance. “Many sets of governance guidelines support the use of shares and options in remuneration packages. An appropriately designed share option scheme will help counter the economic problem of ‘agency costs’, in which the interests of senior executives may diverge from the best interests of shareholders.”16 The argument in favour of such an arrangement runs like this: “When senior executives own shares, they are encouraged to act in the best interests of shareholders because the financial interests and risks of the executives are equated with the interests and risks of the shareholders.”

There are other reasons as well that are adduced in favour of this pay-for-performance concept of executive remuneration. These reasons are given below:

- If executive compensation is directly related to an increase in share price, the benefits executives receive would be proportional to those of all shareholders. This would encourage executives to make decisions which will maximise shareholder wealth;

- The share option also will counter the problem of directors being too risk-averse. This is because of the fact while directors and senior executives are blamed for the poor performance of the corporation, they do not receive the benefits when it performs well. This will lead to directors not taking necessary risks and consequently resulting in the company not doing well. These problems can be eliminated if the company’s performance is used to determine the directors’ remuneration. With regard to remuneration in terms of shares and options to non-executive directors, there are different conventions. In the US, there is no distinction between executive and non-executive directors, both of whom receive share-based remuneration. But IFSA Guidelines, while recommeding the practice to executive directors, prefer non-executive directors to invest their own money in the company. This is recommended because it is the non-executive directors who should be given the responsibility of working out the remuneration package to executive directors and senior executives of the company and the resultant conflict of interest be best avoided by keeping them out. Some writers have worked out a scheme based on recent proposals for improved pay versus performance policies. These are as follows:17

- Limit the base salaries of top executives.

- Base bonus and stock option plans on stock appreciation.

- Stock appreciation benchmarks should consider (i) close competitors, (ii) a wider peer group and (iii) broader stock market indices.

- Base stock options on a premium marginally higher than the current market price and do not reprice them if the shares of the firm fall below the original exercise prices.

- Work out and make available company loan programme that would enable top executives to buy sizeable amount of the firm’s stock so that subsequent stock price fluctuations substantially impact the wealth position of top executives.

- Pay directors mainly in stock of the corporation with minimum specified holding periods to heighten their sensivity to firm performance.

However, it is to be noted that the pay-for-performance plans should be done in moderation. There is a serious concern among investors that directors and executives tend to overuse this privilege and corner a sizeable portion of benefits that should legitimately go to shareholders.

Performance Hurdles