15

Strategy for Breakfast

It is commonly said that ‘culture eats strategy for breakfast'. I daresay this is because breakfast is the most important meal of the day, and good strategy is so nourishing.

Just because we have a potentially brilliant strategy doesn't mean we can then simply make upward flapping gestures at the rest of the organisation and say, ‘Make it so!'

Strategy needs to be communicated effectively — and frequently.

And just like you don't hide a good breakfast right at the back of the cupboard, you don't hide good strategy behind layers of hierarchy, or buried deep within bloated PowerPoint presentations or documents on the intranet.[1]

BUT CHANGE IS GOOD, RIGHT?

In theory, yes, change is good. But in practice — not necessarily. At least, not for everyone. Some of the ‘stop' decisions from the previous chapter may mean making tough decisions, which could mean redundancies and a cutting back of investment in some business units. These tough decisions are normally dressed in corporate code — we use terms like ‘downsizing', ‘productivity' and ‘working smarter' to explain what is also people losing their jobs.[2]

But — if you're playing your cards right — this type of thing should actually come as little surprise to your people. You'll have been openly communicating on internal platforms, and sharing learning and the collective hunches about where the enterprise needs to turn to. You'll be supportive of intrapreneurship, and will have been dialling up the efforts of internal experiments. When people hear of the new strategic direction, it will make a certain kind of sense (thanks to the extensive monitoring of the drivers of change, and the accumulation of evidence via internal experiments).

But! If people are ambushed by change — if they don't understand, appreciate or connect with the direction that is set, or the purpose informing it (the ‘why') — that change will very likely be resisted.

When goals and targets shift autocratically, or when leadership is perceived to lack the conviction to truly lead courageous, game-changing and pioneering strategy, or when deep-seated cultural issues[3] have not been addressed, then we'll see people defaulting to their defaults. We have a finite amount of time, energy and attention each day, so investing our efforts in things that provide a sense of progress makes sense. If people can't find meaningful progress in their work, they'll try to find it in other things — like micromanaging direct reports, making spreadsheets, or playing Candy Crush.

John Kotter (Emeritus Professor of Leadership at the Harvard Business School) has identified some common dysfunctional patterns among leaders driving change. In one such pattern, leaders actually do a very good job of capturing a pioneering strategy and vision for transformation — but then they proceed to communicate this vision in a single conference or meeting, or through a single missive. ‘Having used about 0.0001 per cent of the yearly intracompany communication budget, the group is startled that few people understand the new approach,' Kotter observes.

In another pattern, much more effort goes into meetings, newsletters, ‘town hall' presentations, open Q&A sessions, and so on — but some very visible senior leaders still behave in ways that are incongruent with the new vision. The result is more cynicism within the workplace culture, and increased distrust in leaders and their communications.

When translating strategic decisions into meaningful progress, transparency, and authentic communication in leadership is critical.[4] Quest-Augmented Strategy thrives in a networked enterprise, in which communication can easily occur across all elements of the business.

NETWORKED ENTERPRISE GOODNESS

In 1992, anthropologist Robin Dunbar published a groundbreaking paper exploring the cognitive limit to the number of people with whom we can maintain stable social relationships. The optimal group size lies somewhere between 100 and 250 people (with the commonly used value being 150).

When the total number of employees in an enterprise grows beyond 150 people, this likely also comes with cultural implications. Things begin to take on more of a rigid, corporate feel.[5] It's insidious. New policies and procedures get introduced, and things begin to feel more ‘structured'. For those who value operational efficiency,[6] this could be a welcome change.

But those who value connection[7] will lament the additional barriers and friction that begin to get in the way of communication and relationships. Where once the workplace felt like working with friends (your ‘second family'), it now feels institutional and less human; less organic and more clinical.[8] At its worst, we have a risk-averse, rule-bound, lifeless and impersonal organisation in which people file in like drones to tick boxes, follow instructions and churn through default processes — and where the only way to advance things is to play political games with those in positions of authority, higher in the hierarchy.

Translating pioneering strategy in this extreme would be … difficult.

So what's the solution? Break down all silos? Completely flatten all hierarchies?

Maybe. But as hip as such an approach might sound in our current Zeitgeist, it's fairly dramatic, and could require massive reorganisation. And the risk of such an approach is that we'll end up in a similar predicament a few years later.

And besides: silos can be efficient (although ‘hub' is perhaps a better concept to embrace).[9] Silos still have an inherent hierarchy within them — which can be fine, if the numbers are small enough and the leadership is good. But this can be equally terrible. A hub (like a silo) groups people according to their expertise/function/location. But, unlike a hierarchy, no barriers exist to informal relationships. Here, people turn up and pitch in to the work that needs to be done. They help each other out, discuss better ways to do things, and get on with the good work of making meaningful progress.[10]

HYDRA DOMINATUS

Here's another way to consider your organisation in a networked context. Have a look at your org chart. If it fits on a page, or if it seems to have a strong sense of order to it, you don't have a networked enterprise. Instead, your enterprise is likely too hierarchical and structured.

Your enterprise is possibly strong and robust — things that were of value during the factory era, in which the work was formulaic and operational efficiency was paramount. In this context, the default approach to organising the work of an enterprise was to create structure and rules to unlock economies of scale.

But in our current and emerging context, robust is actually quite fragile.[11] Like an iron sword, a robust enterprise can break.

The alternative is to shift towards a more ‘antifragile' or responsive organisational structure. Antifragility is a term coined by risk analysis and scholar Nassim Nicholas Taleb to describe a state beyond resilience or robustness. Where resilient systems resist shocks and stay the same, antifragile systems get better.

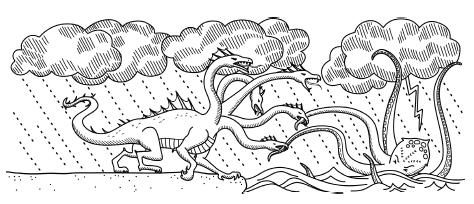

Think of it like the hydra — the mythical multi-headed beast. Chop one of its heads off, and two grow back in its place. Even the Inevitable Kraken of Doom can't stomach the antifragile hydra.

Such systems thrive on disorder and change, thanks to an inherent bias towards learning and adaptability. They have in-built, non-linear redundancies and backup plans that only get better with exposure to more external stressors. They are stronger for being tested.

Naturally this is all very exciting, but does this mean we need to throw out all of the structures we have? And, if so, where do we even start?

Why, with a quest of course.

Any large incumbent enterprises ought to be exploring more responsive ways of working.[12] What does this involve? Gathering options, conducting experiments and making strategic decisions that enable enduring relevance and growth. If you're savvy about the incoherence of an unresponsive organisation, it'll become a mighty important thing to monitor and explore.

The more progressive an organisation becomes, the more the distinctions between the quadrants in Quest-Augmented Strategy become blurred. This is part and parcel of a networked organisation.

Within networked organisations, you need to consider two main elements:

- Clustering. This refers to the degree in which you have hubs or nodes — tightly knit groups where collaboration occurs naturally, due to a shared proximity and/or focus. If the hierarchy is rigid, you might call them silos. But if you have distributed authority, transparent communication and minimal management, you might think of clusters as the (antifragile) hubs or nodes of your enterprise network.

- Path length. This refers to the number of links separating any two nodes within the network.

We frequently hear talk about ‘breaking down silos' — but doing so might threaten the efficiency and power of our tightly knit collaborative hubs. A better thing to focus on is reducing the path length between hubs. This is where we seek to minimise the friction between disparate nodes and hubs. By doing this, we open up the opportunity for more informal relationships and connections to occur between nodes — and, as a result, the enterprise as a whole moves closer towards a state that is more responsive and adaptive to pioneering strategy.

The quickest way to do this? Through your internal communication platforms.

A good internal communications network will effectively punch holes between nodes. Where connections in a traditional enterprise might otherwise take weeks or months to establish (by the time you wade through hierarchy, permissions, time differences, and so on), an effective internal communications network could see that same connection happen almost instantly.

This allows intrapreneurial hubs to form organically, and to easily rally together (no matter their function or geographical location) in order to progress the pioneering projects that matter.

Of course, such gains will only happen if strategic intent is translated into the leadership behaviours that matter (see chapter 19), and when coupled with rituals that transcend barriers (like conferences that pull folks together — see chapter 21).

These ideas bring us back to our quest, and the hero's journey.

THE BIGGER QUEST

Leading a quest ought not be restricted to a small pocket of pioneering leaders within an enterprise exploring alternative strategic pathways.

Sure, it might start like this. But if you recall the final element in the hero's journey, at some point the hero returns to the ordinary, default world, bringing with them special insight to inform and progress pioneering strategy and growth.

Part of this insight is the pioneering strategy. The other part is the pioneering leadership, in which we can create an environment in which anyone can embark upon meaningful quests.

Imagine one of your frontline staff hearing about a frustration from a customer. Instead of just being efficient — quickly dealing with the frustration and then carrying on with business as usual — they get curious. In a short time, they uncover a similar frustration from another customer. A hunch is formed, and they begin to explore. They discuss this with their team — turns out others have noticed a similar frustration. Now a few folks are on the quest, exploring what could be a minor opportunity for strategic advantage. After continued monitoring and many conversations via internal communications, the problem becomes quite clear — a big gap exists between the current offering (or modus operandi) and an emerging market need.

The team reaches out to folks in a similar role in different countries. A special-interest project is created — a virtual hub of activity within the internal network. Articles and ideas are shared, and the drivers of change are monitored. Strategic options begin to appear. Small, smart, safe and short experiments are conducted, and new insight is rapidly obtained. By now, other leaders within the enterprise are aware of this quest. Because curiosity and intrapreneurship is valued, they figure out a way to support increasingly large experiments — directed by those within group. The experiments continue; some ‘fail', but all yield profound new insight and learning for the group.

Meanwhile, the time for a senior leadership retreat is getting closer, and potentially integrating the new strategic option (while dialling back other areas of the business) appears to be quite a viable alternative. And so key leaders (easily identifiable from the internal communications platform or network) are invited to contribute to conversations leading up to the strategic retreat. New concerns and ‘what ifs' are thrown at them, to which they are able to quickly gather new intelligence and responses. By the time the leaders meet, the decision to integrate this new strategic option into the main enterprise strategy is pretty clear. A path is chosen, and a new default is formed.

Because this happened via a transparent communications platform,[13] the new shift comes as no surprise. And because this strategic pathway originated from the frontline, a whole heap of empathy comes with it. The result? Everyone wins, and meaningful progress is made.

Now imagine if that were the norm. Imagine if curiosity — and the gumption to pursue meaningful progress — was the default across all units in your enterprise. Imagine if authority and autonomy were distributed appropriately, empowering connected hubs to work together to pioneer new growth and unlock enduring (antifragile) relevance.[14]

Speaking of progress …

IT NEEDS TO START SOMEWHERE

Quest-Augmented Strategy is a framework to enable better strategic decision-making and leadership. It enables a more pioneering approach to enterprise growth.

But this can originate at any level within the enterprise. Even if you feel as though you're currently just a tiny speck within the belly of a behemoth enterprise, ways to build and demonstrate pioneering leadership are available.

In part VI we shift our focus to progress — or, more specifically, to how we get on with the doing that's required to make meaningful progress.