02

The Firm Foundations

The most important role for financial management in an architecture practice is the prediction of what lies ahead and an ability to communicate that prediction to the management of the practice so that they can respond accordingly. However, it is impossible to make meaningful forecasts if you don’t have accurate historical information available as a starting point. The accounting process needs to show where you are now, and you need to have confidence in what you are being told, because you will construct a complex model of the future and make major decisions based on these foundations.

Basic Book-Keeping

Underpinning the whole financial process is the book-keeping system.

It does not matter if you are a sole practitioner or working in a practice with hundreds of staff, there has to be some reliable way of keeping the financial score. This is of course required by law in any event to satisfy our tax reporting obligations. The smallest of practices with only a few people involved may well be able to get by using simple spreadsheets to record lists of income and expenditure that can be translated into a final set of financial accounts at the end of the year by their accountant. Most practices of more than a few people will choose to use an accounting software package which performs the double-entry book-keeping in the background. These packages will also produce a preliminary Profit and Loss account and Balance Sheet. More sophisticated packages will combine accounting, time recording and project planning and reporting to provide an integrated approach to all of the financial aspects of the practice.

This is the annual statement of income and expenditure that shows whether a practice has made an overall gain on its trading performance. It will show the profit or loss that has been made before tax, the tax charge (if any), and the subsequent profit after tax that is available for distribution to the owners or shareholders.

This is a statement of the total assets and liabilities of the business at a particular point in time (usually the end of the financial year). Assets are divided into fixed assets such as property and equipment and current assets which includes cash in the bank, amounts owed to the practice by its customers and the value of work in progress. The Balance Sheet balances by showing the net asset position and who owns those assets (usually the partners or shareholders of the practice).

Profit and Loss Account – A Definition

Balance Sheet – A Definition

A good book-keeping system will be:

- Simple to operate and maintain – entering information needs to be easy and the transition from one financial period or year to the next needs to be straightforward

- Detailed – containing enough information so that you can find items again later easily

- Logical – with items of a similar nature grouped together (e.g. the office expenses for gas, electricity and water will be next to each other in the accounts list rather than being spread out and mixed up with other types of expense)

- Up to date – credibility is soon lost if financial information is presented that can immediately be shown to be wrong because it is does not reflect the current situation

- Documented – each transaction should have a supporting original document (e.g. invoice or receipt).

Information must be recorded in a timely way, and there are a number of activities that need to happen on a routine basis. Gradually, this builds up over the course of the financial year so that you can produce the final output of the process – the annual accounts. The transactions and events that need to be recorded and a suggested timescale for each are listed opposite.

Daily

Weekly

Monthly

Quarterly

Reconciling your accounts with those of your bank – ensuring that all of the items on the statement have been recorded and that their records and yours agree – is crucial. One of the joys of modern accounting software is that this process can largely be automated. Bank statement data can be downloaded directly from the bank and the accounting software can gradually learn how to book transactions that occur regularly (e.g. the payment of rent).

Monthly Profit Reporting

The gradual collection of all of this financial information is necessary so that you can produce a set of year-end accounts that will satisfy the requirements of all of the various stakeholders in the business.

However, this same information can also be used to provide management information that will allow you to make operating decisions during the course of the year.

There is a distinction to be drawn between the management accounting process and the financial accounting process. The latter aims to give a complete and ‘true and fair view’ of the business and is the most definitive statement of what happened financially during the year. This is produced mainly for compliance purposes and can often take a number of months to be finalised. By contrast, management information needs to be produced as soon after the period to which it relates as possible. Situations can change so rapidly within a practice that information relating to one month that is not available until three weeks after the end of that month (which used to be the norm) is almost of no value. Indeed, it could even be a hindrance because it could lead you to make decisions based on a set of circumstances that no longer apply.

So management information needs to be made available rapidly. I take the view that operating figures must be available within three working days of the end of the month.

There is usually a conscious trade-off between speed and detail. Even in the final published financial statements we do not have a truly accurate picture of events. We always have to make assumptions and exercise judgement about what values to include. Accountancy is an art rather than a science, and in the case of management accounts the chosen style is Impressionism rather than Realism.

You need to ensure that the major elements are reported as accurately as possible, but you do not need to be too concerned about glossing over some of the detail. In most practices the Pareto principle will apply (i.e. that roughly 80 per cent of the effects come from 20 per cent of the causes, as identified by the eponymous Italian philosopher in the 1890s). Expenditure on staff and premises will usually account for the majority of the regular monthly expenses and these amounts can be estimated with a fair degree of accuracy as soon as the month is complete.

Financial data only becomes useful information when it has been understood. It is important to consider the needs and preferences of your audience and to have an appreciation of how they assimilate information. The prime need is to communicate the big picture in as striking a way as possible and in my own practice we have developed a reporting format, shown below, that seems to work well. We call this a ‘flash’ report – in the sense of a newsflash, because it attempts to give the big picture in a rapid way.

The flash report shows the performance in the month just gone, plus the financial YTD each in comparison with the original budget. The differences between the actual and the budget are shown in the variances column. Variances are expressed following the usual convention that a positive value is a ‘good news’ figure, such as higher income than expected or lower expenses, and a negative value shows ‘bad news’ such as a shortage of income or an overrun on expenses.

The monthly report focuses on just a few key elements so that you can see immediately which area, if any, is causing a problem:

- Income: This is shown after allowing for the fees that are being collected for other members of the design team. It is important to ensure that you are only looking at the practice’s own net fee income. You must ensure that you are not seduced into complacency by a healthy-looking turnover figure that is ‘flattered’ by the inclusion of fees that do not really belong to the practice.

- Resources: This includes all of the expenses that relate to people. As well as the direct payroll costs, this should include the add-on employer’s costs such as National Insurance Contributions (NICs), the cost of benefit plans such as life cover and medical insurance and the cost of continuous professional development (CPD) programmes and recruitment.

- Overheads: This sweeps up all of the other categories of expense into one large pot. It is very easy to get bogged down in the detail when it comes to overhead costs. It is of course important to review overheads from time to time to ensure that money is not being wasted. However, it’s unlikely that a significant financial problem in an architectural practice is simply the result of spending too much on overheads. It is far more likely to be a structural issue such as the wrong number or the wrong mix of staff for the work on hand. It is all too easy to avoid facing up to these difficult issues by getting immersed in finding the reasons for a minor overspend on stationery or telephone charges.

The flash report enables you to quickly assimilate if the practice is making a profit or not, where you stand in relation to the budget and whether this is a temporary problem or more of a long-term issue.

In the example shown I would initially observe that net profit for the current month of January was only just over a third of its budgeted target (i.e. £13,000 for pre-tax profit compared with a predicted £35,000). A look at the variances shows that this was largely due to a shortfall in fees of £25,000.

Although there was a saving on resource costs and a small overspend on overheads this did not affect the overall picture. The question to address is why were the fees less than expected?

Any movements in ‘work in progress’ (WIP) are deliberately left out of this report: firstly, because it would slow down the process to work out the change in WIP from month to month; and secondly, because it encourages the practice to remain focused on getting invoices out to clients for the work completed.

Thus, in the example it could well be that the work has been done but the practice has not managed to get the relevant invoice issued before the month-end accounting cut-off, in which case this variance should rectify itself in the following month.

Turning to the cumulative YTD picture, which in the example is at the 10 months point, a different story emerges. Again, starting at the bottom line, you can see that there is a serious pre-tax profit shortfall of £85,000 (£300,000 minus £215,000). But the reasons are different. The variance analysis shows that the practice is actually ahead on fees in the year but has seriously overspent on people costs. There have been some modest savings in the overhead area. Perhaps this issue has already been addressed; the current month figures would seem to suggest that it has, but it does now seem that the financial year will not achieve the profit level that was budgeted, because there are now only two months to go.

Key Performance Indicators

To help with the rapid comprehension of the current financial position I recommend that you track a number of profitability key performance indicators (KPIs) each month at your performance management meeting as follows:

- Turnover by director/partner: This is a broad indicator of how much business the average director is managing on an annual basis. In our practice we aim for an annual turnover of £500,000 per director. This means that with four directors we would expect annual net architectural turnover of £2 million.

- Turnover per fee earner: This is very similar to the director/partner turnover KPI above. We look for a turnover of £100,000 per fee earner per year.

- Profit per director/partner: This KPI looks at the bottom line and works out how much pre-tax profit is being made per director. On a projected turnover of £2 million we would aim for a 12.5 per cent pre-tax profit which is £250,000 which equates to an average profit of £62,500 per director.

- Profit per fee earner: This again mirrors the director equivalent above. We would look for a profit of £15,000 per fee earner.

Each of these KPIs can be compared with the budgeted values and also to the benchmarks published by the RIBA inter-firm comparison.

As with all ratio analysis, the use of KPIs is at its most useful when viewed in terms of a trend rather than in isolation. Circumstances may conspire to make the position at the end of a particular month unrepresentative of the general pattern. Looking at a particular KPI’s performance over a 9- or 12-month period will eliminate this sort of short-term anomaly.

Liquidity KPIs

For most practices there will not be any need to produce a full detailed set of accounts (i.e. Profit and Loss account and Balance Sheet) every month. The Profit and Loss account shows how the practice performed over a period of time, usually the 12-month period that comprises the financial year. The Balance Sheet is a picture of the business as it exists at a particular moment in time, usually at the end of the annual Profit and Loss period. For example, if the financial year runs for 12 months from 1 April to the following 31 March, then the Profit and Loss account is expressed as being for the 12-month period ending 31 March, whereas our Balance Sheet just shows the closing position as at 31 March.

The Balance Sheet is often analysed in terms of the ratios between its different elements. This sort of analysis enables you to see how much the business runs on borrowed money rather than the money invested or retained from the profits of previous years. In particular, it shows whether there is a liquidity problem (i.e. will the business have the cash available to pay its bills as they become due).

It is possible to carry out this sort of analysis from the sort of information that is usually readily available to most practices. For example, in my practice, we have developed liquidity KPIs which we review each month along with the profitability KPIs described above, as follows:

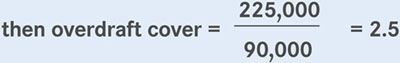

Overdraft Cover

Overdraft cover is a measure that is favoured by many banks, and is often written into overdraft agreements as a condition of the continuation of the facility (known as a bank covenant).

The usual requirement is for a minimum overdraft cover of two times the overdraft limit.

However, it is worth noting that the debtor value used in this calculation needs to be restricted to genuinely recoverable amounts. Many businesses tend to leave unpaid invoice balances on their aged debtor list for many years. Although this can be a useful way of keeping them in mind, it does overstate the amount that the practice can realistically expect to collect. I prefer to keep the aged debtor list as clean as possible and either actively pursue the outstanding debt or acknowledge that it is a dead loss and to write it off.

Current Ratio

The current ratio is a liquidity and efficiency ratio that measures a firm’s ability to pay off its short-term liabilities with its current assets. The current ratio is an important measure of liquidity because short-term liabilities are due within the next year.

This means that a practice has a limited amount of time in order to raise the funds to pay for these liabilities. Companies with larger amounts of current assets will more easily be able to pay off current liabilities when they become due without having to sell off long-term income-generating assets.

The current ratio is calculated by dividing current assets by current liabilities, as shown opposite.

Worked Example: Overdraft Cover

Overdraft cover = Amount owed by clients (debtors)

If, at the end of the month, total amount due from clients = £225,000 and overdraft balance = £90,000

In this example, the overdraft cover is 2.5, which is more than double (2 times) the overdraft limit and therefore would be considered satisfactory.

Worked Example: Current Ratio

If current assets = petty cash + bank balance + debts + WIP

| = £500 + £20,000 + £100,000 + £75,000 | = £195,500 |

| and current liabilities = short term liabilities of payroll, bank overdraft and short-term loans, taxes and suppliers | = £150,000 |

In this example, the current ratio is 1.30, which is above 1 and therefore would be considered satisfactory.

Clearly, the higher the value of the current ratio the better and this is an indicator of how much the practice is operating on a ‘hand-to-mouth’ basis.

The Quick Ratio or Acid Test

The quick ratio (or acid test ratio) is a liquidity ratio that measures the ability of a company to pay its current liabilities when they come due using only ‘quick’ assets. Quick assets are current assets that can be converted to cash within the short-term, which is usually defined as within 90 days. Cash in the bank, petty cash on hand and the amounts owed by our clients (debtors) are considered to be quick assets.

Worked Example: Quick Ratio (Acid Test Ratio)

Taking the same values used in the previous example:

| petty cash + bank balance + debts = £500 + £20,000 + £100,000 = | £120,500 |

and

| short-term liabilities of payroll, taxes and suppliers = | £95,000 |

In this example, the quick ratio is 1.27, which is above 1 and therefore would be considered satisfactory.

The quick ratio is often called the acid test ratio in reference to the historical use of acid to test metals for gold by the early miners. If the metal passed the acid test, it was pure gold. If metal failed the acid test by corroding from the acid, it was a base metal and of no value.

The acid test of finance shows how well a company can quickly convert its assets into cash in order to pay off its current liabilities. It also shows the level of quick assets to current liabilities.

It is increasingly common to see these liquidity ratios being used as KPIs in public sector pre-qualification questionnaires. If a practice fails these simple balance sheet analysis tests their application to work on the project is eliminated immediately before any consideration is given to their architectural skills or experience. A ratio of less than 1 is taken as a sign of financial fragility, which the commissioning body considers to be too great a risk to the fulfilment of the project overall.

Summary

- The financial manager needs to look ahead and predict what the financial future holds for the practice. The accounting process aims to provide an accurate picture of the current financial position of the practice.

- A sound book-keeping system that is simple to use and keep up to date is essential.

- There is a difference between producing figures for management purposes and producing data to satisfy the legal requirements of HMRC and Companies House. The emphasis in the production of management information is on the speed of reporting, so a degree of estimation is acceptable as long as the overall impression is accurate.

- The aim of management information is to facilitate rapid action to remedy a situation before it develops into too great a problem.

- Accurate figures for income and outgoings on people and property provide a fairly good picture of the profitability of the practice in that period of time.

- KPIs can be used to assess quickly which areas, if any, are a problem and need to be addressed.

- KPIs cover not just measures of turnover and profits but also of financing and liquidity. Each practice can evolve its own KPIs to suit its particular market and organisational needs.