CHAPTER

7

DEVELOP PERIPHERAL VISION AND SEE WHAT OTHERS MISS

Leadership often demands bold moves—an industry-altering acquisition, a major investment in an innovative technology, the opening of a new regional market, a wide-ranging reorganization. The best leaders use both hard and soft data to improve the quality of their decisions in such areas. This requires that they take advantage of the views of others, especially those who are in the best position to assess the consequences of a particular course of action, as well as to point out a leader's potential blindspots or biases. The challenge, in part, is getting these people to be direct and clear in expressing their concerns. For a variety of reasons, individuals often communicate in subtle or even misleading ways to those above them. Effective leaders create a culture that promotes straight talk but also pay attention to the nuances of communication in the decision-making process. This is particularly true for hard-charging executives who have an almost singular focus on driving their organizations forward and making decisions quickly.

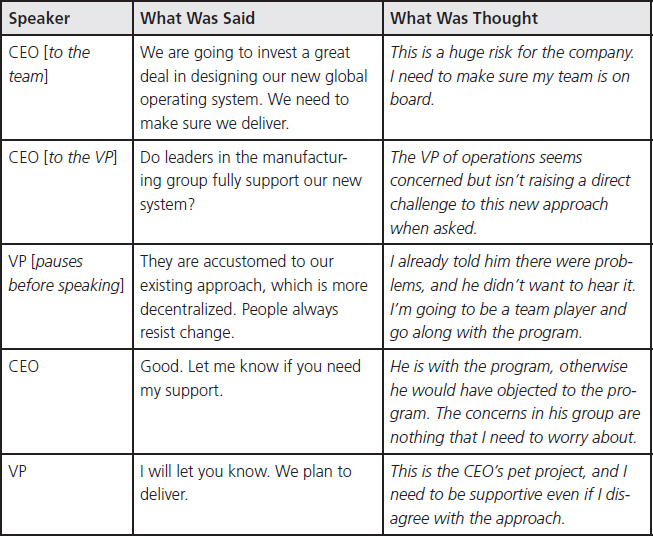

The previous table displays a dialogue that took place during a leadership team meeting between a leader seeking to determine whether he has a problem with a new global manufacturing process and his vice president of operations. In this exchange, the CEO and VP talked past one another. The CEO was consequently unaware of the severity of the problems he was facing with his new initiative and moved forward when he should have delved more deeply into the issue. The new processes subsequently failed to hit implementation milestones and deliver on his expectations. From the CEO's perspective, he gave the VP an opportunity to voice any concerns and the VP failed to do so. The leader, with some justification, felt blindsided. From the VP's perspective, he tried to warn the CEO but he was not truly listening and didn't want to hear any further objections. The VP felt the CEO was set on pushing forward and that voicing concerns was a wasted effort.

Leaders must strive to create a culture that promotes straight talk but also pay attention to the nuances of communication in the decision-making process.

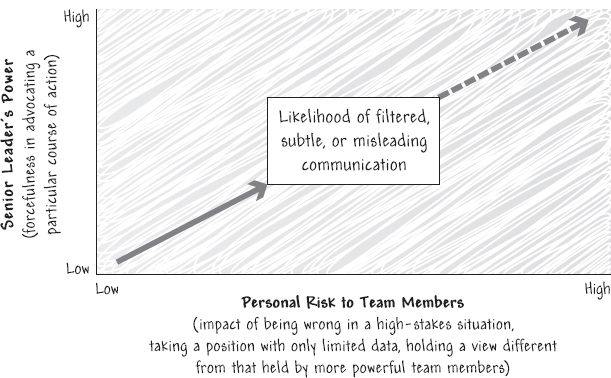

In some cases, those at the top of an organization and those at lower levels participate in an unspoken collusion with the goal of avoiding conflict. Leaders typically want to be seen as being right and have their preferred course of action accepted. Most also have healthy egos and confidence in their own capabilities. At the same time, some people at the next levels of management have a desire to please those above them. They want to avoid potential embarrassment if proven wrong and are also cautious about going up against a more powerful figure who will influence their careers. Consequently, concerns about a particular course of action are often expressed in subtle ways that are easily missed by those at the top. In more extreme cases, people will simply tell the leader what they think he or she wants to hear. The choreography of these interactions is interesting to watch. Part of the routine (whether you are the leader or an individual at the next level) is to appear as if you are not engaging in the routine. This pattern of distortion often increases as a leader becomes more powerful in an organization, setting up the conditions for restricted information flow and less effective decision making.

The result is that those who are less powerful keep important but negative information to themselves or position it in a manner that makes it less objectionable to those in positions of greater power. Leaders, in turn, don't fully appreciate what is being distorted because the power dynamic in most organizations is such that these issues are undiscussable—at least with the leader. In other words, people don't typically go to the leader and say, “You say you want open discussion but your behavior suggests otherwise. Therefore, I will not tell you what I am truly thinking in our team meetings.” As a result, the leader operates with flawed or incomplete information and, more important, doesn't know that he or she is operating with flawed or incomplete information—resulting in blindspots. (The dynamics of this situation are summed up in the following graphic, “Communication Distortions.”)

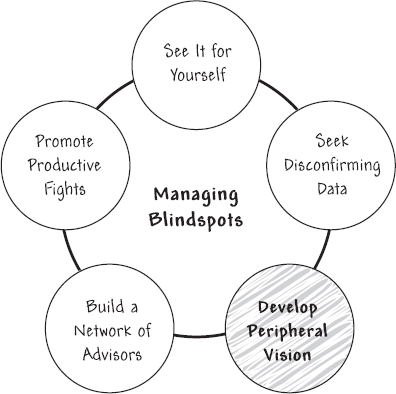

Solving problems is sometimes easier for a leader than identifying the problems that must be solved.1 I use the term peripheral vision to refer to a leader's ability to recognize warning signs of problems that need to be addressed before they escalate into major issues.2 Information regarding problems is often subtle, easily lost in the myriad of data and issues that come in front of a leader. Some call these warning signs weak signals, because they are obvious to most only in retrospect as people look for answers to the question, “What went wrong?” The resulting failures, in some cases, occur rapidly—the warning signals are there but the leader doesn't see or interpret them accurately. The collapse of Barings Bank, where the suspicious actions of a rogue trader were overlooked by headquarters staff, is one such case. The Columbia shuttle disaster is another example of a leader not following up on warning signals that she viewed as being unimportant. Or failures can occur more slowly. GM, under Roger Smith's tenure, had a number of warning signs that Japanese manufacturers were slowly and systematically capturing market share with superior products—but these warnings, particularly early in the ascent of Toyota, Honda, and Nissan, were largely ignored by Smith and his leadership team at GM.

Communication Distortions

The ability to see weak signals varies among individuals. I worked with one leader who was skillful at noting subtle warning signs that others often missed. Once, for instance, he was making a proposal to the senior leadership team of his large multinational firm. One of his peers had concerns about his recommendations but did not say anything in the meeting. He noted to himself, however, that she was quiet and made a point to meet with her after the meeting—thinking that her silence was an indication that she had concerns but didn't want to discuss her views in the group. She confirmed after the meeting that she had issues with his proposal but didn't want to surface them in the meeting because of the political nature of the group and the coalitions within it that made open discussion difficult. The two of them worked through her concerns in their private discussion, and he gained the support he needed to move forward. To his credit, he was paying attention in the meeting to the subtle behavior of a key peer and was skillful at managing the dynamic to achieve what he needed. A less skillful leader would have overlooked her behavior or would have noted her silence and asked her in the meeting if she had any concerns (resulting in a discussion that she didn't want to have).

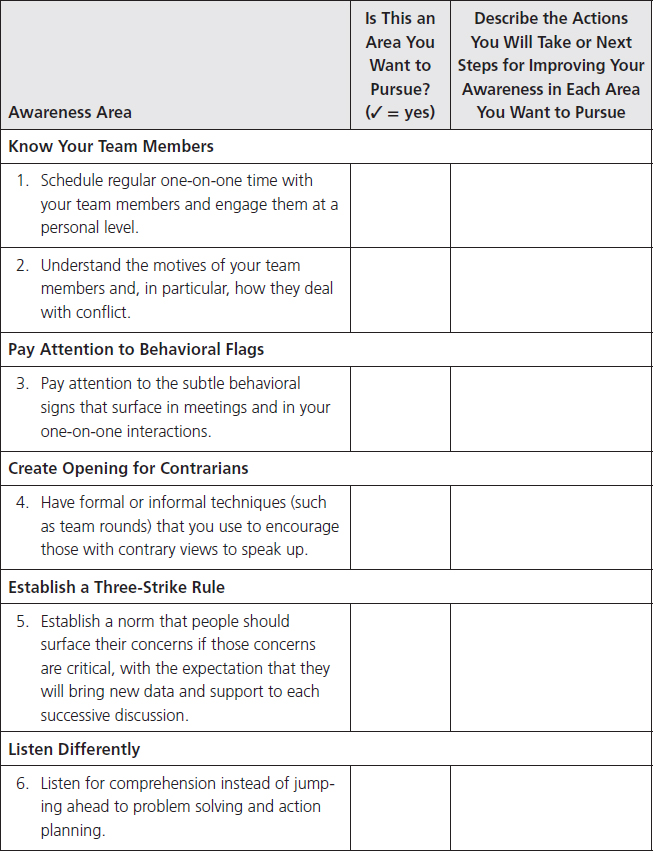

Several actions are important for the leader who wants to develop peripheral vision; they are

- Know your team members.

- Pay attention to behavioral flags.

- Create openings for contrarians.

- Implement a three-strike rule.

- Listen differently.

KNOW YOUR TEAM MEMBERS

The senior leader needs to get to know his or her team in depth in order to determine how to best interpret the subtleties of team member behavior. Differences in team members' decision-making and influence styles are particularly important. Some team members are comfortable with letting events unfold, while others prefer to resolve issues quickly. Some like to collect and analyze a wealth of data before making a decision, while others rely more on their intuition. Team members also differ in their willingness to challenge those in positions of authority, particularly in public settings—some will do so openly and forcefully, while others will do so only with trepidation and primarily outside of group meetings.

Knowing how to “read” team members includes having not only an awareness of each person's tendencies but also an awareness of deviations from his or her typical approach. Some team members are inclined to examine every side of an issue before making a decision. In a few situations, however, these same individuals will appear to see only one side of an argument. When this occurs, the leader needs to understand why a team member's stance is different from his or her usual approach. Similarly, some team members are typically more comfortable with risk than others are. When these risk-friendly members oppose a new idea that other members support, the leader needs to take note and seek to understand their concerns. The challenge is for the leader to remain focused on the decision that needs to be made while simultaneously paying attention to subtleties that can easily be lost in the heat of debate.

A leader also needs to be aware of his or her dominant style, and how it influences decision making in a team. Take the leader who values efficiency and conducts meetings in a disciplined manner (with clear objectives, rigid time management, and so forth). She also dislikes people going off on tangents or expressing views that are not backed by sound analysis and data. In this team setting, people will be hesitant to bring up concerns that are not fully formed or supported by data and analysis. This leader's strength in keeping a meeting on track can also become a weakness if it results in people being less forthcoming in expressing their views. She needs to be aware of the impact of her style and take actions to ensure that a range of views are surfaced and debated. She may want to allocate more time for team discussion on particular topics or use specific in-meeting techniques to surface views (such as asking each person in turn to “weigh in” on the topic being debated). She may also follow up with individuals after a team meeting to more fully discuss any concerns they may have.

The challenge is to remain focused on the decision that needs to be made while simultaneously paying attention to subtleties that can easily be lost in the heat of debate.

The central point is that leaders need to understand the traits and tendencies of those with the power to impact their success. Take the case of Steve MacMillan. He was the CEO of Stryker, a major Michigan-based supplier of medical devices. MacMillan had been hired at age forty-one to take the firm, which was very successful, to the next stage of its growth.3 In seven years, he tripled the firm's revenues and moved deftly during a downturn in his industry. MacMillan was also increasingly visible in the national media as an influential spokesperson for the business community and was seen as a possible CEO candidate for even larger firms, such as Johnson & Johnson. His personal life, however, was in turmoil. MacMillan had gone to several of his board members and told them he was getting a divorce from his wife, whom many of the board members knew well, and wanted to date a woman who worked as a stewardess on the company's corporate jet. In essence, he wanted their approval for a relationship that he knew could be problematic. Soon thereafter, MacMillan was pushed out of the company, allegedly because board members were troubled by what they saw as his handling of the situation. In particular, some members of the board believed MacMillan was less than candid with them in indicating when his new relationship actually began (they felt it had started far earlier than he had indicated). In reflecting back on this period, MacMillan noted, “Managing a board was not my strength at Stryker. It hurt me.”4 What is remarkable about his downfall is that a very smart individual failed to anticipate how a group that was critical to his success, a group that he knew well from his years as CEO, would react to his behavior. How could he not see that his actions would damage his credibility and, as it turns out, his career?

PAY ATTENTION TO BEHAVIORAL FLAGS

Beyond an awareness of each individual in the decision-making process, the leader needs to be aware of subtle cues that surface in a variety of settings. Here are the types of warning signals to watch for and possibly investigate further:

- Nonverbal behaviors. Leaders need to watch the nonverbal behavior of team members carefully, particularly when a team is engaged in heated conflict. This can be as subtle as someone rolling his eyes or team members who will not look directly at each other when making their points. Other considerations include the level of interest or engagement or openness that people signal through their behavior, particularly in meetings. The leader doesn't necessarily need to respond to nonverbal behaviors during a meeting but should make note of those that suggest issues that need to be explored.

- Silence. In leadership teams, members who don't support a decision often simply disengage from the group discussion and remain silent rather than pose a contrary point of view—particularly if the leader appears to support the decision or the group is moving quickly to closure. The senior leader should constantly monitor who is contributing to a group discussion and who has mentally checked out. Often these people will voice their concerns only outside of meetings, to their peers or members of their own teams.

- Nonanswers. People can opt out by appearing to agree with the leader when, in fact, they do not. A sign that this may be occurring is that individuals will not answer a direct question and instead will take the discussion into another direction or provide evasive answers. I have found that people will also use deflecting statements such as, “If you think it's the right decision, that's good enough for me,” or, “This is not my area of responsibility and I defer to the experts.” They become adept at avoiding the issue on the table and being forced to voice a point of view that they would rather keep to themselves. When I asked one leader about his being less clear than needed on his commitments to those above him, he said, with a touch of sarcasm, “I have spent years developing an ability to be less than direct, particularly in regard to my annual objectives. It is one of my more valuable skills.”

- Omissions. It is often what is not said during the discussion of an issue that is most critical—particularly on decisions that the leader believes will be problematic. I worked with a team that was aggressively pursuing an acquisition and, in the process, no one mentioned the potential culture clash between the two firms (even though their ways of conducting business were very different). People were not being deceptive in failing to recognize what would be a major issue if the deal went through; they simply assumed that the culture of the acquiring company would become the dominant way of operating. This assumption became evident when the leader noted the lack of discussion on this topic, which he viewed as a concern in integrating the two firms.

- Specific language. People surface their true feelings in hundreds of subtle ways. The leader needs to pay particular attention to the use of specific words that are red flags, suggesting that more discussion or follow-up is needed. A team member might comment that a proposed initiative is a “massive” risk or that a proposed practice is a “violation” of the firm's long-standing principles. Team members may also have specific phrases that they use to signal concerns. For instance, a team member may indicate that the team was “getting in front of its headlights” when he was concerned that they were moving too fast to make a well-informed decision. When the senior leader heard this phrase from this team member, whose judgment he trusted, he realized that he needed to dig deeper and determine the nature of the risk he was facing.

- Shifting positions. In many groups, team members will support each other in predictable ways or, conversely, take contrary points of view on particular issues. The chief financial officer of a firm, in many cases, will challenge the commercial line leaders on managing expenses. These differences can result in coalitions within a team that are generally present (certain individuals will often support each other on a range of issues) but also occur in relation to specific issues. Certain individuals may be more likely to support growth through acquisition investments than others who typically take a more guarded or even cynical view of proposed deals. A leader wants to pay particular attention when these coalitions are different from what he or she would expect, as that difference often signals a need to get to a deeper level of understanding on a particular issue. A team member who wants to move forward quickly with a proposed deal even though he or she typically advocates a go-slow approach is seeing or responding to something unique that the leader will want to understand. The same can be true when coalitions form in the decision process between people who are generally not inclined to support each other (or, inversely, who are opposed to each other when they usually are mutually supportive).

- Off-line input. Often, what people bring to a leader (or each other) during breaks from meetings or in informal hallway conversations is more important than what is said in formal discussions. While not all of these conversations are significant, they often provide the leader with a sense of what people really believe about a topic or the best course of action. Savvy leaders pay attention to these informal conversations and their potential significance for illuminating blindspots the leaders may have regarding a decision or area of the business.

- E-mail traffic. In many firms, e-mails offer insight into potential issues that may require a leader's attention. Sending an overly formal e-mail, with multiple people copied (or blind copied), is often a protective action taken by a team member with concerns or one who doesn't trust some other members of the team. Another sign of trouble is an e-mail from a team member on a complex and perhaps sensitive problem, one that clearly requires face-to-face interaction. Specific e-mail norms are unique to each firm's culture, and therefore what constitutes a warning flag in one company may not require much attention in another. A savvy leader is aware of his or her organization's culture and pays attention to behaviors that violate accepted norms, seeing them as warning signs that require follow-up.

Each of the above signals requires that the senior leader answer two questions: (1) Is the potential issue one that warrants further analysis or discussion (or is it “noise” that should be ignored), and (2) if the issue is significant, what is the best way to obtain necessary data and input? There is no set of guidelines to answer these questions, and a leader must often use his or her intuition to determine what is important and what is noise.

These signals can come from a variety of stakeholders who influence a leader's success. In most cases, the flags come from within the company and indicate a need for additional data. They can also come from other sources, such as boards. David Neeleman, founder of JetBlue Airways, was removed from the CEO role by his board after he mismanaged problems arising from a severe ice storm. He hadn't recognized that his board members had only a limited understanding of the company because they met only once a quarter for four hours. There were subtle signs that they needed to be engaged more fully and better understand how the business operated. Neeleman now believes that he should have taken more time to update his board, because others filled in the gaps in a manner that was not to his benefit.5

CREATE OPENINGS FOR CONTRARIANS

Most corporations need formal or informal mechanisms to encourage views that are different from the dominant culture or prevailing point of view on any given issue (including the leader's own thinking). A leader needs to encourage these viewpoints, particularly in regard to the vetting of a full range of views on key decisions or areas of the business. Eric Schmidt, former CEO of Google, describes his process as follows: “If you don't have dissent, then you have a king…. What I try to do in meetings is to find people who have not spoken, who often are the ones who are afraid to speak out, but have a dissenting opinion. I get them to say what they really think and that promotes discussion, and the right things happen.”6

Each organization's culture will dictate the approaches that are most effective—consider the following for your own team:

- Leaders can use team roundtable discussions to surface concerns. An issue is identified by the leader: “How are people feeling about the proposed acquisition? What are the risks we face if we go ahead with the deal?” This can result in a general discussion, with active give and take among the members. Another approach has each team member, in turn, expressing his or her view without others commenting, arguing a contrary point of view, or engaging in problem solving. After each member has commented, the leader directs the conversation to specific topics or individuals for discussion and debate. The key is to ask the right questions and probe for more detail with each follow-up question, such as, “What are your concerns regarding the target company. Why do you think our cultures are a poor match?”

- One of the best approaches for surfacing divergent views in leadership is simply to allow silence to enter the conversation, either when meeting one-on-one with people or in group meetings. Most leaders believe they need to move issues forward as quickly as possible, and so they do not allow difficult topics to simply remain on the table. However, people will usually tell you what is on their minds if you don't jump in first in order to fill in what can feel like an awkward period of silence. Ask people simply and directly what they think—and then give them time to fill the silence.

- Leaders often need to follow up team meetings with one-on-one discussions with particular individuals. As obvious as this appears, many leaders fail to do it after leadership team meetings. They believe that people stated their views in the meeting and follow-up discussions are unnecessary and even a waste of time. In most cases, however, people are more open when meeting privately with the senior leader than they are in a group meeting. It is particularly helpful when the senior leader makes an effort to go to their offices, often informally, to solicit input and any additional thoughts on the meeting or, more specifically, any controversial topics. This approach does not mean that candid discussions take place only outside of meetings; however, it does recognize that follow-ups are sometimes needed.

- In every organization, there are people who engender trust, and others will reveal information to them that they may not share with the leader or in a group meeting. These individuals are information hubs; they are the ones who have the best understanding of how members of a team or group truly feel about a decision or potential risk. The leader needs to understand the important role these people play in an organization or team and how to tap into them to understand what issues require further exploration. This can be as simple as an informal one-on-one discussion where the leader solicits input on how people in general are feeling about a decision or the leader's preferred course of action.

People quickly form an opinion of the degree to which a leader truly wants to hear contrary points of view and is willing to be influenced by others. I know of one team where a new leader stated that she wanted her people to challenge her when needed to ensure high-quality decisions. However, when one of the more forceful members of the team did so, he was closed down by the leader, who controlled the discussion and advanced her own preferences. After several interactions of this type, most team members became passive in meetings and were unwilling to challenge the leader, even when they believed it would be in the best interests of the organization.

Leaders also need to reach out to others and surface concerns that may not be obvious. I worked with a leader of a sales and marketing organization who went to her CEO with a proposal to change the way the firm's customer groups were segmented (which would result in revisions to a variety of marketing and sales practices, including compensation). The CEO liked the idea and told the leader to bring the proposal to his next leadership team meeting. She presented the idea and was surprised that some members of the team resisted her idea (which in her mind was based on sound analysis). The team discussion ended with the CEO indicating that more time was needed to review the proposal and determine whether the company should make the suggested changes. Frustrated, the sales leader met with the CEO after the meeting and asked why he didn't green-light the proposal. She was confused because he had indicated his support for it in their private conversation before the meeting. He said to her:

You needed to get a better feel for where people stood before you pushed for this change. You didn't get any input before the meeting from your peers, who need to support the proposal if we move forward with it. Then you were surprised when they raised concerns and acted defensively. I expected that you would review the proposal with the key people and see where they stood prior to your presentation. Why should I push forward with this when you didn't do what was needed?

ESTABLISH A THREE-STRIKE RULE

Mark Ronald, former CEO of BAE Systems, Inc., used an approach that he called the three-strike rule to encourage those with concerns about a particular decision to be tenacious in advancing their recommendations.7 Not every business issue needs to be resolved immediately, and granting more time often serves to clarify positions and bring fresh viewpoints or data to the discussion. In this regard, the leader is moving beyond reading subtle signals to increasing the strength of those signals. This approach suggests that the senior leader needs to underscore the responsibility of all organizational members to surface issues or concerns that may threaten the success of the enterprise (even when it is difficult to do so and may involve some personal risk).

The leader emphasizes that any area of concern that affects the larger enterprise should be given three opportunities for a hearing by the leader and his or her team. It may be accepted for further action at any time, but if it is rejected three times, it will not be debated again. With this approach, the leader is saying that he is not the final line of defense in determining what needs attention for the organization to be successful. Each time the same issue is surfaced, the individual advocating the position has a responsibility either to present new data or analysis that has not been heard before—or to cultivate further support from others who were not present or supportive in earlier discussions. This requirement prevents people from making the same argument that was ineffectual in earlier discussions (and thus engaging the leader or group in an unproductive repeat of earlier debates).

The three-strike rule came into play when a midlevel manager brought a proposed acquisition target to the attention of the senior leadership, with the recommendation that the deal be made. However, the CEO said he was not interested in the technology of the target company and did not see a significant growth opportunity in the firm's product area (strike one). The midlevel manager did not give up on his idea. He collected more data on the upside revenue potential of the deal and learned more about the potential application of the target firm's technology in new growth areas. The idea was presented again, but the CEO still did not favor the proposal (strike two, despite bringing new data to the decision process). The midlevel manager then went to the chief finance officer and chief technology officer to review the potential he saw and to solicit their support. He argued that the business environment was changing and, as a result, the earlier negative view of the proposal was wrong. They agreed that the idea had merit, and the three of them then went back to the CEO, as an informal coalition, to advance the deal. The CEO, seeing the level of support from the CFO and CTO, whom he respected a great deal, reconsidered and allowed the next-level analysis to move forward (no strike three). The deal was eventually completed and has been extremely successful for the firm. The midlevel manager deserves credit for being tenacious in pursuing an idea that others, including the CEO, did not initially support. In addition, the CEO deserves credit for being willing to review the proposal several times, with the caveat that new data or new points of view are brought into the discussion with each successive discussion.

Another feature of the three-strike rule is that it recognizes that dissenting members need to join the majority after three failed attempts to change the others' minds, and they must support the decision made by the senior leader or his or her team. In cases where this norm does not exist, teams can come to believe in what can be described as the right of infinite appeal, which allows them to constantly come back to a decision that was made in the past and seek to overturn it. This results in a waste of team time and, in many cases, an unwillingness to fully execute a decision (as some members think that the decision may eventually be overturned).

LISTEN DIFFERENTLY

Carlos Ghosn, CEO of Renault and Nissan, believes the best leaders have confidence and resolve, particularly when pressing forward with changes in how an organization operates. He also believes leaders need to be open and empathetic to others, taking into account their points of view. He suggests that leaders listen openly before a decision is made and then become drivers of results once it is reached. He observes that these two requirements are rarely found in the same person. That is, some leaders are too forceful and don't listen to others—particularly when their team is underperforming. Others are too open and don't use the power of their position to push people to execute at a higher level.8

Many leaders have a healthy degree of ego and are invested in being viewed as being decisive. In addition, they often assume they are listening to others when in fact they are missing or misinterpreting the key points that others are making or want to make (if only given more time to do so). Many leaders are superb analytical thinkers and are action oriented. They have limited patience with people who belabor the obvious or take too long to get to the core of an issue. They cut people off and finish their sentences. Some, however, learn that this approach has inherent risks as they move up in an organization and tackle more complicated problems. Amgen CEO Kevin Sharer says:

The best advice I ever heard about listening—advice that significantly changed my own approach—came from Sam Palmisano, when he was talking to our leadership team. Someone asked him why his experience working in Japan was so important to his leadership development, and he said, “Because I learned to listen.” And I thought, “That's pretty amazing.” He also said, “I learned to listen by having only one objective: comprehension. I was only trying to understand what the person was trying to convey to me. I wasn't listening to critique or object or convince.”9

This approach to listening is more in the spirit of investigation and diagnosis than problem analysis and resolution. You want to ensure, in situations that demand it, that you understand the point of view of others before pushing forward with solutions. In some cases, you also may have a sense of the issue, but you need to be careful not to look simply for input that confirms your assumptions. These data-gathering sessions require that you hide your biases and work simply to get the answer you want.10 At the same time, you need to be tenacious and come back to asking the same questions again if people are providing evasive responses. It can also help to repeat back to individuals, in your own words, what you are hearing from them, to ensure that your understanding is accurate. You might say, “I hear you saying that we don't have the systems we need to give you the data you need to run your business. Is this correct?” By doing this you will determine if you are on the mark and will also obtain more detail as the person with whom you are speaking responds to your question.

Leaders need to listen openly before a decision is made and then become drivers of results once it is reached.

Some leaders conduct dialogue sessions with their own teams as a way to surface divergent points of view. Often conducted over senior team dinners, sometimes with the help of wine, these informal discussions focus on broad strategic and operational topics. A leadership team might discuss how the culture of the firm is evolving as the firm grows and expands. Or the group might discuss what is occurring in the marketplace in regard to new competitors. I have also seen teams talk about more personal topics, such as managing and balancing the demands of both work and home. The senior leader should participate in these discussions but as a team member or even as a facilitator of the discussion, asking probing questions and getting people engaged. The goal is to surface different points of view and, unlike many corporate meetings, these sessions are not intended to come up with solutions or action items. The key to making them effective is picking the right topic and then setting the right tone to surface members' points of view. Some teams will also invite a few individuals from the next level of management to team dinners, assuming that the topics selected for discussion are not confidential or sensitive in any way.11

Listening well is not an easy task given the range of issues that a leader in a large corporation faces on a daily basis. Leaders are inundated with issues, many of which appear to be not especially important and yet harbor the potential to metastasize into something serious. The Columbia shuttle disaster is a case in point in that the project manager who ignored the signs that the spacecraft was damaged on launch was also dealing with hundreds of other in-flight issues that demanded her attention. Effective leaders develop formal and informal practices that make weak signals more visible and assess those signals to determine the level of risk involved. In one of the most honest assessments of failure on this front, Wayne Hale of NASA, a senior flight director for forty shuttle missions, reflected on his role in the Columbia shuttle tragedy:

I had the opportunity and the information and I failed to make use of it. I don't know what an inquest or a court of law would say, but I stand condemned in the court of my own conscience to be guilty of not preventing the Columbia disaster. We could discuss the particulars: inattention, incompetence, distraction, lack of conviction, lack of understanding, a lack of backbone, laziness. The bottom line is that I failed to understand what I was being told; I failed to stand up and be counted. Therefore look no further; I am guilty of allowing Columbia to crash.12

ACTIONS FOR DEVELOPING PERIPHERAL VISION

The following worksheet will help enhance your ability to recognize “weak signals” that are pointing to potential blindspots that require your attention.

DEVELOPING PERIPHERAL VISION: SUMMARY OF ACTIONS MOVING FORWARD

This chapter is based on an article I coauthored with Mark H. Ronald, “Developing Peripheral Vision,” Leader to Leader 48 (Spring 2008).