3

Recognizing Opportunities

Innovator as Entrepreneur

Key Topics Covered in This Chapter

- A method for recognizing value

- Rough cut business evaluation of opportunities

- Tips for enhancing opportunity recognition

CHAPTER 2 DESCRIBED the many sources of innovative ideas and what management can do to generate them. Ideas are fuel for the innovation process. By themselves, however, they benefit no one. Someone must see in a particular idea its potential for creating value—opportunity recognition. There’s a big difference between an interesting idea and an idea that represents real business or societal value. Can you tell the difference?

Opportunity recognition has been defined by Mark Rice and Gina Colarelli O’Connor as “the match between an unfulfilled market need and a solution that satisfied the need.”1 Recognition triggers the evaluation that moves an idea down the long and often bumpy road toward commercialization. It is a mental process that answers a question every innovator must ask: Does this idea represent real value to anyone? Being able to answer this question correctly is probably as important as having an innovative idea or developing a scientific breakthrough. Some have articulated opportunity recognition in memorable ways. As Thomas Edison told a newspaper reporter after witnessing a demonstration of electric arc lighting, “I have struck a big bonanza.”

The opportunities of most innovations are not always obvious. 3M scientist Art Fry had an idea for which he foresaw a very limited opportunity: using a weak adhesive to make notepaper stick to other things—specifically, as place markers for his church choir’s hymnals. The larger business opportunity for his idea took time to emerge as Post-it notes.

“What can we do with this?” is a question that idea generators must answer; and in some cases the answers are slow in coming, especially when the innovative idea is radical—new to the world and not simply an incremental advance on an existing concept. The technological and market uncertainties that go hand in hand with radical ideas make it difficult for people to see the potential opportunities they contain. DuPont’s developers of Biomax, a biodegradable polymer material, took several years to answer the question. Initially, DuPont researchers thought that thin sheets of their interesting new material could be used as liners for disposable baby diapers. But the diaper manufacturers weren’t interested. After putting the material on the shelf for a long period, someone thought of using it in the banana groves of Central America, where its ability to protect fruit until it reached harvesting age and then disintegrate into a harmless mulch would be a real benefit. But that didn’t prove to be much of a business either. But since then, many applications have been found for this interesting and versatile material.2

Even when an opportunity is recognized, it may be small relative to the innovation’s full potential. This is what happened to the radio early in the twentieth century. Inventor Guiseppe Marconi made great strides in wireless telegraphy, as he called it, in the 1890s. The opportunity he recognized for this development was important but limited: ship-to-shore communication. Governments, shippers, and marine insurers were interested, enough so that Marconi could launch a successful business. And his innovation is credited with saving thousands of lives at sea—seven hundred from the 1912 sinking of the Titanic alone. But the true commercial potential of radiowave transmission eluded Marconi until 1922, when the first wireless transmission of musical entertainment was made. Suddenly, radio was more than a means of sending Morse coded messages between stations. Its potential as a broadcast medium for sharing news and entertainment with the masses was finally recognized.

Marconi’s narrowly conceived opportunity for radio technology is not unique. The Internet, which was initially viewed as a rapid communications medium for the scientific community, followed a similar trajectory. Its utility for the broader public and for business-to-consumer and business-to-business commerce were recognized only later. In this sense, opportunity recognition is often an unfolding process. The initial window of opportunity is a passageway to others.

As Rice and O’Connor have pointed out through a number of examples, opportunity recognition may be necessary at more than one stage of the innovation process. They cite the case of GE’s development of digital X-ray technology, where many instances of opportunity recognition were identified, each at a different phase in the technology’s long journey toward eventual commercialization: “the research scientist (1984); someone from the outside firm (1987); the first head of the business unit (1988); the head of central research (1992); the CEO (1993); and the second head of the business unit (1997).”3 The merits of the project had to be recognized at each point in order to maintain support and funding, and also because the nature of the opportunity itself was not fixed.

A Method for Opportunity Recognition

Recognizing the opportunity associated with an innovation is usually chancy. Data about the innovation’s performance in use is either limited or speculative. How customers will respond to a commercial version of the innovation can only be inferred. As a result, many innovators either fail to recognize opportunities or overestimate them.

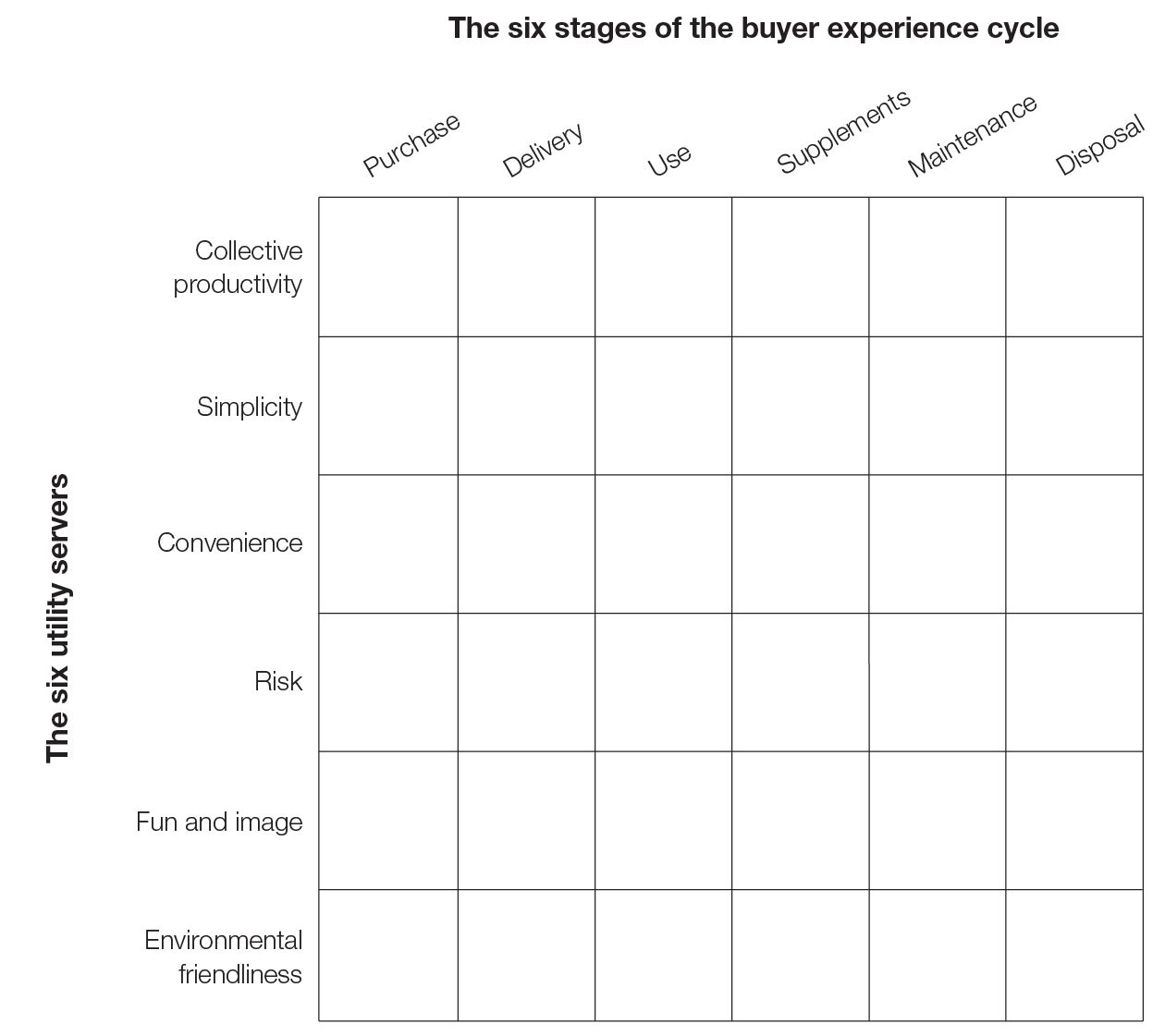

Although there is no proven formula for opportunity recognition, W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne described a method called the buyer utility map that indicates the likelihood that customers will be attracted to a new idea or product.4 Kim and Mauborgne believe in focusing on an innovation’s utility—how it will change the lives or work of customers. The buyer utility map, shown in figure 3-1, helps innovators to think about two things: (1) the levers they can pull in delivering utility to customers, and (2) the various stages in the “buyer experience cycle,” a cycle that runs from purchase through disposal. Each stage encompasses a wide variety of specific experiences. An innovator can use this map to identify the utility offered by the new product or service at various stages of the buyer experience cycle.

The buyer utility map

Source: W. Chan Kim and Reneé Mauborgne, “Knowing a Winning Idea When You See One,” Harvard Business Review, September–October 2000, 129–138.

Kim and Mauborgne offer the example of discount broker Charles Schwab. With 24/7 phone (and later online) service, Schwab created utility in the “convenience-purchase” cell of the matrix. By offering instantaneous trade confirmations over a secure connection it also offered utility in the “risk-purchase” cell.

You can use this utility-buyer experience map to assess the utility an innovative idea. Ask yourself:

- Where can we create the greatest utility for our customers? Does our idea fill this space?

- Is that utility higher or lower than the utility created by existing products or services offered by our competitors?

- Which of these utilities matters most to customers?

- How could we redesign our product/service idea to offer the greatest utility to customers in the areas that matter most to them?

In answering each question, you can get a good sense of the business potential of an innovative idea.

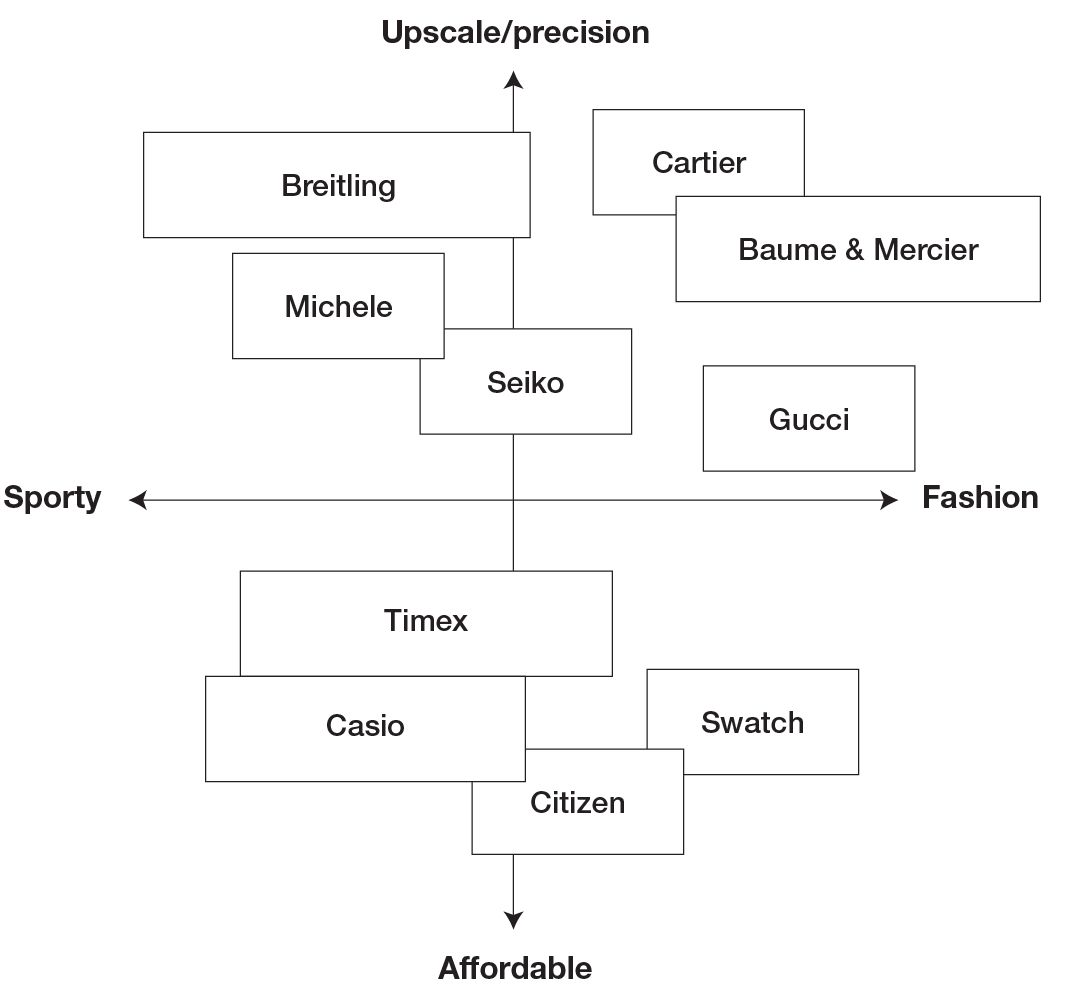

Another approach is perceptual mapping, a market research tool used to compare products or product ideas against the perceptions of customers. A perceptual map is (usually) a two-dimensional space on which alternative product or product ideas are plotted against their attributes or the primary needs of customers. Decision makers then have a graphic image of the “positioning” of their product ideas relative to primary customer needs. For example, figure 3-2 is a perceptual map created for men’s wrist watches. It indicates roughly how customers perceive many of leading brands in terms of two dimensions: sporty versus fashion, and upscale/precision versus affordable. Notice that these dimensions create market segments.

For innovators, and for decision makers who must evaluate their ideas, a perceptual map can be used to locate unserved segments. In figure 3-2, for example, if Casio didn’t exist, the innovator and management would be able to identify an unserved segment in the sporty-affordable quadrant. They would then know how better to direct scarce idea-development resources.

Perception mapping—men’s watches

Rough Cut Business Evaluation

Let’s assume that your innovative idea qualifies as a legitimate opportunity—that is, it has real value for customers. One more task is required before the idea can move forward into development and formal market research: a rough cut business evaluation. A rough cut business evaluation considers three fundamental questions:

- Does the innovation have a strategic fit with your company?

- Do you have the technical competencies to make it work?

- Do you have the business competencies to make it successful?

Note that a rough cut evaluation is qualitative. More complete and quantitative idea screening comes later, as the idea becomes more completely formed. At this point, you simply want to determine if some individual or team should use time and resources to investigate the idea and develop it further. The end point for this type of evaluation should be a formal business plan (see appendix A for a sample business plan).

Strategic Fit

You may have a great idea, but if that idea lacks strategic fit with your company, its development and commercialization could create long-term problems. For example, a new system for making espresso coffee in half the time would not have a strategic fit with discount broker Charles Schwab, but a new and easy-to-use financial planning software program would. That’s obvious, but the strategic fit of ideas floating around your company are bound to be much less obvious, so be very thoughtful as you think through the question of strategic fit.

What should you do with a good idea that lacks strategic fit? A good idea, almost by definition, has profit potential—for someone. But in ill-equipped hands, that potential may never be realized. Also, pushing into unfamiliar terrain with an innovation is risky. Thus, the choices are threefold: either drop the idea, license it to someone who can do something with it, or create a separate or joint venture organization to develop it. Let’s consider the last two.

The motives behind licensing agreements are widely observed. Here’s a classic example. A small pharmaceutical company develops and gains regulatory approval to produce and sell a new drug. But it has neither manufacturing capabilities nor effective distribution networks. It determines that its best option is to license manufacturing and distribution to a major pharmaceutical company in return for an upfront payment and a royalty on sales. Thus the innovator captures value from its invention even though it lacks the capacity to make it commercially successful.

The joint venture operates on the same principle, bringing together complementary resources to capture value. Here, the innovator teams up with an organization that possesses the missing resources, capabilities, or market access. Working together, the two (or more) organizations have a chance of making a success of the recognized opportunity.

Tips for Enhancing Opportunity Recognition

Though opportunity recognition takes place in the minds of individual employees, management can take steps to facilitate it. It can:

- Be very clear about company strategy and long-term objectives: This helps people answer the question, “Does my idea fit with company strategy?” That question cannot be answered if people don’t understand the strategy.

- Expose research scientists and engineers to customers and marketing: This exposure arms the opportunity recognition mechanism within these individuals.

- Give people with ideas a place to take them: In their study of radical innovation, Richard Leifer and his colleagues note that the technical professionals who generate so many breakthrough ideas don’t always have the breadth of experience to recognize the opportunities they represent. They need a place to take their idea—a place where they can ask the question: “What could we do with this?” That “place” is often a business development manager who serves as a link between the company’s R&D efforts and the world of customers and their problems.c

Technical Competencies

Every company has one or more technical competencies. A securities broker-dealer has competencies in trading, market making, and information systems. A mini-mill steel company has technical competencies in metallurgy, manufacturing, and logistics, among others. Does your company have the technical know-how to successfully develop a particular idea? If it does not, could that know-how be acquired?

Business Competencies

Business competencies include marketing, distribution, new-product development, the ability to serve a particular customer base, the ability to manage widely scattered employees and facilities, and so forth. What are your core business competencies? Are they the same ones your innovative idea will need in order to become successful? If your company lacks any of the required competencies, ask yourself if the idea is big enough to justify the effort and expense of developing those competencies.

Summing Up

This chapter has explored the important activity of opportunity recognition, which attempts to answer a fundamental question: Does this idea represent real value to current or potential customers? To help you be successful in this activity, this chapter has considered the following:

- A method for recognizing value: This method is based on Kim and Mauborgne’s buyer utility map, which helps innovators to think about two things: (1) the levers they can pull in delivering utility to customers, and (2) the various stages in the buyer experience cycle, which runs from purchase to disposal.

- Perceptual mapping: Perceptual mapping is a market research tool used to compare products or product ideas against the perceptions of customers. A perceptual map is (usually) a two-dimensional space on which alternative product or product ideas are plotted against their attributes or the primary needs of customers.

- Rough cut business evaluation: This evaluation of opportunities offers another nonquantitative screen that separates good ideas from the rest. It asks three fundamental questions: Does the innovation have a strategic fit with the company? Does the company have the technical competencies to make it work? Does the company have the business competencies to make it successful? If you get positive answers to all three, the idea has potential.

- Tips for enhancing opportunity recognition.

Finally, the chapter suggests several things that management can do to facilitate opportunity recognition among employees.