CHAPTER 13

‘Them and Us’: emergency planning and response in a social perspective

Is the continued and increased concentration on post-emergency management itself the greatest impediment to effective emergency planning and response? Can emergency management ever be wholly effective while it excludes pre-emergency management as the crucial response to hazard?

Post-emergency management is often perceived as inclusive of a totality of management for all phases of emergency, both before and after. In the popular exposure that emergency management thus enjoys, it also inadvertently and dangerously absolves all other sectors of their responsibilities with regard to hazards. As a response to hazard management, nothing could be further from reality. This chapter also expresses the concern that the more there is a focus of attention by authorities on ‘emergency planning’, the more separate will planning become from its social context. Emergency management is after all, for people (victims and potential victims) – not for emergency planners; therefore it has to be evaluated from a social standpoint. There is at present, little room for public participation; and emergency planning already tends to be more directed towards major emergencies than towards more frequent minor ones, and on consequences rather than causes arising from the public domain.

Emergency planning, in its conventional sense of planning by a few on behalf of and before what may happen to many in an emergency, can be separated too conveniently from its context. Pre-emergency hazard management extends into management policies of all other governmental and nongovernmental sectors. Is this administratively too difficult to ‘co-ordinate’? Is this the reason why there is no official recognition of pre-disaster management – except repeatedly in post-disaster enquiries? Are we prisoners of convention? Do our ways of thinking have to change before we can merge hazard management and emergency planning and response?

Local authorities and civil defence

Local authorities may now use civil defence resources for emergencies or disasters of any kind, occurring in or affecting their area (Civil Protection in Peacetime Act 1986). Although there is no statutory duty, the principle of local authorities' role in emergency planning and preparedness is thus now reinforced. This is wholly appropriate; national risks are experienced at local levels – where more numerous localised emergencies also occur. The local risk of accidents, storms, flooding, and exceptional snowstorm for example, have the highest local incidence, occurring annually; nuclear accident has not yet achieved that significance.

The Chernobyl nuclear accident of April 1986 conferred awesome reality upon local authority emergency planning. Local authorities (or other authorities acting locally) were involved at the Chernobyl accident zone in fire-fighting and other emergency operations, evacuation, rehousing, decontamination, care of the injured, sick and of evacuees, food distribution, dust eradication, chemical film application, and information promulgation. Within Britain, local authorities were (and still are) involved in environmental, food and water monitoring, livestock control, medication distribution (potassium iodate to reduce the effects of radiation on the thyroid gland), and fallout resurvey (Lewis 1987b).

Emergency and preparedness planning by local authorities for the improved future undertaking of similar activities will be required by statute, as will regional planning to minimise identifiable local sources of risk to communities. In addition to these crucially important undertakings, planning by local authorities could be applied to a wider range of activities for their incorporation into a ‘survival strategy’ for their populations.

Risk and vulnerabilty

Examination of the nature of risk and the concept of vulnerability can help identify useful approaches to hazard management. The condition of risk is not the same as the manifestation of the event that risk purports. The event may be worse, but may be less than our perception of the risk. Our preconception of the ultimate ‘risk’ can cloud our perception of options and measures open to us in the interim. Ideally, we could remove some risks for ourselves, or remove ourselves from them; others may be removed for us by design and legislation. Where risk cannot be removed entirely, we might take action to mitigate or to ameliorate the effects of its manifestation. For example, we can use fire-resistant materials, install extinguishers, and take out insurance. In reality, we might accept the risk and choose to do nothing; risk may remain unperceived or unknown; or more significantly and perhaps more commonly, we might do nothing because there are seemingly no practical options open to us.

Our assessments of the likely causes of events from which risk emanates, will precondition our assessment of risk itself. Risk might be worth taking if survival or recovery were certain or likely; but obscure or inaccurate information may impede accurate perceptions of survival and recovery upon which this kind of assessment may depend. Accurate information about risk will permit appropriate adjustments to vulnerability and response.

Focusing only on risk in its greatest magnitude, has a dangerously distancing effect; and an assessed low risk may seem to condone actions which, when the event does occur, will incur greater effects than were originally perceived. The condition of risk prevails as an interregnum during which developments and regressions involving elements at risk will result in changes to their degree of vulnerability. Thus, where an event occurs, in accordance or not with its actuarial probability, the effects of that occurrence are different at the end of the actuarial period from what they were when the period began. Though reassessable from period to period, actuarial risk is hypothetical and static, but vulnerability is real, dynamic and accretive. It is not only risk, therefore, which needs to be considered, but also vulnerability to risk.

Vulnerability may accrue, therefore, whether or not risk is appropriately perceived. Vulnerability is actual whereas risk is actuarial. But by the same token, as the result of developments either strategic or fortuitous, vulnerability could be made to diminish or be held in check.

Risk is defined according to an event of a total assumed magnitude. In the actual event and location, the magnitude, and impact may be greater, lesser, or partial. Vulnerability comprises the variety and number of populations, settlements, dwellings and activities, each contributing as elements of the overall vulnerable condition. Perception of the total risk may be so painful or intensive a consideration as to presage the very circumstances which might otherwise be mitigated. Perception and assessment of vulnerability on the other hand, relate to that variety of elements as parts of the total condition, which are thus more comfortably and constructively considered.

Risk is an assumed totality of an event brought about by external forces over which we may have no control (or over which we have lost control). Counter-measures against risk are therefore conceived as separate from normal activities, powerful and massive, and thus usually costly. Inevitably, risk is interpreted in mathematical, physical and economic terms. Vulnerability, on the other hand, is partial, accretive, and has to do with location, age, strength, socio-economic level, integration and accessibility. Measures to reduce vulnerability are also partial, and are integrative, small-scale, and individually and comparatively are not costly. Vulnerability is essentially a social concept, applying physical, economic and infrastructural elements within a social context.

Consideration of options with regard to perceived risk are thus limited by interpretation of the risk. Big risks need big options of which there will be few. Consideration of small-scale elements of vulnerability needs small-scale options of which there will be more. Opportunity at community and domestic levels to take action against vulnerability to risk, is thus increased and made more accessible. Local self-reliance becomes more feasible.

Local self-reliance

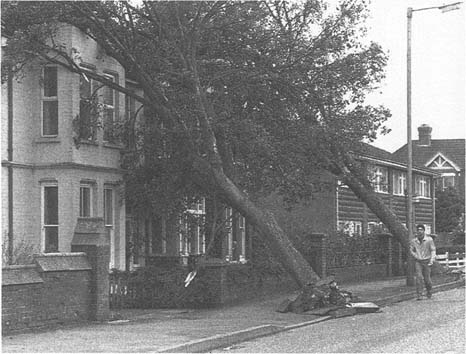

The needs of victims in emergencies must be distinguished from the needs of emergency services. Some needs of victims will be provided by emergency services; but some will be met by self-help, self-reliance and initiative. At the Flixborough explosion in June 1974, those who survived were those who did not congregate in the control room in response to emergency procedures. Many in the Herald of Free Enterprise sinking in March 1987 were saved by the initiative of others before the arrival of emergency services. In the aftermath of the October 1987 gales in Britain (Figure 13.1), those who already had alternative fuel supplies, were better able to ‘survive’ than those who were wholly dependent on emergency distributions or the eventual repair of power lines. Poignantly, had the ‘vagrant’ been housed, and had the wall under which he slept been adequately maintained, one death would have been avoided in the same storm.

Vulnerability reduction

Strategies for local self-reliance and survival do not have to wait for risk to become imminent. Indeed, they cannot; but all social, commercial and economic activities contain the opportunity in their normal processes of change and development to incorporate consideration of local emergencies and their aftermath, and to be modified accordingly. Integration over time of the concepts of vulnerability and survival would be as effective, if not more so, than making only those provisions which are possible in a short warning period.

Public and social services are required by all communities, regardless of size. Needs of these services are at their greatest in the random direct or peripheral effects of any accident, fire, flood or storm. The smaller the scale of the event, the more frequent it is likely to be; the more frequent it is – the nearer the normal it can be said to be. Therefore, it is not only the projected, unique or rare event we should plan for, it is normal and local vulnerability.

Planning for this concept of emergencies, is not the function only of a special or separate organisation. Planning for the accommodation of risk is best implemented by reducing the vulnerability of elements and potential victims at risk, wherever they are and from whatever hazard. This kind of planning is best undertaken within each and every sector of activity and undertaking. In emergencies, no-one can be sure of access to available resources; but everyone has a wide variety of needs which are common to all events and which are therefore known. Health-care, education, public transport, housing, post offices, public telephones, libraries, newsagents, pharmacies, food shops and public houses are all relevant towards the creation of a pervasive, local, accessible, comprehensive service system for the enablement of recovery and survival for communities and populations – from whatever hazard and whatever perceived risk (Lewis 1987a). Fire, police and ambulance services are additional to these resources and are required to be similarly locally accessible.

The centralisation of services deprives areas peripheral to the centre. The larger the administrative area, the greater is the number of people at a greater distance from the services or resource they require. Services for disasters and emergencies need to be decentralised on the basis of potential local need – not centralised on the basis of economy of scale. It follows, therefore, that a given type and magnitude of disaster will have a different effect according to the vulnerability of the area upon which it impinges; and the response of that area and its ability to survive and to recover will similarly be variable according to its resources and their management prevailing before disaster occurred. ‘Risk’ is not only to do with the magnitude or type of the disaster force; yet repeatedly risk magnitude is portrayed as such. Isolines of risk values are superimposed upon maps of inhabited areas in concentric and parallel circles unrelated to the settlement pattern or infrastructure and related only to the source of explosion or emission. This kind of approach is over-simplified, mono-disciplinary, technocratic and institutionally oriented. It makes no allowance for community management or response or improvements to response capacity or resources over time.

Where measures are taken to reduce vulnerability, it will be to the enrichment of society at large – and for the long-term accommodation of hazards of whatever kind and of whatever scale. The ‘effectiveness’ of a wider interpretation of emergency planning and response will be improved by local access to resources – as well as improved access by emergency services. Vulnerability isolines take into account location of habitation and settlement; age, structural condition and use of buildings; area density of habitation; indicators of economic level; accessibility of emergency services and access to services and resources. Additionally, prevailing wind would condition vulnerability for some to some sources of risk (e.g. fire; pollution; fallout). Isolines of vulnerability to various hazards respond to additional topographical, socio-economic and climatological factors. Clearly, vulnerability in an area of high risk signals a greater potential emergency than vulnerability in a low-risk area; degrees of vulnerability conditioning potential disaster according to degrees of risk to which they are subjected. Overlay mapping would be an appropriate technique; the greatly increased amounts of field information required for vulnerability mapping being a reflection of the relative separation of risk mapping from those who are at risk.

It also follows, therefore, that for a community not to acknowledge and to accommodate risk will be to do a disservice to the quality of life (Lewis 1990). Not because the risk in question would destroy that quality (it may never happen) but because the adjustment required to counteract risk will in many cases be an improvement to everyday services, resources and infrastructure as well.

This is too crucial simply to delegate to an external and specialist organisation. No single institutional body can be responsible for all these local needs. They have to be provided as part of overall development policy. Many will be the product of national authorities and institutions operating and working locally. Each local provision would be accessible and available for all needs, in major disasters, in localised emergencies, and in the general improvement of the quality of life in the interim.

National policy for emergency planning and management has to include support for development of locally accessible resources, self-reliance and initiative. Training and education and local infrastructures have to be developed with a normal possibility of hazards, disasters and emergencies in mind.

Incumbent management

Shortcomings and failures of incumbent management (Turner 1978), as distinct from management of external emergency services, frequently have been identified as contributing to the causes of ‘accident’. Management has been blamed for causing, or contributing to the cause of, the 1973 Summerland fire (Isle of Man); the May 1985 Bradford Stadium fire; the November 1987 King's Cross fire; the Herald of Free Enterprise capsize in March 1987; the Hillsborough football crowd disaster in April 1989; the Camelford water supply poisoning of July 1988 and the Clapham railway signal failure and collision of December 1988 – to name but a few.

Aspects of incumbent management that have led to disasters have often been so elementary as not to be associated with ‘emergency management’ at all. Examples include the accretion of rubbish and garbage removal (Bradford and King's Cross fires) and the locking of emergency doors (Isle of Man and Bradford fires). These matters rarely come within conventional interpretations of ‘emergency planning’; yet it is these matters which create or exacerbate demand and need of emergency services. It is thus inevitable that attention focused only upon emergency services, will be outclassed by inattention to incumbent management. Increased cost and resources for emergency services on the one hand, will be wasted where this imbalance of attention is perpetrated by the other hand. Thus in the same authority, one hand can be the cause of what the other hand is paying for.

Research management

Conventional emergency planning is an arguably convenient approach to conventional disasters and emergencies. Before Chernobyl, nuclear accidents of international significance had barely been envisaged. What are the disasters of the future? The Piper Alpha oil rig explosion and fire of July 1988 in which 167 people died, was a first in British waters; new technologies bring new risks. In addition to known specific threats, what unknowns hold future emergencies?

Presentation and interpretation of case studies for hazard and emergency management require research for their articulation, as well as for their integration at local levels. Research will most appropriately be within a university or polytechnic within a multidisciplinary context and adjacent to the necessarily wide range of relevant studies: environment; geography; planning; law; engineering; architecture; management; and sociology. Emergency management will not best be served by its separation and containment within a special college created for the purpose (Lewis 1988).

Studies in natural hazards, risk and emergency management, disaster vulnerability, and disaster preparedness, are permanent areas for study in universities and polytechnics world-wide. These studies are long established and advanced in the United States, Canada, Australia, Japan, and in some European and Scandinavian countries. Overseas initiatives are promoted by governments of these countries, and others. Third-world countries are served by the Asian Disaster Preparedness Centre at the Asian Institute of Technology in Bangkok; the University of the West Indies, and regional initiatives of the World Health Organisation, the United Nations Office of the Disaster Relief Co-ordinator, and the United Nations Regional Commissions.

Britain is a relative newcomer to domestic applications of this subject area. Is the formidable series of national disasters a reflection of this state of affairs? A National Centre for Disaster Studies would now not be a step too soon or too far.

REFERENCES

Lewis, J. (1987a). Vulnerability management – the translation of risk into planning decisions. Paper presented at the IFHP-IULA Symposium, Rotterdam: Prevention and Containment of Large-scale Industrial Accidents.

Lewis, J. (1987b). Risk, vulnerability and survival: some post-Chernobyl implications for people, planning and civil defence. Local Government Studies, 13, 4, 75–92.

Lewis, J. (1988). Civil Emergencies: invited comments on the Home Office Discussion Paper of June 1988. August.

Lewis, J. (1990). Accident or Design? Review of the Royal Institute of British Architects Report Nuclear Disasters and the Built Environment. RIBA Journal, July, 34–35.

Turner, B.A. (1978). Man-made disasters. Wykeham, London.