CHAPTER 8

Foreign Exchange

INTRODUCTION

The market for the sale and purchase of currencies is an OTC market. That is, there is no organized exchange on which currencies are traded. The largest players in the market are commercial banks. These banks typically provide two-way quotes for a number of currencies; that is, they will quote a bid rate for buying a particular currency and an ask rate for selling the currency. The difference between the two rates, which is called the spread, is a source of profit for the dealer. In the major money centers of the world, some nonbank dealers and large multinational corporations may also don the mantle of dealers. The market in which these entities operate is referred to as the interbank market. The transactions sizes are typically very large, usually of the magnitude of several million US dollars. The retail market for foreign exchange, in which tourists typically transact in the form of currency notes and travelers checks, is characterized by transactions of much smaller magnitudes, and the corresponding bid–ask spreads are also larger.

An exchange rate is the price of one country's currency in terms of that of another. In any bilateral trade there has to be a buyer and a seller. In the foreign exchange market, the words buy/sell, or purchase/sale, are always used from the dealers' perspective. When dealers buy a foreign currency from a client, they will pay out the equivalent in terms of the domestic currency. On the other hand, when dealers sell a foreign currency, they will take the equivalent amount in terms of domestic currency from the client.

CURRENCY CODES

Every currency has a three-character code assigned by the International Standards Organization (ISO). The codes for some of the globally important currencies are given in Table 8.1.

TABLE 8.1 Symbols for Major Currencies

| Country | Currency | Symbol |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | Dollar | AUD |

| Brazil | Real | BRL |

| Canada | Dollar | CAD |

| China | Renminbi Yuan | CNY |

| Czech Republic | Koruna | CAK |

| European Monetary Union | Euro | EUR |

| Hong Kong | Dollar | HKD |

| Hungary | Forint | HUF |

| India | Rupee | INR |

| Israel | Shekel | ILS |

| Japan | Yen | JPY |

| Malaysia | Ringgit | MYR |

| Mexico | Peso | MXN |

| New Zealand | Dollar | NZD |

| Norway | Krone | NOK |

| Poland | Zloty | PLN |

| Russia | Ruble | RUB |

| Singapore | Dollar | SGD |

| South Africa | Rand | ZAR |

| South Korea | Won | KRW |

| Sweden | Krona | SEK |

| Switzerland | Franc | CHF |

| Thailand | Baht | THB |

| UK | Pound Sterling | GBP |

| USA | Dollar | USD |

BASE AND VARIABLE CURRENCIES

While quoting the rate of exchange between two currencies, the obvious practice is to keep the number of units of one currency fixed while making changes in the number of units of the other to reflect changes in the rate of exchange. The currency whose units remain invariant is referred to as the base currency while the other is termed as the variable currency. The practice in the foreign exchange market is to show the ISO codes for the two currencies involved as ABC–XYZ or ABC/XYZ where the first code refers to the base currency and the second to the variable currency. For instance, a quote of 0.8125 USD/EUR or 0.8125 USD–EUR denotes a quote of € 0.8125 per US dollar. Thus, in this quote the US dollar is the base currency while the euro is the variable currency.

DIRECT AND INDIRECT QUOTES

While quoting the exchange rate for a currency it is obviously possible to quote the rate by designating the domestic currency as the base currency or by specifying the foreign currency as the base currency. Exchange quotes where the domestic currency is the variable currency and the foreign currency is the base are referred to as direct quotes. Thus, in London 0.6750 USD–GBP is a direct quote. On the other hand, if the exchange rate were to be specified with the domestic currency as the base currency and the foreign currency as the variable currency, it would be deemed to be an indirect quote. Thus, a quote of 1.425 GBP–USD in London would be an example of an indirect quote.

The reason why we have two systems may be explained as follows. Take the case of a commodity such as wheat. We typically quote the price as dollars per unit of the commodity and not as the number of units of the commodity per dollar. Thus, the standard quote will be something like $5.00 per bushel of wheat and not 0.2000 bushels per dollar. In the currency market, however, we are dealing with two currencies. Consequently, either quoting convention is equally valid; that is, a quote in London may be USD–GBP or GBP–USD. We will briefly consider the indirect method because it is important that readers understand the principle; however, all our illustrations in this chapter will use the direct method.

EUROPEAN TERMS AND AMERICAN TERMS

If an exchange rate were to be quoted with the US dollar as the base currency, then it would be called a quote as per European terms. Thus, a quote of 0.6750 USD–GBP in London would represent a rate as per European terms. An exchange rate with the US dollar as the variable currency, however, will be categorized as a quote as per American terms. For instance, a quote of 1.2500 EUR–USD in NYC would represent a quote as per the American convention. Obviously direct quotes in the United States would be per American terms while indirect quotes will be per European terms. In other countries, quotes for the US dollar where the dollar is represented as the base currency would be termed as European-style quotes while those where the dollar is represented as the variable currency would amount to American-style quotes.

BID AND ASK QUOTES

Let us first consider direct quotes. Consider a quote of 1.2250–1.2375 EUR–USD. The first term represents the rate at which dealers are willing to buy euros from a client, and the second is the rate at which they are willing to sell euros to the client. If dealers have to remain profitable, the rate at which they are prepared to buy the foreign currency – the bid – should be lower than the rate at which they are willing to sell the foreign currency – the ask or offer. Thus, in the case of direct quotes, the bid rate will always be lower than the ask rate.

Now consider a quote of 0.8195–0.8075 USD–EUR. Once again, the first term represents the rate at which dealers are prepared to buy euros from the client, and the second term is the rate at which they are willing to sell euros to a party. Obviously, when acquiring euros from a client, they would want to acquire more per dollar. On the other hand, when selling euros, they would like to part with less per dollar. Thus, it is not surprising that in the indirect quotation system the bid is higher than the ask.

You may still be wondering why the bid is higher than the ask in the case of indirect quotes. The reason is as follows. In a normal price quote, the bid is the rate for buying the base item, while the ask is the rate for selling the base item, both from the dealer's perspective. For instance, a stock broker may quote 80.15 – 80.30 for shares of ABC stock. Thus, if buying shares from a client, the broker will pay 80.15 per share, whereas if asked to sell shares to a client, the broker will charge 80.30 per share.

In a direct foreign exchange quote, the bid is the rate for buying the base currency and the ask is the rate for selling the base currency. Thus, we get the standard result that the bid is lower than the ask. In an indirect quote, however, the bid is the rate for buying the variable currency and the ask is the rate for selling the variable currency. Hence, the bid is higher than the ask. Unlike commodities and other financial assets, in foreign exchange markets both quoting conventions are legitimate.

APPRECIATING AND DEPRECIATING CURRENCIES

If the value of a currency increases in terms of another currency, then it is said to have appreciated. On the other hand, if the value of a currency declines in terms of another, then it is said to have depreciated. It should be noted that appreciation or depreciation of a currency is with respect to another currency. Thus, statements like “the US dollar has appreciated” have no meaning. In order to be meaningful, the currency with respect to which it has appreciated or depreciated should also be specified; for example, “The US dollar has appreciated with respect to the Australian dollar.”

Consider a quote of 1.2250 EUR–USD in NYC. It is obviously a direct quote. If the rate increased to 1.2305 EUR–USD, it would mean that a euro is worth more in terms of dollars. If, however, the rate decreased to 1.2180 EUR–USD, it would mean that a euro is worth less in terms of dollars. An increase in the quote would consequently imply that the euro has appreciated or that the US dollar has depreciated. On the contrary, if the rate declined, it would signify that the euro has depreciated or that the US dollar has appreciated. Thus, in the case of direct quotes, a rising value signifies a depreciating home currency and an appreciating foreign currency, whereas a decline in the rate signifies the opposite.

Now let us consider indirect quotes. Take a quote of 0.8125 USD–EUR. If the rate increases, it would signify that the dollar is worth more in terms of euros, and therefore that the dollar has appreciated or equivalently the euro has depreciated. On the other hand, a fall in the rate would signify that the dollar is worth less in terms of the euro, which would consequently be construed as a depreciation of the dollar with respect to the euro. Hence, in the case of indirect quotes, a rising value signifies an appreciating home currency, whereas a decline in the rate connotes a depreciating home currency.

This does appear confusing at first glance that an increase in the quoted rate connotes a depreciating US dollar in NYC if rates are quoted directly, but it signifies an appreciating dollar if rates are quoted indirectly. The best way to clear up the confusion is to perceive the two currencies involved as base and variable currencies. An increase in the quote always means that the variable currency has depreciated, while a decrease in the quote always means that the variable currency has appreciated. In the case of a direct quote in NYC, the US dollar is the variable currency. Thus, a rising quote with respect to a currency like the euro signifies a depreciating dollar and an appreciating euro, while a declining rate connotes the opposite. On the other hand, in the case of an indirect quote in NYC, the US dollar is the base currency. In this case, a rising quote with respect to a currency like the euro signifies a depreciating euro or an appreciating dollar. A declining value in the case of an indirect quote in NYC would imply a depreciating dollar and an appreciating foreign currency.

What are the implications of an appreciation or depreciation of the US dollar with respect to the euro? An appreciation of the dollar would mean that the price of the euro in terms of dollars has gone down. Consequently, imports from the EU would be more attractive for Americans while imports from the United States would be less attractive for EU consumers. Conversely, a depreciating dollar would lead to a decline in imports from the EU into the United States while boosting US exports to the EU.

CONVERTING DIRECT QUOTES TO INDIRECT QUOTES

Consider a quote of 1.2250–1.2375 EUR–USD offered by Citibank in NYC. It is obviously a direct quote. Consider the bid of 1.2250. If the dealers are prepared to buy euros at dollars 1.2250 per euro, it obviously means they are prepared to sell dollars at 1/1.2250 = 0.8163 euros per dollar. Similarly, the ask rate of 1.2375 is equivalent to a rate of 0.8081 euros per dollar. Thus, the equivalent indirect quote is 0.8163–0.8081 USD–EUR.

The direct quote of 1.2250–1.2375 will have an equivalent direct quote in Frankfurt, where a direct quote will be in terms of euros per dollar. The bid for a dealer in Frankfurt, however, will be a rate for buying US dollars while the ask rate will be a rate for selling dollars. Thus, the equivalent direct quote in Frankfurt is 0.8081–0.8163 USD–EUR.

Thus, to convert a direct quote in a market to an indirect quote in the same market, take reciprocals on both sides. To convert a direct quote in a market to the equivalent direct quote for the foreign currency in its home market, take reciprocals on both sides and interchange the numbers.

POINTS

Consider a quote of 1.2235–1.2295 EUR–USD. Exchange rate quotations in interbank markets are given up to four decimal places. Thus the last digit corresponds to 1/10,000th of the variable currency. The last two digits in such quotes are called points or pips. The first three digits of a quote are known as the big figure. In this case, the big figure is 1.22 and the spread is 60 points.

In the case of certain currencies, the quotes are given up to two decimal places only. Consequently, in such cases a point or pip is 1/100th of the variable currency. For instance, consider a quote of 95.75–96.95 USD–JPY. The spread is 120 points.

RATES OF RETURN

Let S0 be the exchange rate for US dollars in terms of the euro as quoted in Frankfurt. Assume that a year later the exchange rate is S1 USD–EUR. The rate of return for a European trader who acquires a dollar is given by

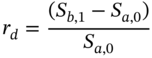

Now consider the issue from the perspective of an American trader who acquires a euro. The price of a euro in terms of the dollar is obviously 1/S0 EUR–USD. Thus the rate of return for the trader is

Thus the percentage change in return depends on the perspective that we take. We have considered the European trader to be the domestic investor and the American trader as the foreign investor. It can be demonstrated that

Thus, one plus the rate of return for a domestic investor is the reciprocal of one plus the rate of return for a foreign investor.

THE IMPACT OF SPREADS ON RETURNS

Assume that the quoted rates for the US dollar in Frankfurt at the beginning and end of a year are as follows.

- 1 January 20XX: Sb0–Sa0 USD–EUR

- 31 December 20XX: Sb1–Sa1 USD–EUR

A European trader can acquire a dollar on 1 January at a price of Sa0, and can sell it after a year at Sb1. The rate of return is

An American trader can acquire a euro on 1 January at 1/Sb,0. A year later the euro can be sold to realize 1/Sa1 dollars. The rate of return is

ARBITRAGE IN SPOT MARKETS

We will consider three types of arbitrage in foreign exchange spot markets: one-point arbitrage, two-point arbitrage, and three-point (or triangular) arbitrage. Let us first look at one-point arbitrage.

ONE-POINT ARBITRAGE

Consider the following quotes in NYC on a given day.

- Citibank: 1.2225–1.2280 EUR–USD

- HSBC: 1.2285–1.2340 EUR–USD

Take the case of an arbitrageur who has 1,000,000 US dollars. The arbitrageur can buy 1,000,000/1.2280 or 814,332.25 euros from Citibank. This can immediately be sold to HSBC at the bid rate of 1.2285 to yield 1.2285 × 814,332.25 = $1,000,407.17. Clearly there is an arbitrage profit of 407.17 dollars.

Consider another situation.

- Citibank: 1.2225–1.2280 EUR–USD

- HSBC: 1.2180–1.2220 EUR–USD

In this case an arbitrageur can acquire 1,000,000/1.2220 or 818,330.61 euros from HSBC. This can immediately be sold to Citibank at its bid rate of 1.2225 to yield $1,000,409.17. Thus, once again there is an arbitrage profit of 409.17 dollars.

Such potential for arbitrage will exist as long as the quotes from competing banks do not overlap by at least one point. Consider the following quotes.

- Citibank: 1.2225–1.2280 EUR–USD

- HSBC: 1.2280–1.2340 EUR–USD

Or

- Citibank: 1.2225–1.2280 EUR–USD

- HSBC: 1.2185–1.2225 EUR–USD

Obviously, there is no scope for arbitrage in either of these two cases.

TWO-POINT ARBITRAGE

Consider the following quote in NYC on a given day.

- Citibank: 1.2225–1.2280 EUR–USD

On the same day BNP Paribas in Paris is quoting 0.8185–0.8220 USD–EUR.

This also represents an arbitrage opportunity although it is not obvious at first glance. Consider the following strategy. Borrow 1,000,000 euros and acquire 1,222,500 USD in NYC. The currency can immediately be sold in Paris to yield 1,000,616.25 euros. Obviously, there is an arbitrage profit of 616.25 euros. What is the cause in this case?

The equivalent direct quote in Paris for Citibank's quote in NYC is 0.8143–0.8180. This is not overlapping with the quote given by BNP, and we know that the two quotes must overlap by at least one point to rule out arbitrage. This kind of an arbitrage opportunity is called a two-point arbitrage. Clearly, two-point arbitrage is a manifestation of one-point arbitrage executed across two markets.

TRIANGULAR ARBITRAGE

Consider the following quotes in Tokyo and NYC respectively.

- Bank of Tokyo: 125.00 EUR–JPY

- 112.50 USD–JPY

- Citibank: 1.1250 EUR–USD

Consider the following strategy. Borrow 1 MM yen in Tokyo and acquire 8,000 euros. The euros can be sold in NYC to yield 9,000 USD. The USD can then be sold in Tokyo to yield 1,012,500 JPY. Obviously, the strategy yields an arbitrage profit of 12,500 JPY. This kind of arbitrage, which entails the use of three currencies, is termed as triangular arbitrage.

There are two ways of acquiring a currency. In this case, USD can be acquired in Tokyo by paying Japanese yen. Or euros can be acquired in Tokyo using Japanese yen, which can subsequently be sold in NYC to yield dollars. The first transaction, which is based on a direct yen for dollar exchange, can be termed as the natural rate. The second may be termed as the synthetic rate. To rule out arbitrage, the natural rate must be equal to the synthetic rate. If we assume that the Tokyo market is fairly priced, then the rate that must prevail in NYC to rule out arbitrage is

Now let us make matters more realistic by introducing bid–ask spreads. Consider the following rates in Tokyo.

- 124.25–125.50 EUR–JPY

- 111.75–112.50 USD–JPY

The issue is what should be the rates in NYC to rule out triangular arbitrage.

Let us depict the two rates as: Sb – Sa EUR–USD where the subscripts denote bid and ask respectively.

Consider an arbitrageur who borrows 1 MM USD and sells it in Tokyo to yield 111.75MM JPY. This can be used to acquire 111,750,000/125.50 = 890,438.25 euros in Tokyo. The euros can be sold in NYC to yield Sb × 890,438.25 USD. The condition to preclude arbitrage is therefore

Sb may be termed as the natural bid rate.

The no-arbitrage condition is that

Consider the RHS, which represents an indirect way of acquiring euros using US dollars, as it requires the acquisition of Japanese yen using dollars followed by the acquisition of euros using yen. Thus, it can be termed as a synthetic ask rate for euros in terms of USD. Hence the no-arbitrage condition is

In other words, the natural bid should be less than or equal to the synthetic ask.

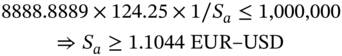

We can derive a similar condition for the natural ask. Take the case of a trader who borrows 1MM Yen and acquires dollars in Tokyo. He will get 1,000,000/112.50 = 8,888.8889 USD. This can be used to acquire 8,888.8889 × 1/Sa euros in NYC. The euros can be sold in Tokyo to yield 8888.8889 × 124.25 × 1/Sa Japanese yen. The no-arbitrage condition is that:

Thus, the no-arbitrage condition is that

The RHS represents an indirect way of acquiring US dollars using euros for it requires the acquisition of Japanese yen using euros followed by the acquisition of US dollars using yen. Thus, it can be termed as a synthetic bid rate for euros in terms of USD. Hence the no-arbitrage condition is

In other words, the natural ask should be greater than or equal to the synthetic bid. Of course, the natural ask must be greater than the natural bid.

CROSS RATES

As we have just seen, a bid for euros in terms of the dollar can be generated by multiplying the (EUR–JPY)bid by the (JPY–USD)bid. Similarly the ask for euros in terms of the dollar can be generated by multiplying the (EUR–JPY)ask by the (JPY–USD)ask. The bid and ask rates for a pair of currencies that are arrived at by using rates relative to a third currency are referred to as cross rates. In our illustration, the common currency was the Japanese yen, which was the base currency with respect to the USD and the variable currency with respect to the euro. Thus, in order to compute cross rates from two given quotes where the common currency is the base rate in one quotation and the variable currency in the other, we need to multiply the two quoted bid rates to arrive at the cross bid and multiply the two quoted ask rates to arrive at the cross ask.

Sometimes, however, the common currency may be either the base currency with respect to both the other currencies, or the variable currency with respect to both. In such cases, the cross rate may be generated using the following logic.

Assume that a bank in NYC is quoting the following rates.

- 1.2225–1.2295 EUR–USD

- 0.6225–0.6350 AUD–USD

In this case, the USD is the variable currency in both cases. Consider the synthetic (EUR–AUD)bid. It requires the trader to sell euros and buy USD and then sell USD to buy AUD. A dealer selling a euro will get 1.2225 USD. A dealer selling one USD will get 1/0.6350 AUD. Thus the synthetic (EUR–AUD)bid = 1.2225/0.6350 = 1.9252 = (EUR–USD)bid ÷ (AUD–USD)ask.

Now consider the synthetic ask. In order to buy euros, the trader can buy US dollars by selling Australian dollars and then sell the US dollars to acquire a euro. A trader selling an Australian dollar will get 0.6225 USD. The USD price for buying a euro is 1.2295. Thus, in order to buy a euro using Australian dollars, the trader requires 1.2295/0.6225 AUD or 1.9751 EUR–AUD. Therefore the synthetic (EUR–AUD)ask = (EUR–USD)ask ÷ (AUD–USD)bid. Thus, in order to arrive at a spot rate from two other rates which have a common variable currency, we need to divide opposite sides of the quotes. In this case, the synthetic EUR–AUD bid rate is obtained by dividing the EUR–USD bid rate by the AUD–USD ask rate. Similarly, the EUR–AUD ask rate is obtained by dividing the EUR–USD ask rate by the AUD–USD bid rate.

Now let us consider a situation where the common currency is the base currency in both cases. Assume that the following quotes are available.

- 0.8225–0.8375 USD–EUR

- 1.5225–1.5350 USD–AUD

Consider the synthetic EUR–AUD bid. A trader selling a euro will get 1/0.8375 USD. That can be sold to get 1.5225 × 1/0.8375 = 1.8179 AUD. Thus, the EUR–AUD bid is equal to the USD–AUD bid divided by the USD–EUR ask. Now consider the EUR–AUD ask rate. To buy a US dollar the trader requires 1.5350 AUD. With one USD the trader can acquire 0.8225 euros. Thus, to acquire one euro the trader requires 1.5350/0.8225 = 1.8663 AUD. Thus, the EUR–AUD ask rate is equal to the USD–AUD ask divided by the USD–EUR bid. Hence, once again, to arrive at a spot rate from two other rates that have a common base currency, we need to divide opposite sides of the quotes.

MARKET RATES AND EXCHANGE MARGINS

Market rates, or interbank rates, are rates that are confronted by foreign exchange dealers. When quoting rates to retail customers, the dealers will apply a margin. Thus the bid–ask spread for the dealer will be greater than the prevailing spread in the interbank market. Here is an illustration.

VALUE DATES

Spot market transactions have a value date of two business days after the trade date. For instance, if a spot transaction occurs on a Monday, the value date will be Wednesday. The market for the purchase and sale of foreign currencies with a delivery date that is more than two business days after the trade date is referred to as the forward market. The delivery dates for forward contracts, as is the case for money market transactions, are based on the modified following business day convention and the end-to-end rule.

For instance, assume that we are on 5 March 20XX, and that the spot value date is 7 March. A 1-month forward contract will have a value date of 7 April, while a 3-month forward contract will have a value date of 7 June. If the value date was a holiday, then the delivery would be moved to the next business day. As in the case of the money market, if moving the value date forward due to a market holiday were to result in a situation where it falls in the subsequent calendar month, then it would be moved back to the last business day of the same calendar month. For instance, assume that we are on 29 July 20XX. The spot value date is 31 July while the value date for a 1-month forward contract is 31 August. If 31 August were to be a Sunday, the value date for the contract will be 29 August.

As per the end-to-end rule, if the spot value date is the last business day of a month, then the forward value date will be the last business day of the corresponding month. For instance, if 31 July were to be the spot value date, then a 2-month forward contract will have a value date of 30 September.

THE FORWARD MARKET

In most foreign exchange markets the standard maturities for forward contracts are one week, two weeks, and one, two, three, six, nine, and 12 months. Countries like the United States have an active currency futures market. Foreign currencies, however, are one product where the volume of forward contract transactions is much higher than the trading volumes in futures markets.

If the forward rate for a maturity exceeds the spot rate, then we say that the foreign currency is trading at a premium. If the forward rate is less than the spot rate, however, then the foreign currency would be said to be trading at a discount. If the two rates were to be equal, then the currency would be said to be trading flat. Consider Example 8.6.

OUTRIGHT FORWARD RATES

Forward contracts that are undertaken in isolation are referred to as outright forward contracts, and the corresponding quotes are referred to as outright forward rates. An outright forward contract has a single leg. For instance, Bank ABC buys one million USD one month forward, or Bank XYZ sells one million euros three months forward. In practice in the interbank market, however, whenever a bank undertakes a forward contract it will be accompanied by a spot transaction in what is termed as a swap deal. We will examine swap deals in detail shortly. Unlike an outright forward contract, a swap has two legs.

Outright forward rates have the same properties as spot rates. For instance, if the 1-month rate for the euro is given as 1.2250–1.2325 EUR–USD, then the corresponding rates in terms of USD–EUR are 0.8114–0.8163 USD–EUR where the USD–EUR bid is the reciprocal of the EUR–USD ask and the USD–EUR ask is the reciprocal of the EUR–USD bid.

The rules for calculating cross rates are also the same. For instance, assume that on a given day the following rates are observed in the London market.

- 3-month Forward: 0.5000–0.5075 USD–GBP

- 3–month Forward: 0.7500–0.7560 EUR–GBP

The GBP is the variable currency in both cases.

The bid for a 3-month forward contract for euros in terms of the USD is given by 0.7500 ÷ 0.5075 = 1.4778 EUR–USD, while the ask rate may be computed as 0.7560 ÷ 0.5000 = 1.5120 EUR–USD.

SWAP POINTS

In practice, the forward rates are not quoted directly in the interbank market. Instead, the difference between the forward and spot rates, which is termed as the forward margin or swap points, is given, and the corresponding outright rates have to be deduced from the data.

Consider the following data.

- Spot: 0.5000–0.5075 USD–GBP

- 1-month Forward Points: 45/75

The numbers 45 and 75 represent the last two decimal places, or what we have termed as points. The swap points represent the difference between the forward rate and the corresponding spot rate. It has not been specified, however, whether the points should be added or subtracted in order to arrive at the outright forward rates. So, the issue is whether we add the numbers or subtract them.

It must be remembered that the spot market will have the lowest bid–ask spread and that as we negotiate contracts for future points in time, the spread will widen. This is because the relative liquidity in the spot market is the highest and the liquidity declines as we go forward in time.

In this case, if we add 45 points on the LHS and 75 points on the RHS, the spread will widen, whereas if we were to subtract the numbers the spread will narrow. Thus, a quote like 45/75 signifies that the foreign currency is at a forward premium and that the swap points need to be added. Hence the corresponding outright forward rates in this case are 0.5045–0.5150 USD–GBP.

Thus, if the swap points are given as Small Number/Large Number, it connotes that the foreign currency is at a forward premium and that consequently the points need to be added.

Now consider the following situation. On a given day in Frankfurt the rate for the US dollar is given as

- Spot: 0.8000–0.8075 USD–EUR

- 3-Month Swap Points: 95/55

In this case it is obvious that if the forward market were to have a higher spread than the spot market, then we need to subtract the corresponding points from the respective sides. Thus, the equivalent outright forward rates in this case are:

- 3-Month Forward: 0.7905–0.8020

Thus, the rule is that if the swap points are given as Large Number/Small Number, it connotes that the foreign currency is at a forward discount and consequently the points need to be subtracted.

If the swap points quote were to state par, then it indicates that the spot rate and the outright forward rates are identical. Sometimes the swap points may be specified as x–y A/P. A/P stands for around par. It signifies that the swap points on the LHS should be subtracted while those on the RHS should be added. Consider the following quote.

- Spot: 0.8000–0.8005 USD–EUR

- 1-Month Forward: 9/5 A/P

The corresponding outright rates for a 1-month forward contract are 0.7991–0.8010.

In the absence of the A/P specification, we would subtract 9 pips from the LHS and 5 pips from the RHS. The spread will widen by 4 points. In this case, however, we will subtract 9 pips from the LHS and add 5 pips on the RHS. Thus, the spread will widen by 14 points.

The logic we have used to derive the outright forward rates is valid in the case of direct quotes. In the case of indirect quotes, although the swap points have the same meaning, the treatment is different. Small Number/Large Number implies a foreign currency that is at a forward premium whether rates are quoted directly or indirectly. If the rates are quoted indirectly, however, then the swap points must be subtracted from the respective sides. Similarly, if the swap points are given as Large Number/Small Number, it indicates a foreign currency that is at a forward discount. But if the rates were to be quoted indirectly, then the numbers need to be added. Consider the following illustration.

BROKEN-DATED CONTRACTS

Most forward contracts are for standard time intervals, such as one month or three months. At times, however, a client may approach a dealer seeking a contract with a nonstandard maturity date, or a date that falls between two standard intervals. Such contracts are referred to as broken-dated contracts, and to compute the applicable rate for such odd periods, a method of linear interpolation is used.

COVERED INTEREST ARBITRAGE

We will now derive the relationship between the spot rate and the forward rate for a given maturity, using arbitrage arguments. We will denote the spot rates, forward rates, and interest rates using the following symbols. Subsequently we will illustrate our arguments with the help of a numerical example.

- Spot: Sb − Sa USD–EUR

- 3-Month Forward: Fb − Fa USD–EUR

- Borrowing/lending rates in Frankfurt (for euros): rdb − rdl

- Borrowing/lending rates in NYC (for dollars): rfb − rfl

Note: This is a direct quote for the US dollar in Frankfurt. Consequently, the rate for borrowing/lending euros is the domestic rate, while that for borrowing/lending dollars is the foreign rate.

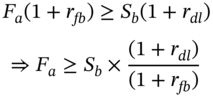

We will first consider cash-and-carry arbitrage. It entails the acquisition of one unit of the foreign currency and the simultaneous assumption of a short position in a forward contract to sell the foreign currency after three months. In order to buy a US dollar, the arbitrageur will have to borrow Sa EUR. This will be financed at a rate of rdb. This dollar can be invested at the rate rfl. This will yield (1 + rfl) USD at maturity, which can be sold forward at the outset at a rate Fb. At maturity the amount borrowed in euros will have to be repaid with interest which will entail an outflow of Sa(1 + rdb). Thus, to rule out arbitrage we require that

Now consider a reverse cash-and-carry strategy. It will require the arbitrageur to borrow one US dollar to acquire Sb euros. The amount that is borrowed in dollars will have to be financed at the rate rfb. The euros can be invested at the rate rdl. At the outset the arbitrageur will have to go long in a forward contract to buy (1 + rfb) dollars at the rate of Fa. To rule out arbitrage we require that

A PERFECT MARKET

In a perfect market there will be no bid–ask spreads in either the spot or the forward market, and the borrowing rate for both currencies will be equal to the corresponding lending rates. Thus, in such a scenario Sa = Sb = S and Fa = Fb = F. The borrowing/lending rate in Frankfurt will be rd while that in NYC will be rf. Thus, the no-arbitrage condition in such circumstances may be stated as

This is termed as the interest rate parity condition.

We will illustrate these principles with the help of a numerical example.

FOREIGN EXCHANGE SWAPS

It is a common practice for a bank to enter into a foreign exchange swap with a counterparty. Such a transaction entails the purchase or sale of a currency on the spot value date with a simultaneous agreement to sell or purchase the same currency at a future date. That is, it may involve a spot sale accompanied by a forward purchase or a spot purchase accompanied by a forward sale. In some cases, the transaction may entail a purchase/sale for a future date accompanied by a sale/purchase for a longer maturity. These transactions are referred to as forward to forward swaps.

In such transactions the key variable is the forward margin or swap points for the foreign currency. The rate for the spot leg per se is irrelevant and in practice the spot purchase or sale may be done at the prevailing bid, or the prevailing ask, or at a rate that is in between. The mechanics of such transactions may be illustrated with the help of a numerical example.

THE COST

The cost of a foreign exchange swap is a function of the interest rate differential between the two currencies and is defined as the foreign exchange value of the interest rate differential between the currencies for the maturity of the swap. The party who holds the currency that pays a higher interest rate will effectively pay the counterparty, thereby neutralizing the rate differential and equalizing the returns on the two currencies.

Assume that covered interest arbitrage holds and for ease of exposition ignore bid–ask spreads and differential borrowing and lending rates. From the interest rate parity condition, we know that

Thus

THE MOTIVE

What could be the motivation for a swap such as the one undertaken by BNP Paribas with Bank of America? In practice, while banks regularly execute outright forward contracts with their nonbank clients, most interbank transactions entailing the use of forward contracts are done in the form of a foreign exchange swap.

Assume that Bank of America has executed a forward contract with a client to buy 1MM euros six months later. It will thus have a long position in euros six months forward. If the bank were to desire to square off this position, it will have to sell 1 MM euros six months forward. It may not always be easy, however, to locate a counterparty with matching opposite needs, with whom an offsetting outright forward contract can be executed. It is easier in practice to do a swap. In this case the swap will require Bank of America to buy euros spot, and sell the currency six months forward. This creates the required offsetting short forward positions in euros. In the process, however, the bank has created a long spot position in euros. This can be easily offset by selling the euros in the interbank market.1

A second reason why banks prefer to do foreign exchange swaps rather than an outright forward is that although an outright forward is influenced by both the spot rate and the difference in the interest rates for the two currencies, a foreign exchange swap is primarily influenced by the interest rate differential. Thus, an outright forward transaction has the effect of combining two related but different markets in a single transaction, which may not be acceptable to the bank, as compared to a swap, which is primarily an interest rate instrument.2 Speculators do not like financial products where multiple economic variables are intertwined. Consequently, speculators in the foreign exchange market prefer FX swaps to outright forward contracts.

INTERPRETATION OF THE SWAP POINTS

Consider the following quote in the foreign exchange market in NYC on a given day.

- Spot: 1.2500–1.2625 EUR–USD

- 1-Month Forward: 50/90

The first figure (the swap points on the left) represents a transaction where the quoting bank is selling the base currency spot and is buying it back one month forward. In this illustration the quoting bank is prepared to offer a premium of 50 points. The second figure (the swap points on the right) represents a transaction where the quoting bank is buying the base currency spot and selling the same one-month forward. In this illustration the quoting bank is charging a premium of 90 points. If we term the spot transaction as the near-date transaction and the forward contract as the far-date transaction, the swap points on the left are for a transaction that entails the sale of the base currency on the near-date and its acquisition on the far-date, while the swap points on the right are for a transaction that entails the purchase of the base currency on the near-date and its subsequent sale on the far-date.3 This statement should of course be perceived from the standpoint of the quoting bank.

A CLARIFICATION

There is a derivative product known as a currency swap. It requires two parties to swap interest rate payments in the two chosen currencies periodically, based on prespecified benchmarks. The principal amounts on the basis of which the interest flows are calculated are always exchanged at the end of the swap; however, there may or may not be an exchange of principal at inception. Here is an illustration.

SHORT-DATE CONTRACTS

A short date transaction may be defined as one for which the value date is before the spot value date. There are two possibilities, value today and value tomorrow, where tomorrow refers to the next business day. In the foreign exchange markets, three types of one-day swaps are quoted. These are:

- Between today and tomorrow: Referred to as Overnight or O/N

- Between tomorrow and the next day: Referred to as tom/next or T/N

- Between the spot date and the next day: Referred to as spot/next or S/N

Let us first consider a value tomorrow transaction. An outright sale for a bank, with value tomorrow, may be viewed as a combination of the following transactions: spot sale of euros, accompanied by a swap that includes sale of euros for tomorrow, accompanied by a spot purchase of euros.

Let us assume that the tom/next swap points are given as 25/15. The question is, how do we deal with these points? That is, do we deal with them in the same way as we do for normal forward contracts or is there a difference? Before we proceed, let us reconsider a 1-month forward contract from the standpoint of the quoting bank.

An outright sale one month forward may be viewed as a spot sale accompanied by a swap that entails the spot purchase and forward sale of the base currency. Assume that the swap points are given as a/b. The first number represents a transaction for selling spot and buying forward, while the second number represents a transaction for buying spot and selling forward. Thus, if a < b, it implies that the foreign currency is at a forward premium, and we will add the numbers to the respective sides. The rationale here is that if the currency is at a forward premium, the premium that the bank will offer when it buys forward will be less than what it will charge when it sells forward. On the other hand, if a > b, it implies that the foreign currency is a forward discount, and we should subtract the numbers from the respective sides. The rationale is that if the currency is at a forward discount, then the discount that the bank will apply when it buys will be larger than what it will offer when it sells. As explained earlier, the swap points on the left are for selling the base currency on the near date and buying it on the far date, whereas the points on the right are for buying the base currency on the near date and selling it on the far date.

Now consider a value tomorrow sale transaction. As we have seen, it may be viewed as a combination of the spot sale of euros accompanied by a swap which entails the spot purchase of euros with the sale of euros for tomorrow. The difference between this swap and the swap corresponding to a 1-month outright forward sale is that this transaction is for the purchase of euros on the far date, whereas in the earlier case it was for the sale of euros on the far date. Thus, in this case, if the swap points are given as a/b, then the points applicable for an outright sale with value tomorrow are the points on the left side, while those applicable for an outright purchase are those on the right side. Remember that the transaction scheduled for tomorrow is the near-date leg while the spot transaction represents the far-date leg.

Now consider a number like 25/15. The implications are that when the bank is buying for value tomorrow it will give a premium of 15 points, whereas when it is selling for value tomorrow it will charge a premium of 25 points. The numbers cannot represent a discount because the bank will not offer a larger discount when it sells as compared to what it levies when it buys. On the other hand, what if the points had been given as 15/20? Clearly, this implies that the bank will apply a discount of 20 points when it buys euros for value tomorrow, while for sale transactions with value tomorrow it will offer a discount of only 15 points.

As can be surmised from the preceding arguments, the way to deal with the swap points in this case is to reverse them and then proceed as before. That is, for a value tomorrow transaction, if the tom/next swap points are given as a/b, we first invert them to obtain b/a. Then if it connotes a smaller number followed by a larger number, we will add the points to the respective sides. If it is a larger number followed by a smaller number, however, we subtract the points from the respective sides. As Steiner points out, the inversion of the swap points is purely from the standpoint of computation. The swap points themselves will not be quoted after inversion.

Now let us consider the procedure for arriving at a quote for a value today sale transaction. This can be viewed as a combination of three transactions.

- Sale of euros spot.

- A swap entailing a sale of euros for value tomorrow accompanied by a spot purchase of euros.

- A swap entailing a sale of euros for value today accompanied by a purchase of euros for value tomorrow.

The computation of the outright value today rates may be best illustrated with the help of an example.

Swap points for short-duration transactions like O/N or T/N, may be very small in practice. Often, they may be less than a point and will in practice be expressed either in fractions or as decimals. For instance, consider the following quote for an O/N swap.

It implies a quote of 2.25/1.75 points. At times the quote may be expressed directly in decimals, that is, as 2.25/1.75. In either case care should be exercised when they are being added to or subtracted from the spot rates.

OPTION FORWARDS

Clients negotiating a forward contract may be uncertain at times about the exact date on which they will have to pay or receive the foreign currency. In such cases, they have the freedom to negotiate a forward contract with the flexibility to transact within a specified time period. For instance, exporters based in Philadelphia may be of the opinion that they will receive a payment in euros sometime between two to three months from the date of negotiation of the forward contract. In such a situation they can negotiate a forward contract with an option to complete the contract on any date during the stated period. The option writer in such cases is the foreign exchange dealer, typically a bank. Dealers will quote a rate for the option forward based on what works out best for them. The implications of this would depend on whether the dealers are buying or selling the foreign currency and on whether the currency is quoting at a premium or a discount. We will illustrate various situations with the help of the following examples.

NONDELIVERABLE FORWARDS

A traditional forward contract entails the acquisition of a foreign currency if a long position is taken, or the delivery of a foreign currency if a short position is taken. In the case of a nondeliverable forward contract there is no need to acquire or deliver a foreign currency. Instead, the two parties simply settle the profit or loss with respect to the prevailing spot rate two business days before the maturity date of the forward contract.

Nondeliverable forwards can be offset prior to maturity. In this case, the profit/loss may be received/paid either at the original date of maturity of the contract or on the day of offsetting.

RANGE FORWARDS

These contracts impose a cap and a floor on the exchange rate. If the spot rate at maturity is higher than the cap, then the rate is set equivalent to it. If the spot rate at maturity is lower than the floor, however, then the applicable rate is the floor. If the spot rate is in between the two bounds, then the applicable rate is the prevailing spot rate.

For instance, assume a party buys a range forward with an upper limit of 0.8225 USD–EUR and a lower limit of 0.8075 USD–EUR. If the rate at maturity is 0.8275 USD–EUR, then the applicable rate will be 0.8225. If the rate at maturity is 0.8025 USD–EUR, however, then the applicable rate is 0.8075. If the terminal spot rate is 0.8185 USD–EUR, then it will be the applicable rate.

FUTURES MARKETS

FOREX futures trading is active on the CME Group. The exchange currently offers futures contracts on a variety of currencies, including the euro, the British pound, and the Japanese yen.

HEDGING USING CURRENCY FUTURES

Futures contracts on foreign currencies may be used by traders to hedge their risks in the spot market. A party who knows that it will be selling a foreign currency in the future will be worried that the currency may depreciate or, in other words, that the price of the currency in terms of the domestic currency may fall. Consequently, it will hedge by going short in futures contracts.

On the other hand, a party that knows it will be acquiring a foreign currency in the future will be concerned that the currency may appreciate, which would mean that the price of that currency in terms of the domestic currency may rise. Such parties will seek to hedge by going long in futures contracts.

We will illustrate buying and selling hedges with the help of numerical examples.

A SELLING HEDGE

A BUYING HEDGE

EXCHANGE-TRADED FOREIGN CURRENCY OPTIONS

NASDAQ OMX PHLX offers options contracts on a number of foreign currencies, with settlement in US dollars. Option premiums are quoted in points where one point is equivalent to $100. For instance, on 15 September 20XX, the Canadian dollar was quoting at 0.8700 CAD–USD. A call options contract with a strike price of 80 cents was quoting at 9.25. Thus, the premium for the contract was 925 USD.

SPECULATING WITH FOREX OPTIONS

A foreign exchange option gives the holder the right to buy or sell a currency. As is the case with other underlying assets, the option may be a call or a put, and both European and American-style options are possible. The number of units of the currency that can be bought or sold per contract will be specified, and both the exercise price and the option premium will be stated in terms of the number of units of the other currency.

The Garman-Kohlhagen Model

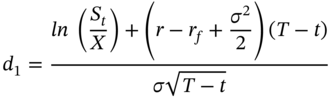

This is a variation of the Black-Scholes model that was developed to price European options on foreign currencies. In addition to the usual parameters required to calculate an option premium using the Black-Scholes model, the Garman-Kohlhagen model requires us to specify the riskless rate of interest in the foreign country, rf. As per the model, the price of a European call option is given by

where

and ![]() .

.

The price of a European put is given by

In Example 8.29 we will demonstrate the computation of option premiums for the euro, using the Garman-Kohlhagen model.

Put-Call Parity

The put-call parity relationship for foreign currency options may be expressed as

The Binomial Model

The binomial model can be used to value options on foreign currencies. The only difference is with respect to the definition of the risk-neutral probability p. For currency options, the probability is defined as

In Example 8.30 we will demonstrate the computation of option premiums for the euro, using the binomial model.

EXCHANGE RATES AND COMPETITIVENESS

If a currency appreciates, the importers in the home country stand to benefit, whereas if it depreciates, exporters in the home country stand to benefit. Despite a currency movement in their favor, however, producers and consumers may be adversely hit due to a more beneficial currency movement for a competitor in a different country. Here is an illustration.

The euro is quoting in Mumbai at 90.0000 EUR–INR and in Singapore at 1.8000 EUR–SGD. The rupee-Singapore dollar rate is 50.0000 SGD–INR.

A company in India sells a product at 140 euros in Germany. The cost of production in India is 9,000 rupees. Thus, the margin in euros is 40. A company in Singapore sells an identical product for the same price in the EU. Its cost of production is 180 SGD. Thus, it too has a margin of 40 euros.

Now assume that the Indian rupee depreciates to 96.00 EUR–INR, while the Singapore dollar depreciates to 2.00 EUR–SGD. The price of the product remains at 140 euros.

The cost of production in euros for the Indian company is 93.75 euros. Thus, the margin is 46.25 euros. The currency movement has benefited the Indian company.

The cost of production for the Singaporean company is 90.00 euros. Its margin is 50.00 euros. The currency movement is beneficial in this case as well.

Although both companies have benefited from exchange rate movements, the margin for the Singaporean company is greater after the change in the exchange rate. Hence, it can cut its selling price by a greater amount as compared to its Indian competitor, and can potentially increase its market share.