Card: I need guarantees.

Card: what if you change the pass and don’t give any info? I’ve been on the *** several years now. It’s a resource for carders.

7: I know, I am on there, too.

7: if you take my info into account and work a little, you can get a lot more money.

Card: I see.

7: I just think it’s a pretty dangerous thing—there are some big guys behind this money—they don’t ask who you are and why you are doing this. They’ll just break both your arms.

Whether you think the Russian mafia or the Chinese Triads are involved in cyber attacks really depends on how closely you align cyber crime with other forms of cyber conflict. As I stated earlier, I believe that no such distinction should exist. Cyber crime is perpetrated by an attack on a network, just as is done in acts of cyber espionage or computer network exploitation (CNE). The malware used to gain access to backend databases is the same. In many cases, the same hackers are involved in cyber crime and geopolitical attacks on foreign government websites, as is the case with one of the two hackers quoted above.

The hacker identified as “7” was also a member of the StopGeorgia.ru forum, albeit under a different alias, and directly participated in attacks on Georgian government websites. 7 is also the one who inferred the involvement of the Russian mafia in underground cyber transactions such as the one from which that quote came (i.e., “...there are some big guys behind this money—they don’t ask who you are and why you are doing this. They’ll just break both your arms.”).

Assassination in the Russian Federation is a very real threat, and US intelligence agencies believe that elements of Russian organized crime have infiltrated the police force. That is why, the argument goes, so many assassinations remain unsolved.

US law enforcement and intelligence agencies have been investigating Russian organized crime since the 1990s. According to one of my contact’s at one of the three-letter agencies, they were making some excellent progress in establishing links between members of organized crime and Russia’s political leadership.

Once 9/11 happened, that research was halted, as everyone was transferred to counter-terrorism, which pretty much dominated things until 2007.

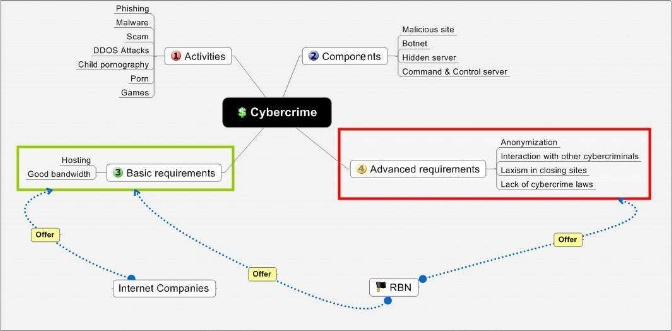

2007 was the year that the Russian Business Network (RBN) rose to prominence as a high-profit, low-risk criminal enterprise selling “bulletproof” services to anyone willing to pay its fee. Its business model of earning high profits with almost zero risk of being caught made the RBN the darling of the Russian underworld.

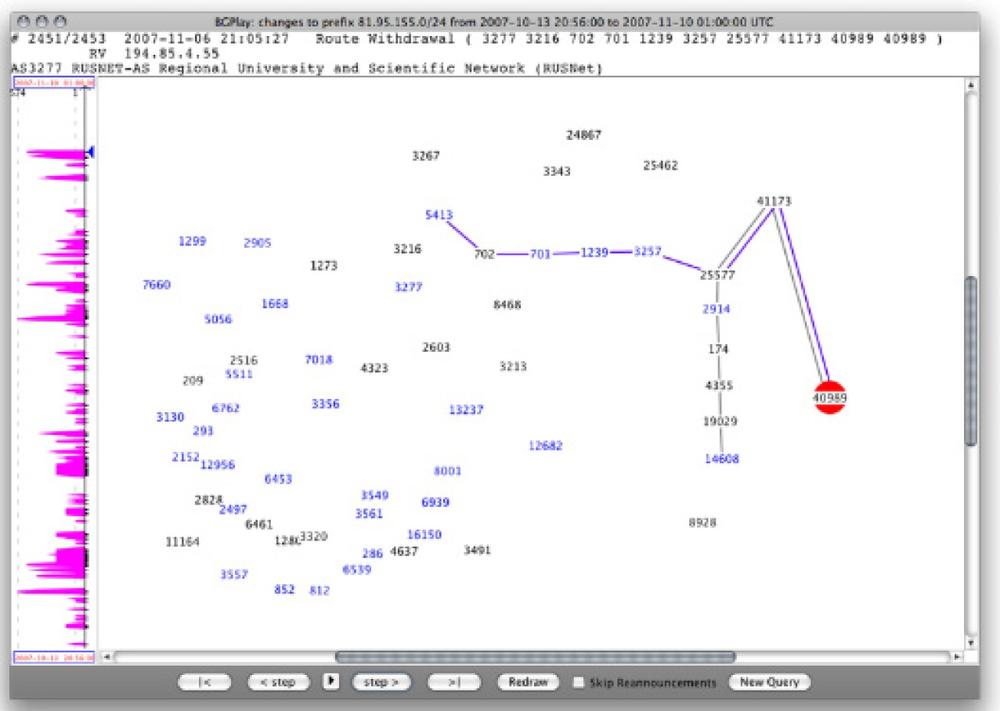

Then, in November 2007, the RBN seemed to vanish (Figure 8-1).

One thing that organized crime has always shied away from is the spotlight of media attention, and the RBN was getting a lot of it. One of the reporters responsible for penning story after story on their antics was Brian Krebs of the Washington Post. On October 13, 2007, three separate articles appeared on the Post’s Security Fix blog, written by Krebs.

Krebs’s first article appeared in the main section of the Post, where he described the role of the RBN as a criminal services provider, referring to at what the time were recently published reports from Internet security firms Verisign, Symantec, and SecureWorks.

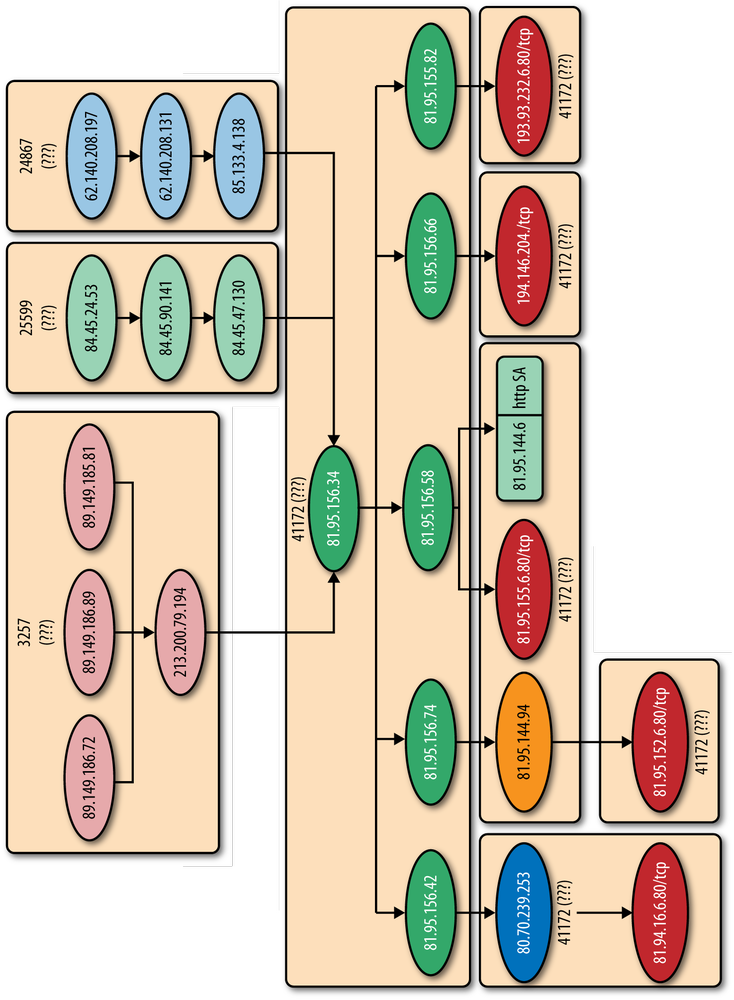

In a follow-up article on the Security Fix blog, Krebs went into much more detail, naming the upstream providers that the RBN relied on to provide its Internet connectivity: Tiscali.uk, SBT Telecom, Aki Mon Telecom, and Nevacon LTD (Figure 8-2).

He also traced its history back to 2004, when it was known as “Too Coin Software” and “Value Dot,” and then walked his readers forward to its present iteration:

Nearly every major advancement in computer viruses or worms over the past two years has emanated from or sent stolen consumer data back to servers at RBN, including such notable pieces of malware as Gozi (http://www.secureworks.com/research/threats/gozi/?threat=gozi), Grab, Haxdoor (http://www.f-secure.com/v-descs/haxdoor.shtml), Metaphisher (http://research.sunbelt-software.com/threatdisplay.aspx?name=PWS-Banker&threatid=41413), Mpack (http://blog.washingtonpost.com/securityfix/2007/06/the_mother_of_all_exploits_1.html), Ordergun (http://www.symantec.com/enterprise/security_response/weblog/2006/11/handling_todays_tough_security.html), Pinch (http://pandalabs.pandasecurity.com/archive/PINCH_2C00_-THE-TROJAN-CREATOR.aspx), Rustock, Snatch, Torpig (http://www.sophos.com/virusinfo/analyses/trojtorpiga.html), and URsnif (http://www.ca.com/us/securityadvisor/virusinfo/virus.aspx?id=58752). The price for these malware products often includes software support, and usually some virus writers guarantee that the custom version created for the buyer will evade detection by anti-virus products for some period of time.

David Bizeul is a French security researcher who has written one of the best reports on the RBN to date (see Figure 8-3). He summed up its business focus quite succinctly:

The RBN offers a complete infrastructure to achieve malicious activities. It is a cyber crime service provider. Whatever the activity is—phishing, malware hosting, gambling, pornography...the RBN will offer the convenient solution to fulfill it.

In any attempt to understand the influence of Russian organized crime in the cyber threat domain, a key distinction must be made between organized crime in Russia and elsewhere.

In the United States, the FBI and other agencies focus on how criminals may be infiltrating or, at the very least, influencing government offices. In Russia, the government infiltrates organized crime and establishes a reciprocal business relationship. The government provides protection in exchange for favors. Favors may range from making money to using a gang to implement state interests.

Richard Palmer made a similar case in his testimony before the House Banking Committee (September 21, 1999), wherein he explained how Russia is governed by the rule of “understandings” rather than the rule of law. According to Palmer, who spent 11 years with the Directorate of Operations at CIA, businesses operating inside the Russian Federation quickly learn that when it comes to collecting on bad debts or enforcing contracts, it’s faster and cheaper to engage Russian criminals than wait for the Russian court system to take care of it. Unfortunately, the flip side of that equation is also true: it’s sometimes cheaper to have the person you owe money to killed than to repay a debt.

In the case of the RBN, once media attention became frequent enough, the FBI sent several officials to Moscow to meet with its counterparts in the Federal Security Service (FSB). The purpose of the meeting was to share information about the criminal activities of certain individuals associated with the RBN and how the Kremlin might want to remove such a presence from the Russian Internet. The Russian security officers excused themselves, and when they returned approximately a half hour later, they informed the FBI officials that they must be mistaken, that no such domains existed on RuNet.

Back at the US embassy in Moscow, the FBI discovered that the more public domains formerly associated with the RBN had been migrated to new IP addresses.

That’s why it appeared that the RBN suddenly dropped from view. In reality it never went away; it just slipped back under the radar, away from any further media spotlight.

Tell Krebs nice job on Atrivo, but if he’s thinking of doing McColo next, he’s pushing his luck.

Investigating the Russian mob is one thing, but when an investigation may hurt profits, that’s another, much more dangerous matter entirely. Shortly after his September 2008 coverage of Atrivo, Krebs received the aforementioned anonymous threat.

Atrivo is an interesting case study for this book because it illustrates one of the problems yet to be addressed in cyber conflicts. What happens when a country is being attacked by malware that sits on a server within its own borders?

Atrivo, also known as Intercage, was a Concord, CA-based company that specialized in providing networks for spammers and other bad actors to use, many of which were associated with the Russian Business Network.

The RBN relied heavily on two networks hosted by Atrivo: UkrTeleGroup, which routed traffic through the Ukraine; and HostFresh, which routed traffic through Hong Kong and China.

A report by iDefense named Atrivo as having the highest concentration of malicious activity of any hosting company in the world.

Thanks to the concentrated efforts of independent researchers such as Jart Armin and James McQuaid, as well as Brian Krebs’s reporting of their work, Atrivo was dropped by its upstream providers and was effectively put out of business on September 22, 2008.

Not everyone was happy with the process used. Marcus Sachs, director of the SANS Internet Storm Center, wrote to Brian Krebs in an email, “There are others out there who need to be cut off but we’ve got to find a better way to do it than by creating the virtual equivalent of a lynch mob.”

Paul Ferguson of Trend Micro disagreed with Sachs and said that “this was a (good) example of the community policing itself.”

Atrivo’s biggest customer was the Estonian company ESTDomains, based in Tartu, Estonia (but registered as a US corporation in Delaware).

ESTDomains, as its name suggests, was a domain registrar that dealt almost exclusively with criminal elements engaged in setting up Internet scams. The principal of ESTDomains is Vladimir Tsastsin, who was convicted for credit card fraud, document forgery, and money laundering, and spent three years in an Estonian prison.

Krebs wrote a Security Fix blog post about Tsastsin and ESTDomains on September 8, 2008, wherein he quotes the head of Estonia’s Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT), Hillar Aarelaid:

To understand EstDomains, one needs to understand the role of organized crime and the investments coming from that, their relations to hosting providers in Western nations and the criminals who ply their trade through these services.

In other words, Tsastsin is one of the front men for Russian organized crime’s entree into the lucrative world of Internet crime. Two months after Krebs’s article outed him, ICANN pulled the plug on the right of ESTDomains to issue domain names, citing its CEO’s criminal conviction as the cause.

The McColo story is even more instructive for cyber-conflict policymakers than Atrivo/Intercage. It perfectly illustrates the key role that US-based businesses play in providing protected platforms for Russian organized crime enterprises that, in turn, are utilized as attack platforms by nonstate actors in nationalistic and religious actions.

McColo was formed by a 19-year-old Russian hacker and college student named Nikolai, aka Kolya McColo. Upon his death in a car accident in Moscow in September, 2007, the McColo company was taken over by McColo’s friend “Jux,” a “carder” (carders make their money in the underground market for stolen credit card data). The amount of money being made by McColo makes it likely that it attracted the attention of Russian mobsters, which puts an entirely new spin on the possible cause for Kolya McColo’s car accident.

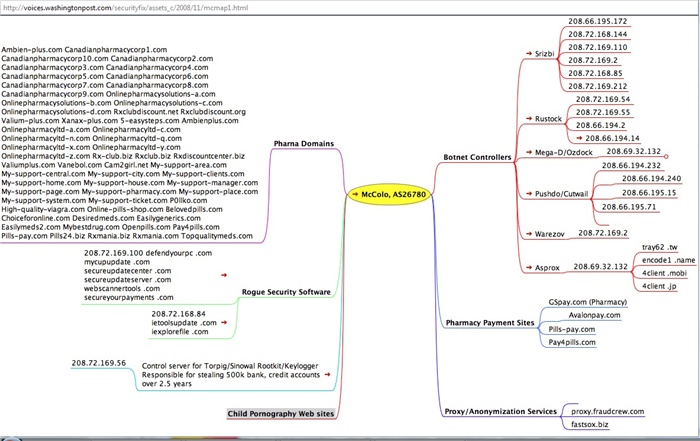

The graphic in Figure 8-4, created by Brian Krebs, illustrates the extremely broad scope of McColo’s collection of botnets and bad hosts in terms of spam and cyber crime. The following is Krebs’s explanation of what the graphic depicts:

The upper right-hand section of the graphic highlights the numeric Internet addresses assigned to McColo that experts, such as Joe Stewart, the director of malware research for Atlanta-based SecureWorks, say were used by some of the most active and notorious spam-spewing botnets—agglomerations of millions of hacked PCs that were collectively responsible for sending more than 75 percent of the world’s spam on any given day (for that sourcing, see the colorful pie chart at below, which is internet security firm Marshal.com’s current view of the share of spam attributed to the top botnets). In the upper left corner of the flow chart are dozens of fake pharmacy domains that were hosted by McColo.

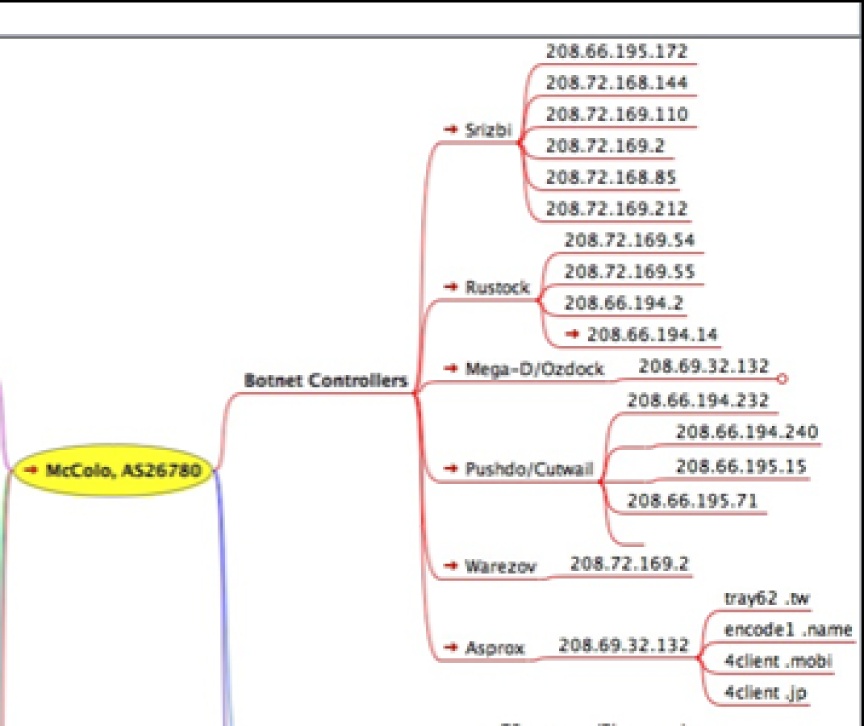

Figure 8-5 shows an expanded view of the upper-right corner of this graphic, which lists the botnet command and control servers (C&C) hosted on networks provided by McColo. It controls the world’s largest botnets, which collectively run millions of infected hosts (individual computers infected by malware) that generate an estimated 75% of the world’s spam according to TraceLabs, a division of the UK security firm Marshall.

When McColo was de-peered (i.e., dropped by its Internet backbone providers, Global Crossing, Hurricane Electric, and Telia), worldwide spam rates dropped by 67% overnight.

According to the FBI, US losses to Internet crime in 2008 amounted to $246.6 million. Since spam is the principal source of income for cyber criminals, McColo going offline represented a significant loss of revenue to criminal organizations, but it didn’t last long.

The authors of the botnets simply found other bandwidth resellers to take McColo’s place. In fact, the entire issue of unvetted bandwidth reselling represents a serious national security risk that must be addressed if nations want to begin to stem the tide of distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks generated by botnets against their websites. This is particularly true for the US government.

David Satter is a recognized authority on Russian organized crime, and I highly recommend his book Darkness at Dawn (Yale University Press).

Satter recently wrote an article on the suspected ties between Russian organized crime and the Russian police as seen in the rising unsolved murder rate of journalists in the Russian Federation whose work had become too problematic for the authorities to manage (“Who Murdered These Russian Journalists?,” Forbes.com, December 26, 2008). Satter used the case of the murdered journalist Anna Politkovskaya to illustrate his point.

He tells how Sergei Sokolov, Russia’s best-known investigative reporter and deputy editor for Novaya Gazeta (Anna’s former employer), testified how one of the accused men in her murder was an FSB agent who was ordered to follow Anna.

Charges related to planning the reporter’s murder were also brought against a former major in a police unit whose job it was to fight organized crime.

That same major was charged four years earlier with the torture and kidnapping of a Russian businessman. His reported accomplice was a former FSB colonel.

On February 19, 2009, the trial ended with no convictions. One month earlier, on January 19, Stanislav Markelov, Anna Politkovskaya’s lawyer, was shot to death as he left a news conference located less than half a mile from the Kremlin. No one has been charged with his murder.

There is a lengthy list of unsolved murders of journalists, businessmen, political opponents, and other figures over the past few years that should make anyone who envisions taking on organized crime reconsider.

The relevance of this broad look at Russian organized crime in a book about cyber warfare is to help establish a better understanding of the relationship between these criminal organizations and Russian government officials. That relationship doesn’t change because the landscape moves from the streets of Moscow to the virtual world of the Internet. Cyberspace simply becomes another domain in which organized crime can operate with the same ruthlessness and violence that they do elsewhere.

Understanding this is vital for Western government policymakers who may still believe that cyber wars are being fought by bored teenage hackers.

The links between Russian organized crime, Russian intelligence, and the Russian government are fairly well documented, but its extension into cyber crime is not. Affected governments need to conduct additional investigations into this problem and coordinate assets.