By Ned Moran[39]

The United States currently faces the daunting challenge of identifying the actors responsible for launching politically motivated cyber attacks. According to Defense Secretary Robert Gates, the United States is “under cyber attack virtually all the time, every day.” It is estimated that more than 140 countries currently field cyber warfare capabilities. Additionally, sophisticated adversaries can route attacks through proxies and obfuscate their identities. These facts combine to make attribution of cyber attacks a difficult challenge.

During the Cold War, none of these challenges existed. Attacks between the United States and rival powers were few and far between. The pool of nuclear powers was limited to an exclusive club. Additionally, it was more difficult to route a nuclear attack through a proxy.

The heightened ability to detect and identify the source of nuclear or missile attack increased stability during the Cold War. Many policymakers fear that the current inability to quickly and accurately identify the source of a cyber attack leads to instability and increases the chances that cyber attacks will be carried out. In order to improve its defensive posture, the United States must develop a cyber attack early warning system.

Although a number of private companies and nonprofit organizations have constructed a cyber infrastructure designed to detect cyber attacks, these infrastructures do little to provide adequate early warning for a politically motivated cyber attack.

Additional technical solutions will not adequately solve the problem of building an early warning capability for detecting politically motivated cyber attacks. Instead, a fresh analytical framework is needed. This framework will help limit the pool of possible aggressors and allow policymakers to marry whatever technical evidence can be gathered during a cyber attack with a list of possible aggressors. Ideally, the output of this analysis will be the identification of the actor responsible for a cyber attack.

More importantly, this framework should allow defenders to predict rather than react to the occurrence of politically motivated attacks. The current cyber early warning systems that track scans and probes cannot provide the same predictive capability as the proposed model. The current cyber early warning system does not sort signals from noise and instead reports on all perceived malicious scans and probes. The model discussed in the following section will allow defenders to predict when a cyber attack will occur and which actors are likely to initiate the attack.

A careful review of numerous politically motivated cyber attacks reveals a consistent pattern in how they are organized and executed. Previous attacks, whether executed by nonstate or state actors, appear to be grounded in latent political tensions between adversaries. As these latent tensions heat up, cyber aggressors tend to carry out cyber reconnaissance probes in an apparent effort to prepare for future attacks. Latent tensions require some type of initiating event that can be used to mobilize cyber patriots into a cyber militia. The cyber militia can be used to carry out brute-force attacks, while more elite hackers can use the intelligence gathered from prior cyber reconnaissance probes to execute more sophisticated attacks (Figure 12-1).

Although still dominated by nation-states, today’s international political system features a number of players. Nonstate actors—such as terrorist groups, international organizations, and in some cases ideologically affiliated flash mobs—have exercised some measure of geopolitical influence.

It is therefore important to test the proposed model of the stages of politically motivated cyber attacks against both state and nonstate actors. The model must be equally useful in predicting a cyber attack originating from either a state or nonstate actor against either a state or a nonstate actor.

Latent tensions exist in the background between any number of actors in the international political system. For example, historical animosity between Muslims and the state of Israel have resulted in a steady state of politically motivated attacks—both in the physical world and in cyberspace. Under the right conditions, these latent tensions can explode into full-fledged warfare.

Against this simmering backdrop, tensions can at times boil over. However, prior to the initiation of hostilities in cyberspace, adversaries are likely to conduct probes of each other’s infrastructure. The rationale for conducting cyber reconnaissance is no different than the rationale for conducting reconnaissance in the physical world. Adversaries conduct cyber reconnaissance in an effort to discover vulnerabilities in their rival’s infrastructure that can be exploited if and when tensions erupt into hostilities. Cyber reconnaissance also allows adversaries to develop effective tools specifically designed to attack an enemy’s infrastructure.

During the August 2008 war between Russia and Georgia in the disputed region of South Ossetia, a parallel conflict occurred in cyberspace. Investigations by Project Grey Goose researchers found that pro-Russian hackers conducted in-depth cyber reconnaissance prior to the initiation of hostilities on August 8, 2008. Specifically, Georgian websites were probed for vulnerabilities. The US Cyber Consequence Unit (USCCU) later confirmed these findings. In a report on the cyber conflict in Georgia, the USCCU wrote:

[W]hen the cyber attacks began, they did not involve any reconnaissance or mapping stage, but jumped directly to the sort of packets that were best suited to jamming the websites under attack. This indicates that the necessary reconnaissance and the writing of attack scripts had to have been done in advance. Many of the actions the attackers carried out, such as registering new domain names and putting up new websites, were accomplished so quickly that all of the steps had to have been prepared earlier.

Initiating events are any events that cause latent tensions to boil over and trigger politically motivated attacks. Just as the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand put countries aligned with Austria-Hungary onto a collision course with countries aligned with Serbia and eventually led to World War I, similar initiating events have led to the outbreak of politically motivated cyber attacks.

The 2007 Cyber War against Estonian websites took place against the backdrop of simmering tensions between Estonia and Russia. Tensions between Estonia and Russia are primarily a result of the Soviet Union’s annexation of the Baltic nation-state in 1940 at the start of World War II. Following this annexation the Soviet Union initiated a crackdown, arresting more than 8,000 Estonian citizens and executing an additional 2,000 citizens.

The proximate cause for the cyber attacks on Estonia was the Estonian government’s decision to relocate a Soviet Red Army war memorial from central Tallinn, the Estonian capital city. Many Estonians see the memorial as a stark reminder of the former Soviet Union’s “occupation” of Estonia, whereas many Russians view the statue as a memorial to the Red Army’s sacrifices in its liberation of Estonia from Nazi Germany.

In the immediate aftermath of the statue’s relocation, angry youths with links to the Kremlin rioted around the Estonian Embassy in Moscow. Russian officials also insisted that the statue be returned to its original location, and in an unprecedented move, demanded that the current Estonian government resign. These riots in the physical world were paralleled by a corresponding campaign of digital violence.

According to Adam Elkus, cyber mobilization “is a process of massing force against decisive points” (http://www.groupintel.com/2009/02/13/the-rise-of-cyber-mobilization/). The aggrieved actor uses the initiating event to incite patriotic hackers into action.

Examples of cyber mobilization abound. Chinese patriotic hackers have traditionally rallied support to their cause via various online message boards and chat rooms. In 2008, Chinese citizens created the Anti-CNN web forum in response to “the lies and distortions of facts from the Western media.” Chinese citizens and patriotic hackers believed the Western media unfairly criticized China’s treatment of Tibetan people. Although the creation of the Anti-CNN forum and the mobilization of Chinese patriotic hackers against Western media companies did not result in any successful high-profile attacks against Western media websites, the Anti-CNN forum was able to mobilize a number of Chinese citizens in its efforts to counter perceived biases in Western media coverage. In April 2008, shortly after the web forum launched, the website claimed to receive 500,000 visits per day.

Politically motivated cyber attacks range in sophistication from small-scale denial of service attacks to well-organized and stealthy espionage attacks. The sophistication of a cyber attack is dependent on the skill of attackers and the amount of reconnaissance performed prior to the attack. A sophisticated attacker aided with intelligence gathered from reconnaissance can execute a devastating attack, whereas an unsophisticated attacker without any intelligence on its targets will be relegated to simple brute-force attacks.

A deeper understanding of this model can be achieved by analyzing previous politically motivated cyber attacks. To fully test the utility of this model, it is important to study previous cyber wars between nation-states, cyber attacks by nation-states against nonstate actors, and cyber attacks by nonstate actors against nation-states.

Latent political tensions between Russia and Georgia existed prior to the breakup of the Soviet Union. In the late 1980s, Georgian opposition leaders pressed for independence from the Soviet Union. In 1989, Abkhaz nationalists demanded the creation of a separate Soviet republic. This demand led to conflicts between ethnic Georgians living in Abkhaz and Abkhaz nationalists supported by the Soviet Union.

After the breakup of the Soviet Union, tensions in Abkhaz continued to rise. In 1992, Abkhaz nationalists continued to press for independence, and militants attacked government buildings in Sukhumi. In response, Georgian police and National Guard units were sent into Abkhaz to regain control. The tensions between Georgia and Russia over Abkhaz have continued to the present day and were largely responsible for the outbreak of conflict in the South Ossetia region in 2008.

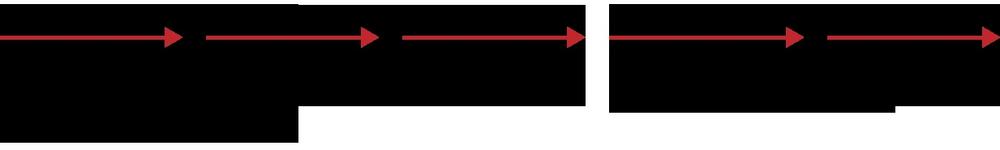

The outbreak of conflict in South Ossetia in 2008 was paralleled by the outbreak of cyber attacks against Georgian government websites (Figure 12-2). Pro-Russian hackers promoted attacking Georgian websites and coordinated their actions via a network of hacking websites frequented by Russian cyber criminals and hackers. Additionally, suspected pro-Russian hackers launched StopGeorgia.ru, a website dedicated to recruiting sympathetic hackers to the Russian cyber militia. StopGeorgia.ru provided eager sympathizers with a list of Georgia websites to attack, as well as instructions on how to launch various kinds of cyber attacks. Georgian websites were either defaced with anti-Georgian propaganda (Figure 12-3) or were knocked offline with distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks.

According to the Information Warfare Monitor’s “Tracking GhostNet: Investigating a Cyber Espionage Network” report, “accusations of Chinese cyber war being waged against the Tibetan community have been commonplace for the last several years. The Chinese government has been accused of orchestrating and encouraging such activity as part of a wider strategy to crack down on dissident groups and subversive activity.”

During their investigations, the Information Warfare Monitor team found evidence of an extensive cyber espionage network that targeted the Tibetan community as well as other groups. The cyber espionage network was composed of “at least 1,295 computers in 103 countries, of which close to 30% can be considered high-value diplomatic, political, economic, and military targets.” Further, the Information Warfare Monitor found “documented evidence of GhostNet penetration of computer systems containing sensitive and secret information at the private offices of the Dalai Lama and other Tibetan targets.”

The cyber espionage attacks against the Tibetan community were carried against the backdrop of political tensions between the Chinese government and the Tibetan community (Figure 12-4). Tensions between these two groups escalated prior to the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics. The Chinese government was increasingly concerned that pro-Tibetan independence groups planned to use the Summer Olympics as a platform to protest and attract increased international attention. Although cyber espionage attacks occurred well before the Chinese government became concerned about the possibility of Tibetan protests during the Beijing Games, it is likely that the increased tension between the Chinese and the Tibetans during this time period was a driver of increased cyber espionage attacks against the Tibetan community. It is unclear who carried these attacks, but it is likely that the Chinese government received the information collected from these efforts.

The Chinese hacker community communicates primarily through a series of web forums and chat rooms. Hacking attacks are promoted on these websites, and often calls to action against specific targets are posted. In the case of the GhostNet attacks, rallying the Chinese cyber militia against specific targets would have been counterproductive due to the semi-public nature of these websites. If the targets of cyber espionage attacks are openly posted, it is more likely that the target will be informed of its status as a target and therefore increase its defensive posture. Instead of following the Russian cyber militia’s example of openly mobilizing sympathetic hackers for attacks against Georgian targets via the StopGeorgia.ru forum, the Chinese militia was mobilized for the cyber espionage campaign against the Tibetan community through a more nuanced approach.

This more nuanced approach included general discussion about enemies of the Chinese people. Just as the Chinese cyber militia used the Anti-CNN website to rail against the perceived bias of the Western media, discussions on various Chinese hacker and other nationalist websites included discussions about the need to reign in the Tibetan community. No direct discussion about targeting specific Tibetan organizations was required. Instead, the general discussion regarding the increasingly restive Tibetan community likely was enough to motivate members of the Chinese cyber militia to execute cyber espionage attacks such as the example shown in Figure 12-5.

On September 30, 2005 the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten published a series of cartoons depicting the Prophet Mohammed. The newspaper claimed it published these cartoons as an attempt to contribute to the ongoing debate about self-censorship and the ability to criticize Islam.

Danish Muslim organizations sternly objected to the publication of the cartoons and held public protests to voice their displeasure. Protests soon spread around the world. The following February, protest against the publication of the cartoons continued and a corresponding campaign of website defacements and denial of service attacks were launched.

According to zone-h, a European consortium of IT security professionals that tracks cyber crime, over 600 Danish websites have been attacked. A majority of these attacks were website defacements; however, denial of service attacks against the Jyllands-Posten newspaper website (http://www.jp.dk) were also executed.

The Prophet Mohammed cartoon controversy occurred against the backdrop of simmering tensions between European countries and Muslims (Figure 12-6). In the case of these attacks, very little cyber reconnaissance was required. Attackers understood that websites in the .dk domain were to be targeted. Many of the website defacements appear to have been carried out with automated scripts designed to exploit known vulnerabilities in production web server software.

Although the cyber attacks occurred many months after the publication of the cartoons, it is clear that these cartoons were used as the initiating event to rally Muslim and other sympathetic hackers to the cause of attacking Danish websites. These defacement and denial of service attacks were coordinated through a network of jihadist websites. Defaced sites also included propaganda designed in part to promote further attacks against Danish websites. Additionally, individuals promoting the boycott of Danish goods launched no4Denmark.com. Although this particular website was not used to organize the Muslim cyber militia, it certainly drew attention to their cause.

Latent tensions and cyber reconnaissance are important stages in well-organized politically motivated cyber attacks, but they do not appear to be necessary. The low-cost and low-risk nature of cyber warfare allows an attacker to quickly coordinate an attack against an adversary. Latent tensions are not necessary as long as an initiating event capable of rallying a cyber militia to action occurs. A cyber militia can conduct an unsophisticated brute-force denial of service attack without conducting the type of extensive cyber reconnaissance necessary to execute a sophisticated cyber attack. The only reconnaissance required to conduct an unsophisticated brute-force denial of service attack is the simple list of targeted websites. However, these types of attacks are easier to defend against and therefore should not preoccupy US policymakers.

Instead, policymakers should focus on those cyber attacks executed by adversaries with preexisting grievances against the United States. These latent political tensions encourage an attacker’s cyber militia to conduct detailed cyber reconnaissance as well as rally sophisticated hackers to join the attacker’s cyber militia.

This model could also be used to distinguish between cyber crime attacks and politically motivated attacks. Sophisticated politically motivated cyber attacks will follow the 5-stage model set forth earlier in this chapter: latent tensions, cyber reconnaissance, initiating events, cyber mobilization, and cyber attack. Unsophisticated politically motivated cyber attacks will follow a truncated 3-stage model of initiating event, cyber mobilization, and cyber attack.

In contrast, cyber crime attacks are more likely to follow an altered 2-stage model: cyber reconnaissance and cyber attack. If no latent tensions exist between adversaries, no obvious initiating event occurs, and no mobilization of cyber militia is detected, then criminal organizations motivated by financial gain are likely responsible for the attacks in question.

The true value of this model is two-fold. From a proactive perspective, this model shows us that well-organized and sophisticated politically motivated cyber attacks are likely to involve some public or semipublic form of cyber mobilization. Cyber militias are likely to rally other sympathetic hackers to their cause via online chat rooms and message boards. These calls to arms are typically announced via public or semipublic channels because cyber militias are typically interested in rallying a large number of hackers to their cause. As more hackers join the cyber militia, the power of the militia increases in terms of its ability to generate more bandwidth during a distributed denial of service attack. Additionally, as more hackers join a cyber militia, more noise is generated and defenders will have a harder time detecting truly malicious attacks from the more benign brute-force denial of service attacks. Fortunately for the defenders, as cyber militias attempt to rally more hackers to their cause, their public or semipublic communications can be intercepted. A proactive defender can intercept a cyber militia’s call to arms and construct an informed defensive posture.

From a reactive perspective, use of this model could aid in assigning attribution for a cyber attack. As discussed, a sophisticated politically motivated cyber attack is likely to occur against the backdrop of latent political tensions between adversaries. As actors within the international arena are likely to have adversarial relations with only a limited number of actors, that pool of possible attackers is limited. The pool of possible attackers is further limited to those actors that have previously demonstrated both the capability and intent to conduct sophisticated cyber attacks.

The proposed 5-stage framework of politically motivated cyber attacks can be used to create a Defense Readiness Condition (DEFCON) for cyberspace. The existing DEFCON scale, from 5 to 1, measures the readiness level of the US armed forces. DEFCON 5 represents normal peacetime military readiness, whereas DEFCON 1 represents maximum readiness and is reserved for imminent or ongoing attacks against the United States.

The 5-stage model also could be used to inform the United State’s DEFCON rating for cyberspace. Cyber DEFCON 5 exists during normal conditions with latent political tensions between the United States and a range of adversaries.

Cyber DEFCON 4 could be activated when cyber reconnaissance is detected against the backdrop of existing latent political tensions between the United States and its adversaries. For example, when probes are detected from Russia, China, or other adversaries with a demonstrated cyber warfare capability and a declared intention, DEFCON 4 should be activated.

Cyber DEFCON 3 could be activated in the aftermath of cyber reconnaissance and an initiating event. For example, in the aftermath of the US-China spy plane incident in 2001, when a US Navy EP-3 surveillance aircraft collided with a People’s Liberation Army fighter plane. This incident sparked a cyber war between US and Chinese hackers, during which a number of US and Chinese websites were defaced or knocked offline.

Cyber DEFCON 2 could be activated after an initiating event occurs and the mobilization of enemy cyber militias is detected. In the aftermath of the invasion of South Ossetia, pro-Russian hackers launched the StopGeorgia.ru website in order to mobilize a pro-Russian cyber militia. As previously discussed, cyber mobilization typically occurs in semipublic forums because militia organizers desire to attract as many sympathetic hackers as possible. The more public the call to arms, the greater the chance the militia will recruit new members and increase in size. Fortunately, the more public the call to arms, the greater the likelihood that the defender will detect the mobilization of the enemy’s cyber militia. When these types of activities are detected, cyber DEFCON 2 should be activated.

Cyber DEFCON 1 should be activated when attacks appear imminent or are ongoing. It is apparent that cyber attacks will be used either in parallel with armed attacks or as the sole means of attack between adversaries. Therefore, it is important to understand how attacks are planned, organized, and executed.

Use of this model may improve the ability of the United States to predict and defend against future politically motivated cyber attacks. It is therefore important that this 5-stage model be discussed, tested, and altered as necessary.

[39] Ned Moran is a senior intelligence analyst for a well-known systems integrator, an adjunct professor in intelligence studies at Georgetown University, and a valued member of Project Grey Goose.

Originally Ned invited me to coauthor this paper for publication elsewhere, but due to my time limitations and the innovative nature of Ned’s proposed model of predicting cyber attacks, I asked if he would consent to having it published here first. He graciously agreed, and I think the book is richer for it.