Chapter 8

Money

We started and ended the last chapter on notes of caution. We outlined there a theory of income determination, which was called Keynesian, and which showed that the national income in a country would be determined by the level of aggregate demand. Caution was urged on the reader because the theory was presented in a very simplified form. We omitted consideration of a variety of determinants of aggregate demand in order to focus attention on the role of income itself. Consumption, for example, was starkly said to be dependent on income and investment expenditure was regarded, most of the time, as a constant.

We shall not be able to consider all the determinants of aggregate economic behaviour in this book. One factor that has, however, been excluded is so important that it deserves a chapter to itself. It is money. The reason why we have so far left money out of the explanation of income determination is that our emphasis has been more with output than with the general level of prices. The Keynesian theory, which was used as the basis for the previous chapter, was presented very largely in real terms, that is to say, we ignored the implications for total spending that might follow from a change in the value of money, as expressed in changes in the general level of prices.

The justification for such an approach would be that money, per se, does not matter. Suppose the general price level doubles overnight and everybody's income doubles at the same time. Do consumers and business men behave in exactly the same way the next day as they did before?

It is a good question, by which we mean, of course, that no one really knows the answer to it! It is possible to argue that economic behaviour might be exactly the same, since real income has not altered. But it is also possible to take an opposite view, because not everyone may fully appreciate that the underlying circumstances are the same at all. There may be some kind of 'money illusion' in the minds of the members of the community which makes them believe, even if wrongly, that they are better or worse off when their money incomes rise or fall. If they believe this to be the case, they may very well behave differently and their changed behaviour can quite easily bring about changes in the real underlying situation.

The question about money and behaviour can be put simply as: does money matter? does it have, as it were, a life of its own? or, is it simply a veil, a way of measuring the value of physical outputs? The question, it has already been said, is not definitively answerable by logical argument. Nor can it be settled once and for all by observations of the facts of the real world, that is, by seeing how people actually behave when prices are changing. Economics is not always capable of giving firm answers on such questions of fact. The evidence is conflicting about the importance of money and there is a great deal of controversy among economists about who is right. Two popular schools can be identified. One are the Keynesians, who attribute a relatively minor role to money, and the other are the Monetarists who, under the leadership of the contemporary American economist Milton Friedman, believe that money matters a great deal.

The Keynesian/Monetarist controversy has probably been the most vigorously debated issue in economics in recent years. It is heavily imbued with political overtones, but the implications for economic policy which would follow from the unlikely event of either side collapsing are substantial. We deal in this chapter with some of the major issues in the controversy. Note, however, that it would be quite wrong to assume that all economists are lined up like armies on one or other side of a battlefield. It would be much nearer the truth to see them sitting in a field at the end of a rainbow stationing themselves at different positions in the spectrum, from infra-red Keynesians to ultra-violet monetarists at the two extremes. But the great majority of economists will be found at fair distances from the polar positions. Indeed, happily, one finds some from each camp shifting positions in the light of argument, debate and evidence. Our modest task in this chapter is to try and understand some of the reasons why they are involved in the controversy at all.

The Nature of Money

Stock of Wealth

Money is an asset that individuals and businesses can hold. The first important characteristic to note is that it represents a stock of wealth that gives its owner purchasing power over goods and services, factors of production and other things. It is conceptually different therefore from income which, as we already know, is a flow of receipts that accrue over time. The distinction between stocks and flows assumes considerable significance in economics. Any asset existing at a moment of time, such as money, or unused goods or materials held by a business or by a household, is a stock of wealth. Such assets must be distinguished from flows of income or expenditure, which take place over a period of time. (We have already noted that changes in stocks between two points of time are effectively flows. They are treated as positive or negative investment. See above, page 106.)

Financial Asset

A second characteristic of money is that it is a financial asset. In this connection, money must be distinguished from physical assets, such as capital equipment and stocks of real goods and services.

There is a range of financial assets, of which money is but one. The distinguishing feature of a financial asset is that it gives its possessor a claim to something of value. The deed denoting ownership of a piece of real estate or a house is a financial asset, quite distinct from the property itself. A life assurance policy is a financial asset. So are shares in joint stock companies, securities issued by the government in return for money borrowed from the public and even the IOU held by the winner of a backgammon game.

These financial assets have value because they are claims to something else. The paper on which they are written is intrinsically virtually worthless, unless they happen to be old collector's items. The value of a particular financial asset is not, however, related only to the underlying real asset it represents. This is obvious when it is realised that some financial assets do not represent claims to any real physical assets at all. Some government securities were issued many years ago to raise finance to pay for the waging of wars. The guns and battleships that were purchased have long since ceased to exist. Yet people still hold some of these securities, such as 'consols', the most famous of all, which were first issued in the eighteenth century. They are still of value, not because of the physical assets that they represent, but because the government still honours its obligation to pay an annual sum, the interest, to any persons or institutions who hold consols and other government securities. The statement at the beginning of this paragraph that financial assets are valuable because they are claims to something else remains true, though in the case of government securities such as consols it is the claim to a fixed annual income that gives them value.

Money is a financial asset which shares one feature with government securities. It does not represent any particular physical asset. In another way, however, money is very different from such securities. It does not give its owner any income. You do not receive any interest from anybody on the £5 note you hold.

Money, government securities and all financial assets, however, have one much more important feature in common. They are negotiable, that is to say, they can be sold and exchanged for other things — goods and services, factors of production, or even for other financial assets. Indeed, in the case of financial assets like government securities, shares in joint stock companies and deposits in building societies, they have value which reflects the advantages that accrue to their owners, such as the right to receive periodic income. There is a market for such financial assets and we shall look at it again later in the chapter.

Money, however, as already stated, possesses no rights to income or to the ownership of physical assets. Its value stems solely from its negotiability, from the fact that it is acceptable in settlement of debts. This is one of the prime characteristics of money, which performs a number of functions.

The Functions of Money

Three chief functions of money are usually distinguished. It acts as a medium of exchange, a store of value and a unit of account.

(1) Medium of Exchange

Most transactions involving the purchase and sale of goods, services and factors of production are made through the medium of money. The existence of money avoids the need for direct barter of goods against goods. If you have a radio you wish to exchange for a camera, you will find it much easier to make an indirect sale for money, which you then use to buy a camera, than to advertise in the hope that you will find someone with exactly the opposite complementary wants to your own. Finding such a 'double coincidence of wants', as it is called, can be a lengthy, if not impossible, task. It is rendered unnecessary by money which acts as a medium of exchange.

This prime function of money is of outstanding importance in the process of production. It means that a business can pay its workers with money, which can be used to buy varieties of goods and services, instead of having to pay them with bricks, steel tubes, or whatever the company happens to produce. It is not surprising, therefore, to learn that economists regard money as a vital 'lubricant' in the economic system, allowing specialisation to a high degree by avoiding the need for individual workers (and businesses) to be paid in quantities of their own physical outputs.

To the man in the street, what he regards as money is probably just the notes and coins which he can use to buy whatever he needs. To the economist, money is both these things, but it is something very much more as well, and consists of anything which acts as a medium of exchange by being immediately acceptable in settlement of debts.

(2) Store of Value

Money performs a second important function in addition to acting as a medium of exchange. It is an asset which can be used to store wealth over time. This function of money derives in the main from the fact that payments for goods or services, including those for factors of production, are not always made immediately the purchase is made. Workers are rarely paid daily, even if they are on daily rates of pay. Many goods are sold on credit to households and businesses. Gas and electricity bills are sent out quarterly, cars may be bought on extended hire purchase payment systems over one or two years, houses are often paid for over periods as long as twenty to thirty years and businesses usually trade with each other by allowing a variable time for the settlement of accounts. The function money performs as a store of value is simply that it allows households and businesses to store the debts that they owe, or are owed, until the payments are made or received. This function derives from the existence of time-lags between the transactions in goods and factors and the payments for them.

(3) Unit of Account

The final function of money, not unrelated to the last, is that it aids economic calculations. Economic decision-making would be difficult and imprecise if there were no money to act as a unit of account. Consider a business firm, for example. It needs to decide regularly what operations to undertake, how much to produce, whether to switch to different products, how many workers to employ, whether to engage in capital investment, even perhaps whether to close down altogether. Proper decisions can be made about such matters only if a firm can estimate the effect of any of its decisions on sales and profits. Calculations for these purposes are made in money terms and it is unthinkable that complex businesses could be run efficiently if there was no monetary unit of account in which they could be made. In a similar way, the existence of money aids households to make sensible decisions on spending and assists governments to compare alternative ways of raising revenues to cover intended expenditures.

Liquidity

Money, we have seen, is a financial asset which performs a number of functions. It is able to do so for a particular reason, which has been implied, but not yet specifically mentioned. This is that money is the most liquid of all financial assets. Liquidity is a technical term of particular relevance to money's function of acting as a medium of exchange. In so far as all financial assets are, as previously pointed out, negotiable, this means that they may be exchanged for other financial assets. To an extent, therefore, any financial asset is capable of being used in settlement of debts. If I decide to buy a new car, for example, I may not have enough money to pay for it, but I may have some other financial assets, such as shares in a joint stock company that I can sell and use the proceeds to settle the bill for the car. However, there are two specific disadvantages to paying in this way rather than for cash. In the first place it takes time, and in the second place there is some uncertainty about how much my shares will actually fetch in the market when I sell them. There is even a risk that they will prove worthless.

There is neither delay nor uncertainty in the case of money. I can use it immediately in the settlement of any debt. I know all the time how much of it I have and that it will be an acceptable means of payment. It is true that the prices of the goods I may want to buy with money are liable to change, but that is a different matter. Ten pounds is ten pounds is ten pounds, whereas ten shares in a joint stock company may be worth £10 today, £11 yesterday and only £9 tomorrow.

This feature, which is the advantage that money has over all other assets, is known as its liquidity. Assets are said to be more or less liquid according to the speed with which they can be used for the settlement of debts and the certainty about their money values. We shall return to this subject shortly when looking at the reasons why people hold money at all. Meanwhile, we may conclude that money is the one riskless asset that is perfectly liquid, in the sense that it is immediately acceptable for the settlement of debts. Indeed one definition of what constitutes money is that it is any perfectly liquid asset. Note, incidentally, that there are many other very liquid assets, such as deposits in building societies, which can be drawn on at short notice by account holders. They are known as 'near money'.

The Demand for Money

Now that we know what money is, we can ask the question why individuals and businesses want to hold it. Put like that it sounds a rather silly question. Of course people want to hold money, it is valuable. However, money, as we saw earlier, is only one of a range of financial assets.

Two characteristics distinguish money from other financial assets: (1) it is perfectly liquid and (2) it does not yield any income to its owner. When someone holds money rather than other financial assets, therefore, he or she is opting for liquidity rather than an income. Now the question looks quite different. Why should anyone choose to sacrifice a stream of income in the form of annual payments from the profits of companies, interest from the government, and so on, in order to have a stock of money?

Three reasons are usually given for holding money. They are related to the functions that money is said to perform and are known as the transactions, precautionary and speculative motives.

(1) Transactions Motive

The first reason why people want to hold some of their assets in the form of money is simply in order to make everyday transactions. The need for a stock of money stems from the fact that receipts of both households and businesses do not usually match their payments in terms of time. A typical wage-earner, for example, is paid only once a week or once a month, but needs to pay out general living expenses continually during each period between pay-days. Some of his payments may be fairly regular, such as the daily fare for his journey to work or his quarterly fuel bill. Others may be irregular, such as a visit to the circus or repairs to a washing machine. Many payments and receipts of businesses are not synchronised, too. Workers have to be paid before goods are sold and materials have to be bought in before production can begin. Both households and businesses therefore, have a need for money to pay for these kinds of transactions.

The transactions demand for money depends on the presence of time-lags between the flows of receipts and payments that occur in the normal life of a household or a business. We can go further and say that the greater the frequency of receipts and the closer they match payments, the smaller the demand for money for transaction purposes. Moreover, the institutional and conventional arrangements for settling accounts in the economy are relevant to the demand for money. The growth of credit cards has reduced the need to hold large quantities of notes and coins for individuals and any easing or tightening of the credit allowed by businesses to each other will affect the cash requirements of businesses.

(2) Precautionary Motive

The second motive for holding money is barely more than an extension of the first. The difference between the transactions and the precautionary demands for money is that the former is a response to known needs and the latter to unknown. No one, individual or business, can be absolutely certain of all its cash requirements in the future, because we happen to live in an uncertain world. So, there is a precautionary demand for money, which people and institutions wish to keep as a safeguard against unforseen events.

The size of the precautionary demand for money, then, is related to uncertainty and, in particular, to the community's expectations about the future. The uncertainty can be about real events, such as the likelihood of being laid off work due to sickness, or it can be about financial matters. Doubts about future prices, for instance, may affect the precautionary demand for money.

(3) Speculative Motive

The idea of price expectations, mentioned in connection with the precautionary demand for money, is of much greater importance for the speculative motive. In order to understand the rationale for holding money for speculative purposes it is necessary to go back to the idea of a sacrifice being made when money is held rather than any other financial asset. The opportunity cost of having money in the bank is the income that would accrue from lending it. However, there are two possible motives for buying assets for profit, only one of which is to receive income as, for example, interest or dividends from companies. The second motive is related to the capital value of the asset. People who buy securities may also be fortunate enough to make a capital gain if the price of the securities rises. If people think that the price of an asset is likely to rise, they will buy it for this reason. However, sometimes prices are not expected to rise, but to fall. Capital gains may still be made. In such circumstances the action of a speculator is to sell securities while the price is high and buy them back when the price has fallen. If he behaves in this way he will make a capital gain, just as if he buys on a rising market. But during the time that the speculator is waiting for prices to fall, he may very well increase his holdings of money, the one asset that by definition cannot change in money value.

The speculative demand for money is, therefore, related to expectations about future prices. In inflationary conditions, for example, if people expect prices to rise, and especially if they expect the rate of inflation to accelerate, they will tend to increase their spending before prices rise and, in consequence, to hold less money, which will lose its value. There is one important kind of asset that should be mentioned in connection with the speculative demand for money: securities that yield a fixed rate of interest (as distinct from a variable return, for example, with the profits of a business). Consols, mentioned earlier, are securities issued by the British government and are such fixed interest securities. The holder of consols is assured of £2.50 per annum for every £100's worth of them in his possession. It is a kind of IOU; a promise to pay, not a capital sum, but an annual interest. This is what gives it value. The £100's worth is italicised because the value mentioned is related to what is known as the nominal value which may or may not be its market value. It is quite likely to have been the value of the securities when they were first issued.

If the market rate of interest happens to be 2½ per cent at the time the government needs to borrow money, then it would have to offer £2.50 interest for every £100 it borrows simply in order to attract funds from other borrowers. However, the market rate of interest, as we shall see later, varies with supply and demand conditions. The piece of paper called '£100's worth' of consols may not even have the nominal value written on it. It may merely state that the holder is entitled to receive £2.50 every year from the government. It would, therefore, be worth £100 while the market rate of interest is 2½ per cent.

Suppose, however, that the market rate of interest rises from 2½ to 5 per cent, because of a generally increased demand by borrowers. If the government wants to borrow another £100 it would need to offer £5 per annum and the new security would be worth £100. What would have happened to the value of consols? They would, of course, have fallen in value. More precisely their value would have been halved. If the right to receive £5 per annum is worth £100, the right to the £2.50 per annum (on consols) would only be worth £50. As a matter of fact, interest rates have risen so much in recent years that consols have dropped in price to less than £20 per nominal '£100's worth', implying a rate of interest over 10 per cent.

The point of this rather lengthy explanation should now be clear. There is an inverse relationship between the price of fixed interest securities and the market rate of interest. If the rate of interest is high they will be worth less than if it is low. It is the inverse relationship between these two variables that makes possible capital gains on fixed interest securities and to that extent, therefore, affects the speculative demand for money. If speculators believe that the rate of interest is going to fall they can switch from money into fixed interest securities. If they think the rate of interest is going to rise, they will hold money rather than bonds, which will fall in price if and when the rate of interest moves upwards.

It is important not to overemphasise switching between money and fixed interest securities and giving the impression that these are the only assets in a speculator's portfolio. It has already been explained that there are many kinds of financial assets, with different degrees of liquidity and rates of return. Speculators in financial assets are liable to rearrange their holdings of all of them in anticipation of any price changes. It is the expectations about future price movement which cause switching between money and other assets that we need to emphasise under the head of the speculative demand for money.

The Supply of Money

We have another stage to pass before we can return to the question of how important money is. We know what is meant by money, what functions it performs and what motives lie behind the demand for it. We need only to know where it comes from. In other words, what is the supply of money?

Let us start with the man in the street. To him, the supply of money comprises the notes and coin in circulation. These are certainly money. They fit our definition because they are immediately acceptable for the settlement of debts. In primitive societies money took somewhat different forms. Valuable goods like gemstones and even cattle performed money's functions. The more portable, durable and divisible they were, the better they served the purpose. Intrinsic value was never necessary so long as the tokens conventionally used were readily acceptable in society as a means of payment. Indeed, some things could even be too valuable to make good money, because they were too risky to carry about.

In complex modern societies forms of token money persist in the shape of notes - and coin, but there is another quantitatively more important part of the money supply that fulfils the functions of money extremely well and is, therefore, included by economists in the total. We refer to deposits held in bank accounts. These are the most commonly used means of making financial transactions by businesses, but are widely used also by households. Current accounts carry no interest and are immediately usable. About half of bank deposits in Britain are, however, interest-bearing. They are true deposits (or deposit account balances) and may not always be withdrawable in full on demand. Anyone who has a bank current account has only to write a cheque (which is merely a standard form of a letter to his bank) instructing his banker to pay a certain sum to someone to whom he owes money for any purpose and the payment will be made without any need for transfers of notes and coin,1

The Banking System

Since bank deposits are a major part of the money supply it is necessary to make an excursion into the nature and behaviour of banks. This is a technical subject and our excursion will be brief. (Readers are advised to refer elsewhere for detailed information about the banking system.)

The basic principle by which banks operate is, fortunately, simple enough. Banks are financial institutions whose objective is to make profits by making loans. They are able to do so very largely because people and institutions find it convenient to keep money on deposit in banks.

The business of banking may be illustrated by assuming a very simple economy in which there is but a single bank. Table 8.1 sets out the balance sheet of such a bank, which has just received a deposit of £10,000 in coin from a merchant. The two sides of the account show its assets of £10,000 of coin in the vaults and its liabilities of £10,000 to the merchant, who may, in principle, come at any time to take his coin back again.

Table 8.1 Assets and liabilities of a bank before deposit creation

| Liabilities | Assets | ||

| Deposits | £10,000 | Coin | £10,000 |

| £10,000 | £10,000 | ||

Issue of banknotes

The first observation to be made about the importance of banks in the supply of money is that the banker probably gave the merchant a receipt for his £10,000. Such a receipt, if signed by a reputable banker of good standing, constituted a claim, or financial asset, which could be negotiable, that is, exchangeable in settlement of debt. It is, in fact, a kind of banknote. If you look at a pound note you will see it is no more than a promise signed by the chief cashier at the Bank of England to pay the bearer on demand the sum of one pound. Early bankers were in fact responsible for the introduction of banknotes. The system persists to the present day, though private commercial banks are no longer allowed to issue banknotes in England. This is now the prerogative of the Bank of England.

‘Creation’ of bank deposits

There is a second and crucially important way in which banks are responsible for the supply of money. It arises from the fact that cheques drawn on bank accounts are acceptable for the payment of the great majority of debts. Since cheques are acceptable, bank deposits are, by definition, money as far as economists are concerned.

Let us look again at the balance sheet in Table 8.1. It shows that the bank has £10,000 in its vaults which appears also as a debit on the liabilities side of the account, representing the debt to a customer. Suppose, however, to make the example more realistic, the £10,000 was not deposited by one person but by 100 people depositing £100 each. Why should the banker keep £10,000 worth of coin in his vaults? The only reason his customers deposited money with him was that they had no immediate need for cash. If the bank examines past records of drawings on cash it will find that only a proportion of depositors want their 'money' back at any one time. It would be quite safe to keep a proportion of the total liabilities in cash, basing the proportion on past experience.

Let us suppose that the bank finds that, on average, it is safe to keep enough coin in the till to meet 10 per cent of total liabilities to depositors. What can the bank do? It has £9,000 more coin than is really needed. It is earning no interest either. Hence it would be an idea to lend it to people who want to borrow for various purposes. If the bank does this, it can make a profit by charging interest on loans.

What the bank does is indeed to make loans. But it does not need to lend out coin. The existence of the cheque system, whereby people can make payments to each other simply by writing cheques, means that it is sufficient for the bank to lend merely by opening accounts in the name of borrowers. Thus loans can be made, in effect, by creating deposits in favour of persons and institutions to which the bank lends money.

If a bank works to a 10 per cent safety rule and has £10,000 worth of notes and coin in the vaults, it will be able to make loans to the value of £90,000. The situation after the loans have been made is depicted

Table 8.2 Assets and liabilities of a bank after deposit creation

in Table 8.2. The bank's total assets and liabilities are now £100,000. It has liabilities to all depositors, who have the right to draw coin of £100,000, and it has assets equal to exactly the same amount — £10,000 of coin, and £90,000 of credits representing loans made.

The simplicity of the arithmetic in the last paragraph must not be allowed to obscure the importance of the result. The bank has actually created money, as a result of carrying on its commercial operations of borrowing and lending. The power of banks to create money is limited by the size of the safety rule to which they adhere.

In our example, the saiety rule takes the iorm ot a ratio ot coin (or cash) to deposits, of 10 per cent. This allows the bank to create deposits equal to ten times the cash base it holds in its till. This credit-creating power is sometimes known as the bank credit multiplier. As can be seen from the example, the multiplier is the reciprocal of the cash ratio

In the modern world there is, of course, more than a single bank. This limits the credit-creating powers of any one of them, but it does not affect the multiplier for the banking system as a whole. A more important modification is that banks do not deal in only two assets, coin and loans. They have a whole range of financial assets to choose from. In practice, they do hold cash and make loans (or advances as they are sometimes called), but they also use part of the funds at their disposal to purchase securities of one sort or another. These other assets vary in two important ways: their liquidity and their profitability in terms of the income that they yield. It is beyond the scope of this book to describe them in detail. Suffice to say that the art of banking has been described as maintaining a nice balance between profitability and liquidity — ensuring that there is enough cash to meet normal demands and enough loans at profitable rates of interest. A bank's ability to achieve this target is greatly helped by the existence of the range of financial assets available. Some highly liquid assets, like loans made literally on a day-to-day basis, provide almost as much security as cash itself. And there are other short-, medium- and long-term assets circulating in the money market. A sensible banker has a spread of assets in his portofolio. The only general statement that can be made about them here is that the higher the yield of an asset, the greater the risk likely to attach to it.

The final limitation on the commercial banks' power to create money through lending to depositors is due to the activities of the government. We shall consider the control that 'the authorities' can exercise over the money supply when dealing with economic policy in the next chapter.

The Price of Money

We have one last question to deal with before returning to consider how important money is. We have to say something about the price of money.

In one sense, of course, the price of money is an utterly trivial question — in money terms a pound is always worth a pound. However, in terms of opportunity cost which is, as we learned earlier, what economists are most concerned with, the price of money is a real one. It is the rate of interest that is forgone when one holds money rather than income-yielding assets. It is the interest that one receives or pays when money is lent or borrowed. We should not, therefore, be at all surprised to be told that both the supply and demand for money are affected by the rate of interest. While this statement is certainly true, it does not follow that the rate of interest is determined by the supply and demand for money and by nothing else, though certain schools of thought have emphasised this approach in the past.

Most prices, as we know, are determined by a variety of factors. Even the price of a simple commodity like an ice cream is determined by many variables, including its cost of production, the utility derived from ice cream, the level and distribution of income, the size and age structure of the population, the weather, and so on. The rate of interest is certainly influenced in part by the supply and demand for money, but it is affected by other variables too, because it is the price not only of holding money, but of borrowing and lending for a wide variety of purposes. Some of these are 'real' factors, for example, the demand to borrow by a business for capital investment in plant and machinery. Others are monetary such as the demand to hold cash rather than other financial assets.

The Rate of Interest

It is difficult, some might even say dangerous, to offer an elementary explanation of the determination of the rate of interest. The forces that are involved are too complex to deal with adequately in a brief introductory book. However, with the warning that the student will have to learn a great deal more about the subject in his later studies in economics, we prefer to embark on an admittedly oversimplified explanation rather than leave the subject completely obscure.

The rate of interest, expressed as a percentage, can be viewed as a reward for lending and as a cost of borrowing what may best be described as loanable funds. We can assemble some of the main constituents of the two sides of the market by considering why there are lenders and borrowers.

Demand

Two major sources of the demand for loanable funds may be mentioned. The first and more important consists of investment demand by businesses. As previously mentioned, capital investment is a time-consuming operation. A stream of yields appears only when time has elapsed after a decision to build a new factory or install a machine has been taken. Funds are needed in the meantime to enable investment projects to be undertaken. Capital is, as we know, a factor of production and it is possible to construct a demand curve for loanable funds, derived from the productivity of investment, in a manner broadly similar to the demand for labour as a factor of production described in Chapter 5.

Imagine ail the investment opportunities availaole to a business. They could be arranged in rank order according to their productivities. Some might yield 2 per cent, others 3, 5,10, 20, 30 per cent, and so on. The importance of the rate of interest as a determinant of the demand for loanable funds for investment is not difficult to see. If the rate of interest happens to be, say, 10 per cent, then this represents the cost of borrowing money to finance it (or the opportunity cost of not lending it for a firm providing its own finance). All investment projects yielding more than 10 per cent return on capital invested will in this case be worthwhile.2 If the rate of interest is below 10 per cent, more investment projects will appear profitable; if the rate is above 10 per cent, fewer of them. In other words, there will be a demand curve by borrowers for investment as a function of the rate of interest and it will slope downwards to the right (as DD in Figure 8.1).

In addition to investment demand by businesses we can discern a demand for loanable funds by households who may wish to spend on consumption in excess of their current income, for example, to buy consumer durables on hire purchase. This demand would also be

Figure 8.1 Determination of the rate of investment.

expected to be inversely related to the rate of interest. The higher the rate the lower the demand, and vice versa. The sum of business and household demands might, therefore, be represented by the curve DD in Figure 8.1.

Supply

The supply curve, SS in Figure 8.1, is drawn as upward sloping. This implies that the amount of loans that individuals are prepared to make rises the higher the rate of interest. In so far as lending involves the sacrifice of present for future consumption, it seems reasonable enough that the relationship should be of this kind. It assumes that, ceteris paribus, people prefer consumption now than in the future and, therefore, need to be paid interest in compensation for not consuming now. Moreover, the greater the compensation (the rate of interest earned) the larger the sacrifice people may be prepared to make and the greater the supply of loanable funds.

One source of loanable funds is, therefore, individuals prepared to consume less than their current income in exchange for interest. A second source consists of businesses offering funds on the market instead of investing them in their own businesses. Some further supply may comprise dishoardings of cash balances that either households or businesses are induced to make. A final source of funds of special significance are any increases in the quantity of money, including new bank loans, which, we have seen, are a form of money creation. Such changes in the money supply assume importance in connection with government macroeconomic policy. They will be dealt with in the next chapter.

Market Equilibrium

The rate of interest that clears the market for loanable funds is, as usual, the equilibrium rate. This is where the supply and demand curves intersect, OR, in Figure 8.1. It should be added that any change in a determinant on either the supply or demand side other than the rate of interest causes the appropriate curve to shift in its entirety. For example, a general increase in business confidence which raised the expected profitability of all investment projects would shift the DD curve upwards to the right. Likewise, an increase in the expectation of life of the population after retirement might cause greater provision to be made for consumption in old age and shift the supply curve also upwards.

There is one special feature of the market forces lying behind the supply curve for loanable funds that must be mentioned. It is that the determinants of both the supply and demand for loanable funds include not only the rate of interest, but also the level of income. This fact implies that it is not possible to conclude that it is necessarily the rate of interest that equates supply and demand. The equilibrating agent may at times be, not interest rates, but the level of income.

It makes a great deal of difference whether income or the rate of interest changes. Let us reconsider one of the components of the supply of loanable funds: household income in excess of consumption. This is, it may be recalled, no more than what we defined as saving in Chapter 7 (S = Y — C). We put forward quite a different sequence of events then. A rise in the propensity to save brought about a fall in income. This was the phenomenon of the 'Paradox of Thrift'. The reader is advised to return to this section (pages 138-9) to remind himself of the argument, which may be summarised by saying that the rise in the propensity to save increases withdrawals from the circular flow of income and exerts downward pressure on national income.

We are, therefore, in a state of uncertainty about the effects of a change in the propensity to save. On the one hand it can be argued that it tends to lower interest rates and increase investment. On the other hand, it can lead to a fall in incomes and consequent decline in the level of total saving. In both cases savings and investment are equated, but in the first situation it is the rate of interest that does the trick, while in the latter it is the level of income. It is important to know which way the economy works, because the implications of the two paths to equilibrium are different in a way that might be highly significant. The level of investment rises if interest rates play the key role; it does not do so in the second case. All that happens then is that the level of income falls.

The answer to the question about the effects of a rise in the propensity to save is that a great deal depends on the responsiveness of the supply and demand for loanable funds to changes in the rate of interest. If responsiveness is high, then the postulated increase in savings propensities will tend to force interest rates down. Moreover, if investment responds to interest rate changes rather than to other factors (such as income changes), the downward multiplier effect of the extra savings of Chapter 7 will not take place (or will be to an extent muted).

In terms of the diagram of Figure 8.1, the argument of the previous paragraph can be expressed as being about whether the supply and demand curves are relatively steep or relatively flat. It is not possible to give a very general statement about their real shape because the evidence is not clear and it is highly likely that the degree of responsiveness of supply and demand for loanable funds varies at different times. We cannot take the matter much further here. It is important, however, to point out that the appropriate macroeconomic policy to deal with output and inflation hinges critically on whether interest rates or income levels are the more important determinants of agreggate expenditure and whether changes in expenditure such as in the propensities to save and invest work their way through the economy primarily via variations in interest rates or via incomes. It seems likely that both income and interest rates are important but at times the former and at other times the latter may be dominant. The critical question is 'when?'. We shall consider these matters again in Chapter 9.

Real and nominal rates of interest

One aspect of interest rates that needs attention is the effect on them of changes in the general level of prices. Although we did not draw attention to it earlier, the absence of a clear label on the vertical axis of Figure 8.1 makes the analysis of the diagram ambiguous. There are two possible signs that could be fixed to the axis, according to whether we are measuring the rate of interest in nominal or in real terms, that is, by allowing for inflation.

If we are talking about the nominal rate of interest, then we must take account of the difference between it and the real rate. The distinction can be made clear by an example. If inflation is proceeding at a rate of 10 per cent then a money rate of interest of 15 per cent implies a real rate of return to a lender of 5 per cent.

The introduction of the rate of inflation to an extent complicates the analysis. However, one can expect that if people anticipate a certain rate of inflation to occur they will allow their behaviour to take their expectations into account. This applies on both the supply and demand sides. Exactly how behaviour will be affected depends on all the circumstances of a particular case. However, it may be said that, as a general rule, expectations of increases in the general price level would tend to push up nominal interest rates; though real rates, adjusted for inflationary expectations, may not be affected.

The structure of interest rates

A final point must be made, that our discussion in this section has been conducted as if there were only a single rate of interest, whereas it is common knowledge that there are many different rates ruling in markets where loans are made. Three principal sources of such differences may be suggested. In the first place, loans vary in the degree of risk that attaches to them. Risk differences may be due in turn to the nature of an investment project, the reliability of the individual borrower, the kind of market that the final product will sell in and similar factors. Different rates of interest in these cases would presumably carry risk premiums reflecting the relative uncertainty in each case. A second cause of interest rate differences might be variations in the periods before loans are due to be repaid. By and large, the expectation here would be for loans of short duration to carry lower interest yields than those of long term, because funds are at risk for longer. A third cause of interest rate differentials might be that the capital market is imperfect, in the sense that there are barriers to the movement of funds from sectors where interest rates are high to those where they are low. This explanation parallels that given for the persistence of wage differentials (see above, pages 93-4). Barriers may be institutional, due to information deficiencies or to the presence of monopolistic tendencies on either the supply or demand side.

There is only one other observation to be made about the existence of a wide range of interest rates for loans of different types, risk and duration. It is that businesses in the financial sector of the economy will tend to adjust their portfolios of assets to take account of any changes which affect the structure of interest rates.3 The implications of this statement are quite considerable, but cannot be pursued further at an introductory level.

The Importance of Money

We are at last in possession of sufficient information about the nature, supply and demand for money to bring this chapter to a close by returning to the question asked at the beginning. Does money matter? Since we are going to give two answers to the question, it would be better to state in advance that there are really two admittedly related questions in one. The first is whether the quantity of money is an important determinant of the price level and the second is whether it also exerts a significant influence on the level of real activity in the economy — on the level of national income and employment. We can make a first approach to answering these questions if we think of the national income or output as comprising a volume of physical goods and services valued at their money prices and asking how the quantity of money affects the valuation.

Reverting to symbols in order to reach one of the most celebrated equations in economics, we can denote the average price level by the letter P. The volume of output is the same as the total number of transactions that occur when the goods and services are brought and sold. We denote these by T. So we can interpret PT as a measure of the value of national output — the number of transactions that occur over a period of time multiplied by the average price level.

There is another way, however, of valuing national expenditure (which we know is the same as the national income or output). Since national output consists of goods and services valued in money terms, it can be expressed as the total amount of money in the system multiplied by a factor representing the number of times that it is, on average, used - termed its velocity of circulation. If we denote the quantity of money by the symbol M and the average number of times it is used by the symbol V, we can measure the value of national output — alternatively as the product of M times V — MV.

Both methods of valuation are definitively true. We can, therefore, put them together in what is sometimes known as the 'equation of exchange'.

MV = PT

The Quantity Theory of Money

The equation of exchange does no more than describe two ways of valuing the national output. It does, however, employ a different approach from the one referred to as Keynesian, which was used in the last chapter. Both are concerned with aggregate demand. The Keynesian analysis stresses the determinants of real output, while the equation of exchange concentrates on the nominal value of national income and the general level of prices.

The role allotted to money in the equation MV = PT provides the basis for what is known as the quantity theory of money. The feature which turns the definitionally true equation into a theory of the determination of the money value of output is the nature of V. Specifically, if the velocity of circulation is predictable, the quantity of money, M, assumes a deterministic role. Early statements of the quantity theory of money stressed the tendency for the velocity of circulation to be constant. If V never changed then an alteration in M would necessarily be reflected in a change in the nominal value of output, PT.4

The first question to ask about the quantity theory is whether or not V might be stable. Under certain conditions, it could be argued, V and M might change in opposite directions to each other. Keynes suggested that, in depressed conditions such as existed in the 1930s, this might indeed be what would happen. An increase in the quantity of money might in such circumstances even induce an opposite downward movement in the velocity of circulation. In other words, people would not spend the extra money. It would pile up in their bank accounts. MV would not change if M went up and V went down to cancel it out. Monetary changes would be unimportant.

Reasoning of this kind led to a disregard for the importance of the quantity theory of money. The evidence showed too that the velocity of circulation was not stable, but appeared to vary over the business cycle and, secularly, with structural changes in the banking and financial system.

However, events of recent history led to the reformulation by Friedman of a 'modern' quantity theory which does not depend on V being stable, so long as it is predictable.

The question of whether the reformulated quantity theory of money is sufficiently supported by evidence is a complex and highly controversial one with which we cannot attempt to deal adequately in this introductory book. However, it may be said that the debate hinges, to an extent, on whether economic behaviour is such as to make V reliably predictable. This in turn rests on whether it is possible to identify and quantify the factors on which V depends.

The determinants of the velocity of circulation may perhaps best be understood by recalling the nature of the demand for money, discussed earlier in the chapter (see above, pages 154—8). Given the money supply, the lower the demand by the community to hold money balances, the faster money circulates and the greater the value of V, and vice versa. All the determinants of the demand for money are, therefore, liable to affect also the velocity of circulation. They include the frequency with which payments are made and the more closely they match receipts, the rate of interest and expectations of future price changes.

These are difficult matters. They are also controversial. The evidence can be interpreted in more than one way and different schools of thought emphasise their preferred determinants of the level of output and prices. Economists adhering to the school described as Monetarist stress the critical role of the quantity of money for the nominal value of national income. Keynesian economists, in contrast, while not denying the relevance of monetary forces entirely, emphasise rather the other determinants of real aggregate demand, discussed in the last chapter. The crucial issue, where the two schools differ, relates to the sensitivity of the spending habits of households and businesses to changes in the money supply and other variables.

We cannot pretend to try and resolve the controversy here. But it is possible to argue that there might be a sense in which both Monetarists and Keynesians could both, paradoxically enough, be right — but at different times, or in different circumstances. Take, for example, the question of whether an increase in the quantity of money raises the value of national income. In periods of depression, it might seem plausible that the creation of additional money might be quite ineffective. At the opposite end of the trade cycle, in contrast, during periods of booming activity, it is equally plausible that such increases could well lead to rising nominal output by causing inflation. The former would be described as the Keynesian case, when newly created extra money was not spent but piled up in bank balances. The latter would be the Monetarist case, where excessive increases in the quantity of money showed up in inflation of the general price level.

A second explanation of how the two views of the way in which the economy functions could both be correct is that they might refer to different time periods. Economic behaviour does not always alter overnight. Changes in incomes or in the quantity of money, for example, take time before they are effective. Short-run and long-run consequences might, therefore, be very different. Few Keynesians would deny that continued increases in the supply of money would eventually affect economic behaviour. At the same time, few Monetarists would claim that a change in the money supply instantly affects spending. A part of the debate is, therefore, about how long the time-lags are, as well as whether they may sometimes be too long for comfort. One of the most frequently quoted statements of Keynes himself is that 'in the long run we are all dead'. He made this remark precisely because he wanted to emphasise short-run effects. But it can provide a clue to the resolution of some controversial issues, when two economists are engaged in disputes with different time-periods in mind.

Output and Inflation

There is a final important question about the effects of a change in the quantity of money that was deliberately avoided in the previous section. It is whether such a change which affects the nominal national income is a real or only a monetary one. In terms of the quantity theory of money, given V, does an increase in M leading to a rise in MV cause a change in the real volume of output (T) or merely in the general price level (P)? All we have said so far is that it may cause PT to increase.

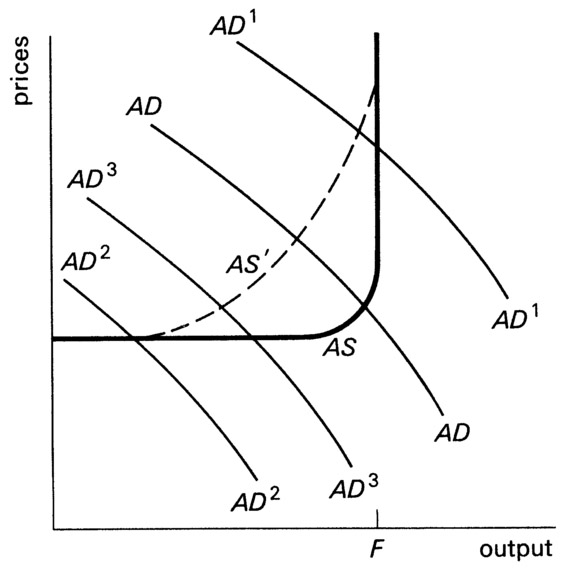

The question can be answered only if we leave the determination of aggregate demand on one side and look at what may be happening on the supply side of the economy. To throw light on the matter Figure 8.2 has been constructed. The diagram depicts four positions of the aggregate demand curve, AD, and two aggregate supply curves, labelled AS and AS'. The latter show the quantity of output that businesses wish to supply at different average general price levels.

Consider, first, the aggregate supply curve AS and the aggregate demand curve AD. Suppose there is an increase in aggregate demand. It can be seen quite clearly that there will ensue a rise in the general price level. The reason can be traced to the fact that the aggregate supply curve is vertical at levels of output above OF, A possible explanation for the curve having this shape is that OF is 'full employment income'. If so, increases in demand cannot, by definition, raise physical output. The full effect must, therefore, be seen in rising prices, or inflation.5 An increase in aggregate demand from AD2 to AD3, on the other hand, produces no upward pressure on the price level, because the aggregate supply curve is horizontal.

Figure 8.2 Output and the general price level.

The argument of the previous paragraph is capable, therefore, of showing that an increase in aggregate demand, brought about by an increase in the quantity of money (or by any other means), may sometimes push the price level up. At other times, the effect is seen, not in changing prices, but in the real volume of output. The decisive factor is the shape of the aggregate supply curve. In the case we have dealt with, the curve AS, changes in aggregate demand are inflationary only at output levels above full employment, OF. Suppose, however, the aggregate supply curve does not look like AS, but like AS'. In other words it slopes generally upwards, rather than having horizontal and vertical sections. If that is the case, then upward pressures on prices would not be confined to income levels greater than full employment, but would be much more general.6 It is obviously important, therefore, to establish the slope of AS. Unfortunately, it has to be admitted that the aggregate supply curve has not been definitively plotted by economists. But in the face of the coexistence of high rates of inflation and high unemployment in the 1970s, it would appear that the curve does slope upwards over quite a substantial range.

Money and the price level

It remains to try and make clear the relationship between the quantity of money and the price level that has been referred to, en passant, in the previous sections. It is not easy to generalise. We have already suggested that the effect of changes in the money supply depends on the extent to which the economic behaviour of households and businesses is affected by it; that there may well be differences in such behaviour in boom and in slump and in the short run and in the long run. There is relatively little difficulty in predicting that excessive monetary expansion in conditions of full employment will put upward pressure on prices, as we saw in the previous section. The issue of greater interest is, rather, how one is to account for high rates of inflation in periods of low output, as experienced in recent years.

There is no single generally agreed explanation of this phenomenon. Wide acceptance exists, however, for the view that in periods of chronic inflation, the community's expectations concerning the future course of the general price level play an important part. We discussed earlier the way in which expectations of accelerating inflation affect the consumption behaviour of households. They must surely affect also investment by businesses and, what has not so far been mentioned, the wage bargaining stances of trade unions.

Suppose the quantity of money increases because banks expand credit. The following is a possible sequence of events. Businesses may immediately increase their investment expenditures in anticipation of selling more output. They may, therefore, take on more labour leading to a fall in the level of unemployment in the short run. What happens next depends on the response of trade unions to the new situation. This, it may be argued, depends in turn upon their expectations of the future level of prices. If the unions think that the rate of inflation is going to accelerate they may make such wage demands as would keep their living standards from falling in real terms. Such action effectively pushes up the price and depresses the demand for labour. The unemployment level may then rise again and output fall back to levels existing before the increase in the money supply.7

Cost and demand inflation

The argument of the previous section should have suggested that inflation is a process, which involves rising prices and rising wages. Indeed, one of the best definitions of inflation is no more nor less than a sustained rise in the general price level. Inflation proceeds over time and it is common to observe a game of leap-frog in motion with prices and wages vaulting upwards over each other. It is not so long since debates were common as to whether the prime cause of inflation was to be found in an increase in aggregate demand or whether there were other factors which raised costs of production and led to higher prices. The controversy was largely a sterile one in as much as increases in costs and in aggregate demand accompanied each other so regularly that the attribution of a causal role to either was difficult to establish. It is no more possible to give a definitive answer to the question most of the time than it is to decide whether the proverbial chicken did or did not pre-date the egg.

There are periods when one can observe an outstanding rise in costs, especially when they originate from overseas, such as the fourfold rise in the price of oil that followed the move by the OPEC countries in 1973. But, most frequently, one observes the shifting of both demand and supply curves. Trying to identify either as the prime cause of inflation is not a very rewarding task.

How Much does Money Matter?

This chapter has been concerned with the question of the importance of money as a determinant of economic behaviour. At the end of it we have to admit that there is at present no general agreement about the answer to the question how much does money matter. The subject is highly controversial and we tried to identify major areas of disagreement between the two major schools of thought, Monetarists and Keynesians, though there are also several intermediate positions adopted by economists.

We might attempt to sum up the debate by pointing out first that there is no dispute about the fact that there is a clear correlation between the quantity of money and the level of business activity in the economy. There is no disagreement to speak of, either, about whether changes in the quantity of money can exert influence. The debates are about how important a factor money is and whether the observed statistical association is basically a causal one — whether, that is, money changes cause income changes or the causal link runs the other way round, from income to money.

Both Keynesian and Monetarist economists study the components of aggregate demand; the former stress the way in which real output is determined; the latter emphasise nominal output. The debate between them ought, in principle, to be resolvable by the facts — by how the economy does behave. The evidence from economic history is not, however, sufficiently clear to settle the controversy. Until agreement can be reached on the responsiveness of aggregate demand and supply to changes in the money supply and in the rate of interest, differences will continue.

It is difficult for any economist writing at the present time to give a totally balanced presentation of the views of different schools on the central issue of the importance of the quantity of money. We suggested earlier that the effects of changes in the money supply may vary in the short run and the long run and in conditions of chronic inflation and depression. There is also a possibility that there may be an asymmetry in the effects of increases and decreases in the quantity of money. Not every economist would agree with these statements. The causal chains through which monetary changes work are complex. There are critical time lags involved in the processes and many of the key relationships are, as already stated, unproven.

One must, however, take some stance on the importance of money if one is to make any recommendations for the conduct of macroeconomic policy, to which subject we now turn.

Notes: Chapter 8

1 If the payee has an account at the same bank as the payer it is obvious that there is no need for more than a pair of entries in the bank ledger, one credit and one debit. But even if there are several banks in the economy, it may be appreciated that, for the banking system as a whole, transfers may cancel out and only book-keeping remains to be done.

2 Investments yielding 10 per cent will also be marginally profitable in the sense that they yield the opportunity cost of capital.

3 Portfolio adjustments might also be expected to follow changes in income, wealth or price expectations. An alternative approach asks whether the proportion of money income that the community wishes to hold as transactions balances, symbolised by k, is constant. V is then the same as ![]() .

.

5 Note, incidentally, a relatively small area of income around OF where the curve is not quite vertical. This could reflect bottlenecks appearing as full employment is approached.

6 To the extent that increases in aggregate demand are not effective in increasing output, the Keynesian version of the multiplier (see above, pages 139-42) needs modification to allow for its stopping short due to inflation.

7 A more extended explanation of the role of price expectations in the generation of inflation, using Phillips curves, is given in the next chapter (see below, pages 182 ff.).