Introduction

Innovation has shaped human society and daily life in every age. Its power is such that historians and archeologists today define broad periods of human history in terms of the innovations that have distinguished them: the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, the Iron Age, the Industrial Age, the Atomic Age, the Digital Age, and so forth. While each of these labels refers to a technology, innovation is much broader than technology. Indeed, the impact of innovation can be seen over the centuries in such diverse areas of human endeavor as religion, social organization, architecture, military tactics, medicine, agriculture, and the arts.

Even periods popularly regarded as stagnant have been altered importantly by technological innovation. For example, the heavy moldboard plow, the three-field system of crop rotation, the stirrup, and vertical- and horizontal-axle windmills were all either invented or adopted in northern Europe during the early Middle Ages, and each created substantial change in people’s lives. Let’s consider two of these.

Historians believe that the heavy moldboard plow originated among the Slavs and was introduced by seventh-century Goths to northern Europe, where the soil was almost impenetrable to the “scratch plow,” the prevailing technology of the day. The scratch plow had been used in southern climes since Roman days. Its key feature was a vertical, triangular “share” (iron or wood) which, dragged behind a pair of oxen, was adequate for cutting a narrow furrow in the dry, thin soils of the Mediterranean region. But for the heavy, damp earth of northern Europe, something more robust was required. The moldboard plow had three basic elements: a coulter, or heavy vertical knife, that cut into the soil; a plowshare set at right angles to the coulter for horizontal cutting; and a moldboard designed to turn the heavy earth to one side. This new device greatly increased agricultural productivity in transalpine Europe and allowed farmers to cultivate fertile alluvial areas that until that time had been unworkable.

The stirrup was another innovation that altered society in medieval Europe. According to the late historian Lynn White Jr., the eighth-century introduction of the iron stirrup from India gave the mounted warrior battlefield ascendancy. Using stirrups for support, he could deliver a blow, not with the strength of his own arm, but with the vastly greater power of his horse.1 This greater capacity altered the role of the mounted warrior, who since ancient times had been limited to scouting and flanking. The armored man on horseback was now the master of the battlefield, and that mastery quickly spilled over into social and political power. The medieval knight would remain at the pinnacle of society and warfare until the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, when new innovations—the tactical use of the Welsh longbow, and then firearms—changed the game.

Though the term innovation entered the English vocabulary in the fifteenth century, it’s probably safe to say that few people prior to the nineteenth century used it regularly. Not so today. The term is now used routinely and is the subject of university courses, scholarly studies, books, and articles. Recognizing that innovation is the catalyst of economic progress and national competitiveness, government and business leaders demand innovation and periodically launch programs to encourage more of it.

The Role of Innovation in Enterprise

Innovation that the marketplace values has long been recognized as a creator and sustainer of enterprise. Every time Intel’s engineers produce a new generation of computer chips that customers value, its fortunes are renewed. Whenever a pharmaceutical company introduces a drug that restores the health of millions around the globe, it too gains a new lease on life. When a PC service firm thinks of a way to fix a customer’s computer software over the Internet, that company opens up a new channel for growth.

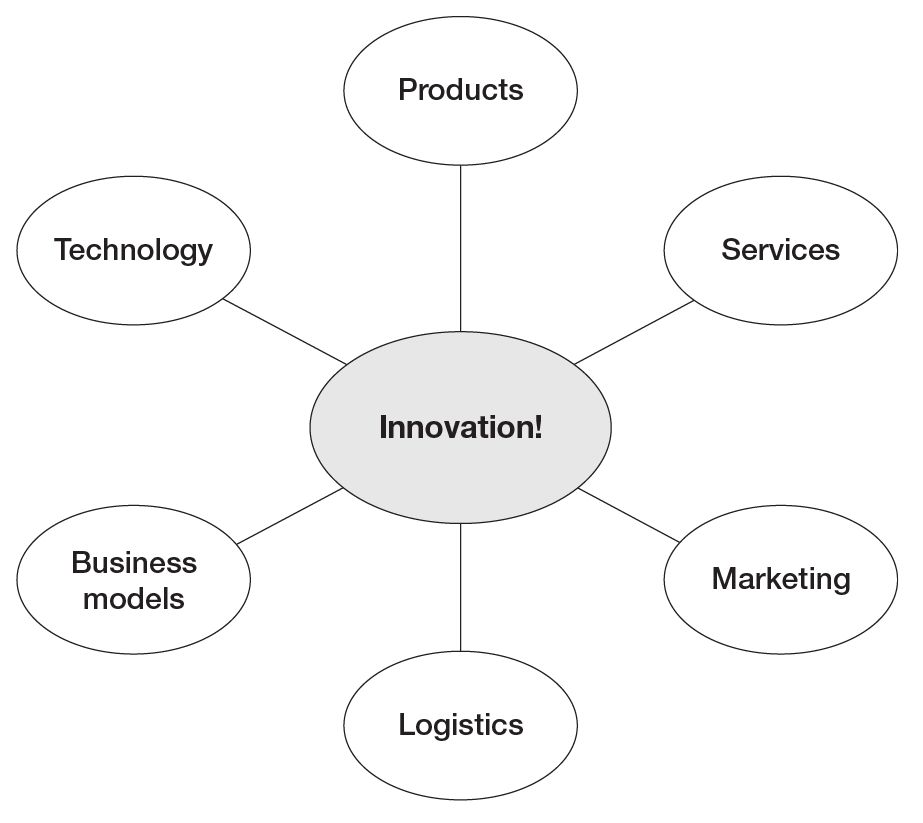

Innovation takes place on many fronts (figure I-1). Product innovations in assembled products—iPods, industrial robots, solar energy–generating arrays—are the type that most often come to mind. But innovation is prevalent in:

- Technology: The last several waves of economic growth have been stimulated by technological innovations in different fields: semiconductors (the computer revolution), biotechnology (based on new scientific knowledge), the Internet (the product of a government program), and telecommunications. Innovation in energy technology may be the next big wave.

Innovation on many fronts

- Services: Services now constitute roughly half of the U.S. economy and are fertile ground for innovation. Individuals and pension funds, for example, have invested billions in a dazzlingly varied mutual fund industry that barely existed thirty years ago. That service industry owes much of its success to financial concepts of portfolio management developed at leading schools of business and economics.

- Processes: The low manufacturing costs of paints, chemicals, petroleum-based fuels, glass, and countless other nonassembled products and services are the result of continuous process innovation over many years. Assembled goods have likewise benefited from process innovations that have reduced assembly steps and labor costs and improved reliability.

- Marketing and distribution: Viral marketing (a technique that uses existing social networks to increase brand awareness), overnight delivery service (FedEx is the notable pioneer), and direct distribution via the Web are all based on innovations in marketing and logistics.

- Business models: Apple’s approach to generating revenue from iTune downloads of music files, films, and audiobooks rivals Dell’s innovative business model in the field of computers and peripherals. Likewise, Amazon’s e-book venture, Kindle, represents a new model for generating revenues from text content.

- Supply chains: Wal-Mart eclipsed its retail competitors by doing many things right. One of those things was the development of a superefficient supply chain that forged fast and efficient connections between the production facilities of key suppliers with the loading docks of Wal-Mart stores. This justin-time supply system assures that goods are on the shelf when people want them and eliminates costly stockroom inventories.

But while innovation creates, it can also destroy. More than a half-century ago, economist Joseph Schumpeter described the economic, sociological, and organizational impacts of innovation and its “winds of creative destruction.” Those winds sweep away both old ways of doing things and the enterprises and institutions that cling to them. During the nineteenth century, innovations in mass production doomed local shoemakers, dressmakers, and many other artisans. We see that pattern repeated today as “superstores”—a retail innovation—devastate the ranks of small local hardware stores, independent electronic/appliance stores, and office-supply shops. Likewise, innovations in electronics, pharmaceuticals, and other fields—including services—continually undermine established products and services. Enterprises that fail to keep pace with these innovations are quickly swept from the field.

The Innovation Process

The innovation process

Many managers, technical professionals, and scholars see innovation as a process like the one mapped in figure I-2. That process begins with a creative act: recognition of an opportunity. Opportunity recognition often emerges from someone’s understanding of a market need. As an executive of the E. Remington and Sons (later the Remington Arms Company) remarked on witnessing a demonstration of a prototype typewriter, “There’s an idea that will revolutionize business!” A similar recognition took place when Thomas Edison witnessed the blazing illumination produced by William Wallace’s arc lighting system, an impressive but impractical predecessor to the incandescent lamps that Edison would eventually develop. Edison immediately foresaw the commercial potential of electric lighting and launched an intense and tireless effort to exploit it.

Opportunity recognition may also originate from a scientist’s or engineer’s technical insight. For instance, frustration with conventional thinking about the performance limits of silicon-based semiconductors inspired IBM researcher Bernard Meyerson to experiment with a silicon germanium alloy. The commercial applications of that technology were understood only later.

Once an opportunity is recognized, other process steps follow. The innovative concept must be fleshed out in detail, problems must be solved, and a workable prototype must be developed and tested to the point where it can be evaluated by potential customers. Each of these steps must be enlightened by market/customer and technical understandings.

Decision makers play a role throughout the innovation process, as supporters and as askers of tough questions:

- Will the idea work?

- Does the company have the technical know-how to make it work and the business competencies to make it successful?

- Does the idea represent value for customers?

- Does the idea fit within the framework of company strategy?

- Does it make economic sense for the company?

- Will this innovative project open the door to others or to new markets?

Ideas that produce affirmative answers to these questions and that obtain organizational support are moved further along the road toward market launch. Some make it to the end of that road; most do not. Commercial launch is the final test for innovative ideas. Here, customers make the final evaluation.

Creativity plays a role in the innovation process, though one that is difficult to measure. Creativity sparks the innovative idea and it helps to improve facets of the idea as it moves forward. Creativity is needed on both the technical and market sides of the process. It helps the technologist to see new ways of addressing known customer needs even as it helps customer-facing people find new ways of applying or adapting existing technologies to those needs.

The Challenge to Business Leaders

Unfortunately, top managers seldom play a creative role in the innovation process. Most are too removed from day-to-day customer interactions to be the first to recognize an innovative market opportunity. And, excepting R&D executives, their technical skills may trail behind the cutting edge. Nevertheless, by virtue of their authority to make decisions and to allocate resources, senior leaders are duty-bound to participate in the innovation process. They must stay abreast of technological currents, market insights, and the ideas being debated by their subordinates. Equally important, they must create an organizational climate that encourages experimentation, accepts some level of failure, discourages complacency, and accommodates inventive people who for one reason or another don’t quite fit in. Doing all this while tending to day-to-day affairs of the enterprise may be the ultimate challenge of business leadership.

What’s Ahead

This book examines the concept of innovation and offers practical suggestions for fostering and aligning it with enterprise strategy. Its content draws on parts of Managing Creativity and Growth, an earlier book in the Harvard Business Essentials series, but expands the range of discussion and introduces the strategic issues that every innovator must understand and that every leader must communicate. The book’s goal is to make you and your organization more creative and more effective on the all-important innovation front.

As a single volume on a broad topic, The Innovator’s Toolkit will not make you an expert, but it will give you information you can use to be more effective in stimulating innovation and creativity and capturing their benefits.

Chapter 1 sets the stage with a working definition of innovation and discussion of its different types: incremental and radical; innovations in products, processes, and services. Chapter 2 focuses on innovative ideas. Here you learn where they come from and how you can generate more of them. Chapter 3 is about idea recognition, the Aha! moment when someone sees value in the idea. Just seeing the value of an idea, however, is insufficient; the idea must find support within the organization in order to obtain the resources needed for development. How innovators can gain support is the subject of chapter 4. This naturally leads into chapter 5, which describes practical methods companies can use to pick through the many valuable ideas that come their way and determine which few are worthy of resource support. The pros and cons of the stage-gate system used by many companies are discussed here.

In chapters 6 through 10 the book turns to the strategic issues that relate to innovation. Chapter 6 is a brief primer on business strategy, explaining four typical strategies and how innovation fits into each. Chapter 7 describes several “strategic moves” that you can consider when seeking market entry and commercial success with an innovative concept. Chapters 8 and 9 consider a thinking tool—the S curve—and how business leaders can use it to understand the technological trajectories they are on, alternative trajectories, and whether they should continue along the same path or leap to another S curve.

Early-stage innovations contain elements of risk and potential return. If you’re an investor, you probably understand these concepts already. Risk and return are bound together. If you invest in stocks, you probably know enough to diversify—that is, to create a balanced portfolio of many stock issues, some with high-risk/high return characteristics, and others with low-risk/low return characteristics. Leaders of large enterprises will wisely do the same with their innovation projects. Chapter 10 offers practical advice on creating balance portfolios of innovative projects.

The book’s final chapters, 11 through 14, are about creativity—the human characteristic that sparks most innovation. What is creativity? How can we recognize it when we see it? What organizational practices encourage or discourage creativity in individuals and groups? What can leaders do to get more of it? The last of these chapters looks at organizational culture, which has so much to do with employee creativity. If culture must change, top management must act. Chapter 14 offers steps they can follow.

Like other books in the Harvard Business Essentials series, this one has useful supplemental material in the back. It features two appendices, a notes section, and a glossary of key terms relating to creativity and innovation. Every discipline has its special vocabulary, and the subject here is no exception. When you see a word italicized in the text, that’s your cue that it’s defined in the glossary. The final supplement, For Further Reading, identifies books and articles that can tell you more about topics covered in these chapters.

Best of luck with your business and future innovations!