Chapter 1: Introduction

Introduction

In my freshman year in college, I started work on my first intranet application. The files in the main directory of the partially functioning application looked something like Figure 1-1.

Looking at the file names in this directory, you can see that I used some very similar names, such as exam.php, exam1.php and examfile.php. The purpose of that naming convention was to create new versions of my application without losing the old, working logic—in case the new ideas failed! I assumed that, because I understood what each of those files did, it should be fine to have a bunch of similarly named files.

However, there were two flaws in that thinking. Firstly, anyone else examining this code wouldn’t be able to make sense of this mess. Secondly, after a few months, even I was struggling to recall what each version of these files was for. Clearly, I needed a better system for managing the various versions of my files.

If I had this much trouble working on a small, personal project, imagine how difficult it must have been for larger software projects, with thousands of files and contributors distributed all over the world! Developers once used emails to coordinate changes among team members. When they made changes to a project, they would each create a “diff” file with all their changes and email it to the lead developer, who would incorporate them into the project if everything worked properly.

When you’re working on the same files as other developers, keeping track of what you’ve changed and trying to merge it with work done by your peers becomes very difficult. It can result in a lot of confusion and time wasting.

Imagine another situation, where you’re working on an idea and your boss wants to see what you’ve already completed. Ideally, you’d want to be able to do the following:

- stash away the changes and revert to the last stable state

- show your boss the latest completed work

- resume your work with the current state once that’s done

All of the situations I’ve described above give rise to the need for what’s known as “version control”. So let’s find out what that is.

Version Control

Version control (or revision control) is a system that records changes to a file or a group of files and directories over time, so that you can review or go back to specific versions later. Over the course of this book, I’ll demonstrate how this works. But first, let’s examine in more detail what version control is.

Quite literally, version control means maintaining versions of your work—perhaps most commonly in the form of source code, though it can be used for other kinds of work too. You may like to think of version control as a tool that takes snapshots of your work across time, creating checkpoints. You can return to those checkpoints any time you want. Not only are the changes recorded in these checkpoints, but also information about who made the changes, when they made them, and the reasons behind the changes.

I’ve already mentioned the first objective of version control—to back up and restore. Version control eliminates the need to create backup files like I was doing in my college days (that is, endless duplicates with different names). Version control also gives you the ability to return to previous states of your work without losing the current state.

Version Control Doesn’t Replace the Need for a Regular Backup Solution

The word “backup” above, as noted, refers to the process of creating multiple copies of the same file. Git removes the need for that. However, this is different from regularly backing up your files to an external source—such as a portable drive or cloud storage—to ensure you don’t lose anything following a disk failure.

Next, version control lets you synchronize your work with peers who are working on the same projects. In other words, it enables you to collaborate with others without the possibility of someone’s changes overwriting someone else’s work accidentally.

Version control also tracks changes to a project and other data associated with the changes. It makes the process of debugging your code easy too, which we’ll explore in some detail.

Conflicts in files can also be resolved through version control—such as when multiple people have made changes to a file that clash. A version control system highlights the conflicts and provides an opportunity to fix them.

Yet another feature of version control is that it enables work on multiple features of a project at the same time. This gives great scope for experimentation, trial and error. Each feature can be developed independently of the others, and can easily be removed if it doesn’t work out.

Now that you’ve been introduced to the concept of version control, let’s look at how we may already be using version control in our daily lives.

Examples of Version Control in Daily Life

You’ve probably visited the Wikipedia site at some point. You may even have taken the opportunity to update its content, too—as we’re all invited to do. When editing a page, you may also have checked its history. That’s where things get really interesting.

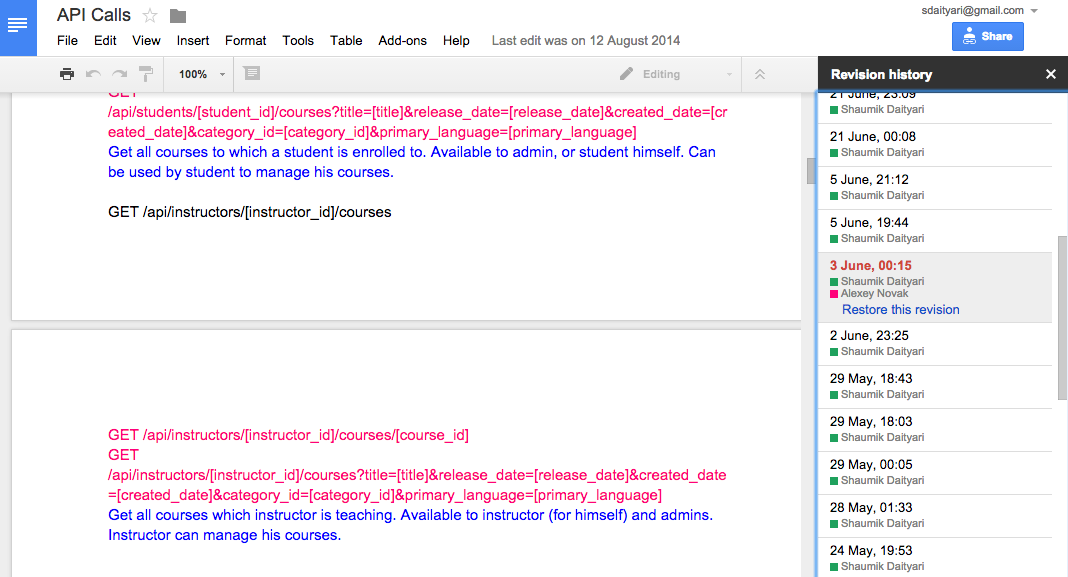

The history page shown in Figure 1-2 lists changes to that page. It also records the time of the change, the user who made it, and a message associated with the change. You can examine the complete details of each edit, and even revert back to an older version of the page. This is a good example of a simple form of version control.

Google Docs provides another example of version control that you might experience in daily life. If you check the revision history of a file in Google Docs, shown the figure above, you’ll notice that Google saves the state of your file after every few changes. You can preview the status of the document in any of those previous states—and choose to revert back to it, if needed.

Version Control Systems: the Options

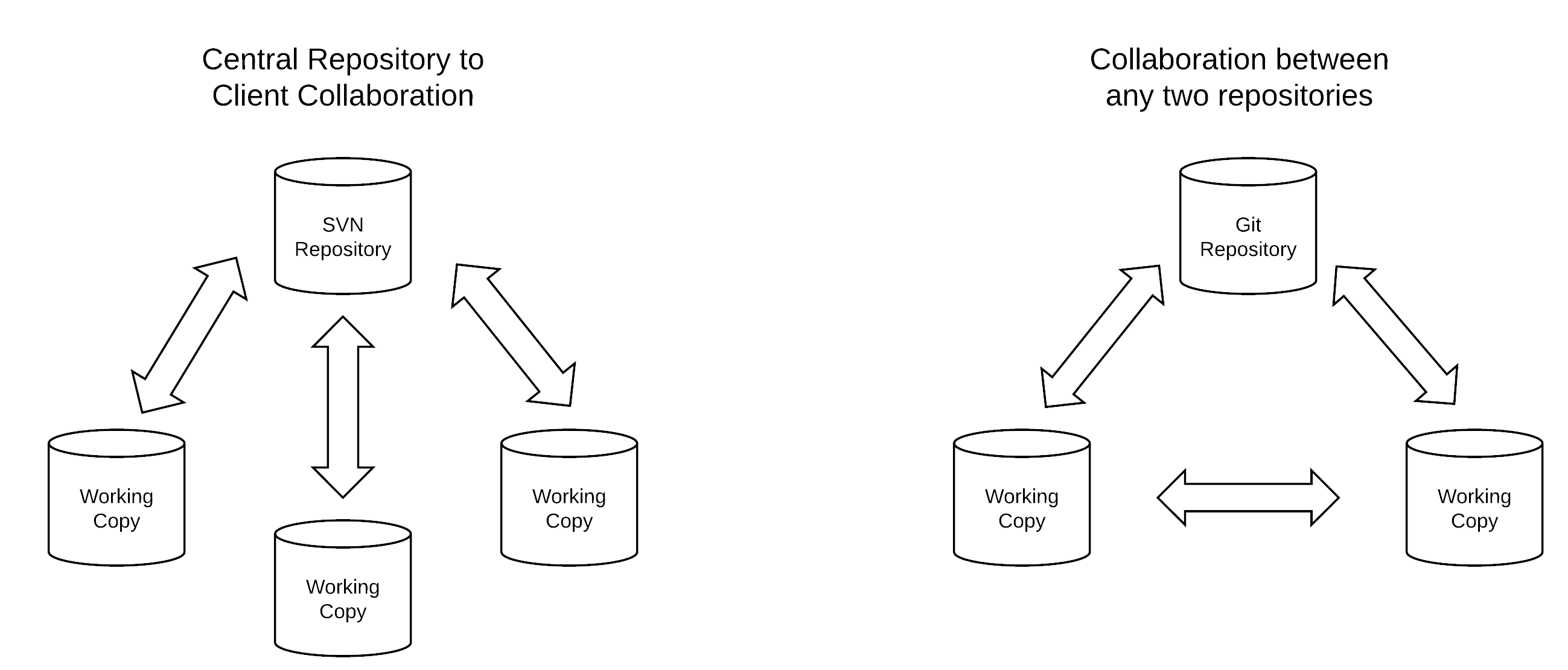

There are two types of version control systems (VCS), known as “centralized” and “distributed”.

Centralized systems have a copy of the project hosted on a centralized server, to which everyone connects to in order to make changes. Here, the “first come, first served” principle is adopted: if you’re the first to submit a change to a file, your code will be accepted.

In a distributed system, every developer has a copy of the entire project. Developers can make changes to their copy of the project without connecting to any centralized server, and without affecting the copies of other developers. Later, the changes can be synchronized between the various copies.

In the earliest version control systems, files were tracked only locally, and only one person could work on a file at a time. Examples of these include Source Code Control System (SCCS) and Revision Control System (RCS), which were common in the 1970s and 1980s.

The next step forward was the introduction of client-server version control systems, which enabled multiple authors to work on the same file (although some still worked on the first come, first served basis). Examples of such systems include Concurrent Versions System (CVS) and Subversion, which are still in use today.

Since around 2005, distributed systems have gained widespread acceptance, with the emergence of systems such as Git, Mercurial and Bazaar.

VCS Is Not CVS

Don’t confuse the abbreviations VCS (version control system) and CVS (concurrent versions system). CVS is just one of the many kinds of VCS.

Back in my freshman year, version control systems were available. However, in the example of my small project, I didn’t use one, simply because I was a beginner and didn’t know they existed. Many people first get introduced to version control systems when they start working with a team. Nowadays, most people get the first taste of version control when dealing with open-source projects.

Enter Git

This book is about Git, a distributed version control system. Git tracks your project history, enabling you to access any version of it back in time. It also allows multiple people to work on the same project, helping avoid confusion when more than one person tries to edit the same file.

Git was created by Linus Torvalds (who is also known for the Linux kernel), and Junio Hamano is its primary developer. Git, as described on the Git website, is a source code management (SCM) solution, but essentially it’s just a type of version control system.

The primary objective behind Git was to implement and design a version control system that was distributed, reliable and fast. While working on Linux, Torvalds needed a version control system to manage the Linux codebase. BitKeeper was a distributed system at that time, but Torvalds believed that, although BitKeeper was a good option, being a commercial product made it unsuitable for the development of an open-source project like Linux.

Torvalds had three criteria for a version control system: it had to be distributed, efficient and safe from corruption. There was no open-source, distributed version control system in the mid 2000s that could satisfy all these conditions. Hence, Git was developed out of necessity.

Git’s Philosophy

Torvalds once explained in a Google Tech Talk his reasons for creating Git. He has very strong views on the subject of version control, and I suggest you go through the talk once to understand the philosophy of Git. In this talk, Torvalds explains that he came up with the name Git because he believes the silliest names are our best creations. However, I recommend that you only watch the talk after you’re comfortable with the basic Git operations, as it’s not a tutorial: it’s aimed at users who have some knowledge of Git or other version control systems.

Advantages of Distributed Version Control Systems

Torvalds insisted on a distributed system because of the independence it affords to developers. With a distributed system, you can work on your copy of the code without having to worry about ongoing work on the same code by others. What makes it even better is that any distributed copy of the project can contain all the history of the project. A distributed system also lets you work offline, meaning you can make changes without having access to the server that stores the central repository.

Another advantage of distributed systems is that you can sync your repositories among yourselves, bypassing the central location. Let’s say the access to the main server goes down and you have to collaborate with a colleague. You can share changes with your colleague and continue to work on the project together, and then later push all your changes to the location everyone has access to.

In a centralized system, anyone who makes a change needs to be given access to the central location. In contrast, in a distributed system, new developers can make changes to their own repositories without being granted write access, while more experienced contributors can be given write access and the ability to review other contributions before merging them into the repository. Managing access is easier in distributed systems.

Git and GitHub

Since its creation, Git has become immensely popular—not only due to its own merits and the fact that Torvalds created it, but also because of the popular code sharing site GitHub.

People often confuse Git and GitHub, but they are quite different things. GitHub provides services that are related to Git. It’s a website that helps you manage Git-controlled projects.

GitHub allows users to put their Git repositories on the cloud, and to perform Git-based operations through a web interface. It also provides desktop and mobile apps that offer the same services. GitHub was launched a few years after Git, and remains very popular among enthusiasts of open source.

There are many other websites like GitHub, such as Bitbucket and GitLab. GitHub and Bitbucket are cloud-based solutions, but GitLab allows you to set up this functionality on your own servers. Other, similar services have come and gone, but these options have remained popular over the last few years. We’ll explore these code sharing websites in a later chapter, and discuss how you can make use of them.

Conclusion

What Have You Learned?

- What is version control?

- How do we unknowingly use version control in our lives?

- What are the types of VCS?

- What is Git? What are its capabilities?

What’s Next?

Now that we have a basic concept of what a version control system does, let’s get our feet wet with Git. In the next chapter, we’ll look at how to install Git and use it in a project.