2

LEVEL TWO—COST CONTROL

LEVEL TWO IS the second level of IP management evolution for firms involved with intellectual property. (See Exhibit 2.1.) Companies at Level Two are in defensive mode, just as they were at Level One. The difference is that Level Two companies have realized that IP is an expensive form of defense and they are looking for ways to manage the cost-benefit relationship so that they get greater results for their IP investment dollars. Indeed, companies at this level have come to realize that IP is an investment and it is one that requires management. Getting a real (or even a perceived) return on that investment requires that the costs be controlled as well as the outputs. For this reason, companies at Level Two find themselves interested in activities that reduce cost, increase efficiency, increase effectiveness, and raise productivity.

According to Joe Daniele, Senior Vice President of IP and Technology Commercialization at SAIC,

What you find is, if the work is well organized, there's actually less work to do and more output. It's a matter of efficiency—less in and more out. If you're going to be competitive, and you're spending millions of dollars a year to support your portfolio, you want to make sure that portfolio is doing something for you. It's not just sitting there gathering dust. It's there to allow for licensing, cross-licensing and trade, to protect your products, to allow proprietary positions, and to allow you to do partnerships and various equity-based arrangements as well. An IP portfolio can be a really valuable asset, and you want to make sure you're actively and efficiently managing that asset.

WHAT LEVEL TWO COMPANIES ARE TRYING TO ACCOMPLISH

Companies at Level Two look beyond the defensive focus of Level One firms, although both use similar elements in their IP management decision systems. At Level Two, companies are trying to accomplish two things:

- Reduce costs associated with their IP portfolios

- Refine and focus the IP that is allowed into their portfolios

At the same time, companies continue to be engaged in two creative processes, as they continue to generate patents, and to refine the processes used to manage patents and the patenting process.

At Level Two, patents in the portfolio and the patenting processes are by now in place. Management efforts in Level Two are directed at improving the patenting and patent management processes in order to minimize the costs and to maximize the defensive benefits from patents.

In the previous chapter, we did not mention cost control, and for a good reason. Companies operating primarily at the Defensive Level (Level One in our pyramid) often lack any formal cost-control measures. They merely review each patent individually when it comes up. As a result, they may be blind to costs in the aggregate.

By contrast, companies operating at the Cost Control Level, or Level Two, take a higher view. They see the pattern and can aggregate costs. They separate small-dollar from large-dollar decisions—dealing with the former routinely, while giving the latter an extra level of review.

The benefits of such scrutiny are obvious. By reducing costs, companies increase their profits. This is particularly true in the later years of the life cycle of patents, when costs become higher. For example, renewing a patent in Sweden can cost up to $1,000 per patent. This may not seem like a lot to a company with millions of dollars in patent revenue, but multiplying it by 500 yields half a million dollars—not an unusual amount for a very large company. In fact, Fortune 100 companies that have studied their patenting costs have learned that their patents cost them approximately $250,000 to $500,000 per patent worldwide to obtain and maintain it over its average two-decade lifespan.

In our consulting practices, it is not unusual to find that anywhere from 5 percent to 50 percent of a company's portfolio is no longer useful and could be eliminated. Thus, just by reviewing their portfolios, many firms could realize immediate savings of hundreds of thousands of dollars! This chapter will describe how and where companies should begin to cut costs.

Companies operating at the Cost Control Level are much more proactive about patents than are companies operating at the Defensive Level. For Level Two companies, it is important to understand what patents the company holds and what patents the company is currently in the process of obtaining. Technology applications have greatly enhanced this previously tedious process. For example, many companies offer special software that can automate docketing:

- Patent Management System (Computer Packages Inc.)

- Global IP Estimator (Computer Software Associates)

- Patent Management System (Dennemeyer)

- PC Master (Master Data Center)

The electronic IP inventory systems used by Level Two are more functional than simple reminder systems. They help companies better understand how to link their innovations to cash flow, by allowing easy access to information which allows the routine evaluation about whether the patent is worth maintaining or whether it should be permitted to lapse. Some companies have even gone so far as to create their own internal applications, as IBM has done, which we will discuss later in this chapter.

It is also easier to get information about what competitors are doing. Until November 2000, patents remained confidential during the filing phase, but were published at the time they were issued. The law changed at that time such that, except under certain circumstances, all patent applications are now published 18 months after filing. To find out what patents have been issued by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, one merely needs to look up the agency's web site: uspto.gov.

Furthermore, the following sites—some free, some fee-based—offer not only basic information about patents, but also various kinds of analysis as well (all beginning with www. in the address):

All of these analytical tools can help move a company from being a merely “defensive” firm operating at Level One, to a proactive firm operating at Level Two and beyond.

BEST PRACTICES FOR THE COST CONTROL LEVEL

These tools are valuable as far as they go, but Level Two companies go further. They adopt a series of best practices—often including these five. (See Exhibit 2.2.)

Best Practice 1: Relate Patent Portfolio to Business Use

Fundamental to the intent of companies at Level Two is the need to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of their patenting activities. In accomplishing this goal, companies must be able to match patents with the firm's business strategies and objectives. Any system or framework that increases the degree of alignment of the patent portfolio with business strategies will enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of the patent activity. Several best practices companies, all early participants in intellectual property management, have devised frameworks or schemes for categorizing current or prospective patents (and innovations) in ways that facilitate both tactical and strategic decisions about the patents in their portfolio.

To more effectively manage their intellectual property portfolios, companies must first know what their portfolios contain. This involves knowing not only simple portfolio demographics (e.g., numbers of patents and technologies, technology groupings, remaining patent life), but also information about the content or usability of the patents. Such information is useful for three reasons:

- To obtain a clear picture of corporate technology assets and their value to support further strategic decisions and transactions

- To be able to capitalize on technologies and their value as they become less valuable for internal use (usually due to changes in corporate strategy, etc.)

EXHIBIT 2.2 IP Cost Control: Best Practices

Best Practice 1: Relate patent portfolio to business use.

Best Practice 2: Establish an IP committee with cross-functional members.

Best Practice 3: Establish a process and criteria for screening patents.

Best Practice 4: Set detailed guidelines for patent filing and renewal.

Best Practice 5: Regularly and systematically review the portfolio to prune patents not worth maintaining.

- To have a capability for providing information to stakeholders (investors, customers, employees, etc.) on the state of development and use of company technology assets

There is no single right way to categorize. Some companies may make a conscious decision to keep only patents related to their core technology. Others may obtain patents that do not relate to their core technology, but that can protect against competition. Japanese firms are more likely to use this approach than are U.S. firms. One-third of Japanese firms reported holding 1,000 patents they do not use in their business, compared with 7 percent of U.S. firms.1 In firms like this, as few as 3 percent of patents may be used to support current business. Is this practice good or bad? The answer depends on the nature of the company's industry and the nature of the invention being patented. The important thing is to establish a classification scheme for the portfolio.

Companies categorize their intellectual property portfolios differently. Some companies classify the portfolio based on technology areas (IPC codes for example). Other companies classify their portfolio by business division. And yet others categorize their portfolio as “must have,” “nice to have,” and “junk”—not currently used by the company. When one company reviewed its patents vis-à-vis the above criteria, it found that only 20 percent were in the “must have” category,” 30 percent were “nice to have,” and 50 percent were “junk.” Today, by following the “best practices” described for Levels One and Two in this book, the company has a different profile. It has more than doubled its percentage of “must have patents” to 45 percent, and it maintains few if any “junk” patents.

IBM uses all of these approaches. It has developed a detailed framework of technology categories optimized to the IT business, which it calls patent portfolio management codes. Every patent is placed in one or more PPM codes, enabling IBM's portfolio managing attorneys to quickly access patents related to a given competitor's technology, to group patents for maintenance evaluation, and to understand overall portfolio strength across particular technologies. IBM's codes are continuously updated based on its research activities, ensuring a forward-looking applicability IPC codes are unable to match.

At the same time, IBM assigns and maintains one or more division codes for each patent, supporting correlation of the portfolio on a business unit basis. Finally, every patent is given a relative value score from 1 to 3, indicating overall value to the portfolio. This score is based on factors such as claim scope, applicability to a standard, past usefulness in licensing, association with Nobel Prize or other major award, coverage over an industry-wide practice, etc. Patent scores are regularly updated as patents issue and age. The scores are then used in making maintenance decisions.

All three categorization approaches are recorded in IBM's WPTS which supports full relational queries across categories. The categories thus integrate to generate value-revealing intelligence not obtainable from a single category in isolation.

One consideration should be the use of the patent. How does the company plan to use each patent? Will it be used to support an existing technology, to prevent a competitor from using a technology, or to reserve a technology for future use? All are valid goals, and should be spelled out as part of the company's criteria for assessing intellectual property.

Fortum (formerly Neste Oy) a Finnish company, is one of the largest energy companies in the Nordic region operating in oil and gas exploration and production, oil refining and marketing as well as in power and heat generation and electricity distribution. In 1994, Neste Oy was faced with the prospect of spinning off its petrochemical and polyolefin business and combining it with the Norwegian state-owned Statoil into a new company called Borealis. Neste, in anticipation of the merger, undertook a technology audit to help it better understand the contents of its existing portfolio, separate the petrochemical and polyolefin related technology assets to better understand the effect the Borealis merger would have on Neste's profitability and ability to extract more value from the company's existing intellectual assets. In Exhibit 2.3 Jan-Erik Osterholm, Technology Asset Manager for Fortum, tells the story.

A simple variant of the methodology developed at Fortum was utilized at Avery Dennison. “Our financial community had rank-ordered the 60 or so operating divisions into those that were in a growth mode, those whose operations we needed to sustain, and those that were cash cows that we either needed to milk or sell. We had also assigned our patents to each division the patent protected. Working with senior corporate and divisional staff, patents for each division were sub-categorized by use into those that were protecting products in current production, those in the division's strategic plan, and those outside the plan. It was quick and easy to make these determinations. Plotting the patents on a decision grid formed by the rank ordered divisions on one side and patent use on the other allowed our patent committee, division and corporate staff to quickly see which patents should be abandoned, maintained, licensed, or enhanced via continuing patent applications,” reports Paul Germeraad, former VP and Director, Corporate Research.

EXHIBIT 2.3 Relating the Portfolio to Business Use—Fortum

The purpose of the project was to optimize the value of Neste's technology assets by ensuring the ability to use technology assets (including intellectual property, IP) where it has the highest long-term return for Fortum, whether internally or through licensing, partnering, or spin-offs, and by minimizing the costs associated with acquiring, maintaining, and defending IP rights. To achieve such monumental change, the project was divided into several sub-projects, which included auditing technologies, establishing IP strategies and policies, creating a corporate IP organization and ownership structure, developing a trade secret identification and protection program, and establishing programs to educate employees and management about the IP and its expanded role within Neste and now within Fortum.

The original intent of the program was to audit the technology portfolio and determine its value based upon three different criteria: technology transfer potential, management purposes, and increasing shareholder value.

In the first phase of the audit, detailed information on all the technologies selected for the audit had to be collected. To simplify the process, we created a standardized questionnaire. We also created a Technology Classification Scheme for each technology.

As each technology (along with its associated patents) was examined, there were four main questions that needed to be answered:

- What stage of development was the technology in?

- What was its legal ownership status?

- What type of technology was it?

- What were its commercialization options?

In principle, we divided the technologies into either existing or preexisting. Existing, meaning the technologies are currently being utilized by the company; and preexisting, meaning they are currently under development. Regarding the ownership structure, they can be totally owned by the company, jointly owned by us and a third party or we could have licensed rights to use the technology. Next we looked at R&D, or development structure; had the technology been based wholly or in part on Fortum research, engineering, or development efforts, or entirely acquired through a license or other arrangement with someone outside Fortum.

Commercial exploitation status is the strategic importance of the technology to the Fortum portfolio. A key technology is a technology that provides competitive advantage to Fortum; it is not widely used in the industry or available to competitors. A “base technology” is used and readily available in the industry; it is necessary for Fortum, but not sufficient alone to provide competitive advantage. A “spare technology” is not currently in commercial use by Fortum.

A “pacing technology” is a technology under development that has not yet been exploited on an industrial scale, although it might have monetary value and could be exploited through technology transfer. An “emerging technology” is in an early stage of research or development that has not been and cannot be exploited internally or through technology transfer. Emerging technologies generally have not generated any patents or research results of monetary value so far.

After creating the classification scheme, we spent the next year interviewing the R&D staff to inventory and classify approximately 200 technologies within Fortum. The interviews were conducted jointly by members of the technology asset management function and by the R&D business unit management. The information was entered into an Access database and made available to corporate management.

Prior to the audit, many Fortum managers assumed that its businesses actively used the majority of their technologies for product research and development. They also believed many of the technologies were probably being underutilized and could be capitalized in cash flow by granting licenses to other companies and by selling or exchanging rights of use. The results showed something altogether different.

More than 50 percent of the patent portfolio was classified as excess! The excess patent portfolio has, during the years, been and is continuously actively exploited for profit. A substantial number of the excess technologies have been spun off into new companies as well as licensed. In addition we also had several other key learnings; some divisions and business units are already using the information generated by the new database as a planning tool for future activities. Some are rethinking their patenting and licensing policies. One of the first reactions to the audit was that the information was “dangerous” because it revealed that many patents could be categorized as excess and that a big portion of the rest were not the focus of future business. As a result, some businesses began to wonder whether filing patents was necessary at all, or whether they could build their business only on know-how and trade secrets.

We found out that many of our technologies were not transferable. Their primary value was in the know-how, expertise, and processes that are not necessarily patentable but that could be used when selling our engineering consultant services.

The Microsoft Access database created for the audit is an excellent tool that can be used effectively as a database for annual planning and budgeting for different businesses. Using the database, business units can create technology leverage in their portfolios by benchmarking what others are doing and determining what competitors are active in their business. To maintain its reliability, we update the database once a year.

Jan-Erik Osterholm, Fortum

Best Practice 2: Establish an IP Committee with Cross-Functional Members

The IP Committee is typically the body charged with the responsibility of deciding in which of the employees' innovations the company will invest. A decision to pursue a patent is also a decision to invest a substantial amount of money into an innovation. The committee should receive guidelines from the corporation as to what kinds of patents are desired for the portfolio, as well as what the corporation intends to use the patent portfolio to accomplish. With these inputs in mind, the IP Committee may be formed.

“Formation of an IP Committee involves several things,” said Patrick Sullivan, of ICMG. “First of all, it requires that the corporation decide what kinds of decisions or actions it wants the committee to make. With this in mind, one can determine the kind of membership (i.e., functions and organizations to be included as well as individuals) the committee must have. It can also determine how often the committee must meet in order to fulfill its mission for the corporation. Knowing the kinds of decisions that are desired (and the frequency with which these decisions must be made), the company can determine what kind of information the committee will require as input to their decision process. Information is either currently available through existing databanks, company information systems, or external information sources, or, it must be created. Information that must be created typically involves the creation of new work processes within the corporation to develop and provide information to the IP Committee.”

Barry Young, a partner in the Palo Alto-based law firm of Gray Cary Ware & Freidenrich, L.L.P., recommends that the patent committee be charged with two main duties:

- Develop clear screening criteria for determining what patents should be included in the portfolio.

- Review invention disclosures submitted by technology staff involved in R&D to determine those that meet the predefined screening criteria, and ensure breadth and depth of claims coverage.

One of the goals of the patent committee is to show the technical community that the company is proactively managing its IP. Many technical folks become discouraged if they do not see many patents filed or granted each year. Why should they waste their time if nothing ever comes of it? Active patent committees encourage engineers to submit their disclosure forms, and to provide full information in those forms. Such encouragement is important.In our experience, some engineers see disclosure forms as “paperwork.” They would rather be doing their primary work (i.e., scientific discovery and application).

Looking first at the committee's membership, it should typically include representatives from the business units, research and development, marketing, legal, and possibly finance. The committee should operate as a permanent “standing” management committee, reporting directly to the individual in charge of intellectual property management at the company. It should meet regularly. Members often hold senior management positions, and have the power to delegate tasks as they see fit.

The business representative should be able to evaluate how this patent relates to the current and future business strategy of the company or business division filing the patent. The technical representative should be able to evaluate the technical capability covered by the patent and relate it to the current or future research being conducted. The marketing representative should be able to evaluate how this patent differentiates any current or proposed product or feature from the competitors, or if it is going to help differentiate any product/market offering. The legal function representative needs to be able to evaluate the quality, scope, depth, and breadth of the legal coverage of the patent. Finally, the finance representative can provide a useful perspective on the financial implications of strategies.

Rockwell International Corporation has used committees for many years. Recently, it has changed the committees' focus from “invention committees” to “innovation committees.” Jim O'Shaughnessy explains.

What we've found in the past is that our old invention review committees would sit around and get people working real hard to make the right decisions. Each committee focused closely on its business sector in relation to its competitors. But if someone came up with an idea that was a little out of the box, it was rejected because it doesn't fit that business. The committee members would say, “Oh, well we don't do this.” It was a classic case of local optimization. It was a sound decision for that committee but a poor decision for the company at large.

Furthermore, the committee is adding more members, since it can use the Internet to communicate.

Our typical innovation review committee right now has four engineers, plus one patent attorney. In the future, we could have 30 or 40 engineers, a few people from sales and marketing, the company nurse if she has relevant expertise and 10 patent attorneys. After all, they don't have to be in the same place at the same time nor do they need to weigh in on every aspect of every decision. Now we can target the considerable expertise of the company on making the best holistic decisions that will impact our future.

There are many variations on this theme. John Raley, the former Global IP Manager for a Fortune 500 company describes a process he has seen implemented at several companies:

The decision of whether or not to file a patent is made by a committee—a group—in each business or technology unit. The committee is typically composed of a cross-section of experts: technical managers, inventors, marketing people, and lawyers. Overall, there is a common decision-making template that has been developed at the corporate level so that there is a basic consistency in the decision-making processes used in each group. However, each group can add to the template as appropriate for their unique business or technology considerations.

Typically present in the common decision-making template are a few basic questions that focus on and drive home the business relevancy of the invention being considered for patent application. In general, these few questions take the form of:

First: Do we really care if others use our invention? If they did, would it really have that much of an impact on our business?

Second: How likely would others be to use this invention? The likelihood may be low if the invention is incompatible with the processes or product designs of competitors.

Third: Would having a patent deter others from practicing the invention? How likely is this deterrent benefit? It is fair to assume that companies will respect the patent rights of others, however, as Ronald Reagan said, “Trust but verify.” A subset of this is the “policeability” aspect—that is, how would you detect infringement? If it's not policeable, then is it really worth the time and money to file a patent application?

Fourth: What is the plan for utilizing the invention? The point being that if the invention is going to be commercialized, patent applications need to incorporate considerations that would dissuade competitive reengineering or “invent around” so as to obtain the same benefits as the invention yet not infringe the patent.

Of these four questions, says Raley, “the first three are ‘extrospective’—only the fourth is introspective. For years, many companies have asked only the fourth question. A big change is the transformation in corporate mindset from patents being an introspective decision logic to an extrospective decision logic. Or put another way, having a patent really does not enable you to practice the invention, but having a patent can disable your competition from practicing the invention.”

Ford Global Technologies, Inc. (FGTI), according to Fradkin, uses a similar patent committee process at Ford Motor Company. A key determinant in whether a disclosure should proceed to a patent is its support of the business. Bill Coughlin, FGTI's new President & CEO (January 2001), wants to take this process one step further by requiring an economic impact statement as part of the disclosure and decision making by the patent committees.

Determining how often an IP committee should meet is often an issue to be addressed. For companies involved in industries with short product life cycles and rapid changes in the competitive marketplace, IP committees should probably meet frequently. For companies in industries that are slower moving, with product life cycles measured in years (or even decades), IP committees may comfortably meet only quarterly.

In addition to the frequency of meetings, another concern is the amount of calendar time the committee may require to reach a decision. The companies whose external environment are highly competitive and rapidly changing may need to develop decision systems that provide very rapid turnaround on inventions presented for their review. For example, in Xerox, all transfers of IP into or out of the company are handled by a largely “virtual” committee, the Corporate Office for Management of Intellectual Property (COMIP). (See Exhibit 2.4.)

For patent filing decisions, many companies have technology assessment panels (TAPs), which are subcommittees of the company's patent committee. These TAPs are composed of technical, business, and legal people. They are set up by technical/product specialty areas and meet as frequently as needed. Meetings are called quarterly, or more often when there are a minimum number of inventions proposed in a technical area, or when there is a particularly “hot” invention. The invention proposals can be made available electronically ahead of time to all committee members for review and electronic comment prior to the meeting.

IBM's selection process uses a committee approach augmented by its expert software system, the PVT (Patent Value Tool). Committees known as Invention Development Teams (IDTs) meet regularly enough to process inventions within days of first disclosure on IBM's WPTS system. Meetings are called automatically by WPTS, based on inventor demographics and technology. Each IDT includes an IP attorney, a business person, at least one technical expert, and at least one inventor from the subject invention disclosure. Including the inventors on the team fosters positive invention development rather than a beauty contest atmosphere. The mission of the team is not reject/accept, but to broaden, sharpen focus, develop the disclosed idea into a valuable patentable form. The IDT is aided in its work by the PVT, IBM's expert system that asks a series of structured questions about the invention: market size, market maturity, claim scope, avoidance, detectability, nature of problem, fit of solution to problem, standards applicability, prestige factor, etc. Using the answers input by the IDT, the PVT generates a numerical score for the invention. The score does not dictate the IDT decision, but assists the IDT in analytically isolating the advantages and disadvantages of the invention. It improves decision-making efficiency, ultimately linking back into WPTS to provide an early value measure for use in rating patent filings, and later tracking high-value patents.

EXHIBIT 2.4 A “Virtual” Intellectual Asset Management Committee at Xerox

In firms with large IA portfolios, the transfer of IA into or out of the firm often involves the transfer of very valuable corporate assets and is usually reserved for senior management decision rights either at the divisional or corporate levels. For firms with autonomous divisions, and with the IA portfolio broken up and in part associated and controlled by specific divisions, this decision-making is done at the owning division. However, in firms where IA is considered a corporate asset shared across divisions, decisions on transfer are made at senior management often at office-of-the-president levels. At Xerox, this decision-making has been done centrally by the corporate office management of intellectual property (COMIP) committee consisting of the three senior vice presidents of corporate research and technology (chairman), corporate strategy, and the chief general counsel. The committee is managed by the corporate manager of intellectual property (the IAM).

At Xerox, the decision process is based on two principles:

- All IA (and IP) are corporate assets and all decisions concerning their transfer are office-of-the-president-level decisions.

- Time is of the essence in this decision making.

The COMIP committee meets monthly and reviews all transfers of IA (at Xerox, this includes know-how) into or out of Xerox and to subsidiaries. A proposal for IP transfer must be sponsored at the division president level and submitted on a form. The form includes a description of the IP to be transferred, to whom, the business reason, the value of the IP, any issues or liabilities, and a summary of the terms and conditions of the arrangement.

After preliminary review and revision for clarification, the proposals are electronically distributed to a group of MIP champions reporting to all division presidents or their equivalent worldwide. These MIP champions are given ten days to review and comment on any of the cases up for review. If they have not commented within ten days, then by the rules of the process they have answered in the affirmative. A Lotus Notes database is used to provide these cases and background documents to the intellectual property managers and champions, and to collect their comments. After the ten-day review period is over, the comments are reviewed, and case briefs, including the background of the case, the proposal, issues, and the recommendation of the IAM, are drawn up. The committee meets monthly to review these briefs and make their decisions. The results are distributed electronically worldwide within hours of the close of the monthly meeting.

Joe Daniele, formerly of Xerox2

Best Practice 3: Establish a Process and Screening Criteria for Screening Patents

One of the most critical activities for Level Two companies is patent screening. As Joe Villella reminds us, “It's extremely important to review your portfolio regularly so that not only do you keep the good patents from becoming abandoned, but you identify ones that should be abandoned. No one has unlimited funds for patents so it's really critical to review the portfolio to separate the wheat from the chaff.”

Patent screening is a common activity for cost-conscious companies. Whereas companies at Level One are often devoid of processes and formal criteria, companies at Level Two have come to realize that there is value in some degree of formality and process. While no one likes excessive process or mindless bureaucratic procedures, it is also true that people don't like to waste effort or be forced to rebuild a go/no-go patent decision procedure every time a new patenting opportunity arises.

Successful “IP Best Practice” companies have learned that there are a number of key bits of information and process that can significantly improve both the efficiency and the effectiveness of their patenting decisions. Some companies are “innovation-poor”—that is, they do not spontaneously receive a sufficient number of innovations from their employees. Companies in this situation should be interested in creating processes and methods that encourage the creation of new innovations. Other companies are innovation-rich—that is, they receive more innovations from their employees than they can commercialize. These companies should be interested in creating screens and filters to identify the innovations of greatest interest to the firm. The point here is that not all best practices suit all companies at this level. Companies must diagnose their situation to determine which of the best practices cited in this chapter really relate to their circumstance.

The screening should begin as early as possible—not long after a company has accumulated a large stock of patents. We have discussed in Level One how a company can encourage innovation. At Level Two, this process continues, but with more prudence. ICMG's Patrick Sullivan cautions, “There are a number of pitfalls that are not obvious when companies first move toward creating incentives.”

A story from Xerox illustrates this point. When Xerox hired George Pake in 1969 to head up what was to become its world famous Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), Jack Goldman, head of research at Xerox, told Pake that he should get the best people he could find and allow them the freedom to be creative. “Bottoms-up research is the only sensible philosophy if one wants to get the very good people,”3 Goldman reportedly opined to Pake. Indeed, Pake was given a multimillion dollar research budget and a charge to create the information systems and technologies necessary to drive Xerox into the 1980s. Further, he was charged with putting together a research facility that would rival the legendary Bell Labs. Pake set about his task with gusto and hired the best and the brightest from universities. In the end, the researchers at PARC invented the first personal computer, as well as pop-down software menus and the ubiquitous computer mouse. Through a torturous process of evaluation and reevaluation, the executive management at Xerox, when presented with the opportunity of pursuing its commanding lead position in personal computing, decided not to invest. Why did Xerox opt out of pursuing its dominant entry position in personal computing? The after-the-fact consensus is that while the company understood and had experience with paper and toner products, it failed to understand the technology of personal computing or its market possibilities.

The lesson to be learned here from the Xerox story is two-fold. First, don't create an innovative process that produces new ideas you are incapable of leveraging; instead create a process that produces innovations that match your business strategy. Second, when your innovative process does produce ideas outside of your business capability, identify ways the corporation can benefit from them before moving on.

Many companies would like to be in the enviable position of having too many inventions to file on each year. IBM labs produced over 10,000 invention disclosures in 2000. Hewlett-Packard's Steve Fox says he receives thousands of disclosures from HP's R&D groups every year, but only files on half of them. Fox explains:

There's a cost control aspect to this. We included in our patent review template a call for information that would help us control our costs in filing patent applications. In fact the first usage of the template was to filter invention disclosures focusing on the strategically important things. We pushed back everything else.

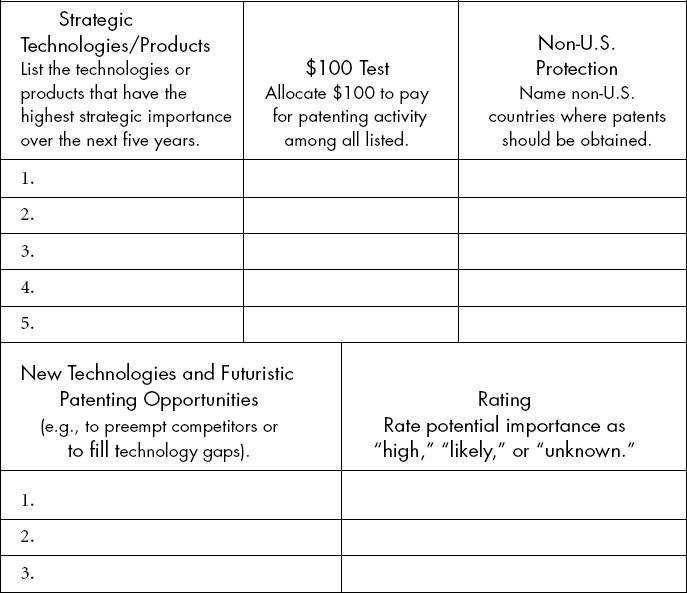

HP has historically created a fairly tight screening criteria for its patent portfolio: one part focuses on filing on inventions that could be commercialized within the next five years. For HP, time to market is a critical factor, as the technology life cycle is continually shrinking. The second part is more futuristically oriented. To help business unit managers prioritize their technology goals, Fox created a Patenting Survey Form (see Exhibit 2.5).

In subsequent years, HP started using that same template to determine not only which patents to eliminate, but also which type of patents to encourage.

Using the template more on a “pull” basis rather than as a “push-back” filter, we're getting a whole lot more invention disclosures than we used to. Inventions are strongly encouraged. When our new CEO, Carly Fiorina, came on board in July 1999, one of the first things she did was rebadge the company. She changed the logo, so underneath the HP logo where it used to say Hewlett-Packard Company, it now says “Invent.” This meant inventing and reinventing everything under the sun, whether it was marketing approaches, e-Services, customer support, or technology.

Best Practice 4: Set Detailed Guidelines for Patent Filing and Renewal

Even when an innovation meets the general criteria a company sets for its patents, it is not always necessary to patent the innovation in every major country, or to renew it continuously in those countries. Uncontrolled filing and renewal can lead to excessive costs. For many companies, filing and maintenance fees can soak up over 50 percent of a company's patent-related budget. It goes without saying that substantial savings can be achieved by knowing what these costs are and making deliberate decisions on where to file. These companies recognize, for instance, that the costs of filing and maintaining a patent in some countries outweigh the minor benefits to be obtained there. They are aware that patent protection means little in certain countries of the world. They also carefully consider those locales where they intend to employ the technology and avoid pursuing legal protection in areas of the world where they do not expect to operate.

Techniques include setting country filing guidelines, consolidating patent agents, and aggregating renewal decisions.

Setting Country Filing Guidelines. Companies that have progressed to Level Two consciously evaluate the countries in which to file each patent. Decisions and decision variables about country filings may differ in each case as they are affected by technology, by business unit, or by time frame. According to Bob Gruetzmacher, Director of Intellectual Property & Licensing at DuPont Intellectual Assets Business:

Many years ago, DuPont had established guidelines as to what countries should be considered (and not considered) when filing for foreign patent protection. A key factor of course is the business need. Beyond that, issues center around a given country's patent law and history of respecting others' patents, as well as a patentee's ability to enforce the patent in the country where patent protection is being sought. Over the last 10 years many countries have modified, if not overhauled, their patent system to be in sync with the majority of the developed world. As a result, our guidelines have been modified accordingly. However, the “golden rule” remains, file and maintain patent protection only in those countries where it makes economic sense to do so. When it comes to reducing patent costs, the foreign filings are the ones to receive early scrutiny.

John Raley describes in Exhibit 2.6 a process he has seen work successfully.

At IBM, both country filing and maintenance decisions are made on a globally integrated basis using IBM's WPT system, mentioned earlier.

EXHIBIT 2.6 A Successful Country Selection Filing Process

In obtaining a patent, the US may be “first to invent,” but the rest of the world is by and large “first to file.” Multinational companies need to consider both aspects. While it is important to be the “first to invent,” it is critical that patent applications are filed as quickly as possible in order to protect the “first to file” rights that the rest of the world operates under. However, filing in a large number of countries can prove to be prohibitively expensive. Fortunately, there are strategies that can lessen the cost burden while preserving patent protection options.

In filing a patent application, it is natural to be optimistic that the invention is going to be big and broadly valuable. But, as time goes by, it is often learned that the invention is not as big as originally envisioned or as broadly valuable. So the challenge is to preserve options for broad geographic patent protection while not going bankrupt doing so. Examining the fees associated with patent filings identifies opportunities to defer major filing spending, for a modest fee, while more is learned about the invention and its viability.

Initially, a patent application can be filed in the US.With the exception of a few countries (and these are getting fewer and fewer as time goes by), foreign patent filings and their associated costs can be deferred until one year after the initial US filing.

At that time, it becomes necessary to make the foreign patent filing decisions. A very cost-effective option can be to file a PCT (Patent Cooperation Treaty) application and elect all PCT countries as the filing option. For a modest PCT fee, this strategy defers making any filing decisions (and their associated costs) for PCT member countries for up to another 18 months. Companies can use this yet additional year and a half to learn more about the invention and its viability without losing their “place in line” in the PCT countries. For countries that are not PCT members, patent applications will have to be filed at this “one year point” but these countries are becoming fewer in number as more countries join the PCT ranks.

Eighteen months after the PCT filing, it becomes necessary to decide in which PCT countries to file patent applications. However, by this time, a company has had up to two and a half years after the initial US patent filing to learn more about the invention's business value. If the invention has proven to be significant, a large number of countries can be selected for patent applications. However, if the invention has proven to be not as grand as originally thought, filing can be in a smaller number of countries or not at all. Paying the modest PCT fee to reserve a “place in line” is much cheaper than initially paying patent filing fees in a large number of PCT countries.

Yet another opportunity at the 18 month PCT country selection point is to select the EPC (European Patent Convention) option. This further defers the need to file patent applications in EPC member countries (most European countries) for several additional years, sometimes as much as six years. Again, more time for the company to learn about the business value of an invention without needing to commit to the significant expense of filing patent applications in EPC member countries.

Deferring as long as possible the need to decide in which individual countries to file patent applications is good cash flow management as well as good R&D management as developers work to learn more about the invention.

Equally important is also having a good strategy for determining exactly which countries in which to file patent applications. At all of the above decision points, companies need to have a pragmatic decision template for selecting those countries in which to file patent applications. Without a good country selection strategy, companies risk having patents filed in too many countries (and paying for them) or not having patents filed in the right countries (spending less money but with questionable benefit). A good country selection strategy will guide obtaining patent protection where it matters most, thereby maximizing patent protection while minimizing the associated costs.

With many companies, the number of countries selected for patent filings varies by how valuable the patent is seen by the company. At first, natural optimism results in thinking that the invention is big, broad, and highly valuable. But as time goes by companies might learn that the invention is applicable only to a small set of countries—for example, developed countries only.

A good country selection decision-making template will integrate the business and technical assessment of the invention with an analysis of markets and competitors to determine the specific countries that are part of a filing strategy. Through time and experience the country selection list can be tailored to even further minimize patent application spending while not compromising protection of the company's intellectual property.

John Raley

With or without such advanced technology, it is a good idea to review all the countries where the company has filed patents to assess whether the patents are still appropriate. Criteria for this phase of the pruning may include location of manufacturing facilities, markets where products are sold, activities of competitors, local customs and attitudes regarding enforcement, and—last but not least—the cost of filing for patent renewal. Trademark filing guidelines are also worthy of consideration, according to Mark Radcliffe, senior partner of the Gray Cary law firm:

Every time I talk to people on trademark issues, I tell them to think about them in both defensive and offensive ways. On the defensive, you want to register not just in countries where you think you will have a big market for the product but also in countries where there are trademark pirates whose businesses are registering third-party trademarks and selling them back to the original owner. Additionally companies should think of registering in jurisdictions where you may not sell anything but where there is a high degree of piracy for your particular product. For example, in the clothing industry, Panama is a big transshipment place where pirates exist and so you may register there even though you don't anticipate having dramatic sales. In the computer industry, the People's Republic of China and Thailand are well known for piracy problems.

In some countries the patent protection is so weak or difficult to get effective enforcement that you rely on trademarks rather than patents as your primary form of protection. Trying to explain a semiconductor to somebody in Chinese can be very difficult. It is much easier to say here is the trademark and here is the thing they made and it is the same. The failure to do so can result in a real mess. If someone owns your trademark for clothing in Panama and they are manufacturing it, you have to chase them down all over the world instead of strangling it at its source, which would be in Panama.

When we advise on trademarks, we tell people to divide countries into three categories. Group One countries are countries where they will have significant sales in a year or year-and-a-half, or where there are significant piracy problems. You want to file in all these countries. Examples of this would be if you have a computer product you would register in the U.K., France, Germany, Japan, etc. but countries to register in to avoid piracy would be Taiwan, Thailand, and the People's Republic of China. Group Two countries would be smaller markets like Denmark or Finland. There is not a big risk of piracy there and their legal systems are pretty good. You may decide to save some money and put those registrations off. Other examples would be New Zealand and Australia. Group Three countries would be Liberia and Chad, where there is the risk of piracy and/or no chance of a market for your product.

Consolidating Patent Agents. While they focus on setting country guidelines, companies should also consider consolidating patent agents retained to translate, prosecute, and make maintenance payments on patents in other countries. Many companies have been shocked to learn that over time they have developed a network of hundreds of such agents throughout the world, all of whom operate independently, price their services at retail, and provide little accountability for the fees they are paid. One Fortune 50 company has achieved significant savings by consolidating those relationships from over 300 individual agents across Europe to one or two per country. By doing so, it has exercised increased buying power, negotiated more favorable fee schedules, and reduced the bookkeeping required to keep track of the hundreds of agents' bills received from around the world. Working with fewer agents in larger markets can help a company to obtain better fee schedules and to require less administrative time and oversight.

IBM's very large portfolio generates equally large maintenance fees. IBM uses selective pruning to control maintenance expenses and ensure that its portfolio is maximally tuned to the marketplace. IBM's pruning takes the form of intentionally permitting patents to lapse once their licensing value has diminished. IBM patent attorneys designated as Patent Portfolio Managers evaluate the licensing potential for each patent, and select those to be maintained. Thus, based on input from the portfolio size planning process, a given patent may be separately scheduled for maintenance in some countries but not in others, creating a “checker-board” coverage model designed to produce broad but not exhaustive coverage in every relevant technology in every relevant country.

Aggregating Renewal Decisions. Yet another way to save is to group patent decisions by size. No one wants to spend time making a “nickel and dime” decision. There are several ways to avoid doing so—and to concentrate instead on “big-ticket” items. One way is to put high-cost renewals on a separate track prompting an extra level of review. For example, cluster all European patent renewals (which are more likely to cost $250 apiece than the domestic cost of $20) for review by a single decision-maker. This could help in order to make the decision a $250,000 decision vs. a $20,000 decision.

Another way to aggregate renewal decisions is to put patents on a periodic, multi-year decision track instead of an annual track. John Raley describes how this process works.

Patents must be renewed in every country in which they are filed. Since filing dates and renewal periods can vary by country (see Exhibit 2.6), these renewal decisions do not come due all at the same time. Reviewing a patent for renewal each and every time the renewal trigger is pulled becomes a very tedious management task. Also, this becomes a country-by-country decision process and human tendency will be to renew the patent since it involves only one country and the renewal cost per patent per country is fairly small. However, while each renewal transaction is a small cost, the aggregate can be a huge expense.

Putting patents on a multi-year renewal decision cycle will result in much better management decisions. Re-casting the patent renewal decision as a dollar amount to keep the patent in force in all countries in which it is filed for the next several years will yield a much higher dollar amount associated with the decision. It is the nature of management that higher dollar amounts are subject to more scrutiny regarding the business value being obtained/retained for the money being spent. When the dollar amount is bigger, people put more effort into the decision, and a better decision is typically the result.

The decision can be made to unilaterally not renew the patent, renew the patent in only selected countries, or unilaterally renew the patent. If the patent is renewed, the odds are low that business circumstances will change sufficiently to reverse that decision before the next renewal decision cycle. If a patent is not renewed (or renewed in a small number of countries) considerable cost savings can be realized. This is particularly true for older patents since renewal fees typically increase significantly as the patent gets older. If a patent is filed in several countries, it is not at all unusual for the aggregate renewal costs over a patent's 20-year lifetime to exceed the aggregate filing costs for that patent. The cost savings realized by dropping patents that no longer serve a business interest is money that can be re-invested into R&D and help pay for broader filing of new patent applications relevant to business strategy.

In addition to improved cost management, a more subtle, and perhaps more important benefit of a multi-year renewal decision cycle is that it shifts the decision-making process from one of being country-specific to one of being focused on how the patent supports business strategy and plans.

Critical to successful implementation of a multi-year renewal decision cycle strategy is a good information system that documents the business and/or technology logic behind the renewal decision. In this way, when the patent is again reviewed at the next renewal decision cycle, the information from several years before is there and the decision is less vulnerable to the risk that the people who know about the invention may not be working for the company anymore.

Ford Global Technologies has a formal renewal process that involves both the FGTI licensing office and the firm's patent attorneys. The renewal team identifies technology bundles, checks on their status periodically, and makes decisions in the aggregate, not just on individual patents.

IBM has a noteworthy practice in this regard as well. IBM's approach, discussed earlier, first groups decisions by technology and business, to enable efficiencies on the basis of claim overlap and country characteristics. WPTS captures the “why” behind decisions and retains it along with all other information pertaining to docket quality, for use in subsequent reviews. To obtain size efficiency, IBM uses a maintenance model that concentrates review and pruning around renewal periods. This exploits two points inherent in patent systems and patents: many countries increase maintenance cost with time, and most patents outlive their usefulness with time, thus patents in the second half of their term receive close scrutiny, and pruning is more intense for them.

Best Practice 5: Regularly and Systematically Review the Portfolio to Prune Patents Not Worth Maintaining

Pruning is important for companies with large numbers of patents. Most large, established companies, with thousands of patents on file, have a lot of room for pruning. Many executives are surprised to learn that their patent portfolios continue to include patents on technologies as obsolete as the eight-track tape player. Other patents may be holdovers from R&D projects where the technology was later found to be commercially unworkable, too expensive, or no longer strategic to the firm. As discussed in Chapter 6, The Dow Chemical Company saved over $40 million in patent maintenance fees over a five-year period, by its judicious but significant pruning of the portfolio. According to Jerry Rosenthal, Vice President of Intellectual Property and Licensing at IBM, “We prune our portfolio every year.” Specifics of IBM's many pruning techniques have already been discussed.

Successful companies have found it helpful to set criteria for continual pruning. Many use the same criteria for pruning as they use for determining the characteristics of innovations they will patent. Dow, one of the leading best practices companies, created a decision process for its patenting process that required two different perspectives on the desirability of patenting. One perspective involved technical importance and interest, while the other involved business need and intended use. In deciding whether to patent an innovation, the participants in the process ranked each innovation on both technological and business dimensions. When culling the portfolio, Dow used both technological and business perspectives in arriving at its decision of which patents were to be culled.

On the other hand, IBM's pruning analysis differs from its filing analysis in that filing is heavily focused on future value, while pruning takes into account past and current demonstrated value.

Other best practices companies have created their own versions of criteria for patenting and pruning. One approach is to create a “value grid.” This is nothing more than a graphic representation of the company's patenting criteria. For many companies, the criteria may include not only technology and business considerations but also legal and patenting considerations as well. A simple value grid might contain three dimensions of value. The first is often the intended use for the patented technology, while the second is how enforceable the patent would be in a court of law, and the third is how prepared the company itself is to enforce the patent (i.e., sue over it). Companies can define different levels or degrees for each dimension and potential patents can be graded as to which level or degree they may be scored. When pruning a port-folio that contains patents graded by such a scheme, the pruning can be done, in part, based on each patent's score.

Sharon Oriel, Director of the Global Intellectual Asset and Capital Management Technology Center of The Dow Chemical Company, found that even getting management and the scientists to agree to the pruning process was difficult at first.

For many years, we had been rewarding inventors based on the number of patents they generated, and now suddenly we had classified those patents in the bucket called “no business interest.” For many inventors, they felt as if we had called their baby ugly. Additionally, some managers were very conservative and wanted to hold on to excess technologies, in case we might want to use it someday in the future. So we had a lot of education to go through and get people comfortable with this. I remember one day talking to a business manager, who had a technology he was not using but refused to get rid of, and I said, “How would you like to save three million dollars?” This was a relatively small business, so three million was significant. He looked at me and he said, “Is it legal?” And I said, “Yes.” And he said “OK, go do it.” Once I was able to monetize the savings, the decision was easy.

CONCLUSION

As Sharon Oriel's closing words reveal, cost control brings clear benefits to organizations—including the benefit of decision-making clarity. But the journey to the boardroom does not end here. Dow and other companies have progressed beyond this level. Companies cannot concentrate only on the defensive and cost control levels of our Value Hierarchy. If they do, they may miss opportunities to derive maximum value from their IP. To seize such opportunities, companies need to progress to the next level: the Profit Center Level.