3

LEVEL THREE—PROFIT CENTER

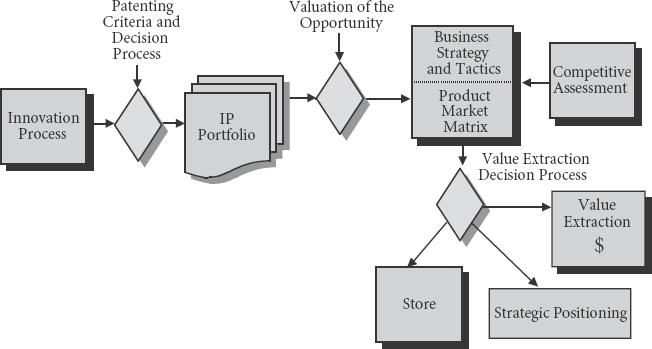

COMPANIES THAT HAVE moved to Level Three have crossed the Rubicon. They now realize that their IP generates value that transcends the revenue from their products and services. Whereas companies at Levels One and Two are focused on the defensive use of IP, companies at Level Three realize that they possess two kinds of intellectual assets. The first are the company's innovations themselves—the ideas that yielded the products and services that generate the company's prime revenue stream. But in addition, Level Three companies realize that the IP itself has value—notably in tactical (rather than strategic) positioning, and in the profitable generation of revenues (see Exhibit 3.1).

WHAT LEVEL THREE COMPANIES ARE TRYING TO ACCOMPLISH

Companies at Level Three see their IP as business assets, not just as legal documents. As business assets, the bits and pieces of a company's IP can become puzzle pieces in answering the great question: How can we succeed in building this company's value?

At this level, companies typically want to do two things:

- Extract value directly from their IP as quickly and inexpensively as possible

- Focus on noncore, nonstrategic IP that has tactical (as opposed to strategic) value

Companies newly involved with Level Three tend to look, quite naturally, for what is often called “low hanging fruit,” which are activities that will generate cash revenue quickly. For this reason they tend to focus on the IP that is already in the portfolio. They look for simple conversions of this IP into cash—typically through the mechanisms of licensing, donations, and royalty audits. Their view of the use of IP is most often tactical, leading them to create a capability for conducting simple assessments of their competitors and looking for marketplace opportunities within their immediate markets.

At Level Three, companies are concerned with more than the portions of the IP management decision system that are the province of the IP attorneys (see Exhibit 3.2).

The person in charge of IP management is now interested in converting into value the IP that is already in the portfolio. The focus of IP management activity shifts from what it was at Levels One and Two (IP as a legal asset) toward business activity that is concerned with the business use of the IP. At this level, IP managers examine the portfolio to identify its tactical use possibilities, as well as to identify what IP is marketable and what is not. We see companies creating the capability to value the individual pieces of IP as well as methods for linking it to the company's business and marketing strategies. Further, we see companies at Level Three concerned about their competitors' uses of IP as well as with how they might use their own IP to best tactical business advantage—all for maximum profitability in the short term.

Setting a profit expectation for IP can be a self-fulfilling prophecy. It increases the likelihood of profits—if only because of the attention being paid to the function. The attention paid to the IP function is likely to increase the level of care with which IP finances are managed, and the aggressiveness with which IP managers seek additional revenues. If such initiatives achieve their goals, they increase profits—by reducing costs, increasing revenues, or both, as feasible.

BEST PRACTICES FOR THE IP PROFIT CENTER LEVEL

Best practices for creating a successful IP profit center will vary from company to company. However, some practices remain constant. For example, in almost every case, managers will have to obtain “buy-in” from senior management. The actual operation of the profit center will vary, however, based on its location within the firm. When the IP management activity is located in the legal or IP departments at the outset of implementing Level Three, the initial revenue generation process usually takes the form of infringement-based licensing. The legal staff, trained as it is in enforcement and in litigation channels, typically establishes methods and procedures to identify infringers and then to require the company to demand a royalty payment from them in lieu of costly litigation.

For many Level Three companies (particularly those who retain their IPM under the heading of the legal or IP departments) this is as far as their Level Three activity goes. Other companies—those that see their IP as business assets—tend to take a broader view of the cash-generating alternatives available to them and begin to look at other revenue generation alternatives such as IP donations and royalty audits. They also begin to organize to extract value, and develop advanced screening criteria. (See Exhibit 3.3.)

EXHIBIT 3.3 IP Profit Center: Best Practices

Best Practice 1: Obtain management buy-in.

Best Practice 2: Start a proactive licensing organization.

Best Practice 3: Consider IP donations and royalty audits.

Best Practice 4: Organize to extract value.

Best Practice 5: Develop advanced screening criteria.

Best Practice 1: Obtain Management Buy-In

When companies approach us for help in extracting value from their intangibles, inevitably the first question they ask is, “How can I get management buy-in?” As is true for many of the mysteries of life, the answer is, “It depends!” In our many years of consulting, there are really only two ways to get management buy-in: You can appeal to greed or you can appeal to fear. There is not a CEO in the world who would pass up a sure chance to generate $1.5 billion a year in licensing revenue like IBM. The past 15 years has been a time where companies have been right-sized, downsized, reorganized, matrixed, realigned, and cost controlled to the point that the only unexploited assets left in the firm are its intangibles. CEOs are rapidly realizing that, to coin a phrase, “there is gold in them thar hills” and they are eager to have the newly found profits hit their bottom line.

As more and more companies tout their successes with intellectual asset management, it is becoming easier and easier for other companies to embark on programs to exploit their intellectual assets. Selling fear is much trickier, but more likely to result in immediate action. The road toward intellectual property failure is long and well worn by many Fortune 500 firms. Xerox PARC's inability to successfully commercialize many of the inventions that have revolutionized our lives in the past 20 years, most notably the personal computer, revealed an obvious deficit in intellectual property management. Apple Computer's unwillingness to license its operating system to software manufacturers cost the company the personal computer operating system standard. Other companies have spent many years and many millions of dollars on an R&D project only to watch it disappear as a competitor, only days earlier, filed patent applications that precluded their own project from ever reaching the marketplace. And yet others have found the costs of patent infringement so high that they are still paying to fund the patent owner many years after the fact.

Companies that have been at the wrong end of intellectual property management have the easiest time obtaining buy-in. According to Bill Frank, Chief Patent Counsel for SC Johnson,

In speaking with other IP Counsel, they have only been able to get their management's attention after something really bad has happened. We looked at our situation, and noted some anecdotal things that led us to believe that if we didn't make some changes, we faced increased potential of something bad happening to us. We were fortunate to get management agreement that this was important. However, even with that commitment, things take longer to accomplish than you might expect. From my experience, everything you think will take two months takes six. It takes time to build consensus and support. People may be willing to help but they also have many other projects and things to do all at the same time, which may have a higher priority than your project.

Regardless of whether you are using greed or fear as the motivator, the first thing to do is to find an ally or sponsor in upper management. Jane Tishman Robbins, former Director of Strategic Planning at Sprint Corporation, recounts her efforts at obtaining management buy-in. (See Exhibit 3.4.)

Best Practice 2: Start a Proactive Licensing Organization

One of the most important steps a Level Three company can take will be to initiate a proactive licensing program. A study sponsored by BTG, a global technology transfer company, estimates that companies ignore more than $115 billion in technology assets that could be licensed. The study, conducted independently by the British-based Business Planning & Research International, showed that “companies ignore more than 35 percent of their patented technologies because they don't fit into their ‘core’ business operations.”1 Ian Harvey, CEO of BTG, noted that for many companies, “selling or licensing their technologies could significantly bolster profits and maximize their return on R&D investment.”

EXHIBIT 3.4 Getting Buy-In at Sprint

I found that initially at Sprint, I had to get the support of senior management. To do so, I first had to make certain that we were all on the same page—that is, we were all speaking the same language (a common intellectual capital nomenclature) and understanding, or at least viewing, similar concepts in a similar way. Coming to this shared understanding of nomenclature and concepts was important given that the management audience represented a variety of functional areas within the company (technology planning, legal, tax, finance, business/corporate development, and strategic planning).

Very early on, we decided that we were going to focus our energy and effort on the area of intellectual property (a discrete subset of overall intellectual capital) for two reasons. First, intellectual property is the most tangible of the intangible assets, so our senior managers could “get their heads around it in short order.” Second, we already had in place systems and methods to both audit and inventory our intellectual property. So, we had a good sense of our current intellectual property assets; we knew what we were dealing with here. Thus, we quickly narrowed our intellectual capital management lens to focus on intellectual property.

Next, to give us perspective and a common analytical framework, I divided up the whole intellectual property management spectrum along three large component elements—IP value generation, IP protection and maintenance, and IP value extraction. Within each of these component elements, I identified current best practice work activities, decision-making processes, supporting systems and information, and organizational structures. Then, I used this IP value chain to do a deep-dive competitive analysis comparing Sprint and key competitors along this chain—examining available public information regarding the respective IP management organizations and activities while using the best practices criteria. Further, I employed the value chain to perform periodic updated competitive analyses to continue to apprise management of Sprint's IP management condition relative to that of our competitors.

Additionally, this IP management value chain was used for situation assessment purposes to size up our activities against current best practices, both within and outside the telecommunications industry. Here, I undertook a root cause analysis to better understand and explain Sprint's then-current IP management practices along the entire IP value chain, again from IP generation, to IP protection and maintenance, and finally to IP value extraction. So, the IP management value chain has been a helpful tool for us internally at Sprint.

We engaged in a comprehensive IP management competitive analysis and situation assessment (and sharing current best practices) but these efforts only went so far. To advance the ball, I had to make the case to management that Sprint had a business challenge that needed to be addressed. Thus, I had to convince them that there was an opportunity cost to maintaining the status quo, that we might be missing out on value—limiting our ability to extract maximum value from the IP portfolio in terms of cash, strategic position, enhanced supplier control, greater competitive protection, more design freedom, increased bargaining power, greater speed to market, etc. With these potential benefits of more active intellectual property management in mind, senior management had a much better sense of “what” the business challenge was and “why” it had to be addressed. Now, I just had to craft a “yes-able” proposal to address the lingering “how” questions—How much? How soon? How many people, support systems, and other resources will be needed? How do we organize and act to achieve our objectives? How do we fit this (if at all) within Sprint's current organizational structures and functional relationships?

Jane Tishman Robbins, formerly of Sprint

In the Profit Center mode, the culture of the company shifts to become more patent focused. Business unit heads and corporate executives are willing to consider the previously unthinkable—licensing patents previously thought to be most valuable if held exclusively. This process usually starts with baby steps—finding opportunities to generate revenues without forfeiting competitive advantage. The company begins licensing noncore technologies, or licensing outside the company's current field of services or products. All this is very different from the licensing activities of companies operating at Level Two or lower. Companies focused on cost control tend to have a “one-off” approach. They view any licensing income as a pure windfall rather than as part of a profit strategy. Understanding the specifics of its patent portfolio can help corporations know which patents are ripe for licensing, sale, abandonment, or enforcement.

Such a process can contribute a great deal to company value. Worldwide revenues from patent licensing have grown from $15 billion in 1990 to over $100 billion in 2000. Some experts estimate that companies are sitting on $1 trillion a year in unexploited licensing fees.

“I believe when properly done, IP licensing has the most compelling business model I have ever seen in my business experience,” said Dave Kline, Vice President of Technology & Licensing for Litton Systems. Licensing revenue can mean big dollars for companies. As we have mentioned earlier, IBM generates $1.5 billion a year from licensing income. Dow Chemical increased its licensing income from $25 million to over $125 million in less than five years. Some experts believe that a well-managed patent portfolio should generate licensing revenues equivalent to roughly one percent of the firm's total revenues and five percent of its profits.3 Licensing is a particularly cost-effective way to generate profits. Unlike patent-based revenues achieved through product sales, no additional volume in sales (and related expenses) is required to generate additional profits.

Before companies create a licensing organization, there are several things they should think about:

- What kind of technology is the firm willing to license?

- What type of licensing is the firm interested in?

- Into what markets is the firm interested in licensing?

- What kind of resource commitment is the firm willing to make?

- What level of revenue is the firm looking to generate?

From Levels One and Two, a company should have a fairly good idea of the existing intellectual assets it owns and is willing to license. Many companies we talk with who are interested in mining their patent portfolio for licensing opportunities are only interested in “naked patent” licensing. That is, patents with no associated know-how. This is often the case because CEOs do not want licensing to interfere with the core business of the company: selling products that have legally protected ideas in them. If companies are interested in revenue generation from licensing, they will not be happy with naked patent licensing only. It has been our experience that patent-only licenses are few and far between—and have relatively low revenue-generating potential. If companies are willing to add know-how into the licensing transaction, the amount of revenue generated will rise dramatically.

Licensing should not only be considered for patents. Trademark licensing is also a very lucrative business. Firms such as Coca-Cola and Sara Lee extract the bulk of their IP value (and even their corporate value) from their trademarks. Neither of them is a classic “manufacturer.” Instead, they license their brand to selected companies who make the actual Coca-Cola or Sara Lee products. Harley-Davidson has indicated that it receives over $300 million annually from trademark licensing. According to Jeff Weedman, Vice President of External Business Development and Corporate Licensing at Procter & Gamble, trademark licenses are about more than generating cash.

If I look at the amount of effort I put into a trademark license, it's comparable to what I put into a technology; yet the direct revenue stream is a lot less for the trademark licensing project. So why would we make such an investment? It's because when we license the Pampers name for baby clothes, for example, that's important for our baby-care business unit because it builds brand equity and ultimately total revenue. Consumers walking into retail aisles see the Pampers name not just on diapers and wipes, but also on a whole new line of baby merchandise. In effect, Pampers is fully meeting those consumers' need to care for their babies. Without a doubt, these types of licensing efforts support and strengthen the established brand. The company manufacturing the licensed products creates advertisements using the same Pampers graphics and visuals we use, so the impact on the consumer is much, much greater. It's a strategic play.

IBM's experience is similar to P&G's. IBM licenses its trademarks under carefully controlled programs to high-quality manufacturers of products complementary to IBM's own products, including printer paper, mouse pads, computer cabling, and laptop computer carrying cases, to name a few. The program generates significant revenues, and increases the visibility of IBM's major trademarks through the advertising conducted by IBM's licensees. By taking its program global, IBM has built brand loyalty in countries where it otherwise does not have a significant consumer presence.

Licensing transactions come in two varieties—carrot and stick—as explained by Bob Bramson, President of VAI Patent Management Corp., a technology brokerage and licensing firm:

There are two kinds of licensing of patents and technology in a broader sense. One is what we call “stick licensing,” which is about licensing patents against infringers who violate the patent by making products covered by one or more claims of the patent. Infringement-type stick licensing tends to be litigious, unfriendly, and aggressive, because nobody voluntarily takes out the checkbook and says how many millions of dollars do you want for your piece of paper (patent)? As I've often said, no chief patent counsel ever got a raise, a promotion, a bonus, or a pat on the back from the CEO for being the first one to sign up and write multimillion-dollar checks to somebody else who owns a patent.

You can also generate revenue (without litigation) by selling (rather than licensing) stick patents. This is common in the computer, electronics, and telecommunications industry, thanks to companies like Texas Instruments, IBM, Lucent, and Xerox. They have been aggressive in asserting their patents against infringers in that those companies are sought out by the TIs and Lucents and IBMs and Xeroxes to take royalty-bearing licenses under the licensor's patents. Often the alleged infringer will seek to expand its own patent portfolio to get more patents, which are infringed by the TIs and Lucents and IBMs of the world. And so, if you have a patent that is or may be infringed by any of these companies or other companies in the computer electronics/communications industry, you might find one of those potential licensee companies, or even a company in litigation that would be interested in purchasing the patent.

Carrot licensing is often called technology transfer. In carrot licensing, the principal licensed value is a new, better, or cheaper product. It's the technology that's being licensed. And the patent, although important, is of secondary significance. Nobody is going to take a license if they aren't convinced that you're giving them the ability to manufacture a newer, better, cheaper product. And then once you cross that hurdle, the issue of how well protected that newer, better, cheaper product is (by the patent) comes into play.

Whether you're doing stick licensing or carrot licensing, the process has three components. The first is the identification of a licensable opportunity, which may require the patent owner to sue people, or threaten to sue people, or to license the technology. The second element is the strategy of how you're going to realize value from the patents. And the third element is the implementation. Keep in mind that it's a lot easier to identify the dollar potential of a technology than to identify when licensing revenue is going to come in. And there are a lot of unrealistic expectations among patent-owning companies that are creating enormous pressures on the licensing executives' teams.

Companies new to licensing are usually interested in licensing noncore IP only, or else core IP into noncore markets. Using the Pampers story above as an example, infant clothing (noncore market) is not really related to the diaper market (core market). When deciding whether to license into core markets, Ford's Henry Fradkin relates four reasons why he thinks licensing into core markets is useful:

First, everything else being equal, our competitor pays more than Ford does because the competitor has to pay the royalty. Second, it is a lot better to have our competitor get hooked onto your technology than be refused and try to design around and perhaps come up with an even better design. Third, if our technical people know that the competitor is using the first generation or current generation of a particular technology or process usually that motivates the Ford engineers to go ahead and design the next generation so that we can create a new competitive advantage. Finally, selected technologies sometimes become industry standards. Isn't it a lot better to have the industry standard based on our technology rather than someone else's?

A secondary related advantage is that this can make our technology a “commodity,” resulting in lower prices Ford must pay to a supplier.

Many companies ask us, how do we get started? Our answer is, “Go back and talk to your technology people, they are probably being contacted daily by potential licensees.”

We have found that the best source of our deals come via referrals from our technical people, particularly when they are working with someone outside of Ford. It means that our engineers may be working with a supplier and the supplier is going to make parts or do a process for Ford Motor Company based on Ford intellectual property. The supplier and the engineer may realize, “This could be good technology to make parts or something for other companies, both inside and outside of the automotive industry.” But they realize that the supplier needs a license, and what will happen is that the engineer or the scientist or even the business person will call up one of us in the Technology Commercialization office, usually me, and say, “Such and such company would like to get a license to use our technology.” That's how it all starts. Every now and then we will get unsolicited requests from companies saying, “I saw your patent,” or “I saw a paper from SAE (Society of Automotive Engineers)” or “I heard about the technology that you have” and they are interested in licensing the technology. And probably the final way that we do get hold of people is we make cold calls. If we know that we have a certain technology and we read about something in the paper or we may do a citation analysis, we'll make a cold call on a company and say, “Have we got the technology for you!”

It is one thing to identify a few opportunistic licenses, and another entirely to create a licensing business. Most companies we speak with are interested in some kind of portfolio mining exercise. Portfolio mining is the systematic review of an intellectual property (usually patent) portfolio to determine opportunities for carrot and/or stick revenue generation. Most IP consulting firms offer portfolio mining services, and not all use the same methodologies. How is a company to know which is the correct methodology? On pages 78–80 (in Exhibit 3.5) is the experience of Litton's Dave Kline.

For a more detailed discussion of portfolio mining and how it is performed, please see Appendix A.

IBM is considered a leader in the generation of licensing revenue, and many companies want to emulate Big Blue. But many executives do not realize the resource commitment that IBM has made in order to generate over a billion dollars annually from licensing as described in Exhibit 3.6. For companies that want to duplicate IBM's commercial success from licensing, we ask, “Are you willing to hire large numbers of attorneys to place near your technology to capture all new ideas in order to patent them? Are you willing to license all technologies in your portfolio, regardless of whether they are core or noncore? Are you willing to license your competitors and force your technical folks to continuously innovate?” The answer of course is almost universally, “No.”

Clearly, the licensing activities of a Level Three company are quite strategic. Gone are the ad hoc characteristics of the Level Two company. In their place is a formal, written licensing policy and standardized license agreements. No patent is off-limits, regardless of how precious it may seem to its owner. Every patent has a price. Granted, that price may be quite high, but if a licensee is willing to pay, the Level Three patent owner is willing to license, even to a competitor. The Level Three company no longer waits for potential licensees to come knocking. Instead it has put in place a team to go in search of the right licensee candidates.

Best Practice 3: Consider IP Donations and Royalty Audits

Once management has authorized value extraction initiatives within the firm, the IPM team must find a quick success to help build momentum. Two of the easiest ways to do so are either an IP donation or an IP royalty audit. From Level 2, companies create a relationship between intellectual property and business use. The companies place nonstrategic assets in the “excess category.” Some of these excess assets will have no continuing value, so the company will stop paying maintenance fees and allow the patent to lapse. Some of them may still have value, but just not to the originating firm. Joe Daniele, Senior Vice President of IP and Technology Commercialization at SAIC, explains:

EXHIBIT 3.5 How Do Companies Create a Licensing Organization?

About a year and a half ago at Litton Industries we undertook a baseline benchmarking effort to try to understand what was actually going on in the commercial licensing area with some of our contemporaries and in some of the other industries that had undertaken it as a formal business endeavor. Our objective was to see what had been accomplished, who was in the business and what their business models were, as well as what tools and processes were available for this kind of activity. Our objective was to adopt “best business practices” in developing a business plan which would give us the maximum opportunity to leverage off the technologies that we have across all Litton divisions. This consists of four very technologically diverse businesses: Information Technology, Ships and Associated Systems and Services, Advanced Aerospace Systems and Electronics Components and Materials.

The benchmarking effort carved out a representative subset of the total corporate patent portfolio, of approximately 1,000 domestic patents. Contracts were placed with several different organizations each of which had a different approach to front-end patent mining and marketing. The activities fell into three categories: technology profiling/assessment, mining/valuation and pure marketing.

At one end of the spectrum is an approach that is highly technology oriented. It involves performing in-depth technical assessment of the various patented technologies and how they might relate to use by others. This included assessing fields of use and the problems and solutions they map into. The output includes identification of the industries and key companies involved in this technology space. This last element was added by Litton to assist in identifying potential licensing sources.

The second approach involved more conventional patent mining activity. The portfolio is structured into clusters of technologies which can be one or many patents. The clusters are assessed using automated patent search and other automated tools to establish current patenting organizations and potentially interested industries. This results in the ability to assess potential licensing interest in a particular technical commodity consisting of either individual patents or clusters of technology. For this approach we employed two different teams each employing its unique set of tools and processes.

The third approach involved heavy-duty marketing, which revolved around documenting and representing the technologies to communicate their benefits to others and getting it to a very broad group of potential users. This involved a great deal more follow up with many potentially interested parties.

The total benchmarking effort was carried out over a six-month period with the same subset of patents given to each organization. The patents selected were about 5 percent of the total portfolio representing a broad cross section of the types of technologies that we have across our businesses.

In parallel with this look at our patents, we attempted to understand the experiences of others. We found that a number of companies got heavily and aggressively into licensing activity only to find, after engaging potential licensing candidates, that there were internal issues and barriers within the business units which prevented moving quickly and continuously toward closing deals. This basically killed the whole process.

At Litton we have attempted to address some of these issues by combining the Chief Technology Officer role and patent licensing responsibilities under one organization. Working with all the divisions on technology planning as well as licensing, helps to eliminate unforeseen conflict between our business and licensing objectives. As indicated earlier, we have found that there are technologies that have been developed for a specific project years ago that were never fully exploited because they were not within the core business or long-term interest of a particular business unit—yet they represent a potentially valuable business asset to others. We were able to find a number of commodities that were not being exploited, which had been sitting dormant for some time. We found others that were being used by business units focused on their fixed customer market and were not being exploited in other concurrent non-Litton businesses.

We have some world-class information technology that is a number of years old but appears to be leading edge even against today's state of the art for knowledge-based search and network control. We have leading-edge technology in applying optics to the medical field that hasn't been exploited. We have some very interesting technologies used within our infrastructure for manufacturing processes and electronic/optical packaging that have uses outside of our normal business structure. We have some unique product-packaging technology that helps to protect and minimize the cost of items shipped. What we have found is technology that ranges from enabling new and innovative products, to improving the distribution and processing of information, to improved packaging and shipping of goods. It covers areas never contemplated or recognized for potential value beyond our own businesses.

Permit an observation and comment on the intellectual capital management (ICM) process. It was presented to us as a tool to be incorporated at the outset of our activity along with patent mining. I believe it is an important tool downstream for the realization of the fullest value and then ultimately the highest leveraging potential for your technology. However, it overwhelms the complexity of getting on with the basic business. I believe it is something that should be folded into the business process after you get a licensing operation rolling. In the long run, application of ICM will create much greater awareness of the potential value and applications of unexploited technologies. As a final note, it is clear that our early efforts and our implementation processes are likely to produce applications, interactions and relationships with new industries. It will very likely introduce our business units to new customers and lead them into new markets. It will help identify unused technologies that have commercial market value in other industries. It will also lead to the strengthening of our overall IP process, so that in the future we can expect to see growth in the quantity and commercial value of patents being generated. It will result in a much stronger management of the overall IP process across the Company. These are all very positive returns. Litton has had very positive licensing experiences to date.

David Kline, Litton Industries

EXHIBIT 3.6 The History of Licensing at IBM

We have been filing patents for about 100 years, literally since the company was founded. For most of our history we did not have a specific policy regarding cross-licensing. A major change in our approach came in 1956, when we were involved in antitrust litigation with the U.S. government. We agreed to license all our patents to any and all comers who respected our intellectual property. The last of the patents under the consent decree expired in 1991. Nevertheless, because cross-licensing has served us well, we have maintained our open licensing policy to this day.

Why do we cross-license? Speed. One of the reasons this industry moves so quickly—compared to almost any industry—is that companies in this industry cross-license their intellectual property to each other. Certainly for a fee to some, depending on who has more value, but the willingness to cross-license enables everyone in the business to continue to leapfrog technology. We started that way back in the '50s and it has helped get our industry on a path where competitors recognize value in licensing intellectual property.

Moving forward in time, the growth of the PC clone business in the mid-'80s caused us to ask: “What do we want to do now?” We invented the PC but other huge players grew the business around us. We had a choice to make at that time: Did we want to practice our monopoly and exclude others from the business? Or, did we want to license them and allow them to continue, to enable the industry to grow? We decided to allow licensing for the rest of the industry for what we considered very reasonable terms. At that time, the Dells and Compaqs weren't doing any R&D they were living off our R&D. We agreed to license them for royalties, all of which went back to the operating divisions to further R&D in those divisions. We were able to lower our costs of doing business and further our R&D. We made that decision in 1987. By the 1988–89 timeframe, it was beginning to become a significant income opportunity for IBM.

At that time, we were mostly interested in growing the portfolio and didn't worry about maintenance. There wasn't a lot of cost pressure at that time. We were getting about 700 patents a year, and for practically everything we filed in the United States and in the big five countries outside the U.S.

We probably have close to 1,000 licensees who are licensed to our patents either through royalty-bearing or cross-licensing agreements coming out of that phase of our development. We believed then and believe now it is an important way to keep progressing the information technology industry ahead.

In the mid-'90s, we moved into the next phase. We realized there was a new opportunity in licensing our technology and know-how in addition to patents. Given enough time, someone else would eventually duplicate our technology anyway. Therefore, they were going to catch up to us or get value from our technology one way or another. Why not license it out and enable others to avoid having to go through the expense of re-developing what we had already developed, at the same time open up a whole new revenue stream for IBM? We made that change in the 1995 time frame. In the years since then, technology licensing has become the biggest piece of our licensing business.

Once you license your technology, the only way you are going to win in the marketplace is move ahead and develop more new technology. Someone else now has the technology that was new yesterday.

To determine the value of our technology in a licensing opportunity, we look at what it cost us to develop the technology, as a proxy for what it would cost someone else to develop it. Then we ask how long would it take them to develop it. If it would take them three years as opposed to us making it available to them immediately, a time-to-market factor is added to the technology value. We go through a very rigorous methodology to figure out the value of it to the other party. We spend a lot of time doing that and we do it very closely with the division that developed the technology. They are the ones that have those answers.

Intellectual property licensing is not an operation we run from corporate in a vacuum. There is an extremely cooperative relationship between us and the operating divisions. We don't license know-how to a huge number of players. We look for players that will make a significant commitment to shorten the time we need to spend transferring the technology to them. We look for players that will be our partners, complementing our business. They may become a second source for others by using our technology. We help to create and maintain the standard of what we developed. We do not treat technology transfer merely as a way to unload intellectual property. For us it interlocks with and furthers other goals of IBM at the same time.

Jerry Rosenthal, IBM

SAIC is in its thirtieth year of existence and has never had a nonprofitable year. In a company that is consistently profitable, a process of regular, annual charitable donations of IP can be valuable. We have found that you can free up large amounts of cash in a short time with donations. In starting up an IP group at SAIC, one of the first things we did was an IP inventory (by an IP Task Force) to sort and evaluate the patents in our portfolio. We confirmed the existence of about 50 unused and non-strategic patents. Also, in most cases, the inventors had long since left the company, and so these were mostly naked patents, and they no longer had a strategic position in the portfolio. For the most part, they were representative of earlier times, projects and products that were no longer a part of the business. We could sell, license or donate them. We chose to set up a regular program of donation, so we were able to get the money upfront, via a tax deduction. This was a way to take unused assets that were no longer strategic to our operations, and turn them into free cash.

This approach gets attention. It helps pay the bills and shows how a sophisticated approach to intellectual property can turn unused, but valuable assets into cash in a way that may not have been expected. In addition, the donations bring a societal benefit, in that the IP is now used to generate income and new jobs.

IP Donations. It was The Dow Chemical Company that created the concept of donating intellectual property for a tax write-off. Dow managers reasoned that if you could get tax relief from donating a tangible asset, why not apply the same logic to an intangible? Sam Khoury, Dow's former Senior Intangible Asset Appraiser, headed up the IP donation concept within Dow, and by 1996, Dow had successfully donated its first intangible to a university.

There are several things to remember before embarking on an IP donation:

- Currently IP donations are only allowed as tax deductions in the United States.

- The donation value is the fair market value (FMV) of the technology.

- The FMVcalculation must be conducted by an independent third party.

- The recipient, must be a registered nonprofit 501(c)(3) entity.

- The donor and recipient must agree on the FMV of the technology.

- Once completed, the FMV calculation has a limited life, so the transaction must be completed within six months of the valuation.

As part of its work with the IRS, Dow needed to show that donating IP was not an activity that was specific to Dow; other companies could do it as well. Not surprisingly other chemical companies were quick to pick up on the idea, as Bob Gruetzmacher of DuPont explains:

Sam Khoury and I were having lunch back in the early nineties at one of the annual meetings of the Licensing Executives Society (LES). This was shortly after Dow completed its first donation. I was intrigued by what he had done and invited him to come to DuPont to describe the process to our Corporate Technology Transfer staff plus a few of our tax and finance people. Sam did pay us a visit and our audience really took a liking to the idea. Our tax and finance people wanted to spend time making sure that we established a consistent process (choice of donation candidates, valuation, etc.) which was in perfect compliance with the IRS guidelines. It took a little time given the size of our company and diversity of portfolios but eventually everything came together and we completed our first IP donation in late 1998. In this instance the technology gift was a textbook candidate for the ideal donation. It had recognized value and commercial viability, it was non-strategic to DuPont and had no ready buyers. Licensing was considered but DuPont no longer had the sufficient technical resources to effectively carry out the necessary know-how transfer to multiple licensees. In February 1999 we donated 23 more patents of significant value to three other universities.

Below are several more recent examples of donations:

- From December 1998 to September 1999, Ford Motor Company donated “bundles of technology” worth $40 million.

- In October 1999, the Procter & Gamble Company gave 40 patents to the Milwaukee School of Engineering. The value of the gift was not publicly disclosed, but the university called it the largest gift it had ever received, which means it was worth over $10 million.

- In January 2000, Eastman Chemical Company gave Clemson University a portfolio of U.S. and foreign patents worth $38 million.

- In January 2000, SAIC gave Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute hardware, software and a patent, valued at approximately $2 million, for a system for chemical analysis of the deep sea ocean bottom.

Companies donate IP for a number of reasons. Obviously there is a tax benefit. But surprisingly, most companies admit that they receive far more value in goodwill from universities and nonprofits than they do from a tax break. Jeff Weedman, of Procter & Gamble, explains:

The reason we donate technology is because we simply have too much of it to commercialize ourselves. Our donation candidates are technologies that have expensive technical challenges to solve before they can be effectively commercialized. It is a candidate for donation because we don't have the resources, capability, or desire to solve and develop it fully, particularly in light of the focus areas we've chosen to invest in and fully develop. However, the technology is regarded to be very robust, valuable, and potentially useful to many people. So, as part of our process, we donate that technology to a university, research, or not-for-profit institution we think is best equipped to solve those remaining technical challenges and successfully commercialize it. With the donation, recipients get full rights to the technology and they own it free and clear. If they can successfully solve the technical challenges, we'd even love to become a customer of the technology in some cases. Bottom line: A recipient can sell it or license it back to us—whatever they see fit to do.

Donating creates value from a technology which otherwise may not reach the marketplace in a useable form. Also, the donation forms a unique, interactive bond between the business and academic community. That's great for both of us. It's also good for the economy if the technology can be successfully commercialized; it will create jobs, build new companies, and, overall, improve the lives of consumers. Quite often, this is a situation that the universities could not have implemented or even dreamed of on their own. Clearly, our technology donation program is a winning proposition for all parties involved.

Royalty Audits. Level Three companies track their fees from licensing, typically paid as a stream of royalty payments. This activity does not typically occur at Level One and Level Two firms. Licensing occurs there, but it is often haphazard and very opportunistic. Many companies license when it is easy, for example when a potential licensee approaches them with an interest in a particular technology. While it is true that technology licensing creates royalty income, agreements need to be audited to ensure that the full amount owed to the licensor is paid. Profit-minded companies operating at Level Three, unlike purely defensive or purely cost-conscious companies operating at lower levels, realize that they may not always “reap what they sow” when it comes to royalties from licensing agreements. The most astute companies conduct what might be called a royalty audit—a review of license records to determine whether royalty payments have been correct. This is generally a matter of paying too little, too late. Some licensees even hold the royalty payments in an accrual account until the licensor asks to be paid.

The typical royalty audit includes documenting the licensee's compliance with the license terms. One component of this is a periodic monitoring of the licensee's business activities through publicly available information. A more powerful component, though, is the ability to conduct formal royalty audits of licensees. Most standardized licensing arrangements permit the licensor to send an independent auditor to inspect the books of the licensee. Additionally, the licensee is often required to pay the cost of the royalty audit if there is a discrepancy in royalty payments above 10 or 15 percent. Studies have shown that such audits surface an average underreporting of 12 percent, but the range is wide. While some companies find very little underreporting, others find it to be far greater. In our consulting work we have found underpayments as high as 50 percent.

Stanford University has a royalty audit program, as do Dolby Laboratories and Ford Global Technologies. In 1997, when Ford instituted its program, it found many cases of royalty nonpayment. One such case stands out for FGTI's Henry Fradkin:

One of my licensing managers called up a licensee and said, do you realize you haven't paid us royalties in 10 years and there is an annual minimum? The fellow was absolutely shocked. He went back to his license agreement and found that it was true. It turns out that his managers thought the license agreement had expired, since they were not using the technology and never received any notices. He offered to settle for ten cents on the dollar. When my manager responded, “You mean you willfully are saying you don't want to pay the royalties you owe us?” he decided to pay 100 percent.

In that case, the licensor was not using the technology, Fradkin emphasizes. In other cases, the licensee is in fact using the technology, in which case Ford may ask not only for back payment, but also may consider suing for infringement. Settlement payments in these cases can be quite significant.

Such discrepancies usually do not reflect a lack of integrity on the part of the licensee. Our experience suggests that the underreporting may be the result of changes in the licensee's product codes or model numbers or personnel. For example, as model numbers change, the person responsible for preparing the licensee's royalty reports may not be aware of new products that embody the licensed technology. When the old model numbers are phased out, the royalty checks dwindle to nothing.

Some licensors may be concerned about the effect that a planned royalty audit will have on the company's relationship with its licensees. Licensees, though, have come to expect royalty audits as normal business practice. You can be sure that their other licensors are also conducting royalty audits and that the licensees have grown accustomed to the practice. Auditing licensees is simply good business. After all, what other aspect of today's business world is conducted on the honor system?

As Jerry Rosenthal, Vice President of Intellectual Property and Licensing at IBM, the company with the most fully licensed IP portfolio, explains:

We have a pretty good handle on where most of our licensees are. We are in a lot of businesses. The money goes back to the divisions from which they came. The businesses know if the amount of royalties are vastly different than the published size of that business, we will write a letter to the licensee stating that we think we have a discrepancy here between what they published and the amount of their checks. We think they ought to take a second look at it. The problem gets fixed right then and there, 99 percent of the time.

At a minimum, royalty audits help clear up misunderstandings and discrepancies between the two parties about the meaning or interpretation of vague terms or conditions. We've even learned that licensees can find it beneficial to conduct a royalty audit as well. Such was the case when two large pharmaceutical companies had a dispute about the amount owed on a patent license. A royalty audit conducted by the licensee highlighted a $300 million difference between what the licensor claimed was owed and what the licensee's own royalty audit revealed. An arbitrator later selected the lower amount.

Having made the decision to engage in all these value-extracting activities, what form should that take? This now leads us to our next best practice.

Best Practice 4: Organize to Extract Value

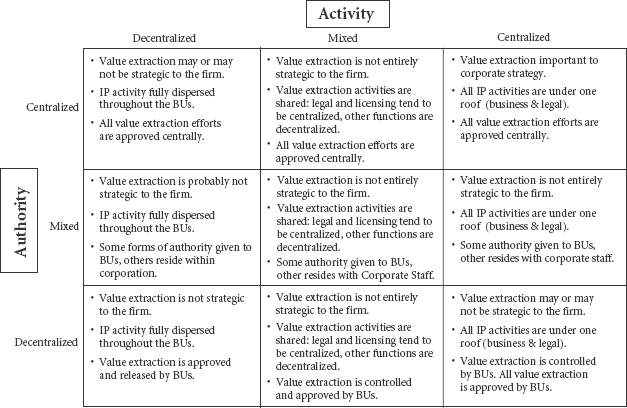

At Level Three, intellectual property management is now an activity that is larger than just the legal group. The activities that support IPM cut across a variety of functions: legal, R&D, marketing, finance, and strategic planning. How do companies decide what decisions are made at the business unit level and which ones are made at the corporate level? What activities are conducted at the business unit level and at the corporate level? And finally, does the revenue that is generated flow back to the corporation or business unit? These are all valid questions. To help us sort through these issues, we created an Authority and Activity Matrix which you can see in Exhibit 3.7.

The matrix results from a series of questions and answers that the people in a company's IP organization must pursue. Initial elements in this series are questions about what is the company's long-term vision, and where is it going. The answers to these questions trigger the next question in the series: What is the company's strategy for achieving this vision? Following the answer to this question, one must ask: What role(s) could intellectual property play in helping the company enable its strategy? The roles, once known, allow the company to determine which functions (see Exhibit 3.2) must be performed. Once the functions to be performed are known, the company can then ask itself how it wishes to organize in order to perform these functions.

In creating an organization, one of the frequently asked set of questions concerns the degree to which companies should centralize IP activities or decentralize them. Centrists argue that only by bringing IP management activities under one roof can one expect to control and direct the most effective uses of IP. Decentralizationists, by way of contrast, argue that the innovations at issue, along with their corresponding pieces of IP, were created by and for the business divisions and are rightfully “owned” and used by the business divisions. For this reason, the business divisions ought to be the home of any activity that manages and focuses the uses to which IP will be placed.

In our experience, there are two areas of consideration when companies debate the question of centralization vs. decentralization. The first concerns the authority to release any IP documents or matters outside of the company; the second concerns the activities associated with the IP management functions themselves. The following list includes these generally agreed-upon functions in business units (BUs):

- IP generation, protection, maintenance, and enforcement

- Portfolio inventory, management, and administration

- Portfolio mining and opportunity identification

- IP training, education, and process design

- Brand management

- IP transactions

- Competitive assessment

- Innovation

- Relationship management (customers, suppliers, others)

- Marketing

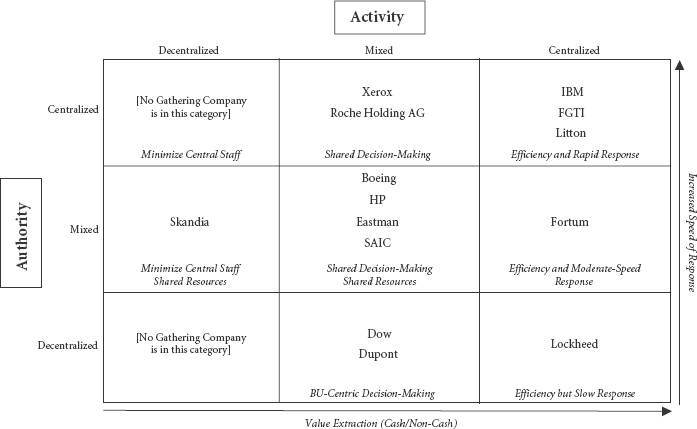

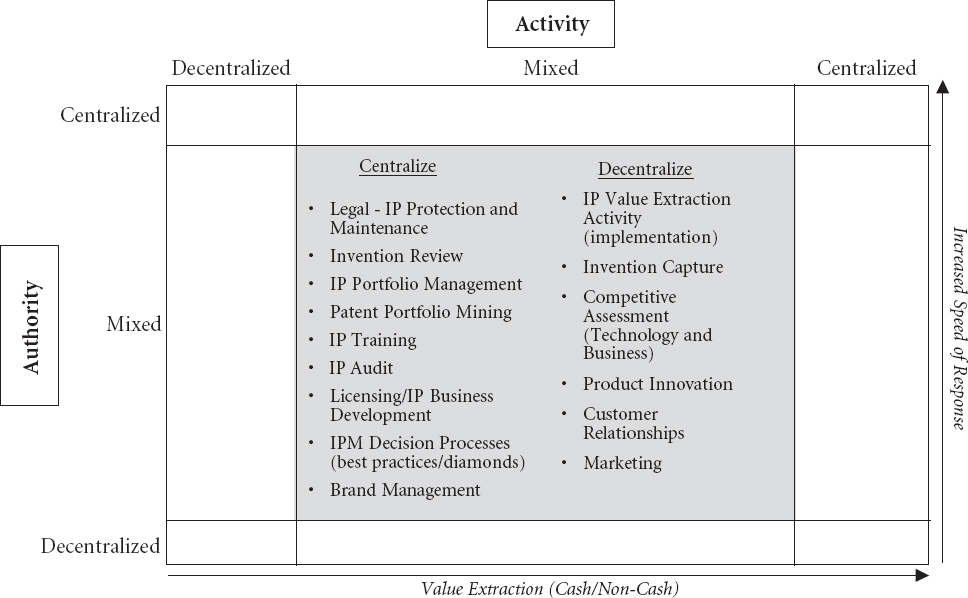

As the first page of Exhibit 3.7 shows, there are at least nine different possibilities we have identified for centralizing or decentralizing the IP management authority and activity within a firm. The second page contains our judgments of where companies we know about might fit on the matrix. The third page of the exhibit highlights the very central cell in the matrix, because its “mixed” approach is arguably the most frequently occurring situation. The exhibit highlights the functions that are centralized as well as those that are decentralized in this popular organizational mode.

Litton recently centralized its IP function after many years of allowing the business units to pursue licenses opportunistically, in support of their unique business interests. Dave Kline recalls the many decisions the company had to make as it centralized. (See Exhibit 3.8.)

For DuPont, decentralizing authority made much more sense. As Bob Gruetzmacher explains:

In DuPont only a licensed patent attorney may actually file a patent application with the PTO or an analogous agency in a foreign country. Notwithstanding that all DuPont patents are assigned to the DuPont Company, the actual responsibility of intellectual property management resides within the respective businesses. Each business pays for, controls, and nurtures its own intellectual property. It makes decisions regarding when and where to file, how to protect (trade secret vs. patent), whether or not to license, or whether or not to abandon. Most IP management groups within business units carry out periodic docket reviews, but not always at the same time frequency. We have a corporate philosophy around filing in countries where there are poor patent enforcement practices. But the ultimate responsibility regarding decisions around intellectual property resides largely within the businesses. This has worked pretty well for us because when you have the businesses paying for the patents, they have the tendency to be a little more discerning when deciding on what to file on, where to file, and what to maintain. Economics and budgets govern the process.

For each company, the decision of how best to organize to extract value will depend on a number of factors, but most importantly the corporate culture and organizational culture.

Best Practice 5: Develop Advanced Screening Criteria

In Level Two, companies began to screen their intellectual property in conjunction with the strategy of the firm. This initial screening was to allow companies to move from patenting everything to patenting things that were strategic to the firm. For Level Two companies, “strategic to the firm” usually related to creating products and services for sale. Now at Level Three, companies have expanded their value extraction horizons beyond the products and services of the firm to include the technologies and know-how of the firm. Here intellectual property has value in the piece of paper or the know-how that can be licensed, sold, or donated. So at Level Three, companies need to widen their screening criteria to include technologies or intellectual assets that may not have a direct value to the firm (i.e., be useful in current or future products or services) but may have indirect value (i.e., can be directly licensed or sold) without having to be embedded in a product or service. Rockwell's Jim O' Shaughnessy, explains:

EXHIBIT 3.8 Centralizing the IP Function

Once we decided to centralize the IP function at Litton, we faced a number of issues. Some of the current issues are: what is the appropriate organization, to whom will it report, and who will report to it; what are the associated functions that will reside within its structure; will it be staffed in-house, outsourced or be a blend of internal and external support; and what business processes and tools will be used? There are a wide variety of new automated tools that perform relatively the same functions but vary considerably in the cost of implementation. The indirect costs need to be carefully considered—i.e., staffing, training, maintenance, etc. Patent search tools such as Aurigin, MAPIT and others, all have considerably different business requirements and arrangements. Which, if any, is right for you depends on your business structure and the way you intend to deploy them.

Other issues to be considered are the initial size and budget and the metrics or “success criteria” established when you start up. Do you want to go “instant on” and immediately address your entire portfolio, or do you want to phase into the business? We all know that the front end of licensing new commodities or technologies doesn't necessarily produce instant financial results as some would lead you to believe. It takes time. What is your business plan and what cash flow profile do you expect to see? What do you have to commit to?

Coming back to the issue of organizational structure and where it will report, this is basically driven by the business objectives and philosophy of the Executive Staff and Board. It is a cultural issue, unique to each corporation, that is governed by the attitudes, mindset and the experience base of those running the show. However, based on many conversations with others, it must report to the highest possible executive level within the company and have the full support of the finance and legal departments. In most companies, “legal” has historically managed this function and, in this new business process, it now becomes an essential support function to the “licensing operation.” In that regard you must have an intimate blend of business and the legal support to provide focus on licensing as the primary business objective rather than protection, which is historically what patents have provided. I quite often meet with the management of other companies that don't have an appreciation for patent licensing vs. patent protection. When engaged in discussion, they find this business approach to be something quite foreign to their normal business thinking.

Some final, but no less critical issues are how existing internal organizations will interface with the licensing operation. These organizations historically generate the IP. Up to this point they have had sole use of the IP and have done the associated licensing. How do you interface these operations into a centralized licensing organization so that they understand their new role and are responsible for its success? This is a major challenge for all companies. It is essential to have the strong continuous support of the operating units and technologists. To accomplish this, these operations should be properly incentivized. This must include inventors and those personnel directly involved in the licensing processes. There are many ways to accomplish this and again it varies from company to company.

They also need to know that this new business has the full support of Corporate Executive management. This can and should be accomplished through directives and formal policy guidance which defines their roles and responsibilities and how the organization will operate. The message needs to be clear and unequivocal from the highest possible level within a company.

David Kline, Litton Industries

Intellectual capital can and must be leveraged. You can create a fund of intellectual capital for about one-tenth the cost of the problem it is solving. In the past at Rockwell, if we had a million-dollar problem to solve, we passed the hat to find one million dollars. It had to come from somewhere so somewhere suffered the loss of one million dollars in capital it could use to support its business or function. We were robbing Peter to pay Paul. We might have solved a problem, but we also denied ourselves an opportunity that may have had greater potential.

Today, if we do the right things, we can actually create, say, a half a million dollars of intellectual capital, and we can substitute that for half a million dollars in financial capital. And in any given transaction, as long as the other party agrees that it's a million dollars in value, it doesn't really matter what the components are: you have accomplished what you needed to accomplish.

But the rabbit in the hat is that you can create half a million in intellectual capital if you're really good for less than $50 thousand. Now, what we've done is taken $450 thousand of pressure off the balance sheet. We can put it someplace else. What's really interesting is that that half a million dollars in value can be used many times over. Because it is intangible, its use doesn't dissipate its intrinsic value.

So when you're through, you may actually get millions of dollars worth of value, transactional value, over the life of the intellectual capital for that same investment of $50 thousand plus perhaps something from the investment.

CONCLUSION: BUILDING BEYOND PROFITS

With such aggressive attempts to increase revenues while reducing costs, IP-rich companies can emulate Thomas Edison's slow but sure journey to the boardroom. But we still have farther to go. Profits are not everything. We have not yet arrived at the boardroom door. More stages are ahead—including the Integrated Level, the next tier in the IP Value Hierarchy.