What is omitted from your rational portfolio and why

Avoid investments that require an edge or those you already have exposure to

It wouldn’t surprise me if the portfolio I have suggested has many sceptics. It probably looks too simple to make much sense, and leaves out several successful asset classes that have dominated not only the financial press, but also our popular culture. I live in London, a city which has seen an incredible rise in property prices over the past decades. Because of this most investors take for granted that any reasonable portfolio consists at least partly of domestic property. London is one of the places in the world that came through the crash relatively unscathed so the fans of property maintain their continuing belief.

In this chapter, I discuss other popular asset classes and their absence from the simple rational portfolio. We will see that appreciating that we are without an edge is even more important as we move away from the public equity and bond markets and into sectors that are typically closer to the local economies that we individually know and feel a part of. It may seem strange to have a whole chapter on things to leave out of your portfolio, but it is important to remember why: the portfolio in this book is for people who have no edge to outperform, and should be a simple and cheap portfolio as a result. The rational portfolio is certainly simple and cheap, and requires no edge in the three asset classes it suggests: the minimal risk asset, world equities and other government and corporate bonds. The asset classes discussed in this chapter will undoubtedly make many investors phenomenally rich in the future, but those will either be investors who have a great edge, charge others a lot of fees or are lucky. Since you don’t want to count on luck, can’t charge other people large fees and have no edge – and probably have a lot of exposures anyway – you should stay away. The eliminated asset classes are still important because you need to be sure that you know they have been considered and that there are good reasons for leaving them out.

A few recurring issues with these other asset classes make them unsuitable for the rational portfolio:

- You don’t have an edge or special insight/knowledge to pick the outperforming sub-set of the asset class.

- The whole asset class does not necessarily have return expectations in excess of the minimal risk asset in future.

- You already have exposure to the asset class via companies represented both in your broad equity and potentially corporate bond exposures. Do you really need to increase them further?

- The other asset classes can be very illiquid – do you get compensated with higher returns for this disadvantage?

- Other asset class exposures can be very expensive in fees and expenses. Unless you have a great edge in picking the right products this can destroy any return advantage.

- There is a good case for adding quoted property investments to the rational portfolio although only in limited size relative to the overall equity investment. But because it is small and you may already have this exposure indirectly elsewhere in your rational portfolio, and for the sake of simplicity, property investments have been excluded from the simple rational portfolio.

So, the excluded asset classes discussed in this chapter are:

- property

- direct investments, private property funds

- residential property

- quoted property holdings

- private equity, venture capital and hedge funds

- commodities

- private investments

- collectibles.

Mortgage-backed, mortgage-related and asset-backed securities, other types of quasi-government debt and other debt instruments issued by financial institutions are also excluded. This is because some of them fall into the property category, and others are alternatives to the minimal risk investment, particularly in cases where the investments are quasi government and there are tax advantages. Also, a lot of the exposures those kinds of debts give you are captured indirectly elsewhere in the portfolio, but they are without easy products to gain access to – so in the interest of simplicity and ease of implementation these additional investment possibilities do not add enough additional value to be included. Financial institutions’ debt is a gigantic market (bigger than the corporate debt market), but less of a relevant product for the rational investor as a lot of it relates to the wholesale funding market for financial institutions and there are no easily accessible products available to most retail investors.

Property – don’t do it unless you have an edge

Rational investors would not expect to do any better than the general property market, less any cost disadvantage they may have, so the best expected return from property would be that of the whole sector in the relevant area. Someone investing in private/direct property projects or private funds that invest in property often invests in the same geographical area as their other assets and as we have seen this exposes them to a great concentration of risk in their overall portfolio as a result. There is a good chance that whatever may cause the local/regional property market to decline could affect other local assets, in addition to the value of investors’ private homes. Unless you get compensated for this concentration risk by getting higher expected investment returns, the concentration is a risk worth avoiding and as you are without an edge you would not predict this outperformance.

Likewise, consider the illiquid nature of private property investments. While even very large investors can liquidate world equity market investments in a short period of time, trying to sell a direct property investment or a stake in a private investment when you need the money is rarely a recipe for success. And while there have clearly been successful property booms, if you are selling at a tough time for property assets generally then others probably need to sell property at the same time. With liquidity drying up for those investors who are forced to sell their investments, this situation is terrible.

One of the reasons so many investors are fascinated by property investments has to do with physical proximity. People who are interested in investing often can’t help themselves spotting a great investment opportunity and where better to see it than right in front of you. You might see a decrepit building in a great location and wonder why nobody is fixing it up, and think that you might just be the best-positioned investor to do it. Or hear through a friend that planning permission is going through for an upscale development that would lift the value of an adjacent building, and so forth. Like a lot of people in London, I have been guilty of feeling like a property expert and thought I was an astute property investor until I realised that I had just been lucky and bought into a rising market.

I don’t doubt that many property investors are people with local connections or insight to do this well. Perhaps they have an edge, but unless you are one of those plugged in people, you probably do not have an edge in the property markets. And like the argument of picking active equity managers, picking property investment funds suggests an indirect edge if you claim to be able to pick a manager who has an edge.

So how do you know if you are one of these investors with an edge in property markets? As in the public equity markets it is not always easy to know if you have an edge. Those who perform poorly have a great excuse and those that perform well in the property market are unlikely to think it is luck and will always have other great reasons: they saw something others didn’t, knew something, understood something and heard something. Something. Just be honest with yourself as you consider your edge. It can be expensive to think you have it if you don’t.

Has residential property really been that great?

The best estimate of residential property performance is the Case-Shiller House Price index which represents the price changes in US residential homes. Professor Robert Shiller describes the housing index along with other interesting ideas in his excellent book Irrational Exuberance (Princeton University Press, 2005). To my knowledge there isn’t a property index that covers all forms of residential property investment across many countries that goes back many decades for us to analyse.

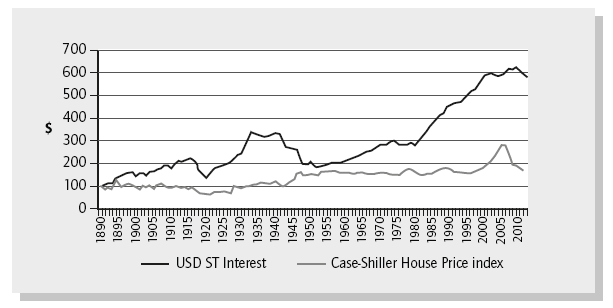

Using the Case-Shiller index as a proxy for residential property investments since 1890 we can compare the returns of the housing market to an investment over the same time period in short-term US government bonds (see Figure 9.1).

The first thing to note is that over the past century we would have done far better investing in US government bonds than in residential property. It is of course easy to criticise analysis like this for not correctly incorporating rental income (or the ownership benefit of not paying rent), maintenance and improvement costs, transaction costs, insurance costs, and transaction and on-going tax. Or not being international. I would agree that it is hard to claim that these things are an overly exact science, but this index questions the premise that property investments are necessarily a huge profit centre.

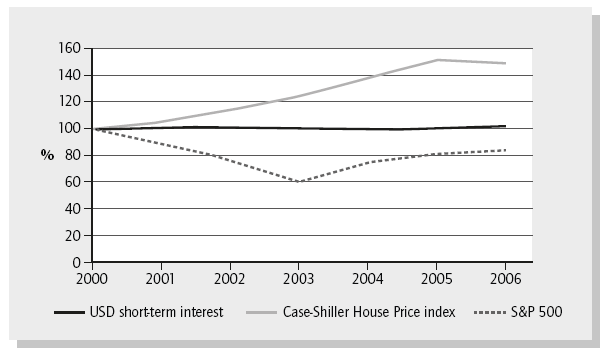

However, we can also see why property was such a hot investment in the years before the sub-prime crisis (see Figure 9.2).

Figure 9.2 Case-Shiller House Price index versus short-term US government debt and S&P 500, all inflation adjusted

As property markets outperformed debt and equity markets, many saw this as a sign of things to come and jumped on the bandwagon, even as longerterm data did not suggest that residential property markets outperform in the long run. Besides, it’s always easier to sell an investment in something that has recently done well, and property investments certainly did well until the bubble burst. Keep in mind that many countries have regulations or incentives that promote house purchase. As a good friend commented, ‘Where else can you get a subsidised 90% loan-to-value investment with no taxes?’ Of course, all those things should help house prices, but should already be reflected in the prices.

A home

A friend of mine and I were having a conversation a couple of years ago, soon after he had lost his job. He did not have much in the form of savings, about £20,000, but could probably support his family for a year without lowering their living standards. Almost as an aside, my friend said, ‘Thank God we have the house.’

Five years earlier he and his wife had put all their savings into the equity of their house, obtained a loan-to-value mortgage of 80% and bought the cottage of their dreams in South London for £200,000. They loved the house and financially it had been a huge success. An estate agent had told them that they would have no problems selling the house for £250,000 – a tax-free gain of £50,000.

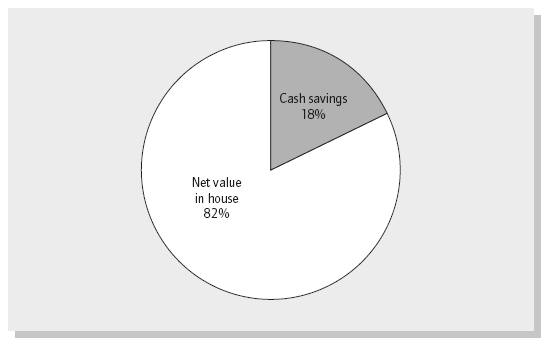

In my view, their situation is fairly typical of a London couple; the vast majority of their wealth is tied up in London property (see Figure 9.3).

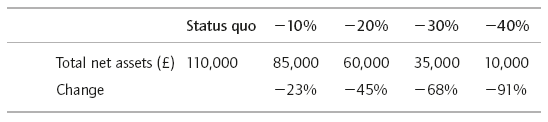

Not only were my friends dependent on London property, but with their mortgage they were heavily geared. A decline in the London housing market could have a very significant impact on their net assets, the success of the house purchase not withstanding. Table 9.1 shows how this couple’s net assets of £110,000 (house of £250,000 less £160,000 mortgage plus £20,000 other savings) would be affected by different movements in London property prices, assuming their house moved with the market.

In essence, my friends were taking an incredibly concentrated bet on the London property market. If the housing market in general, and their home specifically, sufferered a decline of 20% they would see their assets decline by 45%; a 40% decline in the value of the house and my friends would almost be bankrupt.

I thought I was stating the obvious, my friend saw no sense in my argument. He pointed out that if they had taken the £40,000 that they put down for the house and put it in the bank instead, their life savings would be £60,000 today instead of £110,000. Where was the sense in that? I mentioned that if you ignored that a lot of people thought there was a lot of additional quality of life from owning where you live instead of renting, they had essentially taken a geared bet on London property and been lucky. Again my friend thought I was wrong. He felt that they knew the local market and had been able to find an extra-attractive house and that when they bought the house the local property market was about to take off. Instead of luck, they had been astute house buyers. At this point I kept my mouth shut.

I understand and appreciate the desire to own your house instead of renting, and also understand that we badly want to believe that we have made an astute purchase with what for many people is the largest investment of their lives. But buying a property may mean compromising the portfolio of our total assets, by increasing concentration risk and correlation risk in a leveraged way, and I would strongly suggest that any house owner takes a look at the fraction of total assets that local property constitutes.1 Then question what would happen if your local property market dropped in value by various double-digit percentages. Would it matter? Is this likely to happen at the same time as you lose your job or other savings? Would you risk the scenario of being unable to make payments on a mortgage or forced to refinance the mortgage, thereby risking having to realise the price change and being unable to ride out the stormy market?

A major part of good portfolio management is about not putting all your eggs in one basket and subjecting yourself to the risk of bad things happening all at once in an unpredictable fashion. For many who were hurt in the recent property bubble, this was what happened. But I do understand why individual investors put great intangible value to owning their own house on top of the large monetary value many have realised over the past decades. My parents have lived in the same house for about 40 years. Their house is not an integral part of their portfolio or an investment – it is a home. If that is somehow sub-optimal from a portfolio management perspective, so be it.

The case for commercial property

Despite the questionable history of great returns in residential property and its presence in many portfolios through home ownership, general property investing has been a thriving investment for some over the years and an integral part of many diversified portfolios. While there is good evidence that the return profile for commercial property has been attractive in the past, to my knowledge there hasn’t been a global diversified investable property index like there is in the stock markets with the MSCI World index and others. As an example, the FTSE EPRA/NAREIT Global index was not launched until 2009 and even while there is global data going further back, it is less clear how a globally diversified property investment product would have fared.

Proponents of property investment suggest that it is a separate asset class with limited correlation with equity and other markets. (Although only tracking residential property, the correlation between the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the Case-Shiller index since 1900 is only 0.19.) Limited correlation with other asset classes is obviously a good thing and if this low correlation is replicated in future then commercial property investment could provide a good diversifier (although virtually all publicly traded property investments suffered in 2008 along with the rest of the market, suggesting low correlation is not universally the case). With low correlation you don’t need that high a return expectation for a property investment to make sense and investing in a diversified global portfolio of property investments would also add geographic diversification.

But despite the promisingly low correlation and apparent good historical performance of commercial property generally, the FTSE NAREIT index mentioned above represents quoted underlying property investment companies with a market capitalisation that represents only 2–3% of the global equity market’s total market capitalisation.2 At the time of writing the largest constituent in the index has a market value of around $25 billion and the entire index of around 400 constituents spread around the world has a value of about $650 billion, or not much above the market value of a couple of leading individual companies. So while the global index provides the kind of good and well-diversified property exposure an investor should want, if you allocate far more to property than the sub-5% of the world market values, you run the risk of over-allocating to property, particularly considering the other ways you already have direct and indirect exposure to the sector.

Investors in equities are already directly and indirectly significantly exposed to the property sector on top of home ownership. A major constituent of equity markets everywhere is financial institutions, including banks. Those banks obviously serve many functions, but a key one is the provision or facilitation of capital for the property markets. The banks do this both in the form of residential property markets, but also by financing and investing in commercial property. Even in the cases where the banks only act as a facilitator and pass on the principal risks to other investors (as opposed to other cases where banks hold on to a property investment), they still have a huge interest in a positive property market.

The bursting of the US sub-prime market bubble in 2007–08 and the subsequent default of many geared products connected to it was one of the primary drivers of the financial crisis. So even if the direct representation of property investment companies represents a fairly small portion of the overall stock market, we have indirect exposure to property through many other sectors of the stock markets. In addition to the banks, the listing of many large infrastructure and construction-related companies further adds to our indirect exposure to the property market because corporations in a wide variety of industries already are the largest holders of commercial property.3

Some might disagree that I’m leaving out property investments and I can appreciate why. For those investors who wish to add an investment in property, I would recommend you invest in low-fee and geographically-diversified property investment companies. A good option is publicly traded REITs (Real Estate Investment Trusts). REITs have a favourable tax treatment, particularly for US investors, and distribute most of the income from their diverse set of underlying property holdings (often mainly commercial, like offices and retail, but also warehouses, apartment buildings, hospitals, etc.).

If you do go ahead with adding property investments to your portfolio then consider the following:

- Invest broadly geographically and cheaply – there are some good global property ETFs (including one from iShares) that track the FTSE NAREIT Global index, or similar.

- Avoid concentrating in countries that you as an investor are already exposed to via your non-portfolio assets.

- Be clever about tax (REITs are tax-exempt from certain taxes); tax advantages could favour a larger allocation to property investments for some investors.

- When you consider adding property investments to the portfolio think hard about the exposure you already have to property, both indirectly via securities in your portfolio, but also potentially via your home.

Private equity, venture capital and hedge funds

I used to run a hedge fund in London and wrote a book about my experiences, Money Mavericks: Confessions of a Hedge Fund Manager (FT Publishing International, 2012), and still sit on the board of a couple of hedge funds. Also, earlier in my career, I worked at a private equity fund called Permira Advisors.

Private equity, venture capital and hedge funds (I will refer to them as alternative investments) do not belong in the rational portfolio.

All the alternative investment vehicles claim an edge in the market. They are essentially saying, ‘Give your money to us and we will provide you with a superior return profile.’ Time will tell if they are right or not, but by selecting them you are essentially saying that you yourself have an edge, not because you can make all the underlying investments yourself, but because you know someone who can, namely the manager of the alternative fund.

The perception of the alternative funds is often shaped by a couple of well-documented success stories. When John Paulson made billions for himself and his investors in 2008 from betting on a collapsing sub-prime housing market it was the kind of investment everyone wished that they had in their portfolio. Or when Sequoia Capital partners tell you that they have backed Apple, Cisco, Google, and other names you know too well the question almost turns into, ‘How can you not invest money in alternative funds?’

In many ways, the logic behind picking an alternative investment is like that of picking an active manager. You do it because you think someone is able to perform well when investing your money. While you may acknowledge that you can’t do so yourself, being able to pick an investment manager who can consistently outperform would be an incredibly valuable tool. But like stock picking it is a rare skill. Someone whose job it is to select alternative managers may say something like ‘the East Coast biotech sector will massively outperform over the next decade’, ‘I think convertible arb will be resurrected’, or ‘John Doe fund manager is just brilliant’. Rightly or not, these are not the kinds of statements an investor without an edge can or should make. Particularly when you consider that the liquidity of your investment in alternative funds can be so poor that you may not get your money back for years, the need for an edge and superior returns is further increased.

Fees are very high

Besides the fact that investing in alternatives suggests a claim of having an ‘indirect’ edge on the part of the investor, the funds are also typically very expensive.

Many alternatives charge an annual management fee of 1.5–2% in addition to a 20% share of all profits above a certain hurdle rate, plus other expenses. While hedge funds in particular, at times with great justification, claim that the return profile they create is very different from one you can get through the markets, the aggregate fees mean that only the best-performing funds will be worth their fees. And therefore only those who have an ability to consistently select the best funds should invest in these alternatives. Most people simply do not have this ability.

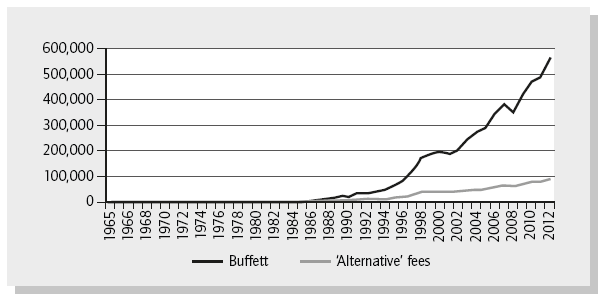

To get an idea of the magnitude of fees consider Warren Buffett, one of the most successful investors over the past generation. If Buffett’s fee structure had been that of a hedge fund instead of an insurance company the return to the investors would have looked very different (see Figure 9.4).

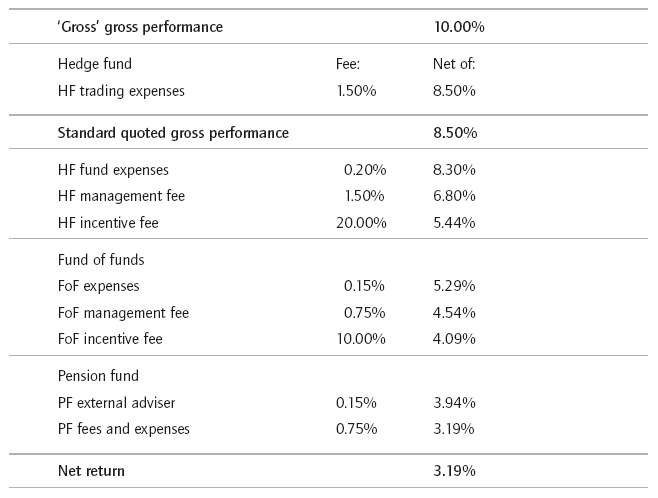

To illustrate the cumulative impact of fees, consider the example of a pensioner who invests money into a hedge fund through the normal route of a pension provider, via a fund of fund, with all the aggregate fees and expenses. Suppose further that the hedge fund made a return of 10% in a year, before any fees or expenses, and that it was a typical long/short fund with normal trading. What would be left for the pensioner once all the finance people had taken their bites? (See Table 9.2.)

Figure 9.4 $100 invested with Buffett versus one with an ‘alternative’ fee structure

Based on data from Berkshire Hathaway, www.Berkshirehathaway.com

This is, of course, before we have even asked how the hedge fund made its 10%. Was it because it simply had market exposure as it went up or was it all unique value added that could not be achieved elsewhere? If it was mainly because of markets going up, our pensioner has paid a shocking level of aggregate fees for exposure to the markets.

I’m not just picking on hedge funds: private equity and some structured products have as much to answer for. Despite similar fees they are unapologetically long the market often in a geared way: investors could do much better themselves through leveraged index trackers, and an investment in private equity is typically very illiquid. Be sure you get paid for the investment being illiquid, and that you don’t pay to be long the market – you can do that much more cheaply with an index tracker.

This is not to say that alternatives never make sense but rather that the high fees mean that the bar is very high indeed.

Alternative funds often argue that they provide investors with access to a different part of the economy (like a venture fund finding the next Facebook) or returns that are uncorrelated to the markets (like market neutral hedge funds). And they are sometimes right. Some alternative funds will undoubtedly do extremely well in future both in terms of providing investors with a unique exposure or just great returns, but the challenge is to select which one. Studies suggest that past performance is a poor guide to future returns so that doesn’t help us. (That would almost have been too easy – just pick the past winners and away you go!)

In addition to staying away from alternatives because picking the right alternative manager suggests an edge, many investors already have a lot of the same exposure that alternatives give, for all its high fees. The correlation between the returns of alternatives and the stock markets is quite high as the alternative funds often invest in assets similar to those represented by the stock markets. (Venture funds would argue that they invest in companies too small for stock exchanges, but they are still exposed to the same economy and exits often involve sales to large companies or initial public offerings (IPOs).) It is not arbitrary that 2008 was the worst year in the history of the alternative industry. In the rational portfolio you have many of the same exposures you would have as an investor in alternatives, but at about one-twentieth of the fees.

In summary

Stay away from alternative funds for the following reasons:

- Picking the right manager of an alternative fund requires an edge, which we don’t think we have.

- In the unlikely case that we could invest in all alternative funds and thereby get exposed to the whole sector, the combination of very high fees, poor liquidity of our investment, and the fact that we could have much of the same exposure but more cheaply through our stock market investment would render alternatives unattractive.

In reality, most investors couldn’t get access to the alternative funds if they wanted to. Ignoring the access products or share classes that some funds have, this is often because either the minimum investment size is too large (often $1 million or higher) or there are other regulatory obstacles. There is, however, a good chance that you are already exposed to them. Public and private pension funds are among the biggest investors in alternative funds. If you are a present or future recipient of benefits you are therefore already exposed to their performance. You just hope that whoever chose the alternative funds to invest in on your behalf has the required edge that eludes most of us.

Commodities

Before the 2008–09 crash, certain commodities performed very well and often became an integral part of well-diversified investment portfolios. While gold and oil perhaps dominated the broader media picture there were also other success stories.

Until fairly recently it was very hard for most investors to buy commodities. Unless you were an institutional investor set up to take possession of the physical commodities or trade the futures contracts it was a cumbersome process to gain direct exposure to the commodities. This difficulty has greatly been reduced over the past decades. Today there are ETFs available on a wide range of commodities and gaining the exposure is therefore as simple as buying a share in the ETF of your choice. Some of the most popular commodity ETFs are the gold ones, but there is a wide range of other commodities also available in addition to some that track broad-based commodity indices.

The economics of commodities are different from that of equities or bonds. To physically hold commodities we may actually incur a cost instead of necessarily expecting our ownership of them to generate cash in the future. There are storage and insurance costs to holding commodities. Furthermore, commodities are not income generating: the cost of extracting the commodity may change and the usefulness of that commodity in the production of goods may change, but nothing suggests that this will be consistently positive.

Although the costs of commodity trading for most investors have come down greatly it remains an expensive proposition for most. Even if we hold a commodity such as gold through an ETF we are still indirectly subject to the same storage and insurance costs, in addition to management and trading costs. Also, unless it is our profession to trade specific commodities there is a great chance that we are at a significant information disadvantage. If you trade oil and do so while working at Shell or BP there is a reasonable chance that you have an information edge compared to someone in their pyjamas trading on their computer at home. Make sure you are not in the latter group.

Financial investors in commodities mainly invest through futures. The futures market for all sorts of things is many centuries old, but the first organised exchange was created in Japan in the 1700s. This was so that samurais who were paid in rice at a future date could lock in the value they received. We can buy or sell a future on cocoa, grain, oil or whatever for months hence and avoid the issue of storage, delivery, etc. The price of the future will depend on the expectation of the future price of the commodity and the interest rate we can earn on the money in the interim. The futures contracts are settled through an exchange that ensures payment on expiry so that we don’t have to worry about the person or company we are buying our future from or selling it to.

But like the other asset classes we have discussed in this chapter, the main issue with trading commodities is the absence of an edge. Do you really have the knowledge or advantage in the market to profit from trading commodities? Chances are that you don’t unless you work in commodities and trade them for a living. If you don’t, don’t trade commodities.

As with property or alternatives, you already have a lot of commodity exposure through your portfolio of listed stocks. In the world stock market index are many mining or oil-related companies with large underlying direct exposures to commodities, and adding commodities to the portfolio would lead you to double up on the exposure. For example, if you were to buy oil in addition to owning it via all the oil companies in your equity index you would be adding to an already large exposure to that commodity, but it’s often hard to figure out exactly how much hedging commodity-related companies do themselves and what your indirect exposure to commodities from owning shares in a company therefore is.

Returns from commodities

Perhaps we could turn the question on its head and ask which commodities you would want to buy exactly and why you want to deselect others. If you buy cocoa beans, then why not wheat? If you buy copper, then why not iron scraps? Those that pick the individual commodities clearly claim an edge.

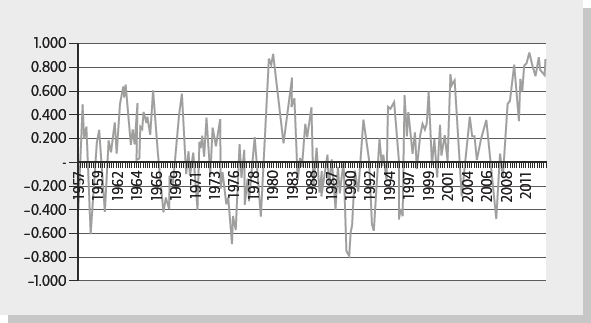

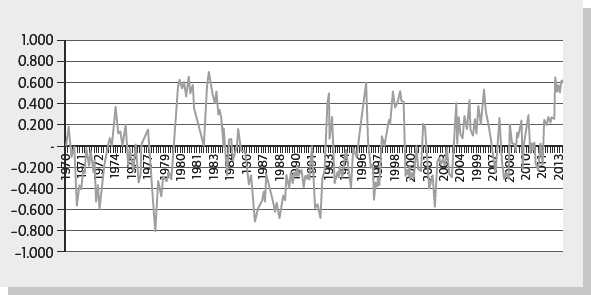

Investors in commodities claim that lack of correlation with the equity markets makes commodities attractive. One of the oldest commodity indices is the CRB Commodity index which tracks the performance of 22 commodities and first started tracking in 1957. Figure 9.5 shows the 12-month trailing correlation with the S&P 500 since inception.

As can be seen from the chart, commodities do indeed exhibit low correlation with the equity market, 2008 being a notable exception when they plummeted with equities. (The index was down 36% in 2008, rendering it a terrible hedge.)

But should we expect to make money from commodities?

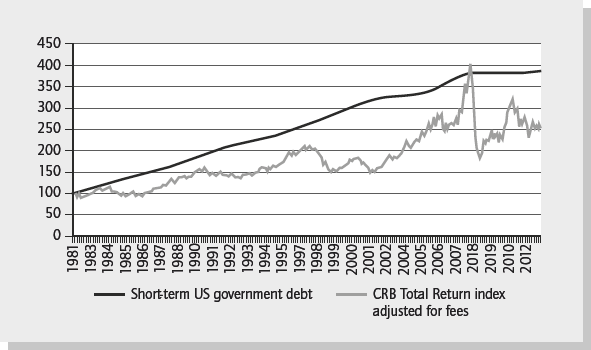

Spanning only a couple of decades, the organised price history4 of commodities is probably too short to be meaningful but Figure 9.6 shows a chart of the CRB Total Return index5 – this index was not created until the early 1980s – compared to an investment in US short-term bonds. This index does not include the implementation cost which I have included at 0.5% a year for the commodity index, more or less in line with current ETF costs.

It is not surprising that many advisers advocated investments in commodities until the crash of 2008. In the preceding decade, commodities had performed strongly with a history of low correlation to the equity markets. But you can’t get rich on low correlation; you need income and commodities are not income generating. Over the longer run, commodities trail the minimal risk rate of return and there is no reason to think that they will do so consistently in future. Because of that, and because you already have a lot of the same exposure through the existing portfolio, you should not include commodities in your rational portfolio.

Gold as a special case?

Gold has of course been a very public success story with the price per ounce well above $1,500, up from around $40 in the early 1970s when the US abandoned the gold standard. Gold does not have as much production use as some other metals and commodities, other than as jewellery and to some extent in electronics, but it has always been seen as a great preserver of value in times of distress.

If you want to avoid risk you should buy more of the minimal risk asset, and not buy gold. Gold is certainly not a low-risk asset – it is in fact very volatile in value. What attracts people to holding gold is the perception that it tends to move up in value when markets go down. It is therefore considered a hedge to the stock market or general economic/political turmoil.

I would caution you against viewing gold holdings as a hedge against stock market declines. If the stock market and the price of gold really moved in opposite directions (they do not – see Figure 9.7) and you had equal amounts invested in both, then in an economic decline you would make as much from the rise of gold as you would from the decline of the stock markets, and vice versa when markets were good. The only difference is that you would have paid expenses on your gold holdings as well as minor ones on your equity holdings. In that case you would have minimised your risk, but also your profits, and still be left with your expenses. Instead of having equity and gold exposures off-setting each other, you would have been better off just buying minimal risk bonds.

While the price of gold will continue to be volatile and perhaps even go up, as with the case of other commodities there is nothing intrinsic to suggest that gold as an investment will do better than the minimal risk rate, so I would suggest that you keep it out of your rational portfolio.

Private investments (or ‘angel’ investing)

In my personal life, the main way I differ from investing like the rational portfolio is through private investments. I’m incredibly lucky to have a group of talented friends and acquaintances who are doing very exciting things with their careers. Because of my background in hedge funds and finance, a large portion of this group is involved with finance, but certainly not all. Some are involved with various technology or related businesses. And quite frequently I’m approached to invest money as friends or acquaintances start something new or expand an existing business.

Private investments are perhaps an area of finance where we can slightly suspend the rational investment thinking. If you are approached by a friend to invest in his business you may have a lot of insight that other investors do not have. You know a lot about the principal and his history. You will also have heard him talk about the investment before he was trying to sell it to you so you have more of the real story. It could also well be that you are one of only a handful of people who was approached to invest money in the venture. As a result there is no real ‘market’ for the investment, but if there is then perhaps you are the investor with the most edge in that market. Since it’s essentially the presence of an active market for securities that leads to a price that we don’t think we can predict better, in the absence of that market there could be an opportunity for investing at favourable prices.

I was recently asked to put money into a New York-based private company that makes face recognition technology. A very snazzy presentation of how they will revolutionise social websites and everything else followed. The management team seemed very credible and knew the technology and the market very well. My main concern and reason I passed on the investment was that I felt that I was the one-thousandth person to be presented with the opportunity to invest. I also felt that most of the other 999 people who had passed on the investment were better positioned to gauge the viability of this company. This could be because they understood the technology or competition. Perhaps they could even write code and were able to look at the source code for the technology, which I can’t. There was also the issue of why they needed money from a London-based non-technical person in order to make a New York-based technology firm thrive – didn’t any of the locals want to do it? In short, I felt at a competitive disadvantage to others who had looked at but passed on the investment, and I did the same as a result. There was no edge.

There is unfortunately not a great amount of good and reliable data on private investments (outside the more institutional methods like venture capital, etc.). Many involved with private investments are notoriously bad at sharing performance data with the wider world. This is probably because many high-net-worth investors are reluctant to share information about their private portfolios, although exposure to the tax authorities may also play a role.

Poor information non-withstanding, according to a recent survey of studies on angel investing6 the average annual return to angel investors was 27.3%, which is obviously phenomenal. I would, however, suggest that there is an extremely heavy selection bias (only good results get reported, or people start reporting only after getting good results), and that if you had blindly invested in all angel deals the returns would have been substantially lower and perhaps fairly unimpressive. The report also states that 5–10% of the investments make most of the profits and the majority fail.

We all live in hope of being the first investor into the next Google or Facebook, but reality is probably far less glamorous. For most investors, making that investment has the probability of a lottery ticket even as many recount their near misses. But of course some people have become rich buying lottery tickets. I was president of the Harvard Club featured in the movie about Facebook (The Social Network) and knew people close to the founders. The endless ‘could have/would have/should have’ stories have inevitably followed.

Generally, and beyond the scope of this book, here are a few things to think about if you are considering potential private investments:

- Edge Are you in the analytical or informational position where you are the right person to be making this investment? A private investment may be a bit like buying a lottery ticket – a bad idea if you have average odds, but potentially interesting if you can better your odds somehow. But someone who is without an edge or advantage who blindly invested in every private deal that came her way would see a queue of people trying to take her money and would soon run out.

- Portfolio How does the investment fit in with your other assets? Would it tend to go wrong at the same time as everything else? Is it related to your job or area you live in? If you have several of them do they represent a substantial portion of your assets that may act similarly to each other?

- What do you invest? A lot of private investments become very time consuming in addition to the money invested. Are you getting paid for the time and expertise? Of course you may think it’s fun and could lead to future opportunities.

- Liquidity Private investments tend to be very illiquid and there will often be no ‘bid’ for your stake. At least for short-term financial planning you should probably treat a private investment as ‘dead’ money.

- High failure rate There may only be a 5–10% success rate in angel/private type deals. While the pay-out in case of success may be great you should be ready to lose the entire investment. Think about how this extremely high risk/return profile will affect your portfolio and investing life in general.

If you overcome some of the issues involved in making private investments there are some potential great advantages including:

- There are often tax advantages to private venture-type investing, particularly in development or clean tech sectors. Use them!

- You can use your expertise and skillset to add to your profits.

- Depending on the investment there are potentially large pay-outs that an investor investing in broad indices will not have in general (markets don’t go up 100 times). In a book that is extremely anti-get-rich-quick, for the lucky/skilful few, private investments can offer the rare exception.

- If private investments are not dependent on general economic conditions, etc. they may be a good diversifier to the rest of your portfolio where the various assets will generally be correlated.

- If you make a private investment, despite being a rational and cautious investor, you will probably only do so after long study and serious consideration. This will probably serve you well. Good luck!

Collectibles

Occasionally there will be news about the sale of a painting for an eye-watering sum, triggering a discussion about collectibles as an investment. Collectibles can mean lots of things, but often include art, coins, vintage cars, antiques, coins and stamps – but also esoteric things like sports memorabilia, books or netsuke.7

The issue with collectibles as a financial investment is that it is hard to buy an index type of exposure to a broad range of them. You can’t typically buy one-thousandth of a Renoir painting, only the leg of an antique chair or a sip of a fine wine. You are forced to pick individual items. If you are a great expert in a collectibles field then that may be a profitable venture, but if you are not, then chances are it is a losing proposition even if in some places there are tax benefits from owning art. You can, of course buy shares in fund-like structures, but even these only buy a small sub-set of the market.

While there are certain indices that suggest that art has been a great investment,8 they suffer from a few shortcomings. For one, the studies often focus on segments of the art world that have been successful, suggesting selection bias, and are typically not easily replicable, so gaining exposure to them is not feasible. Also, many indices and the past performance of collectibles ignore the large transactional costs, insurance and storage costs. When you include all of these costs the return from collectibles is far less obvious, and you should not include them in the financial part of your portfolio.

There are, of course, non-economic reasons for buying collectibles. On top of the hope for a financial return, investors in a painting could derive great value from looking at it or reading a first edition book. Similarly, a stamp collector or someone driving in vintage car rallies may derive great pleasure or prestige from ownership. On a larger scale who had heard of Roman Abramovich or Mansour bin Zayed (owner of Chelsea and Manchester City football clubs respectively) before they bought their clubs? I don’t think either expects to make money from ownership. Their objectives were perhaps prestige and having fun, both achieved in abundance if you ask me. And to that end they have spent the equivalent amount of their net worth to that of an average person buying a bicycle.

The non-economic benefit from owning collectibles obviously depends greatly on the individual and is very hard to quantify. Since most people gain some non-economic benefit from owning the asset, if you are purely a financial investor you will probably be disappointed. Perhaps a better way to think about collectibles is to be sure that you collect something you enjoy and that you are at least a reasonable expert. Combining the financial and non-economic gain from the investment may make it a worthwhile undertaking.

1 Although I would generally caution you against leverage, a mortgage on your property is often the cheapest form of leverage you can get, both because of tax advantages, but also because lenders are willing to lend you money at good rates against a fixed asset like your property. So if you need to borrow money and can do it through your property then that may be the cheapest way.

2 Although the quoted property investment companies that are represented in the index trackers only represent a small proportion of the value of the world’s total property that is also true of many other industries. Also, if this small quoted representation of property holding suggested that those quoted were extra attractive we would trust the market to have this reflected in the share price relative to other securities.

3 According to Richard Ferri’s excellent book All About Asset Allocation (McGraw-Hill Professional, 2010) about two-thirds of the total value of commercial property in the US is owned by corporations, many of which you are already invested in through the general equity market index.

4 There is obviously a millennia-long price history of commodities, but to my knowledge not in an aggregated index that can be replicated in financial products like ETFs or mutual funds.

5 The total return index includes interest on the ‘free’ cash when investing in futures. The collateral on a futures contract is typically 5–10%, leaving 90–95% of capital free to be invested. The assumption is that this money is invested in treasury bills.

6 ‘Historical Returns in Angel Markets’ by David Lambert from Right Side Capital Management www.growthink.com/HistoricalReturnofAngelInvestingAssetClass.pdf.

7 The Hare with Amber Eyes by Edmund de Waal traces the history of a family netsuke collection through a century of tumult. Perhaps far-fetched, but a lesson from the book is how the netsuke maintain monetary and emotional value as the world collapses around them.

8 See for example www.artasanasset.com