Chapter 7

Searching for That Elusive Ancestor

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Using general Internet search engines to find your ancestors

Using general Internet search engines to find your ancestors

![]() Discovering genealogy vertical search engines

Discovering genealogy vertical search engines

![]() Using compiled resources

Using compiled resources

![]() Checking out a comprehensive genealogical index

Checking out a comprehensive genealogical index

As a genealogist, you may experience sleepless nights trying to figure out all the important things in life — the maiden name of your great-great-grandmother, whether great-grandpa was really the scoundrel that other relatives say he was, and just how you’re related to Daniel Boone. (Well, isn’t everyone?) Okay, so you may not have sleepless nights, but you undoubtedly spend a significant amount of time thinking about and trying to find resources that can give you answers to these crucial questions.

In the past, finding information on individual ancestors online was like finding a needle in a haystack. You browsed through long lists of links in hopes of finding a site that contained a nugget of information to aid your search. But looking for your ancestors online has become easier than ever. Instead of merely browsing links, you can use search engines and online databases to pinpoint information on your ancestors.

This chapter covers the basics of searching for an ancestor by name, presents some good surname resource sites, and shows you how to combine several Internet resources to successfully find information on your family.

Letting Your Computer Do the Walking: Using Search Engines

Finding information on an ancestor on the web can be a challenge. In the past, it was sometimes difficult to find any kind of information about a given individual because online collections were just beginning to grow and become accessible. Now, with the myriad resources available, the challenge is sorting through all the non-relevant information to find data that can help progress your research. One of the key online resources that you can use to help locate and filter some of the online data is a search engine.

Search engines are programs that examine huge indexes of information generated by web robots, or simply bots. Bots are programs that travel throughout the Internet and collect information on the sites and resources that they find. You can access the information contained in search engines through an interface, usually through a form on a web page.

The real strength of search engines is that they allow you to search the full text of web pages instead of just the title or a brief abstract of the site. This is particularly valuable in a family history because a researcher may be looking for one of thousands of people who descended from a particular individual — for whom the web page may be named. For example, many genealogy websites are named for the progenitor of the family. In Matthew’s case, the progenitor for his branch of the Helm family was Georg Helm. A web page for this family might be named something like The Georg and Dorothea Helm Family. If Matthew is looking for one of Georg’s great-great-great grandsons, Uriah Helm, he might not know to look under the Georg Helm website to find him. Some genealogy programs create websites with thousands of pages of information, only one of which might pertain to Uriah. If a search engine bot happens to index all the pages of the site, however, Uriah’s name becomes visible through the search results.

Although search engines offer a lot of coverage of the web, to find what you’re looking for is sometimes more of an art than a science. In the following pages, we look at search strategies as well as the different kinds of search engines that are available to aid your search.

Diving into general Internet search engines

General search engines (such as Google or Bing) send out bots to catalog the Internet as a whole, regardless of the subject(s) of the site’s content. Therefore, on any given search, you’re likely to receive a lot of hits, perhaps only a few of which hold any genealogical value — that is, unless you refine your search terms to give you a better chance at receiving relevant results.

You can conduct several types of searches with most search engines. Looking at a search engine’s Help link to see the most effective way to search is always a good idea. Also, search engines often have two search interfaces — a simple search and an advanced search. With the simple search, you normally just type your query and click the Submit button. With an advanced search, you can use a variety of options to refine your search. These options can be in the form of checkboxes, or they can be the manner that you format the search terms. The best way to become familiar with using a search engine is to experiment and see what kinds of results you get.

To demonstrate various strategies for using a search engine, we run through some searches using Google for Matthew’s ancestor Georg. Before we begin the search, it’s a good idea to have some useful facts at hand to help define our search terms. From previous research, Matthew knows that Georg’s name is spelled Georg on his gravestone — but George in land records. He also knows that Georg was born in 1723 and died in 1769 and that he owned land in Winchester, Frederick County, Virginia. He was married to a woman named Dorothea.

Not all search terms are equal

When first using a search engine, a number of people simply type the name of an ancestor, expecting the search engine to take care of the rest. Although search engines do have some default ways of searching, these ways aren’t always the best for genealogical searches. The following table lists the number of results that we received with different search criteria.

|

Search Criteria |

Number of Results |

|

Georg Helm |

567,000 |

|

George Helm |

14,800,000 |

|

Georg OR George Helm |

19,400,000 |

The first search, using Georg Helm, produces hundreds of thousands of results because it looks for any content containing the words Georg and Helm. The results include not only pages that contain the name Helm but also pages containing the common word helm. Some search engines also expand the search to include variations on the spelling of the word. (This practice is common in search engines and is referred to as stemming.) The search for George Helm yields more results because the addition of the letter e in George forms a more popular first name. The third search demonstrates the capability of Google to search for multiple conditions within a single set of search terms. Placing the OR modifier in the search terms allows both Georg and George to be searched and ranked into one set of results. Searching with these dual terms generates a list that includes all the results from the first (Georg Helm) and second (George Helm) searches.

Although each of these searches produces thousands or millions of results, only a tiny fraction has anything to do with the Georg Helm that we’re looking for. So, we need to refine our search method to get a better selection of more appropriate results.

Searching with phrases

Using quotation marks in Google searches helps you specify the exact form of the word to search. Placing “Georg Helm” in quotation marks means that you want Google to search words that exactly match Georg Helm. Using parentheses indicates the search engine should look for multiple words in conjunction with other words, allowing you to search more efficiently. For example, putting parentheses around both first names with the conjunction OR tells the search engine to look for either of those first names when they appear with that last name.

Even with these modifiers on the first names, you can see that the results for “Georg” Helm and “George” Helm in the following table still number in the tens of thousands because the search engine is looking for any content that contains both the words Georg and Helm or George and Helm.

|

Search Criteria |

Number of Results |

|

(Georg OR George) Helm |

19,400,000 |

|

“(Georg OR George) Helm” |

43,500 |

Performing targeted searches

The search strategies we mention earlier in this chapter are fine for getting a general idea of what’s available for a particular name or for searching for a unique name, but they’re not necessarily the most efficient for finding information on a specific person. The best strategies involve using specific search terms that include geographic information or other family members associated with the individual.

Using the same example from earlier — searching for information about Georg Helm — we can find more targeted information on Georg Helm by including geographical terms in the search. The following search term yields 955 results:

“(Georg OR George) Helm” (Winchester OR “Frederick County”) + Virginia

The search term requires that the online content contain the following:

- The words Georg Helm or George Helm

- The word(s) Winchester or Frederick County

- The word Virginia

Of these results, less than a quarter of the results have anything to do with the Georg Helm who is the ancestor of Matthew.

Because other George Helms are associated with Frederick County, Virginia, we can further clarify the search terms to include Georg’s wife’s name — Dorothea. The following search term generates 504 results:

“(Georg OR George) Helm” (Winchester OR “Frederick County”) + Virginia Dorothea

You can also use targeted searches to meet specific research goals. For example, if Matthew is looking for the will of Georg Helm, he could use the following search terms:

“(Georg OR George) Helm” (Winchester OR “Frederick County”) + Virginia Dorothea “will”

A few other Google hints

To get the most relevant content to meet your research goals, you have a few other ways to control the results presented by Google. The first is to exclude certain results by using the – (minus) sign. In the case of Matthew’s search for George Helm, several of the results that he received in his previous searches dealt with another George Helm who was born in Frederick County, Virginia, and who is unrelated to Matthew’s Georg. This second George was married to Sarah Jackman and later moved to Cumberland County, Kentucky. To avoid seeing results for the second George, we can modify our search terms to the following:

“(Georg OR George) Helm” (Winchester OR “Frederick County”) + Virginia –Jackman –”Cumberland County”

Sometimes searching on a phrase can be too exact. If the person you’re researching is listed with a middle name, you might not find the content with a phrase search. One way around this is to use the * wildcard term. A search term such as Georg * Helm would pick up content containing the name Georg Smith Helm, as well as content containing Georg and Dorothea Helm.

You can also use number ranges within your search terms to push more relevant search results to the top of your results list. When searching within Google, you can specify number ranges by placing two periods between the range of numbers. So, if you want to search on a range of numbers from 1723 to 1769, place two periods between 1723 and 1769. For example, you could use the following search terms:

“(Georg OR George) Helm” 1723..1769

This term searches for content with Georg Helm or George Helm with a number between 1723 and 1769. In our example, this search would yield pages related to Georg Helm who died in 1769, as well as his son who was born in 1751.

Google offers a few other useful features for limiting results. If you’re searching for a relatively common name, you can try to focus your search on the page titles of content to keep from being overwhelmed by millions of results. To do this, use intitle or allintitle in your search terms. (Yes, you are seeing those correctly — do not put spaces in the phrases intitle [for in title] or allintitle [for all in title] when using them in the search term. Google knows how to interpret them without the spaces.) For example, the search term intitle:Georg Helm Dorothea looks for sites that have Georg, Helm, or Dorothea in the page title. However, the search includes even the sites that don’t have all the search terms in the title (although it scores sites that contain all three words higher than those that don’t). To search for sites that have all of the search terms in the title, use the allintitle function — allintitle:Georg Helm Dorothea.

Similarly, you can use the intext function to limit the results to search terms that appear in the text of the page. By using the search term intext:Georg Helm Dorothea (or, if you want all search terms to appear — allintext:Georg Helm Dorothea), you can search for sites with those specific words in the text of the web page. If you remember coming across a page with a link that is important to your research but can’t remember where you found it, you can use the inanchor function. A search such as inanchor:Georg Helm looks for Georg Helm in links within a page. The search modifier allinanchor looks for all the search terms within the link. And finally, if you want to look for search terms within a URL or Uniform Resource Locator (the address where information can be found and the method for retrieving it through the World Wide Web), use the inurl and allinurl search modifiers (such as inurl:Georg Helm).

Using the advanced search form

Perhaps you don’t want to use the search syntax for the search engine. Fortunately for you, most search engines offer an advanced search form, which makes your search easier. Try the following steps to use the Google advanced search:

-

Point your web browser to

https://www.google.com/advanced_search.The Advanced Search page opens with several fields that you can use to limit the search results.

-

Type your ancestor’s name (or other search term) in one of the fields in the Find pages with section.

You can put your search terms in one of the following fields. Here are some hints as to when you might use each field:

- All These Words: When the words can appear in any order or context

- This Exact Wording or Phrase: When you’re typing a name or location that needs to match the exact order

- Any of These Words: When you want Google to look for any site that might have one of many words (such as location names within a state or county)

-

Enter unwanted search terms into the field marked None of These Words.

You might want to enter terms in this field when you want to differentiate your ancestor from someone else with the same name.

-

Add information into other fields to limit your results in the Narrow Your Results By section.

On the first search, you might not want to limit your results, but the fields are there in case you do.

-

Click the Advanced Search button.

A Google results page appears.

Flying with Genealogy Vertical Search Engines

If you have used a general Internet search engine, you know that you can receive a lot of extraneous results that are unrelated to genealogy or local history. Even searching for Georg Helm produces hundreds of links about the mathematical theories of the German mathematician, Georg Helm. Although those theories might be interesting, we have only so much time to dedicate to research, and we want to use that time wisely.

One way to maximize your research time is to use a vertical genealogy search engine. A vertical search engine is a site that indexes content about a specific topic rather than attempting to index the entire web. So, in theory, the results from a genealogy vertical search engine should contain things that pertain to genealogy and local history. The challenge for the owners of vertical search engines is to ensure that the content that is indexed by the bot is consistent with the topic. That means that the maintainers of the search engine must screen the sites that are included in the index, either through the technology or by indexing only particular sites. A search engine to look at for genealogy and local history is the Genealogy Toolbox (www.genealogytoolbox.com). (In the spirit of full disclosure, we maintain the Genealogy Toolbox search engine.)

The Genealogy Toolbox has been around since 1994. It began as a list of links to genealogy and local-history resources and added a search engine in 1998. Today, the focus of the free site is on the search engine and in preformatted searches.

-

Navigate to

www.genealogytoolbox.com.The Genealogy Toolbox home page appears. Under the section labeled Genealogy Toolbox Full-Text Search is a search box.

-

Type your search terms in the search box and click the Search button.

For hints on search syntax read the information located above the search box. The search results appear, as shown in Figure 7-1.

-

Click on a link that interests you.

You can also use the preformatted searches located on the home page to reduce the amount of time spent searching. These preformatted searches appear as links in the Search Categories text box located just below the search form.

FIGURE 7-1: Search results from the Genealogy Toolbox search engine.

Finding the Site That’s Best for You

Your dream as an online genealogist is to find a website that contains all the information that you ever wanted to know about your family. Unfortunately, these sites simply don’t exist. However, during your search, you may discover a variety of sites that vary greatly in the amount and quality of genealogical information. Before you get too deep into your research, it’s a good idea to look at the type of sites that you’re likely to encounter.

Personal genealogical sites

The majority of non-subscription pages that you encounter on the web are maintained by an individual who is interested in researching a particular person or family line. These pages usually contain information on the site maintainer’s ancestry or on particular branches of several different families rather than on a surname as a whole. That doesn’t mean valuable information isn’t present on these sites — it’s just that they have a more personal focus.

You can find a wide variety of information on personal genealogical sites. Some pages list only a few surnames that the maintainer is researching; others contain extensive online genealogical databases and narratives. A site’s content depends on the amount of research, time, and computer skills the maintainer possesses. Some common items that you see on most sites include a list of surnames, an online genealogical database, pedigree and descendant charts, family photographs, research blogs, and the obligatory list of the maintainer’s favorite genealogical Internet links.

An example of a personal genealogical site is the Rubi-Lopez Genealogy Page (http://rubifamilygen.com), shown in Figure 7-2. The Rubi-Lopez page contains articles on different lines of the family, a photo gallery, and links to other family websites.

FIGURE 7-2: The Rubi-Lopez Genealogy Page is an example of a personal genealogy site.

One-name study sites

If you’re looking for a wide range of information on one particular surname, a one-name study site may be worth your while. These sites usually focus on one surname regardless of the geographic location where the surname appears. In other words, they welcome information about people with the surname worldwide. These sites are quite helpful because they contain all sorts of information about the surname, even if they don’t have specific information about your branch of a family with that surname. Frequently they have information on the variations in spelling, origins, history, DNA, and heraldry of the surname. One-name studies have some of the same resources you find in personal genealogical sites, including online genealogy databases and narratives.

Although one-name study sites welcome all surname information regardless of geographic location, the information presented at one-name study sites is often organized around geographic lines. For example, a one-name study site may categorize all the information about people with the surname by continent or country — such as Helms in the United States, England, Canada, Europe, and Africa. Or, the site may be even more specific and categorize information by state, province, county, or parish. You’re better off if you have a general idea of where your family originated or migrated from. But if you don’t know, browsing through the site may lead to some useful information.

The Rowberry One-Name Study website (http://www.rowberry.org/) is a one-name study site with several resources for the Rowberry, Rowbury, Ruberry, Rubery, Rewbury, Robery, Roebury, Rovery, Rowbery, Rowbory, Rowbree, Rowbrey, Rowburrey, Rubbery, Rubbra, Rubra, Rubrey, and Rubury surnames. From the home page (see Figure 7-3), you can choose to view news on recent additions to the site, articles on current discoveries, results of the surname DNA project, research in different countries, and information on how to join a mailing list of the surnames.

FIGURE 7-3: The Rowberry One-Name Study website.

To find one-name study sites pertaining to the surnames you’re researching, you have to go elsewhere. Where, you ask? One site that can help you is the Guild of One-Name Studies (www.one-name.org).

Gee, we bet you can’t figure out what the Guild of One-Name Studies is! It’s exactly as it sounds — an online organization of registered sites, each of which focuses on one particular surname. Follow these steps to find out whether any of the Guild’s members focus on the surname of the person you’re researching:

-

Open your web browser and go to

www.one-name.org.The home page appears with a search field just below the title of the site.

- Type the surname you’re researching in the field entitled Is Your Surname Registered?

-

Click the Search button.

If a registered one-name study is available, you see links to the study’s website and, if available, DNA website.

Family associations and organizations

Family association sites are similar to one-name study sites in terms of content, but they usually have an organizational structure (such as a formal association, society, or club) backing them. The association may focus on the surname as a whole or just one branch of a family. The goals for the family association site may differ from those for a one-name study. The maintainers may be creating a family history in book form or a database of all individuals descended from a particular person. Some sites may require you to join the association before you can fully participate in their activities, but this is usually at a minimal cost or free.

The Wingfield Family Society site (www.wingfield.org), shown in Figure 7-4, has several items that are common to family association sites. The site’s contents include a family history, newsletter subscription details, a membership form, queries, mailing list information, results of a DNA project, and a directory of the society’s members who are online. Some of the resources at the Wingfield Family Society site require you to be a member of the society to access them.

FIGURE 7-4: The Wingfield Family Society site.

To find a family association website, your best bet is to use a search engine. For more on search engines, see the section “Diving into general Internet search engines,” earlier in this chapter. Be sure to use search terms that include the surname you’re interested in researching and one of these keywords: society, association, group, or organization.

Surnames connected to events or places

Another place where you may discover surnames is a site that has a collection of names connected with an event or geographic location. The level of information available on these sites varies greatly among sites and among surnames on the same site. Often, the people who maintain such sites include more information about their personal research interests than other surnames, simply because they have more information on their own lines.

Typically, you need to know events that your ancestors were involved in or geographic areas where they lived to use these sites effectively. Also, you benefit from the site simply because you have a general, historical interest in the event or location, even if the website contains nothing on your surname. Finding websites about events is easiest if you use a search engine, a comprehensive website, or a subscription database. Because we devote an entire chapter to researching geographic locations (Chapter 6), we won’t delve into that here.

Family Trees Ripe for the Picking: Finding Compiled Resources

Using online databases to pick pieces of genealogical fruit is wonderful. But you want more, right? Not satisfied with just having basic obituary information on his great-grandfather, Matthew is eager to know more — in particular, he’d like to know who William Henry Abell’s grandfather was. You have a few research tactics to explore at this point. Perhaps the first is to see whether someone has already completed some research on William Henry Abell and his ancestors.

When someone publishes his or her genealogical findings (whether online or in print), the resulting work is called a compiled genealogy.

Compiled genealogies can give you a lot of information about your ancestors in a nice, neat format. When you find one with information relevant to your family, you get an overwhelming feeling of instantaneous gratification. Wait! Don’t get too excited yet! When you use compiled genealogies, it’s important to remember that you need to verify any information in them that you’re adding to your own findings. Even when sources are cited, it’s wise to get your own copies of the actual sources to ensure that the author’s interpretation of the sources was correct and that no other errors occurred in the publication of the compiled genealogy.

Compiled genealogies take two shapes online. One is the traditional narrative format — the kind of thing that you typically see in a book at the library. The second is in the form of information exported from an individual’s genealogical database and posted online in a lineage-linked format (lineage-linked means that the database is organized by the relationships between people).

Narrative compiled genealogies

Narrative compiled genealogies usually have more substance than their exported database counterparts. Authors sometimes add color to the narratives by including local history and other text and facts that can help researchers get an idea of the time in which the ancestor lived. An excellent example of a narrative genealogy is found at The Carpenters of Carpenter’s Station, Kentucky, at http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~carpenter.

The site maintainer, Kathleen Carpenter, has posted a copy of her mother’s historical manuscript on the Carpenter family, as well as some photos and a map of Carpenter’s Station. You can view the documents directly through the web or download PDF copies.

To locate narrative genealogies, try using a search engine or comprehensive genealogical index. (For more information on using these resources, see the sections later in this chapter.) Often, compiled genealogies are part of a personal or family association website.

You can also find a collection of family histories at the Family History Books portion of FamilySearch (https://books.familysearch.org/primo_library/libweb/action/search.do?dscnt=1&vid=FHD_PUBLIC&). Just type the name that interests you in the search form to see whether a compiled genealogy has been placed online.

Compiled genealogical databases

Although many people don’t think of lineage-linked, online genealogical databases as compiled genealogies, these databases serve the same role as narrative compiled genealogies — they show the results of someone’s research in a neatly organized, printed format.

For example, the Simpson History site (http://simpsonhistory.com/_main_page.html) is a personal site that contains a compiled genealogical database providing information on John “The Scotsman” Simpson and his descendants. You can navigate through descendant charts and family group sheets, clicking particular individuals to access more information about them.

Finding information in compiled genealogical databases can sometimes be tough. There isn’t a grand database that indexes all the individual databases available online. Although general Internet search engines have indexed quite a few, some very large collections are still accessible only through a database search — something that general Internet search engines don’t normally do.

In the preceding section, we conducted a search on Matthew’s great-grandfather, William Henry Abell. Now we want to find out more about his ancestry. We can jump-start our research by using a lineage-linked database in hopes of finding some information compiled from other researchers that can help us discover who his ancestors were (perhaps even several generations’ worth). From documents such as his obituary and death certificates, we find out that William Henry Abell’s father was named Samuel Abell and his mother was named Martha Susan Baird. And from research, we also know that Samuel Abell was living in Larue County, Kentucky, in the early 1870s. Armed with this information, we can search a compiled genealogical database.

The FamilySearch Internet Genealogy Service (www.familysearch.org) is the official research site for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS). This free website allows you to search several LDS databases including the Ancestral File, International Genealogical Index, Pedigree Resource File, vital records index, census records, and a collection of abstracted websites — all of which are free. The two resources that function much like lineage-linked databases are the Ancestral File and the Pedigree Resource File. Fortunately, you don’t have to search each of these resources separately. A master search is available that allows you to search all of the resources on the site at once. See Chapter 3 for more on how to use the FamilySearch site.

You can find several other lineage-linked collections that may contain useful information. The following list gives you details on some of the better-known collections:

- Ancestry Family Tree: The Ancestry.com site (

http://search.ancestry.com/search/db.aspx?dbid=1030) contains a free area where researchers can search through the files of other researchers. - WorldConnect: The WorldConnect Project (

http://wc.rootsweb.ancestry.com/) is part of the RootsWeb.com site. The Project has more than 800 million names in its database. - MyTrees.com: MyTrees.com (

www.mytrees.com) is a site maintained by Kindred Konnections. The site has a lineage-linked database available only by subscription. - OneGreatFamily.com: OneGreatFamily.com (

www.onegreatfamily.com/Home.aspx) hosts a subscription-based, lineage-linked database. - Geni: Geni (

www.geni.com) a site owned by MyHeritage, hosts a free database with subscription-based add-on features. - WikiTree: WikiTree (

www.wikitree.com) is a free site for creating and searching family trees focused on collaboration.

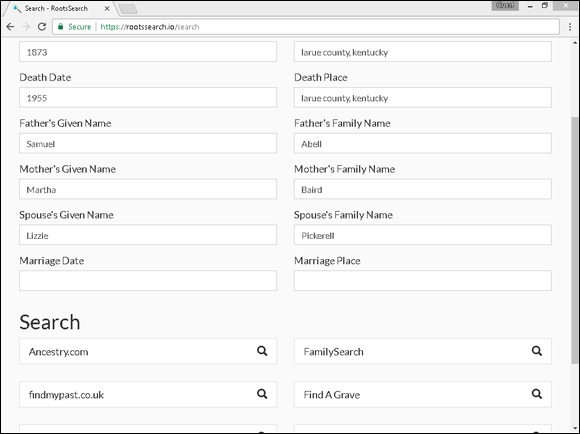

RootsSearch (https://www.rootssearch.io) is a tool for searching through multiple sites using the same search interface. It is available as an extension to the Google Chrome web browser and supports searching of over 20 genealogically focused sites. It does not search all of the sites at the same time; rather, it allows you to enter the information once and then select a site to search (see Figure 7-5).

FIGURE 7-5: The RootsSearch search form.

Browsing Comprehensive Genealogical Indexes

If you’re unable to find information on your ancestor through a search engine or online database, or if you’re looking for additional information, another resource to try is a comprehensive genealogical index. A comprehensive genealogical index is a site that contains a categorized listing of links to online resources for family history research. Comprehensive genealogical indexes can be organized in a variety of ways, including by subject, alphabetically, or by resource type. No matter how the links are organized, they usually appear hierarchically — you click your way down from category to subcategory until you find the link for which you’re looking.

Some examples of comprehensive genealogical indexes include the following:

- Cyndi’s List of Genealogy Sites on the Internet:

www.cyndislist.com - Linkpendium:

www.linkpendium.com

To give you an idea of how comprehensive genealogical indexes work, try the following example:

-

Fire up your browser and go to Linkpendium (

www.linkpendium.com).This step launches the home page for Linkpendium.

- Scroll down to the portion of the main page with the links to surnames.

-

Click a link with a letter for your surname.

For example, we’re looking for Abell, so we click the A surnames link.

-

Click the link that contains the first three letters of the surname you’re researching.

We click the link entitled Abe Families.

-

Click the link to your surname.

We click the Abell Family: Surname Genealogy, Family History, Family Tree, Family Crest link. Figure 7-6 shows the links for the Helm surname.

FIGURE 7-6: Looking for Abell resources on Linkpendium.

One drawback to comprehensive genealogical indexes is that they can be time-consuming to browse. It sometimes takes several clicks to get down to the area where you believe links that interest you may be located. And, after several clicks, you may find that no relevant links are in that area. This lack may be because the maintainer of the site has not yet indexed a relevant site or the site may be listed somewhere else in the index.

Personal genealogical sites vary not only in content but also in presentation. Some sites are neatly constructed and use plain backgrounds and aesthetically pleasing colors. Other sites, however, require you to bring out your sunglasses to tone down the fluorescent colors, or they use lots of moving graphics and banner advertisements that take up valuable space and make it difficult to navigate through the site. You should also be aware that the JavaScript, music players, and animated icons that some personal sites use can significantly increase your download times.

Personal genealogical sites vary not only in content but also in presentation. Some sites are neatly constructed and use plain backgrounds and aesthetically pleasing colors. Other sites, however, require you to bring out your sunglasses to tone down the fluorescent colors, or they use lots of moving graphics and banner advertisements that take up valuable space and make it difficult to navigate through the site. You should also be aware that the JavaScript, music players, and animated icons that some personal sites use can significantly increase your download times. The maintainers of one-name study sites welcome any information you have on the surname. These sites are often a good place to join research groups that can be instrumental in assisting your personal genealogical effort.

The maintainers of one-name study sites welcome any information you have on the surname. These sites are often a good place to join research groups that can be instrumental in assisting your personal genealogical effort.