CHAPTER 8

Ham Operating Basics

If you’re reading this chapter, I assume that you have a ham license, perhaps a new one. If you’ve just joined our “fraternity,” congratulations on getting your license, and welcome to the fray. If you haven’t yet bought or built a radio, doubtless you’ll do it soon, like later today! In this chapter, after a half century as a participant in the Amateur Radio art, I’ll offer a bit of advice concerning how to get the most out of all that new hardware when you get on the air.

Listen, Listen, Listen!

Has anyone ever told you to have big ears and a small mouth, or something like that? When I was a kid, one of my dad’s favorite sayings was “Silence is golden.” Well, sometimes that’s true, but if nobody ever sent out any squeaks or squawks on the ham bands, we’d lose our privileges for lack of use. Nevertheless, good operators spend more time receiving than they spend transmitting. So listen with abandon, and transmit with care.

Choose Your Band

When you power up your radio, you’ll have to choose a band for operation. On VHF, the time of day rarely makes a difference, but on HF it matters a lot. The “upper HF bands” at 20, 17, 15, 12, and 10 meters usually offer better conditions during the daylight hours and in the spring and summer; the “lower HF bands” at 40, 60, 80, and 160 meters usually work better at night and during the fall and winter. (Exceptions happen, of course!) The 30-meter band can go either way, a characteristic that makes that 50-kHz-wide slot especially interesting.

Do you want to have a slow, easy, casual QSO (contact) with someone? Are you planning to work in a contest, or to work DX? Are you involved in an emergency where your operation will take place on a predetermined frequency or frequencies? Do you want to test a new antenna on the band for which it’s designed (or maybe on a band for which it’s not designed, out of sheer curiosity)? Do you want to use CW, RTTY, DigiPan, SSB, FM, or one of those new and exotic modes, such as MFSK or WSJT? All of these factors will affect which band you choose, and where in that band you operate.

If you have a multiband antenna, you’ll hear abundant signals on some bands and few or none on other bands at any given time. But the “spectrumscape” will constantly change!

On a winter night in South Dakota, you’ll almost certainly hear signals on 160, 80, and 40 meters. If anyone is using 60 meters you’ll probably hear signals there too. But go up to 10, 12, or even 15 meters, and you should expect to hear nothing other than receiver hiss and, if you live in a place where radio-noisy electrical appliances abound (as I do), various forms of human-made roaring, buzzing, and popping.

On a fair afternoon in June, and particularly if the sunspot cycle is near its peak, you should expect to hear plenty of signals on 10, 12, 15, 17, and 20 meters, a few on 40 and 30 meters, very few if any on 60 meters, and only locals and regionals on 80 meters. The 160-meter band might host a few specialized traffic nets, but otherwise, you won’t find that band of much use on summer days.

The Contest Conundrum

If you operate on weekends, you’ll often have to deal with contests that will affect your choice of band, frequency, and/or mode. For example, on specific weekends in November, the Sweepstakes contest fills either the digital or voice parts of most HF bands with aggressive operators using high-powered stations and huge antennas. During the daytime, you might find casual communicating or DXing nigh impossible on 20, 15, and perhaps even 10 meters. At night, you’ll encounter the same situation on 80 and 40 meters.

If you want to do some casual operating or DXing or anything else that does not involve contests, and you happen to hit one of the major contest weekends, you can go to a band where contesting doesn’t happen. The 60-, 30-, 17-, and 12-meter bands rarely, if ever, host contest events. On the first full weekend in December, you’ll encounter the 160-meter contest, and in January, there’s a DX contest down there. Otherwise, most weekends will work out all right on that band, at least in the wintertime and at night. And don’t forget that you can always do some hamming on weekdays, too!

Don’t Be a Lid!

When a band gets congested, you’ll eventually come up against somebody who’ll transmit on top of you, insult you, or otherwise act like a jerk. Hams have a term for operators like that: lid. Characteristics of a lid, some of which are merely rude and others of which actually violate FCC regulations, include:

• Failing to ask if a frequency is in use before sending a CQ.

• Sending a CQ despite other hams’ telling you that the frequency is in use.

• Unidentified transmissions of any sort.

• Sloppy sending on CW.

• Profanity or insulting language in any mode.

• Prolonged, incessant “tuning up” or testing on a single frequency.

• Drawn-out, monologue-like CQs.

• Changing the transmitter frequency while putting out a signal.

• Transmitting a signal whose bandwidth exceeds the legal limit for the mode.

• Deliberately interfering with other hams’ QSOs.

• Failing to heed instructions for calling a station when its operator gives specific instructions for calling.

• Failing to yield a frequency to an emergency operation.

• Acting as if you “own” a particular frequency.

No matter how much of a lid someone might be, don’t let his or her bad manners turn you into a lid, too. You might feel a strong temptation to transmit “LID” on CW or say, “Get lost, lid” on the phone. Resist that temptation. Only lids call other hams lids on the air.

Signal Reporting

Whenever you make a contact, you’ll want to know how strong your signal is at the other end. You’ll want to know how you sound, or whether you’re causing splatter or otherwise emitting a signal that’s not state-of-the-art. This curiosity constitutes part of a good operator’s mentality! You’ll also want to tell the operator on the other end how well his or her station is doing at your end.

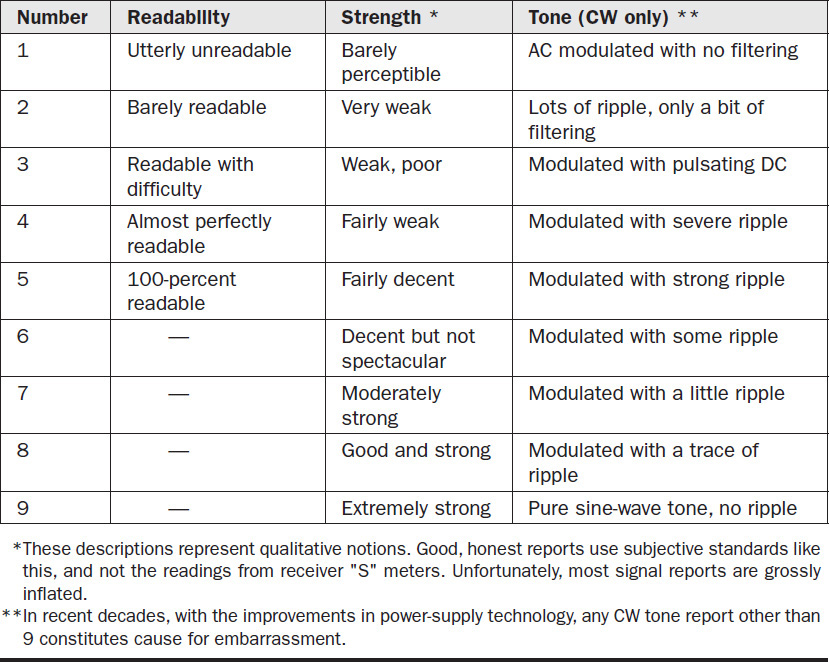

Signal strength reports can vary from qualitative expressions, such as “You’re booming in here, the strongest signal I’ve heard all day!” to quantitative reports that give numbers for readability, strength, and quality of sound or tone. From worst to best:

• Readability numbers go from 1 to 5.

• Strength numbers go from 1 to 9.

• Tone numbers (in CW only) go from 1 to 9.

Table 8-1 breaks down the RST (readability, strength, tone) signal reporting system that ham radio operators use. In voice modes, you can leave the tone number out, even though, arguably, it would prove more useful on those modes than on CW! So you might say, in CW, “RST 579” but in SSB you would say “You’re 5 by 7.”

TABLE 8-1 The RST (Readability, Strength, Tone) System for Signal Reporting

Despite the lack of a tone number in signal reports for the voice modes, you should tell the other operator if his or her voice is distorted, tinny, muffled, or otherwise mutilated. You can use plain language to describe technical things when working in voice modes. For example, if someone says that your mobile FM signal has alternator whine, it means that your vehicle’s alternator is causing trouble with your transmitter (modulating your signal with an audible tone that varies in pitch as your alternator speeds up and slows down). If someone says that your FM signal is full quieting, it means that you’re strong enough to keep the squelch in the receiver completely open so that your signal overcomes the receiver hiss of a partially open squelch.

In CW, the tone number is almost always 9, meaning a pure, steady signal without hum or other modulation that would result from a bad power supply or some sort of unwanted oscillation in one of the transmitter amplifier stages. In fact, the tone number has devolved in the past several decades to the point of irrelevance. Only a primitive transmitter ever puts out a CW tone with quality anything less than 9. If you ever get a tone report of anything other than 9, you had better listen to your signal on a separate receiver, and if a problem exists, get it corrected!

Although CW signals almost always have perfect tone these days, other technical troubles can occur in that mode. Key clicks can mess up a CW transmitter’s signal big time. If a station’s transmitter generates such artifacts so that you hear popping noises above and below the carrier frequency, add a K at the end of the signal report, for example “RST 579K.” Key clicks result from too-fast attack (start) and/or decay (end) periods on code elements. In effect, they amount to CW splatter, and they cause the signal to violate FCC regulations.

If a CW transmitter produces a carrier that changes frequency slightly at the start of each code element, add a C for “chirp,” for example “RST 579C.” If a signal is amplitude modulated by an audio tone like a musical note, you’ll have to use plain language to inform the other operator. Chirp and musical modulation don’t occur often in latter-day equipment, but I’ve heard both problems on the air as recently as 2013. Usually they appear on the signals from DX stations in countries whose people lack good access to modern technologies.

Operating in SSB

On the HF bands, single sideband (SSB) is the most common voice mode. You’ll hear mostly lower sideband (LSB) on 160, 80, 60, and 40 meters, while upper sideband (USB) prevails on 20, 17, 15, 12, and 10 meters. You won’t, or shouldn’t, hear SSB at all on 30 meters.

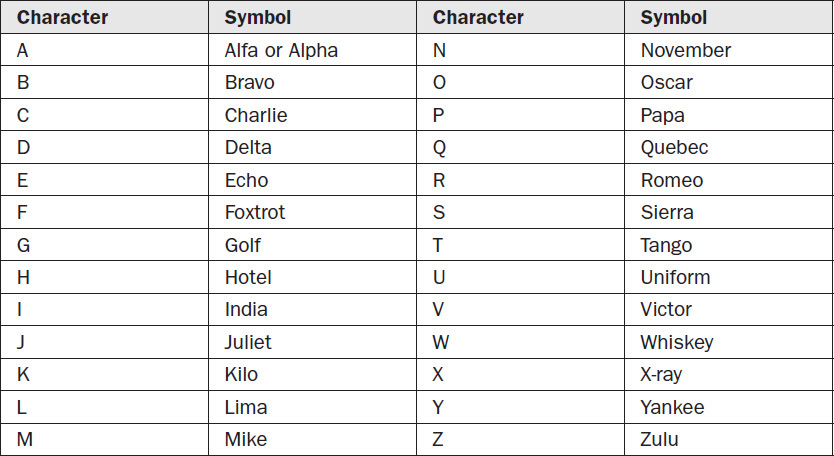

The Phonetic Alphabet

Voice-mode operation offers the convenience of plain-language communication, so it’s more “up close and personal” than digital modes. You can express things without resorting to abbreviations or special signal codes to save time. But once in a while that convenience can turn into a problem, especially under marginal conditions, such as QRM (interference from other stations), QRN (radio noise such as sferics), and QSB (signal fading).

Occasionally, you’ll find yourself spelling out certain words because conditions have grown so bad that the other operator has trouble “copying” you on SSB. For example, if someone can’t get my name straight (Stan), thinking maybe it’s Dan or Sam, I can spell it out for them. But if I say “S-T-A-N,” they might instead hear “F-E-A-M.” Then they’ll be more confused than ever! In situations of this sort, I can use phonetics and say, “My name is Stan: Sierra, Tango, Alpha, November. Stan.” That almost always clears things up.

Despite its advantages, some hams use the phonetic alphabet to an extreme. If the other operator has no trouble “copying” you, then you shouldn’t use phonetics. And once in a while someone will use phonetics in a way that makes them sound almost lid-like: “CQ Delta X-ray,” for example, rather than the correct “CQ DX,” which means “Calling any DX station who wants to have a QSO with me.”

TABLE 8-2 Phonetic Representations for Letters of the English Alphabet

Calling a Station

Imagine that you hear someone calling CQ on SSB, or ending a contact while leaving open the possibility of having another one. Wait until the operator stops transmitting, and then push your microphone button and send his or her call once, followed by “this is” and then your own call twice—without phonetics the first time and with phonetics the second time. For example:

W7***, this is W1GV. Whiskey one golf victor. How copy?

Keep your call short. Speak clearly at a moderate pace. Talk loud enough so that the transmitter’s power or RF output meter kicks up to the proper points. If you need to increase the microphone gain, use the transmitter control; don’t shout. If you need less gain, turn the transmitter control down instead of whispering. Keep the microphone grille facing your mouth at a slight angle, two or three inches from your face.

Once you’ve finished transmitting, wait a few seconds, and if the other station doesn’t respond, transmit your offer again, exactly the same as you did the first time. After that, you’ll know whether or not the other station’s operator can hear you (or wants to talk with you).

Sending CQ

Before you send CQ on any frequency, you should listen for at least three or four minutes to make reasonably sure that no one is having a QSO there. If it looks clear, ask if the frequency is in use, and identify your station, like this:

Is the frequency in use? This is W1GV.

Wait another half minute or so, and if nobody tells you that the frequency is in use, you can go ahead and send your CQ. Here’s how I do it:

CQ, CQ, CQ, this is W1GV.

CQ, CQ, CQ, this is W1GV.

CQ, CQ, CQ, this is W1GV. Whiskey one golf victor.

Standing by!

When I say these things at my leisurely western pace, it takes me 25 seconds. Wait a half minute or so, and then repeat your CQ if nobody answers. Then wait again, call again, wait again, call again, as many times as you like, or until someone answers or tells you to go away!

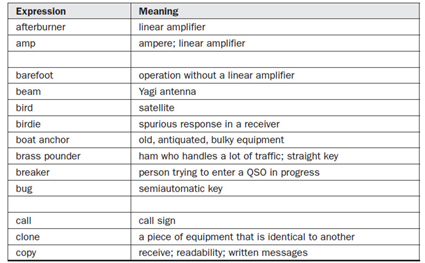

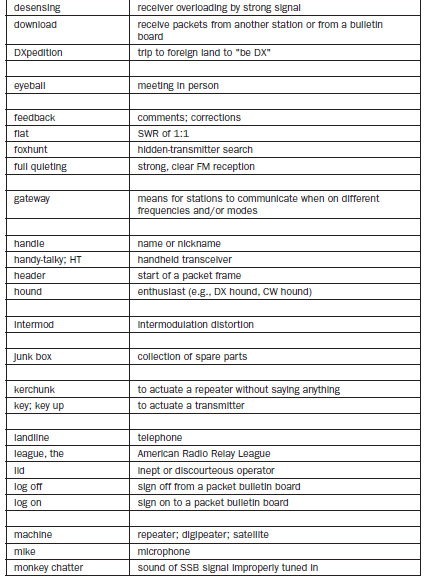

Carrying on a QSO

The length of time that you spend in a QSO depends on the operating environment, as well as your mood. If you’re working a DX station that lots of other hams are waiting to contact, or if you’re in a contest, you won’t get personal and the whole contact will take a few seconds. If you’re “chewing the rag,” however, you might go on for hours! But even when you are involved in a long, conversational QSO, don’t get into extreme monologues, any more than you would in a face-to-face conversation (also known as an “eyeball QSO”).

In any case, you must identify your station at the end of the contact, and at least every 10 minutes during the course of the contact. If your QSO is taking place for the benefit of a third party and it also happens to be an international communication, then you must also identify the other station. Various other rules exist for special situations. The ARRL operating manual covers some of these, but if you want the whole story straight from the lawmakers’ pens, you should get a copy of the FCC regulations for radio hams.

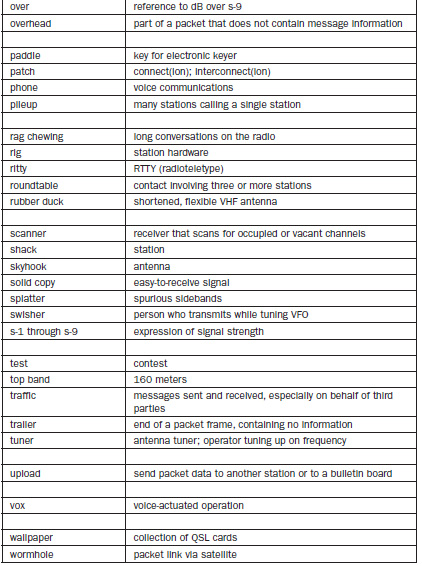

TABLE 8-3 Some Voice-Mode Expressions in Ham Radio Jargon

Ending a QSO

In SSB, ending a contact works like ending a face-to-face or telephone conversation, with the exception of the station identification requirements. You might want to say “73,” which means “Best regards!,” and some other form of farewell peculiar to hams, such as “See you later on down the log.” If the other operator is of the opposite gender, you might also throw in “88,” which means “Love and kisses” in a playful sort of way. Listen around on the SSB portions of the HF bands for a while, and you’ll gradually grow familiar with the jargon and quirks peculiar to this hobby!

Operating in FM

Most ham FM operation takes place on the VHF and UHF bands, especially 2 meters and 70 centimeters. Of that activity, nearly all goes through repeaters. While FM is a voice mode like SSB, you’ll behave differently on an FM repeater than you would in an HF SSB environment.

Accessing a Repeater

In the 1970s when I first got active on FM repeaters with a mobile 2-meter rig, I could almost always find a repeater and access it when I could hear it. The radio would scan the band between limits that I could preset, and then search for an occupied channel. On one occasion, I accessed a repeater and helped a family whose car had broken down at night in the country. Cell phones didn’t exist then, so my communication through a repeater saved that family a lot of tedium and grief.

Today, if you can hear a repeater, you probably won’t be able to use it unless you know the subaudible tone frequency for access. (Of course, we have cell phones now too, so that family probably would not need a ham like me in a similar situation now.) The tone is a steady sine-wave audio note that modulates the FM carrier at a frequency below the standard voice passband. You can obtain the tone frequency for a repeater by joining the club that operates it, or by looking it up in a database, such as the latest edition of The ARRL Repeater Directory.

You’ll also have to know the split for the repeater that you want to use. That’s the difference, either negative or positive, between the repeater’s input and output frequencies. For example, a repeater might use 146.34 MHz as its input frequency and 146.94 MHz as its output frequency. That means it “hears” on 146.34 MHz and “speaks” on 146.94 MHz. In that case, you’ll set your radio to transmit on 146.34 MHz and receive on 146.94 MHz. Hams call that frequency combination “34/94.” Because you transmit on a frequency below the one on which you receive, hams call that split “negative” (specifically, −600 kHz). If a repeater transmits on 147.00 MHz and receives on 147.60 MHz, then you’ll want to set your radio to transmit on 147.60 MHz and receive on 147.00 MHz. Users of that repeater would call its frequency combination “60/00.” Because you must transmit on a frequency above the one on which you receive, you call that split “positive” (specifically, +600 kHz).

Initiating a Contact

On any repeater, you won’t hear anybody send CQ unless they’ve never used a repeater before (or they’re a non-ham who has gotten hold of a ham radio set). If you find a repeater and nobody is using it, and if you have your radio tuned to access it, you can send your call and then say “listening.” That’s the equivalent of CQ on a repeater. So, for example, as I roll down a Wyoming road on some crisp February afternoon, I might find a local repeater and, if no one is using it and I know the subaudible access tone frequency, say simply “W1GV listening.”

Calling a Station

If you hear someone say that they’re listening on a repeater, feel free to call them and have a contact! Say that station’s call once, then yours once without phonetics, and then again with phonetics, just as you would do on SSB to answer a CQ.

In a repeater environment, “breaking in” is usually okay unless the ongoing communication has a priority or is for an emergency. When one of the stations ends a transmission, say your call once, clearly and without phonetics. If the other operators can hear you and don’t mind your breaking in, they’ll either call you straightaway, or else ask “Who’s the breaker?” or something like that.

Carrying on a QSO

On FM, contacts proceed like they do in ordinary conversation, with the exception of the identification requirements and some technical jargon peculiar to radio hams. Keep your transmissions short and to the point. Remember that repeaters exist not only for convenience, but also (and more importantly) to serve in emergencies. You never know when someone will encounter a repeater and urgently need to use it. Leave lots of openings for such folks!

On a repeater, you should wait a few seconds after the other station finishes a transmission, and then start yours. Leave a few seconds for “breakers” who might want or need to join you.

Many repeaters have a timeout function. A repeater will keep putting out the carrier for a second or two after someone finishes a transmission. Then it will drop out (stop transmitting altogether). You’ll see this event as a dive in your receiver’s S-meter reading. It’s a good idea to let a repeater drop out after the other station ends a transmission, and then start yours. If two hams involved in a repeater QSO don’t let the machine drop out periodically, it might time out after a while anyway, bringing the QSO to an unplanned end.

Operating in CW

Since the elimination of the Morse code requirement for obtaining a ham license, CW operation has declined. Even so, a significant number of hams, myself among them, still use that mode for enjoyment. I can assure you that CW, for someone who really likes it, plays the role of an art, a science, and an addiction!

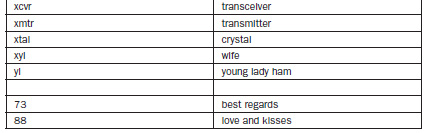

Abbreviations for CW

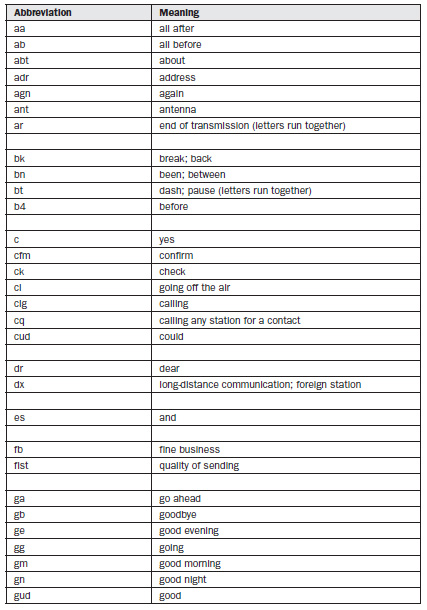

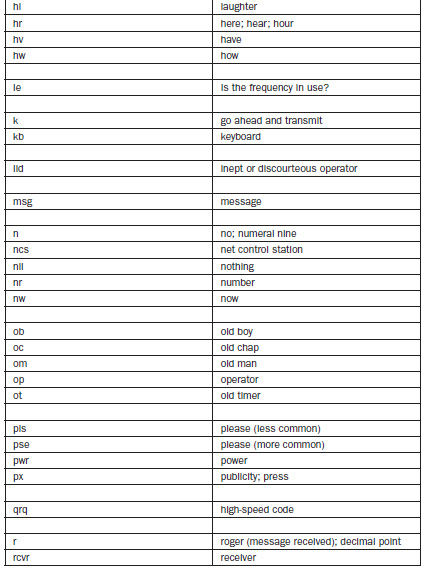

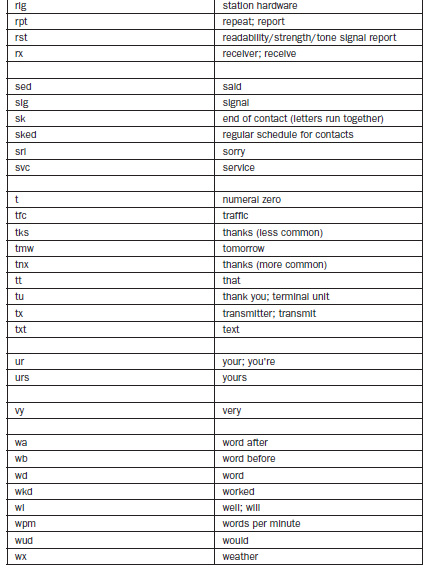

All experienced CW operators use abbreviations to reduce the number of characters that they have to send. These abbreviations resemble the jargon used in cell-phone texting, and in some cases, the two are identical. If you operate CW for a while, you’ll grow familiar with them. Table 8-4 shows some of the most often-used ones.

TABLE 8-4 Abbreviations used in CW operation. (For Q signals, see App. B.)

Calling a Station

Imagine that you hear a station calling CQ or ending a contact, and you want to start a QSO. Send the other station’s call once, followed by yours once, twice, or three times, depending on how well you think the other operator will hear you, and depending on the length and “CW friendliness” of your call sign. Send at the same speed as the other station, or maybe a little slower. If the station is sending way too fast for you, consider skipping that station and trying another one, unless you want to contact it badly (a rare DX or a special events station, for example).

Sending CQ

If you want to start a contact but don’t hear anybody else sending CQ or ending a contact, you can send your own CQ after asking if the frequency is in use. I make that query by sending “QRL?” followed by a pause and then “DE W1GV.” If the frequency is occupied, you’ll probably hear somebody send the single letter C (meaning “Yes”). If no one tells you that the frequency is in use, send your CQ at the speed you’d like to go in a QSO. Here’s how I send a CQ under most conditions:

CQ CQ CQ DE W1GV

CQ CQ CQ DE W1GV

CQ CQ CQ DE W1GV W1GV W1GV

K

Avoid sending long CQs. If you do that, QSO candidates will get bored and tune off your frequency after a while. Would you want to hear me send the following extreme CQ?

CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ

CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ

CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ

CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ

DE W1GV W1GV W1GV

CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ

CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ

CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ

CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ

DE W1GV W1GV W1GV

CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ

CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ

CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ

CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ CQ

DE W1GV W1GV W1GV

K K K

You’d never listen to such a broadcast all the way through from a plain old stateside station like mine, would you?

After you’ve finished a CQ, wait for a minute or two and then try again. Slowly tune your receiver a kilohertz or two up and down while leaving your transmitter frequency alone. Most radios have receiver incremental tuning (RIT) intended for this sort of situation.

Carrying on a QSO

The length and content of a CW QSO depends on the circumstances. In DXing or in a contest, it’ll comprise only a signal report along with other essential information, such as your location and perhaps some contest exchange data. If you want to have a long CW conversation and the other station does too, you can keep at it all day, or as long as the band will stay open for you. Remember the identification requirements (at least once every 10 minutes), keep your transmissions down to reasonable length (a couple of minutes each time), and have fun!

Ending a QSO

When you’ve had enough of a CW QSO or external circumstances force you to stop, wish the other station “73” (Best regards) or maybe “88” (Love and kisses) if the other operator is of the opposite gender and you know that she or he won’t be offended by such informality. Then you can send the other station’s call followed by your own, and finally the letters S and K run together (di-di-di-DAH-di-DAH).

Operating in Non-CW Text Modes

You’ll have an easy time operating in the non-CW text modes (RTTY, PSK31, MFSK, AMTOR, and the like) if you have CW experience. If you’re not a CW operator or you are new to ham radio, read the previous section and then monitor a few QSOs on one of the non-CW digital modes to get the gist of how contacts proceed. Get the computer, the interface, and the software, and watch people send CQs, answer them, and work multiple contacts, and whatever else they do.

Tutorial Mode

I recommend PSK31 for learning how to use non-CW text in your communications. The signals are easy to find on the bands, you can almost always find a few if a band is open, and many of the people who use that mode are beginners, poor typists, or Elmers looking to help newcomers along. In addition, the tuning-aid display for PSK31, known as a waterfall, is easy and intuitive to use—and a whole lot of fun to watch and “tweak”!

Ears versus Eyes

Despite the similarities in operating procedure, a few technical differences prevail between non-CW digital modes and the good old Morse code, and these differences will affect the way you use your radio and associated peripheral equipment. For one thing, with the non-CW modes, you read the other person’s stuff and send yours on a keyboard, rather than listening to audio tones and manipulating a keyer paddle or straight key. (Some CW operators use decoding software and keyboard keyers, but die-hards like me still do it the old way.) You can carry on a non-CW digital text QSO in a noisy room without headphones; on CW you’d need headphones in that same noisy room. And of course, in the non-CW digital modes, you don’t have to know all the code symbols; in old-school CW, you need practice to gain proficiency.

Relative Frequency

The second distinction between CW and non-CW digital modes lies in the choices of relative frequency during communications. On CW, you can call another station on a slightly different frequency and the other party will likely hear you. In fact, rare DX station operators often prefer that you call a little above or below their frequency, not right on top of them. However, in non-CW text modes, both stations nearly always carry on their QSO on precisely the same frequency. In other words, the two signals are usually zero beat with each other.

Break-In (or Not)

Another difference between old-fashioned CW and the digital text modes is the fact that, with the digital modes, you can’t operate full break-in as you can do with CW. The Morse code is a mark-only code; spaces are actual carrier gaps, during which your QSO partner can break in on you if your radio has the capability to hear during those gaps. In the non-CW digital modes, every transmission needs a continuous carrier; no gaps exist. The only way to obtain full break-in operation in PSK31, for example, would involve split-band duplex (in which one station sends on, say, 14.071 MHz and listens on 21.071 MHz, and the other station sends on 21.071 MHz and listens on 14.071 MHz). Most non-CW digital text mode operators don’t want to go to the trouble to set up their rigs to work that way.

Tuning in a Signal

Yet another distinction between CW and non-CW digital text involves the tuning procedure. With old-fashioned Morse code, you can hear a signal and decode it in your head, no matter where it happens to show up in your passband. You might prefer a certain range of audio frequencies, such as 600 Hz to 700 Hz; but if your radio can hear everything that produces beat signals between 500 Hz and 1000 Hz, then you can copy that stuff too. With PSK31, RTTY, MFSK, and similar modes, you must tune your receiver precisely so that the mark and space tones fall within the narrow audio passbands of the decoding software.

Contesting

On most weekends, one or more of the HF ham bands hosts a contest. Some contests are organized by region or locality; others involve specialties, such as CW or RTTY or 160 meters only. Contest exchanges vary in complexity; some require only a signal report and the ARRL section in which you live, while others require contact numbers or station data along with the signal report and your location or section. All contests encourage you to make as many contacts as you can, in as many different places as you can, within a set period of time, usually 24 to 36 hours.

You Be the Prey

When you have a well-engineered antenna system and a full-legal-limit amplifier, you’ll be able to “run a frequency” in a contest, sometimes for quite a while. It’s fun to act as “game in a hunt,” especially if you make for “tasty game”! (I live in a sparsely populated ARRL section, a characteristic that makes me an especially desirable target in contests.) When you have a “big rig,” however, don’t act like a bully with it. Listen for a couple of minutes and then, if you hear nothing, ask if the frequency is in use before you start sending CQs.

In CW, you can send “CQ TEST,” and people will know that you’re looking for QSOs in whatever contest prevails at the time. Send at a reasonable speed, such as 18 to 20 WPM. That way, you won’t scare away potential contacts. While you might impress people by zipping along at 35 or 40 WPM, such show-offishness will spook less experienced operators, even if your signal is strong enough that it would make for easy copy otherwise. In SSB and other voice modes, say “CQ CONTEST” three times, then your call sign once without phonetics, then once with phonetics, and then say “standing by.”

Once you get hold of a certain frequency, you can stay on it until it “grows stale” and you don’t get many calls anymore, or until the band goes out, or until you collapse from exhaustion, or until the contest ends, whichever comes first. But keep in mind the fact that, in most contests, you’ll get more points on the average if you make them on as many different bands as possible, and not all on one or two bands. (A few single-band events do exist, such as the ARRL 160-meter and 10-meter contests, held every year in December.)

You Be the Hunter

If your station has modest antennas and/or lacks a full-legal-limit amplifier, you’ll find it difficult to “hold a frequency” in a contest. You can always try to capture a frequency, sending “CQ TEST” or “CQ XXX” (where XXX stands for the contest in question, such as “SS” for “Sweepstakes” or “FD” for “Field Day”), but unless you have a powerhouse station, you should expect to make more contacts if you seek out and search for stations sending CQ, and then respond to them.

In CW, transmit at a reasonable speed so that you need send your call and exchange data only one time. If you send everything at 18 WPM once and the other station gets it, you’ll get at least as many contacts over time as you would get if you sent everything at 36 WPM twice. You might even go faster in effect at 18 WPM because it takes extra time whenever the other station has to ask you to repeat something. I’m lucky in CW contests and other CW competitive operating venues because my call sign is easy to copy on CW, and I hardly ever have to repeat it. For signal reports, always send “5NN” which is CW shorthand for “599,” even if the other station has a rotten signal.

In SSB or other voice modes, speak clearly at a moderate pace using phonetics when necessary. Stick with the standard phonetics as listed in Table 8-2. When ending a transmission, say “Over?” as if asking a question. To confirm receipt of the other station’s data, say “QSL.” If you must ask someone to repeat certain data, request in plain language that they send it again.

Working DX

One of the most intriguing aspects of ham radio is the fact that you can communicate, independently of humanmade infrastructures, with people all over the world. Hams call this practice DXing, where “DX” stands for “distance.” But DXing involves more than maximizing the length of a communications path, which can’t exceed 20,000 kilometers (half the earth’s circumference) in any case. True DXing means working hams in lots of different recognized nations, no matter how near or distant. Many hams have confirmed contacts in more than 100 countries, thereby qualifying to join the ARRL’s DX Century Club, and some hams have made QSOs in more than 200 countries.

Choosing a Band

When you want to make DX contacts on HF, you’ll have the best luck if you choose the optimum band. As a general rule, most daytime DX happens at 20 meters and shorter wavelengths, while most nighttime DX happens at 30 meters and longer wavelengths. But exceptions occur, notably on 30 meters and 20 meters. Sometimes you can work great DX on 30 meters during the day, and sometimes you can do it on 20 meters or even 15 meters at night.

Because spring and summer offers days with more sunlit time than dark time, the bands at 14 MHz and up will more likely yield good DX during those months. Conversely, because autumn and winter have days with more dark time than sunlit time, the bands at 10 MHz and below will usually work better for DX during those months. Usually. Exceptions occur, sometimes with spectacular openings on frequencies you wouldn’t think could produce any contacts at all, let alone for DX.

After taking advantage of the above-mentioned guidelines as a starting point, you should listen on all the HF bands, whether it’s winter or summer or day or night, and find the one with the most evidence of DX activity. You might also base your decision on other factors, such as the general noise conditions at your location (14 MHz has horrible humanmade noise at my QTH, while 10 meters has almost none). You can’t work stations that you can’t hear, and humanmade noise from rogue electrical appliances has proven the bane of myriad DXers’ lives.

Looking for DX

The classic signature of a DX station’s presence is a so-called pileup of stateside (United States) stations calling, usually sending their own call sign once or twice, and nothing else. For example, if you keep hearing “W1GV” over and over at intervals of about a minute, you can have confidence that I’m calling a DX station in a pileup, especially if you can also hear numerous other stations sending their own call signs at intervals of about a minute. You might hear the DX station’s signal between bursts of stateside calls if it’s using the same frequency as the stations calling. Listen carefully!

In a massive pileup, so many stations might call the DX that you can’t separate them. On SSB it will sound like a great unruly crowd of people shouting (which, in fact, it is); on CW, it will sound like a pack of wild animals from some alien planet, howling in tones of diverse pitch. If the pileup grows extreme, some rudeness will emerge, and you’ll hear people sending their call signs repeatedly and continuously. On SSB, you might hear snide comments or inane questions, such as “Screw off!” or “Who’s the DX?”

Single-Frequency Mode

In most cases, DX stations will respond to calls on, or very near, their transmitting frequency, a practice called single-frequency mode.

If you’re working SSB and you want to work DX in single-frequency mode, tune in the DX signal until the voice sounds natural, and then make certain that your radio is not set for any sort of incremental tuning, such as receiver offset (also called clarifier) or transmitter offset. Then, when you respond, the DX station will clearly hear you because your station’s suppressed-carrier frequency will be zero beat with the DX station’s suppressed-carrier frequency.

On CW, you can respond near the DX station’s frequency, say 200 Hz to 500 Hz higher or lower, and consider the mode as single-frequency. Some DX stations dislike getting calls exactly on their frequency, so you shouldn’t zero beat the DX signal. You can also listen to the pitches of the signals from operators calling the DX, and avoid sending your call exactly on any of their frequencies. That way, the DX will more likely hear you when you call along with other stations simultaneously.

In PSK and other non-CW digital modes, you should always respond to a station precisely on its frequency, whether or not it’s DX. That’s because most operators in those modes use simple computer programs and interfaces that automatically send on the frequency to which they’re tuned, and lack the capability to search for anybody who might call them on some other frequency. If you respond on another frequency, even a slightly different one, the other operator will probably miss the fact that you’re calling.

Split-Frequency Mode

When a DX station operates in split-frequency mode, its operator wants you to call on a significantly different frequency from the one on which she or he is transmitting. Ideally, the split should be large enough so that the receiver passbands of the DX and calling stations don’t overlap even slightly. That way, you’ll always be able to hear the DX station when it transmits, even if dozens of other stations happen to accidentally call at the same time. Splits rarely exceed a few kilohertz, however.

When a DX station, or some other rare station such as one involved with a special event, wants to work in split-frequency mode, it will send something like “UP” or “UP 1” on CW, and give instructions in plain language on SSB. You can take “UP” to mean “Please respond a kilohertz, or two, or maybe three, above my frequency.” Of course, “UP 1” means “Please respond approximately 1 kHz above my frequency.”

When You Are the DX

For the adventurous spirit, nothing in ham radio can surpass the thrill of playing the role of prey in a massive DX pileup by going on a so-called DXpedition. Go to a different country, preferably an exotic one, and operate from there! Then you can have a great time working thousands of stations at a pace limited only by your operating skill. Once you get on the business end of a pileup, you’ll find out why rare DX stations sometimes behave in strange and seemingly neurotic ways. You’ll gain a good deal of operating savvy in a hurry.

If you want to go on a DXpedition, you must make arrangements for operating privileges in the country you choose. If you think that your government throws a lot of red tape in your way, wait until you deal with a foreign country, especially one that’s not entirely friendly to yours! You might have to get a special license, and even obtain permission to carry your equipment into the other country. You should also make sure that you do everything according to the rules of your own country.

Rag Chewing

Sometimes the competitive aspect leaves even the most hard-bitten contesters and DXers, and they want nothing more than to carry on a casual conversation with another ham. Other hams prefer the slow life in general, and use the radio as a form of entertainment (or loneliness mitigation). In ham radio, general conversation, especially the long-winded sort, is called rag chewing. You can chew the rag on CW, RTTY, PSK31, MFSK, or any other mode, but most of that activity happens in the less competitive portions of the SSB subbands.

Use common-sense judgment when choosing topics to talk about. If you want to discuss politics with a citizen of another country, for example, you’re entering perilous territory. In fact, I personally avoid political discussions in ham radio. If you want to talk about football with a Green Bay Packer fan (such as myself), you might get razzed if you root for someone else, but you won’t spark World War III. If you want to talk about the weather or some other mundane topic, of course, anything goes, except spreading stuff like false hurricane warnings.

Don’t make a habit of chewing the rag on repeaters. Those machines should remain available for priority and emergency communications. While rag chews on repeater are not unknown, they take place only when a repeater would likely see no use otherwise; and the rag-chewers are always ready to allow breakers to take over when they need the repeater for something important.

Warning! Amateur Radio is intended for non-profit activities only. You can’t legally use ham radio for conducting business. For example, you shouldn’t negotiate a real estate contract on 20-meter CW (or any other ham band). As a general rule, stay away from anything having to do with making money for yourself. Legal issues aside, this hobby is supposed to provide a distraction from workaday stuff anyway, isn’t it?

Operating with QRP

If you like challenges, low-power operation (called QRP after the Q signal for reducing power) will provide you with plenty. I enjoy this aspect of ham radio because it gives me a chance to test new antenna designs and sharpen my operating skills. I run 10 watts output on CW and 7 watts output on PSK31, my two favorite operating modes, from my home station.

What’s True QRP?

No binding definition exists for QRP, but hard-core, low-power aficionados say that you must keep your output to 5 watts or less to qualify as a full member of the QRP fraternity. Some hams run a lot less power than that! The abbreviation “QRPp” stands for an RF power output of 1 watt or less. Believe it or not, with a good antenna system and excellent propagation conditions, you can work stations on the other side of the planet with QRPp, especially on CW. The best bands for this activity are 12, 10, and 6 meters. However, some people have made QSOs over considerable distances using less than 1 watt all the way down to 1.8 MHz.

Technical Advantages of QRP

When you operate QRP, you can use battery power to run your station, and your batteries won’t be five times as heavy as you are. Today’s all-solid-state radios draw almost no current on receive, and not much on transmit if you scale your power down to a few watts. A deep-cycle marine battery with 35 to 50 ampere-hours of capacity can last for a full day or two with a QRP station comprising a radio such as the TenTec Argonaut or equivalent.

If you have a substantial radio but can scale it down to a few watts with an RF output control, QRP offers the advantage of “no-worry” continuous carrier output for the non-CW digital modes, such as PSK31, RTTY, or MFSK. With my Icom IC-746 Pro cut back to 7 watts output, I need not fear overstressing the final amplifier, even if I transmit all day long.

With QRP, you can get away with receive-grade capacitors and inductors if you want to build antenna tuners. You never have to worry about the risk of overheating or arcing in your transmission line or tuner components, no matter how high the SWR gets. If you want to force-feed an antenna whose feed line comprises small-diameter coax with a 20:1 SWR, go ahead! You won’t roast anything with 5 watts, no matter how high the SWR gets.

Finally, you never have to worry about RF exposure with true QRP of 5 watts or less. Guidelines suggest that RF fields with effective radiated power (ERP) levels that low don’t constitute an issue at all. In addition, you’ll rarely have angry neighbors coming to your door demanding that you stop interfering with their cell phones, computers, television sets, refrigerators, toilet paper dispensers, or whatever. Unless, of course, the mere sight of your antenna spooks someone— unfortunately a not altogether uncommon occurrence.

Personal Rewards of QRP Operating

After years of QRP operation, I’ve evolved to enjoy the challenges, not suffer from the limitations! If you have a stacked pair of 4-element Yagis on 20 meters, one at 60 feet and the other at 120 feet (as W1AW did when I worked there in the late 1970s), along with a full-legal-limit amplifier and a top-of-the-line transceiver, you can almost always work anything you can hear. You don’t need a lot of operating skill to crack a pileup with a station like that, although if you act rude, your chances go down. Brute force makes the world small.

With only 10 watts of output on CW or 7 watts on PSK31, however, I find that I have to use all my faculties to work DX on a reliable basis. But if I do keep my operating skills sharp and use every trick I know, I can sometimes beat “big guns” in a direct faceoff! When that happens, I recall one of the reasons why I got into this hobby, and why I stick with it. Wiles make up for weakness.

When your station can’t dominate a frequency or a band, you must pay attention to technical issues, such as antenna design, propagation quirks, receiver passband settings, transmitter frequency offset (as opposed to receiver incremental tuning or RIT), and the fine points of operating etiquette. It’s fun to let powerhouse stations contact a DX station or special event station one after another, listen to them snare their prey for a few minutes, and then, like a mouse between the feet of an elephant herd, snag a piece of that game for your log—but only because you’ve done your homework.

Emergency Preparedness

Ham radio justifies its existence when catastrophes wipe out humanmade infrastructures. Amateur Radio operators can provide communications when all other technologies fail. If you’re interested in getting involved in emergency preparedness using Amateur Radio, and assuming that you have a license, here’s what you should do to start:

• Equip your station so that it can run from emergency power for a long time. You should have a generator with plenty of fuel on hand, batteries, and spare batteries, or a stand-alone solar or wind energy system.

• Acquire a portable 2-meter FM transceiver at the very least, and if possible, a dual-band FM radio that works on 2 meters and 70 centimeters. If you can add mobile capability, so much the better; if you can add HF coverage, you’ve got the best.

• Contact the ARRL’s Amateur Radio Emergency Service (ARES) and tell them that you want to get involved, and would like specific instructions. You can find them on the Web at www.arrl.org/ares.

• Get in touch with the officers of your local Amateur Radio club and ask about their emergency preparedness programs. If they have none, consider starting one up yourself.

• Get a copy of The ARRL Operating Manual and read the chapter on disaster, public service, and emergency communications. I defer to the ARRL in this category; no one knows more about the public-service aspect of ham radio than they do.

• If you’re not already an ARRL member, join up!