Chapter 10

Economic Policy:

II Microeconomics

We have considered, in the last chapter, problems of macroeconomic policy. It is the turn of microeconomics and we now deal with policy issues relating to the allocation of resources. Some of these have already received attention in earlier parts of this book and we shall be referring back to them. The reader is also advised to refresh his memory of the concluding sections in Chapters 3 and 4 before reading further.

The Goals of Microeconomic Policy

Two microeconomic policy goals may be distinguished, equity and efficiency.

(1) Equity

It is important to emphasise, at the outset, that microeconomic policy is no less controversial a subject than is macroeconomic policy. It is obvious that this is so when the subject of equity is being considered. Equity means fairness and is a matter of personal opinion. One simply cannot decide which of a number of distributions of income, or wealth, is the more equitable, for example, without involving preferences for some individuals over others. The question whether one wishes to favour rich, poor, young, old, sick, healthy or industrious people is an ethical and political one. It is not one on which economists are necessarily better judges than other people. The role of the economist is to make clear the distributional effects of particular economic policies, not to choose between them; though as a citizen every economist will have his own views.

It must be stressed that the goal of equity is not the same as that of equality, which would imply that everyone should be treated equally. Equity, on the other hand, is a much more complex matter. There are many considerations which are relevant to the question of whether a situation is fair. Two are worthy of special mention: the criterion of need and that of reward. They may give rise to major problems when a policy results in a districbution of income which is fair by one standard but less so by the other. The question whether the highest incomes should go to those with the greatest needs or to those who work hardest is an ethical one, though it has important economic implications, for example, for the size of the national income which is available for distribution.

(2) Efficiency

The goal of efficiency might seem, at first glance, much less troublesome. However, this is not the case as readers who recall the argument of Chapter 4 will appreciate. A very concise summary of that argument is that it is not possible to assess the efficiency of the allocation of resources in a market economy independently from equity, because the forces of supply and demand are affected by the distribution of income. People have different tastes and demand for different goods and services varies with income. Consequently, two or more distributions of income can produce different collections of goods and services, through the working of the price mechanism. It was argued in the previous section that we cannot choose objectively between one distribution of income and another from the viewpoint of equity. It follows, therefore, that we equally cannot unequivocally prefer the combination of goods and services produced with one distribution of income to that with another.

Efficiency, like equity, is not a simple concept. In the sense it has been used so far, an efficient set of goods and services means a set that best satisfies consumers. Efficiency is also relevant to production techniques. This can best be understood by ignoring the problem of the first paragraph of this section and assuming it has been decided which goods and services shall be produced. Efficiency can be brought in at this level by declaring that goods should be produced in the most efficient manner, that is, employing the most efficient techniques. Production methods will be efficient if it is not possible to produce more of any goods without producing less of any others. (The economy will be on the production frontier, as in Figure 3-4 in Chapter 3)

Choice of techniques necessarily involves consideration of the prices of factors of production. For example, in so far as relative scarcities lead to the price of capital being low relative to the price of labour, it would be efficient to adopt capital-intensive production techniques. However, factor prices cannot be discussed without recognising that personal incomes depend upon them. Hence, we may see that income distribution impinges on even this aspect of efficiency. A complete discussion of microeconomic policy, therefore, requires consideration of all interactions between equity and efficiency. It will necessitate also accepting that the two criteria may suggest conflicting actions. We may leave this on one side for the moment.

The Price Mechanism and Market Failure

There is no single correct way to approach the subject of the efficiency and equity of the allocation of resources. However, the UK is an economy where major sectors are in private hands, so that the forces of supply and demand result in the production and distribution of goods and services. It has been argued several times previously that a case can be made for approving the allocation of resources brought about by a pricing system. We start by summarising the argument briefly. We then examine the main reasons why a completely free market system may fail to operate ideally, repeating some earlier considerations and adding some new ones. Finally, we describe the various instruments of microeconomic policy available to deal with market failures of different kinds.

The case that a freely working pricing system might bring about a satisfactory distribution of resources was set out in Chapters 3 and 4. It is the so-called case for laissez-faire, that self-interest drives individuals in such a way that state intervention is unnecessary. It is not a case that is accepted in its entirety by anyone, but it has certain merits which deserve consideration. Moreover, the analysis provides a starting point for the identification of particular reasons why the market fails to operate ideally. Such an anatomy of market failure may then form the basis for the analysis of the case for intervention.

The Case for Laissez-Faire

We might summarise the case as follows.

If we assume that consumers always adjust their expenditure on goods so as to maximise their satisfaction, given their tastes and the relative prices of the goods and services available to them, then we may infer that the price that is paid at the margin (that is, by a consumer who finds it just worthwhile buying one more unit of a product) is a measure of the satisfaction he derives from a good. In other words, price measures marginal utility.

We now add the further assumption that producers always maximise their profits, given the prices of the factors of production and consumer demands. Producers find their optimum outputs where the marginal cost of producing a good is equal to the marginal revenue received from selling it. Provided each producer can sell as much as he wants at the market price, marginal revenue must be equal to price. Therefore, we can conclude that the market brings about equality between price and marginal cost. In other words, the cost of producing the 'last' unit of each good is exactly the same as the satisfaction that it brings. If output were smaller, marginal cost would be less than marginal utility, so that an increase in production would be valued by consumers at a figure in excess of the extra cost that would be involved in producing it. Conversely, if outputs were larger than at the point where marginal cost equals marginal utility, a reduction in output would bring a larger fall in costs than in benefits.

Moreover, we must remember that costs are real opportunity costs, measuring the sacrifices of goods not produced. Hence, provided marginal cost equals marginal utility in every market, no reallocation of resources between products can bring about a better pattern of production. Prices, acting as signals, direct resources to the uses which maximise the satisfaction of consumers. In such circumstances, provided the system works reasonably speedily, it might be argued, interference with the freedom of the market mechanism to work towards the best allocation of resources is unnecessary.

The Relevance of Laissez-Faire

In Chapter 3 we examined the way in which the price mechanism functioned through the interaction of supply and demand. Towards the end of that chapter we set out six conditions which should obtain if a market system is to work efficiently. Let us remind ourselves of these conditions. They can provide a basis for the understanding of microeconomic policy. For a pricing system to lead to a satisfactory allocation of resources, it was said that:

- markets must be efficient in the sense that buyers and sellers are well informed and supply and demand must respond reasonably quickly to price changes;

- buyers and sellers must aim at maximisation of satisfaction and profits;

- there must be effective competition of both sides of the market;

- the distribution of income and wealth must be 'optimal',

- the only goods and services must be those that benefit individuals as individuals;

- the social, legal and institutional framework must be regarded as satisfactory.

The Causes of Market Failure

The analysis of the previous section was designed to set out the assumptions necessary for the price mechanism to allocate resources ideally. We next examine the case for laissez-faire from a critical viewpoint. Analysis of market failure may appear destructive. Its importance lies in the identification of causes for criticism and in the provision of a framework for the discussion of microeconomic policy. If a doctor knows the causes of a disease as well as being able to recognise it, he will be more likely to cure it than merely to relieve its adverse symptoms.

There are a number of different ways of grouping together the causes of market failure. The fivefold classification chosen here involves certain overlaps but happens to suit our circumstances.

- The distribution of income and wealth.

- Market imperfections.

- Time-lags.

- Private versus social values.

- Paternalism

(1) The distribution of income and wealth

The first reason for questioning the allocation of resources brought about by a freely working market system is that the distribution of income and wealth, within which the price mechanism works, may be regarded by society as less than satisfactory. We shall not waste space by repeating the full argument. It was stated at length earlier in the book and summarised at the beginning of this chapter. We know that market forces can result in a different selection of goods and services for each alternative distribution of income and wealth.

The price mechanism, of course, affects income distribution through the operation of markets for factors of production. We saw in Chapter 5 how these work. The demand for a factor, such as labour, reflects its productivity. Its supply represents the numbers of persons offering their services at different wage rates. Equilibrium obtains in each market at a price which equates supply and demand so that there are no unsatisfied buyers or sellers of labour services.

The question of whether the distribution of income resulting from the operation of the price mechanism is equitable and efficient is not, as was argued earlier, one to which an answer can be given objectively. It is a matter of opinion and personal value judgements are inevitable. We can, however, indicate the ways in which certain social and institutional arrangements may affect supply and demand in the market. They suggest some of the reasons why personal incomes differ and allow us to take better-informed stands on whether we approve or dissaprove of the results.

Explanations of income differences were dealt with in Chapter 5, so we need only summarise them here. First, an individual's income may accrue from more than one source — for example, a wage from employment, interest or profits derived from the ownership of capital, and so on. One cause of different incomes is, therefore, to be found in the fact that some people have more sources than others. This is particularly important because wealth is, by and large, more unevenly distributed than is earned income. Secondly, money wages are sometimes low or high because there are non-pecuniary advantages and disadvantages of different occupations. Thirdly, individuals vary from each other in a great many ways which influence their productivity and, therefore, their earnings. Some of these characteristics, such as ability and personality, may affect work drive or taste for risky, high-paid employment. It is not within the competance of economists to know how far they are innate or produced by the environment. For policy purposes, however, it may be useful to know how far they are within or outside an individual's control. No one can do much about his age, sex or race, for example. Other characteristics are, however, more capable of influence, if not always by the individual himself, at least by government action. The most important illustration of a quality which affects skill and earnings is the education and training a person has received. A fourth cause of differences in incomes is the existence of various barriers which hinder the movement of individuals from low-to high-paid occupations. Such barriers may be geographical. They may reflect the time needed to acquire new skills for workers in industries contracting as a result of economic progress. They may be merely informational barriers, which prevent everyone knowing where there are job vacancies paying relatively high wages. Fifthly and finally, it must be recognised that labour markets are not all perfectly competitive. Wage negotiations are conducted by trade unions and employers' organisations which possess varying degrees of monopoly power. The result is that wages for comparable skills may differ by occupation and by industry.

We conclude that there are many possible explanations for uneven distributions of income in a country at any time. They are complex and usually difficult to unravel; particularly so because the available statistics are not entirely reliable. Much of the data comes, for example, from tax returns; not the most credible source! There are also problems in interpreting the statistics, allowing for under-recorded income, fringe benefits, part-time employment, and so on. It can be said only that unless we can identify (or be prepared to guess at) the causes of differences in incomes between persons, we shall find it difficult to decide whether we regard the distribution itself as being unsatisfactory or not, and what to do about it. For instance, if we find a man to be low paid because he chooses a job he likes we shall probably be less concerned than if his low income is due to being disabled.

(2) Market Imperfections

It was explained earlier that our fivefold analysis of the causes of market failure contained some overlaps. We have already seen in the last section that imperfect competition may be a cause of income differences. However, there is a special reason for considering market imperfections in their own right.

The basis of the argument was that explained in Chapter 4 and the reader is urged to refer back to pages 72 ff. for a full statement. It should be recalled that one of the necessary conditions for laissez-faire to bring about an efficient allocation of resources is that output should be 'optimal', in the sense that marginal cost equals marginal utility at the margin of production. Prices, acting as signals, perform the function of achieving this automatically under conditions of perfect competition. However, when markets are less than perfect, producers are price-makers rather than price-takers. Marginal revenue is less than price. A profit-maximising monopolist produces output where marginal cost is equal to marginal revenue. This is, in consequence, where marginal cost is less than marginal utility. The situation was illustrated diagrammatically in Figure 4.11, which showed that a profit-maximising monopolist produces less than 'optimal', perfectly competitive, output. In addition to this kind of resource 'misallocation' that may accompany less than perfectly competitive markets, it was shown in Chapter 4 that firms in monopolistic conditions may also be less subject to competitive forces inducing them to keep their costs to a minimum. The present of such 'X-inefficiency', as it is called, when managers are shielded from competition, is a second reason for treating imperfect competition as a separate cause of market failure.

When we were discussing the relevance of income distribution to the efficiency of a market system we emphasised the importance of trying to identify the causes of whatever was regarded as unsatisfactory. The same is true here. It is essential to know the reasons why a firm possesses monopoly power to be able to decide what, if anything, could or should be done about it.

A useful approach to this question in any particular case is to ask why competition is not perfect, that is, why there is not a large number of firms in the industry producing an identical product. The answer may be the existence of barriers to the entry of other firms so that one, or a few of them, can hold and maintain a dominant position in the market.

It is necessary to understand the nature of the different kinds of barriers to entry before one can properly discuss microeconomic policy in this area. The sources of power that a firm may have in a market are many and varied. They may stem from the ownership or control of the supply of a raw material, from rights, such as patents, acquired by law, from the fact that the products of a firm are differentiated in the minds of consumers, or from geographical isolation, which can turn a small shop into a local monopoly. There is, however, another source of monopoly power which has important implications for policy. It is the power which stems from the existence of economies of large-scale production. Such economies of scale arise usually from technological factors making highly capital-intensive methods the cheapest way of producing a given output. They constitute barriers to entry of new firms as effectively as any other circumstance.

The importance of identifying the source of monopoly power in individual cases may now be understood. For example, if a monopoly rests on the possession of patent rights, a firm could be forced to allow others to engage in production under licence. If monopoly power in another case is due to consumers believing, unjustifiably, that the products of the firm are different from those of other firms, because of advertising or other cause, a remedy might lie in improving information services available to the community.

It would be possible to multiply examples of alternative solutions to monopoly problems by reference to different causes of monopoly power. But there is one particular kind of entry barrier that we have already noted has special implications for policy. When a monopoly is based on economies of large-scale production, we are faced with a problem which calls for a quite different approach. The reason is that such a firm, if it operates efficiently, must be the lowest-cost producer. Any attempt to break its power by easing entry for other firms would fail in one vital respect. Two or more firms sharing the same market would necessarily face higher costs of production than a single firm, often known, therefore, as a 'natural monopoly'.

The situation is illustrated in Figure 10.1. This diagram is similar in every respect, save one, to the standard diagram of monopoly in Figure 4.11, explained earlier. The distinctive feature of Figure 10.1 is that the cost curves of the monopolist continue to decline until they cut the demand curve. The profit-maximising monopolist would produce output OA compared to an 'optimal' output of OB, where marginal utility is equal to marginal cost. The cheapest way of producing OB output is, however, for a single firm to do so.1

We see, therefore, that special policy problems are likely to arise when monopoly power rests on technical factors giving rise to economies of large-scale production. Breaking up such a monopoly is liable to raise costs of production. Preferred solutions might then lie in finding ways of inducing a monopolist to expand output. Even this kind of policy would be deficient, however, if there is suspicion of 'X-inefficiency' being present, raising the firm's cost curves (without altering their downward tendency). Public policy to deal with natural

Figure 10.1 A 'natural' monopoly. Costs decline until market demand is satisfied.

monopolies is therefore particularly awkward.2 State regulation, or even nationalisation, is often proposed for them, for example, in the power and transport industries. Government ownership or control does not of itself dispose of their basic economic problems. We return to this matter below. (See pages 221—3.)

(3) Time-lags

The third cause of market failure is more straightforward than the first two. The essence of the case for laissez-faire, with which we should by now be familiar, is that market forces by themselves lead to a satisfactory allocation of resources. However, it is in the nature of things that supply and demand do not respond instantaneously. They take time to work. The question is whether they work fast enough or need to be speeded up. We might note, first, that there is another overlap here with the last cause of market failure. The longer the time allowed for market forces to work, the easier it is for firms to enter industries where a monopoly is active. Patents run out, information spreads and monopoly power tends to wane.3

At the microeconomic level, the relevance of time-lags must be viewed sector by sector. One example may be given where the price mechanism is often judged to take too long to work by itself and government intervention is common. It is agriculture.

Many agricultural products characteristically operate in conditions both of inelastic demand and of inelastic supply. Demand is not very responsive to price changes for certain basic foodstuffs, such as bread. The same is true of a number of agricultural raw materials because they form very small proportions of the total cost of a finished product. (Think, for instance, of the price elasticity of demand for corks by wine importers.) On the supply side, price inelasticity stems often from high storage costs and the existence of time-lags between planting and harvesting. They can be as long as seven years (for a rubber tree), and can lead to low elasticity of supply in response to price changes.

When a market operates in conditions of great inelasticity of supply and demand, there is a tendency for prices to fluctuate substantially with quite small changes in demand or supply. The analysis was illustrated with the aid of a diagram, Figure 4.8, in Chapter 4. Readers are referred back to remind themselves of the argument. The conclusion reached there was that not only prices, but also farm incomes, tend to fluctuate more than may be justified. Farmers are inclined to be relatively well off when harvests are small and badly off when they are large.

We should be used by now to the idea that the best way of tackling each of the various symptoms of market failure is one that is related to its proximate cause. Excessive fluctuations due to the vagaries of the weather are examples of cases where it is clearly impossible to change climatic conditions. Government intervention in agriculture, therefore, tends to be of price support kinds aimed at stabilising farm incomes. Time-lags in other cases may be more effectively dealt with directly. For instance, labour mobility may be speeded up by state-aided training schemes in new skills and firms may be assisted financially to relocate themselves in areas where unemployment is relatively high.

(4) Private versus Social Values

The next cause of market failure is linked to the fifth condition listed above on page 207 for the price mechanism to work efficiently, namely, that the only goods and services should be those which benefit individuals as individuals. If this is so we might reasonably expect the total satisfaction of the community to be the simple sum of the satisfactions of all the individuals in it. However, this is not always the case.

Let us once again remind ourselves that price acts in a market as a signal of both the marginal benefit to consumers and the marginal cost of production of a good. Under the 'right' circumstances, as we have seen, the marginal cost to society of resources employed in producing a good is equated to price, which itself is a measure of the marginal utility, or benefit, that it gives.

Implicit in the argument is the idea that the price paid by a consumer for a good is a measure of the satisfaction which he gets from it. Provided the person buying a product is the only one benefiting from the purchase and that the producer of a good is the only one who has to bear the costs of producing it, the price mechanism cannot be faulted on this count. For certain goods and services, the individuals buying and selling them are the only ones involved in costs and benefits. For other goods, however, price does not indicate benefit or cost to society, although it might perfectly well measure utility and cost to the private individual.

Let us take an example of two goods. Compare a service such as smallpox vaccination with one like a visit to a greyhound race meeting. When someone pays to attend a race meeting, the only consumer benefit we can reasonably expect to accrue is that to the person who goes there. This we term private benefit. In fact this private benefit is all that is likely to accrue here. No one other than the individual concerned derives satisfaction from his visit to the races as a rule.

In contrast, consider the case of a smallpox vaccination, the benefit deriving from which extends beyond that rendered to the person vaccinated in so far as it reduces the risk to other people of contracting the disease. In this case we say that there are what are called external, spillover, or neighbourhood effects, and that social benefits are greater than private benefits. Consequently, if the output of race meetings is expanded to the point where the marginal utility to the individual paying for the service is equal to the marginal cost of providing it, the price mechanism will result in exactly the 'right' numbers of race meetings. But if the same policy is applied to smallpox vaccinations, output will be expended only up to the point where marginal utility to the person vaccinated is equal to marginal costs. Output, however, will be too small, because the amount spent by individuals on vaccination does not fully measure the benefit deriving to society as a whole. In other words, marginal utility to society (called marginal social benefit) exceeds marginal cost of production.

External effects are probably quite widespread throughout the economy, although they may be difficult to quantify. Moreover, while social benefits can be greater than private benefits (as in the case of smallpox vaccinations) they can also be less than private benefits, when expenditure by a private individual reduces, thereby, the satisfaction of someone else. If, for instance, I build a tall house next to yours and block your view, or smoke a cigarette in a confined space, you may suffer.

The examples given so far relate to consumption. Equally well, externalities can be on the side of costs. If a business starts a training school for its employees, some trained personnel may leave and work for other businesses, which may profit from lower costs without fully paying for them. If a fish cannery starts up next to a perfumery, the latter may be forced into making special expenditures to prevent fishy smells affecting its perfume.

Public goods. There is one special case involving external effects which is of great importance. This occurs with what are known as public goods, which have marginal social costs approaching zero.

A classic example of a public good is a lighthouse. Once built, the marginal cost of maintenance is very low, and it costs no more to shine for a thousand ships than for a single one. To put the matter in another way, a product may be called a public good if, when one person has more of it, there is no reduction in the quantity available for everyone else. Consider a television programme, which costs as much to put on the air for one viewer as for a million. Compare it with a private good, such as the egg I had for breakfast. When I ate it, there was nothing edible left for anyone else.

Public goods are sometimes termed collective consumption goods to include education, health, defence, and so on. We must be careful to distinguish the technical meaning of the term public good from its occasional loose use to describe any goods and services that governments happen to provide.

A freely working price mechanism will not secure the production of the 'right' amount of public goods, because if marginal cost is zero, then only a zero price is appropriate, and no business will produce goods to give away free. The state may, therefore, decide to intervene, as in the case of goods with some external effects, to encourage or discourage production by means of taxes or subsidies where there are net social benefits or detriments. On the other hand, the government may prefer to deal with the situation by making rules, such as the law that motorists must have insurance to cover third parties who may be hurt through no fault of their own.

There are three major problems to be solved where there are goods for which private and social costs differ.

- How to quantify the benefits and costs, including all external effects, in order to decide how many should be produced.

- How to decide whether they should be produced by the state or by private enterprise.

- How to decide on the best price at which the goods should be sold.

To solve the first problem, elaborate statistical exercises to measure social costs and benefits (known as social cost-benefit analyses) are often undertaken. The second is mainly a political matter, and resembles the problem of whether natural monopolies, dealt with earlier, should be nationalised. The third problem also contains political difficulties. If marginal cost of a public good to the individual is zero, then the only efficient price is also zero — that is, the products should, perhaps, even be free.

(5) Paternalism

Hie final set of reasons for doubt about whether a free market would result in an ideal allocation of resources stems from the last of the conditions listed on page 207 for a laissez-faire market system to work reasonably well: namely, that the social, legal and institutional framework must be satisfactory. There is one aspect of this condition of particular concern. It is related to the rights of the individual to make decisions for himself. We are not concerned here with the spillover effects of a person's behaviour on others (which was dealt with under the head of private versus social values) but with the freedom of the individual to look after his or her own best interests.

Sometimes societies take the view that the state should adopt a paternalistic role, like a father who prevents his child from injuring itself and forces it to do things which it would not choose to do itself, but which are beneficial. Interfering with the freedom of adults is, of course, a very different proposition from that of directing children. Hence, feelings run high on the question of how far the state should limit personal freedom. Nevertheless, there are activities where it is widely accepted in many societies that individuals may not be able to make the best decisions for themselves. For example, it is argued that a person may not realise that certain drugs are habit-forming or injurious to health or that driving on bald tyres increases the risk of accidents. Even if he is aware of the dangers, a man may choose to ignore them and a paternalistic state may deem it right to stop him injuring himself. No wonder strong opinions are heard on this subject!

A less controversial example of paternalism arises from the observation that human beings appear to be somewhat myopic. They tend to pay less attention to the future than perhaps they should, or at least as much as they might wish in later life they had done. Hence, if the state forces people to save, for example, during their working life to provide for a degree of comfort in old age, they may be happier in the long run. Similarly, since the pleasure one can get from reading 'good' books or hearing 'good' music cannot necessarily be fully anticipated before the event, the government may decide to subsidise public libraries and the arts.

Strict paternalism probably accounts, too, for at least part of government expenditure on education, since the beneficiaries (the pupils) are not normally the purchasers (the parents) of education services. We may also include under the paternalistic heading those actions of a government which are sometimes described as 'non-economic'. Society, through its government, prohibits certain types of trade which might other wise be carried on between willing parties. For example, you cannot buy the services of an expert to take your exams for you. Nor can you pay or be paid to commit murder, or deal in slaves. These and other activities are taken out of the marketplace by governments seeking to provide what is currently believed to be a 'civilised' environment. Even defence expenditure is sometimes included in this category, although it might equally well be considered a public good, since defence cannot be provided for one citizen without also being available for another.

The Instruments of Microeconomic Policy

The discussion of microeconomic policy in this chapter has been fairly theoretical. We have sought to set out the case for and against a system in which the allocation of resources is determined by market forces, in order to provide a framework within which particular problems of economic policy may be discussed. There are a great many such problems and we shall discuss a few of them to illustrate some general principles. This section describes the chief instruments of microeconomic policy that are available to governments.

It is useful to distinguish two very general approaches to policy when the market system is regarded as having failed. One is to try and make the market work better and the other is to replace it. The former approach accepts the signalling value of prices, while admitting that the prices ruling in free markets do not always succeed in bringing about an ideal allocation of resources. The latter approach implies that the price mechanism has failed so seriously that it should not be tampered with, but replaced by an alternative allocative mechanism.

Improving Market Efficiency

Let us deal first with policies aimed at trying to make the market system work better. Two kinds of policy instruments may be distinguished. The government can attempt to influence market prices or it can introduce rules and regulations aimed at improving the framework within which the market operates.

Pricing policies

In certain circumstances, the most effective means of improving market allocations may be through the price mechanism itself. The best way of explaining why is by illustration. Take the problem of pollution, for example. As argued in the section on social versus private costs, the presence of externalities carries the implication that market prices fail to take account of social considerations which do not directly enter into the private cost calculations of suppliers. Specifically, private costs ignore any detriment to the environment from pollution, which may incidentally affect consumers and/or producers.

Taxes and subsidies. One solution to this problem might be for the government to estimate the external costs imposed on others by the producers who are responsible for pollution and to levy taxes on them equal to the excluded costs. The effect would be to change the price received by such producers, so that it reflects the full social costs of their actions and not merely private costs. Their maximum profit output should, in consequence, fall, thereby reducing the level of pollution.

Taxes may, thus, be used to influence resource allocation while retaining the basic market system. It should be added that this form of intervention will work satsifactorily if production decisions are sensitive to price changes and if the state can make reasonably reliable estimates of social costs. The sensivity of production decisions to changes in price is an important issue. If the supply curve is inelastic, such a policy is hardly likely to succeed. (Refer back to Chapter 4 if you need reminding of the meaning of the elasticity of supply and of how to use supply and demand analysis to predict the effects of the imposition of a tax on a commodity.) However, there is more to it than that. The nature of the tax itself is relevant. For maximum effectiveness the tax should be linked to output, because the object of the exercise is to induce producers to recalculate the profitability of different levels of output when full social costs are included in the price they receive. A tax which took the form of a licence fee and was not, therefore, directly related to output would be barely effective. It is true that a business might cease production entirely if the license fee absorbed its whole profit. However, if it was smaller, output could be unaffected (though profits lower), since there is no change in receipts, at the margin, from additional sales. The way to affect production is to use the tax to reduce the profitability of each unit of output, thereby changing financial incentives for producers.4

Pollution is only an illustration of a case where taxes may be used to try and correct deficiencies of the market. There are many others. Taxes may, in principle, be imposed anywhere in order to make price reflect full social costs. They may, for example, be levied on goods, such as tobacco, which are believed to be harmful to health, reflecting a paternalistic cause of market failure. Taxes may also be used in the factor, as well as in the goods, market to improve the distribution of income. Progressive rates of income tax, which absorb higher proportions of the income of the rich than of the poor, usually have this aim. Taxes on wealth may have similar obiectives.

Finally, we should make reference to negative taxes or, as they are usually called, subsidies, which can perform similar functions of encouraging production where social benefits exceed private benefits and a free market supplies insufficient quantities. Subsidies to the arts, universities, housing and many other goods and services are often justified on such counts. Subsidies may also encourage factor mobility, when certain regions in a country are relatively heavily depressed. They can be used, too, to improve the distribution of income, where individuals at the bottom of the scale are not liable to tax and cannot, therefore, benefit from low tax rates.

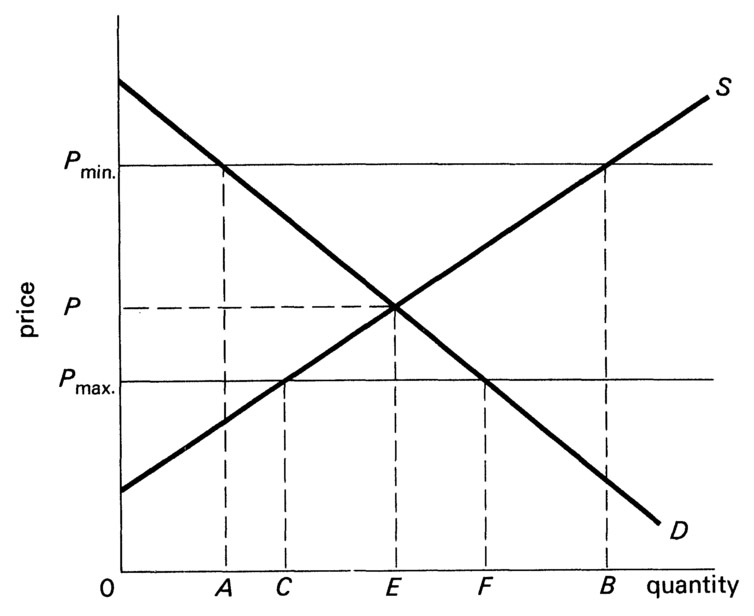

Price controls. It would be wrong to leave the subject of state intervention using the price mechanism without adding that taxes and subsidies are not the only means of trying to affect output and/or consumption decisions. Price controls may achieve similar ends. The authorities may stipulate either maximum or minimum prices. The former have the effect of changing the demand curve facing a producer (making it perfectly elastic at the maximum price). They might, for example, be used to try to stimulate output from a monopolist. Legally fixed minimum prices affect the supply curve (making it perfectly elastic at the minimum price). They could be adopted, for example, to establish a floor to wages in conditions where free market forces would otherwise cause hardship.

Figure 10.2 illustrates the use of price controls. In the absence of intervention, the market settles at an equilibrium price of OP and quantity of OE. If a maximum price is set at OP max., the market will only supply OC. This may be the desired price, but it is important to note that there will also be an unsatisfied demand (CF) at the legal maximum price. In the absence of intervention, the presence of excess demand over supply would tend to force price upwards. Here it is prohibited. If nothing further is done, one might not be surprised, therefore, to find queues or black markets developing (as, for example, with cup final tickets). Hence price controls are often accompanied by procedures for the orderly allocation of scarce supplies (for example, residence qualifications for council houses or ration coupons for food in wartime).

Minimum prices create parallel but different problems. In Figure 10.2, if the legal minimum price is set at OP min., there will ensue an excess of supply over demand, of AB. In a free market, economic forces would tend to lower price. This is excluded here, so one must expect some output to be unsold. Suppose, for example, the market was for unskilled

Figure 10.2 Price controls effecting market equilibrium.

labour and the minimum price was introduced by the government to put a floor to wages. Unemployment, however, would ceteris paribus, tend to occur. (AE fewer workers would find jobs than if wages were allowed to fall to the equilibrium level.) It would, therefore, be unwise to introduce such a measure without recognising its full implications.5

Rules and regulations

We turn next to consider how the state can exert influences on markets by means of rules and regulations. These can take the form of absolute prohibitions and compulsions or more general measures affecting the legal and institutional framework within which the price mechanism works.

Rules of absolute prohibition or compulsion may be resorted to when supply and/or demand is insensitive to price, when alternative policies are impracticable or very costly, or when the allocation of resources brought about by market forces is considered so unsatisfactory that nothing less will do.

It may be helpful to give a few examples of this type of intervention. Certain kinds of pollution may be absolutely prohibited, where the effects would be extremely serious or where the cost of measuring pollution and monitoring a system of taxes would be very expensive. Bus lanes may be barred from private motorists; factory building may be forbidden in highly congested areas; the import of animals carrying health risks may be banned; and so on. Absolute prohibitions, of course, deprive individuals of freedom of choice. In some cases, compromise solutions of partial bans may be appropriate — for example, the division of trains into compartments where smoking is, or is not, allowed.

The examples given in the previous paragraph are of rules declaring activities illegal. There is no clear dividing line between them and measures of compulsion. For example, the law requiring employers to adopt policies of equal pay for men and women can be seen also as a ban on pay discrimination by sex. However, there are certain policies which force people to do things that they would otherwise not. It is compulsory for children to attend school; for restaurants to register with health authorities; for visitors to some countries to be vaccinated or innoculated; for motorists to take out third party insurance policies to cover innocent accident victims; for employees to pay social security contributions because they may not otherwise make provision for their old age.

The state may pass laws, or establish institutions, designed to affect the framework within which markets operate in order to improve their efficiency, their fairness, or both. There are many possible illustrations — for example, the laws governing the sale of goods, advertising, hire purchase contracts, patents, copyrights, compensation for loss of job, and so on.6 Institutions set up by the state to exercise influence on market behaviour include the Monopolies and Mergers Commission, the Restrictive Practices Court, employment exchanges, industrial and rent tribunals, training boards, and so forth.

We could continue at great length to give examples of the rules and regulations that have been introduced to try and remedy defects of particular markets. The only general comment an economist might make would be to emphasise that, in so far as there is any interference with the forces of supply and demand, one should look for effects similar to those discussed earlier in connection with price controls. This should by no means be taken to mean that any intervention is necessarily undesirable, but that it may need accompanying measures for the allocation of supplies as well, of course, as ensuring compliance.

State Control of Production and Distribution

There are certain economic activities where the market may be regarded as so inadequate for the production and distribution of goods and services that the government may decide to take them on itself. Such a decision may, of course, be made on purely political grounds, for example, when nationalisation is proposed because of dissatisfaction with the ethical basis of a capitalist system. Public co-operation may, however, be a solution for particular problems arising from market failure, leading to partial state ownership and control of sectors of the economy. It is, in fact, a common feature of the economies of many Western countries that public goods like lighthouses are operated by government agencies. State corporations in Britain run natural monopolies such as electricity and railways. The government also undertakes the provision of the armed forces, police, schools, hospitals and a variety of social services.

State control, it must be emphasised, does not, by itself, solve economic problems. They do not go away when an industry is nationalised. They are, however, put into a new context, in that allocation decisions are, to a greater or lesser extent, taken by government or its agencies instead of by private producers and consumers in the market. The need for appropriate output and pricing policies remains. The real cost of production need not be materially affected by changes in ownership.

State control may be of production and distribution or confined to either of these. For example, the government may wish in the case of health services to be supplier and distributor. Alternatively, in the case of the provision of motorways, the state may decide how much should be spent on them and where they should be located, while leaving the construction of the roads themselves to private businesses. The extent of desired involvement varies with circumstances and there is little general guidance that economists can offer on the matter. One consideration is, however, worthy of mention. It concerns the question of freedom of choice. A decision may have to be taken on whether consumers should be allowed to purchase for themselves goods or services similar to those provided by the state. This is, of course, an issue with heavy political overtones. For instance, should individuals be free to buy medical care at their own expense at higher levels than are available on the national health service? Or, to give another controversial example, should parents be allowed to buy, for their children, standards of education different from those in state schools? There can be no objective answers to questions like these. They are matters of personal opinion, though one relevant economic argument may be that competition may help maintain standards.

There is one final, and also controversial, economic aspect of state-provided services. How should their costs be covered? Many methods are possible, but the discussion can be simplified by first considering two extreme solutions: (1) services may be provided free and (2) those who use them may be charged for doing so. This is another area which runs into deep political waters, especially when charges for social services are under discussion.

Let it be emphasised that the real costs have to be borne by someone. Free provision simply places the burden on general taxpayers, instead of on consumers if charges are levied by use. The pros and cons of the alternatives must sensibly be weighed case by case. For goods which are clearly consumed collectively, there is no practical method of financing them other than from central funds. Defence expenditure on armies and equipment is an obvious case in point, where it is widely accepted that the cost should come from general taxation. No one seriously suggests, either, that the police can or should have their costs paid for by the individuals who use their services! However, the question of the proper way to pay for state education and health is much more controversial. On the one hand, are those who argue that free provision encourages abuse of the system. On the other hand, there are those who contend that charging discourages the use of services by those in greatest need. One can also identify intermediate cases, like the provision of motorways or bridges, where charges to cover the whole or part of costs may be levied on users but where the administrative costs of charging are not negligible. Arguments can only be sensibly assessed in the context of particular cases. One should add, moreover, that the proper price to charge is not necessarily that which just covers cost if there are important externalities present, giving benefits to those other than to direct consumers. (For instance, users of minor roads benefit from reduced congestion when a new motorway is constructed.)

The Choice of Policy Instruments

We conclude this chapter by putting forward a suggested approach to decision-making on questions of policy which appears logical. It involves a four-step procedure.

Step 1 Identify the general cause of market failure, that is, whether due to dissatisfaction with income distribution, market imperfections, time-lags, externalities, or paternalism.

Step 2 Identity the proximate cause of the situation deemed undesirable, that is, determine whether, for example, monopoly power is based on economies of scale or product differentiation.

Step 3 Identify the alternative policy instruments which could be employed to try and remedy the defect under consideration.

Step 4 Quantify all the costs and benefits of each alternative policy (including that of non-intervention), taking account of all side-effects and political practicalities.

The last step is a formidable one that may be extremely difficult and costly to carry out. However, unless some attempt is made to quantify, even approximately, the costs and benefits of alternative policies, it is hard to know which to select. No one should pretend that there exist identifiable optimum solutions to the problems of economic policy. Personal and political attitudes are unavoidable and there is usually too much uncertainty about the precise effects of different policies to allow full assessments to be made. The four-step procedure suggested above is supposed to be no more than a guide to clear thinking on policy alternatives. It certainly should not be taken to imply that the best solutions can be simply discovered.

One implication of the procedure deserves, however, to be amplified. Step 1 might be thought to indicate that it is possible to isolate a single cause of market failure in particular cases. This is unlikely. A market may fail for several interconnected reasons and it may be hard to unravel them. For example, consider the case for intervention in the housing market. Is it justified on grounds of income disitribution (that the poor cannot afford decent housing)? On grounds of paternalism (that people do not sufficiently realise the benefits that accrue from living in 'better' housing)? On grounds of imperfect competition (that there are monopoly landlords and builders who keep the supply down to push the price up)? On grounds of delays and time-lags (because it takes so long for a significant increase in the housing stock to materialise)? On grounds of external spillover effects (on neighbours living next door to families in 'substandard' housing)? It is easier to pose questions like this than to answer them. That is no reason, however, for not asking them at all, nor for failing to try and assemble whatever rudimentary evidence one can, to help in making sensible decisions. There is often a wide range of alternative policies available.

To continue with the previous example, suppose the main cause for dissatisfaction with the working of market forces in housing was that it was believed that the poor could not afford to pay for adequate accommodation. A first step would be to try to discover the income levels of families living in inferior housing. If it was found that they were indeed very poor, one might at least consider a policy which raised their incomes, but left them the choice of how to spend it in ways that maximised their satisfaction, given their varying needs and tastes. One could compare this policy with another which subsidised housing directly and which might perhaps be justified by the advantages accruing to the children of such families. Alternatively, the proximate cause of concern might have been a fear of monopolistic landlords. This, too, could be checked by sample surveys and, if confirmed, might suggest a policy of rent controls. It would then be necessary to consider side-effects, such as the possibility of a reduction in the supply of rented accommodation.

Equity Versus Efficiency

The consideration mentioned in the last sentence should remind us that policy instruments can have undesired side-effects. This may make choice difficult. It may be made more so because the goals of equity and efficiency may be conflicting ones. For example, the tax system may affect incentives as well as redistribute incomes. One often hears the argument that progressive taxes cause people on high rates of pay to work less hard. If true, this is an important consideration for policymakers. However, it must be pointed out that the evidence on the effects of high marginal tax rates on incentives is far from unequivocal. On the one hand, it appears that some people do work less hard when tax rates are increased. But, on the other hand, there are others who work harder, in order to earn the same pay net of tax as they did previously. In the present state of knowledge, therefore, it cannot be concluded that raising rates of tax on the community as a whole has incentive or disincentive effects on balance.

One might perhaps close with an admission. Attempts to achieve a perfect allocation of resources are doomed to fail. We might, therefore, better concentrate on trying to make improvements to present situations. Then, we might end up with an economy that is at least second rather than third, fourth or fifth best, or even worst!

Comparative Economic Systems

Economic policy has been discussed in this chapter in as detached a manner as possible. It should be emphasised, however, that any writings on this subject must reflect the personal opinions of an author. There is no better way to appreciate this remark than to read widely, which the reader is advised to do.

Policy recommendations can be seen as arising from basic political attitudes towards state intervention. Those who see great virtues in a freely working price mechanism stress the advantages it confers. Self-interest supplants government. The market is cheap and impersonal. Price is the same for every person who enters the market, regardless of sex, race or religious belief. The price mechanism works continuously, reflecting changes in supply or demand, while planning decisions take time to be put into effect. Moreover, the ballot-box provides only an infrequent opportunity for consumers to express approval or disapproval of what planners achieve.

Those who are less fearful of state intervention, in contrast, stress the causes of market failure — the long time prices take to work, the desirability of redistributing incomes, the prevalence of monopoly, and the divergences between private and social costs which result in an imbalance between private and public sectors, typified by too many cars and too large classes in schoolrooms.

There are obvious weaknesses on both sides. No one seriously argues that 100 per cent laissez-faire or 100 per cent state control is ideal for an economy. Indeed, it is perhaps remarkable how central planners in some communist countries appear to realise that prices can play an important role in a socialist state, without private ownership of the means of production. At the same time Western economies tolerate considerable interference in economic life. Britain has a mixed economy with private and public sectors, which may confirm that there is merit in both.

Notes: Chapter 10

1 Total costs for a single firm are BC times OB. They would necessarily be greater if the market was shared with one or more other firms. The reader can prove this for himself. Suppose the market was shared between two firms of equal size having the same costs. Average cost of each firm would be half OB times the vertical distance between the point on the quantity axis bisecting AB and the average cost curve directly above it. Total cost is given by the rectangle formed by this distance times output. If you measure the size of the total cost rectangles they must be greater than the rectangle OB times BC, representing the total cost of the single firm monopolist.

2 Not least because the sale of 'optimum' output (OB) at a price equal to marginal cost (BD) would involve losses (of CD per unit).

3 There is parallel here too with a basic issue of macroeconomic policy: that of the time for any self-correcting mechanisms in the economy to work to ensure full employment. (See above, Chapter 9, page 201.)

4 Note that the social optimum is not necessarily to reduce pollution to zero, but to a level where the full social costs are equal, at the margin, to benefits provided by the goods produced.

5 For a detailed discussion of government prices policy see Mitchell, J., Price Determination and Prices Policy (Allen & Unwin, 1978).

6 For a discussion of the links between economics and the law see Oliver, J. M., Law and Economics (Alien & Unwin, 1979).