WE OCCASIONALLY NEED TO REMIND OURSELVES THAT WE’RE NOT AS EFFECTIVE WHEN WE LET ONE ASPECT GO.

One of the benefits of having the studio attached to our house is that there’s really no division between life and work. Naturally, this isn’t always a good thing. But where inspiration is concerned, it allows for a kind of organic relationship between thinking and talking and making things. So, if we’re at the dinner table and we have an idea, the studio’s right there. Jessica keeps a sketchbook in pretty much every room in the house in case she doesn’t make it to the studio in time. It kind of works like this: Jessica draws. Bill reads. Jessica starts at 5 AM. Bill ends at 3 AM. Combined, we get a lot of ideas by working a very long workday.

Years ago, a doctor characterized Bill’s personality as one of indiscriminate longing. It’s actually pretty accurate, and although occasionally maddening, it means that everything is grist for the mill. Books in our library—a library that spills out into every room in the house—are a kind of extended canvas for us, feeding that longing and providing material for the endless list of projects we haven’t gotten to yet. So, in a sense, the library is the best kind of memory vault, because it’s both reliable as a research source and expandable as our interests—our longings—grow.

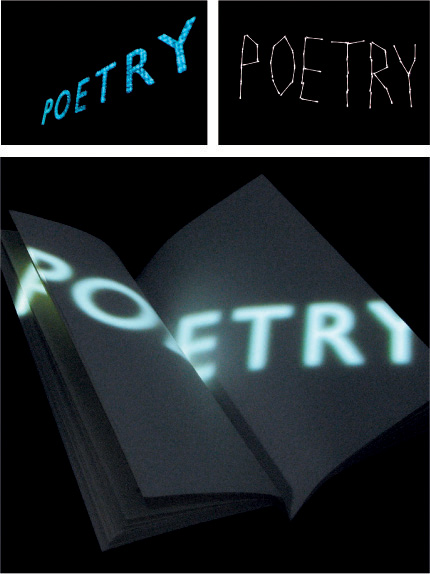

We started small with our concepts around poetry, just playing with the word poetry—literally, projecting it on the ceiling, sketching it in cotton swabs, and photographing it in votive candles—and it occurred to us that this very playfulness might enable the concept to reveal the many sides of poetry. We called this phase the “poetry is all around us” model.

The line between influence and imitation is a slippery slope, and it’s one that we all struggle to comprehend. It’s a particularly vexing proposition when you feel you’re imitating yourself: Are you being consistent or boring? We argue endlessly about this, and it is possible—even likely—that as difficult as those arguments can be, this is a debate that benefits from having two partners: We like to think we keep each other fresh and honest. That’s not easy, particularly as we have very different approaches to work—one of us is focused like a laser beam, and the other one? Well, let’s just say that Jessica was recently described as an abstract expressionist. (This was in relation to a template.)

Where our work is concerned, we’ve found the most significant shift to be brought on by Design Observer, which permits discussion, but also recognizes the power of writing as an intrinsic part of both creating and consuming design. Our recent expansion of Design Observer not only reflects our perceptions about this more expansive, integrated, multidisciplinary view of design, but also is a response to our readers’ increasingly varied interests. (It’s also the fulfillment of what we initially envisioned—that Design Observer could cast a wider net on design as a humanist discipline.)

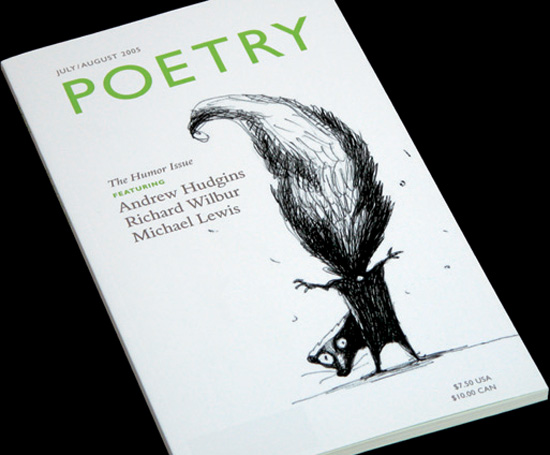

Our work for the Poetry Foundation began as a simple exercise: How do you make poetry accessible, visual, and interesting? How do you reflect its lyrical breadth, its intellectual rigor, its humor and scope?

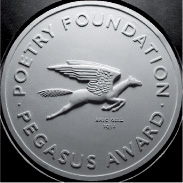

Phase Two was the Pegasus. We had a copy of Poetry magazine from 1931 with a Pegasus drawn by Eric Gill. Further research revealed a number of artists—from Rockwell Kent to James Thurber—whose drawings of the winged horse led us to consider ways of incorporating the entire series into the program, which we did.

And on it went: collateral materials, a website, an online poetry tool, a magazine, a medal cast in bronze. The finished project, as it were, is ongoing.

The poetry project is an example of something that evolved through experimentation and exploration in the studio over a number of years. There was no premeditated concept, though when we realized that the word poetry was our raw material, we unleashed a new way of working, in which experiment and evaluation were intrinsic, parallel methods. For something as vast and intangible as the idea of poetry, this was an unusually gratifying process, and over time we were able to break it down into its component parts.

The most gratifying projects for us are the ones that involve research, writing, drawing, and experimentation. Poetry was all of that. We occasionally need to remind ourselves that we’re not as effective when we let one aspect go; put another way, the more complex the problem—the more seemingly impossible, intractable, and nonvisual—the more we’re hooked.

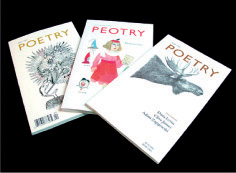

The magazine, for example, uses illustration, always silhouetted on white, on its cover: The illustrations have no bearing on the content, on the meaning of the featured poems; which enables another kind of form, a visual kind of poetry, now played out over fifty issues.

WINTERHOUSE

WINTERHOUSE