CHAPTER 10

Swaps

INTRODUCTION

What exactly is a swap transaction? As the name suggests, it entails the exchanging or swapping of cash flows between two counterparties. There are two broad categories of swaps: interest rate swaps and currency swaps.

In the case of an interest rate swap, all payments are denominated in the same currency. Obviously, the two cash flows being exchanged will be calculated using different interest rates. For instance, one party may compute its payable using a fixed rate of interest, while the other may calculate what it owes based on a market benchmark such as LIBOR. Such interest rate swaps are referred to as fixed-floating swaps. A second possibility is that both payments may be based on variable or floating rates. For instance, the first party may compute its payable based on LIBOR while the counterparty may calculate what it owes based on the rate for a Treasury security. Such a swap is referred to as a floating-floating swap. It should be obvious to the reader that we cannot have a fixed-fixed swap in practice. For example, consider a deal where Bank ABC agrees to make a payment to the counterparty every six months on a given principal, at the rate of 5.25% per annum in return for a counterpayment based on the same principal that is computed at a rate of 6% per annum. Clearly, this is an arbitrage opportunity for Bank ABC, because what it owes every period will always be less than what is owed to it. No rational counterparty will therefore agree to such a contract. Thus, in the case of an interest rate swap, prior to the exchange of interest on a scheduled payment date, there must be a positive probability of a net payment being received for both the parties to the deal.

In the case of an interest rate swap, a principal amount needs to be specified to facilitate the computation of interest. There is no need, however, to physically exchange this principal at the outset. Therefore, the underlying principal amount in such transactions is referred to as a notional principal.

Now let us consider a currency swap. Such a contract also entails the payment of interest by two counterparties to each other, the difference being that the payments are denominated in two different currencies. Because there are two currencies involved there are three interest computation methods possible: fixed-fixed, fixed-floating, and floating-floating.

In Example 10.1 we illustrate the mechanics of a fixed-floating interest rate swap.

MARKET TERMINOLOGY

Let us first consider interest rate swaps. As we discussed, there are two possible counterpayments: fixed-floating and floating-floating. A swap where one of the rates is fixed is referred to as a coupon swap. On the other hand, a swap wherein both the parties are required to make payments based on varying rates is referred to as a basis swap. Thus, the IRS that we considered earlier, where Bank Exotica was required to pay at a fixed rate of 6.40% per annum in exchange for a payment from Bank Halifax that was based on LIBOR, is an example of a coupon swap.

In a coupon swap, the party which agrees to make payments based on a fixed rate is referred to as the payer, whereas the counterparty, which is committed to making payments on a floating-rate basis, is referred to as the receiver.1 These terms cannot be used in the case of basis swaps, however, because both the cash flow streams are based on floating rates. In practice it is important to be explicit in order to avoid ambiguities. Thus, for each counterparty, both the rate on the basis of which it is scheduled to make payments and the rate on the basis of which it is scheduled to receive payments should be explicitly stated. For instance, in the case of the interest rate swap that we considered earlier, the terms would be stated somewhat as follows.

- Counterparties: Bank Exotica and Bank Halifax

- Interest Rate-1: A fixed rate of 6.40% to be paid by Bank Exotica to Bank Halifax.

- Interest Rate-2: A variable rate based on the 6-month LIBOR prevailing at the onset of the corresponding six-monthly period, to be paid by Bank Halifax to Bank Exotica.

KEY DATES

There are four important dates for a swap. Consider the two-year swap between Bank Exotica and Bank Halifax. Assume that the swap was negotiated on 10 June 20XX with a specification that the first payments would be for a six-month period commencing on 15 June 20XX; 10 June will be referred to as the transaction date. The date from which the interest counterpayments start to accrue is termed as the effective date. In our illustration the effective date is 15 June.

Our swap by assumption has a tenor of two years and consequently the last exchange of payments will take place on 15 June 20(XX+2). This date will consequently be referred to as the maturity date of the swap. We will assume that the four exchanges of cash flows will occur on 15 December 20XX, 15 June 20(XX+1), 15 December 20(XX+1), and 15 June 20(XX+2). The first three dates, on which the floating rate will be reset for the next six-monthly period, are referred to as reset or refixing dates.

INHERENT RISK

An interest swap exposes both parties to interest rate risk. Let us consider the fixed-floating swap between Bank Exotica and Bank Halifax. For the fixed-rate payer, the risk is that the LIBOR may decline after the swap is entered into. If so, while the payments to be made by it would remain unchanged, its receipts will decline in magnitude. From the standpoint of the floating-rate payer, the risk is that the benchmark, in this case the LIBOR, may increase after the swap is agreed upon. If so, while its receipts would remain unchanged, its payables will increase. A priori we cannot be sure as to whether LIBOR will increase or decline. Consequently, ex ante both the parties to the contract are exposed to interest rate risk.

THE SWAP RATE

What exactly is the swap rate? The term refers to the fixed rate of interest that is applicable in a coupon swap. There are two conventions for quoting the interest rate. The first practice is to quote the full rate in percentage terms. This is referred to as an all-in price. In certain interbank markets, however, the practice is to quote the fixed rate as a difference or spread, in basis points, between the fixed rate and a benchmark interest rate. The benchmark that is used is the yield for a government security with a time to maturity equal to the tenor of the swap. The two methods can be best described with the help of an illustration.

TABLE 10.4 Bid–Ask Quotes for Euro-denominated IRS

| Tenor | Bid | Ask |

|---|---|---|

| 1-Year | 1.50% | 1.55% |

| 2-Year | 1.70% | 1.75% |

| 3-Year | 1.90% | 1.95% |

| 5-Year | 2.25% | 2.30% |

| 10-Year | 2.90% | 2.95% |

| 15-Year | 3.25% | 3.30% |

| 25-Year | 3.20% | 3.25% |

ILLUSTRATIVE SWAP RATES

Consider the hypothetical quotes for euro-denominated interest rate swaps on a given day, as shown in Table 10.4. Assume that the corresponding floating rate is the six-month Euribor.

Such a rate schedule, which is typically provided by a professional swap dealer, may be interpreted as follows. A swap dealer will give a two-way quote wherein the bid is the fixed rate at which he is willing to do a swap that requires him to pay the fixed rate. Obviously the ask represents the rate at which he will do a swap that requires him to receive the fixed rate. Quite obviously the spread must be positive.

DETERMINING THE SWAP RATE

Let us reconsider the coupon swap between Bank Exotica and Bank Halifax. The swap rate was arbitrarily assumed to be 6.40%. We will now demonstrate as to how this rate will be set in practice.

To understand the pricing of swaps, consider an alternative financial arrangement where Bank Exotica issues a fixed-rate bond with a principal of 2,500,000 US dollars and uses the proceeds to acquire a floating-rate bond with the same principal. Assume that the benchmark for the floating-rate bond is the 6-month LIBOR, and that both bonds pay coupons on a semiannual basis. The initial cash flow is zero because the proceeds of the fixed-rate issue will be just adequate to purchase the floating-rate security. Every six months the bank will receive a floating rate of interest based on the 6-month LIBOR on a principal amount of $2,500,000 and will have to make an interest payment for the same principal, based on a fixed rate of interest. When the two bonds mature, the amount received when the bank redeems the principal on the floating-rate bond held by it will be just adequate for it to repay the principal on the bond issued by it. The net cash flow at maturity is therefore zero. Thus, structurally this financial arrangement corresponds to an interest rate swap with a notional principal of $2,500,000 wherein the bank pays a fixed rate of interest every six months in return for an interest stream that is based on the 6-month LIBOR. To ensure that the combination of the two bonds exactly matches the structure of the swap, we need to assume that the bonds also pay coupons based on the same day-count convention, which in this case has been assumed to be 30/360.

TABLE 10.5 Observed Term Structure

| Time to Maturity | Interest Rate per Annum |

|---|---|

| 6-months | 5.25% |

| 12-months | 5.40% |

| 18-months | 5.75% |

| 24-months | 6.00% |

We will now demonstrate how the fixed rate of a coupon swap can be determined. Let us assume that the term structure for LIBOR is as shown in Table 10.5.

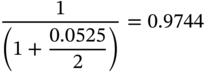

These interest rates need to be converted to discount factors, which can be done as follows.2 The discount factor for the first payment (after six months) is

The remaining discount factors may be computed as follows.

Because we are at the start of a coupon period, the price of the floating-rate bond should be equal to the principal value of $2,500,000. The issue is, therefore, what is the coupon rate that will make the fixed-rate bond have the same value at the outset? Let us denote the annual coupon in dollars by C.

Thus, we require that

This obviously implies that the coupon rate is

TABLE 10.6 Discount Factors as per Market Convention

| Time to Maturity | Discount Factor |

|---|---|

| 6-months | 0.9744 |

| 12-months | 0.9488 |

| 18-months | 0.9206 |

| 24-months | 0.8929 |

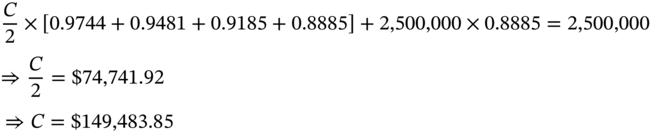

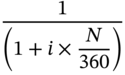

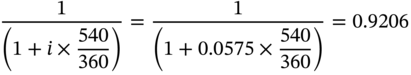

THE MARKET METHOD

The convention in the LIBOR market is that if the number of days for which the rate is quoted is N, then the corresponding discount factor is given by

For instance, consider the 18-month rate of 5.75%. The corresponding discount factor is

The vector of discount factors for our example is shown in Table 10.6.

The corresponding swap rate is 5.7323%.

VALUATION OF A SWAP DURING ITS LIFE

Let us consider the swap between Bank Exotica and Bank Halifax. Assume that two months have elapsed since the swap was entered into, and that the current term structure of interest rates is as given in Table 10.7. We have used the market method for computing the discount factors.

TABLE 10.7 The Term Structure of Interest Rate After Two Months

| Time to Maturity | Interest Rate per annum | Discount Factor |

|---|---|---|

| 4-months | 5.50% | 0.9820 |

| 10-months | 5.80% | 0.9539 |

| 16-months | 6.05% | 0.9254 |

| 22-months | 6.25% | 0.8972 |

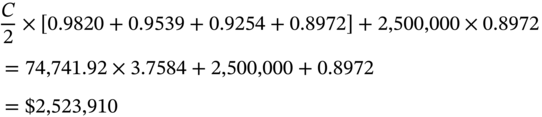

The value of the fixed-rate bond can be obtained using the following equation.

The value of the floating-rate bond may be computed as follows. The next coupon is known for it would have been set at time zero, that is, two months prior to the date of valuation. The magnitude of this coupon is

Once this coupon is paid, the value of the bond will revert back to its face value of 2,500,000. Thus, the value of this bond after four months will be $2,565,625. Consequently, its value today is:

From the standpoint of the fixed-rate payer, the swap is equivalent to a long position in a floating-rate bond that is combined with a short position in a fixed-rate bond. Thus, the value of the swap for the fixed-rate payer is:

That is, because the value of the fixed-rate liability is higher than that of the floating-rate asset, the value of the swap for Bank Exotica, the fixed-rate payer, is negative. What this implies is that if the bank were to seek a cancellation of the original swap, with the consent of the counterparty of course, it would have to pay $4,466 to the counterparty.

From the standpoint of the counterparty, the value of the swap is $4,466. Thus, in the event of cancellation of the contract it will get a cash flow of this magnitude from Bank Exotica.

TERMINATING A SWAP

As we have just seen, one way to exit from an existing swap contract is by having it canceled with the approval of the counterparty. This will entail an inflow or outflow of the value of the swap depending on how interest rates have moved since the last periodic cash flow was exchanged. In market parlance this is known as a buyback or close-out. In our illustration, Bank Exotica would have to pay $4,466 to Bank Halifax to close out the contract. In practice Bank Exotica will have the option of selling the swap to a party other than Bank Halifax, which is the original counterparty. This would of course require the approval of Bank Halifax. In this case as well, the party who buys the swap from the bank will expect to be paid the value of the swap, which is $4,466 in this case.

Another way for Bank Exotica to exit from its commitment would be to do an opposite swap with a third party. That is, it would have to do a 22-month swap with a party wherein it pays LIBOR and receives the fixed rate. This is known as a reversal.

It must be remembered that if it were to do so, there would be two swaps in existence. So, Bank Exotica would be exposed to credit risk from the standpoint of both counterparties.

THE ROLE OF BANKS IN THE SWAP MARKET

In the early years, when the swap market was evolving, it was a standard practice for banks to play the role of an intermediary. That is, they would bring together two counterparties in return for what was termed as an arrangement fee. As the market has evolved, such arrangement fees have become extremely rare, except perhaps for contracts which are very exotic or unusual.

These days most banks will don the mantle of a principal party. The reasons why they are required to do so are twofold. The first is that nonbank counterparties are reluctant to reveal their identity when entering into such deals. Consequently, they are more comfortable dealing with a bank while negotiating such contracts. The second reason is that for most parties to such transactions it is easier to evaluate the credit risk while dealing with a bank than while negotiating with a nonbank counterparty. And, as we have seen, swaps being OTC transactions always carry an element of counterparty risk.

In the days when the market was in its infancy, banks would primarily do reversals. That is, they would, for instance, do a fixed-floating deal with a party only if they were hopeful of immediately concluding a floating-fixed deal for the same tenor with a third party. Parties that carry equal and offsetting swaps in their books are said to be running a matched book. As we have seen earlier, such parties are exposed to default risk from both the counterparties. These days banks are less finicky about maintaining such a matched position, and in most cases are willing to take on the inherent exposure for the period until they can eventually locate a party for an offsetting transaction.

MOTIVATION FOR THE SWAP

A party to a swap may enter into the contract with a speculative motive or with an incentive to hedge. Such transactions may also be used to undertake what is known as credit arbitrage arising due to the comparative advantage enjoyed by the participating institutions. We will analyze each of these potential uses.

Speculation

Morgan Bank and Brown Brothers Bank are both players in the US capital market, but with different expectations as to where interest rates are headed. Morgan is of the view that rates are likely to steadily decline over the next two years, while Brown Brothers is of the opinion that rates are likely to rise steadily over the same period. Assume that they enter into a coupon swap with a tenor of 2 years wherein Morgan agrees to pay interest at LIBOR every three months on a notional principal of $100MM, while Brown Brothers agrees to pay interest on the same notional principal and with the same frequency, but at a fixed rate of z% per annum.

Quite obviously both parties are speculating on the interest rate. If Morgan is right and rates do decline as it anticipates, Morgan's floating-rate payments are likely to be lower than its fixed-rate receipts, thereby leading to net cash inflows. If Brown Brothers is correct, however, and rates rise steadily as anticipated, its floating-rate receipts are likely to be in excess of its fixed-rate payments, thereby leading to net cash inflows. Because both parties are speculating, ex post one will stand vindicated while the other will have to countenance a loss.

Hedging

Swaps can be used as a hedge against anticipated interest rate movements. Donutz, a company based in Detroit, has taken a loan from First National Bank at a rate of LIBOR + 75 b.p. The company is worried that rates are going to increase and seeks to hedge by converting its liability into an effective fixed-rate loan. One way to do so in practice would be to renegotiate the loan and have it converted to a loan carrying a fixed rate of interest. This may not, however, be easy in real life. There will be a lot of administrative and legal issues and related costs. Consequently, it may be easier in practice for the company to negotiate a coupon swap wherein it pays fixed and receives LIBOR.

Assume that Morgan Bank agrees to enter into a swap with Donutz wherein it will pay LIBOR in return for a fixed interest stream based on a rate of 5.75% per annum.

The net result from the standpoint of Donutz may be analyzed as follows.

- Outflow-1 (Interest on the original loan): LIBOR + 75b.p.

- Inflow-1 (Receipt from Morgan Bank): LIBOR

- Outflow-2 (Payment to Morgan Bank): 5.75%

- Net Outflow: 5.75% + 0.75% = 6.50% per annum

Thus, the company has converted its loan to an effective fixed-rate liability carrying interest at the rate of 6.50% per annum.

COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE AND CREDIT ARBITRAGE

At times there are situations where, despite being at a disadvantage from the standpoint of interest payments with respect to another party, a party in the market for fixed-rate and variable-rate debt may still enjoy a comparative advantage in one of the two.

For instance, assume that Infosys, a software company based in San Jose, can borrow at a fixed rate of 7.50% per annum and at a variable rate of LIBOR + 125 b.p. IBM is in a position to borrow at a fixed rate of 6% per annum and a variable rate of LIBOR + 60 b.p. Thus, Infosys has to pay 150 b.p more as compared to IBM if it borrows at a fixed rate, but only 65 basis points more if it borrows at a floating rate. We say that although IBM enjoys an absolute advantage from the standpoint of borrowing in terms of both fixed-rate and floating-rate debt, Infosys has a comparative advantage if it borrows on a floating-rate basis.

Assume that Infosys wants to borrow at a fixed rate while IBM would like to borrow at a floating rate. It can be demonstrated that an interest rate swap can be used to lower the effective borrowing costs for both parties, as compared to what they would have had to pay in the absence of it.

Let us assume that IBM borrows 10MM dollars at a fixed rate of 6% per annum, while Infosys borrows the same amount at LIBOR + 125 b.p. The two parties can then enter into a swap wherein Infosys agrees to pay interest on a notional principal of 10MM at the rate of 5.75% per annum in exchange for a payment based on LIBOR from IBM. The effective interest rate for the two parties may be computed as follows.

- IBM: 6% + LIBOR − 5.75% = LIBOR + 25 b.p.

- Infosys: LIBOR + 125 b.p, + 5.75% − LIBOR = 7.00%

Thus, IBM has a saving of 35 basis points on the floating-rate debt whereas Infosys has a saving of 50 b.p on the fixed-rate debt. What exactly does this cumulative saving of 85 basis points represent? IBM has an advantage of 1.50% in the market for fixed-rate debt and 65 basis points in the market for floating-rate debt. The difference of 85 basis points manifests itself as the savings for both parties considered together.

Now let us introduce a bank into the picture. Assume that IBM borrows at a rate of 6% per annum and enters into a swap with First National Bank wherein it has to pay LIBOR in return for a fixed-rate stream based on a rate of 5.65%. Infosys, on the other hand, borrows at LIBOR + 125 b.p and enters into a swap with the same bank wherein it receives LIBOR in return for payment of 5.85%.

The net result of the transaction may be summarized as follows.

- IBM: Effective interest paid = 6% + LIBOR – 5.65% = LIBOR + 35 b.p.

- Infosys: Effective interest paid = LIBOR + 125 b.p. + 5.85% – LIBOR = 7.10%

- First National Bank: Profit from the transaction = LIBOR – 5.65% – LIBOR + 5.85% = 20 b.p.

The difference in this case is that the comparative advantage of 85 basis points has been split three ways. IBM saves 25 basis points, Infosys saves 40 basis points, and the bank makes a profit of 20 basis points.

It must be pointed out that the transaction that entails a role for the bank is more realistic in practice, as opposed to a deal where the two companies identify and directly enter into a swap with each other.

SWAP QUOTATIONS

The swap rate in the market can be quoted in four different ways.3 First, there are two possibilities with respect to the interest payments, that is, they may be either on an annual basis or on a semiannual basis. The second issue is that payments may be settled either on a money market or on a bond market basis, the difference being that the first convention is based on a 360-day year and an Actual/360 day-count convention, while the second is based on a 365-day year and an Actual/365 day-count convention.

Quotes on a semiannual basis can be converted to equivalent values on an annual basis and vice versa. The following examples illustrate the required procedures.

MATCHED PAYMENTS

Numero Uno Corporation has issued bonds carrying a coupon of 6.25% per annum, and it is of the opinion that market rates could decline. Consequently, it wishes to undertake a swap wherein it has to pay floating and receive fixed. Assume that the bonds pay interest on a semiannual basis and that the swap too entails six-monthly exchange of cash flows. The principal of the bonds is assumed to be 10MM as is the notional principal of the swap.

We will assume that Bank Deux is willing to arrange a swap that is suitable for Numero Uno, but with a swap rate of 5.80% per annum. The company, however, wants a fixed payment of $312,500 to match the cash outflow on account of the bonds issued by it. In practice, Bank Deux would accommodate the request as follows. Because Numero Uno wants to receive a higher fixed payment, as compared to what it would ordinarily have received, it must compensate the bank in the form of a positive spread with respect to the floating-rate payment that it is required to make. In this case, the difference in the fixed-rate payments is $45,000 per annum, which corresponds to 45 basis points. Thus, the bank will require Numero Uno to make a payment based on a rate of LIBOR + 45 basis points while making the floating counterpayment every six months.

AMORTIZING SWAPS

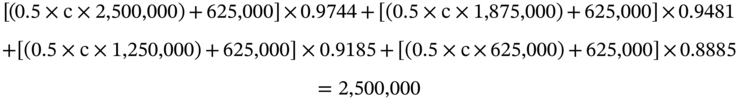

Unlike a plain-vanilla interest rate swap where the notional principal remains fixed for the life of the swap, in the case of an amortizing swap the principal steadily declines. Let's revisit the data in Table 10.5. We had assumed that the notional principal was $2,500,000. Assume the notional principal declines by $625,000 at the end of every six months. The fixed rate may be determined as follows.

The fixed rate comes out to be 5.71% per annum.

EXTENDABLE AND CANCELABLE SWAPS

An extendable swap confers the right to extend the maturity of the swap to one of the two counterparties in a swap. Usually, this right is given to the party paying the fixed rate of interest. Obviously, the party paying the fixed rate will exercise this option in a rising interest rate environment. In such a situation, while this party will continue to pay a fixed rate, the counterpayments it received will steadily increase. Because this party holds an option, it must pay for it. Consequently, the fixed rate in the case of such swaps will be higher than the rate in the case of plain-vanilla interest rate swaps.

A cancelable swap gives one of the counterparties the right to terminate the swap prematurely. If the right is given to the fixed-rate payer, it is called a callable swap, whereas if it is given to the floating-rate payer, it is called a putable swap. A callable swap will be terminated by the fixed-rate payer if rates are expected to decline, whereas a putable swap will be terminated by the fixed-rate receiver if rates are expected to increase. Consequently, the fixed rate for a callable swap will be higher than that of a plain-vanilla swap, whereas the fixed rate for a putable swap will be lower that of a plain-vanilla swap.

SWAPTIONS

A swaption represents an option on a swap. A payer swaption gives the holder the right to enter into a coupon swap as a fixed-rate payer. On the other hand, a receiver swaption gives the holder the right to enter into a coupon swap as a fixed-rate receiver.

The buyer of a swaption has to pay a premium to the writer. The exercise price for such derivatives is an interest rate. A payer swaption will be exercised only if the prevailing swap rate is higher than the exercise price; however, a receiver swaption will be exercised only if the prevailing swap rate is lower than the exercise price. A swaption may be of a European or an American variety.

CURRENCY SWAPS

A currency swap is like an interest rate swap in the sense that it requires two counterparties to commit themselves to the exchange of cash flows at prespecified intervals. The difference in this case is that the two cash flow streams are denominated in two different currencies. The two counterparties also agree to exchange at the end of the stated time period, or the maturity date of the swap, the corresponding principal amounts computed at an exchange rate that is fixed right at the outset.4

As we mentioned earlier, because the counterpayments are denominated in two different currencies, there are three possibilities from the standpoint of interest computation. That is, these swaps may be on any of the following bases.

- Fixed rate–fixed rate

- Fixed rate–floating rate

- Floating rate–floating rate

As can be perceived from the illustration, a swap transaction such as this enables each party to service the debt of the counterparty. Bank Atlantic has taken a dollar-denominated loan. It will service it using the dollar-denominated payments that it receives every six months from Bank Europeana. Similarly, Bank Europeana has taken a loan denominated in euros, which it will service using the euro-denominated payments it receives periodically from Bank Atlantic.

CROSS-CURRENCY SWAPS

Technically speaking the term currency swap is applicable only for transactions that entail the exchange of cash flows computed on a fixed-rate–fixed-rate basis, such as the deal that we have just studied. Currency swaps where one or both payments are based on a floating rate of interest should strictly speaking be termed as cross-currency swaps. Within cross-currency swaps, we make a distinction between coupon swaps that are on a fixed-rate–floating-rate basis and basis swaps on a floating-rate–floating-rate basis.

VALUATION

We will explore the mechanics of currency swap valuation by focusing on the swap between Bank Atlantic and Bank Europeana. The swap may be viewed as a combination of the following transactions. Assume that Bank Atlantic has issued a fixed-rate bond in euros with a principal of €6MM and converted the proceeds to dollars at the spot rate of 0.8000 USD-EUR. The proceeds in dollars can be perceived as having been invested in fixed-rate bonds denominated in dollars. From the perspective of the counterparty the transaction may be perceived as follows. Assume that Bank Europeana has issued fixed-rate dollar-denominated bonds with a face value of $7.50MM, converted the proceeds to euros at the prevailing spot rate, and invested the equivalent in euros in fixed-rate bonds in that currency. Thus, every six months Bank Atlantic will receive interest in dollars and pay interest in euros, while Bank Europeana will pay interest in dollars and receive interest in euros. Thus, a currency swap between two parties is equivalent to a combination of transactions in which each party issues a bond in one currency to the other and uses the proceeds to acquire a bond issued by the counterparty. Quite obviously the fixed rate that is applicable in either currency is the coupon rate that is associated with a par bond in that currency, as we have seen in the case of fixed-floating interest rate swaps. Because two currencies are involved, however, we need the term structure of interest rates for both currencies.

Consider the data given in Table 10.8.

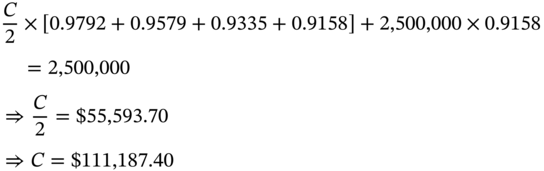

The value of the fixed rate for USD may be determined as follows. Consider a bond with a face value of $2.50MM. The coupon for a par bond denominated in USD is given by:

This corresponds to a rate of 4.4475% per annum.

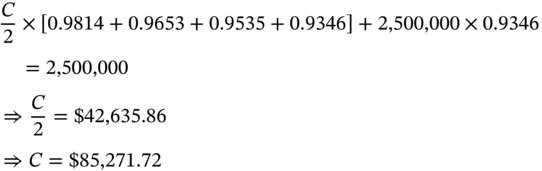

Similarly, we can compute the coupon for a bond denominated in euros.

This corresponds to a coupon of 3.4109% per annum.

TABLE 10.8 Term Structure for US Dollars and the Euro

| Time to Maturity | USD-LIBOR | Discount Factor | Euro-LIBOR | Discount Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-months | 4.25% | 0.9792 | 3.80% | 0.9814 |

| 12-months | 4.40% | 0.9579 | 3.60% | 0.9653 |

| 18-months | 4.75% | 0.9335 | 3.25% | 0.9535 |

| 24-months | 4.60% | 0.9158 | 3.50% | 0.9346 |

If the swap had been such that the rate for dollars was fixed while that for the payment in euros was variable, then the applicable rate would be 4.4475% for the dollar-denominated payments and LIBOR for the counterpayments. On the other hand, if the rate were to be fixed for the payments in euros and variable for the dollar-denominated payments, the applicable rate would be LIBOR for the payment in dollars and 3.4109 for the payments in euros. Finally, if payments in both currencies were to be on a floating-rate basis, it would be LIBOR for LIBOR.

CURRENCY RISKS

A currency swap, as we would expect, exposes both the parties to currency risk. Let us consider the swap where Bank Atlantic borrows and makes a payment of $7.50MM to Bank Europeana in return for a counterpayment of €6.00MM. The exchange rate for the cash flow swap was 0.8000 USD-EUR.

At maturity Bank Europeana would pay back $7.50MM to the US bank and would receive €6.00 MM in return. Let us assume that in the intervening three years, the dollar has appreciated to 0.8125 USD-EUR. Bank Atlantic would benefit from the fact that the terminal exchange of principal is based on the original exchange rate of 0.8000 USD-EUR. If 6MM euros were to be converted at the prevailing rate of 0.8125 USD-EUR, Bank Atlantic would stand to receive only $7,384,615. Therefore, the counterparty slated to receive the currency that has appreciated during the life of the swap stands to gain from the fact that the terminal exchange of principal is based on the exchange rate prevailing at the outset, while the other party stands to lose. In our illustration, while Bank Atlantic avoids a loss of $115,385 USD, Bank Europeana forgoes an opportunity to save an identical amount.

HEDGING WITH CURRENCY SWAPS

An interest rate swap can be used as a mechanism for hedging foreign currency exposure. Telekurs, a telecom company based in Frankfurt, has issued a Yankee bond for $25MM, carrying interest at the rate of 6% per annum payable semiannually. The bonds have four years to maturity and the company seeks to hedge its exposure to the US dollar-Euro exchange rate, because all its income is primarily denominated in euros. Assume that the current exchange rate is 0.8000 USD-EUR.

The company can use an interest rate swap to hedge its currency exposure. Because it has a payable in US dollars, it needs a contract wherein it will receive cash flow in dollars and make payments in euros. If the company is of the opinion that rates in the eurozone are likely to rise, it can negotiate a swap wherein it makes a fixed-rate-based payment in euros to a counterparty in exchange for a fixed-rate-based income stream in dollars. The dollar inflows should be structured to match the company's projected outflows in that currency. This will lead to a situation where its exposure to the dollar is perfectly hedged.

NOTES

- 1 In some swap markets the fixed rate payer is termed as the buyer and the counterparty is termed as the receiver.

- 2 The discount factor for a given maturity is the present value of a dollar to be received at the end of the stated period.

- 3 See Coyle (2001).

- 4 See Geroulanos (1998).

- 5 See Geroulanos (1998).