CHAPTER OVERVIEW

Concepts populate the language of any job or profession. Therefore, teaching concepts effectively is a critical goal of any instructional program. If learners fail to understand important work concepts, they will be unable to perform tasks effectively. In this chapter we summarize the following instructional methods needed to teach concepts: definitions, examples, counterexamples, and analogies. We present research, psychological rationale, and examples to support the following guidelines on ways to visualize concepts:

Display two or more representational graphic examples contiguous to each other and to text definitions

Create a counterexample to help the learner build an accurate mental model

Use visual analogies especially for more abstract or unfamiliar concepts

Display related concepts together applying the contiguity principle

Use organizational graphics to illustrate related concepts and their features

Promote learner engagement with concept visuals

The ability to psychologically represent and communicate with concepts is a unique and powerful human capability that we often do not fully appreciate. Through language based on conceptual mental models we can use a few words to generalize to a universe of instances. At twelve months baby Joshua started to show concept acquisition! His mother had been teaching him sign language. He could soon point to most any common animal whether represented in a book, on his nursery wallpaper, in animal crackers or in real life and make the sign for that animal. His ability to apply a concept like fish to such diverse representations preceded his ability to talk and shows how early human concept acquisition and generalization start!

A concept is a category of objects or ideas that is usually designated by a single word. Chair is an example. As categories, concept groups include a variety of individual instances. For example metal folding chairs, office chairs, and wheelchairs fall into the concept class of chair. Each member of a concept group exhibits features common to the concept class as well as unique features. For example, most members of the chair category possess a seat, a back, and some type of support to the floor. Individual members of the group vary on features such as size, color, presence of arms, and type of support to the floor.

When learning new job skills, there are invariably several new concepts associated with them. These concepts are what make up the backbone of the language unique to the job or profession. For example, when working in Excel to copy a formula, some relevant concepts include formula, relative cell reference, and absolute cell reference. In a course on designing Web pages some concepts include image file formats, URL, and text formatting options.

When a new concept is learned, the resulting mental model in long-term memory allows the worker to discriminate new instances of the concept even though they may not have seen exactly that example. For example, once mental models of the concepts of formula and absolute versus relative cell references are acquired, the Excel user will be able to apply those concepts to any spreadsheet work they are doing.

Concepts such as chair are concrete. They have parts and boundaries and individual instances can be shown with representational visuals. In contrast, some concepts such as integrity and defect are more abstract. Often a short scenario is used to illustrate abstract concepts. For example, a scenario for integrity might be "Some Enron executives might have shown a lack of integrity in approving misleading accounting practices in order to inflate stock values" Also analogies are especially useful to communicate the meaning of abstract concepts.

Sometimes job tasks require the worker to discriminate between two or more closely related concepts. Some examples are defect versus defective, serif versus sans serif font types, or relative versus absolute cell references in Excel. Concepts like these that are related in a parallel manner are called coordinate concepts. Additionally, concepts may be hierarchically related with some concepts subordinate to others. For example, the concept of URL has the following subordinate concepts: protocol, domain, and path. Each of the three subordinate concepts is a coordinate concept.

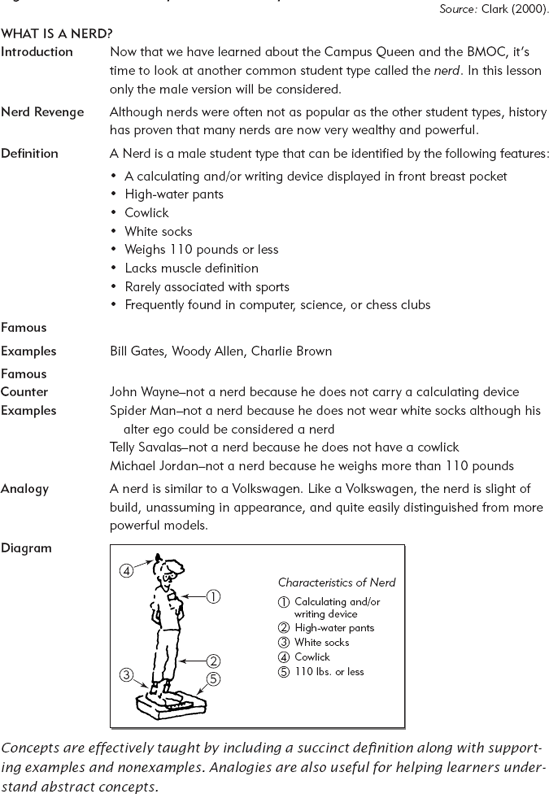

Clark (2000) summarizes guidelines derived from many years of research on how to teach concepts. Figure 12.1 shows a workbook page designed to teach the concept of nerd. As in this example you can help learners build concept mental models by providing: (1) a short definition that itemizes the key features of the concept class, (2) two or more examples of the concept, (3) one or more counterexamples when there is a closely related concept that might be confused with the lesson concept, and (4) analogies that link a new concept to familiar knowledge. A succinct definition plus at least two examples are minimal requirements to help learners build an effective mental model. Use several examples to teach more complex concepts. Additionally, use counterexamples for contrast and analogies to explain abstract concepts.

To help learners build an effective concept mental model, create practice exercises that require them to identify instances of the concept not shown during the lesson. Once they can identify new instances not seen before, you know that your learners have acquired a generalizable mental model of the concept. For example, an exercise might display several type fonts and ask the learner to identify those that are serif. Alternatively, an exercise might show the results of formulas copied into a spreadsheet and ask learners to distinguish whether the formulas used relative or absolute cell references.

To manage cognitive load, its a good idea to teach relevant concepts as separate lesson topics prior to teaching the tasks where they are used. Mayer, Mathias, and Wetzell (2002) found that students learned a lesson on how mechanical brakes worked most effectively when the lesson started with concept topics that described each component of the braking system. Each concept topic named the part and showed the different ways that the part could move. That way, when learners were exposed to the full system with all of its interactive parts, they were able to assimilate the information without overload.

In this section we describe six guidelines that suggest ways to effectively use visuals to help learners build effective concept mental models.

As mentioned previously, examples are a key instructional method to teach concepts. In fact, when given a choice between learning from a textual description of a concept or an example, learners usually select the example. (Anderson, Farrell, and Sauers, 1984; LeFevre and Dixon, 1986). Since your goal is to help learners build a mental model that will transfer to diverse new instances of the concept, it will be important to provide two or more examples. You should select examples that reflect the key features of the concept class and at the same time vary other features that are not essential distinguishing characteristics. To get the most from these examples be sure to place them adjacent to each other and to the concept definition. This is another application of the contiguity principle that specifies which instructional elements should be placed near one another on the page or screen.

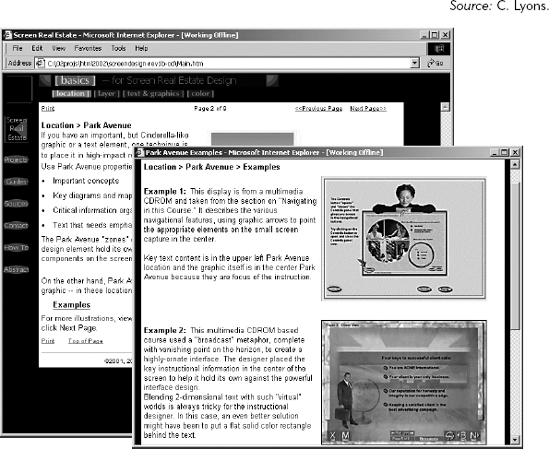

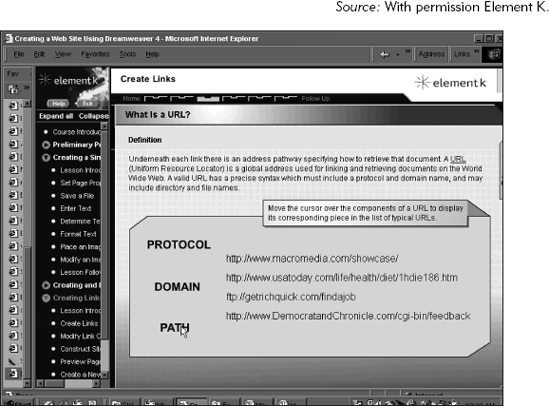

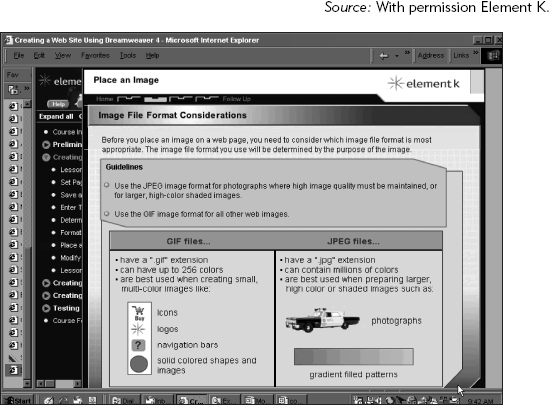

For example, Figure 12.2 includes two examples used to illustrate the concept of prime screen real estate areas. Complex concepts benefit from more examples. Figure 12.3 shows four URL examples placed under the definition. Figure 12.4 includes definitions and several visual examples of two common file formats: GIF and JPEG.

A counterexample, also known as a nonexample, is often useful to help the learner build a clear mental model of a new concept. Counterexamples are especially useful to avoid confusion that occurs when a new concept could be confused with closely related concepts. The counter example helps the learner sharpen her understanding by seeing what the concept is not.

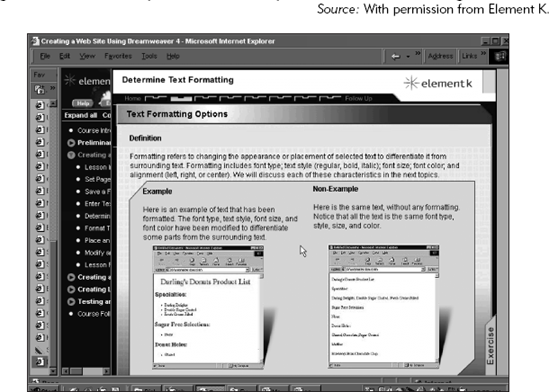

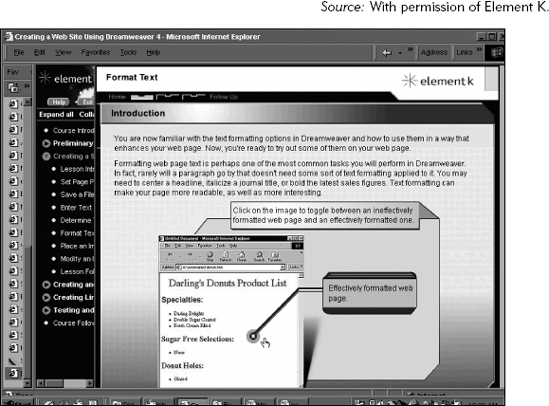

In a lesson on chairs, good nonexamples are stools and love seats. Figure 12.5 is a concept topic teaching text formatting options and displays side by side an example of a Web page that has applied formatting options and the same Web page without those options. A less-effective display of counterexamples is shown in Figure 12.6 where the learner must toggle between the example and nonexample and thus does not see them together.

For maximum benefit the learner should view the example and counterexample together as in Figure 12.5. Throughout this book we have displayed examples and nonexamples together to illustrate the application and violation of visual guidelines.

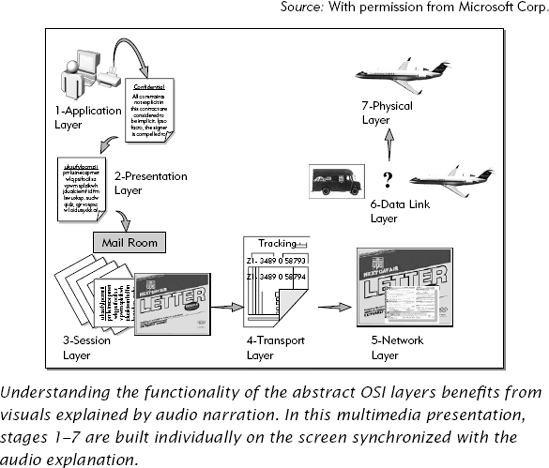

Abstract concepts such as integrity or value are difficult to visualize using representational graphics. Instead you might create a visual analogy. Newby, Ertmer, and Stepich (1995) found that analogies helped learners acquire new biology concepts such as peristalsis and pinocytosis. A more elaborate visual analogy involving creation, packaging, and distribution of mail is shown in Figure 12.7 to teach the seven OSI layers of the Internet. This analogy used audio explanation to relate each OSI layer to each phase in the mail creation, packaging, and delivery process.

Research suggests that you design analogies that (1) are familiar to the target audience, (2) are drawn from a different content area than the target concept itself, and (3) clearly indicate how the analogy is related to specific features or functions of the target concept (Newby, Ertmer, and Stepich, 1995). You will generally need to use words to explain your visual analogy. For the OSI analogy words were presented in audio narration during the animation.

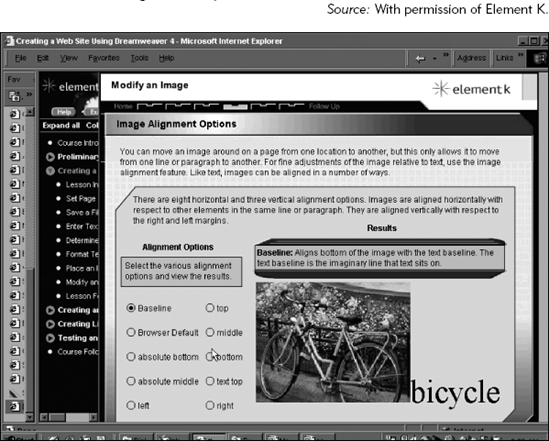

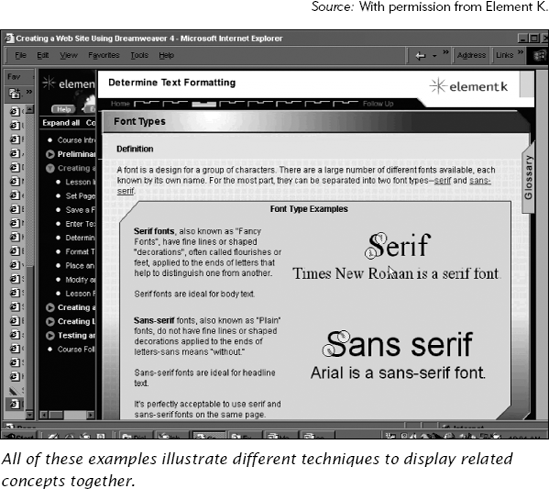

Figure 12.8 shows a short concept topic from a quality control course teaching the difference between defect and defective. The visuals placed close to the definitions and to each other make these related concepts immediately clear. Multimedia allows you a number of creative ways to illustrate coordinated concepts. For example the screen in Figure 12.9 illustrates different alignment options for text by simulating the effect of each option as the learner selects it from the left-hand list. Figure 12.3 shows several examples of a URL and at the same time illustrates the subordinate concepts of prototcol, domain, and path. When the learner clicks on any of the subordinate concepts such as path for example, all of the path elements in the URL examples turn a different color. Figure 12.10 illustrates two related concepts of serif and san serif font types. Each example is placed next to the textual description and uses a circle to draw attention to the relevant discriminators at the edges of the letters.

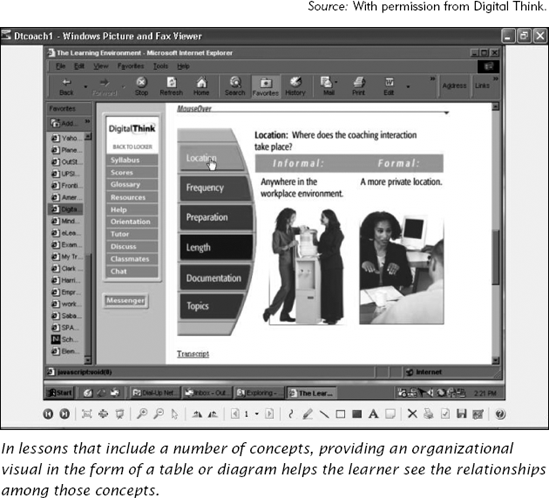

Robinson and Molina (2002) found that text placed in a tabular or matrix format is processed psychologically in the visual processing center and thus is a more effective way to display words about related concepts than sentences or outlines. For example, in Table 1.3 in Chapter One we listed the seven communication categories of visuals as a series of coordinate concepts. Tables are more effective because they use fewer words and physically organize ideas by topics and categories. Figure 12.11 uses an organizational visual to display a series of concepts related to coaching. When each level of the left organizing visual is clicked, the graphic and text on the right-hand side of the screen change to describe the topic selected.

Research has shown that learners who take time to study visuals learn more from them than learners who skip or skim them. (Gyselinck and Tardieu, 1999; Schnotz, Picard, and Hron, 1993). When you include some of the types of visuals described in this chapter to teach concepts, consider adding questions that will encourage learners to process them. For example, the interactive examples in Figures 12.3 and 12.9 engage the learner by directing her to take action on the screen in ways that promote processing of the visuals. A meaningful question about the visual is another way to promote deeper processing.

Secondly, you can engage learners with visuals of concepts by using visuals in practice exercises. As mentioned previously, to reinforce learning, concept practice should require learners to apply their new mental models to examples not seen during the lesson. For example, a course on Internet concepts could ask learners to select examples of valid URLs from a list. Or an online course on quality could ask learners to drag defective products to a "reject" area of the screen and type in the total number of defects and defectives identified. Whether the exercise is a multiple choice or a drag-and-drop is not as important as a question that requires learners to discriminate between valid and invalid instances of the new concept or coordinate concepts.

For concrete concepts, place two or more visual examples on the screen or page so they are contiguous to each other and to a text definition

Use representational graphics when the concept is concrete

Use cuing techniques and callouts to identify the discriminating features

For concrete concepts, place one or more visual counterexample(s) on the screen or page contiguous with examples

For abstract concepts, use visual analogies to make the ideas more concrete

For multiple concepts use organizational visuals to illustrate coordinate and subordinate relationships

Sequence important lesson concepts prior to the main lesson content such as task or process

Engage learners in concept visuals by making them interactive on the computer or by asking related questions about them

Use mouse rollovers for definitions where it is not important to compare; where it is important to simultaneously view two or more definitions or examples, display pop-ups that can remain in view until closed

Use visuals for practice of concepts that require learners to discriminate between valid and invalid instances of the concept

Omitting important concepts or providing only a brief definition without supporting examples

Using only one example to illustrate a complex and new concept

Failing to show examples contiguous with each other, with definitions, and with counterexamples

Embedding concepts in main lesson sections and thus overloading the learner

Including practice that asks learners to define concepts rather than to discriminate them

Locking learners into a sequential sequence for displaying examples and nonexamples. Concepts are ideal for engaging interactions where the learner has control of investigating samples and comparing them to nonexamples

Clark, R.C. (2000). Developing Technical Training. Silver Spring, MD: International Society for Performance Improvement.

Foshay, W.R. and others (2003). Writing Training Materials That Work. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Pfeiffer.

CHAPTER OUTLINE

What Are Facts?

Concrete versus Discrete Facts

Teaching Facts

Teach in Context

Provide Memory Support

On Automatic

How to Visualize Facts

Guideline 1: Use Representational Visuals Placed in Job Context to Illustrate Concrete Facts

When the Main Lesson Content is Facts

Guideline 2: Display Discrete Factual Data Where It Can Easily Be Seen When Needed

Guideline 3: Use Organizational Visuals to Display Multiple Discrete Facts

Guideline 4: Use Mnemonic Visuals When Physical Memory Aids Are Not Available

Guideline 5: Use Relational Visuals to Illustrate or Support Discovery of Relationships or Trends in Numeric Data

Guideline 6: Promote Engagement with Important Factual Visuals

Tips for Visualizing Facts

Common Mistakes to Avoid When Visualizing Factual Information