CHAPTER 11

Mutual Funds, ETFs, and Pension Funds

INTRODUCTION

What is a mutual fund? A mutual fund can be defined as a collection of stocks, bonds, or other securities such as precious metals and real estate that is purchased by a pool of individual investors and managed by a professional investment company.

When investors make an investment in a mutual fund, their money is pooled with that of other investors who have chosen to invest in the fund. The pooled sum is used to build an investment portfolio if the fund is just commencing its operations, or to expand its portfolio if it is already in business. All investors receive shares of the fund in proportion to the amount of money they have invested. Every share that an investor owns represents a proportional interest in the portfolio of securities managed by the fund.

When a fund is offering shares for the first time, known as an IPO, the shares will be issued at par. Subsequent issues of shares will be made at a price that is based on what is known as the Net Asset Value (NAV) of the fund. The Net Asset Value of a fund at any point in time is equal to the total value of all securities in its portfolio less any outstanding liabilities, divided by the total number of shares issued by the firm.

The NAV will fluctuate from day to day as the value of the securities held by the fund changes. On a given day, from the perspective of shareholders, the NAV may be higher or lower than the price that they paid per share at the time of acquisition. Thus, just like the shareholders of a corporation, mutual fund owners share in the profits and losses as well as in the income and expenses of the fund.

PROS AND CONS OF INVESTING IN A FUND

Why would investors prefer to invest in a mutual fund rather than invest directly in financial assets using the secondary markets? First, as compared to a typical individual investor, a mutual fund by definition has a large amount of funds at its disposal. Consequently, given the size of its typical investment, its transactions costs tend to be much lower. Such costs need to be measured not just in terms of the commissions which have to be paid every time a security is bought or sold, but also in terms of the time required to manage a portfolio. To handle a portfolio successfully, an enormous amount of research is required and elaborate records have to be maintained. This is particularly important from the standpoint of investors who seek to build a well-diversified portfolio of financial assets. The costs involved in investing a limited amount of funds across a spectrum of assets can be prohibitive. On the other hand, by investing in the shares of a mutual fund, investors effectively ensure that their money is invested across a pool of assets, while at the same time they are able to take advantage of reduced transactions costs. Yet another feature of mutual funds is that they can afford to employ a team of well-qualified and experienced professionals who can evaluate the merits of investment in a particular asset before committing funds. Most individual investors lack such expertise, and cannot afford to hire the services of people with such skill sets.

Mutual funds diversify their assets by investing in a number of securities. Individual investors can, if they so desire, take diversification one step further by investing in funds promoted by several different investment companies. Most funds engage full-time investment managers who are responsible for obtaining and conducting the needed research and financial analyses required to select the securities that are to be included in the fund's portfolio. Fund managers are responsible for all facets of the fund's portfolio such as: asset diversification; buying and selling decisions; risk-return tradeoffs; investment performance; and nitty-gritty details involved in providing periodic account statements and end-of-the-year tax data to the shareholders.

Liquidity is another of the major benefits of investing in a mutual fund. If the market for a stock or a bond is not very deep, an investor holding such a security may not be able to sell it easily and quickly. It may often be easier to sell the shares of a mutual fund that has invested in such shares and bonds.

Investing in a mutual fund, however, is not without its disadvantages. First, investors in a mutual fund have no control over the cost of investing in the market. As long as they remain invested in a fund, they have to pay the required investment management fees. In practice, such fees must be continued to be paid even though the value of the assets of the fund may be declining. Moreover, mutual funds incur sales and marketing expenditures, which will eventually get passed on to the investors, as you will see shortly. An individual investing alone will obviously not have to incur such costs. Second, when investors invest in securities via the mutual fund route, they are delegating the choice of securities to be held to the professional fund manager. Thus, investors lose the option to design a portfolio to meet their specific objectives. This may not be satisfactory for High-Net-Worth (HNW) investors or corporate investors. In practice, mutual fund managers try to remedy this shortcoming by offering a number of different schemes, which are essentially a family of funds in which each member fund has been set up with a different objective.

The availability of this kind of a choice may itself pose a problem to certain investors. They may once again need expert advice regarding which scheme to select, as in a situation where an investor is contemplating which financial security to invest in.

SHARES AND UNITS

In the United States, mutual funds are set up as companies and issue shares to their investors. In some countries, the funds are set up as trusts and consequently issue units to their investors. We will use the terms shares and units interchangeably.

OPEN-END VERSUS CLOSED-END FUNDS

In the case of an open-end fund, investors can buy or sell shares of the fund from/to the fund itself at any point in time. The purchase/sale price at which they can transact is called the Net Asset Value (NAV). The NAV of a fund is determined once daily at the close of trading on that day. All new investments into the fund or withdrawals from the fund in the course of a day are priced at the NAV that was computed at the close of that day. As the market prices of the securities in which a fund has invested fluctuate, so will the NAV and the total value of the fund.

The number of shares outstanding at any point in time can subsequently either go up or go down, depending on whether additional shares are issued, or existing shares repurchased. In other words, the unit capital of an open-end fund is not fixed but variable. The fund size and its investable corpus will go up if the number of new subscriptions by new/existing investors exceeds the number of redemptions by existing investors. The fund size and corpus, however, will stand reduced if the redemptions exceed the fresh subscriptions.

An open-end fund need not always stand ready to issue fresh shares. Many successful funds stop further subscriptions after they reach a target size. This would be the case if they were to feel that further growth cannot be managed without adversely affecting the profitability of the fund; however, open-end funds rarely deny investors the facility to redeem shares held by them.

Every mutual fund will maintain a cash reserve that is usually about 5% of the total assets of the firm. These funds are reserved to cover shareholders' redemption requests. Should the amount required for redemption exceed the money available, however, the fund manager will have to liquidate some of the securities to obtain the necessary cash.

Closed-end funds, also known as publicly traded investment funds, are similar to open-end funds in the sense that they too provide professional expertise and portfolio diversification; however, such funds make a one-time sale of a fixed number of shares at the time of the IPO. Consequently, their unit capital remains fixed. Unlike open-end funds, they do not allow investors to buy or redeem units from/with them. In order to provide liquidity to investors, however, many closed-end funds list themselves on a stock exchange. If a fund were to be listed on an exchange, then investors can buy and sell its shares through a broker, just the way they buy and sell shares of other listed companies. The price of a fund's shares need not be equal to its NAV in this case. The shares may trade at a discount or a premium to the NAV based on the investors' perceptions about its future performance and other market factors affecting its shares' demand or supply. Shares selling below the NAV are said to be trading at a discount, while those trading above the NAV are said to be trading at a premium. Shares of unlisted closed-end funds can be traded over the counter.

The fund charters of closed-end funds contain what are called life boat provisions. These provisions require such funds to take action in cases where the shares are trading at a substantial discount to the NAV, by either buying back the shares via a tender offer or converting the fund to an open-ended structure. If the fund managers fail to respond in an appropriate fashion, dissident shareholders can buy large blocks of shares and initiate a proxy fight in order to either liquidate the assets of the fund or make it open-ended.

A critical feature of such funds is that the subscribers to the IPO bear the entire cost of underwriting and marketing incurred by the fund at the time of the issue. This is because the fund's investable corpus at the outset is equal to the amount raised via the IPO less the issuance costs. Such costs include selling fees paid to the retail brokerage firms that sell the shares to the public. The high commission rates on offer provide a strong incentive to brokers to recommend these funds to their clients. At the same time, because they can reduce the investable corpus substantially, these commissions provide a disincentive to the potential investors from the standpoint of subscribing to the IPO.

PREMIUM/DISCOUNT OF A CLOSED-END FUND

The premium or discount of a fund may be calculated as

Thus, if the NAV is $20 and the price in the market is $19, the discount is

UNIT TRUSTS

Unit trusts, also known as unit investment trusts, are similar to closed-end funds in the sense that they are capitalized only once and consequently their unit capital remains fixed. Most unit trusts usually invest in bonds; however, they differ from a conventional mutual fund in one critical respect. Once the portfolio of securities (bonds) is assembled by the sponsor of the unit trust, where the sponsor is usually a brokerage firm or a bond underwriter, the bonds are held until they are redeemed by the issuer of the debt. Thus, there is no trading of the securities that comprise the portfolio held by a unit trust. Usually, the only time the trustee of a unit trust can sell a bond held by the trust is if there is a significant decline in the credit quality of the issue. Due to the lack of active trading, the cost of operating a unit trust is considerably less than the costs incurred by open-end and closed-end funds. Second, most unit trusts have a fixed termination date. And finally, unlike an investor in a mutual fund who is constantly exposed to a changing portfolio composition, an investor in a unit trust knows from the outset the exact composition of the investment portfolio of the trust. In some markets, such funds are referred to as fixed maturity plans.

CALCULATING THE NAV

A mutual fund is a common investment vehicle in the sense that the assets of the fund belong directly to the investors. Investors' subscriptions are accounted for as unit capital. The investments made by the fund constitute the assets. In addition, there will be other assets and liabilities.

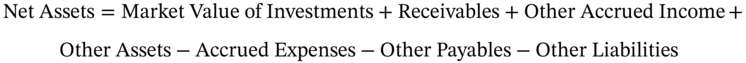

The net assets of a fund is defined as:

The NAV is defined as Net Assets ÷ No. of Units outstanding.

A fund's NAV is affected by four sets of factors:

- Purchase and sale of investment securities

- Valuation of all investment securities held

- Other assets and liabilities

- Units sold or redeemed

The term other assets includes any income due to the fund but not received as on the valuation date, for example, dividends that have been announced by a company whose shares the fund is holding, but are yet to be received. Other liabilities have to include expenses payable by the fund, such as custodian fees or even the management fee that is payable to the Asset Management Company (AMC). These income and expenditure items have to be accrued and included in the computation of the NAV.

An AMC may incur many expenses specifically for given schemes and other expenses that are common to all schemes. All expenses should be clearly identified and allocated to the individual schemes. The expenses may be broadly categorized as:

- Investment management and advisory fees

- Initial expenses of launching schemes

- Recurring expenses

When a scheme is first launched, the AMC will incur significant expenditure, the benefit of which will accrue over many years. Thus, the entire expenditure cannot be charged to a scheme in the first year itself, and has to be amortized over a period of time; however, issue expenses incurred during the life of a scheme cannot be amortized. The unamortized portion of initial issue expenses shall be included for NAV calculation, and will be classified under other assets. Investment advisory fees cannot, however, be claimed on such assets.

COSTS

The costs borne by an investor in a mutual fund can be classified under two heads. The first is what is known as a sales charge or a shareholder fee. This is a one-time charge that is debited to the investor at the time of a transaction, which could be in the form of a purchase, a redemption, or as an exchange of shares of one fund for that of another, which is termed a switch. The amount of the sales charge would depend on the method adopted for distributing the shares. The second category of costs is the annual operating expense incurred by the fund, which is called the expense ratio. The largest component of this expense is the investment management fee. This cost is of course independent of the method adopted for the distribution of shares.

SALES CHARGES

Traditionally there have been two routes for distributing the shares of a mutual fund. They could either be sold using a sales force (or a wholesale distributor) or they could be sold directly. The first method necessarily requires an intermediary, such as an agent, a stockbroker, an insurance agent, or other similar entity, who is capable of providing investment advice to the client and capable of servicing the investment subsequently. This can be construed as an active approach, in the sense that the “fund is sold and not bought.”

In the case of the direct approach, however, there is no intermediary or salesman who will actively approach the client, provide advice and service, and possibly make a sale. Rather, the client in such a situation will directly contact the fund (usually by calling a toll-free number) in response to an advertisement or information obtained elsewhere. In such cases, little or no investment advice is provided either initially or subsequently. This can therefore be termed as a passive approach, in the sense that the “fund is bought and not sold.” It must be remembered that even though a fund may adopt a passive approach for selling its shares, it may nevertheless advertise aggressively.

Clearly, the agent-based system comes with an attached cost. The cost is a sales charge which has to be borne by the client, and which constitutes a fee for the services rendered by the agent. The sales charges levied by such funds are referred to as loads.

The traditional practice has been to deduct this load up front from the investor's initial contribution at the time of his entry into the fund and pass it on to the agent/distributor. The remainder constitutes the net amount that is investable in the fund in the name of the client. This method is known as front-end loading, and the corresponding loads as front-end or entry loads. Because the amount paid by the investor per share exceeds the NAV of the fund, such funds are said to be “purchased above the NAV.”

On the other hand, a mutual fund that sells directly would not incur the payment of a sales charge, because there is no role for an intermediary. Such funds are therefore known as no-load mutual funds. In this case, the entire amount paid by investors will be invested in the fund in their name. Consequently, such funds are said to be “purchased at the NAV.”

It was thought at one point in time that load funds would become obsolete and that the mutual fund industry would come to be dominated by no-load funds. The underlying rationale for this argument is of course that no rational investor would like to pay a sales charge if the same can be avoided. It was felt that individual investors, given their increasing levels of sophistication, would prefer to make their own investment decisions, rather than rely on agents for advice and service; however, the subsequent trend has been to the contrary. There are two reasons why load funds continue to be popular with investors.

First, many investors have remained dependent on the counsel, service, and more importantly, the initiative of investment agents. Second, load funds have shown a lot of ingenuity and flexibility in devising new methods for imposing the sales charge that serve the purpose of compensating the agent/distributor, without appearing to be a burden for the investors. These innovations have come in the form of back-end loads and level loads. Unlike a front-end load, which is imposed at the time of an investor's entry into a fund, a back-end or exit load is imposed at the time of redemption of shares. The advantage of this approach is that the entire investment made by the investor is ploughed into the fund without being subject to an up-front deduction.

Yet another variant is the level load. In this case, a uniform sales charge is imposed every year. Consequently, the reported NAVs would be lower than what they would have been in the absence of a sales charge. In this case also, however, the entire amount paid by the investor at the outset would be investable in the securities held by the fund. Level loads appeal to investors who are more comfortable with the concept of an annual fee (so called fee-based planners) rather than commissions, irrespective of whether these are payable at entry or on exit.

The most common form of an exit load is the contingent deferred sales charge. This approach imposes a load on withdrawal, which is a function of the number of years that the investor has stayed with the fund. Obviously, the longer an investor stays invested, the lower will be the load on redemption. For instance, a 3,3,2,2,1,1,0 contingent deferred sales charge would mean that a 3% load would be imposed if the shares are redeemed within two years, a 2% load if the shares are redeemed after two years but within four years, and a 1% load if the redemption takes place after four years but within six years. Obviously, there is no sales charge if the redemption occurs at the end of six years or thereafter.

Many mutual fund families often offer their funds with a choice of loading mechanisms and allow the distributor and the client to pick the method of their choice. Shares subject to front-end loads are usually called A shares; those subject to back-end loads are known as B shares; while those for which a level load is applicable are known as C shares.

In the case of funds with front-end and back-end loads, the declared NAV will not include the load. Thus, in the case of funds that impose a front-end load, investors must add the load amount per share to the NAV per share in order to calculate their purchase price. Similarly, in the case of a back-end load fund, investors have to deduct the load amount per share from the NAV per share in order to know their net sale proceeds.

Exit loads too can be levied in two ways. If the load is x%, the NAV can be multiplied by 1 − x or divided by 1 + x. Here is an example.

The impact of loads can be better appreciated by comparing investments in load and no-load funds with the same NAV.

A load can be charged by open-end and closed-end funds. It should also be remembered that loads represent issue expenses, which are just one component of the expenses incurred by the fund. A mutual fund incurs other expenses, such as the fund managers' fees, which are charged to the investors on an ongoing basis. The impact of such deductions will be reflected in the form of a lower reported NAV.

PRICE QUOTES

Financial sources often publish two prices for a mutual fund. The lower price is what is applicable for an investor who is redeeming shares, while the higher price applies to someone who is acquiring shares. If there is a single price, it means that it is a no-load fund. In the case of funds with an entry load or an exit load, or both, the purchase price will be higher than the sale price.

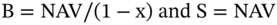

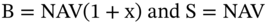

If we denote the purchase price by B and the sale price by S, the load may be computed as (B − S)/B in the following cases.

- Case-1: An entry load of x% is applied as NAV/(1 − x)

Thus

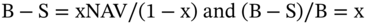

- Case-2: An exit load of x% is applied as NAV(1 − x)

Thus

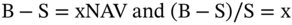

, while

, while

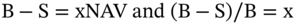

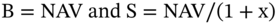

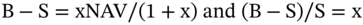

If, however, the entry load is applied as NAV(1 + x) or an exit load as NAV/(1 + x), the formula for the load is (B − S)/S.

- Case-3: An entry load of x% is applied as NAV(1 + x)

So

- Case-4: An exit load of x% is applied as NAV/(1 + x)

Thus

ANNUAL OPERATING EXPENSES

The operating expense is debited annually from the investor's fund balance by the sponsor of the fund. The three main categories of such expenses are the management fee, the distribution fee, and other expenses. These expenses will be mentioned in the prospectus. Thus, it is important to read the prospectus carefully before investing money. Everything else being equal, one should seek funds with low operating expenses.

The management fee, also known as the investment advisory fee, is the fee charged by the investment advisor for managing the fund's portfolio. Sometimes the advisor may be from a different company. If so, the sponsor will pass on some or all of the management fee to the advisor. The fees charged would depend on the type of fund, and as is to be expected, the greater the efforts and skills required to manage the fund, the higher will be the management fee that is charged.

In 1980, in the United States, the SEC approved the imposition of a fixed annual fee called the 12b-1 fee. This is intended to cover distribution costs, including continuing agent compensation and the fund's marketing and advertising expenses. This fee may include a service fee to compensate sales professionals for providing services or for maintaining shareholders' accounts. The amount, which accrues to the selling agent, is to provide an incentive to continue to service the accounts even after having received a transaction-based fee such as a front-end load. This component of the 12b-1 fee is therefore applicable for sales-force-sold load funds and not for directly sold no-load funds. The balance of the 12b-1 fee, which accrues to the fund sponsor, is intended to provide it with an incentive to continue advertising and marketing efforts.

The sum total of the annual management fee, the annual distribution fee, and other annual expenses like the ones described earlier is called the expense ratio.

A fund that tracks an established market index like the S&P 500 is relatively easier to manage as compared to a fund that entails the active implementation of a proactive rebalancing strategy. Thus, it is not surprising that an index fund has the lowest management fee, whereas an actively managed pure stock fund has the highest fee.

SWITCHING FEES

For many years there was no charge for switching from one mutual fund to another within the same family. But these days, some funds have started to charge a flat fee. In many cases, the fee becomes payable once a pre-fixed number of switches for the year is exceeded. These funds justify such charges by arguing that these are being levied to discourage frequent switching. They may have a point because frequent switching of funds increases the administrative costs involved in keeping track of customer accounts. These charges are directly recovered from the shareholder, and do not therefore impact the NAV.

DIVIDEND OPTIONS

Mutual funds usually offer their investors three alternatives from the standpoint of dividends. The first is a dividend option. In this case, the investors periodically get cash inflows, as in the case of equity shares. The second is termed a dividend reinvestment option. In this case, while the fund will declare a dividend, it will not be paid out in the form of cash. What will happen is that an equivalent number of shares, based on the prevailing NAV, will be credited to the investor's account. Thus, the number of shares held by an investor will steadily increase, as the dividends are declared. The third option is termed as the growth option. In this case, no dividends are declared. What happens is that any income and profits earned by the fund are plowed back into the fund. An investor who needs cash can always sell some of the shares in the case of the dividend reinvestment and the growth options.

The option chosen has no consequences for the returns in the first year of investment. But in subsequent years the returns will be different, as we will demonstrate.

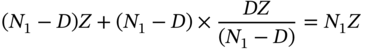

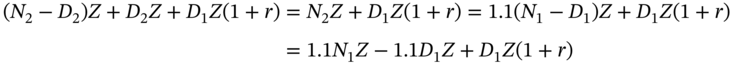

In the case of the dividend and dividend reinvestment options, the share prices will fall when a dividend is paid, as is the case for equity shares. Consider an investor who owns Z shares of a mutual fund. The NAV at the outset is N0. Assume the NAV at the end of the year is N1. The DPS is $D. If the investor chose the growth option, the value of the portfolio will be N1Z. If a dividend option is chosen, the ex-dividend NAV is N1 − D. The portfolio value will be ![]() . In the case of the dividend reinvestment option, the number of additional shares allotted is DZ/(N1−D). Thus, the value of the portfolio is

. In the case of the dividend reinvestment option, the number of additional shares allotted is DZ/(N1−D). Thus, the value of the portfolio is

Thus, the value of the investment is the same in all three cases.

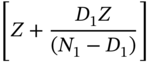

Now assume that at the end of the following year the NAV is 10% higher than the NAV at the end of the previous year, and that the dividend for the year is D2. The value of the portfolio in the case of the growth option is ![]() . If the dividend reinvestment option is chosen, the post dividend NAV at the end of the previous year would be N1 − D1.1 Thus, the NAV at the end of the second year is 1.1(N1 − D1). The number of shares held at the end of the previous year would be

. If the dividend reinvestment option is chosen, the post dividend NAV at the end of the previous year would be N1 − D1.1 Thus, the NAV at the end of the second year is 1.1(N1 − D1). The number of shares held at the end of the previous year would be

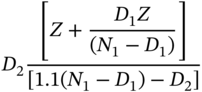

The dividend for the second year is D2. The additional number of shares allocated is

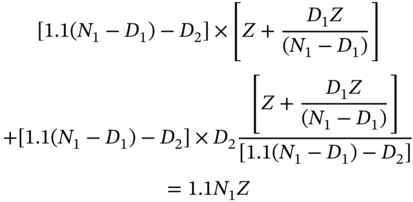

The value of the total shares is

Thus, the terminal value, after two years, is identical in both cases.

Now consider the dividend option. The number of shares is Z. The dividend in the second year is D2. Thus, the total dividend is D2Z. The dividend earned in the first year is D1Z. Its future value assuming a reinvestment at the rate of r% is D1Z(1 + r). The value of the shares at the end of the second year is (N2−D2)Z. Thus, the total value is

In practice, the reinvestment rate for the investor is likely to be less than the 10% growth rate for the mutual fund. Thus, it is likely to be the case that 1.1N1Z – 1.1D1Z + D1Z(1 + r) < 1.1N1Z. Hence the investor stands to get a lower return as compared to the growth and dividend reinvestment options.

TYPES OF MUTUAL FUNDS

We have examined a general classification of mutual funds as open-end versus closed-end, and as no-load versus load funds. Mutual funds can also be distinguished from each other based on their investment objectives and on the types of securities that they invest in.

Once upon a time, mutual fund investments were perceived to be attractive because of two factors. First, they made it easier to hold a well-diversified portfolio. Second, they operated with the services of professional analysts whose services are by and large inaccessible to individual investors. Today, the industry has become highly specialized and funds offer enormous diversity. Investors can therefore easily choose a fund to meet their specific objectives. This is important because no two investors are exactly alike. Some may be conservative while others may be aggressive. While one person may seek a tax-free investment option, another may be quite prepared to invest in a taxable fund. Besides, while most investors are likely to be content with domestic portfolio options, some may seek to hold globally diversified portfolios.

Categorization by Nature of Investments

Mutual funds may invest in equity shares, bonds, or other fixed-income securities of a long-term nature, or in short-term money market instruments. Consequently, we have equity funds, bond funds, and money market funds. There are also funds that invest in physical rather than financial assets. Hence, we have precious metals funds, real estate funds, and so on.

Categorization by Investment Objectives

Different funds have their own investment objectives and consequently cater to different clienteles. Growth funds invest in order to get capital appreciation in the medium- to long-term. Income funds focus on earning regular income and are less concerned with capital appreciation. Value funds are those that invest in equities perceived to be undervalued, and which are consequently expected to rise in price with the passage of time.

Categorization by Risk Profile

Equity funds have a greater risk of capital loss than debt funds, which seek to protect capital while generating regular income. Money market funds that invest in short-term debt securities are even less exposed to risk as compared to bond funds.

Fund managers can create different types of funds to cater to various investor profiles by mixing investments across categories. For example, equity income funds tend to invest in shares that do not fluctuate much in terms of value, but tend to provide dividends on a steady basis. Utility companies like power-sector companies will constitute suitable investments for such funds. Balanced funds are those that seek to reduce risk by mixing equity investments with investments in fixed-income securities. They can also be perceived as funds that try to strike a balance between the need for capital appreciation and the requirement for steady income.

Now we will go on to discuss specific types of funds.

MONEY MARKET FUNDS

Such funds invest in securities with one year or less to maturity. Typical securities acquired by such funds include Treasury bills, which are issued by the government, certificates of deposit (which are essentially time deposit receipts issued by banks), and commercial paper, which are IOUs issued by companies. These investments are highly liquid and carry relatively low credit risk. Consequently, in some markets they are known as liquid funds. There is also a category of tax-free money market funds that invest only in municipal securities. Thus, the earnings of these funds are exempt from federal taxes, and in certain cases from state income taxes as well.

These funds are ideal for investors seeking stability of principal, high liquidity, check-writing facilities, and earnings that are as high or higher than those available through bank CDs. And, unlike bank CDs, these funds do not come with early withdrawal penalties.

Money market funds usually declare a dividend on a daily basis. Consequently, their NAV stays close to the face value at the time of issue.

While these funds pose a low level of risk, regulators in countries like the United States have sought to provide additional safety by requiring such funds to hold a portfolio whose securities have a weighted average time to maturity, that is, substantially less than one year. Money market securities, it must be remembered, have a maximum time to maturity of one year.

GILT FUNDS

A gilt security is a fixed-income security issued by the government, with a term to maturity of more than one year. In ancient England, government bonds were issued with a border made of gold foil, and hence the name. Gilt funds carry little default risk; however, such securities are subject to interest rate or market risk, in the sense that changes in the interest rate structure in the economy can lead to substantial fluctuations in the values of such assets. As can be appreciated, default risk is not the only risk faced by an investor in bonds.

DEBT FUNDS

These funds, also known as income funds, invest in fixed-income securities issued not only by governments, but also those issued by private companies, banks and financial institutions, and other entities like infrastructure companies and public utilities.

These instruments carry lower risk as compared to equities and tend to provide stable income. Compared to a money market fund, however, a debt fund has greater market risk, as well as credit risk. Compared with gilt funds, on the other hand, these funds have higher credit risk.

Debt funds are known as income funds because their focus is primarily on earning high income, and not on capital appreciation. These funds therefore distribute a substantial part of their surplus to shareholders on a regular basis. We can further subclassify debt funds based on investment objectives.

DIVERSIFIED DEBT FUNDS

A diversified debt fund is defined as one which invests in virtually all types of debt securities issued by entities across all sectors and industries. Although debt securities carry less risk as compared to equities, they nevertheless expose investors to default risk, because they represent contractual obligations on the part of the issuing firm. The advantage of investing in a diversified fund is that the idiosyncratic or firm-specific default risk gets diversified away. Thus, as compared to debt funds that invest only in securities issued by firms in a particular industry or sector of the economy, diversified funds are less risky.

FOCUSED DEBT FUNDS

Such funds tend to invest primarily in debt securities issued by a sector or industry. For instance, there are funds that invest only in corporate bonds and debentures. There are others that choose to invest in tax-free infrastructure bonds or municipal bonds. There are also funds that invest in mortgage-backed securities.

HIGH YIELD DEBT FUNDS

These funds invest in non-investment-grade bonds, or junk bonds. They expose themselves to a higher degree of default risk, in anticipation of greater returns. Such funds are also known as junk bond funds.

DEBT FUNDS AND BOND DURATION

Bonds offer more safety to investors as compared to equity shares, but that does not mean that such funds carry no risk. Whenever a cash flow from a bond is reinvested, there is risk, due to the fact that interest rates in the market may be low at that point in time. This is called reinvestment risk. The other risk is that when a bond is sold, prevailing market yields may be high. If so, the bond would have to be sold at a low price. This is called market risk or price risk.

We have studied bond duration earlier and know that duration is a measure of the interest rate sensitivity of a bond. The higher the duration of a bond portfolio, the greater is the interest rate risk. In practice bond mutual funds are classified along the following lines. As we go down the list, the duration and interest rate risk increase.

- Ultra-Short Duration Funds

- Short Duration Funds

- Medium Duration Funds

- Long Duration Funds

EQUITY FUNDS

Holders of shares issued by equity mutual funds take on much more risk than those who invest in debt mutual funds. Equity funds by definition invest a major portion of their corpus in shares issued by companies. Such shares may be acquired either through the primary market by participating in an initial public offering, a follow-on public offering, or even through a rights issue, or through the secondary market. The value of an equity share fluctuates in practice due to three types of influences: factors specific to the firm itself; factors characteristic of the industry in which the firm operates; and economy-wide factors. Unlike debt instruments, there is no contractual guarantee in terms of dividend distribution or in terms of the safety of the capital invested. Although debt securities will at best repay the original principal invested, however, there is no limit to the possible capital appreciation when one invests in equities.

AGGRESSIVE GROWTH FUNDS

These funds target high capital appreciation and usually take substantial risks in the process. Their investments are highly concentrated in less researched and highly speculative stocks, which are considered to have more growth potential. The potential for high returns, however, is accompanied by enhanced volatility of returns, and consequently by a greater level of risk for investors.

GROWTH FUNDS

Such funds also target companies with a high perceived potential for growth; however, the choice of investments made by such funds tend to be in sunrise sectors like information technology, biotechnology, or pharmaceuticals. The difference, as compared to the case of an aggressive growth fund, is that the stocks chosen tend to be less speculative, although they usually represent a relatively new sector of the economy. Growth funds target high capital appreciation over a medium term.

SPECIALTY FUNDS

These funds have a narrow focus and tend to invest only in companies that conform to certain predefined criteria. For instance, there are funds that will not invest in tobacco or liquor companies. Others selectively target specific regions of the world such as Latin America or the ASEAN countries. Having defined their investment criteria, some funds may choose to hold a diversified portfolio, while others may tend to concentrate their investments in a few chosen securities. Obviously, the returns from the latter will be more volatile. Many years ago, certain funds would not invest in companies that did business with South Africa.

SECTOR FUNDS

These are specialty funds that invest only in a chosen sector or industry such as software, pharmaceuticals, or fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) sectors. As compared to well-diversified funds, these funds carry a higher level of industry-specific risk, if not company-specific risk.

OFFSHORE FUNDS

These funds invest in equities of one or more foreign countries. While international diversification does in principle offer additional opportunities for reducing risk, it also exposes such funds to foreign exchange risk, a factor that is irrelevant for funds that invest solely in domestic securities. A well-diversified offshore fund will invest in more than one country, while a fund with a narrower focus will restrict itself to just a single country.

SMALL CAP EQUITY FUNDS

These funds invest in companies with lower market capitalization as compared to large blue-chip firms. The prices of such firms tend to be more volatile, because the shares are much less liquid. Small cap funds may target aggressive growth or may choose to aim at just a steady level of growth.

Market capitalization is defined as the number of shares outstanding multiplied by the share price. The definition of what constitutes a small cap firm is of course subjective.

OPTION INCOME FUNDS

As the name suggests, these funds write options on securities. Conservative option funds invest in large dividend-paying companies, and then sell options against their stock positions. This strategy ensures a stable income stream on account of two sources: dividend income and premium income.

FUND OF FUNDS

Such a fund is defined as one which invests in other mutual funds. Thus it takes the principle of diversification one level higher. The impact may not be substantial, if the underlying mutual funds themselves are well diversified. The reduction in risk may be perceptible, however, if the underlying funds are narrowly focused.

EQUITY INDEX FUNDS

An index fund tracks the performance of a specific stock market index, such as the Dow Jones Industrial Average or the Standard & Poor's 500 index. Such a fund will invest only in those stocks that constitute the target index, and in exactly the same proportions in which such stocks are present in the index. They can therefore be considered to be mimicking funds. If the index which is being traded represents a large, well-diversified portfolio of assets, then the corresponding fund will have relatively low risk. Such funds reduce operating expenses by eliminating the portfolio fund manager. This is because the stocks in the portfolio rarely change. And even if the relative weights were to change, they will do so in the same way as the weights of the stocks in the index, if the index were to be value weighted. More frequent rebalancing is of course required for funds that track price-weighted or equally weighted indices.

VALUE FUNDS

Growth funds tend to focus on companies with a good or improving prospect for future profits. Their primary aim is therefore capital appreciation. Value funds also seek capital appreciation, but their focus is on fundamentally sound firms that they perceive are undervalued. As compared to growth funds, value funds are usually less risky. Many of these funds tend to invest in a large number of sectors and therefore tend to be diversified; however, value stocks often come from cyclical industries. Shares of cyclical firms may fluctuate more than the overall market in the short run, a phenomenon that can be observed in both bull and bear markets.

EQUITY INCOME FUNDS

These funds invest in companies that give high dividend yields. Their target is high current income with steady, though not spectacular, capital appreciation. Utility stocks are very popular with such funds. The prices of these stocks do not fluctuate much, but they do provide stable dividends.

BALANCED FUNDS

They hold a portfolio consisting of debt instruments, convertible securities, preference shares, and equity shares. They hold more or less equal proportions in debt/money-market instruments, and equities. These funds have the objective of steady income, accompanied by moderate capital appreciation. They are primarily intended for conservative and long-term investors.

ASSET-ALLOCATION FUNDS

By definition, an equity fund will be primarily invested in equities, whereas a debt fund will have its investments concentrated in fixed-income securities. These funds therefore have a fixed or predetermined asset allocation, in the sense that the relative proportions invested in the various categories of securities is preset and will in general not vary. In practice, however, there are funds that follow a variable allocation policy and will flit in and out of various asset classes, such as equities, debt, money market securities, and even nonfinancial assets. Their choice of an asset class would depend on the fund manager's outlook on the market at a given point in time.

COMMODITY FUNDS

These funds specialize in investing in commodity markets. These investments may be made by directly buying physical commodities, by acquiring shares of commodity firms, or by using commodity futures contracts. Specialized funds in this category will focus their attention on a specific commodity or a group of related commodities (for example, edible oils), while diversified commodity funds will spread their investments over many different commodities. Common examples of such funds include gold funds, silver funds, and platinum funds.

REAL ESTATE FUNDS

These funds either invest in real estate directly or fund real estate developers. Funds that invest in housing finance companies and mortgage-backed securities would also fall in this category.

TAX-EXEMPT FUNDS

A fund that invests in tax-exempt securities is known as a tax-exempt fund. In the United States, municipal bonds yield tax-free income, whereas interest paid on corporate bonds is taxable.

RISK CATEGORIES

Depending on their investment objectives, mutual funds can be grouped into various risk categories.

Low Level Risk Funds

- Money market funds

- US T-bill funds

- Insured bond funds

Moderate Level Risks

- Income funds

- Balanced funds

- Growth & Income funds

- Growth funds

- Short-term bond funds

- Intermediate-term bond funds (taxable and tax-free)

- GNMA funds

High Level Risks

- Aggressive Growth funds

- International funds

- Sector funds

- Specialized funds

- Precious metals funds

- High Yield bond funds

- Commodity funds

- Options funds

THE PROSPECTUS

A prospectus is a formal printed document offering to sell a security. Like equity shares and debt securities, mutual funds too are offered with a prospectus to potential investors. The prospectus is required to disclose important information about the security. As a minimum, it must disclose the fund's financial history, its investment objectives, and information about the management.

There are various ways of obtaining a prospectus. It can be obtained from the broker; however, brokers usually handle only load funds. The prospectus can also be obtained by writing to the investment company. And it can always be ordered by calling the fund's toll-free number.

STRUCTURE OF A MUTUAL FUND

A mutual fund is organized as follows. The shareholders, who are the owners of the fund, are represented by a board of directors. These directors are also known as the trustees of the fund. The board governs the mutual fund. Members of the board may be interested or inside directors who are affiliated with the fund, or they may be independent or outside directors not affiliated with the fund in any manner.

The fund's portfolio is managed by an investment adviser or a management company. In practice, the adviser can be an affiliate of a brokerage firm, an insurance company, a bank, an investment management firm, or an independent entity. In addition, many mutual funds will also engage the services of a distributor, whose task it is to sell shares to the public, either directly or through other firms. Such distributors are essentially broker-dealers who may or may not be affiliated with the fund and/or the investment adviser.

The fund is also linked to three external service providers: a custodian, a transfer agent, and an independent public accountant. The role of the custodian is to hold the fund's assets and ensure they are segregated from the accounts of others. Transfer agents perform the task of processing orders at the time of purchase and redemption and transferring securities and cash to the concerned parties. Thus, whenever clients seek to invest in shares or redeem them, they will have to have a transaction with the transfer agent. The agents also collect dividends and coupons and distribute them to the shareholders. The job of the accountant is, of course, to audit the financial statements of the fund.

SERVICES

All mutual funds do not provide the same menu of shareholder services. A complete program of investor services should include at least the following.

Automatic Reinvestment Plan

Most mutual funds offer the option of automatically investing all income and capital gains. This option allows for the easy systematic accumulation of additional shares of the fund. Automatic reinvestment is always a voluntary option. Distributions may always be taken in cash, but the benefits of compounding may be lost. Whether reinvested or taken in the form of cash, however, distributions are subject to certain tax liabilities. In most cases, however, reinvested dividends and capital gains are not subject to loads.

Contractual Accumulation Plan

This kind of a plan requires the investor to commit to purchasing a predetermined fixed dollar amount on a regular basis for a specified period of time. In the case of such plans, the investor gets to decide on the dollar amount, the frequency, and the length of time the plan is to continue. In some countries, these are known as systematic investment plans.

Voluntary Accumulation Plan

In these plans, the shareholder voluntarily purchases additional shares at periodic intervals. Each purchase must meet the fund's minimum investment requirement. With a voluntary plan, the investor can change the amount invested each time, the frequency of investments, and the duration of the plan.

Check Writing

Many mutual funds, and all money market funds, offer the facility of free check-writing. This option is not available for tax-deferred retirement accounts. There is no restriction on how many checks one may write each month, as long as the account balance is not reduced below the minimum required to maintain the account. Each check should be for an amount greater than or equal to the minimum specified by the fund.

Switching Within a Family of Funds

Most investment companies permit shareholders to switch from one fund to another within the family. Usually all that is required is a telephone call from the investor to the fund's toll-free number. In most cases this feature is offered at no cost. Telephone switching is a strategy whereby the investor attempts to capitalize on the cyclical swings in the stock market. It means keeping a substantial amount in stock funds when the market trend is bullish, and switching most of the investment to a money market fund when the market becomes bearish.

Voluntary Withdrawal Plans

These plans require the shareholder to initiate the request for redemptions whenever they desire to withdraw funds. Shareholders may also establish a plan whereby the fund will redeem a prearranged fixed dollar amount to be wired to the shareholder's bank on a monthly, quarterly, semiannual, or annual basis. In some countries, these are known as systematic withdrawal plans.

INVESTMENT TECHNIQUES

Mutual fund investors may employ a variety of techniques from the standpoint of investment. These include dollar-cost averaging, value averaging, and a combination of the two approaches.

Dollar-cost Averaging

In this investment technique one must invest the same amount of dollars at regular intervals. Your dollars will buy more shares when the NAV is low, and less when the NAV is high. Over a period of time, the average price paid per share will always be less than the price paid under a strategy where the investor tries to guess the highs and lows. The major disadvantage of this strategy is that it fails to tell you when to buy, sell, or switch. Thus, the valuable benefit of the switching option is completely lost.

Thus, in dollar-cost averaging the average cost of investment will always be lower than the average NAV over the period. The reason is that when we compute the average investment cost, we are giving higher weight to lower NAV values and lower weight to higher NAV values. In contrast, when we compute the average NAV, all values are given the same weights.

Value Averaging

Value averaging is a more sophisticated yet relatively easy means of increasing the value of your investment over time. In our example, let us assume that you want your investment to increase in value by $250 every quarter.

The Combined Method

One can always combine the features of dollar-cost averaging and value averaging. Investors may wish to invest a fixed amount at the end of every period, and get a targeted appreciation in wealth. For example, let us assume that the investors start with an investment of $1,250 in a money market mutual fund and $1,250 in a stock fund on January 1. Thus, they have invested $2,500 for the quarter. At an NAV of $10, an investment of $1,250 would imply the acquisition of 125 shares. They would like to see the stock fund appreciate by $250 every quarter.

On 31 March, the value of the stock fund will be $1,000, because the NAV by assumption is $8. They would require the stock fund to have a balance of $2,750, which represents the targeted appreciation of $250 and the investment of $1,250 for the quarter. They should now deposit an amount of $750 in the money market fund and $1,750 in the stock fund on April 1. Because the NAV is $8, they will get an additional 218.75 shares of the stock fund. Their total investment in the stock fund corresponds to 343.75 shares. The investment for the quarter is obviously $2,500.

On June 30, the value of the stock fund will be $4,296.875. They would require a balance of $4,250. So, they should invest $2,500 in the money market fund and shift $46.875 from the stock fund to the money market fund on July 1. They will consequently have 340 shares in the stock fund after the divestment. The investment for the quarter is obviously $2,500.

On September 30, the value of the stock fund will be $5,440. They would require a balance of $5,750. So, they should invest $310 in the stock fund and put $2,190 in the money market fund on October 1. The total investment for the period is obviously $2,500.

THE TOTAL RETURN

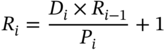

Mutual funds report a statistic called the Total Return. The inherent assumption is that any payouts, by way of dividends or capital gains, are reinvested to acquire additional shares. To calculate the total return for an N-period horizon we need to define the reinvestment factor.

The reinvestment factor for period I, is defined as:

where

- Ri ≡ reinvestment factor for period i. R0 is obviously 1.0.

- Di ≡ payout for period i.

- Pi ≡ NAV at the end of period i.

Consider Table 11.7.

Assume that the dividend payout is $2.50 per share. The reinvestment factor for each year is given in Table 11.8.

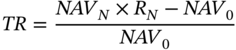

The total return is defined as:

where ![]() .

.

TABLE 11.7 The Year-wise NAVs

| Year | Year-End NAV |

|---|---|

| 0 | 10.00 |

| 1 | 11.00 |

| 2 | 12.50 |

| 3 | 11.50 |

| 4 | 14.00 |

| 5 | 15.00 |

TABLE 11.8 Evolution of the Reinvestment Factor Through Time

| Year | Reinvestment Factor |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1.2273 |

| 2 | 1.2455 |

| 3 | 1.2708 |

| 4 | 1.2269 |

| 5 | 1.2045 |

Thus, in our example, the total return is:

COMPUTATION OF RETURNS

In practice, investors in a mutual fund will not conveniently invest on 1 January of a year and withdraw on 31 December of the same year. They will make multiple investments during the course of the year, and possibly multiple withdrawals as well. If the investors have opted for the dividend option, then they have a choice of taking the payout in the form of cash or reinvesting it back in the fund. In the latter case, there will be no cash receipt, but the number of shares held will increase, which will have implications for future cash flows. In the case of investors who have opted for a dividend reinvestment option, each time a payout is declared, the number of shares held will automatically increase.

We will consider the case of investors who invest at the onset of a calendar year. They receive quarterly dividends and choose to reinvest whatever is received on 31 March and 30 September. The payouts received on 30 June and 31 December are taken in the form of cash.

The NAV at the end of each month and the dividends declared every month are as shown in Table 11.9.

Assume the investors acquire 1,000 shares at the start of the year. At the end of the 4th month, they redeem shares worth $1,650. At the end of the 8th month, they redeem shares worth $1,080. In the 10th month they invest an additional $2,040.

TABLE 11.9 The Dividend Payout and the NAV at the End of Each Month of the Year

| Month | Dividend per Share | Month-End-NAV |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.00 | 10.00 |

| 1 | 0.00 | 10.40 |

| 2 | 0.00 | 10.75 |

| 3 | 1.05 | 10.50 |

| 4 | 0.00 | 11.00 |

| 5 | 0.00 | 11.60 |

| 6 | 1.20 | 12.00 |

| 7 | 0.00 | 11.20 |

| 8 | 0.00 | 10.80 |

| 9 | 2.12 | 10.60 |

| 10 | 0.00 | 10.20 |

| 11 | 0.00 | 10.60 |

| 12 | 1.25 | 10.40 |

TABLE 11.10 The Monthly Cash Flow Schedule for the Investor

| Time | Starting Number of Shares | Ending Number of Shares | Cash Flow |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1,000 | 1,000 | (10,000) |

| 1 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 0.00 |

| 3 | 1,000 | 1,100 | 0.00 |

| 4 | 1,100 | 950 | 1,650 |

| 5 | 950 | 950 | 0.00 |

| 6 | 950 | 950 | 1,140 |

| 7 | 950 | 950 | 0.00 |

| 8 | 950 | 850 | 1,080 |

| 9 | 850 | 1,020 | 0.00 |

| 10 | 1,020 | 1,220 | (2,040) |

| 11 | 1,220 | 1,220 | 0.00 |

| 12 | 1,220 | 0.00 | 14,213 |

Now let's project the monthly cash flows for these investors. Inflows are positive, and outflows are negative. Dividends that are taken in the form of cash will manifest themselves as inflows. Dividends that are reinvested will have no implications for the cash flow at that point in time, but will influence subsequent cash flows. The monthly cash flows are as depicted in Table 11.10.

Analysis

- Month-0: 1,000 shares are acquired at an NAV of 10. Thus, there is an outflow of $10,000.

- Months 1 & 2: No transactions and hence no cash flows.

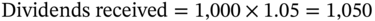

- Month-3:

. This is reinvested at an NAV of 10.50. Thus, 100 additional shares will be received. There is no cash flow at the end of the period, but the number of shares held, increases from 1,000 to 1,100 because of the reinvestment.

. This is reinvested at an NAV of 10.50. Thus, 100 additional shares will be received. There is no cash flow at the end of the period, but the number of shares held, increases from 1,000 to 1,100 because of the reinvestment. - Month-4: Shares worth $1,650 are redeemed. Because the NAV at the end of the month is 11.00, 150 shares have to be sold. Thus, there is an inflow of 1,650 at the end of the month. The number of shares held after redemption is 950.

- Month-5: No transactions and hence no cash flows.

- Month-6:

. This is taken in the form of cash and hence there is an inflow at the end of this month.

. This is taken in the form of cash and hence there is an inflow at the end of this month. - Month-7: No transactions and hence no cash flows.

- Month-8: Shares worth $1,080 are redeemed. Because the NAV at the end of the month is 10.80, 100 shares have to be sold. Thus, there is an inflow of 1,080 at the end of the month. The number of shares held after redemption is 850.

- Month-9:

. This is reinvested at an NAV of 10.60. Thus, 170 additional shares will be received. There is no cash flow at the end of the period, but the number of shares held increases from 850 to 1,020 because of the reinvestment.

. This is reinvested at an NAV of 10.60. Thus, 170 additional shares will be received. There is no cash flow at the end of the period, but the number of shares held increases from 850 to 1,020 because of the reinvestment. - Month-10: An additional 2,040 is invested at an NAV of 10.20. Thus, the number of shares acquired is

. The total number of shares held at the end of the month is 1,220.

. The total number of shares held at the end of the month is 1,220. - Month-11: No transactions and hence no cash flows.

- Month-12:

. The shares can be sold at the NAV of 10.40, which will yield an inflow of 12,688. The total inflow is 14,213.

. The shares can be sold at the NAV of 10.40, which will yield an inflow of 12,688. The total inflow is 14,213.

We can use the IRR function in Excel to compute the rate of return based on the projected cash flow stream. It comes out to be 4.5864% per month. If we convert the monthly rate to a bond equivalent rate, as we did for pass-throughs, we get a figure of 61.75% per annum.

TAXATION ISSUES

In some countries, the dividends received by an investor from a mutual fund are taxed at the hands of the investor. In other countries the mutual fund may have to pay a dividend distribution tax prior to distribution of the payout. If dividends are added to the income of a shareholder and then taxed, the applicable tax rate will be the marginal rate for the investor. In contrast, if a dividend distribution tax is applicable, the tax burden for all shareholders is identical.

If the NAV at the time of sale is higher than what it was at the time of purchase, a capital gains tax may be payable. The rate of tax may depend on whether the investment was short term or long term. There is no hard-and-fast rule as to what is short and what is long. In some countries, an investment of one year or longer is long term, whereas in some others an investor must have held the shares for at least three years for the gains to be classified as long term.

Capital gains taxes may be applicable after providing an indexation benefit. That is, the initial investment may be indexed to a price index such as the CPI, and the prescribed tax rate is applied to the indexed capital gain. This will obviously reduce the effective rate of tax.

At the level of the fund, income received and capital gains/losses may have tax implications. Once again, the capital gains may be classified as short term and long term.

ALTERNATIVES TO MUTUAL FUNDS

While mutual funds represent a popular and easily accessible investment tool for most investors, there are alternatives. In this section we will examine some of the alternatives.

Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs)

Mutual funds, as discussed earlier, have two obvious shortcomings. First, the shares of an open-end fund are priced at, and can be transacted only at, the NAV as calculated at the end of the day. Thus, transactions at intraday prices are ruled out. Second, investors have little control over their tax liabilities. As we discussed, a withdrawal by a group of shareholders can lead to a sale of assets, which can trigger off capital gains taxes for investors who choose to continue to remain invested in the fund.

In response to these perceived shortcomings, exchange-traded funds (ETFs) were introduced in the 1990s. These are open-ended in structure but are traded on stock exchanges just like conventional stocks. They are in a way similar to closed-end funds in the sense that their quoted prices are usually at a small premium to or discount from their NAV. In practice, however, these deviations are limited in the case of ETFs, because of the potential for arbitrage, as we shall shortly demonstrate. Most ETFs are based on popular stock indices. But funds that actively manage portfolios are now available.

The exchange-traded feature of an ETF offers many advantages to the investors. Because ETFs are quoted on stock exchanges, like equity shares and closed-end mutual funds, investors can use a conventional brokerage account to acquire and dispose of shares. Price discovery takes place in a continuous market involving market makers. Potential investors can place a variety of orders like market orders, limit orders, and stop-loss orders. Shares of an ETF can be used for both margin trading and short-selling, as with conventional stocks. ETFs are cheaper than equity mutual funds and even index funds, as measured by their typical expense ratios.

Because ETFs are bought by retail investors through brokers and dealers, all the housekeeping activities pertaining to account management are undertaken by such intermediaries. The fund per se interacts with a small group of brokers and dealers. This brings down the fund management cost considerably.

Conventional mutual funds are much less transparent than ETFs. The former are required to disclose the composition of their portfolios only on a periodic basis, which is typically every quarter. The disclosure is generally made with a lag of a few months. Consequently, investors are not aware of the current composition of the underlying portfolio at any point in time. In contrast, the composition of the underlying portfolio of an ETF is known on a daily basis.

Unlike the shares of an open-end mutual fund, ETF shares cannot be bought from or sold back to the sponsor of the fund. The sponsor, however, will exchange large blocks of ETF shares in kind for the securities of the underlying index plus an amount of cash that represents the accumulated dividends of the fund. This large block of ETF shares is called a creation unit. One creation unit is typically equal to 50,000 ETF shares. Broker-dealers will usually purchase creation units from the fund and break them up into individual shares, which will then be offered on the exchange to individual investors. Broker-dealers and institutions can also redeem ETF shares by assembling creation units and exchanging them with the fund for a basket of securities plus cash.

The ETF deals exclusively with a chosen group of institutional investors known as Authorized Participants or APs. To acquire a creation unit, an AP will acquire shares of the individual assets that constitute the portfolio and exchange them with the fund sponsor. Once a creation unit is acquired in this way, the ETF shares can be sold by the AP to investors, with a lot size of one.

The basket of securities required to acquire a creation unit is known as the creation basket. The reverse, or the redemption of a creation unit, is also possible. An AP can hand over creation units to the sponsor in exchange for a basket of securities, known as the redemption basket.

The sponsor of an ETF will reveal the composition of the creation basket at the start of every trading day. So, the APs know what exactly is required for the acquisition and redemption of creation units.

Thus, if shares of an ETF change hands on a stock exchange, the sponsor of the fund has no role in the process. This is similar to the situation where an investor buys shares of XYZ on the NYSE from another investor. The company that has issued the shares plays no role in the process.

If the price of an ETF share were to diverge significantly from its NAV, then arbitrageurs will step in. If the shares are overpriced, then arbitrageurs will short sell ETF shares and buy creation units from the sponsor to fulfil their delivery obligations. On the other hand, if the shares are underpriced, they will buy ETF shares, assemble them into creation units, and sell them to the sponsor.

ETFs also offer a benefit to investors from the standpoint of taxation, as compared to open-end funds. As illustrated earlier, sale of assets due to a large-scale redemption of shares can lead to capital gains or losses for investors who continue to stay invested. In the case of ETFs, however, the fund can redeem a block of shares by offering the underlying securities in return. This does not constitute a taxable event for the remaining shareholders. Therefore, investors in ETFs are usually subject to capital gains taxes only when they sell their shares in the secondary market at a price higher than the original purchase price. In addition, any cash dividends distributed by ETFs are taxable at the hands of the investor.

The price of an ETF share fluctuates from trade to trade. A potential buyer or seller would like to know if the share price is a fair reflection of the price of the underlying basket of securities. To help investors, ETFs have an arrangement with a third party to compute and publish an intraday value of an ETF share, based on the composition of the creation basket that was disclosed in the morning of that day. This value is published every 15 seconds, and is known as the Intraday Indicative Value (IIV). Others terms for the same include intraday NAV and indication of portfolio value.

Potential Asset Classes

ETFs may be based on a variety of underlying assets. Prominent asset classes include:

- Equity shares

- Fixed Income Securities

- Commodities

- Foreign Currencies

Segregated (Separately Managed) Accounts

Many high-net-worth (HNW) investors dislike mutual funds because of their inability to control their tax liabilities, their inability to influence investment choices, and the absence of “special service.” Money managers offer the facility of separately managed investment accounts for such investors. These are obviously more expensive from the standpoint of the investor as compared to a mutual fund, but they mitigate the problems discussed here. For the money managers, the fee income from such accounts is higher, but so are the service costs.

Pension Plans

A pension plan is a fund that is established for the eventual payment of retirement benefits. The plan may be established or sponsored by (a) a private business entity acting on behalf of its employees – these plans are called corporate or private plans; by (2) federal, state, and local governments acting on behalf of their employees – these are called public plans; and by (3) trade unions acting on behalf of their members. In addition, there are individually sponsored plans that are set up by individuals for themselves.

Pension funds in the United States are essentially financed by contributions by the employer. In some plans, the employer's contribution is matched to some extent by a contribution from the employees. The employer's contributions and a specified amount of the employee's contributions, as well as the earnings of the fund's assets, are tax exempt, provided the plan complies with some governmental regulations. Plans that are given tax exemption are called qualified pension plans. In essence, a pension is a form of employee remuneration for which the employee is not taxed until the funds are withdrawn.

TYPES OF PLANS

There are two basic and widely used types of plans: defined benefit plans and defined contribution plans. There is also a new variant called a cash balance plan, which is a hybrid, in the sense that it combines features of both defined benefit and defined contribution plans.

Defined Benefit Plans

In such plans, the sponsor agrees to make specified payments to qualifying employees beginning at retirement. In the case of death before retirement, some payments are made to nominated beneficiaries. These payments are typically made on a monthly basis. The quantum of the payments is determined by a formula that usually takes into account the length of service of the employee and the earnings. The benefit formula is often based on a fixed percentage of the ending salary for each year of service. From the standpoint of the sponsor, the pension obligation is effectively a debt obligation. Therefore, sponsors of such plans are exposed to the risk that there may be insufficient funds in the plan to satisfy the regular contractual payments that must be made to retired employees.

The employer needs to make a prediction of the future benefits to determine the amount of the contribution. The calculation of the current contributions required to support the promised future payments is made by discounting the projected future cash flows. The entire investment risk in these plans is borne by the employer. That is, as the benefits are assured, the employer faces the risk that the returns on contributions to the plan may not be adequate to make the promised payments.

Actuaries are asked to provide estimates of current pension expenses and the liability of the employer. The following factors are relevant for the computations:

- The age and sex of the employee

- The number of years of service

- The employee's salary

- Anticipated salary increases

- Anticipated employee turnover rates

- Anticipated earnings rate on the plan assets

- Appropriate discount rate

It must be remembered that all estimates involve discretion.

These plans provide an incentive for the employees to stay with the firm until retirement, or at least until the benefits get vested. They also provide an incentive for employees to perform well because the defined benefit is a function of the last salary drawn. The funding status of the plan depends on the difference between the plan assets and the projected benefit obligation.

If the assets exceed the obligation, the plan is said to be overfunded, whereas if the assets are less than the obligation, then the plan is said to be underfunded. If the plan is underfunded, employees may lose earned benefits if the company were to go bankrupt.

A plan sponsor establishing such a plan can use the payments made into the fund to purchase an annuity policy from a life insurance company. Defined benefit plans, which are guaranteed by life insurance companies, are called insured benefit plans. These are not necessarily safer than uninsured plans, because they depend on the ability of the insurance company to make the contractual payments, which is something that cannot be guaranteed.

Benefits become vested when employees reach a certain age and complete enough years of service so that they meet the minimum requirements for receiving benefits upon retirement. The payment of benefits is not contingent upon a participant's continuation with the employer or union. Employees are generally discouraged from quitting, because until the plan is vested, the employee could lose at least the accumulation resulting from the employer's contribution.

Defined Contribution Plans

In the case of such plans, the sponsor is responsible only for making specified contributions into the plan on behalf of qualifying participants and is not responsible for making a guaranteed payment to the employee after retirement. The amount that is contributed in the case of such plans is typically either a percentage of the employee's salary and/or a percentage of the employer's profits.

In this case, the payments made after retirement to qualifying participants would depend on how the assets of the plan have grown over time. In other words, the retirement benefit payments are determined by the performance of the assets in which the contributions made into the plan have been invested. The plan sponsor usually gives the participants various options as to the investment vehicles in which the contributions should be invested.

To the employers, such plans offer the lowest costs and the least administrative problems. The employees also find such plans to be attractive, because they give them some control over how their money is invested. In many cases, participating employees are given an option to invest in one or more of a family of mutual funds.

IRAs

IRA stands for individual retirement account and is a pension plan set up by beneficiaries themselves. Most mutual funds offer tax-deferred retirement plans. These include IRAs and Keogh Plans (meant for the self-employed), The IRA and Keogh plans are subject to certain government regulations. The US government has provided a measure of tax relief for wage earners through IRA and Keogh plans. Both types of plans are intended for individuals. IRA is a personal savings plan that offers tax advantages for setting aside money for one's retirement. In order to qualify one must receive taxable compensation. A Keogh Plan is similar to an IRA, except that it applies to individuals who derive their income from self-employment.

In the case of a traditional IRA, one qualifies for a tax deduction while making a contribution, but taxes must be paid when the money is taken out. Roth IRAs, which became available in 1998, are different. Investors cannot claim a tax deduction on the money that they put in; however, the balance in the account may be withdrawn tax-free at retirement, if the account has been open for at least five years, and the investors have crossed a threshold in terms of age.

CASH BALANCE PLANS

A cash balance plan is basically a defined benefit plan that has some features of a defined contribution plan. It is like a defined benefit plan in the sense that future pension benefits are assured. These benefits are based on a fixed-amount annual employer contribution and a guaranteed annual investment return. Every participant has an account that is credited with a dollar amount periodically, which is generally determined as a percentage of employees' pay. The account is also credited with interest which is linked to some fixed or variable index such as the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Interest is credited at the rate specified in the plan and is not related to the actual investment earnings of the employer's pension trust. Consequently, any gains or losses on the investment accrue to, or are borne by, the employer.

The similarity with a defined contribution plan is that many cash balance plans allow the employee to take a lump-sum payment of vested benefits when terminating their employment with a particular employer, which can then be rolled over into an IRA or to the new employer's plan. In other words, these plans are portable from one employer to another.

Let us say that employees are promised a balance of $600,000 at the time of retirement. Once they retire, employees can take this amount as a lump sum or convert it to an annuity. Every year, the employer will credit the account with a percentage of the annual wage that it pays to the employees. The employer will also credit the account with a fixed percentage of the balance outstanding at the start of the year.

In a defined contribution plan employees will be unsure about the balance in the account at the time of retirement. In the case of a cash balance account, however, they will know it for sure in advance. This feature makes a cash benefit plan resemble a defined benefit plan.

NOTE

- 1 We are denoting the first year's dividend as D1, which we had earlier denoted as D.