12

Working Through Creative Groups

The Power of Numbers

Key Topics Covered in This Chapter

- Characteristics of creative groups

- Handling conflict in groups

- The effect of time pressure on creativity

WHILE CREATIVITY IS sometimes an individual act, many innovations are products of creative groups. The transistor developed by scientists at Bell Labs is just one example. Groups can often achieve greater creative output than individuals working alone because they bring a greater sum of competencies, insights, and energy to the effort.

Characteristics of Creative Groups

In order to reap greater output, groups must have the right composition of thinking styles and technical skills. The “right” composition, in most cases, means a diversity of thinking styles and skills. Diversity has several benefits:

- Individual differences can produce a creative friction that sparks new ideas.

- Diversity of thought and perspective is a safeguard against groupthink—that is, the tendency of individual thought to converge for social reasons around a particular point of view to the exclusion of other views.

- Diversity of thought and skills provides opportunities for ideas to develop. An electrical engineer, for example, may seek a way to solve a technical problem while another engineer with manufacturing or materials experience may enhance the solution by suggesting ways that would make the end product less costly to produce.

Thus managers must consider how work groups are staffed and how they communicate.

A creative group exhibits paradoxical characteristics. It shows tendencies of thought and action that we’d assume to be mutually exclusive or contradictory. For example, to do its best work, a group needs deep knowledge of subjects relevant to the problem it’s trying to solve, and a mastery of the processes involved. At the same time, however, the group needs fresh perspectives that are unencumbered by the prevailing wisdom or established ways of doing things. Often called a “beginner’s mind,” this is the perspective of a newcomer: a person who is curious, even playful, and willing to ask anything—no matter how naive the question may seem—because she doesn’t know what she doesn’t know. Thus, bringing together contradictory characteristics can catalyze new ideas. (See “Signs That Your Group Lacks Diversity” to help you evaluate your team.)

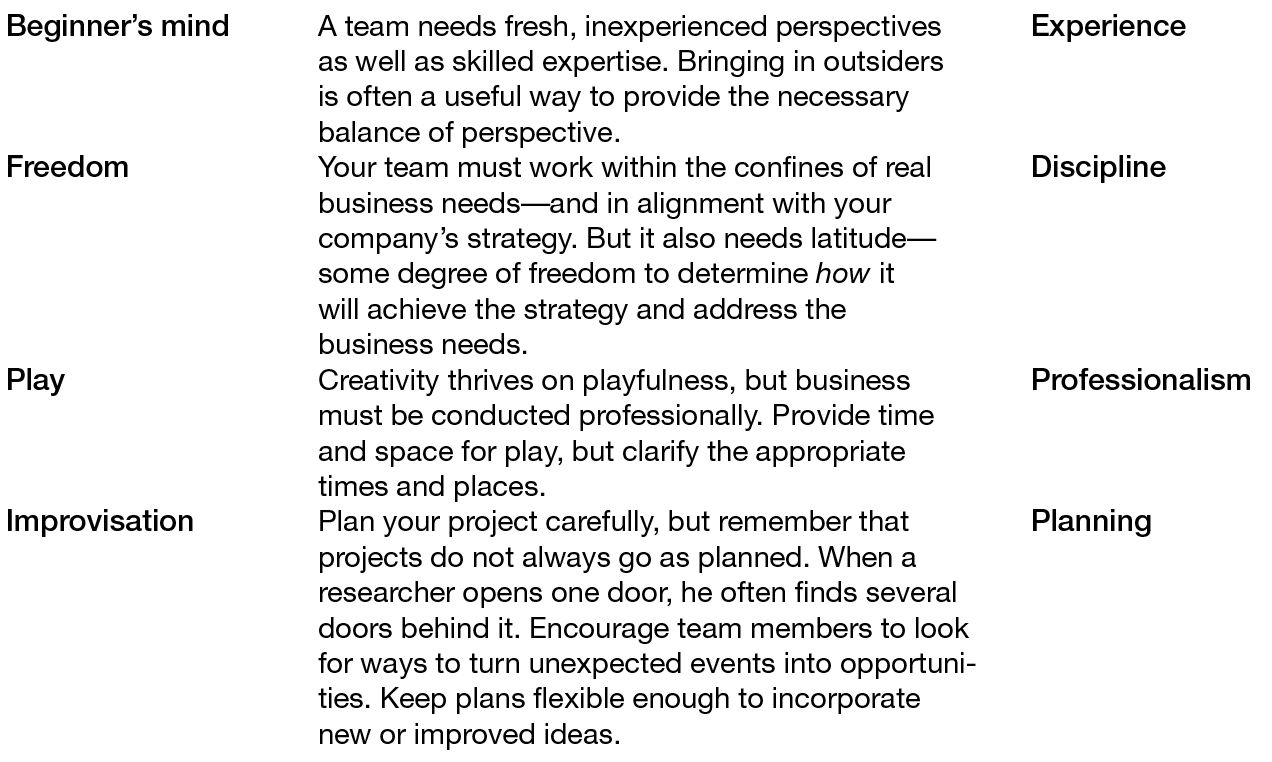

Figure 12-1 describes a number of seemingly contradictory characteristics that a group must have to maximize its creative potential. Many people mistakenly assume that creativity is a function of only the elements in the left column: the beginner‘s mind, freedom, play, and improvisation. But a blend of the left and the right columns is needed. This paradoxical combination is confusing and disturbing to managers who feel a need for order and linear activity. Accepting this paradox is the first step toward success.

Signs That Your Group Lacks Diversity

If you’re a manager, you’ll know that your group lacks the diversity it needs to be its creative best if you observe one or more of the following:

- Members are reluctant to disagree with each other.

- The group has been working together for more than three years without infusions of new people.

- Members converge on plans and solutions very quickly and with little discussion.

- You suspect that minority opinions are not being heard.

- People regularly defer to a single person.

The paradoxical characteristics of creative groups

Source: Harvard ManageMentor® on Managing for Creativity and Innovation. Adapted with permission.

Divergent and Convergent Thinking

Group creativity is also enhanced when both divergent and convergent thinking are at work. These terms were coined by psychologist J. P. Guilford, who conducted substantial research on creativity. In his lexicon, divergent thinking is the ability to find unique and original solutions and to consider problems in terms of multiple solutions—not just one. He viewed divergent thinking as a key component of creativity. Convergent thinking, on the other hand, narrows many possible solutions to one. In other words, thought patterns converge on a single, optimal solution.

The creative process is fueled by divergent thinking—a breaking away from familiar or established ways of seeing and doing. This seems intuitively obvious. If we continually observe an object from the same vantage point and in the same lighting conditions, we are bound to have the same impression of that object. If we change the lighting or the viewing angle, however, our perceptions may change. They will become more complete—more nuanced. For example, if you looked at the full moon through a small telescope, you would see a flat, bright, meteor-pocked surface with a modest number of striking terrain features. Look at it again a week or so later, when the moon’s phase has created contrasts of sunlight and shadow, and you’ll see something very different: rugged mountains, gaping crevices, and deep craters that were barely noticeable before. The different perspective created by light and darkness makes this possible.

Tips for Improving Convergent Thinking

Work groups are often tempted to converge quickly on what appears to be a single best solution and cut off future debate. It’s the team leader or manager’s job to prevent both. Consider these suggestions:

- Insist on an incubation period during which people can experiment with the various options. Some options will seem less promising after people have thought about them for a week or two.

- Appoint an official devil’s advocate to challenge all assumptions associated with the group’s favored options. That person should be respected and seen as objective.

- Ensure that dissent is tolerated and protected and that dissenters have the freedom to voice contrary views, otherwise groupthink may take control of future decisions.

Seeing things from unfamiliar perspectives makes it possible to develop insights and new ideas. But are those insights valuable? That’s what convergent thinking attempts to answer. It helps to channel the results of divergent thinking into concrete products and services. As new ideas generated by divergent thinking are communicated to others, they are evaluated to determine which ideas are genuinely novel and worth pursuing. That’s convergent thinking. Without it, the creative person working alone could easily pursue an idea that eats up time and resources and leads to nothing of value.

In moving from divergent to convergent thinking, a work group makes a transition from what is novel to what is useful. Convergence sets limits, narrows the field of solutions within a set of constraints. How are those constraints determined? The culture, mission, and priorities of the company and project all contribute to the answer. They help rule out options that lie beyond the scope of the project.

Here are some questions your team might ask as it applies convergent thinking to a range of possible solutions:

- Which functions are essential (from the customer’s point of view) and which are only “nice-to-have”?

- What criteria are determined by the company’s values? For example, Fisher-Price groups insist that any toys developed be “Mom-friendly”—since most toys are purchased by mothers.

- What are the cost constraints?

- What are the size or shape constraints?

- Within what time must the project be completed?

- In what ways must the product or service be compatible with existing products or services?

Diverse Thinking Styles

Beyond divergent and convergent thinking, group creativity benefits when its members approach their work with different preferred thinking styles, and when they bring a variety of skills to a common effort. A preferred thinking style is the unconscious way a person looks at and interacts with the world. When faced with a problem or dilemma, a person will usually approach it through a preferred thought style. And although each style has particular advantages, no one style is better than another.

There are a number of different ways of describing how people think and make decisions. For example, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator breaks down thinking preferences into four categories, with two opposite tendencies in each category:

- Extravert-Introvert: Extraverted people look to others as the primary means of processing information. As they get ideas or grapple with problems, they quickly bring them to the attention of others for feedback. Extraverts energize themselves through their communications with others. Introverted people tend to process information internally first before presenting the results to others. They are happiest when they can sit down alone in a quiet place and think things through, weigh pros and cons, and so forth.

- Sensing-Intuitive: Sensing people tend to prefer hard data, concrete facts—information that is closely tied to the five senses. Intuitive people are more comfortable with ideas and concepts, with the “big picture.”

- Thinking-Feeling: Thinking people prefer logical processes and orderly ways of approaching problems. Feeling people are more attuned to emotional cues; they are more likely to make decisions based on the values or relationships involved.

- Judging-Perceiving: Judging people tend to prefer closure—they like having all the loose ends tied up. By contrast, perceiving people like things more open; they tend to be more comfortable with ambiguity and often want to collect still more data before reaching a decision.

Don’t get hung up on the actual word used to describe any of these styles. Everyone exhibits some aspect of all eight, but they do it in varying degrees. For example, it’s not that a feeling person is incapable of logical thought; rather, it’s that his thinking about a decision tends to be more guided by the emotional impact of that decision on key relationships.

Well-balanced work groups include representatives of these different preferred thinking styles. How well-balanced are your work groups?

Diversity of Skills

Once you’ve assessed how the thinking styles of your group members complement (or duplicate) each other, you’ll have a pretty good feel for whether any gaps exist. It is then time to survey the skills represented on the team. If the team lacks vital technical skills or expertise, it will have trouble developing the ideas it generates. For example, when Thomas Edison began thinking about producing the incandescent electric lamp, he knew that he would have to do lots of experimenting with designs and materials. So he created a team that included technicians with machining, laboratory, and glass-blowing skills. Their skills made it possible for Edison to test hundreds of filament materials in rapid succession. Eventually, a vacuum bulb containing a carbonized cotton filament proved serviceable. But more experiments with materials were needed before his idea could be commercialized. Again, the technical skill set he assembled made it possible to quickly perfect his “electric lamp” to the point where it would be commercialized.

In some cases, you may have to look outside your company—or industry—to find the technical know-how you need. For example, when engineers at a ceramics manufacturer experienced problems with getting ceramics to release from their molds, they realized that their problem had to do with quick-freezing—not with ceramics. So instead of seeking out other ceramics experts, they turned to food industry experts, who had special knowledge of quick-freezing.

Generally, you know that it’s time to look outward for solutions when a group has been working for a long time on a problem without success. The same applies when team members always agree or always disagree on what should be done.

Tips for Filling Team Gaps

As you seek skills/knowledge diversification:

- Look for people whose intellectual perspectives complement—but don’t duplicate—your own preferred styles and skills, and those of your group.

- Look for a balance of expertise and personal characteristics (such as initiative, ability to get along with others, etc.) in each new hire.

- Look for people who can work across functional boundaries.

- When you specify hiring criteria, put a premium on finding the skills that the group currently lacks. Don’t simply list a standard set of skills.

- Explore nontraditional hiring channels—that is, channels other than those used by your company’s human resources department.

- Consider adding a customer or outside professional to the group. Either will bring a much different perspective. Xerox engineers, for example brought in anthropologists to help them design more user-friendly copiers.

Remember too that if your goal is to create change within the group, hiring one person who has a different perspective is insufficient. A lone hire with a different outlook many soon feel isolated and ineffective. For different thinking styles to make a difference, two things must happen: you must hire a critical mass of these people, and those people must be thoroughly integrated into the team.

Conflict in Groups—and How to Handle It

Although diversity of thinking and skills is valuable, it’s not without hazards. Different thinking styles do not produce unbroken harmony—you would not want it in any case. Expect disagreement and clashes. The manager’s job is to make conflict positive and creative.

For creative conflict to work, group members must listen to each other, be willing to understand different viewpoints, and question each other’s assumptions. At the same time, managers must prevent that conflict from becoming personal or from going underground where resentment can simmer. The best antidote to destructive conflict is a set of group norms for dealing with it. What should your group’s operating norms be? Here are a few examples. You might call them the “Group Code of Conduct.”

- Every group member should show respect to others.

- Every member should make a commitment to active listening.

- Everyone has a right to disagree and an obligation to challenge others’ assumptions.

- Everyone shall have an opportunity to speak.

- Conflicting views are an important source of learning.

- Ideas and assumptions may be attacked but individuals may not.

- Calculated risk taking is good.

- Failures should be acknowledged and examined for their lessons.

- Playful attitudes are welcomed.

- Successes will be celebrated as a group.

Whatever norms your group adopts, make sure that all members have a hand in creating them—and that everyone is willing to abide by them.

Three Steps for Handling Creative Conflict

Even with consensus on norms of behavior, conflict is a fact of life in groups. The following three steps will help you turn that conflict into a creative asset.

- Create a climate that makes people willing to discuss difficult issues: Help your team understand the concept of “the moose on the table” (the big issue or problem that is impeding progress but which no one wants to discuss). Make it clear that you want the tough issues aired, and that anyone can point out a moose.

- Facilitate the discussion: How do you deal with a moose once it has been identified? Use the following guidelines:

- First, acknowledge the issue, even if only one person sees it.

- Refer back to group norms on how people have agreed to treat each other.

- Encourage the person who identified the moose to be specific.

- Keep all discussion impersonal. The point is not to assign blame—discuss what is impeding progress, not who.

If the issue involves someone’s behavior, encourage the person who identified the problem to explain how the behavior affects him or her, rather than make assumptions about the motivation behind the behavior. For example, if someone is not completing work when promised, you might say, “When your work is not completed on time, the group is unable to meet deadlines,” not, “I know you are not really excited about this product.”

If someone is not providing necessary leadership, you might say, “When you don’t provide us with direction, we spend a lot of time trying to second-guess you, and that makes us unproductive,” not, “You don’t seem to have any idea what we should be doing on this project.”

- Move toward closure by discussing what can be done: Leave with some concrete suggestions for improvement, if not a solution to the problem.

If the subject is too sensitive and discussions are going nowhere, consider adjourning your meeting until a specified later date so that people can cool down. Or consider bringing in a facilitator.

Time Pressure and Group Creativity

Time is one of the things that every creative individual and creative group must have to achieve anything worthwhile. Radical innovations, as we’ve seen, often take ten or more years to emerge from the idea factories of research scientists. Incremental innovation of complex products such as new aircraft and new passenger cars often requires three to five years of development. Given these observations, how much time do creative people need? How much time should managers give them? These are important questions for managers as they attempt to meet organizational goals with limited resources.

Academics have studied the time pressure–creativity connection for a long time. In general, these studies point to a curvilinear relationship between the two—that is, to a certain point, pressure helps. But beyond that point, pressure has a negative impact. Teresa Amabile, Constance Hadley, and Steven Kramer continued that research, reaching some eye-opening conclusions. They point to instances where ingenuity flourishes under extreme time pressure—just as managers have always believed (or hoped!). They point, for example, to a NASA team that within hours came up with a crude but effective fix for the air filtration system aboard Apollo 13—a creative solution that saved the mission and its crew. On the other hand, they point to the Bell Labs teams that felt no such pressure; that team, nevertheless, created the transistor and the laser, which open the door to a cornucopia of innovative products.

After studying over nine thousand daily diary entries of people engaged in projects demanding high levels of creativity, Amabile and her coauthors concluded that time pressure usually kills creativity: “Our study indicates that the more time pressure people feel on a given day, the less likely they will be to think creatively.”1

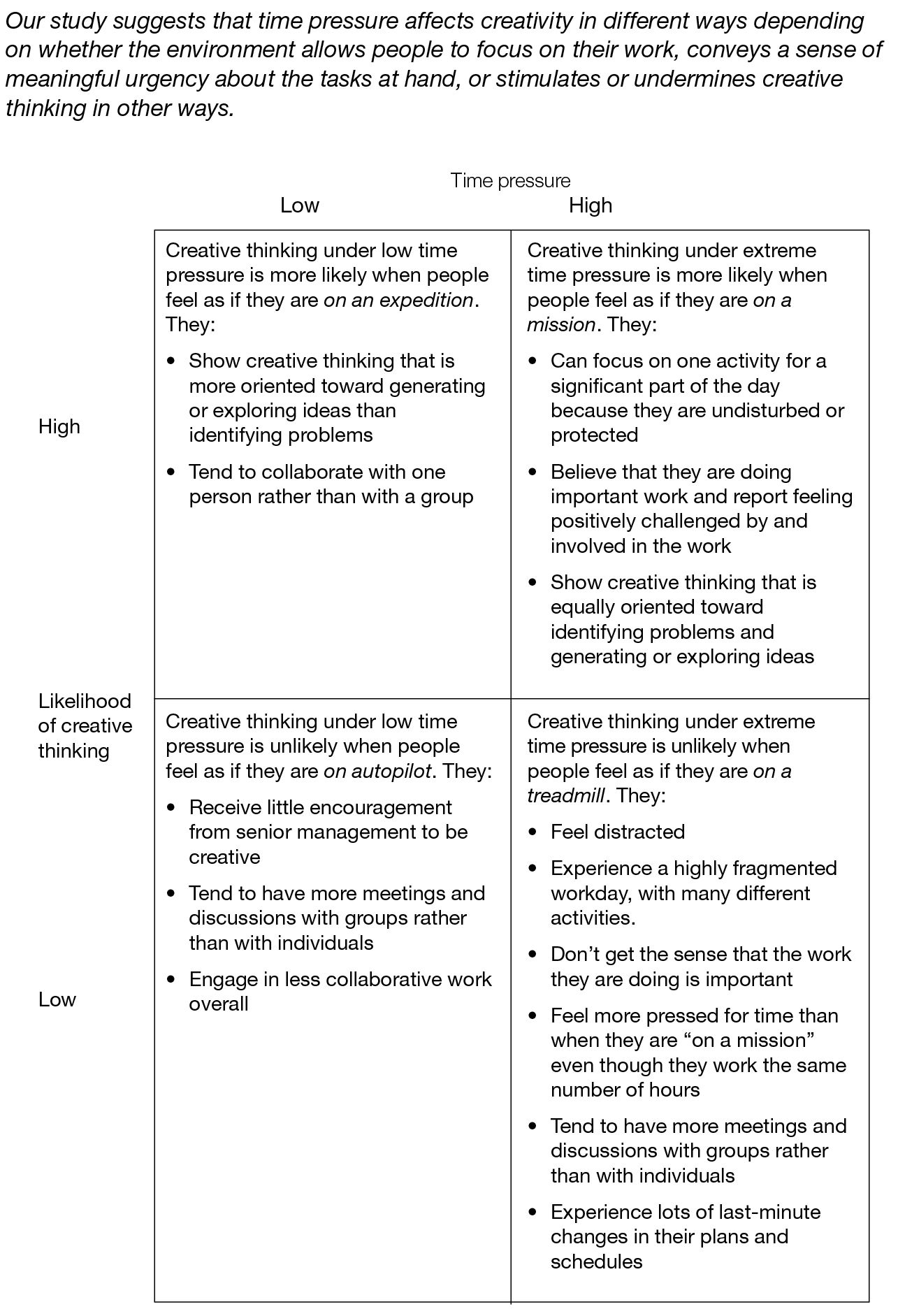

That’s bad news for companies and managers, but not entirely bad. These researchers noted that time pressure affects creativity in different ways depending on whether the environment allows people to focus on their work, conveys a sense of meaningful urgency about their tasks, or stimulates or undermines creativity in other ways. For example, time pressure is not a creativity killer when people feel that they are on a mission, which is what the NASA crew undoubtedly felt.

To help managers understand when and how time pressure affects creativity, we’ve shown the four-quadrant matrix developed by Amabile and her associates in figure 12-2.

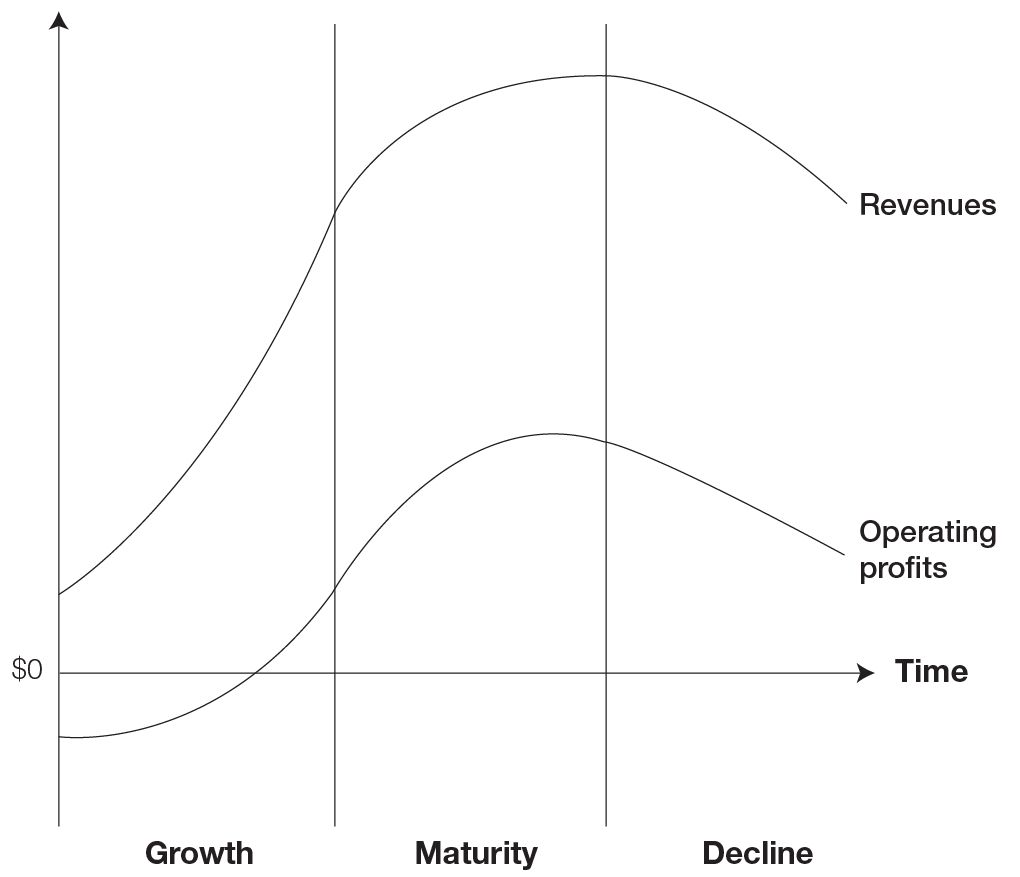

Finding the Right Balance in Group Tenure

If your job is to manage a team or work group that aims to innovate, one of the many things you should pay attention to is the length of time that group members have worked together, or group tenure. Years of working together doesn’t always produce the creativity you’d expect. Beyond a certain point, the opposite is more likely. In this regard, work groups are similar to organizations and products, which have life cycles stages. Those stages are generally associated with one level of vitality or another. Consider the typical product life cycle shown in figure 12-3. Here we see what usually happens with a successful product. Upon introduction it picks up steam on the sales front (the growth stage). Eventually, growth tapers off (the maturity stage), and at some point sales go into decline. Research by Ralph Katz and Tom Allen indicates that R&D groups pass through a similar set of stages if no actions are taken to prevent it. As Katz described their findings: “[G]roup members interacting over a long time are likely to develop standard work patterns that are both familiar and comfortable, patterns in which routine and precedent play relatively large parts—perhaps at the expense of unbiased thought and new ideas.”2

Katz and Allen found that individuals who enter these groups pass through stages of varying innovation productivity. On entering an R&D group, individuals first undergo a period of socialization, during which they spend as much time trying to understand group norms, their bosses’ expectations, and so forth as they spend on innovative work.

The time pressure/creativity matrix

Source: Teresa M. Amabile, Constance N. Hadley, and Steven J. Kramer, “Creativity Under the Gun,” Harvard Business Review, August 2002, 56.

Typical product life cycle

The socialization stage is followed by an innovation period during which they are generally most productive. Individuals in this stage understand the norms of the group and where they fit in, and can concentrate on creative, innovative pursuits. After a while, however, individual group members enter a less-productive period of stabilization. As Katz says, “Employees who continue to work in the same overall job situation for long periods gradually adapt to such steadfast employment by becoming increasingly indifferent to the challenging aspects of their assignments.” Like most other corporate employees, these stabilized R&D workers are less absorbed with the challenges of their work and more absorbed with matters of compensation, benefits, vacations, workplace relationships, and issues with their superiors. “With stability,” Katz writes, “comes a greater loyalty to precedent, to the established patterns of behavior... employees become increasingly content with customary ways of doing things” and so forth.3 Further study indicated that tenure in the group, not chronological age, had the greatest influence on creative productivity.

What solution is available to managers? Ideally, they should try to keep people in the productive innovative period, but how can that be done? Periodically rotating people into other assignments, a commonplace refresher practice, may not be a good solution, as it puts the employee back into the relatively unproductive socialization period. The solution, according to Katz, lies with group managers and how they supervise. He found that managers of high-performing long-tenured groups were:

- Highly respected for their technical accomplishments

- Were not practitioners of participative management, but were more directive

- Set demanding goals

- Challenged people to work in new ways

- Had strong bases of support with senior management

Does your group have this type of leadership?

Summing Up

This chapter addressed the subject of creativity in individual and teams. Organizations have found that innovation is generally a function of collaboration between individuals working within groups. With that in mind, the chapter identified the characteristics of creative groups. Groups must have the right composition of thinking styles and technical skills. The “right” composition, in most cases, means a diversity of thinking styles and skills. It also means bring together some paradoxical characteristics:

- The “beginner’s mind” and experience

- Freedom and discipline

- Pay and professionalism

- Improvisation and planning

Group creativity is also enhanced when both divergent and convergent thinking are at work:

- Divergent thinking is a breaking away from familiar or established ways.

- Convergent thinking attempts to find the value of creative insights.

The chapter also examined the issue of time pressure, which affects both individual and group creativity. Is time pressure a good thing or bad thing? Much research has been done on this issue, and the latest indicates that pressure affects creativity in different ways, depending on whether the environment allows people to focus on their work, conveys a sense of meaningful urgency about their tasks, or stimulates or undermines creativity in other ways.

Finally, the chapter noted the importance of work group tenure, and how you can keep a group from getting stale. The answer, according to two authors, was determined by management style.