CHAPTER OVERVIEW

Procedure content dominates training courses and job aids that help learners perform routine tasks. In this chapter we define procedures as routine tasks that are effectively trained with demonstrations and practice using equipment and interfaces similar to those used on the job. We present research, psychological rationale, and examples to support the following guidelines for visualizing procedures:

Promote learning through demonstrations that combine transformational and representational visuals

Design transformational graphics that show activity flow from the performer's perspective in the job environment

Manage cognitive load in visual presentations when procedures or visuals are complex, learners are novice, or the presentation is instructionally paced, such as when it uses audio or animation

Use visuals to draw attention to and illustrate warnings

For online practice of computer procedures, support transformational visuals with on-screen contiguous text to provide directions, feedback, and memory support

Procedures are routine job tasks in which workers follow step-by-step action sequences each time they perform the task. Common work procedures include activities such as accessing e-mail, completing a routine customer order, changing copymachine cartridges, and measuring the electrical resistance of equipment during troubleshooting. Some procedures can be quite complex and/or have safety consequences such as landing an aircraft or administering CPR.

Procedures may include decisions as well as actions. Decisions in procedural tasks are clear-cut regarding specific conditions that lead to actions. Often such decisions are phrased in an if... then format. For example, routine troubleshooting procedures interlace decisions with actions such as if the heat warning indicator flashes, check the water level in the radiator.

Procedures are also called near-transfer tasks. That is because the psychological distance between how the procedure is learned in the training setting, and how it is performed on the job is short.

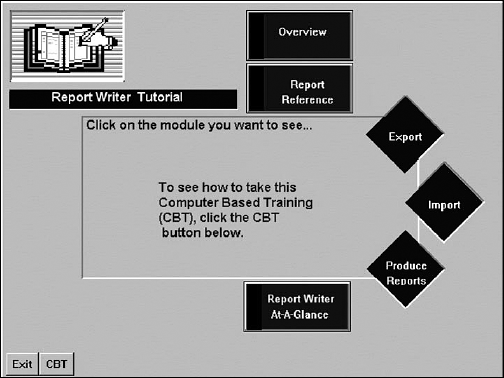

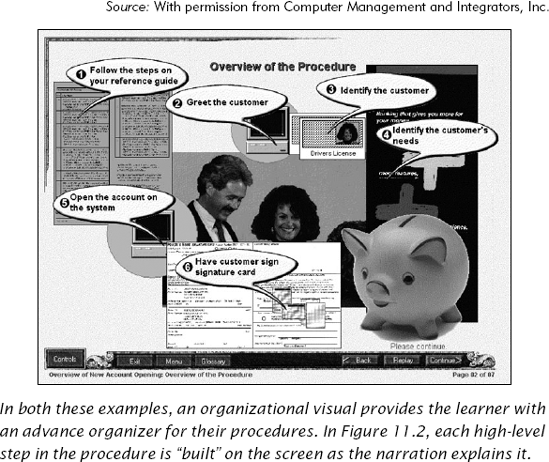

Introduce near-transfer tasks by orienting the learner to the job context in which the procedure is used as well as how the specific procedure might fit into other job tasks. An organizational visual is one good way to orient learners to the flow of procedures involved in a series of tasks. For example, Figure 11.1 shows an online course menu that summarizes the events in the entire procedure. Organizers such as the procedure overview shown in Figure 11.2 give thelearner a bird's eye view of how detailed procedures for setting up a savings account fit into an overall business flow.

Demonstrate the procedure's steps using the same tools or components as the ones used on the job. Following a demonstration, assign practice in which learners perform the procedure using the same or similar environment as will be used on the job. During practice sessions provide feedback that lets learners know how to correct errors or complete steps more effectively. Design job aids that summarize the procedural steps in order to provide memory support during and after training.

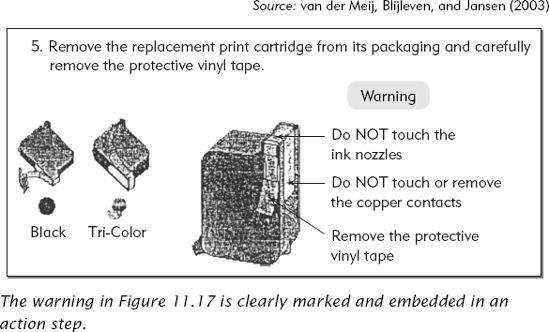

Finally, teach learners to avoid wrong turns by way of warnings. In some cases, a wrong turn can have serious consequences—some even safety related.

In other cases, a warning provided just at the moment a step is to be taken will prevent a wrong turn that could result in wasted time and frustrated users.

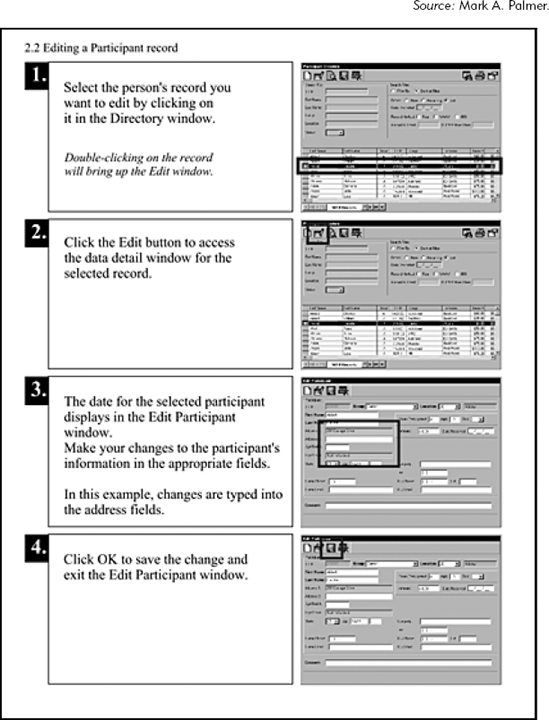

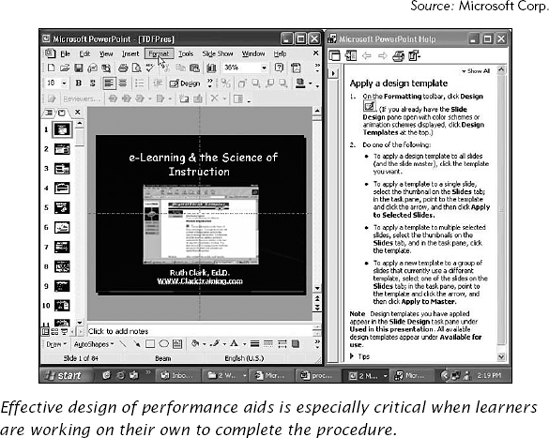

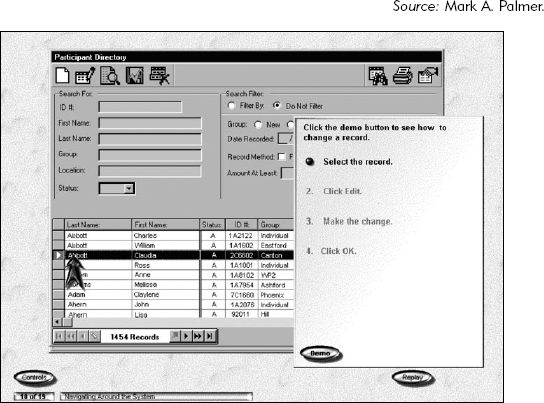

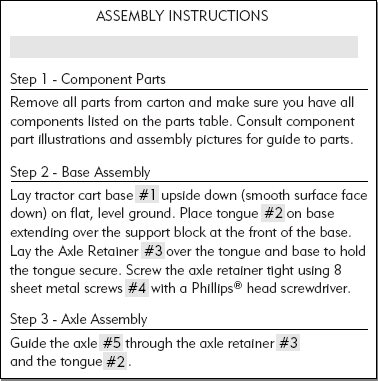

Sometimes training is not needed or feasible and the worker must perform the procedure by following directions on a performance aid. A common example is the gas pumping instructions found at self-service stations or the installation directions on the copy machine toner cartridge. Performance aids can be displayed on computer screens, cards, or in manuals. A common example is step-by-step directions for either equipment assembly or computer tasks. For example Figure 11.3 shows a job aid for a computer procedure, and Figure 11.4 shows a step-by-step guide as part of a computer help system. Since performance aids must stand on their own, the clarity of the instructions is critical. Likewise, inserting appropriate warnings into performance aids is also important since the workers are usually on their own to resolve any glitches they encounter along the way.

When training is necessary, work aids such as the one shown in Figure 11.3 can be used as memory support for performance back on the job. These aids are especially important for procedures that are performed relatively infrequently. Since training programs cannot usually afford to provide explicit demonstrations and practice on every possible procedure that might be needed, effective design and display of performance aids is critical to effective work outcomes.

In this section we review several guidelines for designing visuals that will help learners build near-transfer skills.

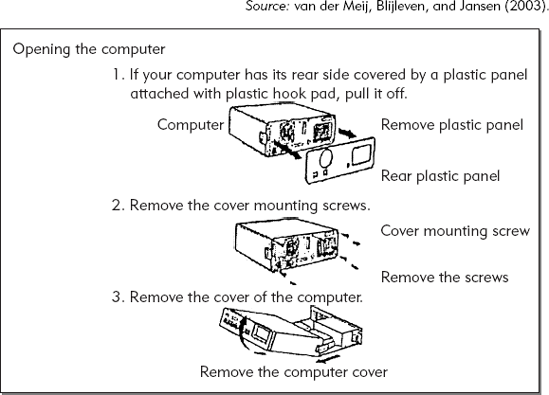

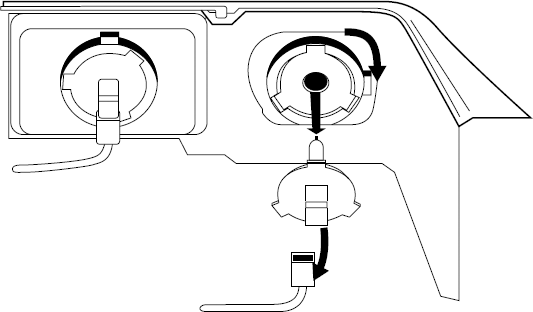

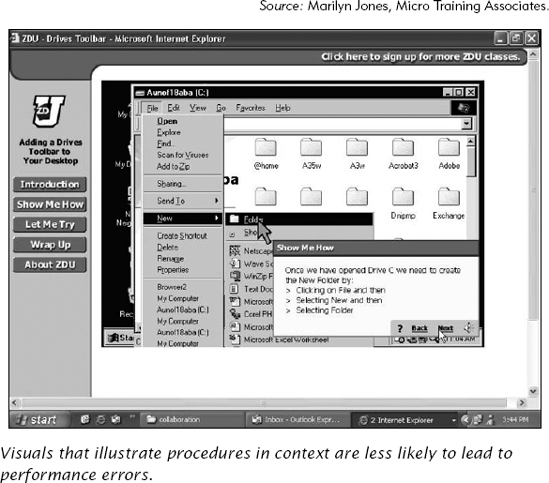

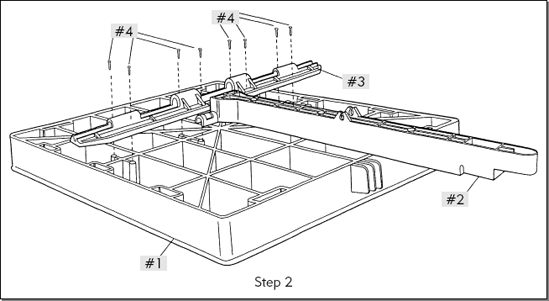

Help your learners acquire new procedural skills by demonstrating them in the same context as they will be performedin the work setting. Visuals that depict the equipment, screens, or relevant physical components used on the job promote transfer of learning. Thus, a transformational visual that incorporates representational visuals of the actualequipment or computer interface should serve as the main graphic element of any demonstration or performance guide. For example, in demonstrations of computer procedures, use graphics of the screens involved in the procedure as in Figure 11.5. In directions for equipment assembly or use, use visuals of the equipment as shown in Figure 11.6.

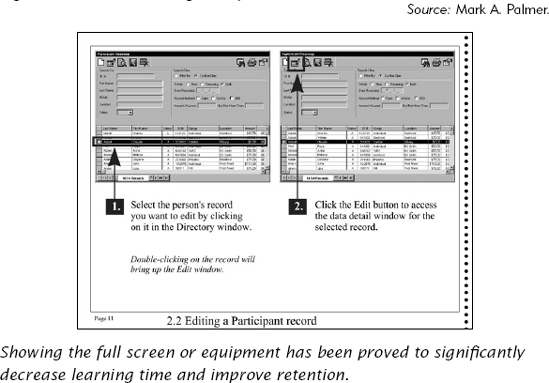

Van der Meij, Blijleven, and Jansen (2003) report significant learning benefits from including full screen captures in software manuals rather than relying on text alone or parts of screens. The use of full screen shots sequenced in a left-to-right layout such as shown in Figure 11.7 resulted in learning completion times that were 25 percent faster with 60 percent better retention of skills.

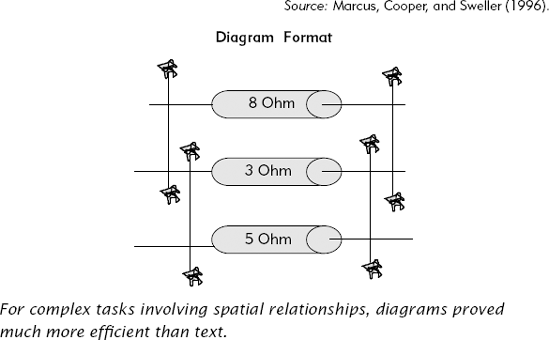

Marcus, Cooper, and Sweller (1996) report increased efficiency when they used diagrams only compared to text only topresent directions for connecting resistors in moderate to complex configurations. In some experiments, those using diagrams completed the task five times faster. The degree of learning or performance efficiency improvement seen in both these studies suggests that including effective visuals for procedures will generate a return on investment in the production costs of the visuals and the use of display real estate to show them.

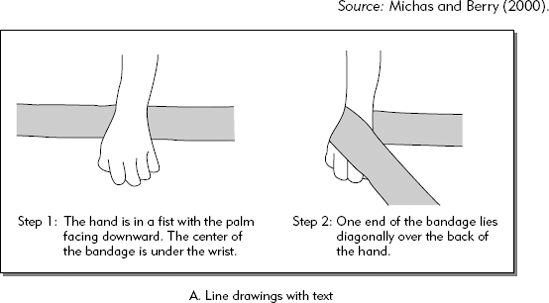

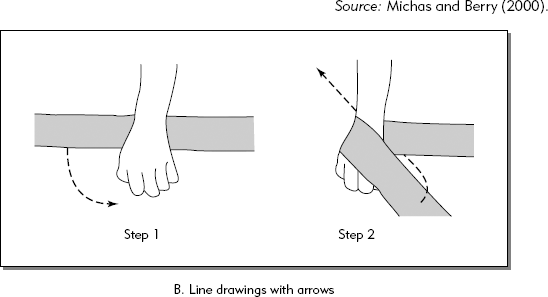

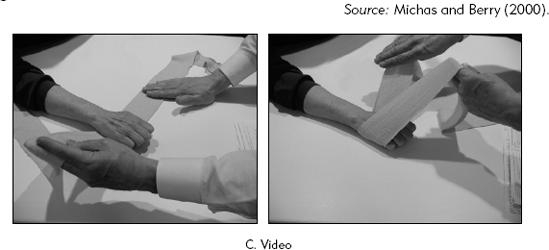

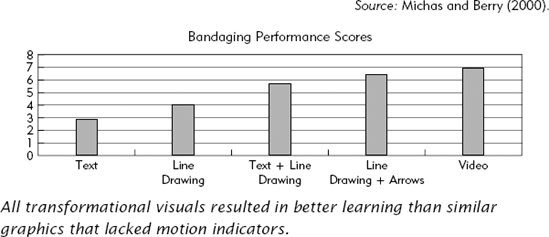

Transformational visuals show movement and recent research shows us that, at least for simple procedures, transformational graphics with different surface features can be effective. As long as the graphic communicates action, it works! Michas and Berry (2000) compared several different transformational visuals used to teach a bandaging task. The graphics included line drawings with arrows, line drawings with actions described by words, and video showing the actions as illustrated in Figure 11.8A,11.8B, and 11.8C. Learners could study the demonstrations for as long as they wished before they were asked to perform the procedure. As shown in Figure 11.9, all of the graphics that communicated action were effective. The transformational visuals were more effective than text alone or line drawings that lacked action indicators.

Michas and Berry (2000) conclude that "technically simple methods can be very effective when training people to perform simple procedural tasks, and that it is not always necessary to use advanced technology for such purposes" (p. 571).

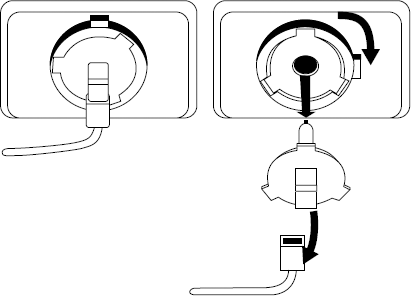

Whether displaying procedures with animated or still visuals, show the steps in job context from the performer's perspective. Using an over-the-shoulder video shot or three-dimensional perspective in a drawing gives the learner an accurate frame of reference.

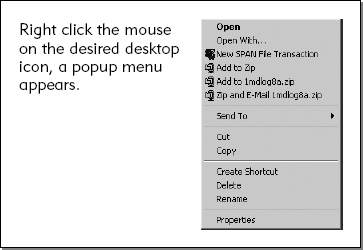

For example, Figure 11.10 shows a graphic designed to show novices how to replace the car headlight light bulb. Note, in this draft, there is no indication whether you are viewing the left or right headlight assembly—so a novice could easily get confused and replace the high beam bulb instead. Note that the corrected drawing, Figure 11.11, includes the side of the car, so that the novice user can identify which bulb is being replaced. In Figure 11.12, the designer felt that only the drop-down menu needed to be shown to illustrate the next step in a procedure. However, showing only the drop-down menu can be disorienting since different drop-downs can appear depending on the object the cursor is on when the right mouse button is clicked. In Figure 11.13, the designer includes more context, with the clicked-on object shown as well as the drop-down menu. Research summarized by Van der Meij, Blijleven, and Jansen (2003) shows that full screen captures increase learning time and retention compared to screen components shownout of context.

Van der Meij, Blijleven, and Jansen (2003) reviewed the visuals in a number of computer software and hardware manuals. They found that a large number of visuals (80 percent in software manuals and 48 percent in hardware manuals) used onlyflat pictures. Flat pictures are representational rather than transformational. The authors note that "In software manualsthe most striking finding for picture type used is the overwhelming presence of flat pictures. These picturesare all screen captures of which the majority are positioned within the action steps. The absence of any labeling or flow probably means a missed opportunity" (p. 171).

Instead of isolated flat pictures, visuals should be labeled and show flow such as in Figures 11.6 and 11.7. For equipment procedures, flows can be shown with three-dimensional line drawings supported by arrows as shown in Figure 11.6. For the computer procedure in Figure 11.7 the visual uses a horizontal left-to right alignment, visiblenumbers, and integrated action steps to show the sequence of actions and outcomes.

Cognitive overload can readily occur when a novice learner is first faced with a complex physical interface or a procedure with many detailed steps. Recent research points to a number of techniques you can use to manage load in the presentation of demonstrations or design of performance aids. We summarize these in the following paragraphs.

For a representational visual that is complex or a transformational visual that is an animation (with or without audio narration), use visual cues to direct attention. Jeung, Chandler, and Sweller (1997) report that narrating a demonstration is only helpful when a visual cue draws the eye to the visual elements being described. Visual search requirements aremuch higher when explanations are externally paced, such as a narration of a complex visual or animation. Note, for example, that the demonstration included in the CD and represented by a screen capture in Figure 11.5 uses a combination of animation and narration to demonstrate a procedure. Visual cuing (arrows and text bolding) draws the eye to the relevant part of the screen. Alternatively, in multimedia you can use a build technique to add text or visuals individually to a screen as they are described in the audio. Figure 11.7 is a paper version of the procedure shown in Figure 11.5. The lines and circles connect the text steps to the relevant portion of the screen and are colored in red to further direct attention.

As mentioned above, training often does not provide sufficient practice opportunities to build automatic performance. Therefore, learners need some form of memory support during practice exercises and when they return to the job. Memory support can take the form of brief text that summarizes the steps illustrated in a transformational visual or short text bullets that remain on the screen during a narrated sequence as shown in Figure 11.5. The bullets summarize the main action steps and can even be printed as a job aid. Reference aids can include both diagrams and text as reminders as shownin Figure 11.3.

When you explain a demonstration with audio, you effectively use the visual and auditory centers of working memory and thus maximize the limited capacity of working memory. As a result the learner can observe the actions and at the same time hear a coordinated description of the actions. As mentioned above, because narration typically runs at a pace outside the control of the learner, it's important to use visual cues to help focus attention quickly on the parts of the equipment or interface being described. Such animation sequences should be short and involve no more than four or five steps (7±2). One successful technique is to provide the major steps in text on the screen throughout the animation. As each one is explained, it is highlighted with bolding or a different color. This technique communicates the overall picture, highlights how the individual step fits into that picture, and elaborates on the specifics of each step. It's a good idea to include a replay button allowing the learner to review both the visuals and the words describing the visuals.

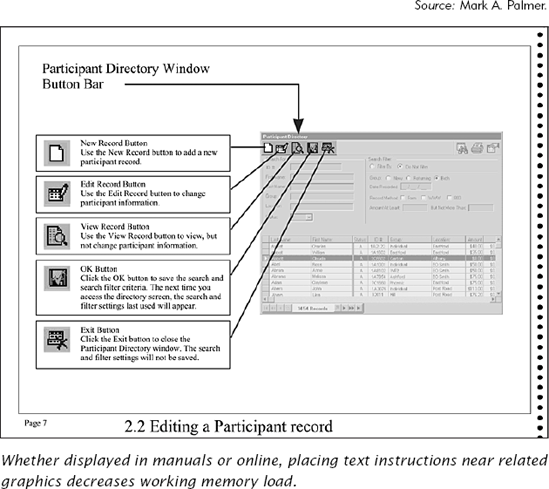

If a visual illustration is described by words presented in text, place each action phrase close to the relevant portion of the visual. This proximity allows learners to integrate the two sources of information more easily than if they have to read text in one location and then move their eyes to match it to the relevant part of the visual. Figures 11.14A and 11.14B show assembly instructions that are psychologically taxing because the graphic illustrations appear two pages away from the text directions. This separation requires one to flip back and forth in the manual and adds load to working memory. Contrast this with the layout of text and visual in the manual shown in Figure 11.15 in which the text and visuals are integrated.

Imagine connecting three resistors together by following these instructions:

Using the resistors supplied, make the following connections:

Connect one end of an 8-ohm resistor to one end of a 3-ohm resistor, and connect the other end of the 8-ohm resistor to the other end of the 3-ohm resistor;

Connect one end of the 3-ohm resistor to one end of a 5-ohm resistor, and connect the other end of the 3-ohm resistor to the other end of the 5-ohm resistor.

Now imagine performing the same task using the diagram shown in Figure 11.16. It won't come as any surprise that when the text and visual formats were compared in controlled research studies, the time to complete the task was significantly greater for those using the text formats. In four separate experiments, participants using the text version required from two to six times longer than those using the diagrams. The advantage of the diagram format, however, was most pronounced with relatively complex instructions like the ones shown above. When the task was simple such as connect one end of a 2-ohm resistor to one end of a 3-ohm resistor, there was minimal advantage to the diagrams. The level of difficulty of the task was rated by participants on a 1 (very easy) to 7 (very difficult) scale. On complex tasks, difficulty ratings were significantly higher for text directions than for diagram instructions. In contrast, for simple tasks, there was no difference in ratings between text and diagram instructions (Marcus, Cooper & Sweller, 1996). The authors conclude that "when cognitive load was low because element interactivity was low, the advantage of diagrams was lessened comparedto materials with a high cognitive load owing to high element interactivity" (p. 60). In other words, use diagrams to reduce cognitive load when the procedure involves complex spatial relationships.

If the equipment or interface used to perform the procedure is complex, eliminate extraneous visual detail by using line drawings or by graying out unneeded elements of the visual. Note, for example, that the representational visual shownin Figure 11.6 uses simple line drawings rather than photographs or shaded drawings. Be careful, however, not to eliminate any components involved in the procedure or to disorient the learner by showing portions of the interface out of job context as described under Guideline 2.

Avoiding unwanted states in procedures can sometimes be a matter of safety and other times a matter of annoyance andfrustration. Adapted from guidelines by van der Meij, Blijleven, and Jansen (2003), we recommend that effective warnings should 1) use a visual to draw the learner's attention 2) embed a consistent word such as "warning" or "caution" into the visual to help learners quickly identify the content 3) include a description about the risks and/or consequences of not complying with the warning 4) tell the user what to do or not to do and 5) include the warning either right before or inserted into the action step. Figure 11.17 shows one example of an effective warning from the van der Meij report. Note the use of a prominent graphic and text that dictates what not to do. In a survey of software and hardware manuals, van der Meij, Blijleven, and Jansen (2003) note that in only about two-thirds of the examples did the warning stand out on the page.

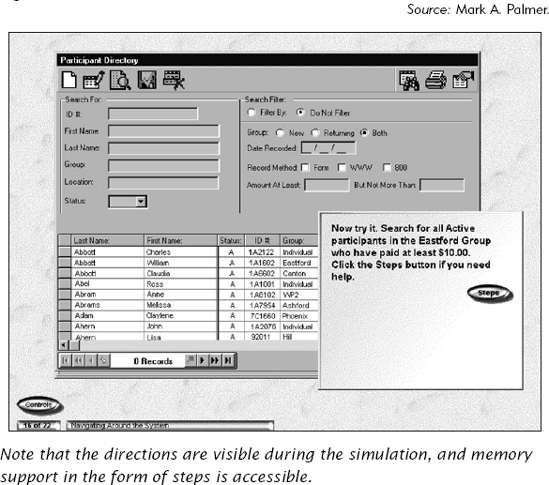

As mentioned previously, learners need hands-on practice performing the actual procedure. For procedures that involve computers, develop simulations that allow the learner to practice the steps. Typically, as part of the exercise directions, procedural simulations provide a scenario such as "complete an online order from Mary Smith who has ordered products X and Y delivered to her home address of such and such to arrive by May 30." The learner then accesses the simulated screens and fills in the fields to match the case data.

It is important to display the case data in text in a location readily available throughout the exercise, either directly on the screen as shown in Figure 11.18 or easily accessible on a pop-up or drop-down. An incorrect example would display the case data and directions on a screen separate from the simulation screen. This separation requires the learner to page back and forth and adds cognitive load to the exercise. At the very least, the information can be presented in a printable format and the learner instructed to print a copy to use during the exercise.

In addition to determining how to display the scenario detail, designers may have to determine how to display supporting performance aids such as step lists, cue cards, or even animated demos. For example, the lower right-hand button in the directions box in Figure 11.18 allows the learner to access the steps for help.

In general, feedback for computer simulations during initial practice is provided relatively frequently and in text placed close to where the learner has been asked to enter data. As the course progresses with additional practices, feedback may be diminished to include only normal error messages that the system would provide.

When first performing a procedure, learners should have access to the memory support they would have as on-the-job reference. If on-screen procedural support is available as part of the system as shown in Figure 11.4, access to this online help should be built into the simulation. Note that if you choose to re-create this online help, make sure to keep it updated to match the real application. If there is relatively little procedural help built into the software, then give learners access to a pop-up window that summarizes the steps in text as well as access to or replay of a demonstration of the steps. It is important that the learners have visual access to the memory support on the same screen where they are performing the actions as in Figure 11.4. Notice that the application is reduced and moved to the left to allow the learner to simultaneously see the application and the procedural directions.

Our discussion above pertains to learning computer procedures. However, during training of procedural skills that involve complex new motor skill learning, there is no substitute for actual hands-on practice in a laboratory situation and for memory support and job aids that meet the needs of the environment. As just one example, for busy technicians on the floor of an autoshop, laminated wall charts of key procedures posted next to the repair bay where those procedures are commonly done is a better solution than a paper manual kept on a shelf and easily disfigured by greasy hands.

In general, procedures often need several graphics in order to illustrate all the steps as unambiguously as possible. They typically require much more real estate and higher page counts than some other types of content. Keep the followingtips in mind as you plan visualizations for procedures:

On performance aids, use diagrams (with or without text) to illustrate procedural instructions that involve moderate to high spatial complexity

Design training and performance aids to effectively accommodate the representational and transformational visuals needed to illustrate the action steps

In manuals use left-to-right layout of full screens with numbered action steps that show action sequences

On computers, use animations of full screens accompanied by narration of action steps and text summaries of steps placed on the screen for memory support

On computers, keep number of steps demonstrated within the 7±2 guideline

On computers, introduce steps sequentially and prevent users from accessing them out of sequence

In manuals or computers integrate text labels or action steps into the illustration

In manuals or computers show the actions from the visual orientation of the performer

Use visuals to draw attention to warnings placed right before or within the action step

In training of computer procedures in e-learning, provide learners with opportunities to practice with simulations of the system that use representational visuals

Provide visual feedback by showing the actual system response to learner input (error message or next action)

Provide text feedback placed on the screen

Using visuals that do not accurately reflect the work environment

Using representative visuals that are not transformational, they do not show action flows

Showing the action area of the equipment or interface out of context of the whole equipment or screen

Failing to include or draw attention to warnings

Physically separating words from visuals

Failing to provide the learner with an orientation to where the procedure falls among a series of procedures or within the entire job task

Allowing learners to experience steps out of sequence

Procedures are one of the main types of content included in training courses designed to build task-specific skills. However, in order to perform many procedures learners will need supporting knowledge including related facts and concepts. In the next chapter we will summarize effective ways to visualize conceptual content followed by a chapter on the best ways to visualize facts.

Clark, R.C. (2000). Developing Technical Training. Silver Spring: MD: International Society of Performance Improvement.

Van der Meij, H., Blijleven, P., and Jansen, L. (2003). What makes up a procedure? In M. J. Albers and B. Mazur (Eds.), Content and complexity: Information Design in Technical Communication. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

CHAPTER OUTLINE

What Are Concepts?

Concrete versus Abstract Concepts

Teaching Concepts

How to Visualize Concepts

Guideline 1: Display Two or More Representational Graphic Examples Contiguous to Each Other and to Text Definitions

Guideline 2: Create a Visual Counterexample to Help the Learner Build Accurate Mental Models

Guideline 3: Use Visual Analogies Especially for More Abstract or Unfamiliar Concepts

Guideline 4: Display Related Concepts Together Applying the Contiguity Principle

Guideline 5: Use Organizational Visuals to Display Related Concepts and Their Features

Guideline 6: Promote Learner Engagement with Concept Visuals

Tips for Visualizing Concepts

Common Mistakes to Avoid when Visualizing Concepts