2

Idea Generation

Innovation’s Starting Point

Key Topics Covered in This Chapter

- New knowledge as a source of innovation

- Tapping the ideas of customers

- Learning from lead users

- Empathetic design

- Invention factories and skunkworks

- Open market innovation

- The role of mental preparation

- How management can encourage idea generation

- Idea-generating techniques

INNOVATIVE IDEAS HAVE many sources. Some originate in a flash of inspiration. Others are accidental. But as Peter Drucker told readers of Harvard Business Review almost two decades ago, most result from a conscious, purposeful search for opportunities to solve problems or please customers.1 His observation supports Thomas Edison’s famous statement that invention is 1 percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration.

Ideas are essential building blocks from which innovation and innovative technologies and products are made. By one estimate, it takes three thousand of them to produce a single commercial success. 2 Given that ratio, companies must regularly generate many ideas.

This chapter examines six sources of innovative ideas: new knowledge, customers, lead users, empathetic design, invention factories and skunkworks, and the open market of idea. It goes on to discuss the important role of mental preparation, and what management can do to generate more good ideas.

New Knowledge

Many, if not most, radical innovations are the product of new knowledge. Consider the computer, the product of new knowledge in the areas of binary mathematics, symbolic logic, programming concepts, and various technological breakthroughs, including the audion electronic switch. New knowledge developed by Francis Crick and James Watson in the early 1950s on the structure of the DNA molecule opened the door to innovations in medicine, agriculture, and animal husbandry. Likewise, IBM’s innovative silicon-germanium chip resulted from laboratory findings that contradicted accepted wisdom on certain properties of that alloy. The SiGe chip has now found important new uses in electronic devices where processing speed and low power consumption are critically important.

Corning, Inc., whose roots go back to the late nineteenth century, provides one of the best examples of a company that has survived and prospered on market applications developed from new knowledge, most of it generated within its own laboratories. Citing a series of landmark innovations in materials—glass lightbulbs, heat-resistant Pyrex glass, television tubes, extruded honeycomb ceramics for catalytic converters, and fiber optics—Corning Research Fellow George Beall told an audience of industrial R&D members that “the development of landmark new products at Corning has been almost always dependent on knowledge gleaned from previous exploratory research.”3

While innovations based on new knowledge are often powerful, there is generally a lengthy time delay between development of new knowledge and its transformation into commercially viable products and services. The computer took over fifty years to surface in the market. Satellite communications took even longer. Considering all the elements that are required to launch and maintain earth satellites—knowledge of calculus, physics, electronics, and aeronautical science—we can say that the timeline of satellite communications stretches back several hundred years to Newton and Kepler.

Despite the time lags involved with knowledge-based innovation, the rewards are often enormous. Consider Corning’s development of fiber optics technology, which that company now dominates. Corning scientists began learning about the light-transmitting properties of glass “light pipes” in 1966, but it wasn’t until 1970 that a team of company scientists produced a material capable of transmitting electronic impulses at the levels required by standards of the day. It took many more years for the new material to find a place in the market.

Customer Ideas

Customers are an evergreen source of innovative ideas if salespeople, service personnel, market researchers, and R&D workers listen to what customers say and probe for more. Customers, for example are often the best source of information on the weaknesses of current products: “It’s a great device, and I’d use it more often if it would fit in my briefcase.” (Idea: Make a smaller version of the device).

Customers can also be the best source for identifying unsolved problems: “Our pizza restaurant chain has never been able to generate much lunchtime business. It takes too long to prepare and bake a regular pizza.” (Idea 1: Develop an oven capable of cutting the cooking time in half; idea 2: Develop a half-prepared pizza product.)

Most companies appreciate the importance of customers as a source of new ideas, and they mine that source regularly through market research. You should also. When quizzing customers, however, be less concerned with product or service specifications and more concerned with the outcomes that customers seek. This is the advice of consultant Anthony Ulwick, founder of Strategyn. Using the example of music storage media, the preferred outcomes would be “access to a large number of songs, play without distortion over time, resist damage during normal use, and require minimal storage space. These are outcomes, not solutions.”4 The next step, according to Ulwick, is to prioritize the list of desired outcomes according to their importance to customers, with each outcome being quantified. For example, research might indicate that “play without distortion” is the most important value, and “resist damage” is the least important.

Direct Customer Participation

Companies have typically depended on formal market research, focus groups, and routine contacts through sales personnel to tap the ideas of customers. Today, some companies are actively inviting customers to share their ideas via the Internet, producing what some call the “democratization” of innovation. Consider the case of Starbucks. Disappointing business results in late 2007 and early 2008 motivated this company to scramble for ways to regenerate growth. One response was “My Starbucks Idea,” which invites customers to share their ideas for improving Starbucks’s products, the customer experience, and the corporation’s community involvement. In this program, customers describe their ideas via the company Web site. Other customers have an opportunity to vote on the merits on those ideas and leave written comments. Those votes and comments are viewable by all site visitors. The company also tells visitors how it is responding to the most popular ideas.

Consider the following example from the My Starbucks Idea program, as described on its Web site. In late March 2008, a customer offered this suggestion: “Develop a means whereby someone can purchase a gift Starbucks drink for a friend or coworker via the Internet. The company would then send an e-mail to the gift recipient with a message (‘Katie has bought you a drink!’) and a printable bar-coded certificate redeemable at any Starbucks coffee shop.”

Within ten weeks, according to the Starbucks site, sixteen hundred people had voted in favor of this idea and 104 had submitted written comments on why it was a good or bad idea, how the idea could be improved, and so forth.

The Starbucks program garnered more than sixteen thousand ideas from customers within the first few months of operation. During that time, several customer ideas were implemented (e.g., the Starbucks Energy Drink), and a great many more were under review by management. The potential of this type of democratized idea generation is substantial, and the ability of customers to vote on the merits of submitted ideas provides an inexpensive measure of market testing. Best of all, this method is ongoing, costs very little to implement and maintain, and no doubt builds some level of customer identification with the company, its products, and its well-being.

SAS, one of the world’s most successful software companies, likewise taps into its customer base to gather ideas. Every day it gathers—and acts on—customer complaints and suggestions obtained through its Web site, over the telephone, and through an annual user conference. Customer input is prioritized and routed to appropriate SAS experts for evaluation and action. The company estimates that 80 percent of customer requests are acted on. (“Google’s $10 Million Contest” profiles another company that tapped customers for innovative ideas.)

Google’s $10 Million Contest

Like Starbucks, Google has turned to the public for ideas. In 2007, the company announced its plan to develop a mobile phone capable of challenging the Apple iPhone and other contenders. The plan is to base the new device on the “Android” software platform and operating system. This open system allows allied developers to contribute. Some thirty-four companies were involved in the alliance in 2007.

Eager to tap the creativity of the software development community, Google announced the Android Developer Challenge in November 2007, and offered $10 million in prize money to encourage participation. Under the terms of the challenge, submitters of the fifty most promising applications would each be given $25,000 to continue development. Those fifty projects would be reduced to twenty at a later date, and those survivors would receive even higher payments to continue development.

To cash-rich Google, the Android Developer Challenge was an inexpensive technique to quickly attract independent ideas for creating what might become a multibillion-dollar new business.

Beware the Tyranny of Served Markets

Observe one caution in listening to customers: they are capable of diverting you from your pursuit of real innovation. If that sounds counterintuitive, consider this. Good businesspeople take the virtue of listening to customers and pleasing them as an article of faith. But sticking too closely to current customers can stifle innovation and lock your company into technologies that have no future. This happens when (1) customers fail to understand technical possibilities, and (2) when they are afraid that real innovations will render their current systems obsolete. Consider these related examples:

- Market researchers ask a customer focus group to describe the kind of automobile they would like to purchase five years in the future. With limited knowledge of alternative technical possibilities, and with current autos as their only reference point, the focus group describes a vehicle very similar to those currently in the showrooms.

- A customer has recently purchased a $10 million hardware and software system from your company. When queried about new ideas, this customer does not encourage you to create anything that might undermine the value of that investment—such as a new operating system. Instead, you’ll be encouraged to incrementally improve the current system.

Some companies compound the “tyranny of served markets” described in the second example by creating review systems that kill ideas and products that their current customers do not want. They focus all their resources on serving today’s profitable customers and markets. This almost guarantees that they will produce nothing but slightly improved versions of their current products and services and will surely miss the next big wave of change that alters the competitive environment.

Learning from Lead Users

Lead users are another valuable source of potentially innovative ideas. Some studies show that between 10 percent and 40 percent of product users modify off-the-shelf products or develop others that fill their particular needs. Lead users are companies and individuals—both customers and noncustomers—whose needs are far ahead of market trends. They may be pioneering radiologists searching for better ways to produce diagnostic images. They may be military pilots, professional athletes, or mining engineers who modify off-the-shelf equipment to achieve higher effectiveness in the field. In all cases, their needs motivate them to produce innovations that suit their unique requirements—long before manufacturers think of them.

Lead users are seldom interested in commercializing their innovations. Instead, they innovate for their own purposes because existing products fail to meet their needs. And a surprising number of them will freely reveal the nature of their innovations to others. Open source software is an example of the willingness of user-innovators to share their advances. Those innovations can often be adapted to the needs of larger markets.

MIT professor Eric Von Hippel was the first to study lead users as a source of innovative ideas. In several of the fields he studied—notably scientific instruments, semiconductors, and computers—more than half of all innovations were made by users, not by product manufacturers. Thus, approaching these lead users and studying their unique applications and product modifications can effectively augment internal idea generation. As an example, Von Hippel suggests that an automotive brake manufacturer might seek out particular users whose requirements for effective breaking exceed those of normal users. These might be auto racing teams, producers of military aircraft, or manufacturers of heavy trucks.

In most cases, the discovery of a user innovation by a manufacturer is accidental—for example, the result of a field sales representative’s visit to a customer site. More systematic exploitation of user-generated innovation can produce much better results. Von Hippel cites research showing that 3M’s forecasted annual sales of lead user–generated ideas were conservatively estimated to be more than eight times those forecasted for new products developed in the usual 3M manner (see “A Four-Phase Process”). More important, lead user–generated projects were found to create ideas for new product lines, while traditional market-research methods were more likely to produce incremental improvements to existing lines of business.5

A Four-Phase Process

An article coauthored by Eric Von Hippel, Stefan Thomke, and Mary Sonnack described a four-phase process used by some 3M units to glean innovative ideas from lead users. This may work for you.

- Lay the foundation: Identify the targeted markets and the type and level of innovations desired by the organization’s key stakeholders. These stakeholders must be on board early.

- Determine the trends: Talk to experts in the field about what they see as the important trends. These experts are people who have a broad view of emerging technologies and leading-edge application in the area being studied.

- Identify and learn from the lead users: Use networking to identify users at the leading edge of the target market and related markets. Develop relationships with these lead users and gather information from them that points to breakthrough products. Use this learning to shape preliminary product ideas and assess their business potential.

- Develop breakthroughs: The goal of this phase is to move preliminary concepts toward completion. Host two- to three-day workshops with several lead users, a small group of in-house marketing and technical people, and the lead user investigative team. Work in small groups, then as a whole, to design final concepts.

SOURCE: Adapted from Eric Von Hippel, Stefan Thomke, and Mary Sonnack, “Creating Breakthroughs at 3M,” Harvard Business Review, September–October 1999, 47–57.

Empathetic Design

As noted earlier, one of the problems that innovators face in determining market needs is that target customers cannot always recognize or articulate their future needs. Because most are unaware of technical possibilities, they tend to identify their needs in terms of current products and services with which they are already familiar. They express their needs in terms of incremental improvements to these products and services: a thinner laptop, an automobile with better fuel economy, a TV screen with better resolution, faster service. To generate innovations that go beyond incremental improvements, you must identify needs and solve problems that customers may not yet recognize. Empathetic design is a technique for doing this. Empathetic design is an idea-generating technique whereby innovators observe how people use existing products and services in their own environments. Harley-Davidson has used this technique, sending engineers, marketing personnel, and even social anthropologists to HOG (Harley Owners Group) events. These employees observed how Harley owners use and customize their bikes, the problems they encounter using Harley products, and so forth. The company has taken this ethnography approach a step further by sponsoring periodic “Posse Rides” that bring company managers and Harley owners together in 2,300-mile road trips from South Padre Island, Texas, to the Canadian border. These long treks give company participants opportunities to build relationships with customers in a relaxed setting and to observe their likes, dislikes, and biking aspirations.6 Those observations became the raw materials for innovative ideas. Following this same strategy, a Japanese consumer electronics company sent a young engineer to live with an American family for six months to observe how they cooked their meals, communicated with friends, and entertained themselves. Those observations were used in the design of new consumer products.

Some companies take this approach very seriously. IDEO, a leading product design company, bases its design process on an anthropologic approach. Its cofounder, David Kelley, has described some of the things he looks for when he makes a deep dive into the customer world—what people care about, what frustrates them in using current products or services. He watches for smiles or frowns.7

Author/professor Marc Meyer has described how Honda used this same approach in the design of its popular Element SUV. Initially conceived to address the mobility needs of a demographic group for which the company had no uniquely designed vehicle (eighteen- to twenty-six-year-old U.S. males), members of the development team went to college fraternity houses to talk with young men about their transportation-related activities—going to beach, hauling bikes and surfboards to outings, moving furniture between apartments, socializing, etc. They even brought together design team members, a small focus group, and several Honda executives for a weekend campout on a California beach. Through these and other avenues of inquiry, the development team learned that their young male target market needed a spacious interior for stowing gear, large back and side doors for getting gear and people in and out, and, of course, a powerful sound system. They also needed a cargo-area floor that was flat and easy to sweep out, and scratchresistant exterior body panels. Models and sketches developed by the design team were shared with “the guys” to obtain feedback.

The resulting vehicle incorporated features that accommodated the lifestyles of eighteen- to twenty-six-year-old men at a reasonable price. First-year sales of the Element were twice what Honda had anticipated. To the company’s delight, many buyers were men and women in their thirties, forties, and fifties who shared one thing with the initial target audience: an active lifestyle.8

Procter & Gamble, a prolific new-product producer, is another user of empathetic design. It trains all new R&D personnel in what it calls “Product Research,” P&G’s approach to observing how customers use products in their day-to-day lives. The program’s goal is to put people who have knowledge of technical possibilities and design in direct contact with the world experienced by potential customers. As described by Dorothy Leonard and Jeffrey Rayport, empathetic design is a five-step process:9

- Observe: As described above, company representatives observe people using products in their home and workplaces. The key questions in this step are: who should be observed, and who should do the observing?

- Capture data: Observers should capture data on what people are doing, why they are doing it, and the problems they encounter. Since much of the data is visual and nonquantifiable, use photographs, videos, and drawings to capture the data.

- Reflection and analysis: In this step, observers return from the field and share their experiences with colleagues. Reflection and analysis may result in returning people to the field to gather more data.

- Brainstorm: This step is used to transform observations into graphic representations of possible solutions.

- Develop solution prototypes: Prototypes clarify new concepts, allow others to interact with them, and can be used to stimulate the reactions of potential customers. Are potential customers attracted by the prototypes? What alterations do they suggest?

As the reader can easily imagine, empathetic design is especially important when developing consumer products for nondomestic markets, where preferences for product size, colors, and applications may be very different than those preferred by the home market.

Invention Factories and Skunkworks

Many large manufacturers generate and develop innovative ideas through formal research and development (R&D) units—innovation factories, if you will (“The Wizard’s Invention Factory” discusses the granddaddy of them all). Some enterprises support R&D at two levels: the corporate level and the business-unit level. Generally, corporate-level R&D works on radical innovations and enabling technologies that various operating units can use. Bell Labs, a research arm of Alcatel-Lucent, provides an example. Since its founding in 1925 as an R&D center for Bell Telephone, Bell Labs has produced a stream of scientific and technological breakthroughs, including sound-synchronous motion pictures, the transistor, longdistance television transmission, digital cell phone technology, the wireless local area network, and the Unix computer operating system. Our world would be notably different absent innovations spawned in this invention factory, which has a twofold mission:

- Conduct basic research in scientific fields related to communications

- Develop leading-edge products and services

The Wizard’s Invention Factory

Today we are used to idea of corporate and university research centers—well-equipped and funded laboratories where teams of scientists and technicians conduct research and development on tomorrow’s breakthrough technologies. Nothing like this existed, however, until the late 1800s, when Thomas Edison systematized the business of innovation.

Edison set up his first R&D center in Menlo Park, New Jersey, in 1876 with the goal of developing technologies and inventions with commercialization potential. As a way of pursuing innovation, this was itself an innovation. Using his earnings from previous inventions (such as the stock ticker) and investors’ capital, he set up shop in a facility that included a long two-story clapboard building, a smaller brick mechanical shop, some small sheds, and a farmhouse. He stocked these buildings with technical books, machining equipment, laboratory instruments, electrical testing devices, chemicals, and staffed them with more than forty capable mechanics and technicians.

Within five years, Edison had outgrown Menlo Park and moved to a larger facility in West Orange, New Jersey. But during that short period he and his associates had patented four hundred inventions and churned out a number of important commercial successes (as well as some spectacular failures), including the carbon transmitter for the Bell telephone, the phonograph, the tasimeter (a supersensitive heat-measuring device), and the incandescent electric lamp. And Thomas Edison became known as “the Wizard of Menlo Park.” More important, Menlo Park created a model for modern industrial research.

SOURCE: Adapted with permission from James M. Utterback, Mastering the Dynamics of Innovation: How Companies Can Seize Opportunities in the Face of Technological Change (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1994), 59–60.

This mission is typical of corporate-level R&D, which is heavily focused on radical innovation. R&D at the business-unit level, in contrast, generally focuses on incremental projects that will benefit the units directly and in the short-term. Business-unit managers with profit-and-loss responsibilities are either unable or unwilling to shoulder the financial burden of long-term radical innovation projects. They look to corporate R&D for those.

In their study of eleven radical innovation projects, Richard Leifer and his colleagues found that business units were happy to accept a radical innovation hand-off from corporate R&D labs, but only after most of the expensive and time-consuming work had been done.10 The aim of these managers was to improve the performance of the mainstream business—which usually means a focus on incremental innovation.

A formal R&D program is not the only structure for creating innovative ideas. Some companies have generated and developed ideas by temporarily bringing together talented people with different perspectives with the sole purpose of solving a particular problem. (“Idea Contests” shows one way organizations get innovative ideas from within their ranks.) In some cases, these individuals are located in remote or isolated settings to keep team members focused on their mission, to minimize interference from the rest of the organization, provide autonomy, or to maintain secrecy. The term skunkworks is often applied to these focused project teams. The term was first coined in 1943 by Lockheed Aircraft Corporation (now Lockheed Martin) to describe the project center it used to develop the first U.S. fighter jet, the XP-80. Lee Sage has described a similar situation at Johnson Controls, Inc. (JCI), a major supplier of vehicle interiors to the auto industry. Besides its corporate mission, JCI had a dual goal of using more recycled materials and producing zero landfill wastes. To further that goal, it wanted to create a new material for its products, and chose to do so through a skunkworks project. As told by Sage: “[T]he company identified 30 engineers it viewed as competent and creative in the materials area, set them up in an unused company building in Holland, Michigan, and asked them to come up with a new and suitable car interior material. . . .”11

Idea Contests

Most business students are familiar with business plan contests. Individual students or student teams create ideas for new start-up businesses. They develop these into formal business plans and submit them to a panel of professors and local venture capitalists. These contests are good practice for would-be entrepreneurs. Better still, the top plans are rewarded with cash prizes—seed money with which to develop their ideas into real businesses.

This same contest concept has been applied in corporations to generate ideas with commercial potential. The Corporate Technology department of Siemens carried out one of these contests in 1996 as part of a companywide innovation initiative. Fourteen hundred Siemens employees in Europe and the United States participated. Here’s how it worked: the company put out a call for innovative ideas for new products, processes, services, and systems that could be realized in two or three years. No basic research ideas were allowed. Ideas submitted for the contest could be for new businesses or enhancements to old ones. Within four months, 245 ideas had been submitted. These were screened by a jury of eighteen experts who collaborated with appropriate business units. Forty-six ideas survived this jury “stage gate” and went to personal presentations to senior management, which selected six finalists. All finalists received seed money with which to develop their ideas further.

SOURCE: Jörg Schepers, Ralf Schnell, and Pat Vroom, “From Idea to Business—How Siemens Bridges the Innovation Gap,” Research-Technology Management 42, no. 3 (May–June 1999): 26–31.

JCI’s skunkworks eventually produced CorteX, an energyabsorbing material made from recycled plastic soft-drink bottles and carpeting. CorteX found its way into vehicle overhead systems, door panels, and other auto interior features developed by the company. This idea-generation experience was so successful that JCI adopted it again—this time for a one-year project to create innovations in vehicle seats.

Tips on Where to Look for Innovative Ideas

Are you having trouble finding innovative ideas for your business? Every one of the ideas sources described in this chapter can help you. Other places to look include:

- Wherever a new technology and customer needs intersect: Global positioning satellite (GPS) technology was developed for military navigation. This technology and the need of auto drivers to know their locations relative to destinations created a new product option on luxury automobiles. Within just a few years it had become a standard feature.

- Either-or propositions: Remember when manufacturers told us that we could either have high quality or low price—but not both? Remember when carmakers said that we could either have a large fuel guzzler or a tiny fuel-efficient vehicle? Each of these either-or propositions crumbled as innovators found opportunities within what proved to be false assumptions. What either-or propositions are limiting the choices of your customers today?

- Demographic change: Aging populations in North America; Europe; and Japan, South Korea, and some other Asian countries have created opportunities for applying existing technology to new uses. In the United States, for instance, this demographic shift has prompted some home builders to examine how they design kitchens, bathrooms, and closets from the perspective of older residents who may have trouble reaching high shelves, negotiating steps, and getting in and out of showers. Innovations in the cosmetic surgery, pharmaceuticals (think Viagra), dental implants, replacement heart valves, and bone-anchored micro hearing aids have all emerged in the shadow of a substantial demographic change.

- Market change: The big Wall Street firms laughed when Charles Schwab created his no-frills discount brokerage service. Schwab correctly recognized that more and more successful baby boomers were developing nest eggs and looking for places to put them. His do-it-yourself brokerage service appealed to many of these affluent boomers.

- Fundamental pricing shifts: The rising price of oil—coupled with the threat of global warming—has catalyzed an unprecedented level of research and practical innovation, confirming a general understanding that innovation is most likely to occur where the rewards of innovation are greatest. The rapid escalation in petroleum prices, from $20 per barrel in May 1999 to $146 in the summer of 2008, was a disaster for airlines, trucking companies, makers of gas-guzzling SUVs, and everyone else whose business model depended on low-cost oil. But that huge pricing shift produced opportunities for innovators in transportation, alternative energy production, lighting, residential and commercial construction, and countless other fields. That period witnessed the introduction of energy-saving LED and compact florescent lights, the Honda/Climate Energy Freewatt hybrid home heating/electricity-generating system, cleaner diesel engines, concentrated solar power electric generation, and thousands of other breakthroughs.

Open Market Innovation

Not everything must be “invented here.” Innovative ideas can often be acquired (or sold) in the open market. Bain & Company’s Darrell Rigby and Chris Zook coined the term open market innovation in describing how companies can reach outside for the ideas they need for new products and services. As described by Rigby and Zook in a Harvard Business Review article, open market innovation employs licensing, joint ventures, and strategic alliances to bring the benefits of free trade to the flow of new ideas.12 For example, confronted with the anthrax scare that first hit the United States in late 2001, Pitney Bowes—a major producer of mail metering systems—had no ideas about how to help customer organizations whose mail put employees at risk. Needing ideas and solutions fast, it looked outside for help. With the collaboration of outside inventors, it quickly developed scanning and imaging technologies capable of spotting contaminated letters and package.

As described by Rigby and Zook, open-market innovation has four distinct advantages:

- Importing new ideas can help you multiply the “building blocks” of innovation.

- Exporting ideas is a good way to raise cash and keep talent.

- Exporting ideas gives companies a way to measure an innovation’s real value.

- Exporting and importing ideas helps companies clarify what they do best.13

There are, of course, risks associated with collaborating across organizational boundaries. Key among them is the danger of failing to adequately capitalize on ideas shared with others in the open market. The best safeguard against this danger is a deal structure that protects your interests.

Open market innovation can also tap the creativity of suppliers, university and government labs, and other sources through what Larry Huston and Nabil Sakkab call the “connect and develop” method. As they explained in a 2006 article on this subject, Procter & Gamble had innovated for decades from within, employing global research facilities staffed by some of the best talent.14 In 2000, management saw the need for a new approach; it dispensed with the company’s age-old “invent it ourselves” approach to innovation and embraced a “connect and develop” model. By identifying promising ideas throughout the world and applying its own capabilities to them, P&G realized it could create better and cheaper products, faster. The result is that the company now collaborates with suppliers, competitors, scientists, entrepreneurs, and others (that’s the connect part). It systematically scours the world for proven technologies, packages, and products that P&G can improve, scale up, and market, either on its own or in partnership with other companies. Thanks in part to this approach, R&D productivity at Procter & Gamble increased by nearly 60 percent. As described by Huston and Sakkab, P&G launched more than one hundred new products in 2004 and 2005 for which some aspect of development came from outside the company.

If you adopt this method, consider this advice:

- First, identify consumer needs: Clarify what you’re looking for before you begin scouring the world for ideas. Ask business-unit leaders which consumer needs, when satisfied, will drive their brands’ growth. Translate needs into briefs describing problems to solve. Consider where you might seek solutions. For example, P&G unit managers identified a need for laundry detergent that cleans effectively in cold water. They decided to search for relevant innovations in chemistry and biotechnology solutions that enable products to work well at low temperatures. Possibilities included labs studying enzymatic reactions in microbes that thrive under polar caps.

- Identify adjacencies: Ask which new product categories, related to your current categories, can enhance your existing brand equity. Then seek innovative ideas in those categories. For example, P&G expanded its Crest brand beyond toothpaste to include whitening strips, power toothbrushes, and flosses.

- Leverage your networks: Cultivate both proprietary and open networks whose members may have promising ideas. P&G’s proprietary networks, for example, include its top fifteen suppliers, who collectively have fifty thousand R&D staff. P&G created a secure IT platform to share problem briefs with these suppliers—who can’t see others’ responses to briefs. P&G’s open networks include NineSigma, a company that connects interested corporations with universities, government and private labs, and consultants that can develop solutions to science and technology problems. NineSigma creates briefs describing contracting companies’ problems and sends them to thousands of possible solution providers worldwide.

- Distribute and screen ideas: Once you have identified ideas for refining and further commercializing existing products or for employing technology solutions to create new products, distribute those ideas internally—ensuring that managers screen them for potential. For example, at P&G, product ideas are logged on P&G’s online “eureka catalog” through a template that documents pertinent facts—such as current sales of existing products or patent availability for a new technology. The document goes to P&G general managers, brand managers, and R&D teams worldwide. Product ideas are also promoted to relevant business-line managers, who gauge their business potential and identify possible obstacles to development.

The Role of Mental Preparation

Many ideas are generated unintentionally through random observations, routine contacts with customers, and even unintended laboratory results. However, to quote Louis Pasteur, “Chance favors the prepared mind.” A prepared mind is more likely to formulate a problem-solving idea or recognize an opportunity.

The value of a prepared mind is underscored by the invention of 3M’s fabric protector, Scotchgard, a development triggered by a 1953 laboratory accident. Researcher Patsy Sherman was conducting fluorochemical polymer experiments when a lab assistant accidentally spilled some of the solution on her tennis shoes. Sherman tried to remove it using soap and water, alcohol, and other solvents, but nothing worked. As often happens in cases where the people involved have technical training, keen powers of observation, and native curiosity, a light went on in Sherman’s mind. She reasoned that if the substance was impervious to solvents and other substances, it also might protect textiles from stains. Further development of the substance led to a successful new product.

Tips for Developing Innovative Ideas

Authors Scott Anthony, Matt Eyring, and Lib Gibson offer the following tips for seeking opportunities for disruptive, or industryaltering, innovative ideas:

- Make it easier and simpler for people to get important jobs done: Look for people who are frustrated by jobs they must do. For example, many people were frustrated when they had to wait several days to receive an important repair part, a notarized document, or some other item in order to complete their work. Overnight express delivery (e.g., FedEx), has solved that problem for millions each day.

- Find ways to prosper at the low end of an established market: Not everyone needs or can afford the level of performance offered by successful, established products. This is particularly true for people in low-income economies. The LifeStraw, a simple $2 item, has given the estimated one billion people who lack access to clean drinking water a low-cost way to obtain safe water without spending large sums on more advanced, electricity-dependent systems. The success of micro lending—i.e., lending sums as little as $100 to entrepreneurs in third-world countries—provides a similar example.

- Remove barriers to consumption: Some products and services can be obtained only through expensive intermediaries. For example, not long ago, a woman who wanted to know if she was pregnant had to make an appointment and have a test done at a clinic or doctor’s office. Today, she can do the test herself with an easy-to-use, low-cost kit available at any pharmacy. A lack of skills can also be a barrier to consumption. Intuit discovered this problem with existing small business accounting and bookkeeping software. Lacking skills, many small business owners had no choice but to hire professionals. Intuit lowered the skills barrier when it developed its hugely successful QuickBooks product.

SOURCE: Scott Anthony, Matt Eyring, and Lib Gibson, “Mapping Your Innovation Strategy,” Harvard Business Review, May 2006.

Preparation is often cited as the first step in the creative process that leads to innovation. To prepare themselves for idea generation, would-be innovators should immerse themselves in the problem at hand. According to an article by Arthur Shapero, an expert on managing creativity, they should:

- Search the literature

- Look at all sides of the problem

- Talk with people who are familiar with the problem

- Play with the problem

- Ignore the accepted wisdom15

How Management Can Encourage Idea Generation

If innovation is a key function of companies, then management has a responsibility to encourage the generation of innovative ideas. Both traditional and nontraditional tools can be used for that task: rewards, a climate of innovation, hiring innovative people, encouraging the cross-pollination of ideas, and providing support for innovators. Management’s responsibilities in the area of innovation are treated extensively in chapter 14, nevertheless, let’s consider here some of the things that management can do to encourage the idea generation part of the process.

Rewards

Reward idea generators with pay and/or promotions. Rewards provide a clear signal that good ideas are important. Monetary rewards appear to be more effective when they are performance-based and when they give employees a personal stake in organizational success. Many innovative companies, 3M being one example, use dual career ladders—technical and managerial—to reward innovative behavior. They realize that not everyone is cut out to be a manager, nor wishes to be one.

Rewards for innovators, however, should encompass more than pay and promotions. Pay and promotion prevent feelings of being taken advantage of, but they do not drive the free thinking needed for innovation. For many people, the rewards that lead to innovation involve greater freedom: to explore hunches, to pursue one’s curiosity, to travel to technical conferences, to mingle with customers and lead users, and so forth. Access to greater resources is also an effective reward when innovation is the goal.

A Climate of Innovation

Management determines the organizational climate. Innovative organizations have these characteristics:

- Management sends a clear message that the well-being of the company and its employees depends on continuous innovation.

- People aren’t afraid to try or suggest new things.

- No one feels a sense of entitlement for just showing up for work.

- There is a visceral discomfort with current success—a nagging sense that it may not last.

- People rise and fall on their merits and contributions.

- Employees are outward looking; they seek ideas and best practices among competitors, through professional contacts, and within other industries.

If the climate of your company lacks these characteristics, change it.

Hire Innovative People

Some people are better at generating ideas than others. Ed Roberts and Alan Fusfeld identified the personal characteristics of idea generators; these individuals:

- Are experts in one or two fields

- Enjoy doing innovative work

- Are usually individual contributors

- Are good problem solvers

- Find new and different ways of seeing things16

Many of these characteristics can be identified in the normal hiring process: in résumés, hiring interviews, and reference checks. So be on the lookout for them. Look in particular for these individuals:

- Engineers with broad interests who can bridge the boundaries between technical disciplines

- Technical people who nevertheless like to meet customers and wrestle with their problems

- Continual learners

As a general rule it’s wise to avoid hiring hyperspecialists—people who want to learn more and more about less and less. Also, avoid hiring anyone who has no interest in customers or their problems.

Management can also encourage ideas by avoiding policies and practices that make creativity unlikely. For example, if people are operating under a dark cloud of fear, drive out that fear. Some managers create fear by punishing failure, which only encourages people to play it safe and take no risks. Robert I. Sutton suggests something different: he recommends that managers reward success and failure, but punish inaction.17 He cites the advice of IBM’s legendary founder, Thomas Watson, who told people, “If you want to succeed, double your failure rate.” Thus, every failure brings you closer to success; inaction will get you nowhere.

If there is a “suits versus lab coats” mentality in the workplace, management should spend more one-on-one time with the lab coats. If people are being driven to 120 percent of capacity, lighten up; create space for musing.

Encourage the Cross-Pollination of Ideas

Ideas and knowledge often produce little when they are isolated in organizational pockets, but something magical happens when they are allowed to float free. Formerly isolated ideas come together to produce something new. You can encourage this cross-pollination of ideas by any of the following means:

- Periodically reassign technical specialists to different work teams. The resulting interactions often lead to insights, or the novel application of one technology to another.

- Send people to professional conferences and scientific convocations.

- Set up an intracompany knowledge management system—this makes knowledge and experience captured in one area available to everyone.

- Sponsor events that bring outside experts to your company to give lectures and workshops—what they have to share often catalyzes ideas within the company.

- Arrange periodic customer site visits and field trips to observe best practices in other industries.

- Meet with local inventors and entrepreneurs in your field.

- Seek out consultants with different perspectives.

- Invite university professors on sabbatical to temporarily join your group or participate in brainstorming sessions.

Each of these approaches takes advantage of the power of networking. 3M, which has maintained a high level of innovation for over one hundred years, views formal and informal networking among its scientists as one of its secret weapons. In 1951 it institutionalized the formal part of its network with the creation of the Technical Forum. The Forum hosts an annual symposium to which all of the company’s R&D personnel are invited and given an opportunity to learn what their colleagues in other technical fields are working on (the company supports more than forty-two technical fields) and to build personal relationships and better communication between scientists. That sort of communication and knowledge sharing has resulted in researchers taking an idea from one realm and applying it to another. For example, 3M scientists have used a technology initially developed for layered plastic lenses to create more durable abrasives.

Support Innovators

Just as artists have always needed the help of wealthy patrons to pursue their muses, innovators need the support of highly placed managers. Without that support, many ideas die on the vine.

Management support need not—and often should not—take the form of formal funding and staff resources, particularly in the early stages. But senior managers can provide the resources that innovators need to “bootleg” unofficial development of their ideas:

- Unused space in which to conduct experiments

- Small sums for equipment and part-time help

- Time away from regular duties in which to pursue an idea

Senior managers can also protect worthy ideas from the organizational mechanisms that kill off ideas. What are these mechanisms?

- A negative view of ideas that don’t serve existing customers: This is the “tyranny of served market” syndrome again. Antidote: Remind people that current customers are just a segment of the customer universe. The new idea may be just the ticket for another segment. Also remember that current customers who don’t like the new idea may change their tune once the idea is perfected and competitively priced.

- The new idea threatens the current business: “If we did this we’d simply cannibalize our existing sales.” Antidote: Remember that if you don’t eat up your current business with different (i.e., superior) products, someone else will. Wouldn’t you rather keep that revenue than give it away?

- The market potential seems too small relative to the size of the existing business: Big companies miss out on many important innovations because the potential is viewed—often erroneously—as too small. “We’re a $2 billion company. Why would we mess around with something that might only contribute $5 million to sales?” This is a powerful argument, since companies need to maintain focus. Antidote: Remember that many innovations initially appeal to small niches, but expand as the technology improves and customers find new and unanticipated uses for them. For example, initial market research on a new-fangled machine called the “computer” indicated world demand for only ten machines; the only imagined customers were national defense and scientific organizations. Likewise, the Internet was initially conceived of as a communications link for the academic/scientific community.

Four Idea-Generating Techniques

Companies use a variety of techniques to generate new ideas. Four are offered here: brainstorming, nominal group technique, TRIZ, and catchball.

Brainstorming

Most readers have had some experience with brainstorming, a method of soliciting ideas from a group of individuals in rapid fashion that does not examine ideas as they emerge Effective brainstorming is guided by five key principles:

- Focus: Brainstorming should concentrate on a particular problem or opportunity and be bounded by real-world constraints.

- Suspended judgment: All judging should be suspended while ideas are being generated. Even the wildest ideas should be encouraged.

- Personal safety: Participates should be assured that unpopular ideas or ideas that threaten the status quo will not provoke recriminations.

- Serial discussion: Limit the discussion to one conversation at a time and keep it focused on the topic.

- Build on ideas: Try to build on the ideas of others wherever possible.

Brainstorming techniques fall into several broad categories: visioning, modifying, and experimenting. Each category uses a slightly different thought process, but there are some common features. Modifying and experimenting techniques, for example, start with existing data and use intuitive insights to draw ideas from those facts. Vision techniques use the intuitive process first, and then follow up with information gathering and data analysis.

VISIONING. This approach asks people to imagine, in detail, a long-term, ideal solution and the means of achieving it—for example, a home heating system based on alternative technologies (see worksheet 2-1 for a template for this exercise). The goal is to break free of the ingrained practicality that inhibits innovative thought. Once you’ve generated several ideas that would constitute that ideal solution, participants can then discuss what it would take to make those ideas happen.

WORKSHEET 2-1

Visioning techniques worksheet

These techniques help participants imagine the future, usually the ideal future.

Wish list

Generating wishes

Ask people to “let themselves go” and imagine an ideal situation in which, for example, they would be granted any wish they want by a fairy godmother, by winning the lottery and having unlimited resources, or by whatever else sets the tone. Select a quiet place without interruptions, or play soothing background music.

Exploring the possibilities

Encourage everyone to review their lists: what did they discover about themselves or the situation? Then take it another step: what would it actually take to make this wish come true?

The ideal scenario

Ask the group to imagine what the ideal future or solution would look like. This can be done with words or with images. For example, participants could pour through visually rich magazines, select images and paste them together in a collage. Follow the creation with discussion and exploration.

Time machine

Alternatively, ask participants to pretend that they can time travel to 5–7 years into the future. What would the situation look like then? What would have been accomplished? Add whatever questions are relevant to the creative challenge being explored.

SOURCE: Harvard ManageMentor® on Innovation © 2000 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College and its licensors. All rights reserved. Inspired by tools in William C. Miller, Flash of Brilliance (Reading, MA: Perseus Books, 1999).

MODIFYING. Visioning techniques begin by assuming that there are no constraints. Modifying techniques, on the other hand, begin with the status quo—with current technology or conditions—and try to make adaptations. One good way to see how your current product or service could be modified is to look at it from the customer’s perspective. Consider every feature of the product or service and how that feature adds or diminishes value for you.

EXPERIMENTING. Experimenting helps people to systematically combine elements in various ways and then test the combinations. One such approach involves creating a matrix. For example, a car-wash owner in search of a new market or market extension would begin by listing parameters across the top: method, products washed, equipment, and products sold; under each parameter, he lists all the possible variations he can think of. Under the equipment category, the variations might include sprays, conveyors, stalls, dryers, and brushes; the products washed category might include cars, houses, clothes, and dogs. The resulting table allows the owner to put together new business possibilities using alternatives listed under the columns. Thus, he might decide to start a service for boat owners to wash their boats using the existing stalls and brushes.

Nominal Group Technique

Brainstorming is a proven and popular technique for drawing ideas out of individuals and getting people to talk about those ideas. Its informality makes it easy to apply. However, the method depends on people speaking up and contributing in a group setting. Unfortunately, many brainstorming participants, for one reason or another, will not speak up. Some fear appearing stupid. Others lack confidence in their ideas or want to withhold those ideas until they’ve developed them to a higher level. Still others remain silent when their ideas are in opposition to those advocated by more powerful members of the group or by the group’s consensus. Whatever the reason, the group setting of brainstorming has a way of silencing some people.

A remedy for this problem is nominal group technique (NGT). Like brainstorming, NGT aims to evoke ideas and problem solutions from participants. But NGT is designed to evoke participation from all members of the group. Here’s how it works. Twelve or fewer people are seated around a table, with one acting as facilitator and another as recorder. Unlike brainstorming, participants are not asked to orally contribute; instead, they are told to write down their ideas and give them, anonymously, to the recorder. Thus, all participants, including people who may be reluctant to speak up in front of a group, share their ideas.

Once the recorder has collected all the ideas in written form, the facilitator reads them to the entire group. Participants are asked to rate each idea in order of perceived value, using a 0 to 10 scale. These ratings are returned anonymously to the recorder, who totals each idea’s ratings and posts them for all to see. Participants then discuss the ideas in a normal way. They know how the group rated each idea, but still have no clue about who offered them or who gave a high or low rating.

NGT has two benefits relative to brainstorming:

- A few big talkers or politically powerful people are less likely to dominate the idea pool and the discussion.

- NGT achieves participation from everyone, including those who might not offer ideas to a large group.

TRIZ

One weakness of both brainstorming and NGT is their randomness. Whether the thoughts flying out from the minds of participants contain anything useful or connect with other thoughts in ways that spark useful insight is not controllable or predictable. This weakness has encouraged some to embrace a theory of inventive problem solving, or TRIZ. TRIZ was developed in Russia by scientist Genrich Altshuller and his colleagues over several decades, beginning in the late 1940s. This method systematically solves problems and creates innovation by identifying and eliminating what Altshuller called technical contradictions.18

One popular example of the TRIZ method is the development of the incandescent lamp by Thomas Edison in the late 1800s. Earlier tinkerers knew that they could create light by passing electricity through a conductive medium, such as a metal wire filament. The contradiction, in this case, was the fact that the wire would quickly burn up. Edison eventually resolved this contradiction by placing his wire within a vacuum tube and finding filament material with a practical working life (in this case, carbonized thread).

Undocumented reports state that sixty thousand engineers around the world are trained in TRIZ methods, and enthusiasts cite its use by many big-name industrial companies as evidence of its effectiveness.

Catchball

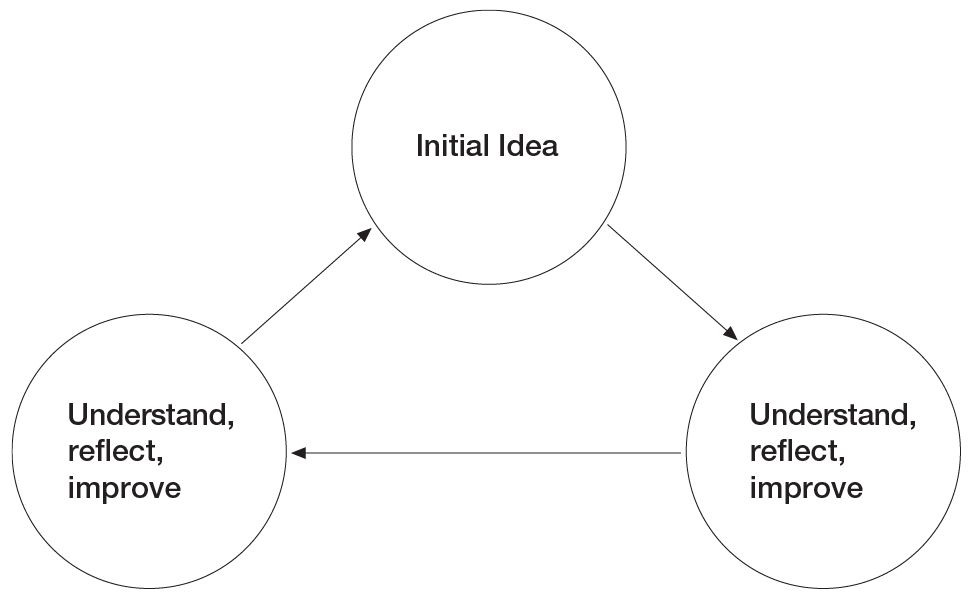

Among their other contributions to management methods, the Japanese have given us catchball. Catchball is a cross-functional method for accomplishing two goals: idea enrichment/improvement, and buy-in among participants.19 Once you’ve generated an idea, you can build and improve on it using this method.

Here’s how it works. An initial idea is “tossed” to collaborators for consideration, as in figure 2-1. The idea may be a new strategic goal, a new product, or a way to improve some work process. Whoever “catches” the idea assumes responsibility for understanding it and improving it in some way. That person then tosses the improved idea back to the group, where it is again caught and improved still further. And around it goes in a cycle of gradual improvement. As people participate, they develop a sense of shared ownership and commitment to the idea that takes form.

Catchball’s underlying principle goes back to the Socratic method of dialogue first articulated by Plato. Try using it the next time your organization needs to develop a raw idea and get people committed to it.

Catchball

Summing Up

Ideas are the nutrients of innovation. You can’t get anywhere without them. And in the innovation race, organizations with many good ideas to pick from have a real advantage. This chapter has examined key sources of innovative ideas:

- New knowledge: Though the trail from new knowledge to marketable products is often long, this is the source of many, if not most, radical innovations.

- Customers’ ideas: These ideas can tell you where current products fall short and point to unmet needs.

- Lead users: These are people (or companies) whose needs are far ahead of market trends. Look at what they’re doing today to meet needs that others many discover tomorrow.

- Empathetic design: This is an idea-generating technique whereby innovators observe how people use existing products and services in their own environments. So try going out and observing how customers and potential customers do things and attempt to solve problems.

- Invention factories and skunkworks: These are R&D labs and special projects with singular missions and their own quarters.

- Open market innovation: Open market innovation relies on the free trading of ideas between entities through licensing, joint ventures, and strategic alliances.

- Idea-generating techniques: Such techniques include brainstorming, nominal group technique, TRIZ, and catchball.