CHAPTER 4

Ham Radio Licenses and Frequencies

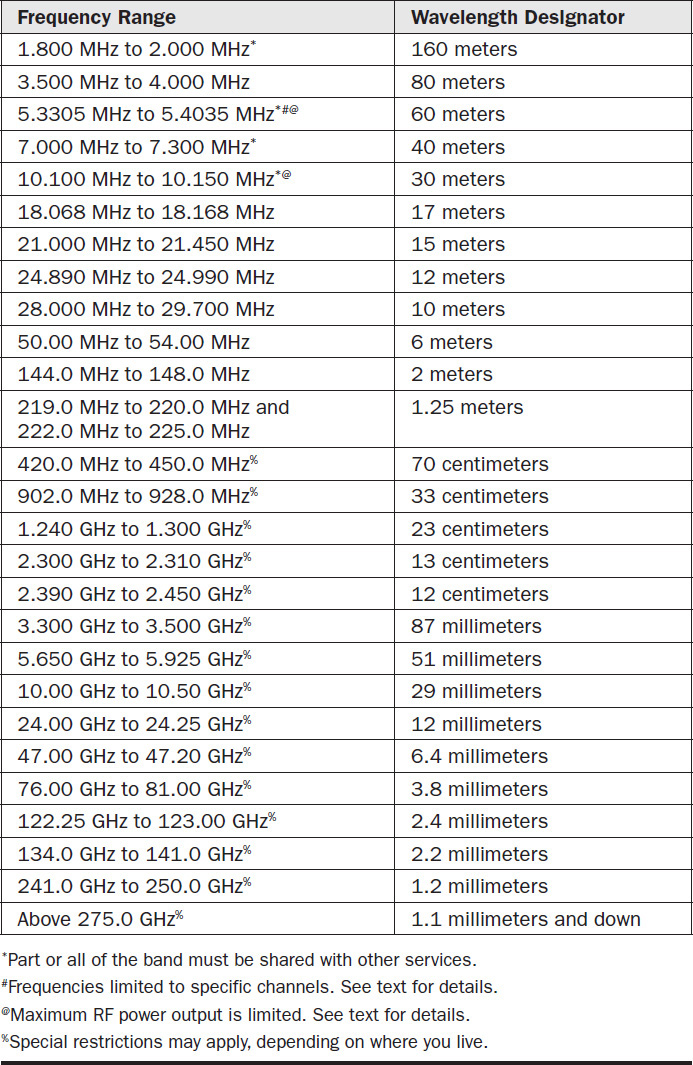

Amateur Radio operators enjoy operating privileges in numerous slices of the radio spectrum. Let’s take a look at the ham radio bands, learn how they work on the air, and outline the mode and power restrictions imposed by the FCC. The information given here is current as of February 2014 as I write this chapter. But things keep changing for radio hams! I recommend that you periodically visit the ARRL website for updates, including possible new bands or adjustments to existing bands.

TABLE 4-1 Amateur Radio bands in the United States. This data is effective as of 2014. For information about possible changes, visit www.arrl.org.

Today’s License Classes

If you don’t have a ham radio license but want to get into this hobby, you’ll have a choice of three license levels or “classes.” Most people start with a so-called Technician Class license, which conveys limited privileges, primarily using voice modes. More serious hams go for the General Class license or the Amateur Extra Class license. You must take written tests to get the licenses, but you don’t have to demonstrate any knowledge of, or proficiency in, the Morse code as you had to do in years gone by. The FCC eliminated that requirement after countries throughout the world agreed that “the code” no longer represented an essential communications skill.

Technician

Most new hams hold Technician level licenses. In order to get one, you must take a 35-question test and get at least 74 percent of the answers correct, or 26 “hits.” Volunteer hams administer the exams. Most local ham radio clubs hold regular examination sessions; if they don’t, one of their members will arrange to have a volunteer administer your test by appointment.

The test, as you can guess, deals with some fundamental technical stuff as well as important regulations imposed by the FCC. The Technician Class license test is fairly easy. If you’ve studied a basic electronics text or two, and if you’ve carefully gone over the FCC regulations as published in ARRL study guides, you should pass on your first try! Then you can legally transmit with RTTY, data, and voice modes on many, but not all, of the Amateur Radio frequency bands.

General

After you’ve held a Tech license for a while, you’ll probably want to upgrade to the General Class license. Then you’ll get nearly all of the frequency privileges that ham radio has to offer, from 160 meters (1.8 MHz) through the highest allocations in the super-high frequency (SHF) and microwave parts of the radio spectrum.

In order to upgrade your license class, you’ll have to take another test. The General Class exam goes into more depth than the Tech exam, particularly when it comes to electronics theory and communications practice. But once you have that piece of paper, you can get involved with all the known (and as yet unknown) communications modes.

Extra

The Amateur Extra Class license, often called simply the Extra, gives you full ham radio operating privileges on all bands to the extent allowed by the law, which, as I have already warned you, changes fairly often. In order to get this license, you’ll need to pass a rather difficult technical exam that has 50 questions, 37 of which you must answer correctly.

If you’re serious about ham radio and you really like to tinker with radios and their associated devices, or if you want access to the “prime space” in the HF bands where the best DX (foreign stations in exotic places) activity takes place, or if you simply want to hang out with the “cream of the crop,” you should consider getting the Amateur Extra Class license.

To “bone up” for the test, I recommend that you obtain and study the technical guides for the Extra Class license published by the ARRL, as well as my books Teach Yourself Electricity and Electronics, Electricity Demystified, and Electronics Demystified published by McGraw-Hill. Make certain that you get the latest editions.

Discontinued License Classes

Once in a while you’ll encounter a ham who claims to hold a license of some class other than the three described above. What’s up with that? Well, the ham radio licensing levels used to be a lot more complicated than they are today. The old classes went by the monikers Novice, Technician Plus, and Advanced. Although the FCC no longer issues new licenses for these classes, original ones remain valid.

The Novice Class license conveys restricted CW privileges on a few of the HF bands, along with some RTTY, data, and SSB privileges on 10 meters. In addition, voice and image mode privileges are available on 1.25 meters at 222 to 225 MHz, and also on 23 centimeters at 1.270 to 1.295 GHz.

The Technician Plus Class license “morphed” into today’s Technician Class license. In days gone by, Techs couldn’t operate on any of the HF bands; they were confined to 50 MHz and above. Today Techs can use the same CW band segments as Novices can, in addition to RTTY, data, imaging, message forwarding, and other more exotic modes on the VHF, UHF, SHF, and microwave bands.

The Advanced Class license originated many years ago, and then the FCC phased it out for a couple of decades. Later still, around 1970, the FCC brought it back when they implemented a stratified scheme known as incentive licensing. Presumably the FCC wanted to motivate as many hams as possible to gain technical knowledge and operating proficiency.

The Advanced Class license has vanished once more. New Advanced licenses are no longer issued. Some of the privileges taken away during the incentive licensing days have been restored. Advanced Class hams get to operate on a few more frequencies than Generals do, but Advanced operators don’t get everything.

160 Meters

The ham 160-meter band extends from 1.800 MHz to 2.000 MHz. That frequency range lies just above the upper limit of the standard AM broadcast band. Actually, it’s part of the MF spectrum, not the HF spectrum, which technically starts at 3 MHz and goes up to 30 MHz. Nevertheless, most hams think of 160 meters as an HF band.

Sharing with Other Services

Ham radio operators share the upper half of this band (1.900 MHz to 2.000 MHz) with radiolocation services. Old timers will remember these services as LORAN, an acronym that stands for LOng RAnge Navigation. By law, ham radio operators must avoid interfering with these services.

Characteristics

Experienced 160-meter operators know it as a winter nighttime band. Long-distance ionospheric propagation occurs only over paths that lie entirely or mostly on the dark side of the planet. During the daytime, the D layer ionizes to the extent that it prevents 1.8-MHz radio waves from getting to the higher layers where they could otherwise bend back to the surface. When the sun goes down, the D layer vanishes and 160 meters “opens up.”

Because waves at 1.8 MHz are so long, a good antenna must be long and high. A full-size dipole on this band measures 79 meters from end to end, and for optimum performance, it must dangle at least 40 meters above the ground. Not many hams have the real estate for anything like that. But smaller antennas can get you contacts; an inductively loaded vertical, mounted on the ground with a good radial system, will provide hours of fun.

Atmospheric noise in the form of sferics (“static”) presents a problem on 160 meters during the months when thundershowers commonly occur. For that reason, and also because the hours of darkness don’t last as long during those seasons (spring and summer) as they do in the fall and winter, you’ll find 160 meters most usable on cold, dark nights in November through February, when, along with a wood fire and a cup of coffee or hot chocolate, ham radio operation completes a great trio!

Allocations by Mode

The 160-meter band isn’t broken down into segments by mode. Hams can use CW, SSB, image, RTTY, and data modes on any frequency in the band.

Allocations by License Class

No class-specific subbands exist within the 160-meter band. Hams who hold General, Advanced, or Extra class licenses may use any frequency between 1.800 MHz and 2.000 MHz. The whole band is off-limits to Novice, Technician, and Technician Plus license holders. Some Novices, Techs, and Tech Plus hams find the desire to get 160-meter privileges sufficient motivation to upgrade!

80 Meters

The 80-meter band extends from 3.500 MHz to 4.000 MHz. Sometimes the upper half of this band is called 75 meters. But overall it averages 80 meters: In free space, an 80-meter wave has a frequency of 3.7500 MHz, precisely in the middle of the band. It’s a large band, considering its place in the spectrum, occupying fully 12.5 percent of the frequency space between DC (0 Hz) and 4.000 MHz. Hams are lucky indeed to have this band. Moreover, no sharing provisions impede hams’ full enjoyment of it. If you’re a ham, it’s all yours!

Characteristics

Like 160 meters, the 80-and-75-meter band works best at night, and better in the fall and winter than in the spring and summer. It’s that way for the same reasons: 80- to-75-meter waves propagate better when the D layer lacks ionization, and that’s during the hours of darkness. Also, sferics can present a problem in regions of the world where thunderstorms occur, and in most cases, that’s springtime and summertime.

While a full-size 80-and-75-meter antenna isn’t as imposing as its 160-meter counterpart, a good dipole at a reasonable height still takes up a lot of space. If you have the land and the clearance for it, a 40-meter-long wire, center fed and elevated 20 meters or more above the ground, will serve you well on all the frequencies from 3.500 MHz to 4.000 MHz if you cut it for the center of the band at 3.750 MHz.

With a good receiver, a low-noise QTH (location), and a high-power transmitter, a full-size dipole antenna up 30 meters or more in length will allow you to “work the world” over any propagation path that lies on the dark side of the globe. During the daytime, however, no antenna will likely get you contacts over distances greater than 800 kilometers or so.

Allocations by Mode

Most of the HF ham bands have segments designated for use with specific modes. Perhaps better stated, the suballocations restrict usage to certain modes. On this particular band, you may use only digital modes on the lowermost 100 kHz (3.500 MHz to 3.600 MHz). Those modes include CW, RTTY, PSK, MFSK, and data transmission. Other, more exotic digital modes are also allowed.

On the “lion’s share” of the 80-and-75-meter band, going from 3.600 MHz to 4.000 MHz, voice (also called phone) and image emissions are allowed. So-called “75-meter sideband” or “75-meter phone” enjoys huge popularity in the United States, especially on winter nights when you can hear signals from all over the continent with ease. Often the band gets downright crowded! Always remember to stay within the subbands allowed for your license level.

Allocations by License Class

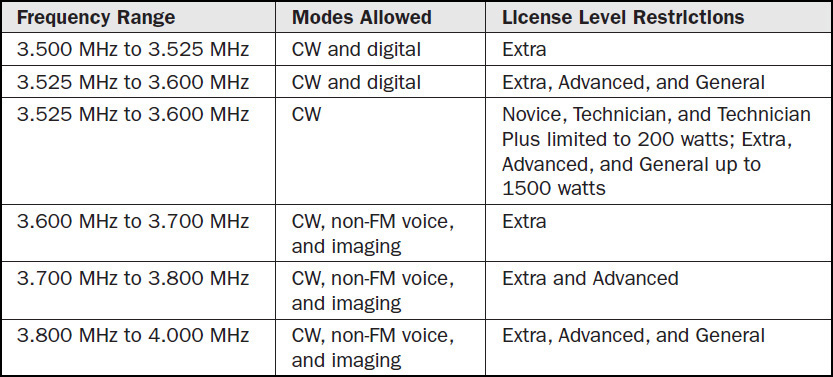

The 80-and-75-meter band contains various segments allocated according to license class. Extra Class operators can use all the bands from top to bottom, including this one. Other license classes have privileges as follows:

• Advanced Class hams can use the ranges from 3.525 MHz to 3.600 MHz for digital operation, and 3.700 MHz to 4.000 MHz for phone and imaging communications.

• General Class hams can use the ranges from 3.525 MHz to 3.600 MHz for digital operation, and 3.800 MHz to 4.000 MHz for phone and imaging.

• Novices, Technicians, and Tech Plus operators can use the frequencies from 3.525 MHz to 3.600 MHz for CW operation only, with a maximum of 200 watts peak envelope power (PEP) output.

The ratio of PEP to the average power depends on the emission mode. If you send out a constant, unmodulated, pure carrier, the PEP equals the average power. The same holds true for FSK and PSK modes. For CW, it varies a little bit, depending on your sending quirks, but usually the average power is about 40 to 50 percent of the PEP. For SSB voice without compression or clipping or other processing, the ratio hovers around 25 to 33 percent. For FM, as with FSK and PSK, it’s 100 percent (1 to 1).

Table 4-2 breaks down the 80-and-75-meter band according to license class suballocations and mode usage restrictions.

TABLE 4-2 Suballocations in the United States for the 80-and-75-meter band (3.500 MHz to 4.000 MHz) as of March 2012. Please note that this information will likely change in the coming years, so you might want to double-check this table against the ARRL website or the latest edition of The ARRL Handbook.

60 Meters

The band known as 60 meters does not comprise a continuous span of frequencies as the other ham bands do; instead, it has well-defined channels, each one 3.000 kHz wide and centered at the following frequencies as of this writing:

• 5.3320 MHz

• 5.3480 MHz

• 5.3585 MHz

• 5.3730 MHz

• 5.4050 MHz

Your signal can’t legally exceed 2.800 kHz in bandwidth, and you must center your signal to coincide precisely with the channel center. This notion is simple for digital modes but a little more complicated for USB. You don’t want to set your transmitter’s suppressed carrier frequency to coincide with a channel center. If you do that, part of your emitted energy will stray outside the channel on the high end. Ideally, you should “tweak” your suppressed carrier frequency so that it lies 1.500 kHz below the channel center. Then, if your radio is typical and has an audio passband of 300 Hz to 3000 Hz and an RF filter that trims your signal to 2.700 kHz of bandwidth, your energy will lie entirely within the channel; in fact, you’ll have a little bit of room to spare on the low end.

Sharing with Other Services

Hams must share the 60-meter band with other services, taking pains to avoid interfering with those services. Only one signal may exist at a given time, audible from a given location, on a given channel. So if you hear someone having a contact on a particular channel, don’t transmit there.

Characteristics

Like 80 meters and 160 meters, the 60-meter band works better for long-haul contacts when most, or all, of the signal travels over the dark side of the earth. However, the effect is not quite as pronounced. Once in a while, you’ll hear stations from 1600 kilometers to 3200 kilometers away during the daytime, especially if the sun rests low in the sky.

Also like 80 meters and 160 meters, the part of the spectrum around 5 MHz suffers adverse effects on account of sferics during the thunderstorm season. However, the problem is not quite so severe or extensive here as it is on those lower bands. In general, as the frequency goes up, sferics propagate for shorter and shorter distances before they fade down enough to give you a break! So don’t let the fact that it’s a summer day in the American Midwest deter you from listening on this band.

You can get an idea of the propagation conditions between Colorado, USA and your QTH on 60 meters at any time by tuning your radio to 5.000 MHz and listening for the time broadcast station WWV, operated by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). You can also find out about propagation conditions between Hawaii and your location by looking out for WWVH on the same frequency. Once in a while, you’ll hear both stations at the same time, competing with each other!

Allocations by Mode

You may use USB mode for voice (not LSB), as well as the common digital modes, such as CW, RTTY, PSK, on 60 meters. Old-fashioned AM voice and FM voice are forbidden. Your transmitter must not put out more than 100 watts PEP.

Allocations by License Class

Anyone who holds an Extra, Advanced, or General class license may use any channel in the 60-meter band, keeping in mind the restrictions outlined above.

40 Meters

The 40-meter band spans 7.000 MHz to 7.300 MHz. In free space, a 40-meter-long wave has a frequency of 7.500 MHz, slightly above the ham band, whose center frequency actually lies just under 42 meters.

Sharing with Other Services

Amateur Radio operators enjoy full privileges on this band, not legally having to yield to anybody else. But the theory of law and practical reality sometimes diverge, and this band offers a good example of that circumstance. The upper 1/3 of the band, at frequencies between 7.200 MHz and 7.300 MHz, harbors high-powered AM shortwave broadcast stations scattered around the globe. Hams using SSB in this part of the band will notice these signals as they pass through receiver product detectors; they’ll sound like heterodynes or “beat notes” with space-alien-like “monkey chatter” superimposed.

Characteristics

The 40-meter ham band treats signals just about the same way as the 41-meter shortwave broadcast band does. During the day, you can communicate reliably at distances of up to about 1600 kilometers. Conditions tend to be a little better in the fall and winter because sferics, and atmospheric noise in general, are less intense than they are in the spring and summer. The band “opens up” at night all year round, except when a solar disturbance disrupts shortwave propagation in general.

On a winter night when solar activity is high but not out of control, the 40-meter band can provide you with hours of fun, even if you can manage only a low dipole as an antenna. A half-wave dipole measures about 20 meters from end to end on this band. If you can get it up at least 10 meters, you’ll get fine results. Of course, as with most ham antennas, you should string your antenna up as high as you can.

Allocations by Mode

On 40 meters, you may use only digital modes on the lowermost 125 kHz (7.000 MHz to 7.125 MHz), including CW, RTTY, PSK, MFSK, data transmission, and other more exotic digital modes. Between 7.125 MHz and 7.300 MHz, phone and image emissions are allowed. Like its counterpart on 75 meters, “40-meter phone” gets a lot of use. Remember to stay within the subbands allowed for your license class.

Allocations by License Class

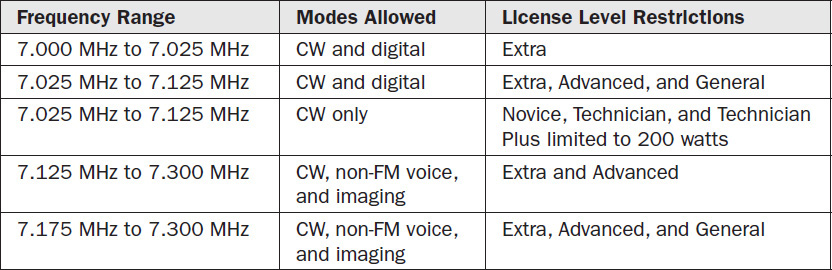

Extra Class operators can use the whole 40-meter band, subject to mode restrictions. Other license classes have privileges as follows:

• Advanced Class licensees can use the ranges from 7.025 MHz to 7.125 MHz for digital operation, and 7.125 MHz to 7.300 MHz for phone and imaging communications.

• General Class operators can use the ranges from 7.025 MHz to 7.125 MHz for digital operation, and 7.175 MHz to 7.300 MHz for phone and imaging.

• Novices, Technicians, and Tech Plus operators can use the frequencies from 7.025 MHz to 7.125 MHz for CW operation only, with a maximum of 200 watts output.

Table 4-3 breaks down the 40-meter band according to license class suballocations and mode usage restrictions.

TABLE 4-3 Suballocations in the United States for the 40-meter band (7.000 MHz to 7.300 MHz) as of March 2012. Please note that this information will likely change in the coming years, so you might want to double-check this table against the ARRL website or the latest edition of The ARRL Handbook.

30 Meters

The ham band at 30 meters extends from 10.100 MHz to 10.150 MHz, so it’s a relatively small band compared with most other HF bands. Nevertheless, you can have a lot of fun in this little span of frequencies. I remember the days when hams dreamed of having a band here; 40 meters and 20 meters seemed separated by a gigantic gulf. No longer!

Sharing with Other Services

Amateur Radio operators must share this band with fixed services outside the United States. When you operate on 30 meters, you must make sure that you don’t interfere with those services.

Characteristics

This band, like the 31-meter shortwave broadcast band, lies in a “transition zone” as you go up in frequency, where the propagation begins to get better in the daytime than at night. You can expect to make contacts all over the world when most, or all, of the path lies in darkness. When most, or all, of the path lies in daylight, you can hear, and be heard, over distances up to around 5000 kilometers on a regular basis. Sferics will bother you less on this band than they do on 80-and-75, 60, or 40 meters.

You can get away with a modest-size antenna on 30 meters. A half-wave dipole spans 14 meters from end to end; if you cut it for 10.125 MHz at the exact center of the band, you’ll get a good impedance match to 50-ohm or 75-ohm coaxial cable over the entire range. If you can get that dipole up at least 7 meters, you can expect decent results. A full-size quarter-wave vertical antenna measures about 7 meters tall.

You have an asset here similar to the one you can enjoy on 60 meters. To check the propagation conditions between Colorado, USA and your location on 30 meters, tune to 10.000 MHz and listen for WWV. You might also hear WWVH at the same time as, or instead of, WWV. Both stations identify themselves periodically, so if you have any doubt about which of them you’re hearing, listen for a while.

Allocations by Mode

No matter where you operate in the 30-meter band, you must restrict your work to digital modes only, including RTTY, PSK, MFSK, data, and of course, CW. Your transmitter cannot put out more than 200 watts PEP.

Allocations by License Class

If you have a General, Advanced, or Extra Class license, you can operate on any frequency in the band. If you’re a Novice, Tech, or Tech Plus operator, you’ll have to upgrade at least to General before you can transmit on 30 meters.

20 Meters

The 20-meter band goes from 14.000 MHz to 14.350 MHz. Hams don’t have to share this band with any other services. Only General, Advanced, and Extra Class operators have access to this choice span of frequencies, but they can use up to the full legal limit of transmitter output power (1500 watts PEP) throughout.

As one of the best all-around long-range communication bands, 20 meters probably constitutes the single most popular span of frequencies allocated to radio hams today. Because it can get crowded, this band occasionally harbors people who get impatient, and even rude, with their fellow operators.

Once in a while, you’ll hear a “lid” (poor operator) on this band who simply acts hostile or irrational. Never reciprocate in kind; maintain your courtesy no matter how rotten somebody else gets.

Characteristics

The 20-meter Amateur Radio band behaves rather like the shortwave broadcast 22-meter and 19-meter bands. During the day, you can communicate reliably all over the globe when conditions are decent. On this band and all the HF bands at higher frequencies (shorter wavelengths), the light/dark propagation dichotomy reverses from its lower-frequency state. In other words, “20 meters and down” do better, generally, over sunlit paths than they do over dark paths. However, at and near sunspot cycle peaks, the 20-meter band offers worldwide communications with low power and modest antennas 24 hours a day, especially in the summer at latitudes close to the geographic poles.

On a spring or summer afternoon when solar activity is high but not stormy, the 20-meter band can provide holders of General, Advanced, and Extra Class licenses a good deal of fun, including plenty of DX (long distance to foreign countries). A half-wave dipole measures about 10 meters from end to end on this band. If you can get it up at least 5 meters, it’ll work okay. Another alternative is the ground-plane antenna, essentially a quarter-wave vertical with three or four quarter-wave radials and with its base elevated at least a quarter wavelength above the earth’s surface. This type of antenna measures roughly 5 meters tall, and the radials measure the same length.

You can get a good clue as to the conditions between Colorado or Hawaii and your location on 20 meters by setting your radio to 15.000 MHz and listening for WWV and/or WWVH. If you hear only one of them, make sure that you know which one is coming in! You might get a surprise when you think you’re hearing WWV and, in fact, it’s WWVH (or vice-versa).

Allocations by Mode

You may use only digital modes on the lowermost 150 kHz (14.000 MHz to 14.150 MHz), including CW, RTTY, PSK, MFSK, data transmission, and their “cousins.” Between 14.150 MHz and 14.350 MHz, you may put out phone and image emissions. Of course, you must adhere to the license class restrictions when choosing a frequency.

Allocations by License Class

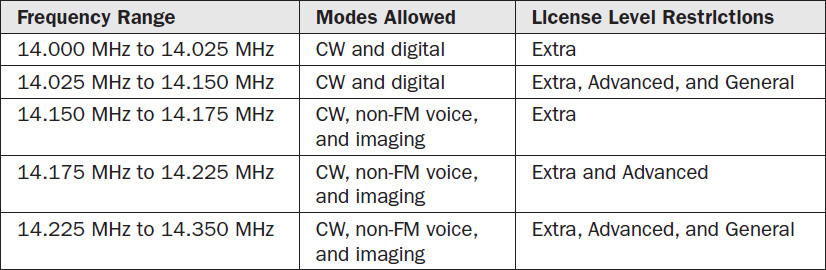

Extra Class operators can use the whole 20-meter band, subject to mode restrictions. Other license classes have privileges as follows:

• Advanced Class licensees can use the ranges from 14.025 MHz to 14.150 MHz for digital operation, and 14.175 MHz to 14.350 MHz for phone and imaging operation.

• General Class operators can use the spans from 14.025 MHz to 14.150 MHz for digital operation, and 14.225 MHz to 14.350 MHz for phone and imaging contacts.

• The 20-meter band is off-limits to Novices, Technicians, and Tech Plus operators. The prospect of getting on this band has motivated a lot of people to upgrade!

Table 4-4 breaks down the 20-meter band according to license class suballocations and mode usage restrictions.

TABLE 4-4 Suballocations in the United States for the 20-meter band (14.000 MHz to 14.350 MHz) as of March 2012. Please note that this information will likely change in the coming years, so you might want to double-check this table against the ARRL website or the latest edition of The ARRL Handbook.

17 Meters

Ham radio operators can use the frequency span from 18.068 to 18.168 MHz, commonly called 17 meters. For experimenters and technophiles, it’s a neat slot between the larger, more crowded, and frequently contest-cluttered 20-meter and 15-meter bands. It’s great for DX, too! Hams don’t have to share 17 meters as they do with 30 meters, and full legal power is allowed.

Characteristics

This band behaves like the 16-meter and 15-meter shortwave broadcast bands, which lie close to it in frequency. You can make contacts all over the world when most, or all, of the path lies on the daylight side of the planet and conditions are decent. Sferics will give you far less grief here than on lower bands. In fact, unless a thunderstorm looms on your doorstep, you won’t hear much, if any, atmospheric “static” on 17 meters. Humanmade noise presents a different conundrum. I, for one, have trouble with rogue neighborhood electrical appliances on this band.

You can get away with a rather small antenna on 17 meters. A half-wave dipole spans only about 8 meters from end to end; if you cut it for 18.118 MHz at the band center, you’ll get a good match to 50-ohm or 75-ohm coax over the whole band. If you can get that dipole up at least 4 meters, you can expect fair results, but if you want to work DX, you should elevate it at least 8 meters above the ground. A quarter-wave vertical measures only about 4 meters tall on this band.

A simple ground-plane antenna is an excellent option on 17 meters for those with a serious DX interest and a modest budget. The radiating element will be about 4 meters tall, and the radials, which can slope down at an angle and serve as guy wires, will also measure roughly 4 meters long, kept at the proper length with egg insulators. If you put the feed point above the ground at least 4 meters, the whole structure will measure only 8 meters from the mounting surface to the tip of the radiator!

Allocations by Mode

On the 17-meter band, you must restrict your work to digital modes only, including RTTY, PSK, MFSK, data, and CW, below 18.110 MHz. Above that frequency, you can use phone and imaging emissions.

Allocations by License Class

If you have a General, Advanced, or Extra Class license, you can operate on any frequency within the 17-meter band. If you’re a Novice, Tech, or Tech Plus operator, you’ll have to upgrade at least to General before you can transmit here.

15 Meters

The 15-meter Amateur Radio band occupies the spectrum span from 21.000 MHz to 21.450 MHz. It’s almost entirely a daylight-path band; at night the upper layers of the ionosphere rarely have enough density to return signals to the surface, although exceptions do occur, especially near sunspot cycle peaks. In terms of absolute spectrum space, 15 meters is almost as large as the 80-and-75-meter band. Hams have full privileges here, without any need to worry about interfering with other services.

Characteristics

The ham 15-meter band behaves like the shortwave broadcast 13-meter band. It’s a great place in the spectrum for working DX when conditions allow. You don’t need much transmitter output power to “work the world” even with a modest antenna, such as a dipole or ground plane, and those antennas have manageable dimensions. A half-wave dipole measures only about 7 meters from end to end, and a full-size, quarter-wave vertical rises only about 3.5 meters up from the feed point.

On 15 meters, complex directional antennas become mechanically manageable even for the ham without civil engineering experience, providing gain (extra transmitted power) in favored directions and attenuation (suppression) of received signals from unwanted directions. Lots of hams use Yagi antennas, also called beams, on this band. In addition to having reasonable size themselves, antennas on 15 meters don’t have to be mounted very far above the surface to provide excellent DX performance. If you can get your antenna 15 meters above the ground, it’ll sit a full wavelength up there, and you’ll get excellent low-angle radiation and reception.

Allocations by Mode

Amateur Radio operators may legally use only digital and data modes between 21.000 MHz and 21.200 MHz, including CW, RTTY, PSK, MFSK, data, and similar emissions. Between 21.200 MHz and 21.450 MHz, hams are allowed to transmit with phone and image emissions, subject to license class restrictions.

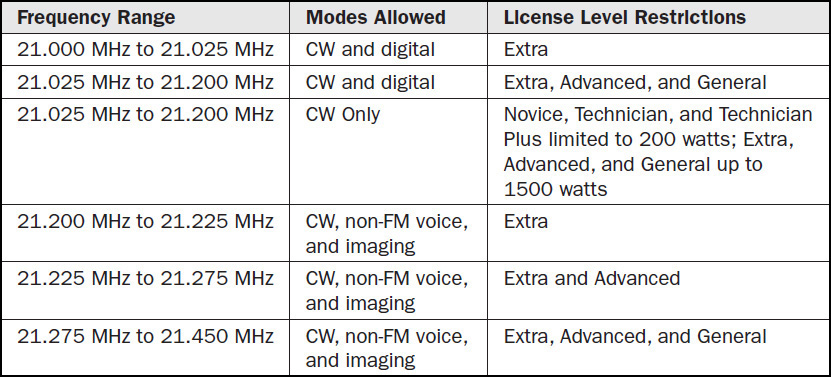

Allocations by License Class

Extra Class operators can use the whole 20-meter band, subject to mode constraints. Other license classes have privileges as follows:

• Advanced Class licensees can use the ranges from 21.025 MHz to 21.200 MHz for digital operation, and 21.225 MHz to 21.450 MHz for phone and imaging communications.

• General Class operators can use the spans from 21.025 MHz to 21.200 MHz for digital operation, and 21.275 MHz to 21.450 MHz for phone and imaging contacts.

• Novices, Technicians, and Tech Plus operators can use the frequencies from 21.025 MHz to 21.200 MHz for CW operation only, limited to 200 watts RF output power.

Table 4-5 breaks down the 15-meter band according to license class suballocations and mode usage restrictions.

TABLE 4-5 Suballocations in the United States for the 15-meter band (21.000 MHz to 21.450 MHz) as of March 2012. Please note that this information will likely change in the coming years, so you might want to double-check this table against the ARRL website or the latest edition of The ARRL Handbook.

12 Meters

The 12-meter Amateur Radio band covers 24.890 MHz to 24.990 MHz. This band is actually closer to 25 MHz than to 24 MHz, and lies about midway between 15 meters and 10 meters. It’s a good place for experimenters and serious DXers. The full legal limit is allowed, and there’s no sharing, either!

Characteristics

This band behaves like the 11-meter shortwave broadcast band. You can make contacts all over the world near the times of sunspot maxima when most, or all, of the path lies on the sunlit side of the earth. Sferics almost never pose a problem; if you hear “thunderstorm static” on 12 meters, you’d do well to go outside and see if a dark cloud is about to come over you.

A half-wave dipole for 12 meters spans roughly 5.7 meters from end to end; if you cut it for 24.940 MHz at the band center, you’ll get a good match to 50-ohm or 75-ohm cable over the whole band. You can make lots of contacts if you can get that dipole outdoors and high enough so that a tall person won’t run into it.

A ground-plane antenna can yield amazing DX results on 12 meters when propagation conditions are good, and you can build one with hardware-store parts! The radiating element measures about 2.9 meters tall. You can cut radials that double as guy wires to the same length as the radiating element. You’ll have to “tweak” the element lengths a little to get the lowest SWR possible at 24.940 MHz.

Allocations by Mode

On 12 meters, you must restrict your work to digital modes only, including RTTY, PSK, MFSK, data, and CW, between 24.890 MHz and 24.930 MHz. Above 24.930 MHz and all the way up to 24.990 MHz, you can use phone and imaging emissions.

Allocations by License Class

If you have a General, Advanced, or Extra Class license, you can operate over the whole 12-meter band. If you’re a Novice, Tech, or Tech Plus operator, you’ll have to upgrade at least to General before you can fire up your transmitter here, except into a dummy load.

10 Meters

If you’ve had experience with Citizens Band (CB) radios, you should have a good idea of how the 10-meter ham band treats signals. It’s a big band, extending from 28.000 MHz to 29.700 MHz. Amateur Radio operators enjoy unrestricted use of the band; it involves no sharing with other services. If you have a General, Advanced, or Extra Class license, you can use any frequency in the band and put out up to 1500 watts PEP.

Characteristics

Because of its ability to provide spectacular worldwide communications with low transmitter power output under ideal conditions, 10 meters has acquired the nickname “magic band.” Over daylight paths, especially in spring and summer and in years near the sunspot cycle maximum, you can work DX with less than a watt of RF at your antenna. And the antenna itself can be modest; a ground plane or dipole only a few meters above the ground will do the job! Of course, you can run higher power and use more sophisticated antennas if you want, but QRP (low power) operation with simple antennas has proven great fun for a lot of technically oriented hams, myself included.

On the downside, the 10-meter band spends a great deal of time in “hibernation,” when it behaves more like a VHF band than an HF band. In the wintertime, at night, or during sunspot minima, you will often find that contacts are possible only up to distances of 30 to 40 kilometers on this band. Ionospheric propagation goes away entirely. Nevertheless, you should never assume that 10 meters is dead just because you don’t hear any signals there. Sometimes people, hearing nothing on 10 meters, assume it’s dead when in fact it’s wide open! I call this psychological phenomenon the “Dead Band Delusion.” So why not send a CQ or two?

Allocations by Mode

Only the digital modes (RTTY, PSK, MFSK, data, and CW) are allowed between 28.000 MHz and 28.300 MHz. From 28.300 MHz to 29.700 MHz, you can use voice and imaging emissions.

Allocations by License Class

If you have a General, Advanced, or Extra Class license, you can operate over the whole 10-meter band using the emissions as described above. If you’re a Novice, Tech, or Tech Plus operator, you can use any of the digital modes between 28.000 and 28.300 MHz, and SSB phone between 28.300 MHz and 28.500 MHz, keeping your power output at or under 200 watts PEP.

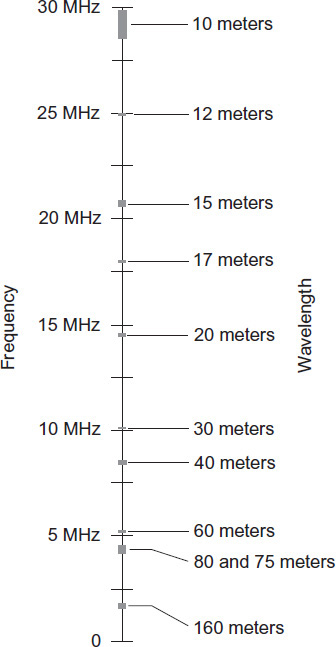

FIGURE 4-1 The ham radio bands below 30 MHz as of 2013, on a linear scale according to frequency.

6 Meters

Amateur Radio operators have 6-meter privileges between 50.000 MHz and 54.000 MHz. In terms of frequency, 6 meters constitutes the lowest of the three VHF ham bands, the others being 2 meters and 1.25 meters. Like 10 meters, this band can seem magical, opening up to the world with ionospheric propagation every once in a while. Such events are rare, but if you listen on this band long enough, you’ll see some cool things happen here. Radio hams have the whole band to themselves, and can use up to the legal power limit.

Characteristics

Most of the time, 6 meters offers line-of-sight communications up to 30 or 40 kilometers on a reliable basis. Tropospheric scattering and bending often allow for contacts over greater distances, sometimes several hundred kilometers. Weather fronts can enhance the bending effect and also allow for occasional contacts as a result of ducting, in which radio waves get trapped within a layer of cold air sandwiched between two layers of warmer air. When ducting takes place on a grand scale, contacts can sometimes happen over distances of up to about 1500 kilometers.

Ionospheric F layer propagation has occurred on 6 meters. During that sort of opening, you can communicate in much the same way as you can do on 10 meters under similar circumstances. More often, 6-meter ionospheric propagation takes place via the E layer, which tends to ionize in “clouds” at an altitude of around 80 kilometers during periods of sunspot maxima. This effect, called sporadic-E propagation, happens quite a lot over transequatorial paths (paths that cross the earth’s equator) a few weeks either side of the equinoxes, when the sun lies in the same plane as the earth’s equator. Look for transequatorial sporadic-E openings in March, April, September, and October.

More exotic modes of communication, such as auroral propagation and meteor scatter, occasionally manifest themselves here. These modes generally require CW or a synchronized digital mode.

Allocations by Mode

The lowest 100 kHz of the 6-meter band, from 50.000 MHz to 50.100 MHz, is reserved for CW operation only. Most of the CW operation that I’ve heard takes place around 50.090 MHz. You’ll occasionally hear beacon stations on other CW frequencies. You’ll recognize them by their relatively slow, repetitive transmissions with call signs given once a minute or so. The rest of the band, from 50.100 MHz all the way up to 54.000 MHz, is open to all modes of operation that hams commonly use, with the exception of fast-scan television.

Allocations by License Class

All hams except Novices may legally use any frequency in the 6-meter band, subject to the mode constraints outlined above. If you hold an old Novice Class license, you must upgrade at least to Tech before you can use this band.

2 Meters

The slice of spectrum from 144.000 MHz to 148.000 MHz forms the ham radio 2-meter band. It’s one of the most (if not the most) popular ham bands, with the majority of operation done with FM transceivers and repeaters. Hams don’t have to share this band with any other services.

Characteristics

Under most circumstances, 2-meter communications happens in a line-of-sight mode, resembling the bands at higher frequencies. However, tropo can take place here, in much the same way as it does on 6 meters. Ionospheric F-layer propagation has not been observed. Meteor scatter and auroral communications can be carried out, but they’re a little more difficult to initiate and maintain than they are on 6 meters.

Since the “repeater revolution” in the 1970s, propagation forecasts and conditions (and the science that goes along with it) are of little or no concern to radio hams on 2 meters. You might use the band exclusively for repeater communications for years, only to get a rare surprise when a tropo event pops up and you hear someone 800 kilometers away, coming in as if they were located in your neighborhood!

Perhaps the “coolest” mode that hams use on 2 meters—pretty much unknown on the longer-wavelength bands—is earth-moon-earth (moonbounce). To make moonbounce contacts, you’ll need a transmitter that can put out a lot of RF power, preferably the legal limit of 1500 watts PEP, and work in CW or one of the synchronized digital modes. You’ll also need a high-gain directional antenna and a sensitive receiver. And finally, if you live in an RF-noisy location as I do, you might as well forget about moonbounce! The best locations have underground electrical lines and residential lots big enough so that neighbors with rogue electrical appliances can’t ruin reception. You’ll want to check your local zoning laws concerning large antennas, and make sure that none of your neighbors will hate you when they see a matrix of 2-meter Yagis sprout in your backyard.

Allocations by Mode

You may use only CW emission from 144.000 MHz to 144.100 MHz. The range from 144.100 MHz to 148.000 MHz is open to all modes of operation that hams commonly employ, but as on the lower bands, fast-scan television is forbidden because it takes up too much bandwidth!

Allocations by License Class

If you hold an Extra, Advanced, General, or Tech license, you may use any frequency in the 2-meter band, subject to the above-described mode restrictions. If you hold a Novice license, you must upgrade before you can transmit on 2 meters. The prospect of communicating with handheld and mobile radios, along with repeaters, has probably been the greatest factor to motivate old Novices to become Techs!

Beyond 2 Meters

At frequencies above 148 MHz, radio hams enjoy privileges on numerous small slices of the spectrum, as shown in Table 4-1. Once you get up to 275 GHz, you can communicate on any frequency you want, including microwaves, infrared (IR), visible light, ultraviolet (UV), X-rays, and even gamma rays, assuming that you can come up with a transmitter and receiver that will work at those microscopic wavelengths!

Characteristics

Tropo sometimes happens on 1.25 meters and 70 centimeters, and rarely on bands at higher frequencies. Moonbounce has gained considerable popularity on 70 centimeters, and some hams do it on 23 centimeters as well. Satellite links have grown increasingly common in recent years. Repeaters exist on 1.25 meters and especially on 70 centimeters, similar to the ones on 2 meters.

As the wavelength grows shorter, antennas in general grow smaller for a given amount of gain. Large Yagis are practical on 219.000 MHz and above; more exotic antennas, such as helical types, horns, and dishes, appear at 23 centimeters and shorter wavelengths. Hams often combine UHF antennas in arrays called bays—for example, four helical antennas at the corners of a square, or even nine of them at the points of a “Tic-Tac-Toe” matrix! When fed in phase and carefully aligned, such bays can have directionality and gain comparable to a dish.

Allocations by Mode

On 1.25 meters, the range from 219.000 MHz to 220.000 MHz is reserved for fixed digital message forwarding systems. Otherwise, hams can use all known modes throughout all bands, except they can’t legally use fast-scan television (FSTV) on 1.25 meters. In order to use that mode, you have to stay above 420 MHz. Full legal power is allowed except for Novices in their subbands on 1.25 meters and 70 centimeters.

Allocations by License Class

Extra, Advanced, General, and Tech operators may use any frequency on any allocated ham band above 219.000 MHz, subject to the above-described restriction on FSTV. Novices have slices of 1.25 meters (222.000 MHz to 225.000 MHz) and 23 centimeters (1270.000 MHz to 1295.000 MHz). On 1.25 meters, Novices are limited to 25 watts PEP output, and on 23 centimeters, to 5 watts PEP output. However, they can use any legally authorized Amateur Radio mode in those slots.