CHAPTER 4

Britain at risk: accountability and quality control in disaster management

Introduction: The ‘Herald’ disaster

For the past two and a half years, since the sinking of The Herald of Free Enterprise in March 1987, I have been studying Britain's arrangements for the prevention, management and response to peacetime disasters. The Herald disaster contained crucial factors which should have alerted government that something was critically wrong with its perception of its own responsibilities in disaster management.

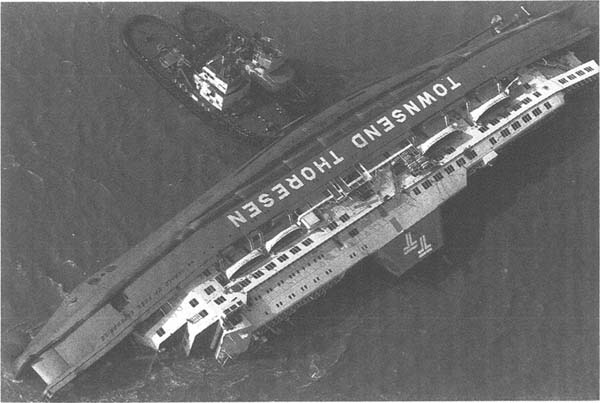

At approximately 1800 hours on 6 March 1987 the Herald of Free Enterprise, a roll-on/roll-off (ro/ro) passenger ferry carrying about 459 passengers commenced her ill-fated voyage from Zeebrugge in Belgium to Dover in England. About twenty-eight minutes later, after passing the outer wall of Zeebrugge harbour, the ferry capsized (Figure 4.1). The immediate cause of the disaster was that the Herald went to sea with her inner and outer bow doors open (Cook 1989).

One hundred and ninety-three people died at Zeebrugge. The disaster was of international proportions; yet there was no central unit to deal with its national or international ramifications. But more serious–when one considers the chain of disasters which followed–was that the Herald's sinking was a disaster of negligence in company management, and the lack of statutory control and proper safety monitoring by government. Most of this had been known by government for years yet no action had been taken.

It is my proposition that in assessing the management of disasters, the same criteria should be applied to government as to the top management of any

FIGURE 4.1 The capsized Herald of Free Enterprise ferry outside Zeebrugge harbour, Belgium, just after commencing its voyage to Dover, England, on 6 March 1987 (Press Association)

national or international firm. If a company does not perform satisfactorily its directors must shoulder the responsibility. Company directors of the P&O European Ferries (Dover) Ltd., (formerly Townsend Car Ferries Ltd.) are currently under threat of prosecution for alleged manslaughter (see recent developments below). Surely the best case for a disaster agency independent of government is that it would not retain civil service immunity, knowing that it would ultimately be judged on its performance, just as management must come to be.

Thus, if one assesses government's approach to disaster planning two and a half years after the disaster at Zeebrugge, the situation still exists in which neither the Home Secretary nor his emergency planning unit has initiated a clear statutory direction about the funding or the training programmes which could lift Britain's approach to modern disasters into the twentieth century. Their laissez-faire approach to a mounting catalogue of civil emergencies has both increased the likelihood of their happening and of perpetuating long term damage to the human beings affected by them.

I would like to explore the Herald tragedy briefly as a basis for this discussion of audit and accountability, bearing in mind that the same exercise could be run on most of the disasters which followed.

In 1982, after the passenger ferry European Gateway capsized following a collision near Harwich, serious design faults were identified which rendered all ro/ro ferries inherently unstable. This ferry and The Herald of Free Enterprise were owned by the same company. Despite massive evidence of instability the Department of Transport allowed ro/ro ferries to continue to sail. As a result of that accident the Formal Investigation declared, ‘The Company and ships' Masters (of Townsend Thoresen/P&O) could be considered negligent (as a) direct result of “commercial interests”’.

One would have expected the Department of Transport to have ordered immediate modifications in the ferries' design and to have monitored Townsend Thoresen/P&O's safety performance under the severest of codes, particularly with commercial interests at stake. This did not take place. Indeed, government departmental inspectors have been heard to defend their lack of action by quoting the cost to commercial industry of making urgent safety modifications. It is this peculiar ambivalence which has provoked the calls from many experts for an independent disaster agency and safety inspectorate.

When the Herald sank, much was made of the Herald's bow doors having been left open. It is very likely that those members of the public who cross the Channel today believe that this was the only reason for the capsize and immense loss of life. In fact, structural instability was and is the primary cause of the disaster. The Formal Investigation (1988) of the Herald's sinking emphasized that another capsize could occur at any time and that this could only be remedied by subdividing the vehicle decks with permanent bulkheads accessed by doors. It further declared that in the event of a ferry colliding with a fixed object, another vessel, or even a jetty, the ship could roll over and sink in as little as three minutes. It concluded:

‘Immediate consideration should be given to phasing out vessels … unless they meet or can be modified to meet, at least, the 1980 standards. If they do not meet them and cannot be so modified, a finite and short term should be put on their lives.’

Such immediate consideration has not been given. No statement has been made about modifications or the phasing out of vessels. The public, if it understood the dangers, would have every right to think that those within the Department of Transport who should be monitoring their safety are either on the way to the club or are more concerned about commercial interests than about them.

Incidentally, the Formal Investigation (1988) did not just stop at structural instability in its list of concerns. Other identified hazards were trimming ships’ bows in order to lower the vessel for unloading, not providing warning lights on the bridge, having inadequate numbers of lifeboats improperly sited, moving crews’ positions on ships for commercial reasons so that they did not know the drills of their safety stations, not marking children's lifejackets, not keeping passenger lists, thus overloading ferries, making false entries in official log books, not providing side exits for escape routes, not providing means of escape from below bulkhead decks, not providing lockers on upper decks with ladders, torches etc., not providing illumination for escape, and finally–and perhaps firstly–the failure of management to accept or take responsibility for its ships.

I have spent some considerable time on this disaster for several reasons. If one is concentrating on quality control or audit with regard to all phases of disasters, one must also ask who in government is setting out the criteria. A Formal Investigation declared the directors of P&O negligent on two occasions when they did not protect their crew and passengers. Is it not fair to turn to Government, when it took no action after the sinking of The European Gateway in 1982, thus contributing to the sinking of the Herald in 1987, and apply the same rigorous standards of quality control to their perception and management of disasters? I would argue that it is not only right, but essential so to do.

At a conference on disaster prevention which was held at the University of Bradford in September 1987 some members of the statutory services were heard to mutter, ‘Prevention of disasters … nonsense, one can't prevent them… they just happen.’ I submit that this is rot. Whether or not a disaster prevention unit at a university or polytechnic can make a significant contribution to this process is open to argument, but one thing is certain. The Herald disaster was preventable; the King's Cross fire disaster of November 1987 was preventable; the Hillsborough football stadium disaster of April 1989 was preventable and so were most of the others of the past few years.

Quality control and civil disasters

What are some of the elements of quality control which should be applied to Government's approach to civil disasters?

(i) The first is an open and frank discussion with contributions from all those playing any part in the planning for, prevention of, or response to disasters. Essential to this process is the involvement of those who have experienced disasters, either in the capacity of workers or victims. Secrecy in planning is counter-productive and leads to suspicion. It is astonishing how much of the process of planning for emergencies is done under a ‘secret’ label. The public should have access to all such plans. They should be published and open to both criticism and discussion. Bearing in mind that as recently as one year ago, Lord Ferrers, Minister of State at the Home Office, wrote that he did not wish to open up the questions of peacetime emergency planning ‘to public debate’, it is not surprising that so many in the field have felt frustrated and angry. It is a measure of the Government's inability to read the growing pressure which is building up among many members of the statutory services, emergency planners, the voluntary agencies, and most importantly, the victims, that a flood of material is being released to the press, simply because they have been denied the proper channels for open discussion.

(ii) Advice should be sought from all those with greater experience, both nationally and internationally. Thus, before any Review of Civil Emergency Planning was published government should have brought in experts from units throughout the world whose skills could have improved our planning and response.

(iii) The performance of all participants, including civil servants forming disaster programmes, should be assessed by an independent group of disaster experts. Personal or departmental defensiveness has no place when dealing with the vast potential human risk which disasters can cause.

(iv) A clear statutory duty should be laid down which allows all agencies and individuals to plan equally for peacetime and wartime disasters.

The review of arrangements for civil emergencies

On 30 June 1988 F6, the then Emergency Planning Division of the Home Office, issued a ‘Civil Emergencies Consultation Paper’ (Home Office 1988) in order to cull the views of some of those working in the field. The document itself raised important questions, even though it chose not to address disaster prevention or how to make management responsible for safety measures.

It was anticipated by many of those organisations and individuals who responded that their papers would be published before an open discussion took place. This was essential for two reasons:

(i) Each person taking part in a conference on the reorganisation of emergency planning was entitled to know the views – based possibly on a wider or different experience – of other experts, and to consider them before attending such a conference.

(ii) Without such publication it was open to those within the Home Office's emergency planning unit to choose the slant which it wished to present to those attending the conference. This may well not have been the unit's motive, but once an open forum was denied this was a plausible conclusion to draw.

The Easingwold Conference on civil emergencies took place in November 1988. Its attendance was limited only to the members of statutory agencies and to representatives of only two voluntary organisations: the Women's Royal Voluntary Service (WRVS) and the British Red Cross Society. The WRVS is government funded and received two invitations. The measure of the Home Office's wish to control the atmosphere of the conference was that it denied most of the major voluntary organisations the opportunity of responding individually to the Civil Emergencies Consultation Paper. Indeed, when they made representations to F6, they were told that they could have copies of the Discussion Paper, but would have to channel their replies through the British Red Cross Society. This proved an almost impossible task for the Field Services Organizer, who had only weeks to prepare the Red Cross's own reply.

The WRVS, a government funded agency, received two invitations to the conference. The British Red Cross Society was allowed only one, for the Chairman; the Field Services Organizer who had co-ordinated the responses of all the non-invited voluntary agencies, was not allowed to attend or represent their points of view.

Some of the excluded organisations were Raynet, who supply emergency communications; Basics, a skilled medical back-up group; Cruze, a bereavement counselling organisation, Salvation Army, Samaritans, and nine other major voluntary organisations. Many other individual experts and groups who had wide experience of international provisions for disasters were excluded.

In the ‘Review of Arrangements for Civil Emergencies’ (1989) the Home Secretary announced a small package of minor changes to emergency planning arrangements (see Chapter 2). Most welcome of these was the institution of a Civil Emergencies Training College, replacing the old Civil Defence College. As a peg within the complete restructuring of emergency planning, this was essential. Without its integration into a legally structured peacetime emergency system, it stands as a reminder that a national focus for its usefulness has yet to be defined.

The position of a Civil Emergencies Adviser was also announced, a most extraordinary concept of a post for a person who will have no power whatsoever. To have proposed such a course after two and a half years of disasters indicates how little the government is prepared to do. The then Home Secretary, Mr. Hurd, dismissed the plea from local authorities to be given a statutory duty to prepare for peacetime disasters, and omitted any personal statement of the government's possible, deep concern for those who have suffered in the continuing disasters of the past several years.

This announcement is worth contrasting with the concerns of Ministers in Charge of Emergency Planning in countries abroad. In 1986 Race Mathews, Minister for Police and Emergency Services in the State of Victoria, Australia, wrote:

‘One of my tasks is to ensure that we learn the lessons of the past and build upon them … the recovery of people and communities from the effects of any emergency needs to be planned for and managed, just as effectively as we must plan for and manage the events themselves.’

In June 1987 The Hon. Perrin Beatty, newly appointed Minister Responsible for Emergency Preparedness in Canada, expressed:

‘the federal government's desire to be ready and able to respond more appropriately to the needs of Canadians in emergency situations in an environment of increasing complexity …. We recognised the need for a … definite but flexible statutory instrument (for peacetime planning). If we do not have emergencies legislation in place, we run the risk of devising new laws under extreme pressure and tension, overlooking important considerations of fundamental rights and freedoms. Acting … in a time of calm and stability will ensure we have finely tuned legislation … that will bring Canada in line with other modern democratic nations, most of which have had similar legislation for years.’

This does not include Britain. On re-reading Mr. Hurd's statement one is struck by how much of a civil service document it is. Missing is that sense of personal responsibility and accountability which is born by Ministers who must take actual control in an emergency and bear the consequences of their actions. As such it represents the first clue to the strangely hands-off tactics which this Government has applied to civil disasters.

Paragraph 11 of Mr. Hurd's ‘Review’ (1989), states ‘the position in other countries was considered to see whether their experience could be of help’. Curiously, the only country mentioned in that paragraph is Belgium. That country – like many in Europe – operates under the Code of Napoleon, which means that in an emergency the Governor becomes virtually a dictator. While some may think this highly desirable it is hardly conceivable that the Home Office thought of this as a model.

Some of the actions which the Governor of West Flanders took during the Zeebrugge disaster were:

(i) Mobilizing the Youth Volunteer Force which had the primary role in supporting the survivors. In the spring of 1988 I proposed such a force to the Prime Minister, to the government's think tank, and finally in my response to the Civil Emergencies Discussion Paper. The Belgium Police state that they could not function properly without such voluntary backup. One notes that Prince Charles has also recently proposed the establishment of a voluntary youth force in Britain.

(ii) Closing all highways between hospitals and ports so that ambulances had free flow. This also allowed the small group of mobile operating theatres to be brought in from all over the country. The Governor is used to ordering Red Cross canteens to operate on crowded weekend motorways so that motorists have refreshments!

(iii) Sending Police to the centre of Zeebrugge to unload civilians from city buses. These were brought to the sea front in order to provide both shelter and transportation for survivors.

(iv) Commandeering hotels, even those closed due to the winter season, ordering staff to return and look after survivors, taking hotel supplies for casualties, in the knowledge that the government would compensate all commercial organisations.

In other words, full and immediate power was vested in one man. If one contrasts this with the role of the British Civil Emergencies Adviser, it is hard to believe that Belgium should have been the one country mentioned in paragraph 11 of Mr. Hurd's statement.

Disaster planning and prevention is a highly skilled professional activity. It is open to question whether a civil service approach is the right one at all or whether the Emergency Planning Unit of the Home Office should not be replaced by a skilled, on-the-ground unit seconded from experts throughout the country.

One cannot split off disaster planning into a welter of government departments whose approaches are myopic and unskilled. If the 1988 Easingwold Conference had done its job in a proper and open manner, it is doubtful that a plethora of small conferences at universities and polytechnics would be trying to fill the breach formed by a lack of public discussion. This is surely not the way to develop a pragmatic approach to disaster planning and it could be argued that it plays into the hands of a government not prepared to take control.

Academic research can contribute greatly to increasing the pool of knowledge on which workers can draw. A clear link between one central unit collating material to a disaster dispersal training unit must be established. Its work must be broken down into appropriate divisions divided into safety, prevention, response skills and recovery teams. Paragraph 15 of the Home Secretary's ‘Review’ (1989) states:

‘The basis of the response to particular disasters should remain at the local level: it is here that expertise and knowledge (my emphasis) exists, that the best information is available, and it is at this level that co-ordination between the various agencies or individuals involved can provide the most effective response.’

I would argue that the above comment might be considered to be both ill-informed and even complacent. The mass of information and first-hand accounts which have come out of every major disaster from Zeebrugge to the sinking of the Marchioness on the River Thames in August 1989, have indicated how little expertise exists in local hands. This is not intended as any criticism of those working in appalling conditions. Who has provided them with the peacetime emergency planning, the resources in funding and training and the back-up to make their response any more professional?

What is non-existent in the ‘Review’ (1989) or in anything written or stated by the Home Office is the establishment of a standard of planning and coordination by which local authorities, voluntary agencies or even counsellors can measure their response. Those working with major emergencies must have a standard of quality control by which they can measure themselves. Remember: the local fireman, ambulance driver, or social worker will normally be doing work quite different from controlling disasters.

In a report on training supplied to me by the London Ambulance Service, serious complaints on the lack of disaster training were voiced. Both the Prime Minister and the Home Office might be interested to know that videos of the Brighton bombing in October 1984 show the fire brigade evacuating Mr Norman Tebbit – not the ambulance service – with Mr. Tebbit's leg hanging off a special orthopaedic stretcher because the fire brigade did not know how to strap him correctly.

But what stands out even more clearly is our lack of concern for human beings. It is easy to talk of plans and resources, past and future. What is never said is that people are suffering and because their problems are not dealt with, that suffering will surround them and impair their functioning for the rest of their lives.

Elements of a modern emergency planning system

So: what are some of the elements which should be included in a modern emergency planning system?

(i) A statutory civil emergencies arrangement with funding from central government. This is not an expensive exercise.

(ii) A statutory requirement for regular co-ordinating meetings between police, volunteers, the central unit and union and management representatives.

(iii) An independent disaster planning unit which brings to local and regional planners the best aspects of international planning.

(iv) A Minister or Civil Emergencies Head – not adviser – who can take central responsibility in an emergency.

(v) A separate national disaster team which can bring in supplies, trained personnel and backup in a major emergency.

(vi) A safety monitoring unit which is independent of government, so that it has the power and freedom to close down anything from ferries to football stadia if proper safety procedures are not being undertaken. It is in the very nature of the commercial world to resist non profit-making expenditure. It must be made to do so in order to protect our citizens.

(vii) A rationalisation of all boundaries so that statutory and voluntary personnel understand their local, regional and national support systems.

(viii) Arrangements for registration of all trained personnel who will work in disasters, with their qualifications clearly labelled on uniforms.

This is just a brief basic list in a very short chapter. However, if I may leave you with a final thought it is this. Disaster expertise is too sophisticated a process to entrust to any but the most qualified personnel. In a disaster people should continue to do what they have been trained to do. We have a lot of work to do in Britain before this maxim can be turned into reality.

Recent developments

On 10 September 1990, eight defendants (including the captain of the Herald and the company, P&O European Ferries) were brought to trial at the Old Bailey. The charge was ‘corporate manslaughter’. Mr. Justice Turner subsequently directed the jury to acquit six defendants, with the Crown then withdrawing its case against the two remaining defendants. On Saturday, 27 October 1990, the following news item appeared in ‘The Times’ (other newspapers carrying similar stories):

The Court of Appeal is likely to be asked to give ruling on an aspect of the Zeebrugge manslaughter that could have wide implications for future legal actions arising out of disasters.

Prosecuting counsel in the trial have been asked by Sir Patrick Mayhew, the Attorney General, to study the judge's grounds for telling the jury to acquit five (sic) of those accused, to see whether his actions were justified in law. The point under examination, likely to be referred to the Court of Appeal, is whether Mr Justice Turner was right in his direction that the evidence presented at the Central Criminal Court was such that the jury should not be invited to conclude that there was an ‘obvious risk’ that the Herald of Free Enterprise would sail with her bow doors open and capsize.

Any decision by the Appeal Court would not effect the acquittal of those involved, but would clarify the law on manslaughter and go some way toward justifying the original decision to prosecute. The collapse of the case … last Friday led to calls for changes in the law whereby some form of corporate responsibility would be established.

On 12 December 1990 ‘The Times’ carried the statement that the Attorney General had decided not to refer the ruling by the judge who directed acquittals in the manslaughter trial to the Court of Appeal on a point of law.

REFERENCES

Cook, J. (1989). An Accident Waiting to Happen, Unwin Paperback, London.

Home Office (30 June 1988). Civil Emergencies – Home Office Consultation Paper. London.

Home Office (1989). Review of Arrangements for Civil Emergencies, London.

Report of Formal Investigations into the loss of the Herald of Free Enterprise (1988). HMSO, London.