98 Joint Cognitive Systems

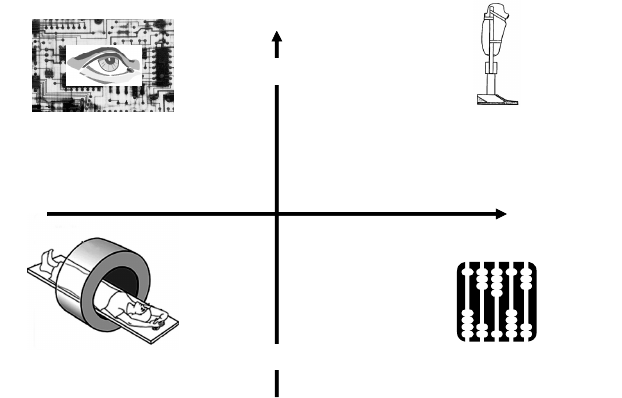

In Figure 5.3, four characteristic artefacts are used to illustrate the

meaning of the dimensions. A decision support system, and in general any

system that provides a high level of complex functionality in an automated

form, illustrates a hermeneutic relation and a high degree of exchangeability

– i.e., a prosthetic relation. While decision support systems (e.g., Hollnagel,

Mancini & Woods, 1986) are supposed to help users with making decisions,

they often carry out so much processing of the incoming data that the user

has little way of knowing what is going on. In practice, the user’s decision

making is exchanged or substituted by that of the DSS, although this may not

have been the intention from the start.

Transparency

Exchangeability

Decision support system

Computer tomography

Artificial limb

Abacus

Prosthesis

ToolTool

Hermeneutic

Embodiment

Figure 5.3: The transparency-exchangeability relation.

An artificial limb, such as a prosthetic arm or leg, represents an artefact,

which on the one hand clearly is a prosthesis (it takes over a function from

the human), but at the same time also is transparent. The user is in control of

what the prosthesis does, even though the functionality need not be simple.

(A counterexample is, of course, the ill-fated Dr. Strangelove.) The issue

becomes critical when we consider a visual prosthesis that allows a blind

person to see, at least in a rudimentary fashion. Such a device certainly

produces a lot of interpretation, yet it does not – or is not supposed to –

provide any distortion. Indeed, it is designed to be transparent to the user,

who should ‘see’ the world and not the artefact.

Computerized tomography (CT), or computerized axial tomography

(CAT), as well as other forms of computer-enhanced sensing, illustrate

Use of Artefacts 99

artefacts with a hermeneutical relation, yet as a tool, i.e., with low

exchangeability. Computer tomography is a good example of extending the

capability of humans, to do things that were hitherto impossible. CAT, as

many other techniques of graphical visualisation – including virtual reality –

are seductive because they provide a seemingly highly realistic or real picture

of something. In the case of CAT there is the comfort that we know from

studies of anatomy that the underlying structure actually looks as seen from

the picture. In the case of research on subatomic particles – such as the hunt

for the Higgs’ boson – or in advanced visualisation of, e.g., simulation results

and finite element analysis, the danger is considerably larger, hence the

hermeneutic relation stronger, because there is no reality that can be

inspected independently of the rendering by the artefact. Indeed, one could

argue that the perceived reality is an artefact of the theories and methods.

The final example is an abacus. The abacus is highly transparent and for

the skilled user enters into an embodiment relation. The human calculator

does not manipulate the abacus, but calculates with it almost as a

sophisticated extension of hand and brain. Similarly, the abacus is clearly a

tool, because it amplifies rather than substitutes what the user can do. The

human calculator is never out of control, and the abacus – beings so simple –

never does anything that the user does not.

Range of Artefacts

As the example of getting up in the morning showed we are immersed in a

world of artefacts, some of which are our own choosing while others are not.

For CSE it is important to understand how artefacts are used and how JCSs

emerge. For this purpose it is useful to consider several ranges of artefacts:

simple, medium, and complex.

The simple artefacts are things such as overhead projectors, household

machines, doors, elevators, watches, telephones, calculators, and games.

They are epistemologically simple in the sense that they usually have only

few parts (considering integrated circuits as single parts in themselves), and

that their functions are quite straightforward to understand, hence to operate.

(Newer types of mobile phones and more advanced household machines may

arguably not belong to this category, but rather to the next.) This means that

they are tools rather than prostheses in the sense that people can use them

without difficulty and without feeling lost or uncertain about what is going to

happen. Indeed, we can use this as a criterion for what should be called a

simple artefact, meaning that it is simple in the way it is used, typically

having only a single mode of operation, rather than simple in its construction

and functionality. (Few of the above mentioned artefacts are simple in the

latter sense.) Indeed, much of the effort in the design of artefacts is aimed at

making them simple to use, as we shall discuss below.

100 Joint Cognitive Systems

Medium level artefacts can still be used by a single person, i.e., they do

not require a co-ordinated effort of several people, but may require several

steps or actions to be operated. Examples are sports bikes (mountain bikes in

contrast to ordinary city bikes), radios, home tools, ATMs – and with them

many machines in the public domain, VCRs, personal computers regardless

of size, high-end household machines, etc. These artefacts are characterised

by having multiple modes of operation rather than a single mode and in some

cases by comprising or harnessing a process or providing access to a process.

They may also comprise simple types of automation in subsystems or the

ability to execute stored programs. In most cases these artefacts are still tools,

but there are cases where they become prostheses as their degree of

exchangeability increases.

Finally, complex artefacts usually harbour one or more processes,

considerable amounts of automation, and quite complex functionality with

substantial demands to control. Examples are cars, industrial tools and

numerically controlled machines, scientific instruments, aeroplanes,

industrial processes, computer support systems, simulations, etc. These

artefacts are complex and more often prostheses than tools, in the sense that

the transparency certainly is low. Most of them are associated with work

rather than personal use, and for that reason simplicity of functioning is less

important than efficacy. Usually one can count on the operator having some

kind of specific training or education to use the artefact, although it may

become a prosthesis nevertheless.

Cognitive Artefacts

It has become common in recent years to refer to what is called cognitive

artefacts. According to Norman (1993), cognitive artefacts are physical

objects made by humans for the purpose of aiding, enhancing, or improving

cognition. Examples are sticker-notes or a string around the finger to help us

remember. More elaborate definitions point to artefacts that directly help

cognition by supporting it or substituting for it.

Strictly speaking, the artefacts are usually not cognitive – or cognitive

systems – as such, although that is by no means precluded. (The reason for

the imprecise use of the term is probably due to the widespread habit of

talking about ‘cognitive models’ when what really is meant is ‘models of

cognition’ – where such models can be expressed in a number of different

ways.) There is indeed nothing about an artefact that is unique for its use to

support or amplify cognition. A 5-7000 year old clay tablet with cuneiform

writing is as much an artefact to support cognition as a present day expert

system. Taking up the example from Chapter 3, a pair of scissors may be

used as a reminder (e.g., to buy fabric) if they are placed on the table in the

hall or as a decision aid if they are spun around.

Use of Artefacts 101

Consider, for instance, the string around the finger. Taken by itself the

string is an artefact, which has a number of primary purposes such as to hold

things together, to support objects hanging from a point of suspension, to

measure distances, etc. When a piece of string is tied around the finger it is

not used for any of its primary purposes but for something else, namely a

reminder to remember something. Having a string tied around the finger is

for most people an unusual condition and furthermore not one that can

happen haphazardly. Finding the string around the finger leads to the

question of why it is there, which in turn (hopefully) reminds the person that

there is something to be remembered. In other words, it is a way to extend

control by providing an external cue.

The use of the string around the finger is an example of what we may call

exocognition or the externalisation of cognition. Rather than trying to

remember something directly – by endocognition or good old-fashioned

‘cognition in the mind’ – the process of remembering is externalised. The

string in itself does not remember anything at all, but the fact that we use the

string in a specific, but atypical way – which furthermore only is effective

because it relies on a culturally established practice – makes it possible to see

it as a memory token although not as a type of memory itself.

We may try to achieve the same effect by entering an item, such as an

appointment, into the to-do list of a personal digital assistant (PDA) or into

the agenda. In this case the PDA can generate an alert signal at a predefined

time and even provide written reminder of the appointment. Here the PDA is

more active than the piece of string, because it actually does the

remembering; i.e., it is not just a cue but the function in itself. The PDA is an

amplifier of memory, but it only works if there is someone around when the

alert is generated. Relative to the PDA, the piece of string around the finger

has the advantage of being there under all conditions (until it is removed, that

is). Neither the string nor the PDA is, however, cognitive in itself –

regardless of whether we use the traditional definition or the CSE

interpretation. Speaking more precisely, they are artefacts that amplify the

ability to control or to achieve something or which amplifies the user’s

cognition, rather than cognitive artefacts per se. As such they differ in an

important manner from artefacts that amplify the user’s ability to do physical

work, to move, to reach, etc., in that they only indirectly strengthen the

function in question.

The Substitution Myth

It is a common myth that artefacts can be value neutral in the sense that the

introduction of an artefact into a system only has the intended and no

unintended effects. The basis for this myth is the concept of

interchangeability as used in the production industry, and as it was the basis

102 Joint Cognitive Systems

for mass production – even before Henry Ford. Thus if we have a number of

identical parts, we can replace one part by another without any adverse

effects, i.e., without any side-effects.

While this in practice holds for simple artefacts, on the level of nuts and

bolts, it does not hold for complex artefacts. (Indeed, it may not even hold for

simple artefacts. To replace a worn out part with a new means that the new

part must function in a system that itself is worn out. A new part in an aged

system may induce strains that the aged system can no longer tolerate.) A

complex artefact, which is active rather than passive, i.e., one that requires

some kind of interaction either with other artefacts or subsystems, or with

users, is never value neutral. In other words, introducing such an artefact in a

system will cause changes that may go beyond what was intended and be

unwanted (Hollnagel, 2003).

Consider the following simple example: a new photocopier is introduced

with the purposes of increasing throughput and reducing costs. While some

instruction may be given on how to use it, this is normally something that is

left for the users to take care of themselves. (It may conveniently be assumed

that the photocopier is well-designed from an ergonomic point of view, hence

that it can be used by the general public without specialised instructions. This

assumption is unfortunately not always fulfilled.) The first unforeseen – but

not unforeseeable – effect is that people need to learn how to use the new

machine, both the straightforward functions and the more complicated ones

that are less easy to master (such as removing stuck paper). Another and

more enduring effect is changes to how the photocopier is used in daily work.

For instance, if copying becomes significantly faster and cheaper, people will

copy more. This means that they change their daily routines, perhaps that

more people use the copier, thereby paradoxically increasing delays and

waiting times, etc. Such effects on the organisation of work for individuals,

as well as on the distribution of work among people, are widespread, as the

following quotation shows:

New tools alter the tasks for which they were designed, indeed alter

the situations in which the tasks occur and even the conditions that

cause people to want to engage in the tasks. (Carroll & Campbell,

1988, p. 4)

The substitution myth is valid only in cases where one system element is

replaced by another with identical structure and function. Yet even in such

cases it is necessary that the rest of the system has not changed over time,

hence that the conditions for the functioning of the replaced element are the

original ones. This is probably never the case, except for software, but since

there would be no reason to replace a failed software module with an

identical one, the conclusion remains that the substitution myth is invalid.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.