Chapter 4

Using All of Your Censuses

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Locating census records online

Locating census records online

![]() Using U.S. census schedules

Using U.S. census schedules

![]() Discovering state, territorial, and special records

Discovering state, territorial, and special records

![]() Researching non-U.S. census records

Researching non-U.S. census records

Although some people believe that the census is a nuisance every ten years, genealogists and family historians believe it’s one of the most important sources of information. Censuses give us periodic snapshots of the composition of a household and are valuable for filling in the gaps in the lives of our ancestors. For example, if you look at the birth and death places for William Henry Abell (see Chapter 2 for the information that we gathered on him), you would think he lived all his life in Kentucky. By reviewing census records, we discover that he lived a number of places in Kentucky and Illinois.

Not so many years ago, only bits and pieces of transcribed censuses were online. Now, most comprehensive subscription sites contain digitized and indexed census records for the United States. Also, sites are making strides in placing census records for other countries online.

In this chapter, we show you what census records are currently available and describe some of the major projects that you can use as keys for unlocking government treasure chests of genealogical information.

Coming to Your Census

We like to think of researching an ancestor through census records like tracking a submarine. Every so often the submarine emerges, submerges, and then resurfaces. You don’t really know the direct path the submarine took between the two points, but at least you can guess the general direction it’s moving based on where it started and where it ended. Census records are similar in that you can use one census record as a starting point and a second census record (in a different year) as an ending point. Then you can look at common migration paths to predict the path your ancestor might have taken to get to his or her final destination.

To effectively use census records, it’s important to understand what information they include and why they were created. Census records are periodic counts of a population by a government or organization. These counts can be conducted at regular intervals (such as every ten years) or special one-time counts made for a specific reason.

Detailed population census records are valuable for tying a person to a place and for discovering relationships between individuals. For example, let’s take our William Henry Abell. We’re not sure who his father was, but we do know that he was born in Kentucky. By using a census index, you may be able to find a William Henry Abell listed in a Kentucky census index as a member of someone’s household. If the information about William in that record (age, location, and siblings’ names) fits what you know from a family interview, you may have found one or more generations to add to your genealogy. You can use the name of the head of household and his or her spouse as a lead to investigate in identifying William’s parents.

Often a census includes information such as a person’s age, sex, occupation, birthplace, and relationship to the head of the household. Sometimes the enumerators — the people who conduct the census — add comments to the census record (such as a comment on the physical condition of an individual or an indication of the person’s wealth) that may give you further insight into the person’s life.

United States census schedules

Federal census records in the United States have been around since 1790. Within the United States, censuses are conducted every ten years to count the population for a couple of reasons — to correctly divide the number of seats in the U.S. House of Representatives and to assess federal taxes. Although census collections are still performed, privacy restrictions prevent the release of any detailed census information on individuals for 72 years. Currently, you can find federal census data on individuals for the census years 1790 to 1940. However, practically all of the 1890 census was destroyed due to actions taken after a fire in the Commerce Building in 1921 — for more on this, see “First in the Path of the Firemen,” The Fate of the 1890 Population Census, at

https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1996/spring/1890-census-1.html.

Federal census records are valuable because you can use them to take historical snapshots of your ancestors in ten-year increments. These snapshots enable you to track your ancestors as they moved from county to county or state to state, and to identify the names of parents and siblings of your ancestors who you may not have previously known. Also, by paying attention to neighbors listed in the census or by individuals who cohabitated with your ancestors, you may be able to determine families that later intermarried with your ancestor’s family or discover why a family member was given a particular first name. For example, a child’s first name might have been named after a close neighbor’s last name.

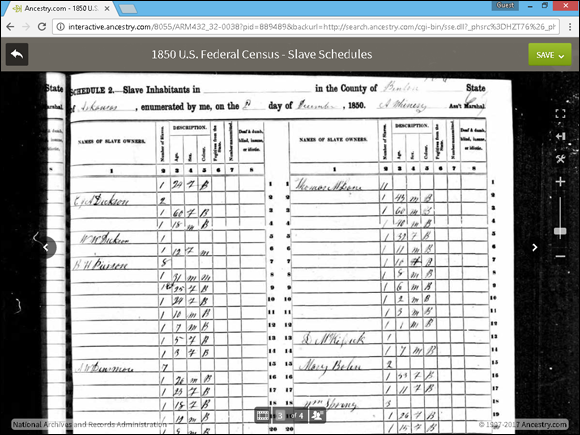

Population schedules were not the only product of the federal censuses. Special schedules include census returns for slaves, mortality, agriculture, manufacturing, and veterans. Each type of special schedule contains information pertaining to a specific group or occupation. In the case of slave schedules (used in the 1850 and 1860 censuses), slaves were listed under the names of the slave owner, and information was provided on the age, gender, and race of the slave. If the slave was more than 100 years old, his or her name was listed on the schedule. Note, though, that enumerators may have included names for other slaves if he or she felt inclined to list them. Although the slave schedules do not contain a lot of information, they can be used as a starting point for further research. Figure 4-1 shows an example of a slave schedule from the 1850 census.

FIGURE 4-1: 1850 slave schedule for Benton County, Arkansas.

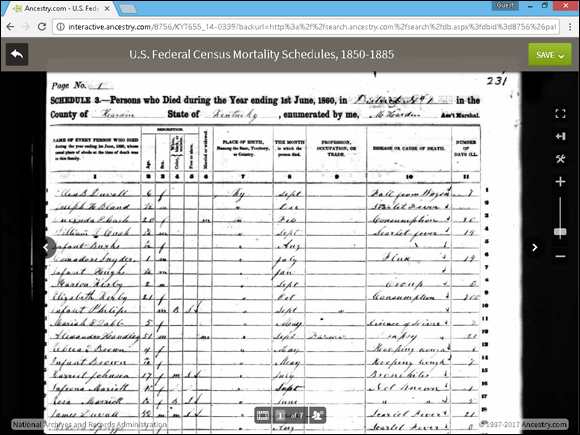

Mortality schedules (used in 1850, 1860, 1870, and 1880) include information on people who died in the 12 months previous to the start of the census. For example, the 1860 schedule contains details such as name, age, sex, color, free or slave, married or widowed, place of birth, month of death, profession, cause of death, and number of days ill. Figure 4-2 shows a page from the 1860 schedule.

FIGURE 4-2: 1860 mortality schedule for Hardin County, Kentucky.

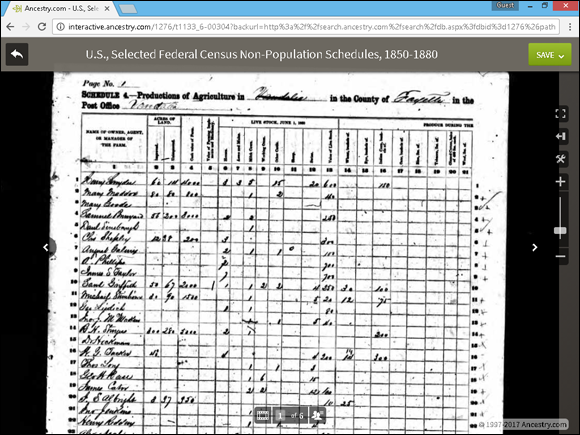

Agricultural schedules were used between 1840 and 1910. However, only the schedules from 1840 to 1880 survive. They contain detailed demographic and financial information on farm owners. Information contained on the schedules includes name of owner or manager of the farm, acres of land, cash value of the farm, value of implements and machinery, number and value of livestock, value of produce, and value of animals slaughtered; see Figure 4-3.

FIGURE 4-3: 1860 agriculture schedule for Vandalia, Fayette County, Illinois.

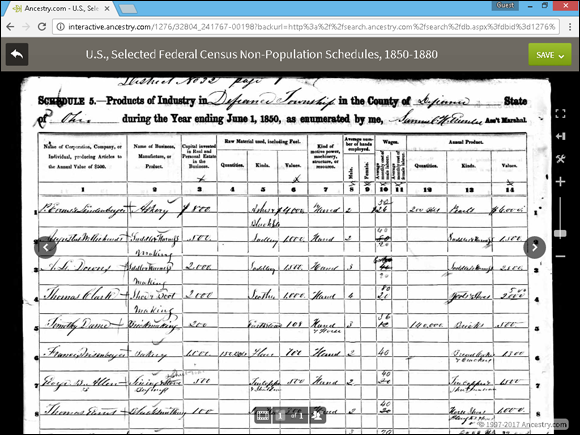

Manufacturing and industry schedules (taken infrequently between 1810 and 1880) contain information on business owners and their business interests. Details included on the 1850 schedule included the name of the company, product manufactured, capital invested, raw material used, kind of power used, average number of people employed, wages paid, and annual product produced; see Figure 4-4.

FIGURE 4-4: 1850 industry schedule for Defiance County, Ohio.

Veteran schedules include the Revolutionary War pensioner census, which was taken as part of the 1840 census, and the special census for Union veterans and their widows (taken in 1890). Information found on the 1890 special census includes rank, company, regiment or vessel, date of enlistment, date of discharge, and length of service. The remarks section includes information on disability and other comments the enumerator felt compelled to make. Figure 4-5 contains an example of the 1890 special schedule, including surviving soldiers, sailors, marines, and widows.

FIGURE 4-5: 1890 veteran special schedule.

State, territorial, and other census records

Federal census records are not the only population enumerations you can find for ancestors in the United States. You may also find census records at the state, territorial, and local level for certain areas of the United States.

Several state and territorial censuses have become available online. Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com) has, within its subscription collection, state and territorial censuses for Alabama (1820–1866), California (1852), Colorado (1885), Florida (1867–1945), Illinois (1825–1865), Iowa (1836–1925), Kansas (1855–1925), Michigan (1894); Minnesota (1849–1905), Mississippi (1792–1866), Missouri (1844–1881), Nebraska (1860–1885), Nevada (1875), New Jersey (1895), New York (1880, 1892, 1905), North Carolina (1784–1787), North Dakota (1915, 1925), Oklahoma (1890, 1907), Rhode Island (1865–1935), South Dakota (1895), Washington (1857–1892), and Wisconsin (1895, 1905), as well as a host of other census records, including images of the U.S. Indian census schedules from 1885 to 1940.

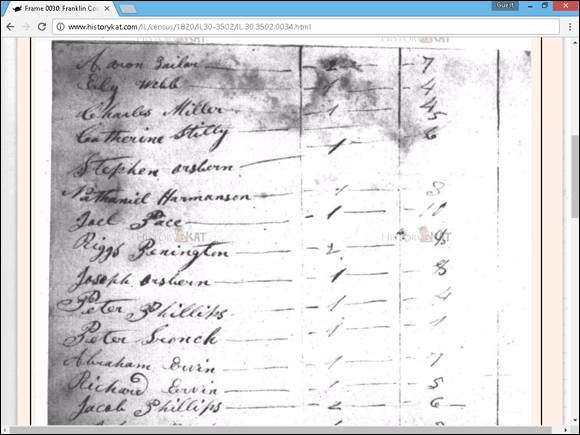

Another source for state and territorial census images is at the free site HistoryKat (www.historykat.com). HistoryKat has images of Illinois (1810–1820). Figure 4-6 shows an image from the 1820 Illinois state census for Franklin County.

FIGURE 4-6: The 1820 Illinois state census for Franklin County.

Indexes and some images for state and territorial censuses are also found at no charge on FamilySearch (www.familysearch.org). Locations available on the site include Alabama (1855, 1866), California (1852), Colorado (1885), Florida (1885, 1935, 1945), Illinois (1855, 1865), Iowa (1885, 1895, 1905), Massachusetts (1855, 1865), Michigan (1894), Minnesota (1865–1905), New Jersey (1855, 1865, 1885, 1895, 1905, and 1915), New York (1855–1925), Rhode Island (1885–1935), and South Dakota 1905–1945).

Special census records can often help you piece together your ancestors’ migration patterns, account for ancestors who may not have been enumerated in the federal censuses, or provide greater details on ancestors who were members of a specific population. Some examples of special censuses available at Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com) include

- Census of merchant seamen, 1930: Enumerates the name of each person on board, sex, race, age, marital status, ability to read/write, place of birth, citizenship status, ability to speak English, occupation, whether the person was a veteran mobilized for war/expedition, and address of next of kin

- New York census of inmates in almshouses and poorhouses, 1830–1920: Contains name, age, date of admission and discharge, habits, education, names and addresses of relatives and friends, questions on extended family, and questions on tendency toward self-sufficiency or dependence

- Puerto Rico, special censuses, agricultural schedules, 1935: Lists the names of owners and managers of farms, acreage, farm value, machinery, livestock, and amount of staples produced on the farm

- U.S. special census on deaf family marriages and hearing relatives, 1888–1895: Contains information on how the person became deaf and other relatives that might also be deaf

- U.S. special census of Indians, 1880: Includes Indian name, English translation of the name, whether a chief, whether full-blooded, number of years on the reservation, and health information

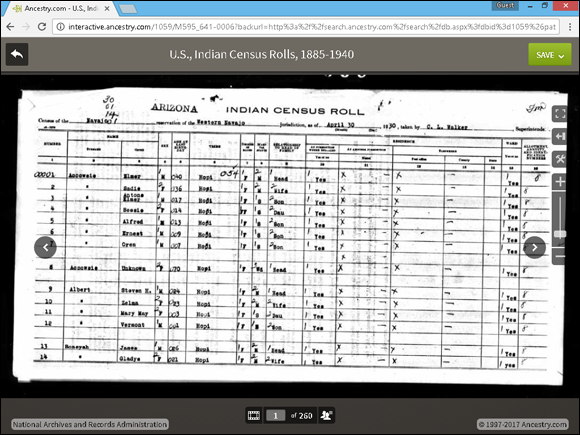

- U.S. Indian census rolls, 1885-1940: A collection of several censuses performed on Indian reservations; see Figure 4-7

FIGURE 4-7: The 1880 special census of Indians.

Finding Your Ancestors in U.S. Census Records

Imagine that you’re ready to look for your ancestors in census records. You hop in the car and drive to the nearest library, archives, or Family History Center. On arrival, you find the microfilm roll for the area where you believe your ancestors lived. You then go into a dimly lit room, insert the microfilm into the reader, and begin your search. After a few hours of rolling the microfilm, the back pain begins to set in, cramping in your hands becomes more severe, and the handwritten census documents become blurry as your eyes strain from reading each entry line by line. You come to the end of the roll and still haven’t found your elusive ancestor. At this point, you begin to wonder if a better way exists.

Fortunately, a better way does exist for finding and accessing U.S. census records. The easiest way, if you have the financial means, is to subscribe to a site that has indexed census records that link to images of the census microfilm. These sites include Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com), findmypast.com (www.findmypast.com), and MyHeritage (www.myheritage.com). The free site, FamilySearch (www.familysearch.org) also has indexed census records. You can normally access the census records through the standard search mechanism on the site. If you need a refresher on searching these sites, see Chapter 3.

Sifting through census record results

Figure 4-8 shows some of the results from Ancestry.com. A total of 3,818 results came back and only a very few will pertain to William. After all, during his lifetime there were only eight censuses — 1880, 1890, 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930, 1940, and 1950. The 1890 census is unavailable due to the actions taken after the fire in the Commerce Building in 1921 and the 1950 census is not available to the public until 2022 (due to privacy restrictions). This leaves six census years for research — a very manageable number.

FIGURE 4-8: Census search results from Ancestry.com.

Here is a quick evaluation of the search results:

- Search result 1: The result is from the 1900 census. The search record matches the following elements that we assembled in Chapter 2: William H Abell, Lizzie F Abell, and birthdate of January 1873.

- Search result 2: The result is from the 1910 census. The search record matches: William H Abell, Lizzie F Abell, Leona P Abell, [Ella E Abell], birth about 1873 in Kentucky.

- Search result 3: The result is from the 1920 census. The search record matches William K Abell, Leona P, Edna E, birth around 1873 in Kentucky. The middle initial error is not uncommon in indexing — sometimes it is hard to read the handwriting of the census enumerator.

- Search result 4: The result is from the 1900 census. The search record matches William Abell, but no other element except a birth in Kentucky. The birthdate is close — 1872, but we already have a better match for the 1900 census in the first search result.

- Search result 5: The result is from the 1930 census. The search record matches William Abell, Betty Abell, birth around 1873 in Kentucky. Keep in mind that William was married to a Betty at the time of his death, according to his obituary.

- Search result 6: The result is from the 1880 census. The search record matches William H, but the last name is spelled Abl. The birth date and place are a match — about 1873 in Kentucky. It is not unusual to see name spelling variations in census records. Some enumerators spelled the name like it sounded.

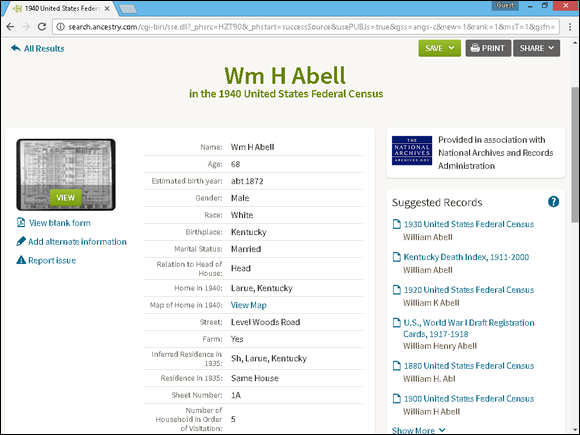

In the first six search results, we had pretty good luck. Five census records match our target ancestor. Of course, you may be asking where the 1940 census is. It doesn’t appear until search result number 36. This is probably because the first name is abbreviated Wm H Abell with a birth date of about 1872. The abbreviation and conflicting year of birth prompted the entry for the 1940 census to drop down in the search results. Of course, if you knew you were missing one census year (1940), you could click on the 1940s link in the left column to filter the results. Doing that makes the Wm H Abell result number 2 on the list.

Our next step is to look at the digitized records to confirm the information from the index and to see what other nuggets are in the record.

Digging into digitized census records

We think that the best part of family history research is when you are able to see the actual record that is evidence of the existence of your ancestor. You never know what surprising information you may encounter.

FIGURE 4-9: The record page for the 1940 census.

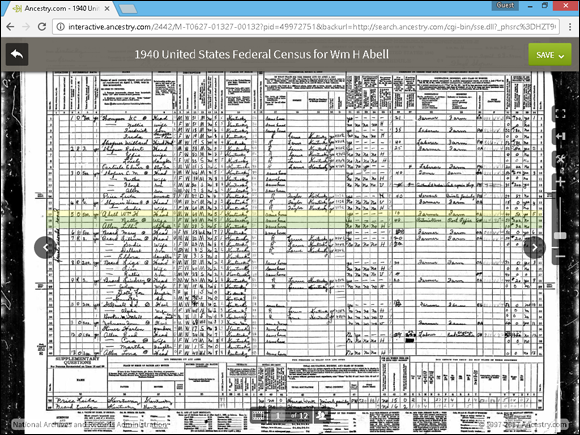

If you click on the View button on the thumbnail of the census record, you are taken to the image viewer (see Figure 4-10). To make it easy to find your ancestor, the information matching the search result is highlighted on the page. In the next few paragraphs, we go through the schedule so that you know where to look for all the relevant information provided by the record.

FIGURE 4-10: The image of the enumeration page for Wm H Abell in the 1940 census.

The first important element of a census enumeration is at the top of the page. Starting on the left side, the schedule states that the record is from Larue County, Kentucky. In particular, the page was enumerated in the Magisterial District Number 3, Buffalo. This provides us with a geographical landmark for the schedule. The Supervisor’s District (Number 4) and Enumeration District (Number 62-7) numbers are found in the upper right corner of the schedule. These can also be used to locate where the enumerator was when the record was created. These can be very handy in rural areas where addresses were not always used. The final piece of critical evidence is the date of the enumeration — 23–24 April 1940. You have the actual date that the enumerator asked the questions. This date can help explain why an individual may not be listed in the census (for example, they were born in 1940, but after the enumeration date).

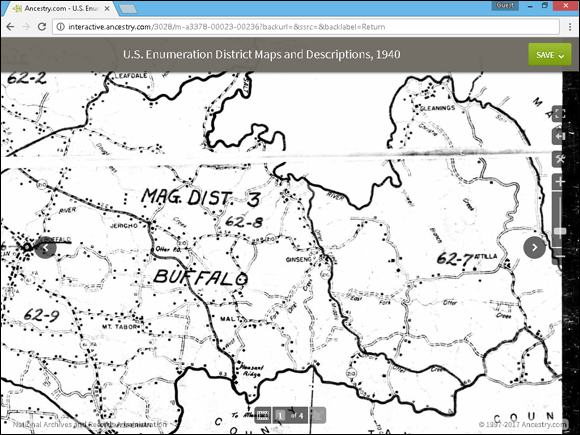

Armed with the enumeration district number, we can find a digitized map of the 1940 enumeration districts at the National Archives Web or Ancestry.com websites. An easy way to find the map is to use Steve Morse and Joel Weintraub’s Viewing 1940 Enumeration District Maps in One Step web page. Try this:

-

Point your browser to

http://stevemorse.org/census/arc1940-1950edmaps.html?year=1940.The page appears with drop-down boxes for the state, county, and city.

-

Set the drop-down boxes to your desired location and click the Get ED Map Images button.

We set the state to Kentucky and county to Larue County. A new page appears with links to the National Archives viewer (preferred if you don’t have an Ancestry.com subscription), the image files on the National Archives site, and the Ancestry.com viewer.

-

Click a link to view the enumeration district map.

We clicked on the Ancestry.com viewer, so we could link the map to William Henry Abell’s record on our online family tree. The map appears in a separate browser window as seen in Figure 4-11.

FIGURE 4-11: The Enumeration District map for Magisterial District Number 3.

Consolidating your discoveries

As you can see, we learned a lot about William and his family from the record that we covered in the last section. We can compare his information to his neighbors to get a sense of the community that he lived within. Up to now we’ve engaged in the planning phase and researching phase. Now, it’s time to move into the consolidation phase and store our information. As we have confirmed that the information in the census record is consistent with what we knew about William, we can save the information to our Ancestry.com online family tree (even if you don’t have an Ancestry.com family tree, you can save the record to your computer). Here is how:

-

Click the green Save button.

The button is located in the upper-right corner of the viewer. A drop-down box appears with choices on where to save the record.

-

Choose a location to save the record.

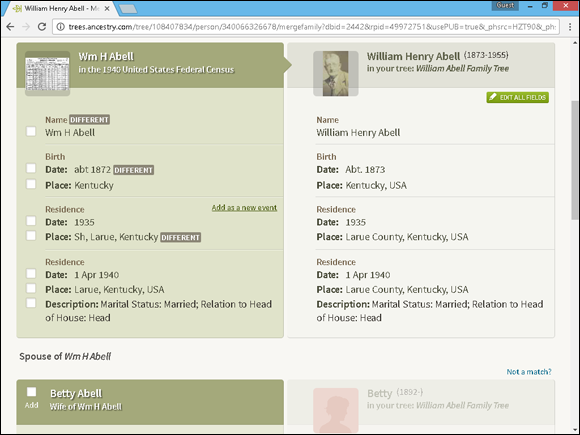

We chose to save it to William Henry Abell online family tree record. A new page appears comparing information from the record to the current information stored in William’s online family tree record (see Figure 4-12).

-

Select the information that you wish saved to the online family tree.

Use the checkboxes to select the information. Note that the box specifies information that is different from the record in the online family tree, as well as, those items that are new. If the person’s box is grayed out, click on the checkbox next to their name.

-

Optionally, edit any information that needs clarification by clicking on the Edit All Fields button located in the right column. Click the Close Editing button when the edits are complete.

In our example, the residence entry for 1935 shows the place as Sh, Larue, Kentucky. “Sh” isn’t really a place — it is a code from the census meaning “Same House.” So, we edited the field to say “Larue County, Kentucky, USA.”

-

Click the Save to Your Tree button.

The facts page appears for the person to whom you saved the record.

FIGURE 4-12: The Add New Information to Your Tree page.

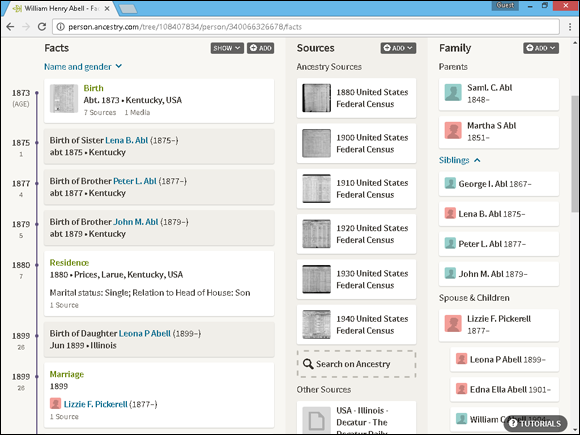

Figure 4-13 shows the updated facts page for William Henry Abell. Notice that the 1940 United States Federal Census box was added to the Sources column and is linked to three facts (the purple lines drawn from the source to the fact shows the link). Also, see that a new entry shows under Web Links — to the 1940 Enumeration District Map. Notice that Lillie Allen has been added as a child under Betty. Because Lillie was a step-daughter, we edit the entry to show that William was not the biological father.

-

Click on the box of the person you want to edit.

We clicked on the Lillie Allen box under the Spouse & Children section of the Family Column. The facts page for the person appears.

-

Click on the Edit drop-down button.

The button is located in the upper-right corner of the screen (a pencil icon is on the button). A drop-down menu appears.

-

Select Edit Relationships and change the relationship information.

A pop-over box appears. You can choose to add an alternative father or mother or change the relationship of the current parent. We don’t know Lillie’s father, so we change William Henry Abell’s drop-down from Biological to Step. If we discover the identity of Lillie’s father in the future, we can associate her with him later.

-

Click the “X” button in the upper-right corner to dismiss the pop-over box.

The facts page appears.

FIGURE 4-13: William Henry Abell’s facts page with new information.

Using census records to tell a story

Family history is more than collecting the names and birth/death dates of people who lived in the past. It is about telling the story of their lives. Your ancestor was more than a line number on a census schedule within a particular county and state. They had jobs, possessed land, were educated at a certain level, and had relationships with the community around them.

As a final step in the consolidation phase, we should write up the results of our research on the census record and put it into our genealogy application. In our case, we add it to the Ancestry.com online family tree LifeStory page. Here’s how:

-

From the Pedigree view, click your ancestor’s box and select the Profile button.

We selected William Henry Abell’s box and clicked on the Profile button. The facts page appears.

-

Click on the LifeStory link.

The LifeStory link is located in the menu just under the name of the ancestor. The LifeStory timeline appears with facts, maps, and historical articles, as seen in Figure 4-14.

-

Edit a fact to provide additional details from the census record.

We scrolled down to the fact dated 1 April 1940 — marked “Residence, William Henry Abell lived in Larue, Kentucky, on April 1, 1940.”

-

Click the Edit button.

The Edit button is located in the upper-right corner of the fact. The fields in the fact become editable. Type or cut and paste information into the fields. We put our discoveries into the third field and adjusted the date to be the actual date on the census schedule.

-

Click the Save button.

The text saves in the field.

FIGURE 4-14: William Henry Abell’s LifeStory page.

To complete the research on census records, we would repeat the process for each census year. To triangulate information, compare the results from each census year. Table 4-1 shows an abstract of the information that we discovered in each census year.

TABLE 4-1 Information from Census Years

|

Census |

1940 |

1930 |

1920 |

1910 |

1900 |

1880 |

|

Name |

Abell, Wm H |

Abell, William |

Abell, William K. |

Abell, William H. |

Abell, William H. |

Abl, William H. |

|

Location |

Kentucky – Larue County |

Illinois – McLean County |

Illinois – De Witt County |

Illinois – Tazewell County |

Illinois – De Witt County |

Kentucky – Larue County |

|

Age |

68 |

57 |

47 |

37 |

27 |

7 |

|

Birthplace |

Kentucky |

Kentucky |

Kentucky |

Kentucky |

Kentucky |

Kentucky |

|

Owned/Rented |

Owned |

Rented |

Rented |

Rented |

Rented | |

|

Value of Home |

500 |

215 | ||||

|

Occupation |

Farmer |

Blacksmith |

Farmer |

Blacksmith |

Farm Laborer | |

|

Spouse |

Betty |

Betty |

N/A |

Lizzie F. |

Lizzie F. | |

|

Other Members of Household |

Allen, Lillie |

Allen, Lillie Allen, Nancy Allen, Evelyn Allen, Howard Abell, Harland |

Abell, Leona P. Abell, Edna E. Abell, William C. Abell, Lillian M. Abell, Harland V. |

Abell, Leona P. Abell, Ella E. Abell, William C. Abell, Lillian M. |

Abell, Neona P. |

Abl, Samuel C. Abl, Martha S. Abl George I. Abl, Lena B. Abl, Peter L. |

|

Date |

23-24 April 1940 |

29 April 1930 |

15-16 January 1920 |

04 May 1910 |

06 June 1900 |

01 June 1880 |

After looking through the six censuses, we pieced together the following new information about William Henry Abell. William lived in four counties in two states — starting and ending in Larue County (Kentucky), with stops in De Witt County (Illinois), Tazewell County (Illinois), and McLean County (Illinois). He was first married to Lizzie F. Pickerell around 1899 (1900 census) and married Betty between 1920 and 1930 (1930 census). We also have the approximate birth dates and states of Lizzie and Betty, five children, four step-children, and four siblings. Finally, we have the names and birth dates and states for William’s parents (1880 census). By looking at six records we expanded the number of facts on William’s online family tree page from three to eighteen (see Figure 4-15).

FIGURE 4-15: William Henry Abell’s facts page after census research.

Census Records from Afar

Of course, the U.S. isn’t the only country to carry out census enumerations. Several countries around the world have taken periodic snapshots of the population. The frequency of these enumerations wasn’t always every ten years and wasn’t always for the same purposes as in the U.S. Details on censuses are found as follows. We indicated whether there are online sources for the records.

Africa

- Ghana: FamilySearch has added images of census records from 1984.

Asia

- Japan: FamilySearch.org hosts census records from Ehime-ken from 1661-1875 at

https://familysearch.org/search/collection/2313184. - Philippines: Censuses were taken by the United States for military personnel in 1900, 1910, and 1920 and are available on Ancestry.com. A census was also conducted in 1903 and is available on the Internet Archive at

https://archive.org/details/censusphilippin01ganngoog.

Europe

- Albania: FamilySearch.org has unindexed images of the 1930 census available online.

- Austria: Some general information is available on the content of the Galicia censuses and is contained in two articles on the Federation of East European Family History Societies site: Austrian Census Returns from 1869 to 1890 (

http://feefhs.org/region/galicia-census-returns) and Austrian Census for Galicia (http://feefhs.org/region/galicia-austrian-census). FamilySearch.org has posted census records for Wels, Upper Austria, citizen rolls for Linz 1658-1937, and Vienna population cards 1850-1896. - Czech Republic: The South Bohemian Census 1857–1921 contains digitized images from the 1857, 1869, 1880, 1890, 1900, 1910, and 1921 censuses. You can find the images at

http://digi.ceskearchivy.cz/DA?lang=en&menu=0&doctree=1t&id=5. FamilySearch has placed more than 4.9 million images of census records and registers from 1800-1990 athttps://familysearch.org/search/collection/1930345. - Denmark: The Danish Archives has census returns for the years 1787, 1801, 1834, 1840, 1845, 1850, 1855, 1860, 1870, 1880, 1890, 1901, 1906, 1911, 1916, 1921, 1925, 1930, and 1940. You can find information from these censuses at the Statens Arkiver site (

https://www.sa.dk/ao-soegesider/da/collection/theme/2) and the Dansk Demografisk Database (http://ddd.dda.dk/kiplink_en.htm). The Dansk Demografisk Database also includes censuses and lists of emigrants and immigrants for Denmark. FamilySearch.org hosts the 1911 and 1916 censuses. MyHeritage (www.myheritage.com) has the 1901, 1906, 1911, 1916, 1921, 1925, and 1930 censuses online. Police Registers from Copenhagen 1890-1923 are available athttp://www.politietsregisterblade.dk./index.php. Censuses for the county of Aarhus are online atwww.folketimidten.dk. - Estonia: FamilySearch has placed over 600,000 images of population registers from Estonia. Years covered include 1918 through 1944.

- Finland: MyHeritage (

www.myheritage.com) has church census and pre-confirmation books dated 1657-1915 available online. - France: FamilySearch.org has indexes and images for the 1856 and 1876 censuses for Dordogne, France; and the 1830-1831, 1872, 1886, and 1891 censuses for Haute-Garonne, Toulouse, France. The English census of Pondichéry is available on the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at

http://web.archive.org/web/20051018170723/http://pondichery.ifrance.com/index.html. - Germany: The collection at Ancestry.com contains the Mecklenburg-Schwerin censuses of 1819, 1867, 1890, 1900, and 1919; the Lübeck census of 1807, 1812, 1815, 1831, 1845, 1851, 1857, 1862, 1871, 1875, and 1880. FamilySearch (

https://familysearch.org) and MyHeritage (www.myheritage.com) has also posted the Mecklenburg-Schwerin censuses of 1867, 1890, and 1900. - Hungary: Ancestry.com has the 1869 All Citizen Census, assorted census records from 1781-1850, Jewish Census of 1848, and Jewish names in property tax census of 1828. The National Archives of Hungary collection (

http://mnl.gov.hu) includes the 1623, 1631, 1691, 1715,1775, 1787, and 1828 Urbarial Census; Jewish Census of 1848; 1857 Census, and 1877 Census. - Iceland: The National Archives of Iceland Census database (

http://www.manntal.is/?lang=en) includes records from the censuses of 1703, 1816, 1835, 1840, 1845, 1850, 1855, 1860, 1870, 1880, 1890, 1901, 1910, and 1920. Ancestry.com hosts the censuses from 1870, 1880, and 1890. - Ireland: The 1901 and 1911 censuses, along with fragments and substitutes from 1821-1851 are available online at

www.census.nationalarchives.ie. The following records are available at Ancestry.com — 1766 Religious Census, Census Abstracts 1841-1851, 1901 Census, and 1911 Census. Findmypast (www.findmypast.com) hosts records from the 1821–1851 census, 1901 and 1911 censuses, 1922 Army Census, and Census of Elphin of 1749. FamilySearch.org has the 1821, 1831, 1841, and 1851 censuses. MyHeritage (www.myheritage.com) has the 1901 and 1911 censuses and the 1851 Dublin city census. - Italy: FamilySearch.org contains census records from 1750–1900 for Mantova.

- Moldova: FamilySearch.org has image only collections of Poll Tax Census (Revision Lists) and Census Lists 1796–1917. Ancestry.com has the Bessarabia, Revision Lists, 1837–1952.

- Luxembourg: FamilySearch has uploaded 1.1 million images of census records from 1843 to 1900 at

https://familysearch.org/search/collection/2037957. - Netherlands: FamilySearch houses census and population registers from 1574 to 1940 and Noord-Brabant Province population registers from 1820 to 1930. Ancestry.com has the Population Registers Index, 1850–Present and Census and Population Registers, 1645–1940 collections.

- Norway: The National Archives of Norway (

https://media.digitalarkivet.no/en/ft/browse) maintains online the censuses of 1663-1666, 1701, 1769, 1801, 1815, 1825, 1835, 1845, 1855, 1865, 1870, 1875, 1885, 1891, 1900, and 1910. FamilySearch.org, MyHeritage, and Ancestry.com have the 1875 Census. - Poland: Ancestry.com has the Będzin Jewish Census, 1939.

- Romania: Ancestry.com hosts the Jewish Census, 1942.

- Russia: FamilySearch contains Tver Confession Lists 1728–1913 and Tartarstan Confession Lists 1775–1932. Ancestry.com has the Jewish Families in Russian Empire Census, 1897.

- Slovakia: FamilySearch.org hosts images from the 1869 Census.

- Spain: FamilySearch houses the Catastro de Ensenada, 1749–1756.

- Sweden: The National Archives houses a database of the 1860, 1870, 1880, 1890, 1900, 1910, and 1930 censuses at

https://sok.riksarkivet.se/folkrakningar. The Research Archives, Umeå University Library houses the 1890 Census athttp://www2.foark.umu.se/census/Index.htm. - Switzerland: FamilySearch.org contains census enumerations from Fribourg for the years 1811, 1818, 1831, 1834, 1836, 1839, 1842, 1845, 1850, 1860, 1870, and 1880.

- Ukraine: FamilySearch.org has the Odessa Census Records 1897.

- United Kingdom: For general information on census records, see the National Archives Census page at

www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/records/looking-for-person/recordscensus.htm. Images of the 1841 through 1911 censuses are available at Ancestry.com, FindMyPast.com (www.findmypast.co.uk), Genes Reunited (www.genesreunited.co.uk), and MyHeritage. Transcriptions are sporadic for the 1841 through 1891 censuses at the FreeCEN site (http://www.freecen.org.uk) and TheGenealogist.co.uk (www.thegenealogist.co.uk).

North America

- Canada: Library and Archives Canada maintains information on the 1825, 1831, 1842, 1851, 1861, 1870, 1871, 1881, 1891, 1901, 1906, 1911, and 1916 censuses online at

www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/census/Pages/census.aspx. Ancestry.ca (www.ancestry.ca) has the 1825, 1842, 1851, 1861, 1871, 1881, 1891, 1901, 1906, 1911, 1916, and 1921 censuses. MyHeritage (www.myheritage.com) hosts the 1825, 1842, 1861, 1871, 1881, 1891, 1901, and 1911 censuses. FamilySearch.org has the 1901 and 1916 censuses. - Guatemala: FamilySearch.org, Ancestry.com and MyHeritage contain the Cuidad de Guatemala Census of 1877.

- Mexico: FamilySearch.org and Ancestry.com have the 1930 Census.

Oceania

- Australia: Individual state censuses date 1788. The first country-wide census was conducted in 1881. Most returns were destroyed, in accordance with law. You can substitute other records for census returns in the form of convict returns and musters and post office directories. These returns are available for some states for the years 1788, 1792, 1796, 1800, 1801, 1805, 1806, 1811, 1814, 1816, 1817–1823, 1825, 1826, and 1837. FamilySearch.org offers the New South Wales 1828, 1841, and 1891 censuses and Ancestry.com has the 1901 census for New South Wales online. A portion of the 1913 census is available at

http://www.hotkey.net.au/~jwilliams4/act1913.htm. For more information on locating census returns, see the Census in Australia page atwww.jaunay.com/auscensus.html.

South America

- Argentina: The first two national censuses were conducted in 1869 and 1895, and a census was conducted in 1855 for Buenos Aires. These censuses are available online at FamilySearch.org, MyHeritage and Ancestry.com. The 1914 national census is only available at the Archivo General de la Nación.

- Peru: FamilySearch.org hosts the Municipal Census, 1831–1866.

Each census year contains a different amount of information, with more modern census returns (also called schedules) containing the most information. Schedules from 1790 to 1840 list only the head of household for each family, along with the number of people living in the household broken down by age classifications. Schedules from 1850 on have the names and ages of all members of the household, and each subsequent census year’s schedules contain additional information on members of the household.

Each census year contains a different amount of information, with more modern census returns (also called schedules) containing the most information. Schedules from 1790 to 1840 list only the head of household for each family, along with the number of people living in the household broken down by age classifications. Schedules from 1850 on have the names and ages of all members of the household, and each subsequent census year’s schedules contain additional information on members of the household. Be careful when using these census indexes. Not all indexes include every person in the census. Some are merely head-of-household indexes. It’s a good idea to read the description that comes with the index to see how complete it is. Also, the same quality control may not be there for every census year, even within the same index-producing company. If you do not find your ancestor in one of these indexes, don’t automatically assume that he or she is not in the census. Also remember that many indexes were created outside the United States by people who were not native English speakers and who were under time constraints. It’s quite possible that the indexer was incorrect in indexing a particular entry — possibly the person you’re searching for.

Be careful when using these census indexes. Not all indexes include every person in the census. Some are merely head-of-household indexes. It’s a good idea to read the description that comes with the index to see how complete it is. Also, the same quality control may not be there for every census year, even within the same index-producing company. If you do not find your ancestor in one of these indexes, don’t automatically assume that he or she is not in the census. Also remember that many indexes were created outside the United States by people who were not native English speakers and who were under time constraints. It’s quite possible that the indexer was incorrect in indexing a particular entry — possibly the person you’re searching for. As far as a strategy for using digitized records is concerned, we like to begin with the newest record and work our way back in time. That way we can build on the information from record to record and triangulate any new information. In our case, we start with the search result for the 1940 census. Clicking on the result brings us to the record page (see

As far as a strategy for using digitized records is concerned, we like to begin with the newest record and work our way back in time. That way we can build on the information from record to record and triangulate any new information. In our case, we start with the search result for the 1940 census. Clicking on the result brings us to the record page (see