Chapter 9

Economic Policy:

I Macroeconomics

The UK, in common with all modern countries, delegates to its government certain powers which influence many aspects of economic life. We shall examine in this and the next chapter the main reasons why this is so, referring in the process to some of the ways in which the British Government tries to exercise control over the economy. The reader should be warned in advance that this is the most controversial part of the book. Economists differ from each other in their policy recommendations for several reasons. They have different views on how the economy works, largely because the evidence is capable of varied interpretations. They disagree about the most efficient policy instruments that can be used to achieve given objectives. Finally, we must recognise that economists are also citizens and they differ on the appropriate goals to adopt because they have different political views on the kind of society they want to live in.1

The choice between alternative economic policies is an immensely complex matter. Reaching decisions on the best policy to adopt in any situation is, moreover, further complicated by the fact that even agreed policy objectives can conflict, in the sense that the closer we get to one target the farther we may find ourselves from another. For example, a distribution of income which society regards as equitable might have undesirable effects on economic incentives. If there were such a conflict, the question would have to be asked of the relative importance of the two goals. Or, to pose it more appropriately, we might think of a 'trade-off' between equity and incentives, so that a decision could be made about how much it would be worthwhile sacrificing of one for the sake of the other. Sometimes, there may be no choice. At other times there may be and an answer to the question cannot be given without involving political attitudes.

We shall look separately at the subject of macroeconomic and microeconomic policy formation in this and the next chapter. We begin with the former for no other reason that that it follows more naturally from Chapter 8.

The Goals of Macroeconomic Policy

The first need is to set out the principal goals of macroeconomic policy. Three primary targets are usually distinguished:

- Economic growth

- Full employment

- Price stability

A fourth goal, which is sometimes included, relates to the balance of payments. This may at times be of great importance, but it is, however, more appropriate to regard it as a secondary than a primary goal because it is sought after, not so much for its own sake, but because a country's balance of payments can act as a serious constraint on the achievement of one or more of the other goals.

(1) Economic Growth

The desire to achieve a high rate of economic growth sometimes appears to be almost the only fundamental target for a country to aim at. 'League tables' comparing growth rates of different countries are often constructed and simplistic conclusions drawn that the countries at the top of the league are, so to speak, winning some kind of race. It is certainly true that growth is usually accepted as a laudable objective, but the implication that the sky is the limit is hardly justified.

In the first place, economic growth is not wanted for its own sake but in order to raise living standards. In this respect the reader may remember that the growth rate of national income may not mirror precisely at all times the growth of living standards. The reasons were discussed at some length in Chapter 6 (pages 107—12) and will not be repeated here. It may be recalled, however, that it is necessary to take account of such matters as population changes, the distribution of income, leisure and other categories excluded from the national accounts. Moreover, it has to be recognised that there are costs of economic growth. Three major costs may be distinguished, (a) Growth is sometimes accompanied by an increase in economic 'bads', such as pollution and spoilation of the physical and social environment, (b) In so far as growth in future years requires capital investment in the present, it is likely to involve a sacrifice of present consumption in order that resources may be devoted to the production of capital equipment, (c) To anticipate a later conclusion, economic policies to promote economic growth may involve the sacrifice of other objectives, such as price stability or a more desirable income distribution.

A final aspect of the nature of the goal of economic growth that must be mentioned in any discussion of economic policy is that there is no known and certain way to promote growth, it is easy enough to state the obvious — that the national income will rise faster the greater the supply of all the factors of production and the more efficiently they are employed. It is a good deal harder to find ways of implementing it. How does one make managers more efficient or make labour more productive, for example? Is competition important? What is the quantitative contribution of education and training? These are leading questions, to which even leading authorities are uncertain of the answers.

(2) Full Employment

The objective of keeping unemployment low is so widely regarded as being desirable that politicians almost always pay at least lip service to it. Yet as a goal it is almost inevitably a rather vague one.

Quite apart from the fact that every country has some 'unemployables' who are incapable of work, no one seriously believes that the rate of unemployment either could, or even should, be reduced to zero. A certain amount of temporary unemployment is inevitable if an economy is to grow and change its structure. Frictional and structural unemployment are the names given by economists to what are the minimum levels that have to be tolerated in the short and long run if workers and firms are to shift jobs and industries as technological and other changes call for the expansion of some sectors of the economy while others are contracting.

The unemployment target is often expressed as a percentage of the total labour force out of work. Such a figure can be misleading because the total numbers are ambiguous. They are commonly restricted to those persons actively seeking work (and registering at employment exchanges for the purpose). But this number is likely to vary with the state of the labour market. When unemployment is high, for example, some potential workers, married women for instance, may not bother to register.

An alternative target runs in terms of the ratio of the numbers of unemployed to the numbers of job vacancies. If the only unemployment is structural, this ratio should in the long run be approximately equal to unity, though if expanding sectors are less labour-intensive than contracting ones the short-run ratio may be higher. If there is a deficiency of aggregate demand in the economy the unemployed should outnumber the vacancies, and vice versa. Even equality between vacancies and job seekers may be unsatisfactory for the individuals concerned. If there are 1,000 unemployed shipbuilders on the Clyde, it is no comfort to know there are vacancies for 1,000 shorthand typists in London. Government policy to improve job and geographical mobility, both of workers and of industry, is usually undertaken for this kind of reason.

(3) Price Stability

Curiously enough there is nothing obviously and inevitably unsatisfactory about price instability itself. Yet inflation, which is a particular form of price instability, has in popular belief come to be thought the scourge of our times. Is there any substance to the belief?

The first thing to be said is that a kind of price instability is regarded, similarly to a certain degree of unemployment, as being part of the cost of economic advance. Prices act as signals reallocating resources as technological and other underlying factors change and a degree of variation in prices is, to an extent, helpful.

The price instability that causes concern, even alarm, is not, however, of relative price movements in individual sectors but of the general price level. It is inflation — creeping, persistent, accelerating — that is the butt of current onslaught. On the face of it we might wonder why? We argued earlier that if prices doubled overnight and everyone's income and assets doubled at the same time, real underlying economic circumstances need not have changed at all.

The point of repeating this illustration is that it focuses attention on why circumstances are not precisely the same when the price level changes. There are three principal reasons. The first two concern the allocation of resources and the third, the size of the national income.

Consider first the distribution of income before and after the doubling of the general price level. It is surely most unlikely that every single person would receive twice as much as he did before. Some individuals would perhaps only get a 50 per cent rise while others got 150 per cent or more. Although total personal income doubled, there would be gainers and losers. In inflationary conditions, this is what generally happens. We can identify the gainers as those whose incomes keep ahead of prices and the losers as those whose incomes lag behind. At different times the gainers and losers may vary, but the former include those with substantial market power, such as businesses selling goods where demand conditions facilitate upward price adjustments, or labour in strong trade unions. Individuals whose incomes are fixed in money terms, for example, widows living on annuities or recipients of state security payments which are not revised upwards to allow for rising prices, are obvious losers.

Inflation affects the value of assets as well as incomes. Holders of cash balances lose, by definition, while owners of assets the prices of which rise faster than the general level are gainers. An obvious example of the latter is houseowners. Between 1970 and 1979 average house prices roughly quadrupled, while the index of retail prices only tripled. Creditors tend iso to lose, relative to debtors, in so far as debts fixed in money terms are easier to repay with depreciating currency.

Inflationary circumstances distribute resources in ways other than would occur if prices were steady. This is particularly important when price rises are substantial or accelerating and when uncertainty about future inflation rates is great. Lending becomes risky, especially for long periods. So, too, does borrowing in the face of uncertainty about future costs of production. Productivity may then be adversely affected. Inflation stimulates the acquisition of assets like works of art, coins, stamps and wine, rather than productive investment, as individuals search for safe hedges against rising prices. The result of inflation may therefore be to impede economic growth and affect total national output.

A complete answer to the question of whether inflation really is the scourge it is often accused of being must, therefore, take account of both its real and its distributive consequences. We cannot make any generally useful assertions about whether the latter are equitable or not any more than we could conclude that the redistribution that would be involved if inflation were halted overnight would or not be fair. We should minimally know the financial circumstances of gainers and losers to offer an opinion; even then we should find it difficult to avoid making political value judgements. It must be remembered that continuing inflation tends to become accepted as a fact of life, with the result that arrangements are made by which an increasing number of incomes are more or less automatically adjusted to the cost of living.

The argument that the real rate of economic growth is held down by inflation (which also affects a country's international competitiveness) is a potentially serious one. In cases of 'moderate' inflation the issue is debatable. When the rate of inflation is accelerating, there is less doubt about it. Moreover, it is necessary to take notice of an extreme case. Occasionally the rate of increase in prices has reached runaway proportions, as in Germany after the First World War and Hungary after the Second. When such hyperflation, as it is called, sets in, prices jump astronomically, even hourly. All faith in the currency is lost and people resort to barter, with commodities like cigarettes and coffee assuming money's role as a store of value. This can bring the economy to a state of virtual collapse and call for draconian measures to restore confidence.

In cases where the rate of inflation is moderate and economic growth not affected, we may conclude that a stable price level might be preferable to one that was rising, but that there is no compelling reason for giving the conquest of inflation absolute priority over other objectives of economic policy. The issue is perhaps best put as a question asking what are the benefits of reducing the rate of inflation by a certain amount and what are the costs, in terms of sacrifices of other objectives which might have to be borne to achieve it. This leads us to consider whether there are any 'trade-offs' whereby inflation can 'buy' any economic advantages. This is one of the central problems in macroeconomic policy of the present day.

Unemployment Versus Inflation

The expression 'trade-off' is no more than an application of the notion of opportunity cost to economic policy. When economists talk about a trade-off between inflation and unemployment, they imply that there may be a conflict of objectives and that a choice may have to be made between them. In other words, a reduction in inflation could 'cost' more unemployment and vice versa.

The first question that must be asked is whether there is or is not such a trade-off at all. Discussion of this crucial issue cannot be conducted without reference to the work of the New Zealand economist, the late A. W. Phillips, which has been so influential that some simple facts to which he drew attention have become known as the 'Phillips curve'.

Phillips was interested in the historical relationship between wages, prices and unemployment in Britain over the period 1861 to 1957. The close association that he observed between wage rates and unemployment is illustrated by the curve PC in Figure 9.1. The statistics suggested

Figure 9.1 The Phillips curve (1861-1957).

Source: Phillips, A. W., 'The relation between unemployment and rate of change of money wage rates in the UK, 1861-1957', Economica, n.s., vol. XXV, no. 100 (1958).

that the strength of the excess demand for labour explained both the level of unemployment and the rate of inflation. They also implied that, for policy purposes, a trade-off existed and that it was a fairly stable and predictable one. As can be seen from the graph, unemployment tended to be low when price increases were high and vice versa. Interest attaches to the point where the Phillips curve cuts the horizontal axis around 5½ per cent, which is the unemployment rate at which price stability would appear to occur. It should be added that this result carries with it the implication that about 5½ per cent unemployment is the rate to ensure stability in wages as well as prices, if there are no increases in productivity. Historical trends show, however, a tendency for productivity to rise over time. The conclusion should be amended to allow for this. Assuming an annual average increase in productivity of about 2 per cent for example, price stability could be maintained if wage increases were held around 2 per cent per annum and the associated unemployment rate became a little under 2½ per cent.

Work along the lines of Phillips's study was soon under way in other countries, where reasonably stable relationships between inflation and unemployment were found. However, after the mid-1960s the nature of the relationship appeared to change. Ten years later, predictions from the old Phillips curve differed so greatly from the facts that the curve began to be described as dead. The observed associations between the rate of change of prices and the level of unemployment for some recent years are shown in Figure 9.1 as single points marked with dates. They are well off the original curve. To show the utter failure of history to repeat itself, one can even refer, for example, to the year 1974, when unemployment was standing at 2½ per cent and wages were rising at about 30 per cent (so far off the curve it cannot be shown on this graph). According to Phillips's calculations wages should have been rising by no more than 5½ per cent at this level of unemployment.

What had happened to the Phillips curve? Had it disintegrated, or were the recent observations points on one or more new Phillips curves to the right of the old, that is, had the curve shifted, temporarily or permanently?

It is an important question. Disintegration would imply the disappearance of any trade-off between unemployment and inflation. Shifting, in contrast, would imply a trade-off, but a different one — specifically, that price stability could be bought only at the cost of higher unemployment levels than previously.

The new observations relate, of course, to the period of the 1970s discussed previously, when high unemployment coexisted with high rates of inflation (see pages 120—1). A great deal of work has been done to try and identify the causes of the changes in the situation and effectively, therefore, to discover what happened to the Phillips curve. Numerous theories have been put forward to explain the new relationship. It has been suggested that the higher levels of employment associated with given rates of inflation might be due to increased trade union power, higher rates of social security payments and the narrowing of wage differentials, which price unskilled workers out of the market.

The Role of Expectations

One explanation requires special attention. It calls for the introduction into the analysis of the expectations of the community about the course of future rates of inflation.

The proposition is that the association that Phillips found derived from experience of periods when the general level of prices was fairly stable. In an inflationary age, in contrast, it is argued, people do not ignore the fact that prices are rising. They come to expect them to continue to do so and they incorporate their expectations of future price movements into their behaviour. The argument applies both to businesses and to labour. Consider the attitude of trade unions to wage negotiations (and assume for simplicity that there are no changes in productivity). If unions expect the price level to rise by, say, 10 per cent, they need to achieve a 10 per cent wage increase to maintain the standard of living of their members. If businesses have the same expectations, they will also expect to be able to raise prices by 10 per cent. They will, therefore, be prepared to grant 10 per cent wage increases. A 10 per cent inflation rate ensues.

Price expectations can be incorporated into the type of diagram used by Professor Phillips by the expedient of drawing, not one, but a set of, short-run Phillips curves, each of which corresponds to a belief held at a particular time about future movements in the general price level. The original Phillips curve assumes that the price level is not expected to change (dubbed therefore 'naive' in an inflationary age). It is PC1 in Figure 9.2. Each of the other curves is drawn on the assumption of different price expectations, which are built by labour into wage bargains in order to maintain constant real wages in the face of rising prices. PC2, for example, is the curve pertaining to an expected inflation rate of 10 per cent. It is the curve that shows the relationship between inflation and unemployment when the community expects inflation to run at a 10 per cent rate. PC3 and PC4 are the short-run Phillips curves corresponding to 20 per cent and 30 per cent inflationary expectations.2

The diagram may be used to illustrate the situation described above of continuing 10 per cent inflation. If the community expects the price level to rise by 10 per cent, then the Phillips curve applicable to its behaviour is PC2. Suppose that the economy is at full capacity output, which corresponds to a level of frictional and structural un

Figure 9.2 Shifting short-run Phillips curves.

employment equal to OL. Labour seeks a 10 per cent wage increase to keep real incomes constant, because it expects prices to rise by 10 per cent, and both take place. Let us draw a vertical line through L (LL') to show the level of unemployment associated with full capacity output, but which, as we shall see, might be associated with a range of rates of inflation. The economy will be in equilibrium at B in the diagram, where the short-run Phillips curve (PC2) cuts the line LL'. This position is consistent with expectations of the price level rising by 10 per cent and with those expectations being realised. Indeed, if expectations continue unaltered, the economy may rest at an equilibrium position, such as B, with continuing inflation of 10 per cent. If no outside influences to act as disturbances occur, one might expect such to be the case. Expectations mav not unreasonably be related to oast experience.

Note, however, that all the points of intersection of short-run Phillips curves with LL' are positions where expected and actual inflation rates are the same. Each shows a different rate of price increase. The economy could be at rest at any of the points B, C or D with inflation proceeding steadily at the rate corresponding to the Phillips curves PC2, PC3 or PC4. It could even enjoy equilibrium at L, representing full employment and price stability.

Accelerating Inflation

The analysis of the previous section provides a possible explanation of inflation proceeding at a continuous steady rate. However, the experience of recent years has included periods of accelerating inflation. The argument can be extended to this situation by the addition of an assumption that a policy is adopted by the government to try and bring the level of unemployment below that which is consistent with zero inflation (actual and expected), that is, OL.

Let us turn again to Figure 9.2 and start with the economy at position L, representing full capacity output, an unemployment rate of OL and, therefore, both price and wage stability. Suppose, now, that the government is not satisfied with the unemployment level OL and embarks on a policy of expansion of aggregate demand in an attempt to get unemployment down to OM.

Since neither business nor labour expects, as yet, prices to rise, the economy may move along the short-run Phillips curve to position A and unemployment may decline (to OM). However, the economy is, by assumption, at full capacity output. Therefore, the expansion in aggregate demand cannot bring about a rise in real income, but only in the price level. As soon as inflation starts, people's expectations of continued price stability are liable to be revised. If we suppose that the rise in prices is 10 per cent and that rate is expected to persist, then labour will need to bargain for 10 per cent wage increases in order to maintain real wages. The relevant Phillips curve is no longer PC1, but PC2 (expectations of 10 per cent inflation). The economy moves to positional A'.

If we assume that the government continues to try to keep unemployment down to OM, it will need to induce a further expansion in aggregate demand to enable business to pay the wage increases demanded by labour (which were not expected). The same argument applies again, that output cannot be raised beyond full capacity, so the effect of the increase in aggregate demand can only be seen in further rises in the general price level. Let us suppose that this is another 10 per cent, so that prices rise 20 per cent above the original level. When this happens, it will become apparent to trade unions that wage increase of 10 per cent was insufficient to maintain constant real wages. They therefore bargain for a further 10 per cent wage rise, making 20 per cent in all. The short-run Phillips curve, PC3, corresponding to inflationary expectations of 20 per cent, then comes into play (replacing PC2). The economy moves to position A". But this is not a position of equilibrium and the level of unemployment OM can only be held if aggregate demand is yet further expanded. Such an expansion would cause the price level to rise yet again, bringing forth expectations of even higher inflation. If labour continues to bargain to maintain real wages, the Phillips curve shifts upwards once more, and the economy moves towards A"'. The time path of the economy, when the government follows a policy which allows aggregate demand to expand in order to keep unemployment down to OM, can be viewed as follows: ever-upwards movements vertically along MM', with the short-run Phillips curves shifting also upwards as expectations of accelerating rates of inflation replace each other.

The critical elements in the explanation of accelerating inflation described in the previous paragraph are (1) the incorporation of price expectations into bargaining over real wages and (2) the policy of trying to hold the level of unemployment below that which is associated with full capacity output and price stability. The analysis follows from the assumptions. It is another matter whether it is also a valid description of economic behaviour in this, or any other, particular country. On this question opinions vary. Figure 9.2 can, however, aid understanding of three possible situations: (1) accelerating inflation corresponding to upwards movements along MM', as just described; (2) a choice of stable rates of inflation at different points on LL' at full capacity output and unemployment equal to OL (including zero inflation at L); and (3) a choice between unemployment and inflation involving a movement along a Phillips curve.

The key question is which of the three alternatives represents the real situation? It is one of fact, but there are many opinions on the matter. We may illustrate two extreme views with the use of Figure 9.2. The school of thought which believes that a trade-off exists assumes that it is possible to move along a Phillips curve, sacrificing price stability for lower unemployment levels, or vice versa. Such a possibility is denied by those who argue the opposite view, that the Phillips curve shifts upwards as expectations are revised in the light of experience of inflation. For them, the long-run Phillips curve is vertical, along LL' (or possibly MM' with continued expansion of aggregate demand). There is no possibility of a trade-off according to this argument. One simply cannot reduce unemployment in the long run without accelerating inflation.3

An intermediate position is a trade-off possible in the short run but impossible in the long run. This was, as a matter of fact, described at the start of this section on accelerating inflation, where the economy started at position L and moved, in the short run, to the left along the Phillips curve PC1, as aggregate demand was expanded to reduce unemployment, but entailing higher prices. It was attainable in the short run only until the Phillips curve shifted to PC2 as a result of incorporating revised expectations about the future of the price level. Without further expansion of aggregate demand, equilibrium would have settled at B, with continuous 10 per cent inflation of wages and prices.

The importance of the previous analysis for macroeconomic policy is considerable. If there is a real possibility of trade-off, in the short or in the long run, between unemployment and rising prices, then there is a choice facing the government about how much inflation it is worth tolerating in order to secure a given level of unemployment. However, if no trade-off exists, there is no point in trying to keep aggregate demand at a level that keeps unemployment below that associated with full capacity output, unless one is prepared to tolerate accelerating inflation. In the long run even this may prove impossible.

Unemployment at Full Capacity Output

The conclusion reached in the previous paragraph hinges to a considerable extent on the meaning given to the phrase 'the rate of unemployment compatible with price stability and full capacity output'. This rate has been termed the 'natural' rate of unemployment, but it may be defined as the rate at which there is no unemployment caused by a deficiency of aggregate demand; that is, all unemployment is frictional or structural.

From a policy point of view, concern is minimal if this level of unemployment associated with full capacity output is relatively low and stable. However, if it is high, and especially if it is rising, problems arise because, by definition, frictional and structural unemployment is not curable by expansion of aggregate demand. In practice, it is difficult to know what the level of structural unemployment is that cannot be cured by expansionary policies. The evidence is not easily interpreted, but there are reasons for believing that the rate may have been rising in recent years as a result of technological advance. This would follow if expanding industries have been less labour-intensive than contracting ones. More unskilled workers (or workers with the wrong skills) would then have been released than could be absorbed by capital-intensive new industries.

In circumstances of this kind, the most effective means of reducing the level of unemployment would lie in the direction of policies aimed at increasing labour mobility, for example, retraining programmes and subsidies in support of geographical mobility, when expanding and contracting sectors are highly localised far apart from each other.

This is a very controversial policy area and an emotive one because of the human misery that is associated with heavy unemployment. The advocates of maintaining high levels of aggregate demand argue that it is worth risking a certain amount of even accelerating inflation to keep the economy right up to full capacity output so that new industries are continually encouraged. Those opposed to this policy are not necessarily any less concerned with the social costs of high rates of unemployment. They press the more strongly for policies related directly to increasing mobility simply because they regard this, structural, unemployment as being unalterable by the expansion of aggregate demand; that is, they do not believe in the existence of a long-term trade-off whereby the government can 'buy' less unemployment with higher inflation.

We cannot pursue the matter further here. There are distinguished economists on both sides of the fence as well as many adopting intermediate positions. It is, however, a relevant point of departure for the examination of the alternative instruments of macroeconomic policy between which governments can choose.

The Instruments of Macroeconomic Policy

We have deliberately chosen to lead into the discussion of the alternative instruments of economic policy on a controversial note in order to emphasise that a major reason why policy recommendations among economists differ is disagreements about some important aspects of exactly how the economy functions. Different schools have their own ideas of the determinants of economic behaviour and prescribe accordingly. Until we improve our understanding of the nature of certain economic forces, we have to live with this state of affairs.

With this realistic, if discouraging, opening, we may consider that the authorities have a number of alternative instruments that can be employed to achieve the macroeconomic targets of economic growth, full employment and price stability. Three groups are usually distinguished: fiscal, monetary and prices and incomes policies.

(1) Fiscal Policies

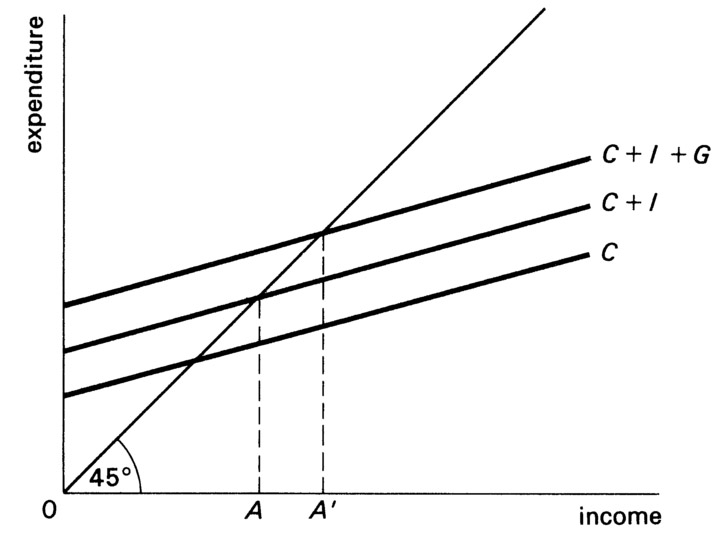

Fiscal policy is the term given to measures which aim at the control of aggregate demand by budgetary means. It developed from a Keynesian view of how the economy works, which was described in Chapter 7. Governments using fiscal policy to counteract depressions, for instance, adopt budget deficits, increasing spending and/or reducing taxation to add to overall purchasing power. Figure 9.3 illustrates the technique of fiscal policy to counteract a depression due to a deficiency of aggregate demand. Government expenditure is added to the consumption and investment expenditure of the private sector. Aggregate demand is pushed up from C + I to C + I + G leading to a rise in

Figure 9.3 Fiscal policy.

income, through the action of the multiplier, from OA to OA'. In boom conditions, fiscal policy takes the form of budget surpluses to reduce the pressure of total demand.

Fiscal policy may call for discretionary decisions to alter the size of government income and/or expenditure. But it is important to note that most tax systems contain some so-called 'built-in stabilisers'. For example, progressive income taxes have the property that their yield automatically increases as income rises and vice versa. It is true that some other taxes work differently, for example, those fixed in money terms (like TV licences and the duty on alcohol and tobacco). However, it has been estimated that the net effect of inflation is to raise government receipts in the UK. This is known as 'fiscal drag'.

In addition to changing direct demand by the government, fiscal policy also includes budgetary changes aimed at altering private expenditure on consumption and investment by varying the structure of the tax system, for example, by shifting tax rates on lower and higher income groups, who tend to save different proportions of their incomes.

We shall return to consider the merits and demerits of fiscal policy after we have dealt with alternatives. It may be said now that fiscal policies were extensively used in the earlier postwar years, but that it is debatable whether their effects were on balance stabilising or destabilising. The reason for the debate is largely that it is difficult to know how the economy would have behaved had there been no fiscal intervention by the government.

(2) Monetary Policy

Fiscal policies are particularly suitable for dealing with depressed output and employment in times of falling (or stable) prices. They have been criticised as being inapplicable to inflationary periods and, in particular, to occasions characterised by the coexistence of high inflation and high unemployment in the 1970s. The monetarist school of economics, whose views of the way the economy works underlines much of Chapter 8, developed largely as a reaction to what were regarded as the deficiencies of Keynesian emphasis on fiscal policy.

Monetary policy attempts to influence aggregate demand, employment and the price level by controlling the quantity of money and interest rates. The institution which is used to operate monetary policy for the government is the central bank — in Britain this is the Bank of England. Its activities are to a considerable extent technical and the reader is advised to seek full explanations of these elsewhere. However, the mechanism is important and we must briefly explain the basic principles by which a central bank can implement monetary policy for the government.

It will be recalled, from Chapter 7, that the main component of the money supply in a country consists of the deposits of commercial banks. It will also be remembered that these banks keep to a safety rule that requires them to hold a certain proportion of their assets in liquid form, described as 'cash'. It must now be added that the commercial banks' cash base includes balances in accounts at the central bank. These are available for use (in the same way as are the commercial bank deposits by individuals) to settle their debts to other banks, to members of the public and to the government.

The central bank is able to exert pressure on commercial banks' lending activities (and, therefore, on their deposit-creating powers), in so far as their liquid cash base can be varied. One of the ways of doing this is known as 'open market operations'. This is a technique whereby the central bank buys or sells securities on the open market. If, for example, it is desired to reduce the supply of money, the central bank sells securities. These are bought by members of the public, who pay for them by writing cheques on their bank accounts in favour of the government. This has the effect of reducing the size of the commercial banks' balances at the central bank, that is, their cash base. It therefore depresses their cash ratio and, if this was held at the limit of the safety margin, will put pressure on them to make fewer loans. Bank deposits therefore tend to fall. The opposite procedure is adopted if it is desired to increase the quantity of money. The central bank then buys securities on the open market, adding to the cash base of the commercial banks.

The Bank of England

The way in which the Bank of England controls the money supply in this country is a good deal more complicated than that implied by the simplified process described in the last paragraph. A major reason for this is that the commercial banks hold more than the two kinds of assets, cash and loans, implied in the illustration. Their assets cover a wide range of financial securities of differing degrees of liquidity (and profitability). They include some very highly liquid loans made 'overnight', or 'at call', as well as others like Treasury Bills which are short term government securities, repayable three months after issue. The commercial banks maintain what they regard as balanced portfolios of assets and the fact that they hold those of different kinds suggests an alternative technique of monetary control which is employed. Certain of its liquid assets can be specified and the banks required to maintain a minimum ratio of them to their total deposits.4

Other techniques of monetary policy are used in this country. Calls are made for the banks to place deposits in frozen accounts at the Bank of England. These are known as 'Special Deposits' and may be altered by the Bank from time to time. Alternatively, the banks may be asked, formally or informally, to restrict their lending operations in periods of monetary restraint.

All the policy instruments described so tar are related to control or the quantity of money directly. They may also, however, be directed towards interest rates, which may influence spending. For instance, an increase in the money supply might succeed in pushing the rate of interest downwards, thereby encouraging investment (and perhaps even consumption) expenditure. The opposite consequences for interest rates might follow if the quantity of money were decreased. The Bank of England can also try to influence interest rates directly in a number of ways. The best-known of these makes use of what is called the minimum lending rate (MLR), the rate of interest at which the Bank is always prepared to make loans to City institutions. When this policy instrument is used, as a matter of convention, changes in MLR announced by the Bank of England tend to filter quite quickly through to other market rates of interest.

Economists who favour monetary rather than fiscal policies to control the economy stress the inadequacies of the latter. They are inclined to view aggregate demand as responsive to monetary forces, both to the quantity of money and to the rate of interest, and they are sceptical of the power of fiscal policy to deal with the twin aims of full employment and inflation.5 Special criticism is given to the effects on the private sector of fiscal policy which takes the form of budget deficits. The so-called 'crowding out hypothesis' is a contention that increases in government expenditure tend to push up interest rates and, as a result, merely succeed in replacing private expenditure which is, as it were, crowded out. An associated criticism is that government borrowing to finance expenditure in excess of taxes is inflationary. Attention is directed to the public sector borrowing requirement (PSBR) which can increase the liquidity of the banks and feed inflationary increases in the money stock.6 All this implies that the Keynesian multiplier analysis (see above, pages 139-43) may exaggerate the effect of fiscal policy on real national income if a part is reflected only in rising prices.

(3) Prices and Incomes Policies

Economists of what might be described as a middle-of-the-road school believe that both fiscal and monetary policies should be used in pursuit of the economy's macroeconomic goals. Some hold that a prices and incomes policy can provide useful support. This applies particularly in cases of cost inflation. But it is also thought that such policies could influence inflationary expectations and, in the short run at least, temper any accelerating tendencies.

Prices and incomes policies set targets, or guidelines, for price and wage increases designed to reduce inflation. At the most ambitious level they may aim to keep the growth of money national income in line with productivity. If trade unions and businesses can be induced to lower expectations about future inflationary rates, it may be argued, this could ease the task of controlling the money supply without adversely affecting either output or employment.

The evidence of the success or failure of past attempts by UK governments to set guidelines for wage and profit increases and maximum prices for products is that they have been more successful in the short run than in the long run. Pressure on wage rates tends to build up while income policies are in force, only to be released, sometimes with a bit of a bang, later on. Such policies also have other drawbacks. For trade unions, they interfere with the process of free collective bargaining. They also tend to affect wage differentials, in so far as lower paid workers are treated relatively favourably and skill premiums fall. The last effect may also be seen as indicating a distorting influence on the way in which prices serve as resource allocation devices. If relative prices are held more or less constant, the price mechanism is impeded in its allocative function of directing resources into their most profitable uses. Finally, it should be added that total enforcement of prices and incomes policies is difficult, if not impossible, to achieve. Black markets are encouraged by maximum price controls and individual groups in strong bargaining positions tend to be treated as 'special cases'.

The Balance of Payments

Before turning to discuss the controversial issue of choice between policy instruments, it is necessary to refer to the balance of payments, which was mentioned earlier as sometimes acting as a constraint on a country's macroeconomic policies.

We learnt, in Chapter 6, that the balance of payments is an account of the international transactions made between the residents of a country and the rest of the world over a period of time. These transactions comprise payments and receipts for visible and invisible imports and exports and flows of funds for investment. It is important to examine the principal factors on which the size of these flows depends. Three determinants may be distinguished: (1) incomes, (2) prices and (3) rates of interest.

The influence of each of these determinents on the balance of payments may most simply be explained in the context of a world in which there are only two countries. Let us call them H, standing for the home country, and R, standing for the rest of the world. First, changes in incomes affect the balance of payments because a part of income is normally spent on imports. Consider the position from the viewpoint of country H. If incomes rise (or fall) in H, its residents will tend to spend more (or less) on imports. If incomes rise in R, on the other hand, this carries the implication that foreigners will buy more goods and services from H, whose exporters thereby benefit from increased sales.

Secondly, relative prices affect a country's balance of payments in so far as demand and supply of internationally traded goods are responsive to price changes. If, for example, inflation is proceeding more rapidly in H than in R, this means that H's general level of prices is rising relative to that of R, making its exports and its domestically produced goods less competitive with R's.

Thirdly, relative interest rates affect the flows of funds for investment purposes on the capital account of the balance of payments. If rates of interest in H fall relative to those in R, funds will tend to flow from H to R in search of the highest rates of return.

The effect of relative prices on the size of trade flows needs further elaboration. In so far as a rise in the price level in H causes the volume of exports to fall, it does not follow that their value will also be lower. The value of exports is price multiplied by quantity (p x q). The reader will recall that the effect of a fall in the price of a good on total outlay by consumers depends on the elasticity of demand for the product. The same is true of the value of exports and imports after reductions in their prices. In order to know the balance-of-payments effect of relative price changes, we need information on the elasticities of demand for traded goods. The numerical values of such elasticities are, of course, empirical matters. Provided the elasticities are, however, large enough, changes in relative prices will lead to changes in the values of imports and exports in the same direction as volume changes. If this is in fact the case, it follows that relatively more rapid inflation in H than in R would lower the values of H's exports and increase the value of its imports, thereby tending to bring pressure on H's balance of payments.

Exchange Rates

It is necessary to add an important qualification arising from the fact that each nation values its goods and services in terms of its own national currency. There is, then, a question of the rate of exchange between currencies. £1 may sell, for example, for $1.00, $1.50, $2.00, or whatever the rate of exchange happens to be. Since the rate of exchange is a price, we should not be surprised to learn that the dollar-sterling rate is liable to be affected by the supply and demand for dollars, that is, the quantities offered and demanded at different exchange rates.

Let us continue the same example and assume that H's currency is sterling and R's is dollars. We can identify the sources of supply and demand for dollars to include the following. The demand for dollars comes from importers in H, who need foreign exchange to buy R's exports. The supply of dollars comes from exporters in H, who wish to convert the proceeds of their sales to R into their own currency (pounds).7

We must now reconsider the effects of a rise in the rate of inflation in H when the rate of exchange is brought in as a variable. The rise in prices in H relative to R is in domestic prices, expressed in sterling. It will not necessarily be reflected in prices converted into dollars. This depends on the sterling—dollar exchange rate used for conversion. The rate may be unchanged or variable. If it is fixed, domestic and foreign prices move together. Any change in the sterling prices of H's imports or exports will be accompanied by exactly equivalent price changes in terms of dollars.

The rate of exchange may, however, be allowed to vary with changes in the supply and/or demand for dollars. If so, we must examine the way in which these forces affect the exchange rate. Let us look, first, at the effect on H's exports. The fall in demand for H's exports following their price rise means a fall in demand for sterling to pay for them. Ceteris paribus, lower demand tends to bring price down. The price of sterling on the foreign exchange market is the number of dollars it is worth. Hence a fall in its price simply means that it is worth fewer dollars. This can be described as a downward movement in the exchange rate, or a devaluation of sterling. The argument can be clarified with an example. Suppose H exports cars priced at £4,000 each. When the exchange rate is £1 = $1, the dollar price of a car, for importers in R, is $4,000. Assume that inflation raises the price of H's cars to £5,000 each. The dollar price will change by an amount depending on the sterling—dollar exchange rate. If the value of sterling falls to £1 = $0.80, the car would still be priced at $4,000.

The supply and demand for foreign exchange can, therefore, affect the size of currency flows through variations in the exchange rate. Such movements may offset changes in domestic price levels in different countries — that is, the rate of exchange can act as an equilibrating force.8 In our example, relatively rapid inflation in H tends to make exports less competitive, but the devaluation of sterling tends to offset this price disadvantage and thereby helps maintain, or restore, equilibrium on the balance of payments.

There are, moreover, similar forces acting on the import side. Inflation in H makes foreign goods relatively cheaper and domestic consumers tend to buy more imports in consequence. However, devaluation of sterling tends to counteract the relatively lower dollar price of imports, making foreign goods dearer in terms of sterling.

Provided the elasticities of demand9 are great enough and other conditions are favourable, the rate of exchange can maintain equilibrium in currency flows and automatically offset disturbances which would put the balance of payments of a country under pressure. However, freely fluctuating exchange rates may be considered undesirable. This is, in fact, one of the reasons why the balance of payments has been described as sometimes acting as a constraint on domestic economic policy. Countries may take steps, alone or in collaboration with others, to stabilise their exchange rates. Indeed, internationally agreed fixed rates of exchange operated for many years (see below, pages 198—9).

Exchange rate stability has been considered desirable for a variety of reasons, including questions of national prestige. But a major objection to very volatile exchange rates is the fear that they might inhibit international trade in goods and services. An exporter who is worried that the rate at which he can convert foreign earnings into his own currency might move unfavourably, for example, may perhaps decide not to export at all.

Capital flows

The argument has a certain validity.10 Exchange rates have occasionally passed through periods of great volatility, such as when there have been runs of so-called 'hot money' away from a country in which confidence has suddenly dropped. Heavy selling of a currency tends to lead to large falls in its exchange rate. We should look into the capital account of the balance of payments for sources of large changes in the supply or demand for foreign exchange. As mentioned earlier, there we find flows of funds for investment seeking the highest return on capital. Such flows are sensitive to interest rates in the money markets of different countries. They are also liable to be affected by expectations of movements in the rate of exchange itself. If, for example, dealers anticipate that the value of sterling vis-à-vis the dollar is likely to fall, they tend to sell sterling and buy dollars before the devaluation takes place. Such a switch of funds would, ceteris paribus, bring about the very devaluation expected. Anticipation of a rise in the value of sterling could have the opposite effect.

Speculation can be soundly based, reflecting expert views on the basic soundness of an economy, the likely future course of inflation, productivity and international competitiveness, and so on. It may also, however, be based on unreliable, flimsy evidence or political fears. Panic can occasionally set in and lead to large-scale flights of short-term capital away from a currency, putting immense pressure on its exchange rate and causing serious economic consequences. This is the type of instability that governments particularly try to avoid by insulating the exchange rate from the free play of market forces.

Balance-of-Payments Policies

We may now return to the policy question with which we began. The reason why the balance of payments can act as a constraint on domestic economic policy is that countries try to ensure that international currency flows are kept roughly in balance, at least over a reasonable period of time. This implies the necessity to prevent any sustained reduction in the flow of receipts, relative to payments, for any purpose which would depress the exchange rate. We may distinguish four basic policy options for the government of a country under balance-of-payments pressure: (1) use up reserves of foreign exchange and/or obtain loans from abroad, (2) take action designed to alter domestic incomes, prices and rates of interest, (3) use the exchange rate as a corrective mechanism and (4) intervene directly in international markets.

(1) Use of Reserves and Foreign Loans

The first alternative is to use up reserves of foreign exchange and seek loans from other countries (and international organisations), thereby increasing the supply of foreign currencies to offset a downward pressure on the exchange rate. These can be no more than relatively short-term solutions. Reserves are limited and foreign loans will not be indefinitely forthcoming, unless other action is also taken.

(2) Deflation

The second set of methods is aimed at domestic incomes, prices and interest rates. A country suffering from balance-of-payment pressure would be called upon to reduce aggregate demand, lowering incomes and, therefore, the demand for imports. It would also try to lower its domestic price level in order to promote the sale of exports and to make home production more competitive with imports. Finally, it could also seek to raise the rate of interest in order to attract flows of capital into the country in search of higher earnings. Deflationary fiscal and monetary policies may aid in bringing down incomes and prices and in raising interest rates, but they are likely to be resisted internally in so far as economic growth might be inhibited and if the level of unemployment is already high. However, if a country in this situation does nothing about its balance of payments, some or all of these consequences may ensue naturally from the operation of market forces. In particular, falling exports and rising imports lower the national income (refer back to Chapter 7, pages 145-6, if you have forgotten why), thereby tending to restore equilibrium to the balance of payments.

(3) Exchange Rate Variations

The third solution is to use the exchange rate as an instrument to reduce the imbalance between international flows of payments and receipts. Devaluation is normally called for when there is an excess of demand over supply for foreign exchange.11 The mechanism by which exchange rates operate has already been explained. Its efficiency depends, as we saw, on the responsiveness of exports and imports to price changes. There is, however, one important consideration that has not yet been mentioned. In so far as devaluation increases the domestic prices of imported goods, it raises the level of home costs and prices, thereby reducing its effectiveness. Strict accompanying monetary and fiscal policies may be needed to inhibit such inflationary effects of devaluation.

The extent to which exchange rate variation can be used as a policy instrument depends on whether the rate of exchange is fixed or flexible, that is, allowed to vary with the forces of supply and demand in the market. During much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries exchange rates were fixed by the operation of what was called the gold standard. Under this system, countries maintained a stable price of gold in terms of their own currencies. This effectively fixed the rates of exchange between the currencies of all countries on the gold standard. More recently, since the early 1970s, most nations have adopted variable exchange rates, though governments nevertheless continue to exercise some influence on the rate of exchange by intervening in the market — buying and selling foreign currencies.

(4) Direct Intervention

The final set of policy instruments available to one country suffering pressure on its balance of payments involves direct interference with international transactions. Attempts to cut expenditure on imports, for example, can be affected by the imposition of tariffs (import duties) and quotas. Exchange controls can also be used to restrict the outflow of foreign currency for travel, investment, and so on. Taxes and subsidies can encourage exports and the production of substitutes for imports. Direct intervention of these kinds has two signal disadvantages. In the first place, it interferes with the international division of labour whereby countries specialise in the production of goods and services for which their particular endowments of factors of production best suit them. Students may recall the discussion of the principle of comparative advantage and the gains from specialisation and trade that it can create (see pages 27-9 above).

The second disadvantage of direct controls is that they may lead to retaliation. When a country restricts imports, this necessarily means a fall in exports for others, who may retaliate. Tariff wars can ensue. The resulting proliferation of 'beggar-my-neighbour' policies may be self-defeating all round and depress the volume of world trade.

We may close this discussion of international economic policy by emphasising the interdependence of nations. They are bound together as a result of international flows of payments and receipts for all purposes. Movements in incomes, prices and interest rates in one country have inevitable repercussions on others. If one country suffers balance-of-payments pressures and its exchange rate falls, at least one other country 'enjoys' a rise in its exchange rate which, it is important to add, may not always be viewed as an advantage, since it reduces the competitiveness of its exports in world markets.

Countries have, therefore, profound interest in each other's economic development and policies and in maintaining a high volume of world trade. A number of international organisations have been set up at various times to try and co-ordinate the aims and objectives of nations in the interests of all. The best known, on a broad front, are the International Monetary Fund and GATT (the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade), but international co-operation also takes place on a smaller scale, such as by members of the EEC in the Common Market.

The Choice of Policy Instruments

We turn back from balance-of-payments problems to consider the difficult question of how to choose between the three major sets of policy instruments: fiscal, monetary and prices and incomes policies. This is a highly controversial matter, as must be clear from the way attention has been drawn in this chapter to alternative views of the manner in which the economy functions. Different policy recommendations are, at least in part, attributable to varying beliefs about the causes of economic events and the sensitivity of economic behaviour to different stimuli as well as about the length of time that policy instruments take to work.

Monetarism Versus Keynesianism

As we have pointed out, economists are often grouped into two leading schools of thought on macroeconomic policy, Monetarist and Keynesian. So long as it is not forgotten that many individuals stand in intermediate positions, such a simple division may help in understanding the principal differences in the basic attitudes of the two schools.

They start from a common agreement that it is important to emphasise. The statistics of past history show an unquestionably high correlation between changes in the quantity of money and changes in the money value of national income, in many countries and at many times. A major point of difference between Monetarists and Keynesians, however, relates to the nature of the causal chain between money and income. For the former group the causal sequence goes from money to income, that is, changes in the quantity of money cause changes in income. Keynesians, in contrast, do not deny that this may sometimes occur, but they believe the causal chain is frequently the reverse, that is, that changes in income cause changes in the quantity of money. The statistics cannot prove conclusively that either side is correct.12

The importance of money to the policy prescriptions of the two schools arises from the fact that they have different views of the sensitivity of certain key categories of economic behaviour to changes in the quantity of money. They would move much closer to each other if it could be established that savings and investment were highly sensitive to changes in the rate of interest (Monetarism), or were mainly determined by other factors, such as income and the state of business confidence (Keynesianism).

Many of the controversies encountered in the last two chapters reflect these basic differences about how the economy works - for example, whether there is, or is not, a trade-off between unemployment and inflation in the short and in the long run; whether inflation is always due to an excess of aggregate demand or can arise from the cost side; when changes in aggregate demand lead to changes in output or in the price level; how much unemployment is purely structural and, therefore, incurable by increasing aggregate demand; whether expanding public expenditure raises incomes or merely 'crowds out' private investment expenditure; and so on.

One important aspect of the choice between policy instruments is how long they take to work. Two kinds of time-lag are involved: those delaying the implementation of policy and those delaying its effectiveness. The preference of Monetarists for monetary policy partly reflects doubts about the speed with which fiscal policy changes may be made. Although there are some built-in stabilisers in most tax systems, discretionary fiscal policies can take time for evidence to be collected, interpreted and acted upon by policy-makers. Moreover, given the delays in the production of some essential data, the policy needs of the moment may turn out to be quite different from those indicated by recent history. When it is recognised, too, that there are sometimes important errors in the data themselves, it is fair comment that the economic forecasting essential for proper policy decisions is far from perfect. Monetarists, therefore, tend to prefer reasonably straightforward non-discretionary rules relating to the rate of growth of the money supply, which should be designed to lead to price stability and the steady growth of output in line with long-run productivity trends. Keynesians, in contrast, are more concerned with the time-lags after policies have been put into effect. There seems little doubt, for example, that contraction of the money supply works a good deal more quickly on the level of output and employment than it does on the price level. The reluctance of Keynesians to rely on monetary policy as the sole instrument for the control of inflation reflects concern for the short run, when output falls well before the price level is brought down.

It must be added that there is a certain fundamental difference between Monetarists and Keynesians on the question of whether the economy contains sufficient self-correcting mechanisms. The former school believe that it does and, moreover, that there is little hope or point in trying to rush them, because any attempts in that direction often turn out to be ineffective or, worse, counter-productive. Keynesians, in contrast, do not deny that, given enough time, economies will solve many of their own problems. They could hardly argue otherwise. Every slump in history has eventually been followed by a boom. The Keynesian emphasis is, rather, on the short-term costs, both economic and social, of inaction. It seeks to avoid years of low-capacity output which has, arguably, been amenable at times to government intervention.

Finally, one is forced to admit the existence of different political and philosophical stances between schools of economists about the role of government and the priority that should be given to economic growth, price stability, full employment and the distribution of income. Economists are citizens and it is unrealistic to imagine that they are never influenced by personal political views. Monetarist policies tend to be attractive to political conservatives, who are less tolerant of government influence in the economy. Keynesian solutions, on the other hand, appeal more to those who are relatively optimistic about the effects of giving power to the state.

In conclusion, it must be said that it is virtually impossible tor any living person to be totally objective about these controversial matters. The author is alive and well and the reader is entitled to know his position in so far as it affects the presentation of the problems of macroeconomic policy. To end, therefore, with a personal view, I would submit that the differences between Keynesians and Monetarists are often exaggerated. Both schools recognise the key role of aggregate demand, but have different views on how and how much to try and regulate it. One suspects that policy disagreements would be greater in periods of inflation than in those of heavy depression. Hence, were there a repetition of the extremely low output, production and employment on the scale of the 1930s, many Monetarists and Keynesians would welcome both fiscal and monetary expansionist policies. In the inflationary conditions experienced since the 1970s, the contrast between the policy recommendations of the two schools is greater. However, both agree that inflationary expectations may play a key role in the inflationary process. This has led a number of economists of both persuasions to see some place for prices and incomes policies, at least occasionally and, in the short run, specifically in order to exert influence on such expectations. There is agreement, too, on the desirability of increasing mobility in the economy to counteract structural unemployment that accompanies technological advance. Extremist views will doubtless continue to be heard on both sides, but if we can improve our understanding of the way the economy works they are likely to move closer together. For the present, we have to live with the debate continuing.

Notes: Chapter 9

1 For a careful discussion of the problems of economic policy formation, see Hartley, K., Problems of Economic Policy (Allen & Unwin, 1977), chs 1-3

2 They are known by the clumsy title of 'expectations augmented Phillips curves'.

3 The argument of this section is based on the assumption that expectations axe based on past experience. It is not the only possible one. If businesses and workers correctly anticipate all future price changes, aggregate demand cannot increase employment even in the short run. All the economy can do is to move up (and down) LL' in Figure 9.3. This is the implication of adopting what have been called rational expectations, when the community is so well informed that it anticipates all relevant changes before they occur.

4 The ratio of liquid 'reserve assets' (as they are called) to total deposits could, in principle, be varied in accordance with policy needs. This technique is not used in the UK.

5 There is, however, doubt about the extent to which the Bank can control the real quantity of money (that is, the money supply adjusted for changes in the price level) unless it can also control inflationary expectations.

6 Public sector borrowing may be inflationary when it raises the liquidity of the banks. But the evidence is that by no means all of PSBR borrowing is of this kind.

7 Importers and exporters in R will demand and supply sterling; the former to purchase H's exports, the latter to convert the sterling proceeds of their sales to H into their own currency.

8 According to the Purchasing Power Parity theory of exchange rates, a given percentage change in relative domestic price levels is fully reflected in percentage changes in the rate of exchange between domestic and foreign currencies.

9 Elasticities of supply are also relevant, as readers of more advanced texts will find out.

10 Market forces can provide means of reducing the risks of suffering from exchange rate movements. 'Futures' markets exist where one can buy or sell foreign currency for delivery at a future date, but at a price stated at present.

11 If the elasticities (of demand and supply) are extremely low, revaluation upwards might be a remedy.

12 See below (pages 244-5) for an explanation of the difference between statistical correlations and causes.