The X Files: Don’t Fight the Future

The Truth Is Out There!

Art, not matter how you produce it, requires tools and in this new millennium, the favorite tool for many artists is the computer. While it is hardware that makes it possible to create digital graphics, it is the software that enables the artist to harness the computer’s energy and create illustrations, photographs, and drawings.

Don’t let lost in the matrix of confusing image file acronyms. In this chapter, we’ll take a look at everything you need to know working with digital imaging file formats. ©2004 Joe Farace.

To those computer users who don’t work with graphics software on a regular basis the difference between programs such as Adobe Photoshop and Macromedia FreeHand (www.macromedia.com) may not seem significant. While digital designers use both programs to create art, that’s the only aspect that Paint and Draw programs have in common. The real difference between these two different kinds of software boils down to the fact that Paint programs, such as Photoshop, work with bitmapped images, while Draw software, like FreeHand, works with vector-based images. Which brings up the question: Why do we need different kinds of graphics software anyway?

The Ipcress Files

There are three basic classes of graphic image files: bitmap, metafile, and vector. A bitmap (sometimes called “raster”) file is made up of a collection of individual pixels—one for every point on a computer screen. The simplest 1-bit files are monochrome images and are composed of a single color against a background. Images that display more shades of color or gray need more than one bit to define those colors. In fact, the more bits the merrier and the more colors that can be displayed and manipulated.

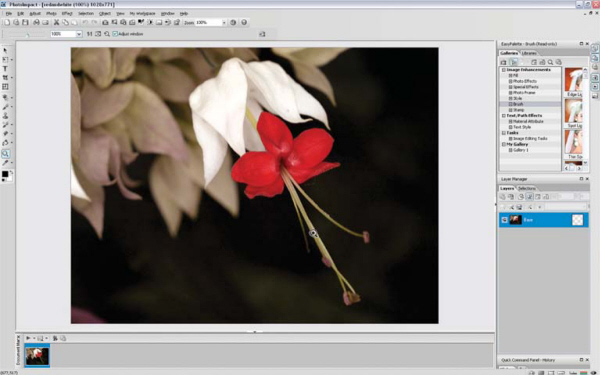

Paint software, such as Adobe Photoshop and Ulead’s PhotoImpact (www.ulead.com), all work with bitmapped image files.

Graphics saved in vector formats are stored as points, lines, and mathematical formulae that describe the shapes that make up a drawing. That’s why photographs are not typically saved in this format. When vector files are viewed on your computer screen or printed, these formulae are converted into a dot pattern and displayed (or printed) as bitmapped graphics. Since all of the pixels that you see are not part of the file itself, the file can be resized without losing image quality. Some computer users call vector-format files “object-oriented,” and you often see this term used in conjunction with drawing programs such as Adobe Illustrator.

A metafile is a multifunction graphic file type that accommodates both vector and bitmapped data within the same format. While seemingly more popular in the Microsoft Windows environment, Apple Computer’s old standby PICT format is a metafile. Many kinds of graphics program will work with metafiles.

I am a Camera

When talking about digital image files you’ll first meet the word compression. Data compression enables devices to capture or store the same amount of data in fewer bits. It does this by discarding colors that may not be visible to the eye, but how well it does this ultimately determines image quality. All digicams use some kind of compression techniques to store images. The greater the compression ratio, the greater loss of quality you can expect. Lower compression produces fewer, better quality images. The highest image quality option is “no compression” or the Tagged Image File Format (TIFF) and RAW format many digital SLRs offer.

Joint Photographic Experts Group (JPEG) is an acronym for a compressed graphics format created by the JPEG (www.jpeg.org) within the International Standards Organization. (Because of the three-letter suffix convention used by Windows-based computers, this is often shortened to JPG.) All digicams use some kind of JPEG compression to store images. JPEG techniques compress an image file into discrete blocks of pixels, which are divided in half using ratios varying from 10:1 to 100:1. The higher the ratio, the greater quality loss you can expect. Lower compression produces fewer, better quality images. The highest image quality option is “no compression.”

JPEG 2000 | |

Not currently an in-camera option on any digital camera that I know of (but who knows what might hit the market by the time you read this) JPEG 2000 uses wavelet technology for greater data compression while offering better image quality than JPEG. Wavelet algorithms process data at different scales or resolutions. (For more information about wavelets, visit www.amara.com/current/wavelet.html) Often less than 1% of the original data size is required for “very good” representation of your original image, making for small files with little data loss. | TIFF is a bitmapped file format originally developed by Microsoft (www.microsoft.com) and Aldus. A TIFF file (.TIF is used in Windows) can be any resolution from black and white up to 24-bit color. TIFFs are platform-independent files, so that files created on your Mac OS computer can (almost) always be read by a Windows graphics program. Some digital cameras, such as the Olympus E-500, let you capture directly in TIFF format. The upside: No processing is required. The downside: The files are always larger than RAW (more on RAW next) because they will white balance and other data. |

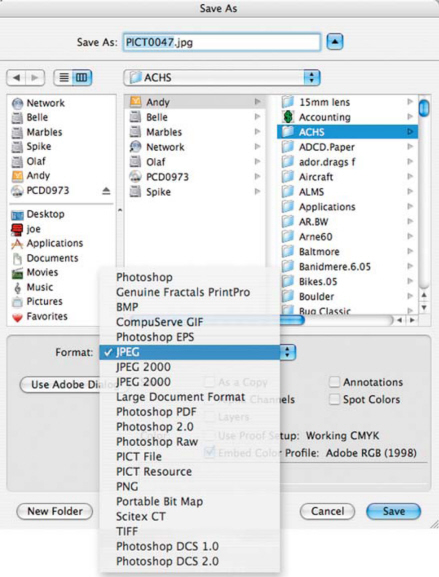

When you save a file in JPEG 2000 format using Adobe Photoshop CS2, this is what the Dialog box that appears looks like. Even if you’ve never used this file format before the controls and sliders that are used are self-explanatory, but you may have to manually install the JPEG 2000 plug-in in Photoshop’s File Format folder because it is not part of the standard installation. © Joe Farace.

RAW files are the naked files themselves unaffected by anything other than your ISO setting. If you like you can think of them as a negative that needs to be processed and turned into the final photograph. RAW files contain all of the original data—the good, the bad, and the ugly—so you’re gonna need some processing software to bring to the RAW file format. Even if you think you know everything you want to know about RAW capture, you might want to, at least, skim these chapters for some tips. If, on | the final image that was lurking inside that original capture to fruition. For some beginners, there is some confusion about what RAW files are, how they work along with when, where and why you should use this form of image capture. That’s why the next two chapters are dedicated specifically the other hand, you want to increase you awareness of the advantages and techniques associated with RAW file format capture, you might want to read them in more detail. |

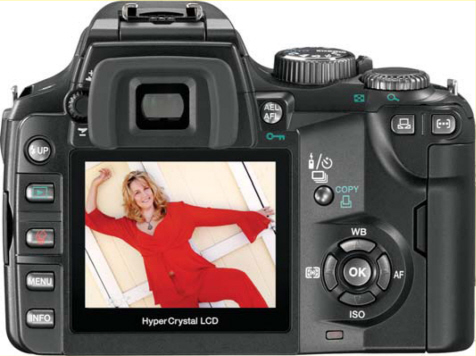

The versatile Olympus E-500 digital SLT lets you capture images in JPEG, RAW, and TIFF file formats Inset photo: © Mary Farace.

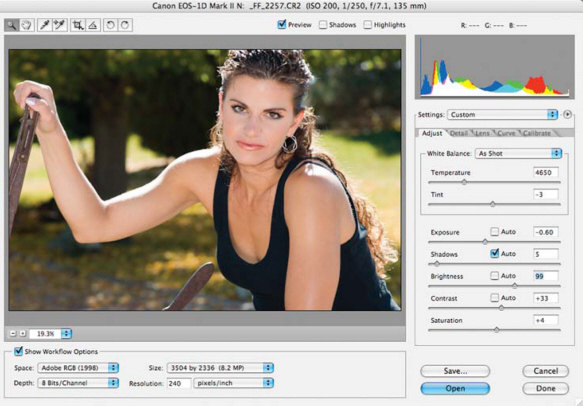

While the camera manufacturer’s software continues to improve, the main reason I started using RAW capture on a routine basis was the availability of Adobe’s Camera RAW. © 2005 Joe Farace.

The Gang That Couldnd’t Shoot Straight

There is some loss of quality when JPEG files are captured but you can get more files per memory card with compressed images. Higher capacity memory cards are getting less expensive, but the last time I checked nobody was giving them away. RAW or TIFF files deliver the ultimate image quality from your digital camera, but you’ll need to buy more and bigger memory cards.

So the big question remains is how to shoot’em but the answer ultimately is tied to how are you gonna use’em. If you just want a bunch of 4 × 6 prints of your vacation or some snapshots to e-mail to Aunt Midge, JPEG files will deliver what you need. If you are going to Yosemite to shoot images that you want to sell in art galleries or as stock images, shooting RAW just makes more sense. If working on images with computers is not your cup of tea, think about using TIFF, if your camera has that option.

The real question is “how much resolution do you need?” The ultimate test for image quality should be based on how a photograph is used and viewed. Once again, real-world comparisons are called for. A photograph made with the finest grain film and highest quality lens throws away most of its resolution when it is printed in a newspaper. Yet, the average person will find it difficult to tell the difference between a conventional 4 × 6-inch color print and an image made with a digital camera and printed on 4 × 6 Photo Paper by any inexpensive photo quality ink-jet paper. All of the above equipment is moderately priced, yet the results are truly photographic. This challenge introduces yet another variable—the experience of the viewer—into consideration when evaluating the quality of any photographic image.

What do I do? (In case anybody is interested.) Most of the time I shoot JPEG files event for publication, but that’s based on shooting the 8.2 megapixel (3504 × 2336) images files that are possible with my Canon EOS 1D Mark II.

Like the EOS 1D Mark II, the N model has separate slots for Compact Flash and SD memory cards but adds a unique twist. It’s now possible to record RAW image onto one memory card, and JPEGs on the other. This means you can capture color RAW files on the CompactFlash card, while recording JPEG files in toned monochrome on the SD card at the same time! It’s also easy to switch between card slots. Just press the Card Select button to display a card selection screen.

This photograph of a Nissan Skyline was part of an assignment for Modified magazine. The Art Director’s instructions were that I shoot large JPEG files for everything except those images that might be used across two pages. These, he asked, be shot as RAW. I shot everything as a JPEG file and this image ended up being spread across two pages and looked pretty good. Image captured with a Canon EOS 1D Mark II and 75–300mm zoom lens. Exposure was 1/800th of a second at f/11 at ISO 200. © 2004 Joe Farace.

This portrait of Jamie Lynn was made with an EOS 1D Mark IIN and was captured in RAW mode on the camera’s CompactFlash card. Exposure was 1/200th of a second at f/5.6 at ISO 200. © 2005 Joe Farace.

Buried in the EOS 1D Mark IIN menu is a set of “Picture Styles”—not modes—that includes six presets including, Standard, Portrait, Landscape, Neutral, Faithful, and Monochrome. You can further add digital filters and even tone the captured image—all in camera. Using the cameras built-in back-up mode I was able to simultaneously capture a full color RAW file as well as this digitally filtered and tined monochrome shot. © 2005 Joe Farace.

Crossing Delancey

Regardless of what kind of operating system you use on, sooner or later there will come a day when someone will hand you a disc containing files designed for that “other” computer system. If you have the right tools, dealing with incompatible file formats doesn’t have to cause you any distress. As you will soon discover, translating graphic file formats and moving files back and forth between Mac OS and Windows platforms is a lot easier than you might think.

Part of the problem of any kind of image conversion is that digital photographs come on an often-bewildering variety of file types. You will find them saved as PICT, TIFF, Windows Bitmap (BMP), PCX, and PCD along with some file types unique to Mac OS or Windows. Understanding what a particular file format’s acronym means can take some of the stress out of the conversion process. Appendix A contains some of the computer acronyms, buzzwords, and terms you often find being tossed around when discussing computer graphics.

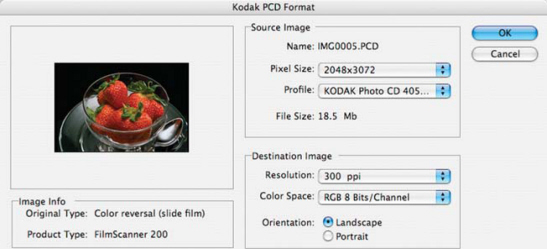

Kodak’s Photo CD format was the closest thing yet to a Rosetta Stone for image interchangeability. Any Mac OS or Windows program that’s compatible with the PCD format can read all of the image files that are stored on a Photo CD disc.

Kodak’s Photo CD disc is compatible with both Mac OS and Windows platforms, but life is never that simple. Every time a hardware product or graphics software package is announced, the publisher feels obligated to create a new file format. When Apple Computer introduced their QuickTake digital camera, they also announced a brand new graphics file format just for the camera. Compounding the file conversion process is the fact that not all software programs write an existing file format in exactly the same way, producing variations or “flavors” of the so-called standard. For example, there are at least thirty-two variations of the TIFF format alone.

Adobe Photoshop is as close to a universal graphics file conversion program as there is, but when you run across a file you cannot open, it’s time to reach for specialized file translation software.

When moving graphic files back and forth between Mac OS and Windows computers, the first tool you will need is software that allows your computer to read (or mount) disks formatted for the “other” machine. Luckily, Mac OS users already have what they need. Apple Computer’s operating system lets it read any kind of Windows-formatted media you can throw at it.

On the Windows side of the disc/disk compatibility issue, DataViz’s (www.dataviz.com) MacOpener is the best utility of its kind that I have ever found for Windows computers. MacOpener lets Window users use Mac OS floppy disks, CD-ROM discs, as well as removable media cartridges. When working with cross-platform programs like QuarkXPress, Adobe PageMaker and Photoshop, life has never been better or simpler. This is the best one hundred bucks any Windows user interested in file conversion can spend.

DataViz’s Conversions Plus lets Window users use Mac OS floppy disks, CD-ROM discs, as well as removable media cartridges.

Lost in Translation

Once you have the capability to read media from other computers, the next part of your translation quest involves using the proper file conversion software. The type of file translation software you will need is based on your personal requirements. Are they average or heavy duty? If your file translation needs are only occasional, here’s all the software you may ever need.

Mac OS users should get a copy of DataViz’s MacLinkPlus that will translate Windows to Mac OS and Mac OS to Windows. In addition to converting graphics files, the package also translates word processing files. DataViz claims the latest version of MacLinkPlus supports more than 550 file translation combinations, and many of them are word processing, database, and spreadsheet formats. For Windows computers, DataViz offers Conversion Plus, which contains thousands of file translation options and even includes Mac Opener. The package also includes a copy of DataViz’s e-ttachment Opener, a utility that solves problems that occur when you receive attached files as e-mail. This WYSIWYG utility lets you view and print almost any kind of file—even if you don’t have the program that created it.

One of my favorite general-purpose Windows-only programs for graphic file translation is Corel’s (www.corel.com) Paint Shop Pro XI.

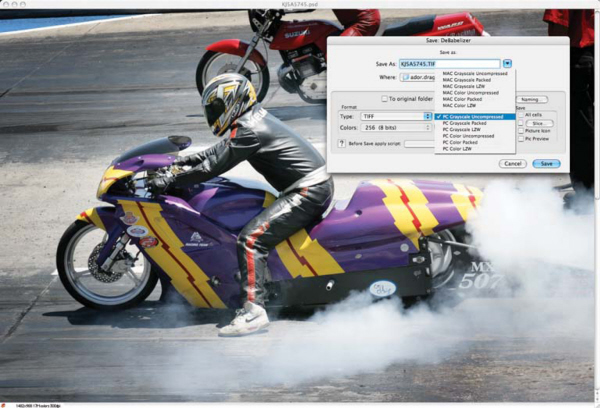

When the file conversion process gets tough, I reach for DeBabelizer Pro for the Mac OS or Windows. There is not a file type that I know of that this program cannot open and convert. When you have a group of files to convert, you can collect them into a batch and write a script to convert them as a group. If you are squeamish about doing your own scripting, don’t be. The program’s “Watch Me” command lets you go through the steps of converting a single file and automatically creates a script based on what you do. The program also includes a series of scripts that can be used to automatically process, filter, and color adjust World Wide Web-oriented graphics. Output can be delivered as GIF or JPEG files that have an optimized color palette for speedier viewing. For the average user Equilibrium DeBabelizer Pro LE is a low-cost introduction to DeBabelizer and supports 100 Web, print, multimedia, and legacy formats such as TGA (Targa.) DeBabelizer LE provides home digital imaging enthusiasts and business users access to professional image optimization and conversion tools and can be ordered online at DigitalRiver.com for $99.95.

When the file conversion process gets tough, I reach for DeBabelizer Pro for the Mac OS or Windows. There is not a file type that I know of that this program cannot open and covert. ©2005 Joe Farace.

One reference book that I’ve found to be indispensable for people who must translate graphic files from one platform to another: “The Encyclopedia of Graphics File Formats,” published by O’Reilly & Associates (www.oreilly.com) contains detailed descriptions of the different kinds of graphics file formats used by Mac OS, Windows, and UNIX computers. Some of the explanations may be too detailed for the average user, but you can use what you need and ignore what you don’t. A CD-ROM includes vendor file format specifications, graphics test images, coding examples, and graphics conversion and manipulation software.

All of the programs I have mentioned easily handled the many different graphics files I threw at them, but none of them are perfect. The last time I counted, there were more than 100 different graphics file formats for Mac OS, Windows, and UNIX and no single program translates all them. Most Windows-based translation programs are biased in favor of converting DOS and Windows formats than Mac OS files, and the same is true of Mac OS conversion programs. The only solution for seemingly impossible file conversions may be to obtain the original, creating application and save the file in a more “portable” format. As a last resort, you can take the file to a service bureau, and for a modest fee, they may be able to convert it into a usable format.

The reality of file conversion is that, like everything else in computing, some file translations are easy and some aren’t. The best way to increase your file translation skill is practice, practice, and practice. When you get stuck, go back and make sure you understand the basic principles before trying to pound a square file onto a round disk.

Revenge of the Sith

In 1839, Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre introduced photography, as we know it, to the world. The reaction of popular media of the day to the daguerreotype was that “from this day forward, painting is dead.” Obviously this didn’t happen. Just as conventional photography didn’t kill painting, digital cameras won’t kill silver-based photography either. What photography did do—and what digital imaging is doing—is to replace another medium in certain applications.

To create this faux cyanotype I photographed Lorie using only the window light coming through my back door. (The Cyanotype was invented by Sir John Herschel in 1842 and was the first successful non-silver photographic printing process. It’s blue, hence the name.) Image was captured directly in monochrome using the Canon’s EOS 30D blue toning capabilities. Exposure was 1/125th of a second at f/2.8 at ISO 320. Camera was in Shutter Priority mode and deliberately underexposed by one-third stop to increase shadows and blue saturation. ©2006 Joe Farace.

Film—especially color film—is not inherently more archivally stable than any other media. There are many variables that affect the stability of silver-based images including the age of the original film before it was exposed, how is was stored before processing, how it is processed, the freshness of the chemistry used in processing, and how is it stored after being processed. Any miscues in any one of those steps will have an effect of the long-term stability of the images. It is true that black and white film can be handled from start to finish using materials and processes that guarantee archival quality, but because of the inherent instability of the dyes used in color film. It is much more difficult to do when working with color images. The stability of some color films, notably Eastman Kodak’s Kodachrome family of transparency films, is better than the company’s other color film stock.

Like it or not, the digital genie is out of the bottle. Despite the faults, problems and missteps, companies are making with the way new digital cameras are brought to market; there is no turning back. Many users simply do not require the permanence of film, and prefer the speed and convenience of digital cameras. As I wrote in ComputerUSER a long time ago, every change in imaging technology—from the Daguerreotype to the ill-fated Advanced Photo System—has been one of convenience, not of quality. Far from being toys, digital cameras expand the democratization of photography like no technology ever before. For any neo-Luddites reading this, I have four words of advice: “Get used to it.”