One of the many goals of this book is to offer informed advice to those individuals who will ultimately shape US policy in this highly complex domain. To that end, I announced an open call for submissions from individuals who are engaged in protecting their respective nation’s networks from attack on a daily basis, both nationally and internationally.

Providing experts from other countries with a voice symbolizes the international approach to cyber security that has consistently provided the best results in combating cyber intrusions and in identifying the state and nonstate actors involved.

This chapter contains thought-provoking pieces of varying lengths from a naval judge advocate who wrote his thesis on cyber warfare, an experienced member of an international law enforcement agency, and a scientific adviser on national security matters to the Austrian government, as well as my own contribution.

By Jeffrey Carr

Harry: OK, Airport. Gunman with one hostage, using her for cover. Jack?

Jack: Shoot the hostage.

Harry: What?

Jack: Take her out of the equation.

Harry: You’re deeply nuts, Jack.

The fun of movie scenarios aside, consider the same strategy when the hostage is not a human being but a piece of technology or a legacy policy that no one wants to change.

Here’s a new scenario. A state or nonstate hacker attacks US critical infrastructures and Department of Defense networks at will and without fear of detection or attribution. He is able to do this from behind the protection of two very valuable “hostages” or, more precisely, “sacred cows” that US government officials, including the Congress, are loathe to change—using Microsoft Windows and regulating a segment of private industry:

- Hostage 1

The pervasive use of the Microsoft Windows operating system (OS) throughout the federal government but particularly within the Department of Defense, the intelligence community, and privately owned critical networks controlling the power, water, transportation, and communication networks

- Hostage 2

The uninterrupted, sustained economic growth of US Internet service providers, data centers, and domain name registrars who profit by selling services to criminal organizations and nationalistic hackers that prefer the reliability and speed of US networks to the ones found in their own countries

In this case, the best solution, bar none, is to metaphorically “shoot the hostage,” thus denying an adversary both of his weapons (1) malware configured for the Windows OS and (2) his attack platform—the most reliable Internet services companies in the world.

Shoot the first hostage by switching from Microsoft Windows to Red Hat Linux for all of the networks suffering high daily-intrusion rates. Red Hat Linux is a proven secure OS with less than 90% of the bugs found per 1,000 lines of code than in Windows. Many decision makers don’t know that it is the most certified operating system in the world, and it’s already in use by some of the US government’s most secretive agencies. Computers are changed out every three to four years on average anyway, so the monetary pain is probably not as great as it might seem. The benefit, however, would be immediate.

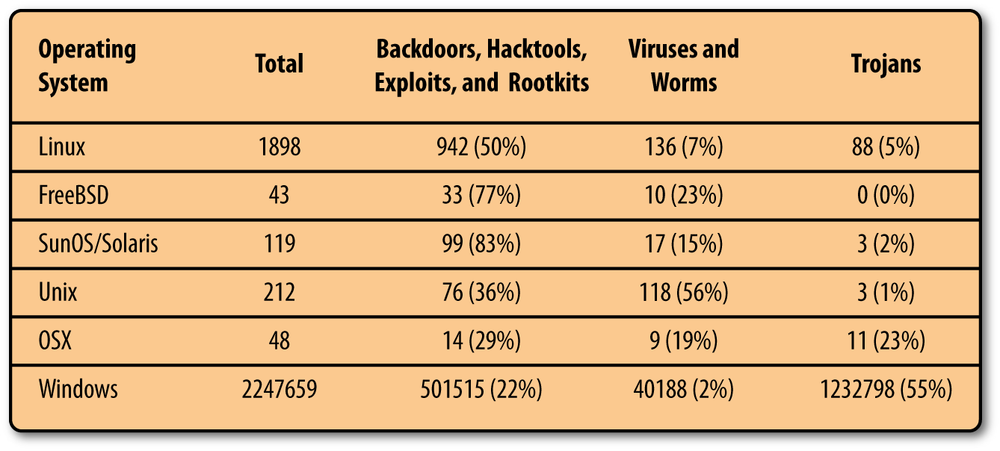

The data from Kaspersky Lab in Figure 13-1 shows how few malware have been developed for operating systems other than Windows. Linux certainly has its vulnerabilities, but the math speaks for itself. Shoot Windows and eliminate the majority of the malware threat with one stroke.

Shoot the second hostage by cracking down on US companies that provide Internet services to individuals and companies who engage in illegal activities, provide false WHOIS information, and other indicators that they are potential platforms for cyber attacks.

The StopGeorgia.ru forum—whose members were responsible for many attacks against Georgian government websites, including SQL injection attacks that compromised government databases—was hosted on a server owned by SoftLayer Technologies of Plano, TX.

The distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks of July 2009 that targeted US and South Korean government websites were not controlled by a master server in North Korea or China. The master server turned out to be located in Miami, FL.

ESTDomains, McColo, and Atrivo—all owned or controlled by Russian organized crime—were all set up as US companies with servers on US soil.

The Russian criminal underground prefers to host their web operations outside of Russia to avoid prosecution. And the robust US power grid, cheap broadband, and friendly business environment makes this country the ideal platform for cyber operations against any target in the world, including the US government.

Congress needs to send a strong signal to US Internet hosting and service provider companies that profit must be tempered by due diligence and that they are, effectively, a strategic asset and should be regulated accordingly.

Neither of these recommendations is politically safe. However, the United States is now facing a serious threat from a new domain with so many evolving permutations that senior leadership, both civilian and military, seem to be standing still. And that’s absolutely the wrong strategy to employ.

By Lieutenant Commander Matthew J. Sklerov [40]

Cyberspace is a growing front in 21st-century warfare. Today, states rely on the Internet as a cornerstone of commerce, communication, emergency services, energy production and distribution, mass transit, military defenses, and countless other critical state sectors. In effect, the Internet has become the nervous system of modern society. Unfortunately, reliance on the Internet is a two-edged sword. While it provides tremendous benefits to states, it also opens them up to attack from state and nonstate actors. Given the ease with which anyone can acquire the tools necessary to conduct a cyber attack, anonymously and from afar, cyber attacks provide the enemies of a state with an ideal tool to wage asymmetric warfare against it. Thus, it should come as no surprise that states and terrorists are increasingly turning to cyber attacks to wage war against their enemies.

Today, the United States treats cyber attacks as a criminal matter and has foregone using active defenses to protect its critical information systems. This is a mistake. The government needs to modernize its approach to cyber attacks in order to adequately protect US critical information systems. Unless policymakers change course, the United States will continue to be at greater risk of a catastrophic cyber attack than need be the case.

Modernizing the US approach to cyber attacks requires major changes to the way the federal government currently does business.

First and foremost, the United States needs to start using active defenses to protect its critical information systems. This will better protect these systems, serve as a deterrent to attackers, and provide an impetus for other states to crack down on their hackers.

Second, the United States needs to devote significantly more resources and personnel to its cyber warfare forces. Creating the preeminent cyber warfare force is an absolute imperative in order to secure US critical infrastructure against cyber attacks, and to prevent the Internet from becoming the Achilles’ heel of the United States in the 21st century.

Furthermore, a large, expertly trained cyber warfare force should be a prerequisite to actually using active defenses, since using active defenses on the national scale without properly trained personnel could easily lead to unjustified damage against illegitimate targets.

The decision to use active defenses will, no doubt, create a lot of controversy, as would any major change to state practice. However, there is sound legal justification to use them, as long as their use is limited to attacks originating from sanctuary states, as laid out in Chapter 4. Limiting active defenses to attacks originating from sanctuary states still leaves states vulnerable to cyber attacks from rogue elements of cooperating states, but this change to state practice significantly improves US cyber defenses without running afoul of international law.

Furthermore, under a paradigm where active defenses are authorized against sanctuary states, the United States could feel comfortable knowing that either cyber attacks would be defended against with the best computer defenses available or that when computer defenses were limited to passive defenses alone, the state of origin would fully cooperate to hunt down and prosecute the attackers.

In adopting this approach, the United States needs to use its diplomatic influence to emphasize states’ duty to prevent cyber attacks, defined as passing stringent criminal laws, conducting vigorous law enforcement investigations, prosecuting attackers, and, during the investigation and prosecution, cooperating with the victim-states of cyber attacks. Using US influence to emphasize this duty, combined with the threat that the United States will respond to cyber attacks with active defenses when states violate this duty, should help coerce sanctuary states into taking action against their hackers. This is an essential step toward both a global culture of cyber security and eliminating the threat of cyber attacks from nonstate actors.

Admittedly, the decision to use active defenses is not without complications. Technological limitations will still make it difficult to detect, assess, and trace cyber attacks. As a result, frontline forces will run into trouble trying to factually assess attacks and, given the speed with which cyber attacks execute, will frequently be forced to make decisions with imperfect information. (These difficulties are assessed in greater detail in Chapter 4.) Thus it is imperative for the United States to invest the capital necessary to ensure that its cyber warfare forces are able to overcome these difficulties. Otherwise, poor decisions are likely to be made, and active defenses might accidentally be directed against allied states or used before the legal thresholds for their use are crossed.

At a time when cyber attacks threaten global security and states are scrambling to find ways to improve their cyber defenses, there is no reason to shield sanctuary states from the lawful use of active defenses, and every reason to enhance US defenses to cyber attacks by using them. Selectively targeting sanctuary states with active defenses will not only better protect the United States from cyber attacks but should also push other states to take cyber attacks seriously as a criminal matter because no state wants another state acting within its borders, even electronically.

Using force against other states may sound like a harsh measure, but states that wish to avoid being the targets of active defenses can easily do so; all they must do is fulfill their duty to prevent cyber attacks.

Lieutenant Commander Sklerov is a native of upstate New York. He received his Bachelor of Arts from the State University of New York at Binghamton, his Juris Doctorate from the University of Texas, and his Masters of Law in International and Operational Law from the US Army Judge Advocate General’s School. He is admitted to practice before the Texas Supreme Court, the US District Court for Southern Texas, the US Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces, and the US Supreme Court.

In June 2006, Lieutenant Commander Sklerov reported to USS NIMITZ as deputy command judge advocate. While on NIMITZ, he deployed twice and served as officer of the deck (Underway) during combat operations in support of OEF and OIF. He is currently stationed at Naval Base Kitsap Bangor in Silverdale, Washington, where he serves as the staff judge advocate for Submarine Groups NINE and TEN (also known as Submarine Group TRIDENT).

The following are fictional scenarios various government and private organizations come across for which there is insufficient legislation or frameworks to guide them in deciding on a proportionate response to cyber attacks.

With these scenarios I have provided a list of options for response, to assist in the creation of future legislation governing such responses. As of this writing, some of the options considered here are either not legal or may be legally questionable.

TeraBank, a financial institution with 5,000 employees, is forwarded a phishing email from 10 of their customers. The phishing attack prompts users to click on a Internet link to provide their online banking credentials and “validate their account.”

TeraBank contacts the Internet hosting provider of the phishing website linked to in the email and requests the website be taken down. The hosting provider will usually take down the phishing websites, but by the time that occurs, the phishers may have received hundreds of bank account credentials from TeraBank’s customers.

TeraBank forwards the email to other organizations, such as law enforcement. Law enforcement will recieve many of these phishing emails, and as they are constrained by national borders, they would most likely do nothing. Some organizations, such as Internet service providers, may respond to this phishing attack by blocking access to the phishing site for their customers.

TeraBank, using an automated computer program, enters information for hundreds of thousands of fake bank accounts in the phishing website. Although legally questionable, this approach would pollute the pool of valid banking credentials the senders of the phishing email would possess. It is likely that after attempting to use their harvested banking credentials with no success, the attackers would move onto launching phishing emails against another bank.

TeraBank contacts a “hacker for hire” and pays him to launch a distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack against the phishing website, making it inaccessible. Launching DDoS attacks typically are illegal in many countries. While TeraBank is financing an illegal act, this DDoS attack may impact the businesses of innocent parties, especially if their businesses are hosted on the same website as the phishing website.

Security researcher Fred Blinks discovers a website, http://www.secshare.com, that has been hacked and is hosting drive-by-download malicious software or malware, which means that any visitors to the website could potentially have their computers infected with malware.

Fred Blinks contacts the administrators of http://www.secshare.com, advising them about the malware being served on their website and the fact their website has been hacked.

Fred Blinks investigates the malware served on http://www.secshare.com further and discovers that it connects to http://mybotnethome.cn. Fred also notices that mybotnethome.cn provides statistics to the bot herder, such as from which website users were infected. Knowing this, Fred purposely infects a machine of his and inserts a piece of programming code into the section that the malware uses to tell the bot herder from which website the user was infected (in technical speak, this is known as the HTTP referrer).

This piece of programming code will cause the bot herder’s Internet browser to connect to Fred’s machine when the bot herder views the statistics of its bots, therefore providing Fred with the IP address of the bot herder.

Law enforcement official John Smith discovers that an online hacking and credit card bulletin board, http://www.ccmarket.ws, has been compromised and that the hacker has advertised her alias and front web page of the hacked bulletin board.

Knowing that obtaining a copy of the ccmarket bulletin board database would provide an enormous amount of information, John Smith, using the alias “da_man,” contacts the perpetrators of the www.ccmarket.ws compromise, asking if they would be willing to sell him a copy of the ccmarket database. This database would include information such as private messages, email addresses, and IP addresses. Here, John is financing a person who committed an illegal act.

Law enforcement official Michael McDonald has been investigating an online group that is involved with sharing child abuse material. Michael believes he has identified the alias of the person who is leading the group, but he is unsure where this person is geographically located. Michael knows that this person uses anonymous proxies to mask his IP address when on the Internet and is reasonably technical. Michael also knows that this person appears to be sexually abusing children and uploading images of his crimes onto the Internet.

Michael, in consultation with his technical people, decides that the only way to identify the leader of this online child exploitation group is to compromise his computer.

Michael’s technical people are able to successfully compromise the leader’s computer, providing them with information that can positively identify the leader and the leader’s whereabouts. Michael, who is based in the United States, now knows that the leader is based in Belarus and knows that his technical people may have broken the laws there.

Policymakers would be well-advised to consider these scenarios as realistic depictions of events that could and do occur in many nation-states. The only question is which option best addresses the interests of the state and its citizens, and the answer to that question is outside the scope of this submission.

This essay was written by an active duty member of an international law enforcement agency.

By Alexander Klimburg

The general public is often wholly unaware of how much of what we commonly call “security” depends on the work of informal groups and volunteer networks. For a while it seemed that Western governments had generally gotten the message: when most of your critical infrastructure is in private hands, it is natural that new forms of private-public partnerships need to be created to be able to work on critical infrastructure protection. Organizations such as the US ISAC (Information Sharing and Analysis Center) and the UK WARP (Warning, Advice, and Reporting Point) are examples of this thinking. Unfortunately, most governments have a hard time moving beyond the “two society” (government and business) model. In an age where even the “managing” bodies of the Internet (such as ICANN) do not belong to either of these groups but instead are really part of the “third society”—i.e., the civil society—this is a critical, and potentially fatal, omission. From groups of coders working on open source projects to the investigative journalism capability of blogs, the breadth of the involvement of the civil society and nonstate actors in cyber security is wide and growing. But what are these groups, exactly?

The variety of these groups is as wide as the Internet itself, and these groups also interact directly with the harder side of cyber security. Nongovernment forces of various descriptions have attacked countries on their own (e.g., Estonia, Lithuania) and defended them, helped wage a cyber war (e.g., Georgia), and sought to uncover government complicity in them. One can even argue that most of the cyber terror and cyber war activity seen over the last decade can be ascribed to various nonstate actors. A recent US Congressional inquiry heard that the great majority of the Chinese attacks against the United States were probably being done by young volunteer programmers whose connection with the security services was probably more accidental then anything else. Indeed, if one looks at the sum total of cyber security-relevant behavior, from software and patch development on the technical side to the freelance journalism and general activism on the political side (and with the “script kiddie patriot hackers” somewhere in between), it indeed seems that most “cyber security” work is done by members of the third society, with business following close behind—and government bringing up the rear.

Do these groups really have anything in common? After all, it is questionable whether heavily instrumentalized civilian hacker groups in China and Russia really qualify as representatives of a “civil society.” Should they really be compared to, say, a Linux developers’ group or an INFOSEC blog network? Aren’t these “patriot hackers” just an update of the age-old paradigm of the citizen militia and the flag-burning rent-a-mob, but with broadband?

Although the militia model can to a limited extent be applied to some of the Russian and Chinese groups (indeed, the Russians actively talk of the need to maintain an “information society” for their national security, and the Chinese have recruited an “information operations militia”), the model just does not hold for the many groups rooted in liberal democratic societies. This is particularly evident when examining nontechnical (i.e., not “White” or “Grey” hacker) groups and their activities. They are increasingly able to provide critical input into one of the most difficult aspects of any wide-scale cyber attack, namely attacker attribution.

Identifying the true actors behind a cyber attack is a notoriously difficult task. Attributing attacks to individual actors is traditionally seen as being the acid test to determine whether an attack is rated as an act of cyber war or an act of cyber terrorism (or even “cyber hooliganism”). Given these rather high standards, governments have been notoriously reluctant to point fingers. After all, there was no evidence that could be shared publicly. On the surface it seemed that the authoritarian governments of Russia and China had found the ultimate plausible-deniability foil with which to jab the West: rather then personally engaging in hostile cyber attacks, these governments could simply refer to the activities of their “engaged and active civil society” and wash their hands of the affair.

The advent of engaged civil society groups has changed this. Since 2005, these groups have published a flood of reports that have examined suspicious cyber behavior, mostly originating in Russia and China. The Georgian cyber attacks were particularly interesting, as the timing seemed to indicate at least some level of coordination between the Russian military’s kinetic attacks and the assault on Georgian servers. Reports such as those generated by Project Grey Goose helped to show that although the information of Russian government complicity in the cyber assault on Georgia was far from conclusive, there was much circumstantial evidence. For the reports, and the Western media that depended on them, this was sufficient. Unlike governments, for the public, “perfect” was clearly the enemy of the good.

The information in these reports is not good enough for cruise missiles, but it certainly is good enough for CNN. The barrage of reports that imply direct Russian government involvement has been widely reported in Western media. The increase of embarrassing questions posed to the Kremlin is probably a direct result of this media attention. At a cyber security conference at the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) in 2008, an American official privately remarked to me that the incessant accusations repeated in the media were leading the Kremlin to reduce its support of various groups, such as the pro-Putin Nashi, whose members have been implicated in cyber attacks. He directly credited the work of the civil society groups—including Grey Goose—in bringing this about. Sunlight as a disinfectant seems to work across borders as well.

It therefore appears that the best defense against a compromised or captive civil society is a free one. I have taken to referring to these “free” groups as security trust networks (STNs), and there are considerable differences between these groups and the ones that they often seem to work in direct opposition to:

An STN is independent and not beholden to any agency of government or private business. The state does not exert direct control over them, and cannot (easily) shut it down. This does not mean that the STN does not support a government; it just means that it chooses when and if to do so.

An STN is defined not only by the trust within the network itself but also the trust that other networks bring to it. For instance, an STN will often be seen as a credible partner for government and law enforcement, despite having no formal structure or pedigree.

STNs are defined by ethics: besides (generally) operating within the remits of the law, its members share a common moral code, explicit or implicit, based on “doing the right thing.” The shared moral mission of the STN is its official raison d’être.

Western governments often depend on these STNs much more than they realize. This is especially true for the technical experts, who invest a large amount of labor that mostly goes unnoticed, but also for the investigative STNs, such as Grey Goose, that certainly have helped frame the public debate.

So is it possible for a government to help create these STNs? The question is not as bizarre as it might seem. Russia has actively followed this course since at least 2000 (the publication date of its “Information Security Doctrine”) and is trying to “build a information society.” Although Alexis de Tocqueville might well wince at the idea of a government building a civil society, there is indeed much that truly democratic governments can do to encourage the formation of such groups and work together with them:

- Openness

Allowing government employees and security professionals to engage in social media (and blogging in particular) has been a contentious issue in the United States for years. A number of problems do arise from this type of behavior, quite a few of them security-related. Nonetheless, the possible benefits (such as the creation of an STN) can easily outweigh the real damage potential. The United States is far ahead here compared to most European governments, which still forbid this type of action.

- Communication

Organized outreach programs are vital. In the purely technical and purely diplomatic circles, this is an established practice, but it should extend to other security areas as well. Again the United States has gone far in this area, with experiments with crowdsourcing intelligence and the like, but Australia and the UK also have very engaging approaches.

- Accessibility

Being available for queries outside of the normal process is an important sign of truly open government. This means not only working across government (“Whole of Government”) but also being prepared to collaborate and communicate with nongovernment organizations (“Whole of Nation”). Although everyone needs to improve here, the United States has an especially long way to go.

- Transparency

This is often misunderstood as demanding transparency on the inner workings of government. Instead, it is the government’s goals that should be transparent—which they should continuously be forced to defend—in part for the STNs that might be able to indicate where the government is, once again, working against its own goals. The United States does well here, although some European countries, such as the UK, Holland, and Sweden, are at least as transparent.

- Understanding ambiguity

This is always an important skill, and it is important that individual civil servants understand the different roles people can occupy, and to what extent these roles facilitate or hinder closer cooperation. This is particularly important when someone’s motivation is balanced between altruistic volunteerism and commercial opportunity-seeking. A mixed experience for the United States (the “revolving door”), but the UK traditionally has been a past master at this art.

- Trust

Trust makes security stronger, and it needs to work on every level. Security clearances are for the most part unreconstructed affairs dating back to the dawn of the Cold War. In the end, often they don’t mean much—whether you get information will still depend on the level of trust available. Obviously certain basic background checks are logical and should be done if any real security info is going to be passed onto outsiders; however, these are a couple of levels below real security clearances and can stay that way. Trusting one’s own judgment is much more important. The United States can learn much about this from some European countries, especially the UK.

It is not an exaggeration to claim that an independent, vibrant, and engaged civil society is one of the unique indicators of a liberal democracy. The fact that they are a benefit, not a cost, is most evident in security trust networks. Democratic governments would do well to support them as a centerpiece in Whole of Nation cyber security.

Alexander Klimburg is a Fellow at the Austrian Institute for International Affairs. Since joining the Institute in October 2006, he has worked on a number of government national security research projects. Alexander has partaken in international and inter-governmental discussions, and he acts as a scientific advisor on cyber security to the Austrian delegation to the OSCE as well as other bodies. He is regularly consulted by national and international media as well as private businesses.

[40] The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Defense.