Adding other government and corporate bonds

The main focus of this book has been on creating a simple, yet powerful and robust portfolio for the rational investor. The message is hopefully clear: find your minimal risk asset and combine it with the broadest possible, yet cheaply acquired equity index, preferably one representing world equities. Do so in proportions that suit your desired risk profile and in a tax efficient way (see Chapter 11). If you do this and read no further, in my view you are already doing better than the vast majority of investors, private or institutional.

This chapter slightly muddies the waters for those investors who are willing to accept a bit more complexity, namely the addition of other government and corporate bonds. The addition of these asset classes further adds diversification to your portfolio and therefore enhances the risk/return profile.

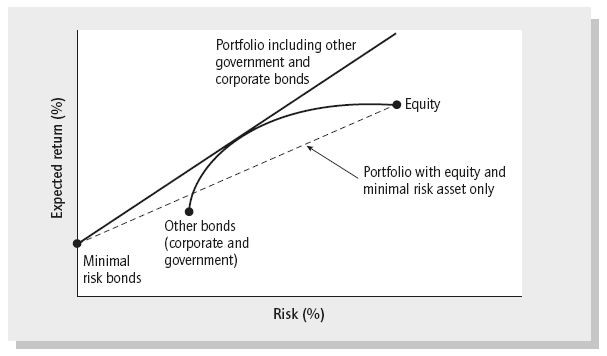

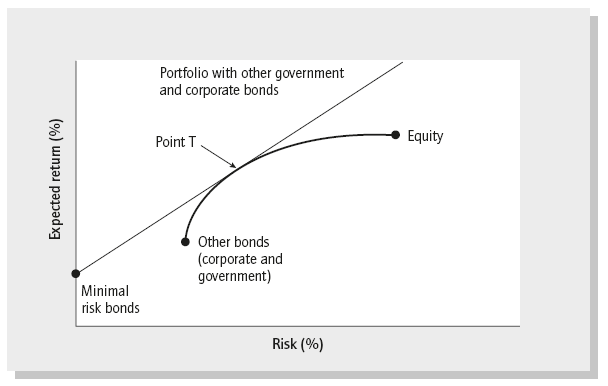

Figure 7.1 shows a portfolio including government and corporate bonds, instead of just the minimal risk asset and equities, which gives us higher expected returns. We can expect a better risk/return profile by adding these other government and corporate bonds to the minimal risk asset and world equity portfolio because the correlation between these additional bonds and the equity portfolio is not perfect (they don’t move in step and there are therefore diversification benefits from having some of both).

If the correlation between other government and corporate bonds and equities is 1 (i.e. they are perfectly correlated) there would be a straight line between the other bonds and equity points in Figure 7.1. Instead, by combining the other bonds with equities your portfolio will take on the risk/return profile like that of the curved line in Figure 7.1 (100% equities is the ‘Equity’ point and 100% other bonds is the ‘Other bonds’ point).1 We are essentially benefiting from the diversification benefits that the other government and corporate bonds add to the portfolio.

So what is the difference between the minimal risk bonds and the other government bonds we are now looking to add? Think of your minimal risk bonds as the core of your portfolio. This is not where you are looking to make money, but where you are looking to take a minimal risk. I am then adding all other government bonds, other than the minimal risk bonds that are already in your portfolio. So if your minimal risk bonds are UK government bonds, then the other government bonds you should consider adding are all but UK government bonds. It only makes sense to add government bonds that add expected returns to the portfolio (see later). If you added German government bonds to the UK ones you had as the minimal risk asset then the low yield of the German bonds would not add returns to your portfolio. And since you had the capital-preserving minimal risk asset already in the form of UK government bonds the German ones would not add much to your portfolio (unless you wanted a couple of different bonds as the minimal risk asset and included the German bonds for this purpose).

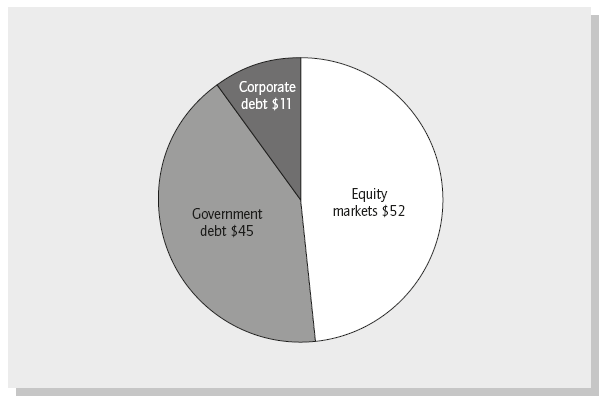

It may come as a surprise to some that the bond markets in the world actually exceed the equity markets by a healthy margin of about $30–40 trillion, or more than double the US annual GDP (US government debt/GDP is approximately 100% at present).2

Adding government bonds

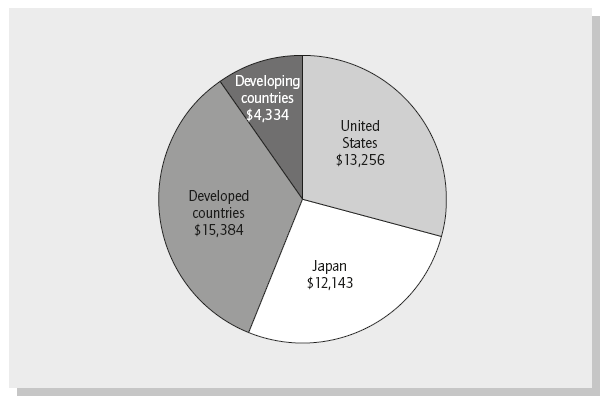

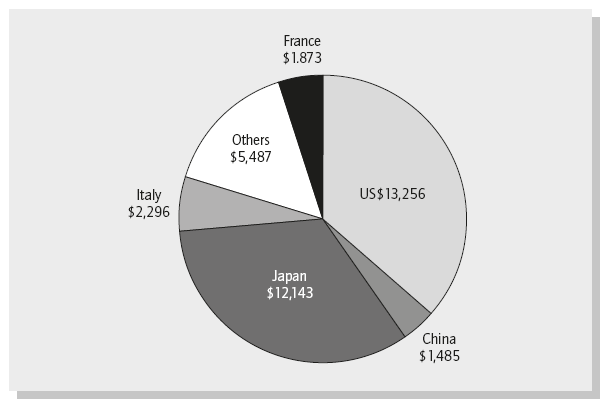

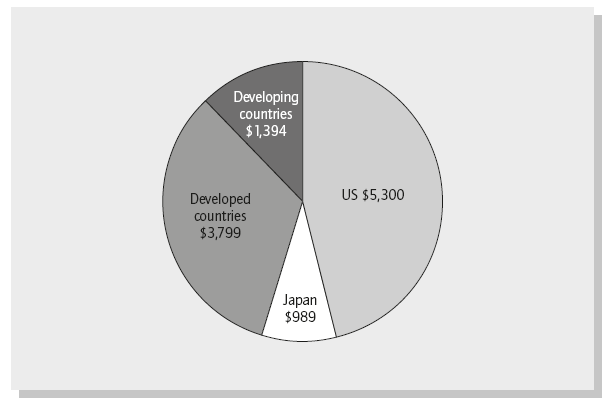

There are good reasons to add government bonds to your rational portfolio in addition to those you already hold as your minimal risk asset. Despite the world’s increasing international interdependence government bond portfolios are geographically diversified. Figure 7.2 shows government debt by geographical sector.

It is probably not surprising to many that the US debt is right at the top, considering the size of its economy, but that Japan is there alongside it may surprise some. With its very large debt/GDP ratio of over 200% Japan has managed to remain very indebted, but without incurring high, real interest rates as a result.3

As with equities, when adding other government bonds we would normally try to invest as broadly and cheaply as possible, and allocate in accordance to the relative values that the market has already ascribed to the various securities. However, you should amend this and not buy other government bonds in the proportions of the bonds outstanding that are shown in Figure 7.2.4

Earlier, we discussed how a highly rated government bond in the right currency provided the best investment for risk-averse investors, albeit at very low interest rates (at the time of writing). As an example, if I’m a UK-based investor looking for the lowest-risk investment for the next five years in sterling, I should buy five-year UK government bonds, perhaps in the form of inflation-protected bonds.

Based on data from Bank for International Settlements, end quarter 2 2012, www.bis.org

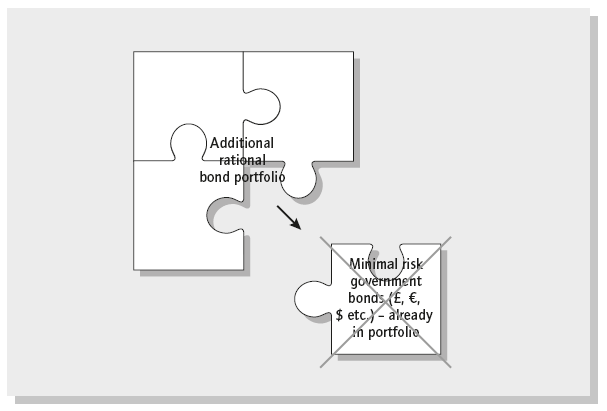

As we are now considering adding other government and corporate bonds to the rational portfolio of minimal risk bonds and equities, we should not just blindly add all the world’s government bonds (see Figure 7.3). We already have exposure to UK government bonds and therefore do not need to include more of these in the portfolio,5 we would just be doubling up on an exposure already taken to be the minimal risk investment.

How much the exclusion of the minimal risk asset from the world government bond portfolio changes the profile of the remaining portfolio depends on your base currency. If your base currency is $ or yen, then you would have reduced the universe of government bonds by a quarter. On the other hand, if your base currency is my native Danish kroner (with AAA-rated government bonds), then the impact on the world government bond portfolio would be negligible.

Only add government bonds if they increase expected returns

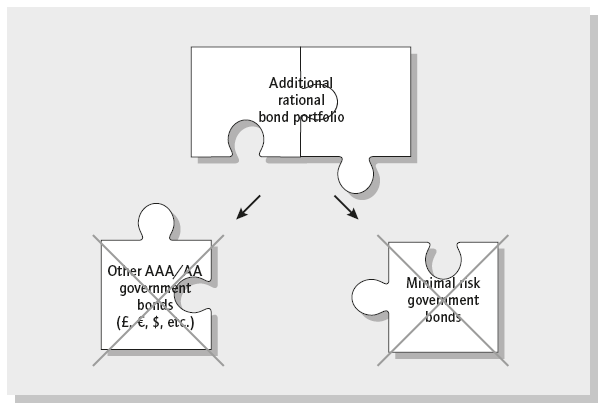

We discussed earlier how when adjusting for inflation investors in several highly rated government bonds should actually expect to earn a negative return, at least for short-term bonds. At the time of writing, the major countries with AAA or AA rating that offer a safe haven in their domestic currency but with little or no real return include Australia, Switzerland, Japan, Germany, the UK and the US, among others.

Consider the example of a sterling-based investor with UK government bonds as her minimal risk portfolio, contemplating adding other government bonds to her rational portfolio. From the UK bonds she gets almost no real returns, but also takes almost no risk. If she were to add bonds from the AAA- or AA-listed countries above she would also get no return, but would be taking currency risk. So she would get no greater returns from the foreign bonds, but take more risk.6

The rational investor thus has little to gain from adding AAA or AA government bonds to her portfolio other than as a minimal risk asset. If she was after a lower-risk portfolio she could add more of the minimal risk bonds (UK government bonds in this example). If she was willing to accept more risk in the portfolio she could get additional expected returns by either adding equities or government bonds that had a higher real return expectation than that offered by her minimal risk asset.

One caveat to excluding the other AAA/AA government bonds from the rational portfolio (see Figure 7.4): if you think there is credit risk in your minimal risk asset, then it may make sense to spread your investments among other AAA/AA credits. For example, if you are a UK investor and don’t consider the UK government’s credit entirely safe, then you could split your minimal risk investment into a couple of different AAA/AA bonds to diversify the credit. By diversifying you decrease the concentration risk of having your minimal risk asset from just one issuer (the UK government in this case), although it means taking currency risk with the other government bond holdings.7

The above is a departure from portfolio theory. According to portfolio theory you should add all the world’s investable assets in proportion to their values, and combine those investments with the risk-free asset to get to your desired risk level. Here I’m suggesting that you should only add assets that have a positive real expected return higher than your minimal risk government bonds, as you are otherwise adding currency risk without adding real expected returns.

The government bonds we should add to the rational portfolio

If the above seems like excluding a lot of government bonds, remember that you have only removed those already in the portfolio (the minimal risk asset) and other government bonds without meaningful additional expected real return (but with currency risk).

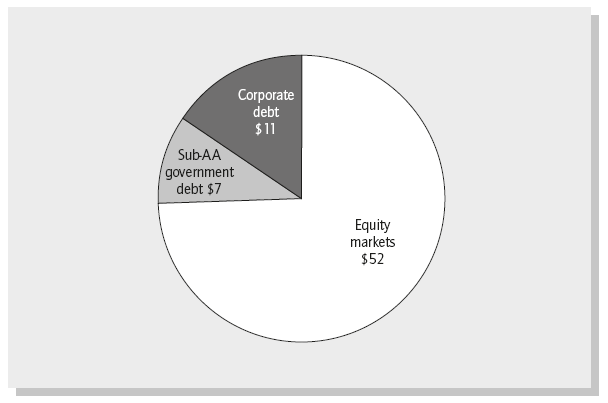

After omitting the minimal risk asset and other AAA/AA government bonds because of their low yield, the bonds you should consider adding to your portfolio are real return-generating government bonds (the rest) and corporate bonds (see Figure 7.5). And here we are still talking many trillions of dollars of potential investments.

Which government bonds you are left to invest in depends on how highly rated are the bonds that you want to eliminate. If you were only to eliminate bonds that were AAA rated and wanted to invest in the remaining then those would be distributed as shown in Figure 7.6.

What you will notice is that this list is dominated by the US and Japan, ‘only’ AA rated by S&P at the time of writing, and thus not deemed entirely without risk. But if you, like most investors, take the view that these AA-rated bonds still did not offer enough expected real return to be worth adding to the portfolio (besides being the minimal risk for investors in those currencies), and that you only wanted to add government bonds rated below AA (to get additional yield), then the remaining world government bonds would be distributed as shown in Figure 7.7.

Based on data from Bank for International Settlements, end quarter 2 2012, www.bis.org

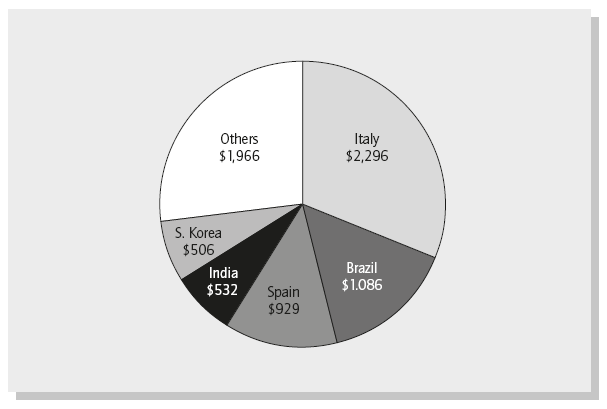

The way to read Figure 7.7 would be as follows:

I am an investor who, in addition to my minimal risk asset and equity portfolio, wants to add a diversified group of other government bonds. Since I already have exposure to my minimal risk government bonds and don’t think government bonds from countries rated AAA/AA offer enough yield to be interesting, which government bonds should I be adding?

While in principle you should buy the bonds rated below AA according to their market values, in reality it is not practical for some investors to find investment products that represent so many different countries. Instead you might buy an emerging market government bond exchange traded fund (ETF) and combine that with a product covering sub-AA eurozone government bonds. The combination you end up with would not be exactly in the proportions of the sub-AA-rated bonds in Figure 7.7, but get you a long way towards adding a diversified group of real return generating government bonds to your rational portfolio.

Bond yields move a lot. Even at the height of the 2008 financial crisis the yield on 10-year Greek government debt was 5–6% compared to the current unsustainable levels. This was considered a safe investment although events since suggest that it wasn’t and provide a good example of how the credit quality of an individual government can decline at an alarming pace if the markets lose confidence in repayment. Despite the fact that the government bonds in the sub-AA chart (see Figure 7.7) are geographically diversified investments, you should expect some correlation between them. Not only do some of the European countries operate in the same currency and open market (the EU), but all countries are subject to changes in the world economy, besides their unique domestic changes, and are similarly vulnerable to changes in market sentiment.

Figure 7.7 Below AA government debt in $ billions

Based on data from Bank for International Settlements, end quarter 2 2012, www.bis.org

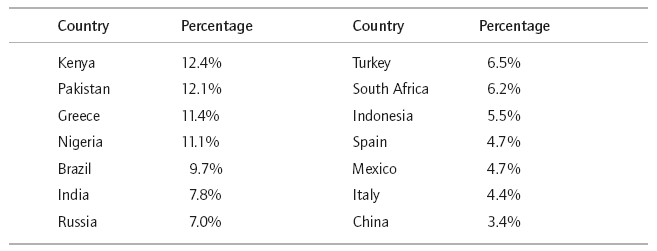

Table 7.1 shows the yields on various selected 10-year government bonds that fit into the real return-generating government category at the time of writing. While the table below is for 10-year bonds only (you should try to get a mix of maturities) it gives you an idea of the interest you can expect from these lower-rated bonds.

Based on data from www.tradingeconomics.com

These yields are in local currency-denominated bonds. Since the expected inflation on the Brazilian real is greater than that of the euro the inflation-adjusted return is not as high as suggested above. In other words, Brazil is not as poor a credit risk as suggested by the table.

In addition, it is unfair to say, for example, that you would expect to make a nominal 11.4% return from Greek bonds. The high return implies an increased probability that Greece will default or that you will somehow not be paid in full.

There are some further points when considering adding other government bonds to the portfolio:

- As you add additional government bonds from these lower-rated countries do so in a range of maturities. On top of diversifying geographically this will avoid concentration of the interest rate risk. Practically, adding these bonds is best done via buying a range of ETFs or low-cost investment funds that buy the underlying bonds for a low fee. For example, you could buy an emerging markets bond ETF that will give you an underlying exposure to the wide range of lower-rated government bonds in different maturities that you are looking for. Likewise, with some of the sub-AA-rated developed country government bonds. By holding the bonds via ETFs or investment funds you don’t have to worry about buying new bonds as old ones mature. The provider will do this for you and ensure that your maturity profile remains fairly stable, which is what you want.

- Be careful that you don’t add concentration risk when you are meant to be diversifying. In Table 7.1 (that excludes the AAA bonds only) if your minimal risk asset had been US bonds and thus excluded, Japanese bonds would have been over 50% of the remaining amount. These charts and tables should serve to remind you to broadly diversify your government bond holdings to those that add real returns – not increase concentration risk to one issuer (e.g. Japan).

- Buying the government bonds listed above in proportion to their shares of all sub-AA-rated government bonds would be an expensive administrative headache, and there are no access products like ETFs or index funds that do exactly that for you. But if you don’t get the proportions exactly right that is fine too. Perhaps buy some low-cost emerging market government bond funds and add to those some exposure to below-AA developed market government bond funds. If you do this roughly in proportion so that each country’s or region’s share is roughly similar to that of its share in Table 7.1 then that is a good approximation.

- Keep an eye out for changes in the make-up of real return-generating government bonds. Some of the bonds rated lower than AA may have increased in credit quality to the point where they don’t really add real returns in excess of your minimal risk asset, or perhaps more likely some of the governments rated AA or above may have declined in credit quality to the point where they are worth adding as a real return generator. I look forward to re-reading this book in 10 years’ time and with the benefit of hindsight seeing which governments moved up or down in credit quality. Look to make these changes as you rebalance your portfolio occasionally. Since your real-return generating government bond portfolio is well diversified, changes to it will hopefully not be too dramatic, but likewise keep in mind that unlike the minimal risk asset, world equities and corporate bonds, this is the one segment of the rational portfolio where a broad-index-type access product like an ETF or index tracker will be unlikely to suit your needs. You probably have to put a few products together yourself to create a portfolio of sub-AA-rated government bonds, the make-up of which will change over time.

Adding corporate bonds

In addition to adding sub-AA government bonds you should consider adding a board portfolio of corporate bonds to your portfolio (see Figure 7.8).

Traditionally, whenever investment books like this one have proposed investment in corporate bonds (as most do) they were referring to US-based bonds. This was because their audience was often made up of US or dollar-based investors, and besides, foreign bonds were expensive and impractical to buy. While the ease of investing in non-US bonds is rapidly improving, the US dominance is still prevalent, at least relative to the US share of world GDP, at around 20%. We saw earlier that the world equity portfolio’s largest constituent by a wide margin is also the US, and if you only add US corporate bonds you will not get the diversification benefits of international exposure. But this is not just true of US investors. Any investor that adds corporate bonds only in their home geography may have diversified asset classes, but at the same time have increased geographic concentration. Adding a broad portfolio of international corporate bonds can rectify this concentration issue.

Based on data from Bank for International Settlements, end 2011, www.bis.org

Looking to the future, the non-US portion of world corporate debt is likely to increase further and thus augment the importance of getting both the asset class diversification of adding bonds and also the geographic diversification of adding international ones to your rational portfolio.8

When you add corporate bonds to your rational portfolio, consider Figure 7.9 and make sure you diversify internationally. At this time, around 55% of the world’s corporate bonds are non-US, and like the US ones represent thousands of individual bonds of different maturities, industries, geographic areas and credit qualities. Ignoring the great diversification benefits from adding index-tracking ETFs or funds made up of these many thousand foreign bonds to your rational portfolio would be an omission.

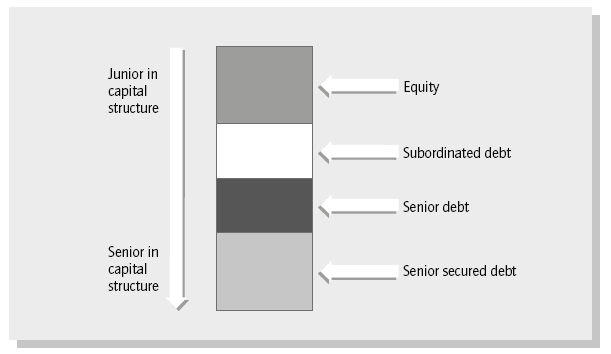

It makes sense that while there are very high-yielding bonds, in general return expectations from bonds are lower than equities. As a bond holder you are a lender – to either a corporation or government – whereas as an equity holder you are an owner. The seniority of the capital structure reflects this. In receiving the distribution of the cash flows of a company the debt holders are entitled to their interest payments before dividends are paid to equity holders. Likewise, in default, debt holders have the first claim on the assets of a company. A lower expected return is the price of this superior place in the capital structure (see Figure 7.10).

Just as all the various layers of seniority in the capital structure are represented in the world corporate bond portfolio, the bonds vary significantly in maturity. And as with the case of government bonds the longer-maturity corporate bonds of similar credit quality typically yield more than their shorter-term peers.9

If history is any guide …

Compared to equity returns, figuring out historical returns for broad bond indices is not straightforward. Until fairly recently there was a dearth of investable index products available to investors who wanted bond exposure, other than perhaps that of the major country government bonds or US corporate bonds. Things are slowly getting better and the next decade will see further expansion in the amount of fixed-income products available for the retail investor.

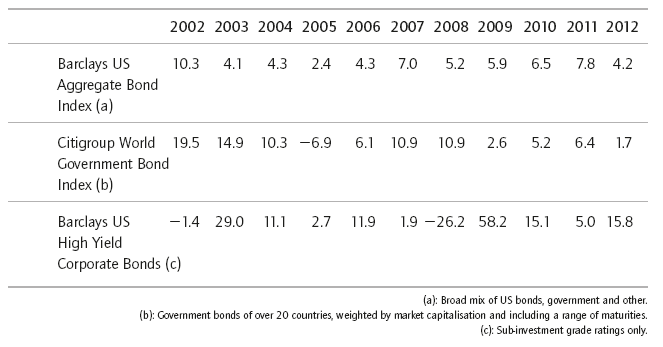

The historical indices that do go back some time have a heavy US bias and until recently broad-based indices were hard to come by, much less ones you could actually create as a product. Table 7.2 shows the performance data for some broad bond indices.

Although the time period shown in Table 7.2 is far too short to make meaningful conclusions, 2008 stands out as an interesting data point. Both the US aggregate and global government bond indices had positive returns in a terrible equity market.

The outperformance of highly rated bonds in a tough market environment points to the potential advantage of adding fixed income to the rational portfolio. As equity markets collapsed, investors sought security in highly rated bonds. There was a belief that whatever happened, the bonds would be repaid at maturity, while nobody knew what would happen to equities.

The large decline in the Barclays US High Yield index in 2008 was no surprise. Companies with high-yield bonds outstanding were dependent on a benign economic environment to repay their debts. With a collapsing market and grim forecasts as a result of the crash, those future repayments were put in doubt and investors sold high-yield bonds as a result.

Generally, I would caution investors about reading too much from this short data period. There is no saying that future crises or correlations will be like those of the past. In fact, as a writer based in Europe I find it entirely conceivable that a future crisis could easily involve government credit issues with their bonds declining in value instead of being a safe asset. If so, you could easily see both equities and government and corporate bonds collapsing at the same time.

So while there is no certainty as to what might happen in a future crisis, adding other government and corporate bonds to the portfolio makes good sense. We are adding bonds from a very broad range of countries, maturities, currencies and risk levels, and with both government and corporate issuers. This kind of asset class diversification to the world equity portfolio as a return generator is likely to serve the portfolio well, with lower-risk and more-diversified returns.

Getting practical

As we look to add bonds to the portfolio, here are a few pointers:

- Buy a broad-based bond exposure, both in terms of geography and type of bond.

- Buy index-tracking products where available. You generally don’t want to pay the higher fees of active management, but in the case of adding bonds cheaply actively managed funds may be a good choice when index trackers are unavailable.

- Look for new product development. Particularly in the bond space this will be important. My prediction is that the broadly available bond offering will be much expanded in the years ahead and you will probably be able to benefit from this.

Later, when discussing implementation (see Chapter 14) I’ll describe a couple of good alternatives to gain broad and cheap bond exposure as part of your rational portfolio.

Typical criticisms of adding bonds to a portfolio

Compared to equities there are fewer good bond indices and they are not as well known

True. Many investors don’t even know they exist. But what we care about is the availability of products that represent a broad range of bonds, both geographically and by type. Although this sector is still not up to the level of equities it is improving.

You will tend to overweight the debt of indebted countries and companies (they have more debt outstanding as a fraction of company value or GDP)

True. But the prices should reflect the higher indebtedness. In the future there could be government bond indices driven by the GDP of a country, but those that exist are still not that widespread.

In certain countries the trading of bonds is very expensive, rendering them a bad risk/return prospect

The key thing to figure out is if you are at a cost disadvantage compared to other market participants. If you are, it may make sense to stay away. If costs are just high for everyone, the higher costs should be reflected in the price and not affect the bond’s risk/return profile.

The income from bond coupon payments renders them tax inefficient

Important point. If you are unable to find tax-efficient products (ETFs, etc.) you may consider tax-advantageous bonds in your geographic area, such as municipal bonds in the US. A tax disadvantage can easily eliminate any investment advantage.

Bond products only represent a portion of the total bonds outstanding

It would be impractical and/or impossible to buy a small portion of all outstanding bonds in the world. Indices try to ensure that they can be practically implemented and thus avoid small and illiquid bonds; as with equity markets (to a lesser degree) this is a simplification we have to live with.

Bonds are mainly dollar denominated. This is an issue for non-US investors

Yes, a large portion is in dollars. This is because of the US’s dominance of government and corporate bonds, but also because many that issue bonds in currencies other than their home currency do so in dollars. You can partly alleviate this problem if your minimal risk asset is not US government bonds and thus exclude them from your other government bond allocation. Also, don’t ignore the large and increasing number of international corporate bonds.

It is expensive to trade bonds

Unless you are a big institution you should buy products like ETFs, bond index funds or even cheap managed bond funds that acquire the bonds for you. With the exception of buying government bonds directly from the treasury, you can typically only buy bonds in larger ticket sizes and by buying aggregating products like ETFs or index funds scale and cost advantages are gained that are hard for the individual investor to match. (This is also discussed later in Chapter 14.)

Corporate bond returns also depend on credit quality

Earlier we discussed how the equity risk premium to the minimal risk bonds is about 4–5% a year. What about risky governments and corporate bonds?

Corporate bonds rank above equities in the capital structure of firms and therefore have superior rights to cash flows or capital. It therefore seems reasonable that corporate bonds should have a lower return expectation than equities. How much lower obviously depends on the mix of corporate bonds in the index. At the time of writing, the yield to redemption for the Finra/Bloomberg US investment grade and high-yield indices were as follows (www.bloomberg.com/markets/rates-bonds/corporate-bonds):

| Current yield | |

| US investment grade | 3.13% |

| US high yield | 5.65% |

For government bonds, we saw earlier what the yield on a 10-year bond was for various ‘risky’ countries. But as was the case with those government bonds we can’t simply deduce from the data above that high-yield bonds always will do better than investment grade ones. The high-yield bonds are likely to have a much higher default rate (just like higher-yielding government bonds will default more often), and the return net of those defaults will be lower than in the unlikely case where all the high-yielding bonds are repaid in full.

Return expectations of the rational portfolio

Below are some estimates for returns of the various asset classes we have discussed so far in this book. Based on a mix of academic research, historical returns, a study of the financial markets and my own judgement I have outlined what I would consider reasonable expected returns for each asset class, above the rate of inflation as follows:

| Annual real return expectations | ||

| Minimal risk asset | 0.50% | (UK, US, German government debt or similar) |

| ‘Risky’ government bonds | 2.00% | (sub-AA-rated countries) |

| Corporate bonds | 3.00% | (mix of maturities, countries and credit quality) |

| World equities | 5.00% | (4.5% equity risk premium) |

In later sections, we look at individual attitudes towards risk. The minimal risk asset is obviously deemed to have little risk (thus the name), and we have discussed previously how a reasonable estimate of risk for equity markets is a 20% annual standard deviation. While we can reasonably estimate the risk of the government and corporate portfolio relative to the minimal risk asset and equities (with government bonds closer to minimal risk, and corporate bonds closer to equities), how the various allocations act relative to each other is harder to predict.

Although you have added diversification to your portfolio by adding risky government and corporate bonds, adding bonds is not always guaranteed beneficial. The correlation between those assets and the rest of your portfolio is likely to be higher during duress than in a steady state, even as some higher-rated bonds may increase in value as a safe haven during a storm.

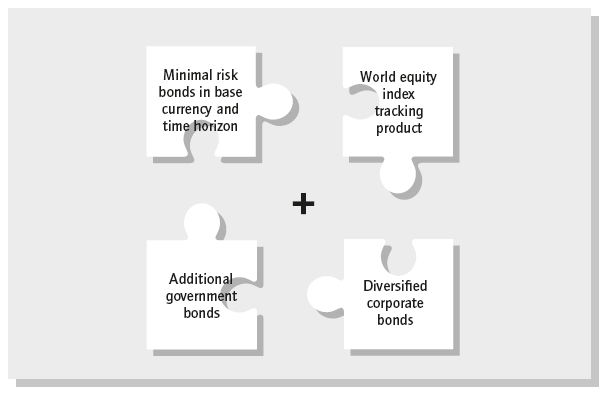

Adjusting the rational portfolio

Before we introduced risky bonds into the portfolio things were easy. If you wanted no risk, you could pick the minimal risk asset; if you wanted a lot of risk, you could pick a broad-based equity portfolio. If you wanted a risk profile in between the two, you allocated between the two. And do this in a cheap and tax-efficient way. Simple.

Adding other bonds to the portfolio gives additional diversification benefits to the portfolio, but does so at the expense of more complexity. When deciding on what portion of your portfolio you should allocate to bonds, start by going back to your premise as a rational investor. We assumed each dollar invested in the world markets is equally well informed, and as a result we should try to replicate the exposures of all markets.

The split of the approximately $100 trillion market that is world equities, and world government and corporate bonds, is roughly as shown in Figure 7.11. But after adjusting the portfolio to exclude the minimal risk bonds and other highly rated and low-yielding bonds, the split is quite different. Figure 7.12 is the same pie chart but excluding AAA/AA-rated government bonds.

Using this mix of assets as a rough guide to our portfolio allocation we could allocate our risky investments as follows:

| World equity markets | 75% |

| Sub-AA government debt | 10% |

| Corporate debt | 15% |

If you combine your investment in the minimal risk asset with investments in equities, risky government bonds and corporate bonds in those proportions you are doing well. You will have allocated your investments roughly in the same proportions as the aggregate market participants who have been choosing between a wide array of investable assets in search of the best risk/return. If you now do so in a cost- and tax-efficient manner, while thinking about your risk levels, you will have created a very strong portfolio. Graphically this updated portfolio is illustrated as point T in Figure 7.13.

If your risk preference is lower than point T, you combine the ‘T’ portfolio (as in Figure 7.13) with the minimal risk asset to get the desired portfolio risk.

Using equity risk insights in the context of a full rational portfolio

My reason for focusing on equities is that we have good data to gain some meaningful insights about the risk of investing in equity markets, whereas it’s harder to be exact about the overall portfolio risk. This is because while we can try to quantify the risk of government and corporate bonds, it is harder to predict how those move relative to each other and to equities (correlation) with any accuracy, and therefore what the aggregate portfolio risk is.

Extrapolating an understanding of equity market risk to the overall portfolio you need to bear the following in mind:

- Try to understand the risks you are taking with an investment in the world equity markets.

- Realise that your minimal risk asset is not entirely without risk, but has a far lower risk than the equity markets. Longer-maturity bonds will fluctuate more in value than shorter-term ones.

- Other government and corporate bonds will typically have a risk level between equities and the minimal risk bonds. The riskier the bonds, the more they will be like equities and perhaps move in price more like equities if markets drop, but it is hard to be exact about that. As a very rough rule of thumb, assume that the other government and corporate bonds have slightly less than half the risk of equities, but will move more like equities in terrible markets than when markets are stable.

The rational portfolio allocations

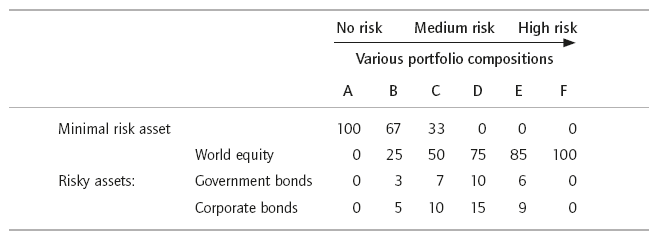

So, now we have a rational portfolio as shown in Figure 7.14. Incorporating the points above about the relative proportions of risky government and corporate bonds relative to equities, the rational portfolio could look like that in Table 7.3.

The allocations shown in the table are the best because they are based on the proportions of values that the market already ascribes to them, with the caveat that I have excluded non-return generating, highly rated government bonds. So apart from those highly rated bonds, the ratio of equities, government and corporate bonds is in line with the market value proportions in the world today. And if we allocate along the same lines as the efficient markets we will achieve maximum diversification and the best risk/return profile.

We need to take a combination of equities and other government and corporate bonds and combine that with our ‘safety asset’, the minimal risk asset. How much risk we want is then determined by how much of the minimal risk asset, and how much of the combination of the other asset classes, we want. Construct your portfolio in this way and you will have an outstanding portfolio for the long run.

In implementing the portfolios outlined above look for products that, as closely as possible, represent the various asset classes:

If the strategy for investing above seems simple, it is because it is. As a rational investor who is willing to add a bit of complexity to the all minimal risk/equity mix from earlier, we are simply adding real return-generating bonds in the proportions that they exist in the world. We think that the normal functioning of the market has caused the prices of the many debt and equity securities to be such that they reflect the risk/return characteristic of that security.

Of course not every investment in the world is perfectly efficiently priced. If this was the case, and everybody believed it, then there would be no trading. Everyone would accept that the prices reflected all information and the security’s risk/return contribution. But that is not the point. The point is that we do not think that we are in a position to know better than the prices set by the market and as a result should not try to reallocate our portfolio to get better returns.

Special case: if you want a lot of risk

Theory and practice collide in the case where an investor’s risk preference is higher than point T in Figure 7.13. Theory suggests that the investor should borrow money and use that borrowed money to buy more of the ‘T’ portfolio.10 In reality many investors either don’t ever want to borrow to invest or simply can’t find the money to do so. Particularly post-2008, when geared investors got burned badly as loans got called at the worst possible time, investing with borrowed money is often not a real or desired alternative.

For investors with a higher risk preference than point T, I would suggest buying more of the world equity portfolio and fewer bonds (instead of borrowing money to buy more of the mix of equities and bonds) – see Figure 7.15.

If you want even more risk than being 100% invested in world equities there are leveraged ETFs. Simplistically, the way they work is that the provider takes your £50 and uses that as collateral to borrow another £50, and then invests the £100 (in the case of a 50% leverage product). You will then have the exposure to the market of £100 despite only having invested £50. This obviously works well if markets are going up, but will quickly hurt badly in declining markets.

1 As discussed elsewhere these graphs are mainly for illustration, particularly as the risk and correlations change continuously.

2 Note that a lot of debt (about $28 billion) is issued outside the country of the issuer. This may be a French company issuing debt in the US in dollars. This is important in that you may buy a bond in the US, but have the underlying exposure as that of a French company.

3 At the time of writing, shorting Japanese government debt is a popular hedge fund trade as the managers deem the debt levels unsustainable, but according to a Japanese hedge fund manager friend of mine the arguments used are hardly new and in his view this is not a ‘slam dunk’ trade. Time will tell.

4 As a first gut feel of why this ‘buy the world’ strategy may not work for everyone, consider that over half your government bond portfolio would be Japanese and US government bonds. This not only adds quite a bit of concentration risk to two issuers, but also adds currency risk and minimal real expected returns due to the low/negative real yields on those bonds.

5 One minor caveat to this argument; if the mix of maturities you added to get to your minimal risk asset is very different from the overall mix of maturities issued by that government then it makes sense to amend the minimal risk allocations. So if you only had very short-term bonds in your minimal risk allocation, yet are willing to add more risk in the form of equities and other bonds, it makes sense for this allocation to include some longer-term bond exposure from that same government.

6 There is of course the possibility that the other currencies appreciate against sterling. So if you held US bonds and the dollar went up in value relative to the pound, those bonds would be worth more in sterling terms. That being the case, although this risk can also lead to you making money it is not a risk you get compensated for taking in the form of higher expected returns.

7 By adding other safe bonds to your minimal risk bonds you are also diversifying your interest rate risk away from that of just one currency (you have exposure to a couple of different yield curves), but for the purposes of keeping the portfolio simple I don’t think this diversification is worth the added complexity and currency risk of those bonds.

8 We have left out the large and broad market of financial institution debt. This includes interbank debt, but also various obligations issued by financial institutions. This is less of a transparent market for the rational investor and someone with the broad exposures discussed in this book already have a lot of the same exposures via the existing bond and equity positions in their portfolio.

9 Occasionally the yield curve is inverted (long-term yields are lower than short-term ones). This is when the market is expecting the interest rate to drop in the future.

10 The straight line between minimal risk, point T, and up to the right assumes that the investor can borrow at the same rate as the minimal risk bond. In reality the borrowing rate for the investor would be higher and the curve to the right of point T would be flatter to reflect the lower expected return (higher borrowing costs) as risk increases.