CHAPTER 10

Disaster at Hillsborough Stadium: a comparative analysis

On 15 April 1989 the semi-final match of the Football Association Cup was to be played at the Hillsborough ground in Sheffield. The ground had been selected as a neutral venue to host the Liverpool and Nottingham football clubs in their competition for the opportunity to play in the final for the Cup at Wembley in London. However, the game had been underway for only six minutes when play was stopped as spectators on the terraces behind the Liverpool goal had become severely crushed. The result was that 95 people died and over 400 received hospital treatment.

Not surprisingly, the tragedy was received with shock throughout the nation, and most particularly in Liverpool where the loss of so many lives had been linked to the intense emotional feeling associated with the Liverpool Football Club. On 17 April, the government announced that an official inquiry would be established under the chairmanship of Lord Justice Taylor to inquire into the events at Sheffield Wednesday Hillsborough football ground and to make recommendations about crowd safety at sports events.

A separate inquiry was established by the police, but it is from the interim report of the Taylor inquiry (Home Office 1989) that the details about the events at Hillsborough here presented are taken. The report was presented to the Home Secretary in August 1989 and provides the full details about the nature of the disaster. The second part of the inquiry will be concerned with making final and long term recommendations about crowd control and safety at sports grounds.

In this chapter, the causes of the Hillsborough tragedy are analysed by drawing on earlier research into the organisational and administrative factors involved in the unfolding of disaster at the Heizel Stadium in Brussels, Belgium, in 1985. In particular, Perrow's theory of ‘normal accidents’ is applied to the analysis of both these disasters, drawing attention to the endemic vulnerability of mass events such as these, and the limited potential for prevention and mitigation of these disasters that is presently available among organising local authorities, and police forces (Perrow 1984).

Background: safety arrangements of the stadium

The general nature of the ground

The Taylor interim report (Home Office 1989) details the pre-match arrangements for the Cup semi-final. On 20 March 1989 the Football Association (FA) requested that the match be held at Hillsborough. This was agreed to by Sheffield Wednesday and the two teams involved in the match. In addition, the South Yorkshire Constabulary said that they were prepared to police the match provided that there were satisfactory arrangements for the issue of tickets.

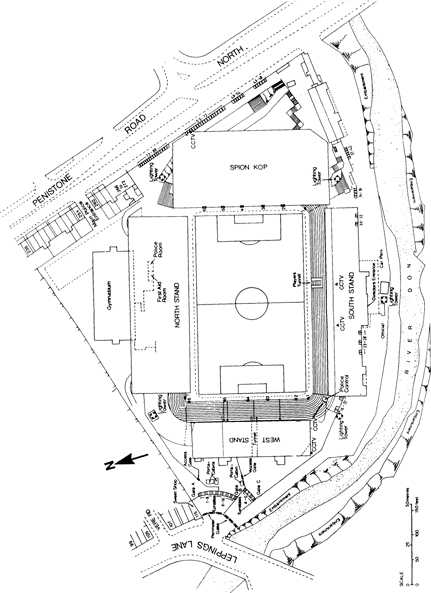

The Hillsborough stadium was regarded as acceptable by all parties, it having been the venue of many similar matches in the past. The ground lies about four kilometres from the centre of Sheffield and has been widely regarded as one of the Football League's better grounds in terms of its facilities and accessibility (Figure 10.1).

The west end of the ground is known as the Leppings Lane end, and it was here that the deaths of the Liverpool supporters took place. The east end of the ground fronts onto Penistone Road (the A61) and to the south is the river Don. To the north is Vere Road which runs between Leppings Lane and Penistone Road North. Alongside the river there is a private road which gives access to the south stand with gates which can be closed at either end. The south stand is all seating with a capacity of 8,800 people. The north stand has a capacity of around 9,700 and the east stand about 21,000 people. The east stand faces the west stand where the tragedy occurred in a ‘classic’ confrontation between ends so characteristic of British football grounds. It is in this face-to-face situation that the supporters of the opposing teams are placed for the whole duration of the match and where the designation of club ‘ends’ come from.

On 15 April, the Liverpool ‘end’ was the west stand (or Leppings Lane end). Here there is terracing close to the pitch with a covered stand behind. The covered stand has a capacity of 4,456 and the terracing has a stated capacity of 10,000 people.

Around the terracing of the Leppings Lane end, and also around the east (Kop) there is perimeter fencing about two metres high between the terracing and the pitch. At the top of the fencing the wire turns back at a sharp angle

intended to prevent climbing over onto the pitch. There are also small gates at intervals along the perimeter fencing which give access to the pitch from the terracing (Figure 10.1).

The Leppings Lane end also has the addition of crush barriers parallel with the goal line and radial fences at right angles to the ground. This divides the terraced area into ‘pens’ which, since 1981, have been used to control crushing. The pen system operates to provide a gated control mechanism for gradually relieving pressure as crushing builds up.

The turnstiles

Because of the housing in Vere Road there is no access to the ground from the north side. Along Penistone Road North there are 46 turnstiles while at the south side of the ground there are 24 (19 to 42 on the plan). The south and east sides of the ground accommodated around 29,800 spectators with access through 60 turnstiles. However, on the north and west sides of the ground there were only the 23 turnstiles at the Leppings Lane end to give access to 24,256 persons.

Travel to the ground

Most of the supporters were expected to come to the ground by road although rail transport was available. Nottingham supporters were expected at the central station in Sheffield and were to be escorted to the ground by the police. Similarly, the Liverpool supporters were expected to arrive at the mainline station by normal rail service. The rival fans were thus to be segregated at the main station. Liverpool supporters could also travel by a special train to a station to the north of the ground and used only for football trains on match days. A police escort was provided to accompany these supporters to the Leppings Lane end.

Allocation of places and tickets

Ticket allocation was based on a policy of segregation of supporters from the opposing teams, and accordingly the police decided that sections of the Hillsborough stadium should be allocated to keep the Liverpool and Nottingham sections of the crowd apart. This policy was adopted in Britain following publication of the Popplewell Report into the Bradford football stadium fire in 1985 (Home Office 1985). The sections to be allocated to each team were determined by the in-flow of fans from particular directions, so Liverpool was allocated the north and west stands and Nottingham the south and east stands.

However, this meant that Liverpool were allocated 24,256 places against the 29,000 for Nottingham Forest. This was perhaps technically the most reasonable allocation given the circumstances, but it was a controversial allocation in light of the substantially higher average home match attendances at Liverpool. Moreover, with standing tickets at £6 and seats at £12, Nottingham had 21,000 standing places compared with Liverpool's 10,100. As Taylor stated, ‘Liverpool's allocation was more expensive as well as smaller’ (Home Office 1989, para 36). The police were determined to maintain this allocation in spite of representations from Liverpool. For the police a change would have been difficult since it would have required opposing supporters to cross paths when approaching the ground and would therefore have made it much more difficult to maintain crowd segregation.

Access from Leppings Lane

The approach to the west turnstiles is across a narrow neck or forecourt at a bend in Leppings Lane (Figure 10.1). Liverpool supporters were required to approach this area on foot where they would come to a line of railings with six sets of double gates. Inside these perimeter gates is the short approach to the turnstiles. These are in two sections divided 1 to 16 Numbers 1 to 10 give access to the north stand (Figure 10.1).

Turnstiles 11 to 16 were for those with seats in the west stand which meant that 4,456 spectators were served by six turnstiles. On the other side of the dividing fence in the approach area, there were only seven turnstiles to serve 10,100 spectators with tickets for standing in the west terracing. Those seven turnstiles were labelled A to G (reflecting the old Leppings Lane numbering sequence which was not altered when changes had more recently been made to the ground). Above the lettering A to G there was a large letter B. ‘Entrance B’ also appeared on tickets for the west terrace.

Inside the Leppings Lane turnstiles

Turnstiles 1 to 10 gave access to a passage leading to the north stand. There is an exit gate (marked A on the plan). Inside turnstiles 11 to 16 is a concourse leading to pens 6 and 7 and the steps to the west stand. There is a wall dividing this area from that inside turnstiles A to G. There was, however, a gate in the wall which allowed access between the two areas. An exit has been provided from the area inside turnstiles 11 to 16.

In addition, anyone using turnstiles A to G entered a concourse bounded on the left by the wall mentioned above and on the right by the wall of the private road coming from the south stand to Leppings Lane. There was an exit gate in the latter wall (marked C in Figure 10.1) just inside turnstile G. All three gates, A, B and C, were of concertina design and could only be opened from the inside. They were not intended as entry points for spectators to the ground.

Those entering through turnstiles A to G had three options once inside the ground. They could by moving to the right go round the south end of the west stand and gain entry into pens 1 and 2. They could go through the gap in the dividing wall towards the concourse behind turnstiles 11 and 16 and then round the north end of the west stand into pens 6 and 7. However, as Lord Justice Taylor stated, the most obvious way was straight ahead of the turnstiles where a tunnel under the centre of the west stand provided access to pens 3 and 4 (Home Office 1989). Ticket holders were drawn in this direction by a large letter ‘B’ above the entrance.

Policing arrangements

The policing arrangements were under the command of Chief Superintendent Duckenfield. Under him were Sector Commanders, all Superintendents with experience of policing at football matches. Superintendent Marshall was responsible for the area outside the Leppings Lane entrance and Superintendent Greenwood was in command inside the ground. Duckenfield had command over 801 officers and men on duty at the ground plus traffic officers and others from the D Division drafted in to deal with the influx of supporters in the city centre. The total was some 1,122 police officers which was about 38 per cent of the total manpower of the South Yorkshire force. Included in the mounted section of 34 were officers from Liverpool and Nottingham.

The total number of police officers at the ground was divided into serials consisting usually of eight to ten Constables plus a Sergeant and an Inspector. The serials were posted to duties at various stations in and around the ground before, during and after the match. This was set out in an Operational Order which followed a similar Order drawn up in 1988 and took account of the forces' ‘Standing Instructions for the Policing of Football Grounds’. The Order thus described police duties for each serial and was backed by oral briefings prior to the match taking place.

Sheffield Wednesday Football Club provided 376 stewards, gatemen and turnstile operators. The stewards had been briefed to work closely with the police. The Club's control room, situated in the south stand, provided radio contact to the stewards and closed circuit television gave coverage of the situation at all turnstiles around the ground. This was combined with a computerised counting system which registered the numbers entering the ground in the central control room.

The disaster on 15 April 1989

The football match between Liverpool and Nottingham was a ‘sell-out’ so that 54,000 ticket holders were expected to arrive on the match day. Some were expected to come without tickets, possibly to purchase them outside the ground or even to try to effect illegal entry to the match.

On the match day, supporters began to arrive at the ground early in small numbers. The Taylor report indicated that some of these people had cans of beer with them and were seen drinking as they congregated near the ground (Home Office 1989). When the nearby public houses opened, many of theearly arrivals entered while others made approaches to purchase tickets from by-standers. There was also an indication that the Liverpool supporters were likely to be troublesome as some of the fans used private gardens to urinate. As the morning progressed, the number of fans increased and requests for tickets were still evident. However, as Taylor states, ‘The prevailing mood was one of carnival, good humour and expectation’ (Home Office 1989, para 54).

The gathering crowd

As the numbers of fans built up, it was evident that a crowd was forming around the Leppings Lane end of the ground. Many seemed to be reluctant to enter the ground early despite the fact that the turnstiles had been opened at 11.30. Some police officers had been deployed outside the turnstiles and in the Leppings Lane area. Some fans who did not have tickets were turned away by the police while those with tickets were encouraged to move towards the ground. Once at the turnstiles, the police checked that the fans were entering in an orderly fashion and were prepared to check for the likely possession of drink, drugs or weapons.

By 14.00 it was apparent to those inside the ground that the number of Nottingham fans in their places outnumbered those from Liverpool. At that time the turnstile figures indicated that the numbers entering the Liverpool enclosures were well down on the figures for the same time at the Cup match in the previous year.

The special train carrying Liverpool fans arrived at Wadsley Station just before 14.00. The 350 passengers were met by both mounted and foot police officers who escorted them in a ‘crocodile’ down Leppings Lane. This group of fans were orderly and entered the ground by about 14.20. Meanwhile, the numbers of supporters converging on the Leppings Lane end from other directions was increasing rapidly. It was at about this time that the area between the perimeter gates and the turnstiles ‘became congested’ (Home Office 1989, para 61). There was no longer a separate queue at each turnstile and the foot officers posted at the turnstiles found it difficult to maintain a comprehensive check on all those that were entering the ground. Mounted officers were also by this time having difficulty in manoeuvring in the dense crowd. This point is made very clear by the television coverage of the area that was indicative of a situation that was somewhat chaotic.

The television pictures also showed Superintendent Marshall on foot amongst the crowd. It is evident from the pictures, and from the Taylor report, that Marshall was anxious about the situation by the gates. As early as 14.17 he radioed to control to have motor traffic in Leppings Lane stopped. This was done at about 14.30, but there was still no perception by the police of a crisis at this time and no panic in the crowd. In the control room, Superintendent Murray was watching the Leppings Lane on video and he advised Mr Duckenfield that they would be able to get everyone in by 15.00.

Crisis at the turnstiles

It was in the period between 14.30 and 14.50 that there were crucial developments both inside and outside the ground (Home Office 1989, para 63). In pens 3 and 4 there was a steady increase in pressure as fans entered through the tunnel. By 14.50 these pens were already ‘full to a degree which caused serious discomfort to many well used to enduring pressure on terrace’ (Home Office 1989, para 63). Indeed, the numbers at that time were ‘clearly in excess of the maximum density stated by the Home Office guide to safety at Sports Grounds’. However, there was still plenty of space available in the side pens to take extra supporters.

Still the crowd grew at the Leppings Lane end, creating a crush on the front. Entry through the turnstiles became more difficult and pressure mounted on the foot officers. Feeling themselves to be in danger, the foot police entered the turnstiles and out again through gate C. The mounted officers were surrounded by the crowd with Superintendent Marshall in what was now serious turmoil. Some people panicked as the pressure mounted with some youngsters and women fainting in distress. As these people were assisted over the turnstiles, other fans began to climb up over the turnstile building to effect entry to the ground to relieve the pressure (Home Office 1989, para 64).

At 14.44, Marshall radioed for reinforcements, for the stadium's loudspeaker system to request the crowd to stop pushing and for a vehicle with loudspeaker equipment to come and request the same. However, at about 14.40, radio communication became defective and Marshall lost contact with the control room for about two or three minutes. A standby station was connected by another officer and contact was restored.

Action was taken on two of Marshall's requests. However, an announcement was made only with minimum effect, while some reinforcements were sent to his assistance. The third request, for a loudspeaker van, was eventually acted upon and the van arrived at 14.46 and urged that the crowd should not push. This request had no impact.

Mounted officers thus came outside the perimeter gates in an attempt to shut them against the crowd but pressure from outside opened the gates again (Home Office 1989, para 65). The mounted officers then formed a cordon across the elbow of Leppings Lane and this met with some success despite the efforts of some supporters to force a way under the horses. Eventually, the cordon had to give way again.

The decision to open the gates

By 14.45, the crowd inside and outside the turnstile approach had swelled to over 5,000. At the head of the crowd, conditions had become intolerable. Many in the crowd complained to the police that something should be done to relieve the pressure and exit gates A and B were being shaken. It was then that Constable Buxton radioed a request to control that the kick-off be postponed, but the request was rejected by chief commander Superintendent Duckenfield in the control room.

Superintendent Marshall then reluctantly decided to make a request that the exit gates be opened to relieve the pressure and this request was agreed with other senior officers outside the ground. The request went through to control at 14.48 for consideration by Mr Duckenfield. However, gate C was opened at this time to eject a youth who had entered without a ticket and immediately fans outside surged in through the opening. After about 150 fans had passed Marshall repeated his request twice more before Duckenfield finally gave the order to open the gates. Neither the Club control room nor any police inside the turnstiles were informed of the decision.

At 14.52, gate C was opened and later gate A was opened following the request of another police officer. Gate B was also briefly opened. The largest entry was through gate C which allowed in around 2,000 fans in five minutes at a fast walk. Some probably did not have tickets and most thus made for the terraces by way of the tunnel ahead of them with a minority going off to the left and right side pens.

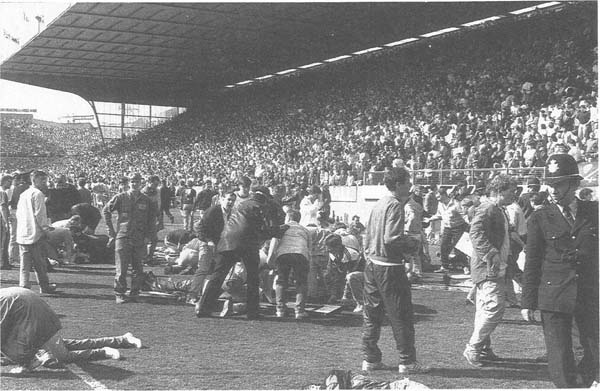

More and more fans crushed through the tunnel creating pressure at the front of the terrace. It was this crushing that led to the deaths and the pain and injury of many of the Liverpool supporters. The police did not immediately realise what was happening and in many cases fans were prevented from getting out of the area behind the closed perimeter fence. Eventually individual officers did recognise the situation and took measures to effect the release of fans from the area where the deaths where taking place (Home Office 1989, paras 71–75) (Figure 10.2). By then, the crisis had occurred and the disaster plan was put into effect.

How could it happen? The Taylor view

The Taylor Report (Home Office 1989) was very clear about where responsibility lay for the disaster and what the causes had been. In essence, Taylor placed the blame on the South Yorkshire Police for making a series of wrong decisions during the period that the disaster was taking place and prior to it. There were also important considerations relating to the safety provisions at the ground. As far as technical aspects were considered, these included the following.

The lack of fixed capacities for the pens

Taylor believes that there were a number of problems at the ground which gave rise to concern about the ground's basic safety arrangements. In his view, the provisions in the Safety Certificate ought to have been reviewed and altered

FIGURE 10.2 The crowd crush at Hillsborough football ground on 15 April 1989 in which 95 people died and over 400 were injured (Press Association)

in view of worries expressed by the police as early as 1981 that the capacity figure for the ground was too high (Home Office 1989, para 149).

The lack of effective monitoring of the terraces

Taylor pointed to the confusion about who should actually be responsible for monitoring the terraces. Should it be the police or the club or both? This was something that had also concerned the Popplewell inquiry in 1985 (Home Office 1985). In the event, Popplewell came down in favour of a situation where it was recognised that responsibility for crowd behaviour would be divided between the police and the club operating the ground. The broad line of division was that the police were responsible for the control of spectators once they were in the ground. However, the police were de facto responsible for organising the crowd even when it was in the ground and this applied throughout the game. Consequently, the club was given the role of supervising the crowd to ensure ‘good housekeeping’ and the physical safety of the ground, but the police assumed the crucial overview of crowd behaviour (Home Office 1989, para 163).

As Taylor pointed out, this was a vital point since the South Yorkshire Police ‘continued throughout the hearing to contend that the club and not the police were responsible for filling and monitoring the pens and that this was well known to both parties’ (Home Office 1989, para 168). The South Yorkshire Police maintained that the police were there essentially to ‘secure and preserve law and order’. Taylor showed that this position was inconsistent with past views expressed by the South Yorkshire Police on this matter.

In addition, Taylor pointed out that the police had enjoyed an excellent view of the Leppings Lane end from their control box. There were officers on the perimeter track of the ground but no stewards there, and there were also police in the west stand who could look down on the pens. There was thus no reason to adopt a passive role as fans were coming into the pens. Direction of fans to less crowded areas would have been possible.

Build-up at the turnstiles

Taylor recognised that the decision to open gate C and the other gates was forced on to the police by the crowd conditions (Home Office 1989, para 185). The crush was so severe that injuries were being suffered. Taylor was of the opinion that much of the problem at the turnstiles could have been avoided by better design and the provision of a more effective entry system for the Leppings Lane end. However, the police should have known in advance what pressures would have been placed on the turnstiles at that end, especially as there had been recognition of the problems there for some years. Success depended on the spectators arriving at a steady rate from an early hour and upon effective monitoring of turnstile entries.

The situation at the turnstiles thus had to be seen within this organisational context. The fact that there were some fans arriving at the entrance to the ground after having been drinking did not thus materially affect the situation. The police placed heavy emphasis on the drinking factor as a major cause of the problems at the turnstiles but the Taylor evidence showed that only a minority of the fans had been ‘the worse for drink’ (Home Office 1989, para 196).

Summary of the causes

Taylor thus summarised the causes as follows:

‘The immediate cause of the gross overcrowding and hence the disaster was the failure, when gate C was opened, to cut off access to the central pens which were overfull.

They were already overfull because no safe maximum capacities had been laid down, no attempt was made to control entry to individual pens numerically and there was no effective visual monitoring of crowd density.

When the influx from gate C entered pen 3, the layout of the barriers there afforded less protection than it should and a barrier collapsed. Again, the lack of vigilant monitoring caused a sluggish reaction and response when the crush occurred. The small size and number of gates to the track retarded rescue efforts. So, in the initial stages, did lack of leadership.

The need to open gate C was due to dangerous congestion at the turnstiles, that occurred because, as both Club and Police should have realised, the turnstile area could not easily cope with the large numbers demanded of it unless they arrived steadily over a lengthy period. The Operational Order and police tactics on the day failed to provide for controlling a concentrated arrival of large numbers should that occur in a short period. That it might so occur was foreseeable, and it did. The presence of an unruly minority who had drunk too much aggravated the problem. So did the Club's confused and inadequate signs and ticketing’ (Home Office 1989, paras 265–268).

Toward explaining the Hillsborough disaster: a comparative analysis

‘Norma’ accidents

According to the organisational sociologist Charles Perrow, there are endemic problems in the design and day-to-day operation of many socio-technical systems, such as advanced industrial production plants and modern transportation systems. In many petrochemical plants, aircraft industries, and other high-tech projects errors and disturbances are not only inevitable; much worse, in these settings they tend to compound and escalate in such a manner as to become unmanageable. In that sense, the resulting calamities are ‘normal’ (i.e. more or less endemic).

He characterizes his theory as follows:

‘Perhaps the most original aspect of the analysis is that it focuses on the properties of systems themselves, rather than on the errors that owners, designers and operators make in using them. Conventional explanations for accidents use notions such as operator error; faulty design or equipment; lack of attention to safety features; lack of operating experience; inadequately trained personnel; failure to use the most advanced technology; systems that are too big, underfinanced, or poorly run (…) But something more basic and important contributes to the failure of systems. The conventional explanations only speak of problems that are more or less inevitable, widespread and common to all systems, and thus do not account for variations in the failure rate of different kinds of systems. What is needed is an explanation based on systems characteristics.’ (Perrow 1984, p. 63.)

Taking his analysis to the systems level, Perrow distinguishes between two crucial system properties: interactive complexity and tight coupling.

Interactive complexity refers to the complex and unthought-of interdependencies that exist between different components of the system. This gives rise to situations in which when components A and B fail, this unexpectedly leads to other failure and events which, in turn, trigger yet other surprising problems. For instance, who would have thought that, in factory X, the running over of the water tank from the cooling system would trigger a devastating short-circuiting and subsequently a fire? This could occur because the spoiling water affected could reach the central generator which was just a number of metres away from the tank, and whose water resistant door was accidentally left open by maintenance personnel. Two disturbances/errors interact in an unforeseen way: the failing water tank and the opened door of the generator.

The tight coupling between different components of these systems compounds the problem. As Perrow notes, ‘… suppose the system is also “tightly coupled”, that is, processes happen very fast and can't be turned off, the failed parts cannot be isolated from other part, or there is no other way to keep the production going safely. Then recovery from the initial disturbance is not possible; it will spread quickly and irretrievably for at least some time.’ (Perrow 1984, pp 4–5).

Perrow uses the complexity coupling distinction to devise a tentative typology of different systems vulnerability to normal accidents (see Figure 10.3). Perrow does not contend that all or even a very large number of disaster are caused by normal accidents. However, he does suggest that certain socio-technical systems are particularly conducive to the fatal combination of interactive complexity and tight coupling. In these systems, even seemingly insignificant irregularities or small errors may trigger chains of disruption and, ultimately, destruction, that can hardly be stopped.

The top right-hand corner of Figure 10.3 contains activities which are most prone to normal accidents: NAP systems. These are all very much technology-driven processes – typical man-made disasters in the original sense (Turner 1978).

Extending normal accident theory

In their study on the 1985 Heizel football stadium tragedy, 't Hart and Pijnenburg (1988) argue that ‘high-tech’ settings are not unique in their vulnerability to normal accidents. In effect, the most dominantly ‘social’ setting of mass gatherings provides for an entirely different class of events that, potentially, have properties that make them susceptible to the dynamics of normal accidents. These include sports matches, large-scale rock concerts, leisure centres, and the more comprehensive kinds of shopping malls.

The interactive complexity of these ‘systems’ derives mainly from the fact that in each of these activities very large numbers of people are gathered in a relatively limited space. They of course differ in the degree of complexity, depending upon additional factors: the dependency upon infra-structural or technical facilities in the regulation of the event or the activities; the homogeneity/heterogeneity of the crowd; and the degree of conflict existing between various groups within the broader gathering. Despite such variations, most of these events should be ranked as interactively complex. Consequently, they present ‘operators’ and ‘controllers’ with problems of surprising interactions similar to those encountered in ‘high-tech’ environment. To a considerable extent, this is caused by the limited knowledge about crowd behaviour in different situations available to both the planners of these activities (designers, managers, police commanders) and on-the-spot operators such as police officers, stewards, and security personnel. Put simply, these officials do not know much about how to regulate masses of people, especially in extraordinary conditions of different kinds. To be sure, knowledge and practical action guidelines are being developed in specialised circles, but their penetration into practitioners' circuits is limited. Many of them rely solely on personal experience and organisational routines in planning and monitoring mass events.

Tight coupling in mass events derives mainly from inherent as well as unforeseen limitations of time and space. The physical infrastructure of a concert hall, an indoor leisure centre or a sports stadium constrains the

movements of their users. When facilities such as these are filled to capacity or even become overcrowded, the usual slack or redundancy diminishes. This occurs, for instance, by greatly increasing the number of people having to use certain ire exits in a limited period of time available for safe escape in an emergency. Time factors alone can intensify tight coupling, for example when mass transportation capabilities are not matched adequately to the timing of the activities or programmes that form the very reason for the gathering.

The normal accident interpretation of mass disasters does not neglect the role of human factor components. In an almost purely social system, it is not realistic to reduce the causes of major accidents to technological flaws (or flaws in handling technology) only. Rather, one should look for the personal, organisational and inter-organisational dynamics shaping the planning, preparations and interventions that affect the operation of these systems. The NAP-framework adds to this by providing a more fundamental explanation of the occurrence, interactions and consequences of specific errors that contribute to mass disasters.

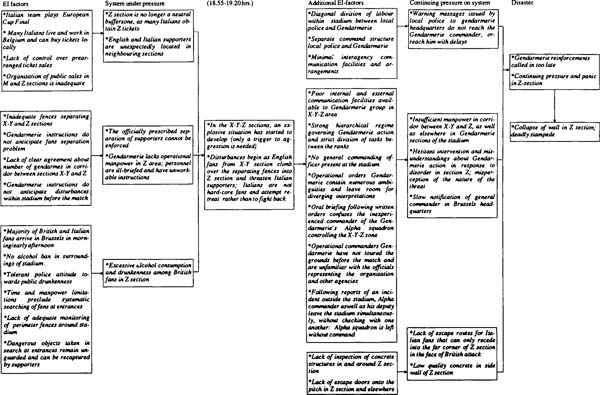

Normal accidents in Brussels

On Wednesday 29 May, 1985, the European Soccer Final was scheduled to be played at the Heizel stadium in Brussels, Belgium ('t Hart and Pijnenburg 1988, 1989). The teams involved were Liverpool Football Club and Juventus from Italy. One hour before the kick-off serious riots broke out in the Z section of the stadium, as Liverpool fans from the X-Y sections stormed the Z section containing Juventus supporters (see Figure 10.4). The Z section was planned to be a neutral buffer zone filled with Belgian spectators, but this turned out not to be the case. The Italians had obtained tickets for the Z section through various channels; many Italians work in Belgium and could have obtained tickets locally.

The Italian supporters attempted to escape the attack but could not do so as they were at the side of the stadium and the few exits onto the field remained closed by the Belgian Gendarmerie who continued to fear for an invasion of the pitch.

Eventually, the side wall to the Z section gave way and collapsed under the immense pressure of bodies. This sudden relief of pressure in the crowd created a stampede of people again attempting to escape, killing 39 mostly Italian spectators and causing injury to about 450 supporters.

How could this accident happen? As is often the case with major disasters and as already suggested by Taylor's summary of causes (Home Office 1989), no single factor was responsible for the tragedy. It was caused by the accumulation and interaction of flaws and errors in the planning and staging of the match, and the way in which these affected crowd safety and public order maintenance on the day itself. At that particular time and place, this set of (often very minor and perfectly understandable) shortcuts, routines and errors produced a fatal chain of events – conforming quite closely to the normal accident interpretation.

The sum of preparatory initiatives and organising activities with regard to the match of 29 May 1985, can be viewed as, in Perrow's terminology, an ‘error-inducing’ system. Consequently, the resulting ad hoc structure and setting of the Heizel soccer match contained built-in weaknesses conducive to disaster. These separate EI-factors and their resulting interaction are described in greater detail in Figure 10.5.

Beginning with the left side of Figure 10.5, several critical mishaps can be identified in the intra-organisational and/or collective preparations of the Belgian Football Association, the city of Brussels, Brussels police, Belgian Gendarmerie (Brussels district), the two contending clubs, the Belgian Ministry of the Interior, juridical authorities and the emergency services. These include the following:

Complex, ambiguous, and occasionally even contradictory sets of rules governing the preparation of the match with regard to crowd safety (UEFA, Ministry of Interior, Belgian Football Association, and Gendarmerie had all issued guidelines governing the preparation of major matches), with the net result that participants from various services paid little if any attention to formal requirements and relied on habits and ‘common sense’;

The highly informal mode of conducting the inter-agency coordination meetings: no minutes were taken of the proceedings, emergency services were excluded from participation, and there was a lack of administrative

leadership in reconciling bureaucratic stalemates between local police and Gendarmerie that resulted in an odd diagonal division of labour between the public order services operating within the stadium (half of the stadium would be policed by the Gendarmerie, and the other half by local police, each with their own, independent command and communication systems);

Non-decisions or negative decisions about key issues involving crowd safety, such as the lack of attention to the quality of the stadium's infrastructure, the banning of alcohol in and around the stadium, and transportation of supporters to and from the stadium;

Flaws in the allocation of tickets by the Belgian FA, as a consequence of which the official objective of continually separating rival fans was not met;

Misperception of the risks and insufficient organisational attention paid to issues of preparation, instruction, on-site inspection, command, and communication on the part of the Gendarmerie, which at the time was preoccupied with the forthcoming papal visit to Brussels.

The middle section of Figure 10.5 describes the way in which clusters of El-factors allowed a dangerous situation to develop in the X-Y-Z section (Figure 10.4). This in itself might not have been fatal, had the system retained its self-corrective capacity (in this case: had the notification and intervention of public order agencies notably the Gendarmerie been appropriately prepared and timely implemented). Yet this was not the case. The final set of buffers in the way of the unfolding disaster did not operate as envisaged. This happened because other clusters of El-factors (pertaining to the internal organisation and operations of the Gendarmerie, as well as to police-Gendarmerie coordination and communication arrangements) adversely affected intervention capabilities.

In the critical 25 minutes until 19.30, the system's interactive complexity and tight coupling came to the fore. Consider the following key events and their chain-wise interaction:

–To their complete surprise the Gendarmerie discovered, when it was too late to prevent or alter the situation, that Liverpool and Juventus supporters were standing in neighbouring sections, and that unrest was starting to develop.

–Only a limited number of gendarmes occupied the corridor between the X-Y and the Z sections. This was the result of the vague and ambiguous agreement made during preparatory meetings. The Belgian FA thought to have been assured that an entire cordon of Gendarmes would occupy the corridor, while the Gendarmerie afterwards maintained that no such request had ever been communicated by the FA.

–The members of the Alpha squadron facing the turmoil did not know how to respond to it, as they were not adequately trained and had orders which completely focused on preventing an invasion of the pitch by the supporters as the overriding concern – as a consequence, when Italian fans sought to escape the deadly crush in section Z by climbing over the fences onto the pitch, they were initially forced back in by the Gendarmes standing there.

–At this critical juncture, a gap in the operational command structure occurred: the Alpha squadron's commander and his deputy had both left the stadium responding independently to a call about a robbery outside the arena. Gendarmerie's written and unwritten rules strongly forbade lower-level personnel to surpass their direct superiors in calling for assistance. As a consequence, the platoon commander at the Z section spent some agonizing minutes deliberating whether or not to take such an initiative. When he finally acted, his call for reinforcements could hardly get through because of faulty radio equipment (worn-out batteries). Other communication problems crippled the warning efforts of other officials that might have resulted in timely deployment of reinforcements forcing back the Liverpool supporters. Failed warning attempts were made by FA officials even before 19.00; similarly, the Gendarmerie's supreme commander who was visiting the match as a guest, had the greatest difficulty in reaching the general commander who had decided to conduct the operation from Brussels headquarters.

Hillsborough: a normal accident?

In many respects, the Hillsborough disaster was a unique event involving an extraordinary combination of causative factors. However, from an analytical perspective, the combination of techno-structural and socio-organisational causes of the disaster seems remarkably similar to those that played a role in other major disasters, such as the one in Brussels. Let us confront the evidence and examine the similarities and differences between the Brussels 1985 and Sheffield 1989 disasters.

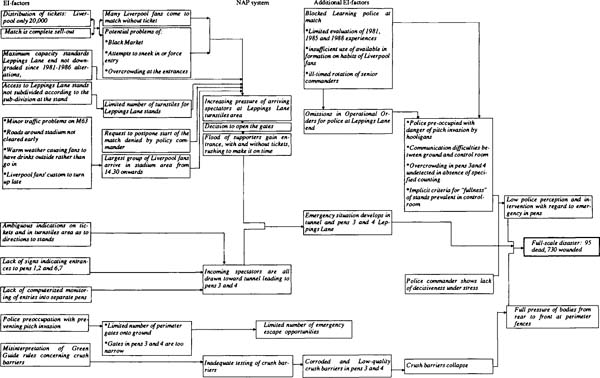

Taking the NAP-perspective as a guideline for a deeper analysis of the Taylor conclusions (Home Office 1989), the dimensions of interactive complexity and tight coupling stand out (Figure 10.6). First of all, several features of the set-up and preparations for the match contributed to complexity:

–The set up of the entrances and corridors to the Leppings Lane end (lack of signposts indicating south entrances to pens 1 and 2 (Figure 10.1);

–The ambiguous and uncoordinated indications for directions of Leppings Lane end ticket holders on the tickets themselves and in the turnstiles area;

–Omissions in the operational orders and the division of responsibilities contributing to a lack of understanding of the interrelationships between conditions at the entrances and inside the pens on the part of senior police officers;

–Misinterpretations and/or violations of Green Guide safety regulations,

resulting in insufficient testing of crush barriers in pens 3 and 4 and making them vulnerable under pressure (Figure 10.1).

These different clusters of EI-factors started to interact on the afternoon of the match. Few if any of the officials and police officers on duty that day foresaw the fatal chain of events: mass arrival of Liverpool fans with and without tickets, a large majority floating into the tunnel leading to pens 3 and 4 while other areas remain almost empty, followed by a decision to open gates which reinforced this flow. This was not communicated to police inside the stadium. Pressure in pens 3 and 4 mounted, crush barriers gave way putting the full pressure on the front perimeter fences of pens 3 and 4. Police officers misperceived the cause of the crush. The police commander did not grasp the enveloping emergency from watching the monitors. Even when the emergency became apparent the number of perimeter gates onto the pitch was limited, hence the quick release of pressure was impossible. Disaster ensued.

As evident from this flow of events, the system had become more tightly coupled by a number of additional EI-factors:

–The distribution of tickets to both teams, leaving many Liverpool fans without tickets, with the result that many non-ticket holders showed up at the entrances, increasing the number of people present;

–The combination of pleasant weather, Liverpool fans' habits in turning up late in the stadium itself, and some minor traffic delays due to roadworks – together these factors caused a large number of supporters holding tickets for the Leppings Lane end to converge near the entrances at a relatively late moment (from 14.30 onwards);

–The limited number of turnstiles available to effect entry at the Leppings Lane end;

–The disinclination on the part of the police commander to postpone the start of the match and hence continuing the time pressure (failed attempt to decouple the system);

–The final act of opening the gates, which can be compared to eliminating a safety valve in a high-pressure system: the original buffer zone to control the flow of incoming fans was gone.

Conclusions

In the conclusion of his book, Perrow (1984) suggests that society needs to rethink its widespread use of certain high-risk technologies prone to normal accidents, such as nuclear power. Abandoning nuclear power stations is the sole effective means of preventing (civilian) nuclear disasters, Perrow argues, because it is virtually impossible to effectively intervene in their tightly coupled and interactively complex operations, once a major disturbance has become apparent. Once set in motion, a more or less ‘inevitable’ chain of events can lead to disaster.

Some observers may disagree with this assessment. It may, nevertheless, be worthwhile to transplant Perrow's assessment to the context of mass leisure events, in particular large-scale football matches. Unless radical measures are taken to simplify and de-couple these ‘systems’, disasters of the Heizel and Hillsborough types are bound to occur from time to time. And that is a high price to pay for entertainment.

Examining the two disasters, the similarities in some of the error-inducing factors in preparation and decision making are striking:

–problems with distribution of tickets creating the roots of the problems;

–infrastructure shortcomings detracting from the stadium's safety;

–violation (more through negligence than as a conscious choice) of safety rules and regulations;

–police forces operating on the basis of ‘common sense’ rather than thorough vigilance;

–ambiguities in inter-organisational planning with regard to the division of responsibilities for safety and crowd control;

–key breakdowns of communications, decisiveness and lower- level initiatives under conditions of stress.

This list of similarities could be greatly extended if we include the crisis and post-crisis response of the various agencies concerned: the cumbersome relations between emergency services and security forces, widespread buckpassing and blaming, misinformation during debriefings.

To be sure, the two disasters were all but identical. The Heizel Stadium disaster was triggered by more or less 'classical’ hooligan confrontations between rival groups of supporters. The bitter irony of Brussels was that only the Liverpool fans were hooligans; had the Italians in Z been hard-core fans rather than assorted supporters and families, things might have turned out differently. Fan violence did not play any significant role at Hillsborough. What can be said, however, is that these disasters were two out of a much larger number of disaster scenarios that can be drawn up in the context of large-scale football matches and other mass events (Rosenthal and 't Hart 1990, Pijnenburg and Van Duin 1991).

The very complexity of these events makes for this variation, and poses debilitating problems for those officials and agencies involved in maintaining safety and security. Taking measures to prevent fan confrontations in the stadiums displaces problems to the stadiums' surroundings, or negatively affects safety provisions in case of other emergencies (for example: erecting thick fences and limiting perimeter gates). At the same time, measures to enhance safety and escape possibilities in case of emergency may unwittingly facilitate disturbances at matches (removing perimeter fences enables fans to storm the ground, as happened in the weeks following the Hillsborough disaster).

The diagnosis of this chapter suggests that more fundamental measures are necessary to limit the risks. While crowds of over twenty or thirty thousand people will provide inherently ‘complex’ situations in the sense of unpredictability, it is possible to break through tight coupling. This may be achieved by reducing attendance at football matches, rethinking infrastructure facilities, further enhancing crowd monitoring facilities, and strengthening supervision of compliance with safety regulations. Also, emergency services need a more prominent position in the inter-organisational planning of major matches to obtain a clearer view of what is needed to optimise safety. Finally, although prevention is better than cure, the intervention capabilities of security forces need to be improved, and learning from past experiences should become more institutionalised.

Many of these proposed measures are pursued by way of incremental improvements in various stadiums or police forces. Nationally and internationally, however, the political discussion seems to have become focused on the policy of registering all spectators at football matches by requiring them to carry an identity card. This would facilitate repressive action against hooligans, and would, ultimately, become an effective deterrent against fan violence. The discussion and analysis of the present article suggests that this is too narrow a focus, apart from being controversial with the public and interested parties. In our view, identity card schemes are, at best, only part of the effort needed to make football matches more safe, as there exists a wide range of other potential disaster scenarios at football matches and other mass leisure events. Only more comprehensive policy initiatives can hope to try and reduce (but never eliminate) the number of ‘normal accidents’.

REFERENCES

Home Office (1985). Committee of Inquiry into Crowd Safety and Control at Sports Ground – Interim Report by Lord Justice Popplewell (Cmnd. 9585), HMSO, London.

Home Office (1989). The Hillsborough Stadium Disaster, 15 April 1989. Inquiry by the Rt Hon Lord Justice Taylor (Cmnd 765), HMSO, London.

Perrow, C. (1984). Normal Accidents: Living with High-Risk Technologies, New York, Basic Books.

Pijnenburg, B. and Van Duin, M.J. (1991). The Herald of Free Enterprise disaster: elements of a communication and information scenario, in: U. Rosenthal and B. Pijnenburg (eds) Crisis Management and Decision-Making Simulation Oriented Scenarios, 45–73, London, Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Rosenthal, U., and 't Hart, P. (1990). Riots without killings: policy learning in Amsterdam, 1980–85, in: U. Rosenthal and B. Pijnenburg (eds) Crisis Management and Decision-Making Simulation Oriented Scenarios, London, Kluwer Academic Publishers.

't Hart, P. and Pijnenburg, B. (1988). Het Heizeldrama: Rampzalig Organiseren en Kritieke Beslissingen, Alphen, Samsom (in Dutch).

't Hart, P. and Pijnenburg, B. (1989). The Heizel Stadium Tragedy, in: U. Rosenthal, M.T. Charles and P. 't Hart (eds.), Coping With Crises: The management of disasters, riots and terrorism, Springfield, Charles Thomas.

Turner, B.A. (1978). Man-Made Disasters, London, Wykeham.

SECTION SUMMARY III:

Issues in explaining responses

The contributions in this section provide further evidence of the condition of hazard management and emergency planning and management in Britain. They focus on the prevailing structures and attitudes within the public and private sectors. In doing so they provide some insight into the factors underlying the British response to disaster.

Barrett and Howells point out that ‘Recognition of the need for emergency planning against industrial accidents took a surprisingly long time to develop in the UK’.

Regulation

British law tends to be reactive rather than proactive: it prefers to allocate blame and damages or penalties after loss has been sustained rather than attempt to prevent the damage in the first place. In contrast to other European legal systems there is no general offence for endangering life. The various health and safety regulations attempt to fill this gap by prescribing standards. This raises the issues of the adequacy of the regulations and the adequacy of enforcement.

In Britain, as elsewhere, all too often standards are examined and upgraded only after the most painful process consisting of a disaster, an inquiry, and political pressure for the implementation of the inquiry's recommendations; when, as Barrett and Howells observe, the response is often to legislate piecemeal. In some cases additional technical investigations may be carried out. Frequently the hazards have been well established for decades; in the case of ro-ro ferries since 1854. In such cases further investigations may be simply a waste of money and a way of putting off necessary change.

The best and most comprehensive regulations are of little use in the absence of effective enforcements. In the UK enforcement responsibilities are fragmented. Also the UK system has perhaps long been undermined by the use in legislation of the phrase ‘so far as is reasonably practicable’ instead of performance standards. Many of the contributors to this volume have highlighted areas where existing safety regulations have been violated with apparent impunity. In Chapter 8 Spooner observes that those working on ships are not covered by the Health and Safety at Work Act. He also shows that before the Zeebrugge tragedy while it was an offence to have a vessel in port in an unseaworthy condition, it was not an offence to put to sea in an unseaworthy condition: an example of the many strange gaps in legal coverage. The Cullen inquiry into the Piper Alpha explosion has found that safety at offshore oil installations was seriously deficient. It recommended that the system of companies effectively policing themselves be changed to one where the Health and Safety Executive has the responsibility.

Trends in corporate and public management

In the context of this volume we are concerned with safety-related attitudes within organisations, and with more general trends in corporate and public management.

Mrs. Thatcher's enterprise economy has unashamedly put financial performance as its first goal for both the public and private sectors. At one level this preoccupation, a ‘culture of profit’, has meant that financial performance has been at the expense of safety-related areas. This is certainly an attractive scapegoat. It is undoubtedly at least partly the case. However, a different view was put by Mr. Justice Sheen (reported by Spooner), when he observed that ‘From top to bottom the body corporate [the ferry company] was infected with the disease of sloppiness’. Jacobs and 't Hart document poor management practices as part of the cause of the Hillsborough disaster.

Trends in public administration are explored by Hood and Jackson. They identify a number of trends common to a greater or lesser degree between the English-speaking industrialised countries. These include: break up of administrative units, corporatised and privatised units dealing with each other on a user-pays basis; an emphasis on cost-cutting; an emphasis on output targets rather than process controls; and deregulation with greater accommodation of business. Across these trends are others such as the politisation of the public sector and a preference for hiring executives on short term contracts. They argue that there is evidence that these trends are part of a ‘recipe of disaster’. It is this concern that has motivated the corporate responsibility project mentioned by Spooner.

Both Hood and Jackson and Jacobs and 't Hart draw on Perrow's (1984) typology of organisations, further developed by Wildavsky (1985). Tightly coupled complex organisations are seen as particularly susceptible to disaster. Recovery from error is difficult to achieve, and malfunctions are immediately transferred from any part of the system to other parts. These typify the organisations controlling modern technology, and Jacobs and 't Hart suggest that they may also apply to mass leisure events such as football matches. They suggest that positive measures are required to ‘de-couple’ such systems otherwise disasters are bound to recur.

One interesting result of the spate of British incidents, and a possible reaction to a perceived weakness in safety regulations and enforcement linked to the strong forces maintaining the status quo (e.g. shipping companies), has been the emergence of associations representing victims and the families of victims. The emergence and persistence of such groups is a sure sign of serious flaws in hazard and disaster management. Spooner discusses the activity of the group established following the Herald of Free Enterprise disaster. This association has focused on the issue of corporate responsibility, and has seen executives of the ferry company charged with corporate manslaughter. Similar groups represent those associated with the King's Cross fire, the 1988 Clapham rail crash, the Lockerbie air disaster, the Piper Alpha explosion and the Hillsborough disaster. They have not received encouragement from government, the corporations involved or from social workers.

Concluding comment

The development of a coherent national strategy for dealing with disasters appears to be hampered by the absence of any overall philosophy for hazard reduction, except possibly for the ‘so far as is reasonably practicable’ approach. However, this approach may be part of the problem, and may underlie the piecemeal approach to reform. The fragmentation of enforcement responsibilities and the independence of the various parts of the public service from each other also work against the development of a unified approach. In a political climate of strong deregulation, hope may lie with a strengthened sense of corporate responsibility.

REFERENCES

Perrow, C. (1984). Normal accidents. New York: Basic Books.

Wildavsky, A. (1985). ‘Trial without Error: Anticipation vs. Resilience as Strategies for Risk Reduction’, CIS Occasional Paper 13, Centre for Independent Studies, Sydney.