1

Types of Innovation

Several Types on Many Fronts

Key Topics Covered in This Chapter

- Incremental and radical innovation

- Why incremental innovation dominates

- Innovation in processes and services

THE MEANING OF innovation is revealed by its Latin root, nova, or new. It is generally understood as the introduction of a new thing or method. Here’s a more elaborate definition: innovation is the embodiment, combination, and/or synthesis of knowledge in original, relevant, valued new products, processes, or services.

However you define it, innovation takes a number of forms. This chapter will acquaint you with each and help you see how they can help or challenge your business.

Incremental and Radical Innovation

Innovation scholars generally point to two different types of innovation: incremental and radical. (“Other Terms: Sustaining and Disruptive” below provides another way of looking at the different types of innovation.) Incremental innovation is generally understood to exploit existing forms or technologies. It either improves on something that already exists or reconfigures an existing form or technology to serve some other purpose. In this sense it is innovation at the margins. For example, Intel’s Pentium 4 computer chip represented an incremental innovation over its immediate predecessor, the Pentium 3, since both were based on the same fundamental technology. The Pentium 4 incorporated design improvements and new features that enhanced chip performance. The same can be said for the GPS (global positioning satellite)-based position locators found in many luxury automobiles; these are less innovations than the application of existing GPS technology to a new use (see “Incremental Innovation with a Powerful Twist”).

Other Terms: Sustaining and Disruptive

Though the terms incremental and radical are commonly used to describe the two major forms of innovation, the writing of Harvard professor Clayton Christensen has introduced alternatives and used them in somewhat different ways. Christensen uses the terms sustaining and disruptive to describe innovations. As he writes: “Some sustaining technologies can be discontinuous or radical in characters, while others are of an incremental nature. What all sustaining technologies have in common is that they improve the performance of established products . . . Most technological advances in a given industry are sustaining in character . . . Disruptive technologies bring to a market a very different value proposition than had been available previously.”a

In many instances, the disruptive technologies described by Christensen create new markets. Those markets are initially small, but sometimes grow large.

A radical innovation, in contrast, is something new to the world and a departure from existing technology or methods. The terms breakthrough and discontinuous are often used as synonyms for radical innovation. The transistor technology developed at the Bell Labs represented a radical innovation that undermined the electronics industry’s dominant players, which at the time were deeply committed to vacuum tube technology. The same could be said for jet propulsion during the 1940s, when piston-powered engines dominated aviation. Likewise, the silicon-germanium (SiGe) chip technology developed by IBM in the late 1990s represented a radical innovation. SiGe chips had four times the switching power of conventional silicon chips and could operate with much less power, making them ideal for applications in new generations of cell phones, laptop computers, handheld digital devices, and other small, portable devices.1 Another example of radical innovation is seen in the digital imaging technology used in today’s consumer and professional cameras; this represents a radical departure from the chemically coated film technology on which George Eastman built the Eastman Kodak Corporation and the modern photo industry over a century ago. Because of the rapid diffusion of digital imaging—from specialized applications such as satellite earth imaging to amateur photography—photographic film sales have plummeted.

Incremental Innovation with a Powerful Twist

Earlier, an incremental innovation was defined as one that either improves upon something that already exists or reconfigures an existing form or technology to serve another purpose. Marc Meyer, a professor at Northeastern University, has illuminated the last phrase of that definition in his book, The Fast Path to Corporate Growth.b Using companies such as IBM, Honda, Mars, and The Math Works as examples, Meyer describes how companies can leverage their current know-how and technologies to serve new markets and to create new lines of business. The success of the Apple iPod provides rather compelling evidence of this strategy’s power. By thinking outside the box of its served market, and by using many of its current technological capabilities, Apple created a new and fast-growing business.

A team of researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute defined a radical innovation more specifically as an innovation with one or more of the following characteristics:

- An entirely new set of performance features

- Improvements in known performance features of five times or greater, or

- A 30 percent or greater reduction in cost2

One could add to this list one of the characteristics cited by Lee A. Sage and the PACE awards program for innovation in the auto supply industry: a change in the basis of competition.3

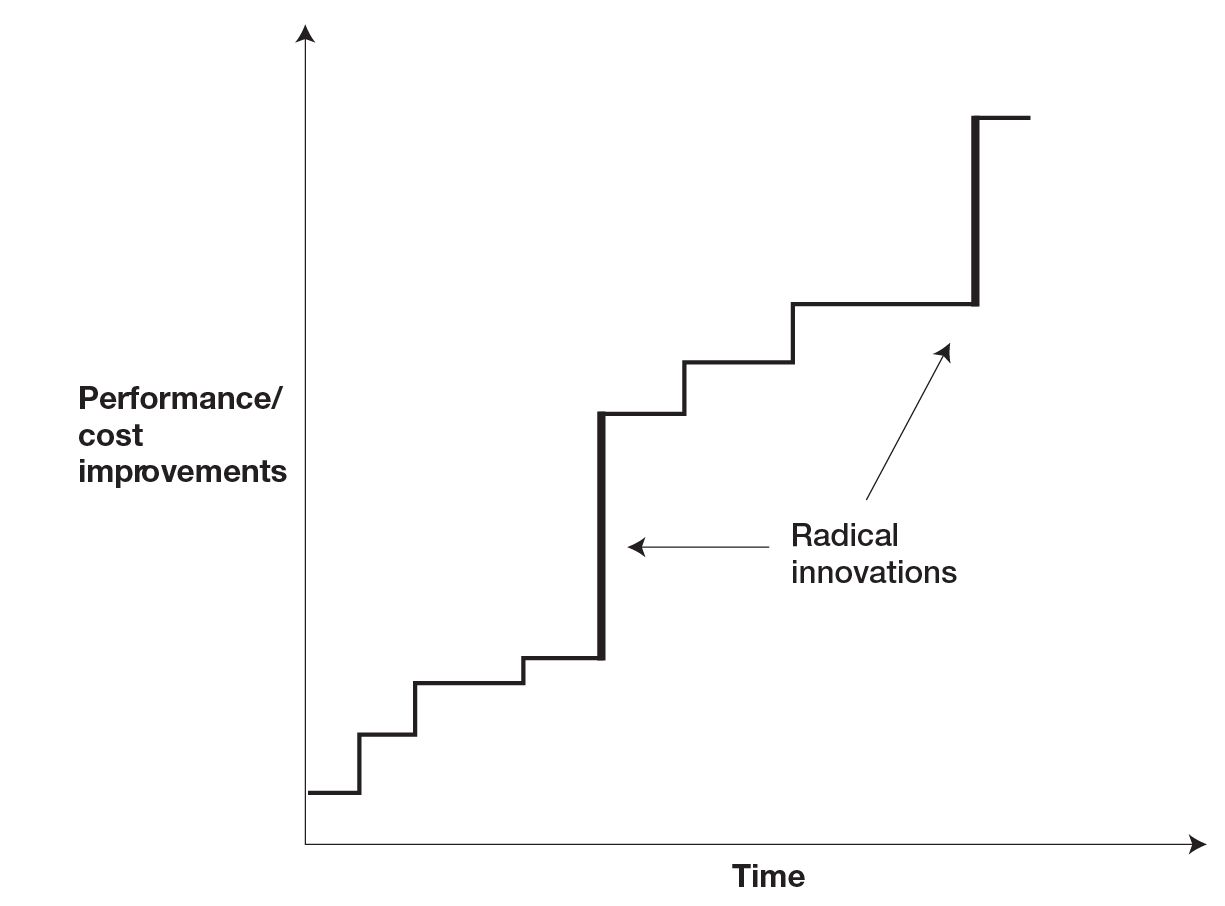

Within industries, incremental and radical innovations go hand in hand. The course of innovation is generally characterized by long periods of incremental innovation punctuated by infrequent radical innovations. For example, in electronics, we observe the introduction of vacuum tubes, which were displaced by transistors, which were in turn largely displaced by the semiconductor. Each of these major transitions represented a great leap forward, but was followed by a period of steady incremental improvements that gradually enhanced performance, lowered cost, and/or reduced size. Figure 1-1 represents a theoretical time line in which radical and incremental improvements take place. Note in this simplified illustration how progress is made through small incremental improvements until radical innovations appear. Progress then takes an abrupt leap forward. Incremental innovation then resumes.

Radical ideas are always in the works somewhere—in R&D labs or in the minds of scientists or entrepreneurs. They usually take a long time to germinate and develop. Their appearance in the marketplace (and few make it to that point) is both infrequent and generally unpredictable. Incremental innovation follows in it train, usually after what Michael Tushman and Charles O’Reilly have called a “period of technological ferment.” They use different technologies for keeping time as an example: “During this period of ferment, competing technological variants, each with different operating principles, vie for market acceptance. The competition occurs between the existing and the new technology (e.g., between tuning forks, quartz, and escapement oscillation in the watch industry) as well as among variants of that new technology.”4

An industry time line of radical and incremental improvement

These periods of ferment are confusing and uncertain for both producers and customers. In the absence of technical standards, producers don’t know which of several new courses to follow (e.g., VHS or Betamax formats; the Mac or DOS/Windows operating systems; HD DVD or Blu-ray). Customers are sometimes paralyzed over the choice of staying with the old technology, switching to the new, or waiting for something even better to come along. Once this period of ferment ends and a dominant technological format emerges, incremental innovation and improvement resumes.

At this point you may find it useful to think about the trajectory of innovation in your own industry. Looking back over the past ten years or so, can you identify innovations that really changed the basis of competition or improved performance in major ways? Which innovations would you describe as radical, and which were clearly incremental? Now look to the present:

- Are you aware of radical innovations now in progress that will impact your industry?

- If and when those innovations enter the marketplace, how will they affect competition?

- How might these innovations impact your own company’s sales and profitability?

Factors That Favor Incremental Innovation

Radical innovations have the potential to change the basis of competition in favor of the innovator. For example, IBM’s introduction of the electric typewriter signaled the end for all manual typewriter makers in the office market and gave IBM a commanding share of that market for decades. Henry Ford’s innovations in automobile design and assembly likewise changed the nature of the emerging auto industry and gave his company a grip on the market that no one would break for over fifteen years. More recently, Wal-Mart’s supply chain innovation gave it a major cost advantage over Sears, J.C. Penney, Kmart, and other retail stores, and helped it gain dominance in mass-market retailing. Indeed, there is evidence that the greatest profits and the greatest source of future competitive power are found in radical innovation.5

Despite the advantage of radical innovation, it presents companies with several serious challenges. Projects dedicated to radical innovation are risky, expensive, and usually take many years to produce tangible results—if they produce them at all. Research by Leifer and his colleagues on eleven radical innovation R&D projects indicated that at least ten years were required to show tangible results.6 To be successful, companies must have the patience, determination, and the budgets to support these long timelines. Management and shareholders must be willing to patiently await the future—and lose plenty of sleep along the way.

Radical innovation’s association with risk, expense, and long time lines encourages most established companies to pursue incremental innovation, which is safer, cheaper, and more likely to produce results within a reasonable time. By one estimate, 85 to 95 percent of corporate R&D portfolios are made up of incremental projects.7

Incremental innovation handled systematically provides business units with the steady streams of new, improved, and varied products and services they need to grow and stay competitive. Incremental innovators must, however, observe two cautions:

- Avoid the “more bells and whistles” syndrome: Pressed by marketers to churn out new versions every few years, many product developers simply add features that few customers really want. This practice irritates many users and creates a future market for true innovators who develop something simpler and more elegant. For example, every new version of office application software suites seems to be bigger, more expensive, and more difficult to master than their predecessors—but offers few tangible benefits for most customers. Customers complain but have few alternatives. Someday, an innovator may provide an alternative that consumes less memory, is competent, less expensive, easier to master, and fully compatible with Microsoft Word, the dominant product. (We may be observing something analogous in the growing success of Linux, which for many is becoming an alternative to the larger, more complex Windows operating system.)

- Don’t put all of your chips on incremental innovation. Yes, investments in incremental innovation are less risky and produce results more quickly. But they seldom create a bridge between current and the future generations of technology. Nor will they alter the competitive game sharply in your favor. Only radical innovation can do that. So find a balance in your pursuit of incremental and radical innovations. (Look for more on finding that balance in chapter 10, where portfolio strategy is discussed.) When a game-changing innovation eventually appears, you want it to be one of your own invention.

Process Innovations

People are used to thinking of innovation in terms of physical, manufactured goods such as computer chips, flat-screen displays, fuel cells, night-vision equipment, and so forth. In reality, process innovations are just as important in the competitive life of companies and in industries as diverse as steel, glass, brewing, chemicals, petroleum refining, and paint making.

In many cases, process innovation lowers unit production costs, often by reducing the number of disconnected process steps. In his study of the plate-glass-making industry, James Utterback has provided an illuminating example of how costs can be lowered when innovators find ways to reduce the number of disconnected process steps.8

Plate glass was traditionally produced through a series of separate steps: mixing and melting the ingredients in a furnace; casting a glass ingot in a mold; annealing the ingot in a special oven; and, finally, grinding and polishing the ingot using successively finer abrasives. This process was slow, labor- and energy-intensive, and very expensive. Over the years, innovators in the glass industry found ways to integrate or mechanize various steps, thus increasing throughput time and reducing unit cost.

The ultimate glassmaking innovation, however, was the “float glass” process introduced by U.K.-based Pilkington Glass in the 1960s. That process, the result of ten years of thinking, experimenting, and debugging, integrated all the tasks of glassmaking into a single automated step. Raw materials poured into a furnace at one end became a continuous ribbon of molten glass that, after passing through an annealing oven, emerged as a flawlessly smooth finished product at the other end. The costly grinding and polishing steps were entirely eliminated. Pilkington’s innovation so reduced the cost of production that the float glass process quickly displaced all other approaches, giving the company a major competitive advantage for many years.

The Product-Process Connection

It’s one thing to create an innovative new product or service; it’s another thing to create a process capable of manufacturing or delivering the new product/service at a price the target market will accept. Thus, innovation in both realms is often connected, and some innovative product ideas must await process innovation before they can achieve market traction.

The product-process connection is nicely illustrated in the case of the now-ubiquitous disposable baby diaper. Versions of this product first appeared in North America in the mid-1950s, during the postwar baby boom, when the market for this product was huge and growing. Nevertheless, these early disposables failed to gain more than a 1 percent market share. The reason was twofold: poor performance and price.

When Cincinnati-based Procter & Gamble entered the field, its R&D people very quickly solved the performance problem by using more suitable materials and a new design. That was the easy part. Developing a cost-effective process for manufacturing its new diaper proved to be a far greater challenge, and one that held back market rollout for longer than anticipated. One engineer described P&G’s quest for an effective diapermaking process as the most complex operation the company had ever faced.9 Their problem was finding a way to manufacture this multipart, multimaterial product in huge quantities at a price acceptable to customers. The company encountered a similar problem years later when it attempted to develop its ersatz potato chip, Pringles. Here again, the product idea was comparatively simple and straightforward; developing an extrusion and baking process that would produce high volumes of very thin, stackable, and uniformly cooked “chips” proved to be the real challenge.

Service Innovations

Service is another area in which innovation plays a key role. Service innovation sometimes produces winning business models. Here are a few notable examples:

- Dell: Dell’s PCs are very good, but they share the same technologies as machines offered by competitors. What originally set this company apart and gave it a competitive edge was not its product, but its innovative strategy of skipping the middleman and selling custom-configured PCs directly to buyers. Later innovations in supply chain management made this strategy fast and effective—and helped to make Dell the world’s most successful PC manufacturer.

- Southwest Airlines: Herb Kelleher and his associates built this popular and profitable business through an innovative value proposition to customers: low fares, frequent service, and fun. Kelleher initially developed his service concept to compete with automobile and bus transportation in the Texas regional market. It succeeded there and was expanded, eventually making Southwest the most profitable airline in the United States.

- Zipcar: This young company has created an alternative to automobile ownership for urban dwellers in more than a dozen U.S. cities, as well as London and Toronto. Its mission is to offer members affordable twenty-four-hour access to vehicles for short-term round-trips. A member who needs a car for an occasional drive to the suburbs or for weekly grocery hauling reserves one on the company Web site, goes to one of the many locations where Zipcars are parked, unlocks the vehicle with a Zipcard, and drives away. Payment is based on time and mileage. By early 2008, the company had over thirty-five hundred vehicles and more than 300,000 subscribers (“Zipsters”).

Thus, innovation is not the sole domain of physical product companies. Many service-driven companies have long and admirable histories of innovation. But not every service innovator succeeds. Consider the fate of Streamline.com, a Boston-based company whose business model aimed to provide cost-effective, high-quality home delivery of groceries, dry cleaning, prepared meals, shoe repair, and many other household items. It was a great concept, and its inventors supported it with Internet connectivity, a fleet of delivery vans, and a state-of-the-art distribution center. But for all its appeal, Steamline went bankrupt. So did Webvan, an even more ambitious enterprise using a similar business model. In both cases, the service idea was appealing, but the process for delivering value to customer doorsteps either failed or proved too costly. One competitor, Peapod, currently a unit of Royal Ahold, has survived and prospered since its founding in 1989. As of 2008 it was providing online grocery shopping services to customers in many U.S. metropolitan areas in partnership with Royal Ahold’s two major American supermarket chains: Stop & Shop and Giant Food.

So if you’ve developed an appealing innovation service concept, your job has only begun. Give as much or more attention to the process and the infrastructure needed to support it. Think carefully about every step that goes into the production and delivery of your service. Then try to think of how each could be improved (incrementally), combined, or replaced entirely (radically) by something better, faster, and less costly.

Summing Up

This chapter began with a working definition of innovation—as the embodiment, combination, and/or synthesis of knowledge in original, relevant, valued new products, processes, or services. It went on to describe the two major categories within which innovations fall: incremental and radical.

- Incremental innovation exploits existing forms or technologies. It either improves something that already exists, making it “new and improved,” or reconfigures an existing form or technology to serve some other purpose. The GPS position locators found in many luxury automobiles is an example of an existing technology adapted to a different purpose.

- A radical innovation was described as something new to the world. Many radical innovations have the potential to displace established technologies (as the transistor did when first introduced into the world of vacuum tubes) or create entirely new markets.

- When compared with radical innovation, incremental innovation takes less time and involves less risk, which explains why managers favor it. Incremental innovation alone, however, cannot assure a company’s future competitiveness.

- Radical and incremental innovations often operate hand in hand. Thus, the introduction of a successful radical innovation is often followed by a period of incremental innovations, which improve its performance or extend its application.

The chapter went on to underscore the importance of process innovations, which are often overlooked.

- Process innovations generally aim to achieve substantial reductions in unit costs of production or service delivery. In many cases this is accomplished by integrating or eliminating separate process steps.

- Product and process innovations often go hand in hand. As demonstrated by the case of the disposable baby diaper; a breakthrough product often fails to gain market acceptance until a low-cost process for manufacturing it at acceptable quality levels is created.

Finally, service innovations, as exemplified by Southwest Airlines, Dell, and Zipcar, were examined. Service innovators are urged to think carefully about the processes that support production and delivery of their services.