7

Strategic Moves

Mechanisms for Market Entry and Dominance

Key Topics Covered in This Chapter

- Gaining a beachhead in occupied terrain

- Using innovation to overcome barriers to entry

- Gaining market entry through product differentiation

- Creating and then dominating a new market

- Enlisting the power of product/service platform

CHAPTER 6 IDENTIFIED the most common strategy types: low-cost leadership, product/service differentiation, customer relationship, and the network effect. It also pointed out instances in which innovation has helped companies apply them successfully.

There’s much more to strategy than deciding which version or variant of these strategies is best for your company. This chapter continues the discussion, indicating how strategy can be used to enter and build defensible positions in the marketplace. It explores a number of potential strategic moves. The discussion here is selective owing to the “essentials” nature of this book. But they should get you thinking about what your company might accomplish.

Gaining a Market Beachhead

In his classic book on military strategy, On War, Carl von Clausewitz told his readers that “Where absolute superiority is not attainable, you must produce a relative one at the decisive point by making skillful use of what you have.”1 Von Clausewitz’s advice reminds us that the strategist must reckon with the realities of the market and the existence of competing firms, some of which will have greater market power and financial resources. This means that one must strike in an area of competitor weakness, where the competitor is unlikely to fight back, or where it will fail to fight back effectively. The strategy chosen, then, must be made in view of this situation.

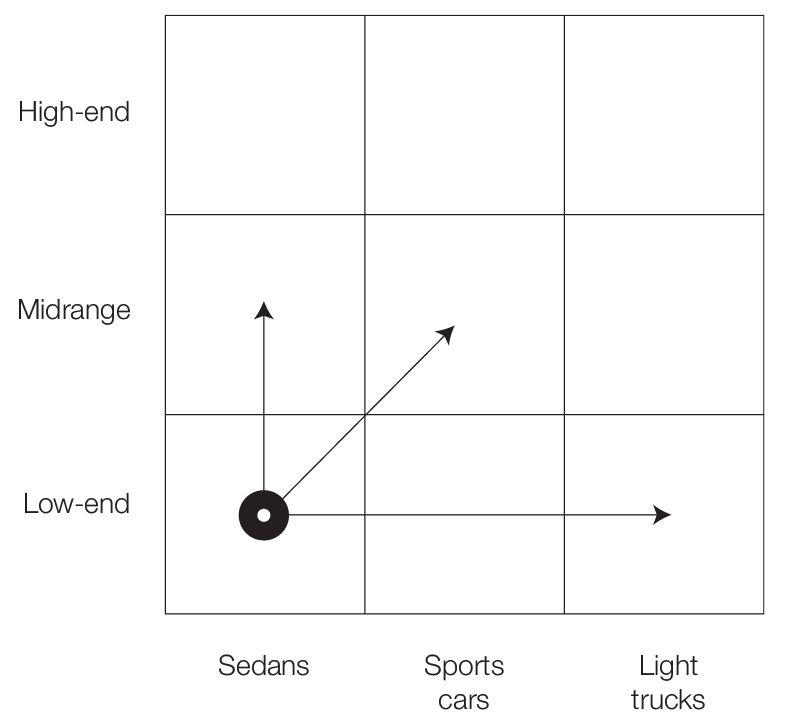

Consider the case of the U.S. auto industry during the 1960s and 1970s. None of the domestic automakers of the time were skilled at producing small, fuel-efficient vehicles. This was not the result of engineering ineptitude; there simply wasn’t strong demand for small cars in the United States. Fuel prices relative to incomes were very low, and most consumers liked roomier vehicles. Also, profits on the few small cars made or sold in America—both in terms of margin and absolute dollars—were far lower than those obtained from larger vehicles. Detroit automakers said “Why bother?” to small cars. Lacking products from domestic producers, customers who wanted small cars gravitated toward small foreign manufacturers. The Volkswagen Beetle had already become something of a statement among students, the thrifty, and antiestablishment types. Before long, Datsun, Fiat, and Renault brought their small, economical vehicles to the low end of the huge U.S. market where they had, in Clausewitzian terms, relative superiority, and where they were largely unopposed by domestic producers. Toyota, Mitsubishi, Honda, and others followed and successfully established themselves. The fuel shortages and gasoline price spikes of the 1970s gave these small-car makers a huge boost and positioned them to move upstream into larger, more profitable segments. Figure 7-1 indicates how foreign producers, particularly from Asia, moved strategically from their initial beachheads into different market segments, mostly into the midrange. By the 1990s, some of these producers were introducing cars like the Lexus to challenge the high-end, profit-rich sedan segment; and they did the same in the fast-growing light-truck category.

Asian watchmakers followed a similar approach in the early 1970s when they entered the low end of the personal timekeeper market, where unit sales were potentially large but profits were small, and opposition from the dominant companies was weak. Precision watchmakers were unwilling to contest the Asian companies in those low-margin markets, but were content to retreat into the upper-end, high-profit segments of the market. Once the newcomers had established a beachhead, however, they developed products for those high-profit segments as well, forcing established European and North American producers to either compete more intensely or fold.

Moving beyond the beachhead

The lesson in both these examples is to follow Clausewitz’s timeless advice of aiming the sharp end of the spear where rivals are weak or uninterested in what you’re doing. That advice is applicable in just about every industry. Sam Walton, for example, did not initially go head-to-head with Sears or J.C. Penney, the retail giants of his day. Instead, he located his new Wal-Mart stores in small towns that were not served by those formidable rivals.

Think for a moment about the segments in your industry. Draw a map similar to figure 7-1. Which are the undefended segments where you could establish a beachhead? Once a beachhead is established, what would it take to expand into more profitable adjacent segments?

Market Entry Through Process Innovation

Some entry barriers cannot be outflanked as described above; they must be confronted directly. A direct confrontation with an established competitor is bound to be costly and dangerous. The better approach is to bring an innovation to the market—something that will turn the strengths of entrenched rivals into weaknesses.

Consider the example of the “mini-mill” first developed by Nucor Corporation, a newcomer to the industry, under the leadership of Ken Iverson in the 1980s. At the time, steelmaking was a mature business requiring huge capital assets and supply chains that stretched back to distant ore- and coal-producing operations. Sheet steel was produced through a batch process that poured mattress-sized slabs of white-hot metal and then gradually reduced slab thickness through a long and expensive series of rolling mills and reheating operations.

Nucor’s innovation was to license a then-unproven German technology for continuous casting of thin metal slabs. This process needed very little milling or reheating. Nucor also opted to use scrap steel melted in electric furnaces as its raw material, eliminating the need for steel production from ore. Continuous casting had been an objective of steelmakers for almost a century, but until Nucor’s bold gamble, no one had been able to make it work on a commercial level. In Nucor’s hands, the innovation not only worked, but it ultimately cut the cost of steelmaking by more than 20 percent and provided Nucor with a successful market entry. Thanks to its innovative “mini-mills,” the company has become the largest U.S. steel producer and is consistently profitable in an industry plagued by wide swings in customer demand. Its return on invested capital is a stunning 25 percent. “Big Steel,” in contrast, discovered that its strengths—huge plants and labor forces, mining operations, and so forth—were now weaknesses.

Whether yours is a product or service company, process innovation may be your ticket to entering or gaining dominance in your target market. Have you or anyone else in your company given this approach any thought?

Market Entry Through Product Differentiation

Product differentiation is another strategy for gaining a market foothold. Inventor Edwin Land and the company he founded, Polaroid, did this in the photographic imaging business. During the 1950s, when Land was developing his technology, the photography business was already mature. Kodak dominated that business and many of its niches. Land would never make headway by producing his own brand of traditional films and cameras; that market was already well served. So he differentiated his product, creating a film capable of developing itself in one minute. This was new, this was different, and it set Polaroid apart. “Instant photography” was a big hit with many consumers, so much so that it allowed Land’s company to flourish for decades until it was laid low by innovations in digital imaging.

To be successful, product differentiation must be valued by targeted customers. That’s fairly obvious. But it must also be protected by patents or proprietary methods that make its duplication by rivals difficult or impossible. This is an aspect of differentiation that many overlook. George Eastman, founder of Kodak, hit the mother lode with his innovation of photographic film on a roll of cellulose. But Eastman went a step further. Understanding how easily his product could be duplicated by others, he protected it and the equipment he developed to manufacture it with an impenetrable thicket of patents. That protection helped his company stake out and dominate the photographic film business for generations.

Eastman’s level of success is difficult to replicate. Most product differentiators are lucky if they can capture more than a two- or three-year monopoly. Consider the experience of Minnetonka Corporation, a small, Minnesota-based firm that introduced a product called “Softsoap” to a mature market dominated by huge national corporations. Softsoap came in a small plastic bottle with a handy pump. Liquid hand soap making isn’t rocket science. Anyone with a small laboratory and rudimentary knowledge of chemistry can develop a marketable version of it. In fact, the first liquid soap developed in the United States received its patent in 1865. Over a century later, in 1980, Minnetonka introduced and branded its own version, which was a big hit. Any one of the big soap producerdistributors—companies that controlled shelf space in retail stores across the continent—could have introduced a rival version and smothered the upstart innovator under a tidal wave of promotion and store incentives. But Minnetonka had taken steps to protect itself in the short term by buying up the entire supply of plastic pumps needed for the liquid soap dispensers. That held the competition at bay for a while. Eventually, in 1987, Minnetonka Corporation sold its liquid soap business to Colgate-Palmolive, which has extended the brand with many product variations.

Create and Dominate a New Market

Are you struggling to match or outperform your rivals on cost, quality, or features? That might be a loser’s game. A better approach might be to invent an entirely new market where no competitor has yet ventured. (See also “Breaking Free of the Old Formula.”) And if you blanket key niches of that new market with good products or services, you will achieve a level of dominance that raises high entry barriers to others.

Breaking Free of the Old Formula

Success is often a barrier to market innovation because it enforces a formula that hamstrings innovation and change. For example, back in the late 1970s, the computing world was dominated by powerful mainframe computers, and IBM dominated that business. So, when personal computers began to appear, there wasn’t a lot of interest within IBM. The people with organizational clout and big budgets were mainframers who understood how to make big computers and distribute them via corporate leases. Desktop computing and the selling of small, inexpensive machines to individuals were alien ideas within IBM. The only way the company could get its first PC into the market was through a skunkworks of engineers it set up in Boca Raton, Florida, far from the company’s center of power.

Sometimes the best way to break free of the old formula and address a new market is through a new subsidiary or new operating unit that has been given substantial autonomy—and no rule book.

Consider Sony, which conceived of the personal portable stereo market and a product for tapping it: the Walkman. First introduced in 1979, the Walkman gave consumers great sound at a low price, in a small package that could be carried in a coat pocket or briefcase or attached to a jogger’s waistband. No boom box could rival it for portability and sound quality. Millions of commuters, music buffs, joggers, and people stuck in office cubicles from nine to five bought them. To fill the many segments of this new market and thereby achieve dominance, Sony introduced different versions of the Walkman, almost all based on the same product platform: a more rugged sports version, one that included AM/FM radio, and so forth. And though rivals soon entered the market with versions of their own, Sony remained dominant and continued to introduce new models. It held that position until the advent of digital recording and playback devices.

What Sony accomplished decades ago has today been leapfrogged by the Apple iPod, a pocket-sized digital sound system capable of storing thousands of music files. These are fast becoming a must-have item for music lovers of all persuasions. Between its market launch in October 2001 and late 2004, consumers snapped up 5.7 million units.

Like Sony before it, Apple now offers iPod variants for different market segments, all based on the basic product platform (a form of incremental innovation). As of mid-2008, these included the iPod Shuffle, a 1- or 2-gigabite device capable of storing hundreds of files, the iPod Nano, a 4- or 8-gigabite unit with a 2-inch video screen, and the more powerful 2.5-inch-screen iPod Classic.

To create a new market, shift from building and making products to something more basic: satisfying customer’s most pressing needs in new ways. Ask, “What could we offer customers if we forgot everything we know about our industry’s current rules and traditions? How might we combine the advantages of several industries’ offerings to provide new value for buyers?”

Throwing away the rulebook and starting with a clean slate isn’t easy—especially if you’ve been successful under those rules—but it’s the only way to think your way to new, competition-free markets.

Extending Innovation Through Platforms

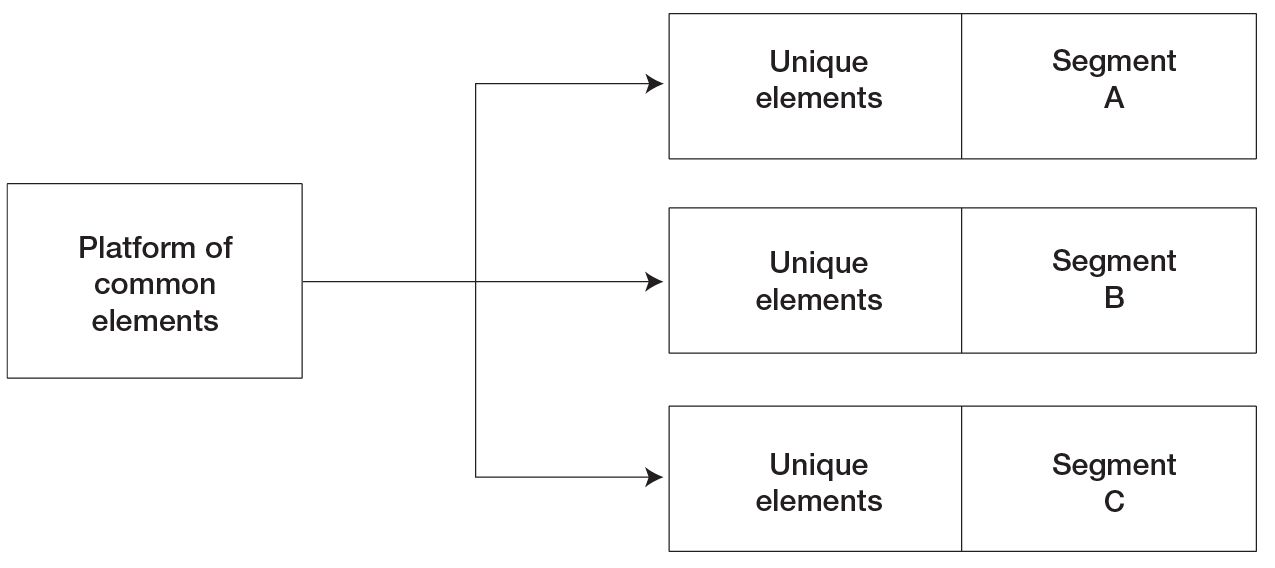

The concept of product platform is another powerful strategy for extending innovation into the market. A product platform, as described by Marc Meyer and Al Lehnerd, whose work has largely defined this important concept, is “a set of subsystems and interfaces that form a common structure from which a stream of derivative products can be efficiently developed and produced.”2 In this strategy, the platform is the innovation; the rest is execution.

The ubiquitous Swatch watch is an example of a successful product family based on a common platform. The Swatch platform is a small set of timepiece subsystems linked together through a few electronic interfaces. This platform is, in effect, the innovation. Almost every Swatch uses the same platform, which is simple, inexpensive to manufacture, and capable of supporting endless external variations. This platform saved its maker, Société Micromécanique et Horologère (SMH), from business failure and helped it produce watches for fashion-oriented consumers with different tastes.

Product platforms based on design elegance and “manufacturability” give companies low-cost opportunities to customize their products for different market segments; figure 7-2 shows how the platform of common elements can be joined with some unique elements to produce a product (or service) for a particular market segment. Swatch did this by putting its innovative new clockworks inside a long series of uniquely designed band-case-face configurations, producing many “different” watches for different customer segments from a common base. The true innovation was in the clockworks. That innovation was leveraged in the marketplace by means of platform derivatives. Black & Decker did the same back in the early 1970s. In a classic case of platform innovation, Black & Decker very deliberately created a power tool platform—an electric motor and controls—on which it could base dozens of consumer power tools: electric drills, sanders, saws, grinders, and others. Thanks to that common platform and the cost advantage it conferred, Black & Decker was able to gain leadership in many consumer power tool markets. At the same time it was able to reduce complexity in its operations. Instead of having to manufacture and stock unique motors, components, and switches for every one of its many power tools, the company could accomplish its goals using a single assembly program and common set of components. Costs and components were reduced by orders of magnitude.3

Addressing many market segments with a common platform

The SMH and Black & Decker examples are presented to underscore the value—in some cases—of focusing innovative thinking on platforms instead of on single products and services. What product or service platforms does your company use today? Are promising ideas conceived as single products/services or as platforms capable of supporting many different product/service families? If you are not using a platform approach, think of how a single platform could help you reduce costs, increase variety, and address different market segments.

This chapter has described a handful of practical strategies for moving an innovation to the marketplace. Perhaps one will apply to your situation. The total universe of these approaches is limited only by the human imagination. Be aware, however, that one’s range of strategic possibilities is generally limited by practical constraints. For example, as described above, Sony and Apple successfully created new markets and filled key niches with imaginative products, but few business organizations have the creative talent, customer knowledge, financial capital, and technical wherewithal do the same or do so to the same extent. Likewise, a market-entry strategy based on a joint venture assumes that the instigator has something special to offer the venture partner. Not every firm has that.

So consider the strategic moves described here, but think also about your ability to adopt any one of them. What are the constraints on your ability to make a strategic move? What could be done to relax those constraints?

Summing Up

- Gaining and securing a market beachhead—even in a low-end or low-margin segment—can put you in a position to eventually expand into more attractive and profitable segments.

- When barriers to market entry are dauntingly high, avoid a costly direct assault. Instead, try to develop a new and superior process for doing what entrenched rivals are now doing.

- To be successful, product differentiation must be valued by targeted customers. To provide a defensible position, it must also be protected by patents or proprietary methods that make its duplication by rivals difficult or impossible.

- The strategic use of product or service platforms offers a cost-effective way of leveraging an innovation into different market segments.

- Acquisitions and joint ventures offer still other strategic moves for entering or expanding within a market. But beware—they often result in disappointment failure.