CHAPTER 3

Peacetime emergency planning in Britain – a County Emergency Planning Officers' Society view

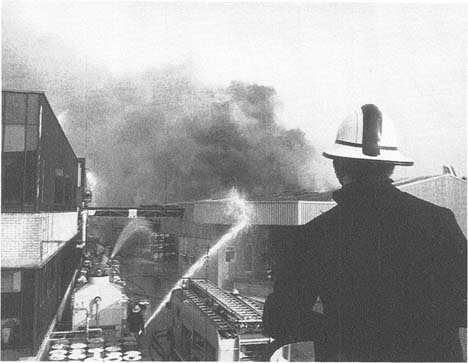

The British drug houses fire, Poole, Dorset, June 1988

The night of 21 June is the shortest night of the year but in 1988 it proved to be anything but short to the emergency services, voluntary agencies, local authority officers and residents of the Borough of Poole in Dorset. This was the night of the British Drug Houses (BDH) fire when over 3,500 people in Old Poole were evacuated and accommodated in three separate rest centres. As I understand it, this was the then largest evacuation of civilians in Britain since the Second World War. Fortunately, no-one was killed or seriously injured.

Shortly after 18.30 hours fire ripped through a storage warehouse at the BDH chemical works in the heart of Poole Old Town (Figure 3.1). A series of explosions followed the outbreak of fire, shattering windows and hurling 45-gallon drums hundreds of feet into the air. Miraculously there were no direct casualties from the blast although a few people were treated for smoke inhalation at nearby Poole General Hospital.

Over one hundred firemen tackled the blaze with eighteen appliances while dozens of police cordoned off the area and evacuated over 3,500 people from the houses and tower blocks that surround the factory. The Women's Royal Voluntary Service were assembled quickly by their local Emergency Services Organiser, who happened to be on Poole Quay only a few hundred metres from the incident. The British Red Cross Society and St. John Ambulance Brigade swung into action to provide care and assistance at the three rest centres that were hurriedly opened to accommodate the evacuees.

Although not designated in the County's Emergency Co-ordination Plan,the Poole Arts Centre was pressed into service by the police and became the main

rest centre. A performance at the Centre continued in the best traditions of show business and later the actors gave two further performances for the, by then, weary ‘evacuees’. Behind the scenes, Poole's Town Clerk and Chief Executive Officer, assembled his Emergency Management Team. On-site meetings were held with the emergency services and a policy was formulated for the care of the homeless. When 3,500 people accompanied by numerous cats, dogs and caged birds leave their homes at short notice a great deal of organisation is required. There was the registration of who had gone where, hampered by the fact that many people decided that self-evacuation to Aunt Hilda was the order of the day! How many people actually live in Langland Street? Where should the warning notices be sited? Where can we get baby food and toiletries at 22.30 hours? Could the Royal Marines supply mattresses from their nearby base at Hamworthy?

Local buses were used to augment the many ambulances that were required to transport the frail and elderly to the rest centres, and were later used to return them to their homes at 05.00 hours the following morning. Children on an exchange trip from Sussex were caught up in the evacuation and were taken with their teachers to a local secondary school for the night. Although Poole's Emergency Management Team knew that they had been evacuated safely, in the confusion it was not clear where they had actually gone. It was some time before anxious parents in Peacehaven could be assured that all seventy-four children were accounted for.

As so often happens on occasions such as these ‘Lady Luck’ played her part. The weather was warm and dry and the light breezes carried the worst of the irritant smoke and fumes out to the sea. Indeed four anglers, four kilometres offshore, were showered with debris. Had the wind been the more normal south-westerly the numbers evacuated could have run into tens of thousands and if it had been raining conditions in the rest centres would have been far less comfortable.

I was alerted by the police, contacted my staff and went to the police headquarters to act as a link between the Borough and the County should County resources be required. The Area Emergency Planning Officer for Poole Borough was on his way to give a civil protection presentation to an adjoining Parish Council when he heard the news on his car radio from the local radio station. He left his bemused audience to the delights of the video entitled 'should Disaster Strike’ and hurried off to the designated rest centre at one of Poole's secondary schools. The Bournemouth and Christchurch Area Emergency Planning Officer reported to Poole's Chief Executive and acted as his staff officer throughout the night (County Emergency Planning Officer 1988).

From this fire, which was classed as a Major Incident, the Dorset County Emergency Planning team drew eight lessons:

(i) County Emergency Co-ordination Plan

It is essential to outline terms of reference and responsibilities of each individual agency in the plan and how they co-ordinate and co-operate during an incident. The County Emergency Co-ordination Plan was published in Dorset in 1985 but there is no legal requirement or duty to prepare such a plan and there is no national uniformity or guidance for the production of such documents.

(ii) Committee for disaster planning

There is a vital need for emergency services, health authorities, voluntary agencies, local authorities and emergency planners to meet regularly to establish liaison, understand individual problems and take measures to improve co-operation, not only at an incident but at the planning, training and exercising stages. This committee meets twice a year in Dorset chaired by the Chief Executive but is normally run by the County Emergency Planning Officer (CEPO). There is no statutory duty for any agency to attend but normally all participate.

(iii) Command and Control

This must be clear cut, effective and unambiguous. In the case of the BDH fire the Chief Fire Officer led on-site; the police co-ordinated off-site operations and chaired the majority of on-site meetings; the Chief Executive of Poole Borough Council chaired his Emergency Management Team and provided support to the emergency services operations especially measures dealing with the public. There is a national need for guidance on best practice for the involvement of local authorities.

(iv) Good co-operation and the flexible use of plans

Good co-operation and liaison was evident between all agencies and the Dorset County Council Emergency Co-ordination Plan was used flexibly. Rigid adherence to all details of the plan was not followed, indeed each incident will provide new and perhaps unexpected challenges. A standard framework for a Plan for all Counties may be forthcoming from the CEPO's Society shortly.

(v) Expand list of potential rest centres

Lists of nominated rest centres in local authority Plans need to be expanded to include commercial sites not directly under local authority control.

(vi) Management of rest centres

Registration was complex in the ‘free flow’ of evacuees at the Poole Arts Centre. Consideration must also be given to the arrival of large numbers of pets, medication for elderly persons, identification of rest centre personnel and provision of a public address system. Standardisation of registration nationally could be beneficial.

(vii) Off-site plans for non-CIMAH sites with potential public hazard

Local authorities should draft guidance on off-site implications for all potentially hazardous sites, even if they are not included in the statutory requirements of CIMAH (The Control of Industrial Major Accident Hazards) regulations of 1984. Extension of provisions of CIMAH regulations to many more potentially hazardous sites needs to be considered.

(viii) Communications

No debrief would be complete without reference to communications. This must include management communication established by regular on-site round-table discussions, headquarters radio communications and information to the media and the general public.

Operations in Dorset on the night of 21 June 1988 went relatively smoothly mainly due to the professionalism of the emergency services, the goodwill existing between all agencies, the flexible adherence to a basic plan and the previous establishment of an understanding between agencies at regular meetings of the Dorset Committee for Disaster Planning.

Critique of current arrangements for peacetime emergency planning

At present there is no statutory requirement for local authorities to produce a Peacetime Emergency Co-ordination Plan. There is no duty imposed on emergency services, voluntary agencies and local authorities to meet regularly and establish the ‘rapport’ so essential to the smooth and expeditious execution of emergency plans. However, there is clearly a moral responsibility to do so as a ‘duty’ to the population that the agencies and services serve. Many County and District Councils develop contingency plans but this practice is by no means uniform throughout England and Wales. The Civil Protection in Peacetime Act 1986 allows local authorities to use resources supplied for Civil Defence (wartime) purposes to meet the effects of peacetime disasters. This means that emergency centres, communications and personnel may be used during a peacetime incident but it gives no clearance for their use during the planning stage or during training and exercising.

Several Counties now employ Peacetime Officers for Emergency Planning especially to implement the requirements of the 1984 CIMAH regulations which require local authorities to develop plans, in conjunction with the Site Operators and Emergency Services, for any off-site consequences of storage/ processing facilities involving appropriate quantities of specified hazardous substances. This off-site plan must provide information to the public living nearby. In some Counties officers draft appropriate Oil Pollution Contingency Plans where the CEPO is the County Oil Pollution Control Officer. These officers are funded directly by the County Council while the rest of the emergency planning staff are funded via 100% central government grant aid -for war planning only.

The Home Office ‘Review’

The CEPO Society welcomes the Home Office (1989) ‘Review of Arrangements for Dealing with Civil Emergencies in the UK’, especially the appointment of a Civil Emergencies Adviser and the enhanced role for the Emergency Planning College. The Society in particular noted the following in its Press Release after the announcement in the House of Commons by the Home Secretary (County Emergency Planning Officers' Society 1989).

(i) That the Review has acknowledged existing gaps in local arrangements and provides positive action to rectify them.

(ii) While the Society would have preferred to see new statutory duties placed on local authorities, the appointment of a Civil Emergencies Adviser is a timely step, and we look forward to working closely with him and his staff.

(iii) The decision to give the Civil Defence College a peacetime emergencies role and to re-name it the Emergency Planning College is most welcome, and will enable the existing close relationship between the County Emergency Planning Officers and the College to enhance peacetime emergency planning.

(iv) The decision to utilise existing agencies will allow the expertise of County Emergency Planning Officers, in providing co-ordination planning in support of the emergency services, to be developed further.

Although the Review (Home Office 1989) specifies that one of the Civil Emergencies Adviser's particular concerns will be ‘the development and dissemination of good practice and information, in particular about local coordination’, the Society feels that this will inevitably lead to the requirement of a statutory duty and little real progress will be made until this is enacted.

‘The Times’ in August 1989 has been the vehicle for a sustained bombardment of letters to the Editor on unanswered needs of civil disaster preparedness and I can do no better than reproduce in full the joint response from the Civil Protection Co-ordination Group and subsequent contributions. This Group incorporates the County Emergency Planning Officers' Society, the Association of Civil Defence and Emergency Planning Officers, the Institute of Civil Defence, the National Council for Civil Protection and the Society of Industrial Emergency Services Officers.

‘In recent years this country has suffered from an unprecedented series of major civil disasters. Wide public concern has been expressed about whether the arrangements, at national and local levels, for dealing with them are adequate. The organisations we represent have made a major contribution to the debate which has taken place over the past year about what improvements are needed.

We are encouraged by the conclusions, announced by the Home Secretary on 15 June, on the preparation of responses to civil disasters. No longer is this to be arranged as an offshoot of planning for wartime civil defence. We are glad that the Government have rejected the idea of a “National Disaster Squad”, recognising that the immediate response can best be left to the emergency services; and that the Home Secretary has extended the remit of the Civil Defence College, renamed the Emergency Planning College, at Easingwold to cover questions relating to civil emergencies in peacetime rather than set up a new institution.

Our organisations will give the proposed new Civil Emergencies Adviser all possible support; but in two important respects we regard the Government statement as falling short of what is required.

First, there is much emphasis on co-ordination, promotion of which is to be one of the new adviser's tasks, but nothing is said about who is to coordinate and under what authority. The police and fire services, health authorities, voluntary organisations, and some not all, local authorities make their own plans, sometimes with, but often without, consultation with one another. But local authorities have no statutory duty to plan for handling civil emergencies or to take on responsibility for co-ordination.

We believe that there is an urgent need for such a duty to be created, and that the co-ordination must essentially involve consultation with industry as well as the other bodies mentioned. We do not agree with the Home Secretary's view that legislation is not needed. It would enable local authorities to ensure that there were no gaps and that proper provisions were made for follow-up action and after-care for those affected. The evident failure of co-ordination in some recent major disasters underlines the urgency of this.

Second, the Home Office statement inspires little confidence in the adequacy of central government arrangements for handling civil emergencies. Key questions remain unanswered. Who will have the responsibility for identifying in advance potential disaster hazards, designating a “lead department” in each case, defining the roles of supporting departments, ensuring that effective contingency plans are made for assistance to local authorities and services; and thirdly that all concerned absorb, and act on, lessons learned from each disaster?

Central government should have, and be seen to have, a clearly-defined role. We cannot afford a repetition of the apparent chaos in Whitehall which followed Chernobyl.

Action in the two areas outlined above should be the first priority for the new Civil Emergencies Adviser.’

Signed

Sir Clive Rose

(Association of Civil Defence and Emergency Planning Officers),

Martin Sibson

(County Emergency Planning Officers' Society),

Eric Alley

(Institute of Civil Defence),

Lord Renton

(National Council for Civil Protection),

Lord Mersey

(Society of Industrial Emergency Services Officers),

Civil Protection Co-ordination Group.’

(The Times, 1 August 1989.)

This correspondence sparked off a Times Leader on the 15 August 1989 and I would like to quote the following:

‘The withholding of proper statutory powers is not without connection to politics. The old GLC (Greater London Council) so politicised emergency planning as to refuse to sanction civil preparations for nuclear attack. The lack of London-wide authority is a legacy of that extremism.

In remedying the London problem, as he urgently must, Mr Hurd should also look again at national disaster planning. He has already decided to appoint a national Civil Emergencies Adviser, ending the long tradition which has treated planning for peacetime emergencies as no more than an accessory to wartime civil defence preparation. He has rejected the dramatic but clumsy concept of a “national disaster squad”, on the grounds that disasters are best tackled by the emergency services already in place locally.

That, however, increases the need for proper back-up and co-ordination between neighbouring agencies, and for clear and logical lines of command and communication in central Government. In an earlier letter in The Times, Sir Clive Rose of the Association of Civil Defence and Emergency Planning Officers headed a distinguished list of experts who expressed “little confidence” in present Government plans for civil emergencies.

They too demanded a change in the law, placing a legal duty on authorities to do what they are now only permitted to do. In local government, the distinction between a duty and a power can sometimes determine whether something is done well or not done at all.

One lesson has emerged repeatedly from recent inquiries into disasters, including those at Zeebrugge, King's Cross, Hillsborough, Clapham Junction and Lockerbie. [Figure 3.2.] In every case the door was shut after the horse had bolted. In every case someone has given warnings which were not taken seriously enough – the “it can't happen here” syndrome – and the necessary steps were taken only after the catastrophe occurred.

The same must not happen in the case of pre-disaster planning itself. Mr Hurd has now been publicly warned by most responsible sources. He should set an example of how those responsible for public safety should respond to such warnings.’ (The Times, 15 August 1989.)

This clamour was further reinforced by a letter from John Horsnell (Chief Executive, Isle of Wight) representing the Society of Local Authority Chief Executives, as follows:

‘Your leading article of August 15 is timely, but the statutory basis upon which local government relies for peacetime emergency planning is even less purposeful than your words imply. Section 138 of the Local Government Act 1972 simply exonerates us for improper expenditure when money is spent in respect of a disaster which has occurred, is imminent or is

FIGURE 3.2 The rescue services attending the aftermath of the Clapham rail crash in December 1988 (Press Association)

reasonably apprehended. Contrast this with the mandatory nature of planning for wartime emergencies under the Civil Defence Act 1948.

But the disasters you mention are not all the same. Some were contained within the works of the uniformed services, others required an input across the public service spectrum. In some instances, like Lockerbie or the great gale, the public perception of a job well done by local government services is believed to be high.

Local government can and does respond to disasters, however they are caused. A statutory obligation to do so has long been urged by chief executives upon the Home Office and would put this essential activity on a par with wartime emergencies and the many other obligations which Parliament has entrusted to local authorities.

Yours faithfully

John Horsnell

Chairman,

Emergency Planning Panel, Society of Local Authority Chief Executives, County Hall, Newport, Isle of Wight.’

(The Times, 15 August 1989.)

The Fire and Civil Defence Authorities

There is the further complication of Fire and Civil Defence Authorities in London and other English metropolitan areas where at present no single authority is charged with co-ordinating the response to a major disaster. I would like to quote from a speech delivered by the Home Secretary in August 1989 which illustrates that he is now willing to legislate to improve emergency planning if only in Fire and Civil Defence Regions.

‘But the response to major disasters is not a static issue. The initiatives I have announced are intended to provide a mechanism by which we can improve and develop our response in the light of experience and wider knowledge. I will expect to see changes and refinements as the work goes forward, and I have been looking carefully at points put to us during the Review in the light of recent emergencies.

As a result of this work, I am now persuaded that there is a possible gap in the provisions for metropolitan areas. And this, I believe, should be tackled now.

In the event of a major disaster in a metropolitan area the emergency services would of course provide the front-line response – as they do throughout the country. They would be supported by the local authority -either a London Borough or a Metropolitan District – and these authorities have their normal functions and resources available and also, under Section 138 of the Local Government Act 1972, can incur expenditure in meeting the effects of a disaster. And Lockerbie in particular has shown how extensive and lengthy that local authority involvement may be.

There is at present no formal system which provides for wider coordination of the local authority response in the metropolitan areas. A major incident would draw heavily on even their joint resources and I want to ensure that the existing arrangements for mutual support between Boroughs and Districts can be properly planned and co-ordinated to provide the most effective response possible.

To achieve this, I intend to give joint Fire and Civil Defence Authorities (FCDAs) a power to co-ordinate the planning of the various Boroughs or Districts. I am now looking for a legislative opportunity.

I should stress that this is a co-ordinating role for FCDAs, not an operational role. And I do not intend simply to extend Section 138 powers to FCDAs. Those County and District councils which have Section 138 powers have them in relation to specific functions and responsibilities -such as emergency housing or social services care. FCDAs do not, of course, have those functions. My intention is to give FCDAs a power to coordinate the planning of the various Boroughs and Districts within their area as a way of assisting the local bodies with the direct responsibilities. As in our new arrangements as a whole, my aim here is to see what we can usefully add to existing arrangements to make them more effective.

In some cases, of course, the metropolitan districts may already have made agency arrangements allowing the FCDAs to act as a co-ordinator in this respect. Those arrangements should obviously be maintained for the present. They will form a sound basis for developing the new role FCDAs will have in co-ordinating local authority planning for emergencies.’ (Home Secretary 1989)

The CEPO Society's agenda

Certainly the Society will welcome the opportunity to discuss with the Civil Emergencies Adviser the following matters; (here I quote directly from a letter written by the CEPO Society President, Martin Sibson, to the Home Office early in September this year) (Sibson 1989):

(i) Phases in the emergency planning process

‘The Review, (of civil emergency planning), quite properly at that time, focused attention upon the response phase and the capacity of the principal emergency services to cope with major incidents. The role of local authorities, other agencies and volunteers in the phases before and after the main event deserves further recognition.’

(ii) Co-ordination

‘The thread which runs through almost every part of the Review is the need for co-ordinated effort at all levels and phases. The machinery to achieve this should be established and the procedures to be observed defined in a code of practice.’

(iii) Legislation

‘There is a need for a close examination of the case for legislation to require local authorities, in consultation with other parties, to make appropriate emergency plans and exercise them.’

(iv) Volunteers

‘The enthusiasm and dedication of the volunteer, whether a member of recognised society, a specialist interest group or from the community, is acknowledged. Their respective roles should be identified, and proposals for their co-ordination developed.’

(v) Liaison with industry and commerce

‘The principle of causation and the responsibility of operators for the off-site consequences of their activities which could affect man or the environment should be recognised. Liaison and consultation with senior representatives from industrial and trade associations, transport undertakings and other “essential services” for the public would be invaluable.

The undoubted success of the Control of Industrial Major Accident Hazards Regulations 1984 as amended and the early experience of the Nuclear Emergency Planning Liaison Group introduced earlier this year are good examples of what is advocated.’ (Sibson 1989.)

Conclusions

I would like to finish with a truism. When reviewing their budgets local authorities will obviously concentrate on statutory duties first before considering desirable but non-compulsory requirements. The financial estimate at the time, the interests of the Public Protection Committee and the perceived risk of Major Peacetime Incidents in the minds of local authority officers will all affect the resources for emergency planning in peacetime. Some counties do little while others have a considerable rate-borne (i.e. non grant-aided) budget. The Society 's view is that legislation is essential to ensure that all local authorities are brought up to a common standard in the preparation of peacetime plans, that suitable liaison is carried out at regular intervals and that appropriate training and exercises occur. Any plan is devalued and is perhaps worthless if it is not validated via exercising at regular intervals. Any plan that is not fully co-ordinated from its inception with all the elements which need to be involved is perhaps not worth the paper it is written on.

Editor's Note

The Fire and Civil Defence Authorities' powers were subsequently amended under the Local Government and Housing Act 1989, Clause 156 (see Chapter 1).

REFERENCES

County Emergency Planning Officer (1988). Initial Report to County Chief Executive, Dorset.

County Emergency Planning Officers' Society (1989). Press Release, July.

Home Office (1989). Review of Arrangements for Dealing with Civil Emergencies in the UK, London.

Home Secretary (1989). Extract from a Home Secretary Speech, August 1989.

Sibson, M. (1989). Extract from letter from President CEPO Society, Martin Sibson, 6 September 1989.