CHAPTER

6

SEEK OUT THAT WHICH DISCONFIRMS WHAT YOU BELIEVE

One of the more robust findings in the research on decision making is that people tend to see what they want to see and they interpret new information within the context of their existing beliefs. This makes seeing something different from what they already know, or want to occur, very difficult.1 A leader who paid the price for falling into this trap was Robert McNamara. In the 1950s and 1960s, he was one of the most visible and powerful leaders in the United States—first in business, as an executive and eventually president of the Ford Motor Company, and then in government, as the secretary of defense for two American presidents. Supporters and critics alike viewed McNamara as a brilliant man with unmatched analytical skills. He took on big challenges and methodologically developed his plan of action. President John Kennedy described him as the smartest individual he ever met. Lyndon Johnson observed, with a mixture of admiration and concern, “He's like a jackhammer. No human being can take what he takes. He drives too hard. He is too perfect.”2

With time, McNamara has come to personify the limits of raw intelligence and quantitative analysis—as he believed that numbers, properly understood, would provide him with what was needed to win in both business and war.3 He was smart and arrogant—a combination that resulted in a general unwillingness to deviate from what he believed was needed in any given situation. He used his analytical skills to intimidate others and push forward with his plan. At Ford, this meant continuing to cut costs even after his company had recovered from near-bankruptcy. His obsessive focus on financial metrics resulted in Ford's producing cars that were increasingly less appealing to an increasingly affluent public. Those in Ford who loved cars felt that McNamara was a numbers guy who helped save Ford in the short term but would kill it in the long term. In government, he demonstrated a similar weakness in being rigidly focused on proving his view of reality. He was unable to understand the broader political and social world in which he was operating.4 Once committed, he blocked out facts and points of view that were at odds with his plan of action. Instead, he focused on metrics that fit his beliefs regarding what was needed to produce success. He became “tunnel blind” in what he saw and, even more troubling, unwilling to admit when he was wrong. His intelligence and tenacity allowed him to defend his approach, at least to himself, even when events and people turned against him. One of the most data-driven of leaders couldn't see what was in front of him—couldn't see what was obvious to those who were far less talented and accomplished than himself.

McNamara was extreme in both his strengths and blindspots—but certainly not unique. Many leaders, particularly those who are successful, have difficulty looking objectively at themselves and their environment. The author Kathryn Schulz, in her examination of why people have difficulty realizing when they are wrong, observes: “A whole lot of us go through life assuming that we are basically right, basically all the time, about basically everything; about our political and intellectual convictions, our religious and moral beliefs, our assessment of other people, our memories, our grasp of facts. As absurd as it sounds when you stop to think about it, our steady state seems to be one of unconsciously assuming that we are very close to omniscient.”5

ASKING THE RIGHT QUESTIONS IN THE RIGHT WAY

One of the highest compliments new leaders can receive from others in their firms … is that they are “asking the right questions.”

This chapter focuses on approaches for surfacing disconfirming data—which I define as information that challenges the basic assumptions and beliefs of a leader. One of the keys to surfacing such data is asking the right questions. Many leaders view their role as providing the right answers, but asking the right questions is often a more important, and a more difficult, undertaking. This is particularly true among leaders who are self-confident and have a bias for action. They trust their own judgment and can grow impatient with those who, to the leader's mind, overanalyze situations. The goal is to get these types of leaders to slow down and to have them ask the questions that will give them the data they need to better assess their opportunities and risks. Jim Collins, author of a number of well-respected management books, describes this outcome as getting the “questions to statements ratio” right—learning, in other words, to ask more questions and make fewer pronouncements.6

I often work with new leaders who are transitioning into higher-level executive roles. One of the highest compliments they can receive from others during this process is that they are “asking the right questions” as they move into their new roles. This is a shorthand way of saying that they are not coming in with the answers but are being savvy and insightful in gaining an understanding of the critical issues that need to be examined. Asking the right questions also means that a leader is working to acquire deeper insights into what is occurring—peeling back the onion to get at the vital few issues and opportunities facing a group or company. The need to do this applies to more tenured leaders as well. In the case of JP Morgan Chase, noted earlier, this would mean that rather than trusting that his staff was in control of potential risks, Jamie Dimon would have asked next-level questions about the London Whale trades. There is no set of rules on when and how to ask the questions that will surface disconfirming data. The guiding principal, however, is that leadership, when done is the ability to ask the right question in the right way. Some general guidelines are helpful to a leader who wants to better understand his or her vulnerabilities:7

- Avoid yes-or-no questions. Questions are called closed-ended when they can be answered with a yes or a no. In the London Whale case, a closed-ended question would have been, “Do we have a problem with the London trades that I need to worry about?” These types of questions are efficient but don't surface data that may be critical to a leader's understanding. Questions are called open-ended when they allow for a variety of responses and provoke a richer discussion. In the London Whale case, an open-ended question would have been, “How are the trades structured, and why did you structure them this way?” The open-ended question broadens the discussion and allows the leader to surface a richer set of data on which to make decisions.

- Don't lead the witness. Hard-charging leaders often push to confirm their own assumptions about what is occurring in a given situation and what is needed moving forward. This can result in questions that are really disguised statements. To some extent, this occurred in the Columbia disaster, as the manager led her team through a set of questions that confirmed her belief that she didn't have a “mission critical” disaster on her hands. She needed to be more open to hearing divergent points of view and, in particular, seek out those views. The nuance in the process is to probe for understanding by being directive but not to the point of closing down contrary points of view. That is, your questions should not be simply open-ended but should take the person answering the questions down a path that provides more insight. This is not to say that all views are equal or that every option can be explored. The Columbia program manager faced hundreds of potential problems, with the foam strike being but one of the issues she and her team needed to monitor. That said, leaders with strong personalities who drive for results need to be careful that they don't unintentionally prevent contrary points of view from surfacing.

- Beware of evasive answers. In some situations, people will avoid giving direct answers to direct questions. They may not know the answers or not want to provide the answers (for a variety of reasons, including a desire to appear smart or the potential for an outcome different from what they want if they reveal particular data). People at a company, for instance, will in some cases want to internally “sell” an acquisition even though it carries clear risks. They will minimize these risks or unknowns while maximizing the upside potential of the deal—as part of convincing key decision makers to move forward. Leaders need to come back to any question on the table that is being avoided and ask it again until they get a straightforward answer. The answer may be, “We don't know,” but that is better than an evasive or misleading response.

- Ask for supporting data or examples. Leaders want to ask questions that surface points of view and, at the appropriate time, also clarify which answers are based on fact and which are based on speculation. They should encourage people to say what they know and what they think they know, and make sure they clarify the difference. Leaders should also ask for data, and even examples, when people state their views about what is occurring in a given situation. Some leaders, however, take this need to an extreme level and close down a healthy debate if the emerging facts do not support a particular point of view. In the case of the Columbia disaster, the engineers with concerns had some evidence that the foam strike was severe (photographs taken during launch) but could not prove that the shuttle was in danger. In fact, they wanted to collect more data to inform the analysis of the potential problem—a request that was denied.

- Paraphrase to surface next-level details. One technique to productively push people to provide more information is to paraphrase what you are hearing. You might say, “Let me make sure I understand this correctly. You say that the trades pose a risk only if the economy in Europe declines at a rate beyond what our experts are telling us is possible.” While this may result in a yes or no response, proceeding to next-level questions can open up the dialogue. Some leaders even exaggerate or misparaphrase what they are hearing in order to provoke a richer dialogue. The leader might say, “Some people hearing what you have just said would think that you are suggesting that we will never see a decline of 5 percent in the GDP of Europe. Is that what you are saying?”

- Ask for alternatives. Another approach to surfacing disconfirming data is to ask for the opposing point of view. This request can be along the lines of “I like your plan. But tell me about the weaknesses in your approach. What would your critics argue?” A related line of questioning is to ask the respondent to alter his or her fundamental assumptions about the future: “You are assuming that India will grow at 10 percent a year for the next five years. What happens to your plan if it grows at only 5 percent?” Or the leader might question an assumption that an upside opportunity exists: “You are asking for $10 million to grow this brand. What would you do if we gave you $25 million? What could you deliver with that level of investment?”

- Give an opening for additional input. Leaders will also want to provide an opportunity for others to offer additional input and, in particular, dissenting views. Often, the final moments of discussions are rich in that people will sometimes choose that time to surface what is important to them—either coming back to something they mentioned earlier in the discussion or surfacing new information. A leader can encourage this by asking for any additional input at the close of the discussion. John McLaughlin, a former leader with the Central Intelligence Agency, would sometimes end his conversations with others by asking, “Is there anything left that you haven't told me … because I don't want you to leave this room and go down the hall to your buddy's office and tell him that I just didn't get it.”8

In seeking information that challenges your existing views, you will want to focus on the following areas:

- Your leadership impact

- Your team's strengths and weaknesses

- Your organization's strengths and weaknesses

- The markets and industry in which you compete

SURFACE DISCONFIRMING DATA ABOUT YOUR LEADERSHIP IMPACT

Most of us look for information and points of view that confirm what we already believe or want to happen. In doing so, we exhibit what is called confirmation bias. As noted in Chapter Four, this occurs when information that confirms what we think is true is recognized, while information that challenges our beliefs is ignored or discounted. My intent here is to provide advice on how to productively challenge what you believe in order to avoid blindspots and their potentially negative consequences. You can surface disconfirming data with the following techniques:

- Become your own devil's advocate.

- Track your decisions over time.

- Conduct in-depth 360 assessments.

- Extract leadership lessons learned.

Become Your Own Devil's Advocate

One well-known approach to surfacing disconfirming data is to assign one person in a group or firm to be the devil's advocate in relation to a specific decision that needs to be made. This role is based on the historical practice in the Catholic church of selecting an individual to argue against, to be the primary dissenter, regarding the canonization of the person being considered for sainthood. The advocate's role was to refute claims that the individual had performed saintly actions and, more generally, suggest why he or she was undeserving of being viewed as a saint. This was done for every candidate to prevent unworthy individuals from being elevated to that status. In a corporate setting, the devil's advocate technique can be used to counter groupthink tendencies in a variety of areas. A person in a leadership team may be asked to develop the case against a potential acquisition that many members of the team favor. The intent is to surface potential downsides of a particular deal so as not to be swept up in “deal fever.” The technique can also be used more informally by asking, for any given decision, what those who oppose the majority view think. These are the dissenters whose voices need to be heard in the decision-making process.

The technique of using a devil's advocate is well known but vulnerable to several pitfalls. The first occurs when the advocate must operate within a set of informally stated norms that dictate what type of opposition is acceptable. The advocate may be within bounds in questioning how a strategy is implemented but out of bounds if he or she questions the viability of the strategy in total. In such cases, the merits of having a devil's advocate are limited. A second and related trap is for a group to believe it has truly debated opposing views when, in fact, its members never took these opposing arguments seriously. The counter argument is never truly engaged and is put on the table merely for the sake of appearances. The group then moves forward with an erroneous belief that the risks have been fully explored.

A variation on this technique is for a leader to become his or her own devil's advocate. In this case, the leader deliberately develops the strongest possible arguments against the course of action that he or she is favoring. The leader starts by clarifying the opposing views, even what his or her worst critic would say about the proposed decision. Then the leader deliberately seeks to develop the business case against his or her plan (which may still be in the formative stages). Legend has it that the great scientist Charles Darwin would pay close attention when an observation or fact contradicted a belief that he held. He made a habit of writing down contrary points of view within thirty minutes of coming to his attention, before his mind could find reasons to reject the information.9

■ ■

The outcome of exploring views that conflict with your own current thinking is a more rigorous approach to making decisions. The end result may be that you decide not to move forward with a plan because the downsides or risks are too great. Or you may move forward with the plan but with a deeper appreciation of the potential vulnerabilities in doing so, and a clearer view of the actions necessary to avoid those pitfalls. This requires that you resist, initially, the tendency to move rapidly into an advocate role for a particular course of action. Instead, you need to keep your options open and review the pros and cons of a decision in the true spirit of inquiry.10

Track Your Decisions over Time

Charles Darwin made a habit of writing down contrary points of view within thirty minutes of coming to his attention, before his mind could find reasons to reject the information.

Imagine that you take a vacation and bring along a number of business periodicals, some now several years old, that you had not found time to read when they were first issued. As you read the older articles, you see how wrong some of the authors were regarding the economy, the stock market, and the fate of individual firms. Some, for instance, incorrectly predicted that certain companies would thrive and be solid financial investments. Twelve months later, these predicted “winners” have stumbled and are now worth less than half of their value when recommended by the pundits. You also realize in your vacation reading that few people, including experts, take the time to go back and assess the accuracy of their predictions.

A technique that a leader can use to better assess his or her decision-making ability is one that Peter Drucker suggested years ago.11 He thought that leaders could learn a great deal by writing down the reasons behind their key decisions, including their expectations of what would occur. Then, after a period of time, they should review the accuracy of their expectations and the lessons learned. This approach can be used on a range of issues from strategic investments (“Did the acquisition we made a year ago turn out as I expected?”) to personnel decisions (“Did the R&D leader I hired turn out to be as strong as I thought?”). In most cases, there are lessons to be learned even when things turn out well, as they most likely evolved in a manner somewhat different than expected. This practice is also a way to avoid the tendency of most people to minimize or explain away bad decisions. The cliché that “failure is an orphan” has an element of truth to it, as many leaders quickly distance themselves from decisions that turn out poorly. I recall a leader who introduced a new product that was designed to generate revenue beyond his firm's current product portfolio. Instead, the new product cannibalized the firm's existing product line and didn't contribute to overall top-line growth, despite a huge investment including a highly visible marketing campaign. The leader behind the initiative quickly developed a story line that placed blame on others for the failure of the product and worked hard to erase his fingerprints from the effort. Drucker's technique, in contrast, helps you to identify and learn from your mistakes and, in addition, will confirm your insights and judgment when your decisions and predictions are proven to be correct.12

Conduct In-Depth 360 Assessments

One of my clients believes in the necessity of conducting a full assessment of her leadership capabilities every two or three years. She does this because she has seen too many leaders develop blindspots as they rise into higher-level roles, hurting not only themselves but their companies. They become increasingly isolated and fail to see their own weaknesses or the threats they face. It is natural that some leaders, as they become more powerful, surround themselves with individuals who operate in a highly political manner; although skillful, they put their personal interests before what is best for a company. A senior leader may not see the negative impact these people are having within the company and the damage done to the leader in trusting such individuals. A 360-degree assessment or survey (a “360”) is one tool that can bring such issues to the senior leader's attention. The power of a 360 to surface blindspots depends on the leader's openness to feedback and also on the skill of the person conducting the 360. There are a number of common mistakes. First, some 360s collect feedback via a survey that is sent to people (instead of via face-to-face interviews). While interviewing is more time consuming, the data from a 360 are much more valuable when a skilled interviewer collects them in person. An interviewer can probe in more depth and can collect specific examples of behavior that the leader will want to examine. The examples are helpful in giving the leader insight into others' perceptions of his or her leadership style and impact. An interviewer can also ask for specific recommendations on what the leader needs to do to address a blindspot or to develop a specific capability.

Second, some leaders, after reading their 360 report that identifies possible areas for change, focus on improving those areas that are peripheral to their success. I have seen 360s in which input from a significant number of people indicates that the leader needs to develop his or her strategic skills. The leader, after reading the report, glosses over this point and, instead, wants to focus on further improving his operational skills (which, like most skills, could still be improved but which are already very good). In so doing, he is misreading what is required to be successful as a senior business leader. He focuses on the areas that may be easier to develop but less important. Leaders can also overreact to some comments and believe they need to change in areas that are relatively unimportant. For instance, results from a 360 may suggest that a leader be less forceful in pushing for change (as people find this style abrasive). The problem here, however, is not the leader but the culture of the company, which is resisting necessary change. The leader may want to refine his or her approach but should not back off from being a change agent. A third mistake occurs when a leader identifies the right areas for development but doesn't take the actions needed to truly change in an area of identified weakness. This is the leader who needs to improve her presentation skills and decides to take a course on communication skills and thinks that will be sufficient. Instead, she should commit, at the minimum, to make at least one speech a month and obtain ongoing feedback from others on the quality of her speeches. In many cases, the actions identified after a 360 report are underwhelming—in that they lack the impact needed to truly develop the leader in the targeted areas. Instead, the leader opts for a plan that is easier to implement and less painful, but do not truly challenge the leader to learn new skills.

A final mistake is that many 360s have no formal follow-up process to assess a leader's progress in the targeted areas.13 The leader uses the 360 report to identify the right areas and puts into place rigorous plans for improvement. However, either the leader doesn't follow through on the improvement efforts or he or she makes some initial progress and then reverts to past form. The lack of follow-up is true in many cases both for the leader and for his or her supervisor, who fails to assess the progress of the individual and provide ongoing feedback and advice.

Useful information can be gleaned from looking at comparisons between yourself and other leaders. This is evident when a new leader comes into a role and is compared by others to the leader whom he or she has replaced. People contrast the two and form judgments about the new leader based on those comparisons—fairly or not. I find that respondents to 360 surveys provide more useful feedback if asked, in a skillful manner, to make explicit comparisons. This can be achieved in one of several ways. First, the leader can ask others how he or she compares to other leaders. One of my clients would periodically ask a trusted direct report if his behavior was similar in specific areas to what he had observed in other leaders. He found it distasteful, for instance, when another leader made decisions that benefited those who were loyal to the leader and was less concerned with what the business needed (resulting in unearned promotions and project assignments, for example). He also realized that if he was not careful he too could actually fall into the same trap (“There, but for the grace of God, go I”). As a result, he would ask his trusted team member whether he saw any similar behavior on the leader's part and to provide specific examples if he did so. A second approach is to ask another person to collect this type of information on behalf of the leader. The individual conducting a 360 assessment can ask questions that surface information that is disconfirming. In the course of conducting a 360 assessment, I will ask those I am interviewing a range of questions on a leader's strengths and weaknesses, including the following comparison questions:

- How does this individual compare to the best leaders you have seen?

- Does his or her style remind you of other leaders in the company? If so, how so?

- How does he or she compare to the best leaders you have seen in regard to X (identifying one or two areas thought by the leader or interviewer to be critical to the leader's success, such as strategy development or ability to execute complex initiatives)?

The goal in these questions is not to rank the leader in comparison to others or suggest that others be mimicked but, instead, to surface concrete feedback that will benefit the leader in further developing his or her leadership style.

Leaders who don't want to conduct a formal 360 can collect feedback on their own. The key is to realize that the power of the leader's position will influence how direct people will be with him or her. Most people are less forthright and honest in expressing their concerns directly to those in a position of power for a host of reasons, including a fear of retribution. Leaders often underestimate how the position in which they sit distorts the feedback they get. A skillful leader, however, finds ways to make people comfortable and get them to open up. One technique is to periodically ask a few people, perhaps members of the leader's team, to identify the things that the leader is doing well and three things that he or she could improve. The leader should pay attention to both the positives and areas for improvement—asking for specific recommendations on how to further leverage the strengths and address the weaknesses. As with the 360 data, not all of what the leader hears will be on the mark, but the exercise can produce helpful insights into potential blindspots and areas for change.

Extract Leadership Lessons Learned

Another helpful technique for maximizing self-awareness is an annual self-assessment of lessons learned about one's own leadership effectiveness. Many firms ask leaders to assess their progress against a formal set of objectives. Less common is a focus on deeper insights regarding one's leadership over the course of a year, which can involve both successes and failures. I have worked with leaders who summarize these lessons in a two- to three-page year-end memo that outlines what they learned and, in some cases, what they need to improve on as leaders in the upcoming year. Those who engage in this exercise derive the most value out of forcing themselves to think deliberately and systematically about what they have learned. Most leaders have made at least a few bad hires over the course of a year and will benefit from examining mistakes in their hiring process (such as not choosing the appropriate recruiting firm, not using the best people as interviewers, or not fully checking references), or the leader may have used the wrong assessment criteria (such as not considering a new person's fit with the existing culture). A leader will want to take several weeks to reflect on his or her year-end lessons learned and identify specific examples in each area to make the assessment more meaningful. As mentioned, some leaders write a “lessons learned” memo. They may keep this document to themselves or share it with a supervisor or a trusted confidant, as background to an in-depth, one-on-one discussion regarding their leadership impact and, more specifically, areas for improvement.

In this process, you will want to take into account the views of your critics, who find fault with your thinking, plan of action, or behavior. Many leaders tune out their critics, either ignoring them completely or even disparaging their point of view. Steve Jobs was famous for personally attacking those who disagreed with him, particularly if he didn't need them to achieve what he wanted. To some extent this is not surprising, in that highly driven and competitive people believe in themselves and their firms far beyond what others have to say about them. Success, as noted in Chapter One, typically compounds the problem, especially if you have proven adversaries and naysayers wrong. Dealing with the feedback of critics is complicated because you need to determine when to listen and when to ignore what they have to say. There is no formula for making that call. Your critics may be right only 10 percent of the time, but that 10 percent may be in an area that is critical to your success. One approach is to entertain the possibility that your critics may be right and then attempt to justify their point of view in your own mind. A second approach is to ask someone you trust, someone with a reputation for being clearheaded and objective, if they see any merit to your critic's point of view.

SURFACE DISCONFIRMING DATA ABOUT YOUR TEAM

As with obtaining disconfirming data about your own leadership impact, you will benefit from obtaining a range of data about your team. As discussed in Chapter Two, some leaders have an inaccurate view of their teams or of particular team members. I find many leaders believe that their team is operating more effectively or team members are more aligned than is actually the case. Or the leader may view one or more members of the team with a halo effect; that is, once he or she has formed an opinion of certain people, the leader will not change that opinion, even in the face of conflicting data. This opinion can be overly positive or negative—in either case, the leader runs the risk of having a blindspot about these team members, which results in poor decisions on how best to deploy them. Several approaches for surfacing disconfirming data about your team are outlined in this section:

- Assess your team's effectiveness as a group.

- Conduct skip-level interviews with those in a level below your team's.

- Obtain in-depth assessments of individual team members.

- Create and monitor developmental tests for team members.

Assess Your Team's Effectiveness

The first approach to surfacing data is to periodically assess your team, on your own or with the help of internal or external staff. The goal is to determine what is working well in the team and what needs to change. The assessment of the group typically includes input from team members and, in many cases, from selected individuals working at the next level of management. These individuals interact with the team and have a point of view on how well it is operating. In most cases, the assessment includes open-ended questions regarding what the team should continue, stop, or start. Many of the assessments I have conducted over the years indicate that senior teams are spending their time in the wrong areas and need to focus on the few vital challenges and operate more strategically. Assessments can also survey the perceptions of those inter-viewed on the team's effectiveness. These surveys can be generic, assessing typical areas of team effectiveness such as the clarity of performance metrics. Or they can be customized to a particular team or organization. The survey might assess the extent to which the team is living the firm's values or the norms that the group adopted at an earlier point in time. The findings from the team are reviewed with the leader and then the team members, resulting in a few targeted areas for change moving forward. For instance, I worked with a team that found it was diving into operational details that were much less important than the larger strategic challenges facing its business group. The president of the group identified, with the team, four streams of activity essential to the group's future growth (such as e-commerce). Members were assigned to these strategic imperatives, along with high-potential leaders from the next level of the organization, and asked to develop a suggested strategy. This was then reviewed in some depth with the leadership team and modified as needed. The group also changed the nature of its monthly agenda and dedicated the majority of the team to reviewing strategic issues, including the four streams of activity.

Conduct Skip-Level Interviews

Some leaders collect disconfirming data about their teams by conducting periodic interviews with individuals one level below their team members in the organization. These meetings, called skip-level interviews by some firms, are one-on-one meetings with the leader and people from various groups and levels. One leader, for instance, talked with a more junior staff member and determined that a member of his team was acting toward the new member in a demeaning manner. This was a difficult discussion, as the more junior individual needed to trust the senior leader in sharing this information. The senior leader thanked her for her input, which was different from what he had seen of the individual (who managed up very well). The senior leader didn't act immediately on the information but kept it in mind as he looked for other sources of input on the leader in question. He learned that others had seen the same behavior but hadn't mentioned it to him because they believed he was aware of it and assumed that he didn't see it as a concern.

These skip-level interviews can also be more focused, asking for input on growth opportunities or the key operational areas that can be improved. Each leader needs to identify the right questions and send them to each individual prior to their meeting. Here are some examples of the types of questions a leader might ask in such meetings:

- What are the three greatest opportunities for growth over the next five years in our company?

- What is the greatest risk we face as a company over the next five years?

- Do we need to change the way we operate as a company to maximize our growth?

- From your viewpoint, how is my team operating?

- Strengths?

- Areas for improvement?

- What general advice do you have for me?

In some cases, people in these discussions also volunteer information about their direct supervisors (who report to the leader asking the questions). Most people, however, are reluctant to criticize their boss when talking with a more senior person, and the upward feedback regarding individuals is often positive. Nonetheless, a savvy leader will be able to read between the lines and obtain potentially useful information about how the team and particular team members are operating. The leader can also observe how people behave in these meetings. Are they passionate about their work and open in expressing their views? Are they proud to be part of the firm and committed to its success?

Obtain In-Depth Assessments of Team Members

Some leaders also surface necessary data about their team members with 360 assessments, often staggering the process so that several team members go through it each year. Data are collected on team members' strengths and weaknesses from the supervisor, peers, direct reports, and those in other groups. The leader of the group needs to receive a full copy of the report and recommendations, in order to increase his or her understanding of the team members. Some firms don't take this step because they believe the 360 data is owned by the individual and should be shared upward only if that person decides to do so. This results in minimizing the impact of the 360, as the supervisor, who should be coaching the individual, doesn't necessarily see the feedback data. The process I use is to meet first with the individual to review the report, focusing on both strengths and weaknesses. I then send a copy of the report to the supervisor, who reviews it and summarizes his or her key takeaways. The leader, direct report, and I sit down to review the key findings and implications. Finally, I work with the individual to create a twelve-month plan to address the areas of focus that he or she agrees are critical to his or her future success. I also believe it is helpful for the individual to review the findings of the 360 (in summary form) with the members of his or her team, asking for additional recommendations in the areas targeted for development.

One factor to keep in mind in reviewing 360 data is that the input varies in accuracy and usefulness. I conduct hundreds of interviews a year to assess leaders, and I am struck by the degree of variability in how insightful people are about others. In others words, some people are much better at leadership assessments than others. There are days when I will interview five people, asking each the same questions about the same leader, and I get very different levels of insight about that leader. In addition, in some cases the minority view of a leader is more on target than what the majority of people see in that leader. Thus a leader reading a report needs to understand that not all views are equal and that some of the input will be “noise” in the sense of being off target or less important. The caution is that the leader may also discount valuable input by seeing it in this light. A consultant's or advisor's interpretation of the feedback is helpful for understanding what needs to be addressed and what should be ignored in regard to suggested changes in a leader's thinking or behavior.

Create Developmental Tests for Team Members

Another useful technique to surface disconfirming data is to give team members assignments that stretch them and, in so doing, provide input on their capabilities. A leader might give a superb operational leader an assignment to develop a new strategy for the firm in an important area such as a new emerging market or product category. The team member needs to develop the strategy, often working with others, and review it with the leadership team. Or the leader may select a leader who has worked in one functional area of the business to lead the integration of a newly acquired company. This assignment requires the development of necessary knowledge of other functions in order to effectively manage the integration. In all cases, the leader should be clear about success metrics for the assignment (“our integration efforts must result in a cost savings of $100 million”) as well as specific developmental tests or opportunities (“you need to develop your ability to work across boundaries to develop the optimal design for the new organization”). These types of assignments provide the senior leader with useful data about a team member's capabilities in targeted areas and ability to work effectively when put into a challenging situation. An additional step is to interview three or four people who have observed the team member in his or her developmental assignment and ask for input. The senior leader can do this directly or ask an internal or external consultant to collect the data. The goal is to obtain rich data on how the individual performed, in particular on the stretch element of the assignment. The data from the interviews should be summarized and reviewed with the individual as part of his or her ongoing development.

SURFACE DISCONFIRMING DATA ABOUT YOUR ORGANIZATION

Leaders also need regular input on how their organizations are performing, beyond the obvious financial metrics. Several techniques are helpful in meeting this need:

- Rigorously review strategic performance metrics with your team.

- Solicit input from newcomers, outgoers, and outliers.

- Conduct deep dives in targeted areas of your business.

- Perform short-cycle reviews of progress.

Review Strategic Performance Metrics with Your Team

As noted earlier in the case of Robert McNamara, focusing on metrics is not without risks. However, metrics are a key tool in surfacing disconfirming data and what can be painful truths. Each leader needs a few carefully selected macro metrics that clarify to the leadership team and beyond what is important and how the performance of the organization will be measured. Metrics, when properly designed and used, make it difficult for the leader and his or her team to ignore weaknesses. A new leader who wants to promote ownership for the business can emphasize the importance of gross margin in his or her business reviews. If the firm has historically emphasized only top-line revenue, he or she can also modify the compensation system to reward performance on both the top and bottom lines. In many cases, leaders fail to develop a truly balanced approach and often look simply at financial metrics. This is not to minimize the importance of financial results, but it is also essential to have a broader set of metrics that are monitored and discussed over time. Once the metrics are established, the leader will want to review them on a regular basis with his or her team. The risk for many leaders, even if they develop the right metrics, is that they don't follow through and monitor progress in a disciplined or effective manner with their leadership teams.

In many cases, leaders fail to develop a truly balanced approach and often simply look at financial metrics—it is essential to have a broader set of metrics that are monitored and discussed over time.

One leader who is rigorous in using metrics is Alan Mulally, CEO of Ford. On coming into that firm from Boeing, he established the metrics by which the leadership team would run the business. He then set up a business plan review meeting where the metrics would be reviewed by his team every week.14 In some periods, given the challenges facing the company, he and his team met even more frequently. Mulally wanted to change Ford's culture by fostering more open discussion of performance, and in some cases difficult truths, in meetings—using an up-to-date stream of data as a tool that allowed his leaders to discuss what was truly occurring at the firm. However, he didn't want to use metrics as a weapon to punish people who were facing challenges—instead, the metrics were to help the team make informed decisions on how to improve business results.15 The merits of data-driven reviews, however, need to be balanced with the need for judgment beyond what data can offer. In some cultures, the reliance on data becomes so extreme that people will not come forward with concerns if the data they have are incomplete or inconclusive. Leaders also run the risk of having too many metrics as reams of data are collected and analyzed. As in most areas of organizational life, success lies in finding the right balance and not allowing decisions to be driven exclusively by data or, on the other extreme, entirely by intuition or opinion.

Solicit Input from Newcomers, Outgoers, and Outliers

Bringing new people into an organization can result in productive challenges to the status quo and make more visible weaknesses that need to be addressed. The challenge is to fully leverage the benefits that newcomers bring to a firm. One issue is that newcomers are sometimes intimidated by the success of the existing culture and don't feel they have the credibility or power to challenge it.16 Imagine that you joined Microsoft years ago, when the firm was dominating its technology rivals. Most likely, you would have noted some weaknesses in how the company was operating. For example, many have observed that Microsoft was not particularly adept at getting its people to work across internal boundaries to develop innovative products that would appeal to consumers. However, most people coming into the firm would be intimidated by Microsoft's history of success and not inclined to offer their observations regarding necessary changes. So as a newcomer you might have felt, with some justification, that you would be rejected by the dominant culture if you offered what others viewed as criticism from someone who doesn't understand how the firm operates. Most people want to become part of the team and will be less assertive in making their critical views known. In some cases, newcomers push their need to belong to an extreme and assimilate so thoroughly that they no longer see things from a different point of view.

In regard to the leadership team, a leader can set the tone that newcomers are valued and their perspective is valued. More specifically, he or she can reach out to newcomers to ask their views of how the leader's team is operating, as well as their thoughts about the larger organization. Consider the leader who makes a point of meeting one-on-one with the most highly regarded new hires after they have been with her firm for three or four months. These interviews typically involve the more senior hires but can also include junior newcomers. She wants to know their impressions before they become too acclimated to the company—in essence, she wants outsiders' views of the company as they get to know it. These discussions focus on the business but also on the organization's way of operating. She will ask questions such as these:

- What has impressed you about our firm, coming in as a newcomer? From what you have seen, what are the key strengths of the organization?

- On the other hand, are there things we do that you think we should stop or modify?

- How is this firm different from your past firm? Any insights into how we need to operate as a result of that comparison?

- What was your experience in managing the transition into our company? Did we make it easy in some areas? Hard in other areas?

- Do you have any questions for me about the firm or my leadership values?

- Any summary advice on how to improve our company?

A similar type of discussion with those leaving the firm can be helpful. This may be part of a more general exit interview about how the departing executive views the firm and the leadership group. These can be difficult conversations, depending on the dynamics of the departure and whether an individual is leaving to work for a competitor. But it is one more opportunity to surface disconfirming data. In particular, a departing team member may feel that he or she can now express to the senior leader his or her true views about other team members—both their strengths and weaknesses. An exit interview is an opportunity, if managed skillfully, to get honest feedback about your leadership impact, team, organization, and business. The feedback may be biased, depending on the motives of the departing executive, but it can also help a leader uncover his or her own blindspots about leadership team members.

In some teams, members are reluctant to criticize other team members to the senior leader because it may look petty or be seen as undermining their colleagues. Moreover, some leaders don't want people coming to them to complain about what others on the team should or should not be doing. I know of one CEO who felt he had too many individuals complaining to him about their peers. So one day, after hearing one team member describing a counterproductive thing another member was supposed to have done, the CEO told the first individual to hold his thought, walked down the hall, and brought back the individual being discussed. With the two team members in his office, the CEO then said to the complaining member, “Tell him what you just told me. Now, the two of you work this out and don't bring your issues to me.” This approach is effective in some cases in stopping the tendency of some team members to elevate issues that could be resolved directly with their peers. However, the senior leader needs to know about these issues when they can't be resolved at the team level and are negatively affecting the business and its key stakeholders (customers, employees, and shareholders). In some cases, leaders will want to seek out those who are dissatisfied to surface information that the leader will not get if he or she does not take steps to surface what people are thinking. One key is knowing whom to ask for input. I knew a manager who said he would deliberately seek out the most negative, sometimes paranoid, person in a group to get a more complete picture of what was occurring with his organization. I recall laughing at his point but also thinking there was some merit to it. Of course, this doesn't mean that everything this leader heard from the paranoid individuals was factual or even helpful—but he wanted the benefit of potentially uncovering what he would not get from others.

Leaders can also seek input from those outside the firm who have a contrary view of how the firm is operating or its future prospects. These could be industry experts or financial analysts who are outliers in having a perspective that is very different from the beliefs of those inside the firm. Warren Buffett, the legendary investor and CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, is a notable example of someone who engages outliers. He invited a hedge fund manager to his annual stockholder meeting in 2013—a manager who held a negative view of Buffett's firm. This individual, Doug Kass, was betting that Berkshire's stock would decline and was shorting it. Buffett wanted him to come onto the stage with him at the meeting and express his concerns in a lively give and take. Buffett was demonstrating his willingness to take into account contrary views and avoid the success trap that afflicts many prosperous firms and successful leaders.

Outliers can also be individuals within the firm who are seen as iconoclastic and, in some cases, difficult to work with because they challenge the status quo. Some leaders will deliberately search for these people within their own companies and spend time with them to better understand their points of view. Effective leaders also understand that the dominant culture in their firms often ostracizes such individuals and discounts what they have to say. In some cases, their views have little or no impact because they challenge the current mode of thinking and those who hold those views. Or, they become so frustrated that they leave the firm. This is not to suggest that the views of all outliers are inevitably helpful but, in some cases, they are surfacing opportunities and threats that others would rather ignore.17

Conduct Deep Dives in Targeted Areas

Another approach to collecting disconfirming data regarding your organization is to conduct what some call deep dives. Dan Vasella, former CEO of Novartis, comments that every leader needs to understand when his or her people can be fully trusted and when more information is needed (and thus the need for deep dives). He says, “you should know the people and then know when you let them totally do [it] and you can go to bed, close both eyes, and sleep deeply and well, and you know things are being really done extremely well—and maybe better than you can do it. And when you have to say, ‘No. This is not sounding right. It's not smelling right.’ And here, I want to understand. And I go deep in detail.”18

There are two types of deep dives. The first, as noted above, occurs when a leader seeks to understand why something is off track. In these situations, a leader will want to be particularly aware of how decisions are being made and by whom. Don't just ask about what's happened and how to fix it. Instead, ask what people were thinking as the decision was being made and which individuals or groups were driving the decision. Take the case of a leader who has several newly acquired businesses that are failing to meet revenue forecasts. While these businesses are not large compared to the firm's core business, they are important as future growth drivers. The senior leader asks for explanations from those leading these units and from others but is unsatisfied with the results. He decides he needs to do a deep dive to better understand what is going on in these groups. He then goes into each business unit and meets with key staff as well as gaining exposure to customers affected by the acquisition. He reaches his own conclusions as to the source of the problems and meets with leaders of the new units as a group to discuss his findings and necessary changes in how the corporation acts in acquiring, integrating, and managing new businesses.

It is important in conducting deep dives to look not only at what is said but also at what is not being addressed or talked about. Max Bazerman and Ann Tenbrunsel note that anyone who conducted a deep dive into the work being done at Enron by the accounting firm of Arthur Andersen may have seen people talking a great deal about making money but not talking about the importance of protecting Andersen's reputation by acting in a fully ethical manner.19 Some of the most damaging events occur when a leader or group fails to act on something that requires change. In a few cases, I have seen leaders who deliberately do not want to see what is going on at the lower levels of their organization because they are concerned about potential culpability if things go wrong. With sufficient distance, they can claim that they didn't know what was occurring in their own organizations or groups. A senior leader conducting a deep dive will want to read between the lines to see whether “things not talked about,” deliberately or not, are at the root of the issues he or she is exploring.

The second type of deep dive occurs when leaders bypass their organization's hierarchy to promote innovative projects within the company.20 These typically are growth projects that the leader believes are critical to the success of the firm, and as a result, the leader personally invests his or her authority and time to increase the likelihood of success. Steve Jobs was personally involved when Apple was developing music devices and a network of record labels to provide content. He rolled up his sleeves and immersed himself in the details of product design and the difficult negotiations with music companies. Deep dives of this type are necessarily limited to just a few, given the other demands a senior leader faces. But as Jobs and others have demonstrated, the impact can be positive both in improving a leader's understanding of what is occurring in these critical projects and in increasing the likelihood that the projects will be successful.

Perform Short-Cycle Reviews of Progress

Another technique to surface disconfirming data is to conduct frequent reviews of progress in targeted areas—resulting in what some call fast failures. In some firms, this involves a weekly review of the areas that the leader deems to be most important to the success of the firm. This was the case at Apple under Steve Jobs. He would meet each Monday with his leadership team to review progress on each of the firm's key products in development. This was possible because Jobs had streamlined the firm's product portfolio. It is also true that he had a passion for product design and believed that his team should be hands-on to ensure the new product met their standards. Jobs wanted his leaders to be fully aware of the status of each product and to provide input early and often. In other firms, these short-cycle reviews are done even more frequently. Pixar insists that the entire project team review the animators' equivalent of dailies at the end of each day (as happens in the filming on most live-action films). Ed Catmull, president of Pixar, describes the process as follows:

People show work in an incomplete state to the whole animation crew, and although the director makes decisions, everyone is encouraged to comment. There are several benefits. First, once people get over the embarrassment of showing work still in progress, they become more creative. Second, the director or creative leads guiding the review process can communicate important points to the entire crew at the same time. Third, people learn from and inspire each other; a highly creative piece of animation will spark others to raise their game. Finally, there are no surprises at the end: When you're done, you're done. People's overwhelming desire to make sure their work is “good” before they show it to others increases the possibility that their finished version won't be what the director wants. The dailies process avoids such wasted efforts.21

Pixar also attempted to create a culture that facilitated ongoing dialogue across boundaries—allowing information to flow in a more productive and timely manner. It did this, in part, by stating that any member of any department in Pixar should feel comfortable going to anyone in another department to solve problems or seize opportunities. My sense is that this norm was, in part, a reaction to what the firm's leaders had seen in other firms in which they worked, where going through “proper channels” was mandatory. In these firms, people needed to ask for permission before reaching out to those in other groups or risk damaging their careers. John Lasseter, in particular, experienced this early in his career when he worked for Disney. Pixar didn't want the organization's hierarchy to restrict the free flow of information across levels and boundaries.22

SURFACE DISCONFIRMING DATA ABOUT YOUR MARKETS

Leaders use a variety of techniques to identify disconfirming data in regard to their customers, markets, and competitors. In this section, I describe some of these techniques. As before, each leader needs to determine what will work best in a particular situation and corporate culture. Approaches to consider include the following:

- Identify and engage sentinels.

- Challenge your core assumptions.

- Conduct pre- and postmortems.

Identify and Engage Sentinels

There is some truth in the saying that the surest way to destroy a company is to give it ten years of unmitigated success.

Organizations are typically aware of emerging threats but, as noted earlier, often discount these threats. Time and again, new entrants are viewed as posing little threat and are then marginalized. Instead, leaders need to identify the areas or specific competitors that need to be monitored. One way of doing this is to identify a point person, or in some cases group, to be a sentinel responsible for collecting and analyzing data about the identified areas, including the actions of current and emerging competitors. The sentinel's role is to be fully informed of trends in the targeted areas and to be an advocate for appropriate concern around the threat that is emerging (or the opportunity that should be seized). An example of this is found at some PC firms, such as Dell, that were late to recognize the power of mobile computing to erode their business models. Dell may or may not have had ample data on the emerging threat; however, it is difficult to believe that the company didn't have internal or external groups sending up warning signals that Michael Dell and his team misinterpreted. In addition, the role of a sentinel is to be an advocate for necessary action, especially in the face of complacency.

Sentinels are the watchdogs for emerging threats that others may ignore. They can focus as well on specific competitors, particularly those that are new and seen by many as niche players in an industry. In some firms, a strategy group will collect competitive information, but it is often less visible than needed to promote action. Some firms, as noted earlier, assign senior executives to be strategic account managers for their largest customers. A similar approach can be taken in regard to major competitors, with a specific member of the leadership team assigned to become the sentinel who understands a specific competitor in depth, including the quality of its leadership team, the strategies it is implementing, and the progress it is making in key areas such as research and development. A leader may ask a small group of high potentials to study a fast-growing competitor and determine the rate of its progress and why it is taking market share from more mature competitors. The leadership team periodically reviews the competitors in a team meeting and discusses the implications for the firm's strategies and investments.

A variation on this approach is to ask how you would attack your own business if you were a competitor—knowing what you know about your firm, including both its strengths and weaknesses. Some leaders ask an external firm or a small group of high potentials within the firm to conduct this analysis and then present the findings to the leadership team. I have also seen firms ask a similar question but from the vantage point of a private equity firm. Using this approach, the question is, “What would a top-tier private equity firm do if they bought our firm and sought to maximize the value of their investment?” This question, if asked, needs to be viewed with some caution because it may result in short-term actions to maximize the value of a firm. But it can surface actions that should be debated further, such as spinning off a division that is undervalued as a result of being a small part of a larger enterprise or taking more aggressive cost-cutting measures to increase profitability.

Challenge Your Core Assumptions

The best leaders want colleagues who work, when needed, as supportive adversaries—not loyal accomplices.23 One approach is to make assumptions, which are often implicit. For example, in one meeting at a technology firm, a senior leader presented a strategy and made the comment that the firm's core technology platform had a five-year window before it would face significant competition. An outside board member asked him how he came to that conclusion and quickly realized that it was not based on any hard data but was reflective of what the presenter would like to happen. This approach can be used in a more deliberate manner when a leader asks people to change their assumptions and the implications of doing so.24 In some cases, this can be done to change the aspiration of the group and then determine what is needed to make that aspiration a reality. A leader might say to a team, “You are projecting a $10 million market within five years. I think this product has the potential to be much larger. What would be needed to make it a $50 million market?” A well-known story involves leaders in GE's nuclear division, who were developing a business plan in the period after the Three Mile Island disaster. They projected a period of slower but ongoing development of nuclear power plants. Jack Welch, CEO at the time, came back at them and said that they were delusional and needed to develop a plan that assumed no nuclear plants would be built in the United States in next several decades. He forced a rewrite of the plan, but this kind of change in direction can also be brought about proactively by asking people to alter their assumptions and develop plans that accommodate different scenarios. This is one version of a technique called scenario planning, in which different futures are imagined, including risks, and a firm's potential responses delineated. These scenarios can include disruptive events that are highly unlikely but potentially devastating if they occur, events such as new technological breakthroughs, economic shifts, or social changes. Many firms now include some form of risk assessment in their strategic planning process, and some, particularly in the financial industry, have a chief risk officer to assess risks of various types. These individuals bring their assessments and proposed mitigation plans to the leadership team and, in some cases, to the board of the company.

The need to challenge assumptions starts with the leader's own thinking, as evident in a famous story about Andy Grove, the former CEO of Intel. The firm's leadership had been debating a major shift in Intel's core business, moving from memory chips into microprocessors. Unsure of what to do, Grove framed a hypothetical question to his co-CEO Gordon Moore: “If we were replaced and new management came in, what would they do?”25 The answer, both agreed, would be to make the change they were resisting. Grove and Moore decided to move forward, and that decision opened the next chapter in Intel's phenomenal history of growth.

Conduct Pre- and Postmortems

Most people are familiar with the benefits of a postmortem review, which looks back and extracts lessons learned after a project is completed. The key in this technique is for the leader to instill a mindset of wanting to learn from experience and to extract lessons learned about what went well and what can be improved. A project or area is selected for the postmortem. A small group then examines, in detail, what was intended, what actually occurred, and the implications for future endeavors in this area. An example of this approach is a firm that looks at its efforts in emerging markets, which are new areas of investment for the firm. The experiences of the past five years are examined in detail, with an objective eye for lessons that can be learned from the experience. Perhaps the most graphic illustrations of how postmortems work are the investigations done after highly public tragedies, such as the Challenger and Columbia shuttle disasters or the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. However, this technique is also helpful even when the outcome was successful, as leaders and firms often lack awareness of why things went well and need to be sure they can replicate them in the future.

A model of this type of review is found in the medical profession in what is called the M&M (morbidity and mortality) conference. These meetings take place weekly in most academic teaching hospitals. The medical staff of the hospital gather and review what happened in the past week under their supervision and discuss the changes needed to prevent mistakes in the future. In some hospitals, the meeting can be attended by upward of one hundred people (surgeons as well as medical students). The leader of the conference introduces each chief resident, who goes over the facts of each medical case to be reviewed. A discussion ensues and agreement is reached on lessons learned and the changes needed moving forward. The key to success in these meetings is getting the facts out in the open and allowing for an honest dialogue that recognizes that mistakes will happen.26

I worked with a leadership team that had a history of underperforming on their product launches. Each launch faced a unique set of challenges, but the majority of cases involved an overall failure to fully meet projected financial targets over time. On looking at several of these launches, the team members concluded that they could improve the execution of the launches and made necessary changes in how the firm's R&D, marketing, and sales groups worked together (with more aligned goals, more regular communication, and designated liaison roles). But the larger insight was that team members always embraced the most positive projections for a new product. Those supporting the product aggressively sold it internally to higher levels of authority. The firm then accepted these projections, and no one took on the task of realistically assessing the likelihood of meeting such aggressive growth targets.

“We're looking in a crystal ball, and this project has failed; it's a fiasco. Now, everybody, take two minutes and write down all the reasons why you think the project failed.”

The postmortem technique has been proven to be valuable in a range of organizations, including the US Army, which refers to the process as an after-action review.27 However, it is prone to a number of pitfalls. First, people often don't want to look objectively at mistakes, for the obvious reason that individual and group reputations are perceived to be at risk. In these cases, people either distance themselves from the mistakes or blame others for shortcomings. Second, when firms are not skilled in conducting a disciplined and data-driven approach to looking at experience, they can draw conclusions based more on perceptions or opinion than on hard data. Third, some leaders and firms conduct the assessment but then fail to implement the findings. This pitfall is similar to that encountered by firms that conduct benchmarking analyses but then fail to act on the data they uncover. Instead, they find reasons not to act on the data and not to change the way they are operating. Each leader needs to look at ways to ensure that the postmortem process is yielding helpful data, and this process may require modifications over time to ensure that it does not become stale.

A related technique is the premortem, which occurs before a project is launched and focuses on thinking ahead about what could go wrong. Gary Klein, who is an advocate of this approach, notes that it promotes contrarian thinking in a highly productive way: “Before a project starts, we should say, ‘We're looking in a crystal ball, and this project has failed; it's a fiasco. Now, everybody, take two minutes and write down all the reasons why you think the project failed.’”28

One key to the success of this approach is to ground the discussion in what people know about the specific challenges they will face (because of the nature of the initiative or particular aspects of the firm's culture). The group should not generate general statements regarding the causes of a potential failure, such as, “We did not review progress in a timely and effective manner.” Instead, the group should be specific about what people know and fear could happen. This results in statements such as, “Our history is to wait and conduct reviews until too late into the program. This results in wasted time and resources, as well as a great deal of frustration for those working on a project. This project failed because we didn't review progress on a monthly basis with senior leadership.” Or, “In the past, we allowed ‘scope creep’ in many of our large projects. In this project we added feature after feature to the product, and it killed our timelines and cost objectives. We need to set the success criteria up front and not deviate.” After surfacing what could go wrong, a second task is to prioritize the project derailers. Not all threats are equal, and the group will want to identify the top two to three to address through preventive actions, as well those that need to be monitored over time.

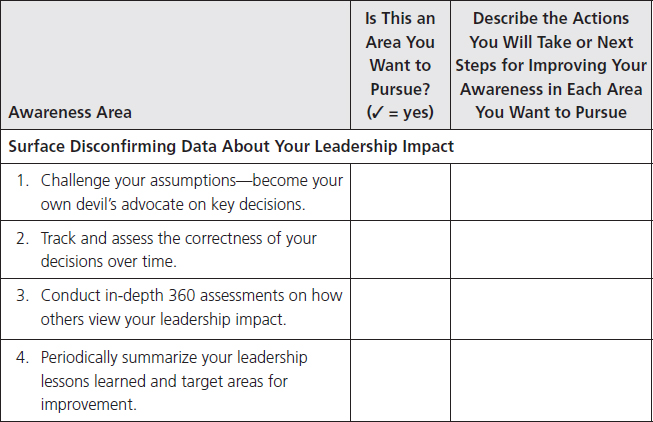

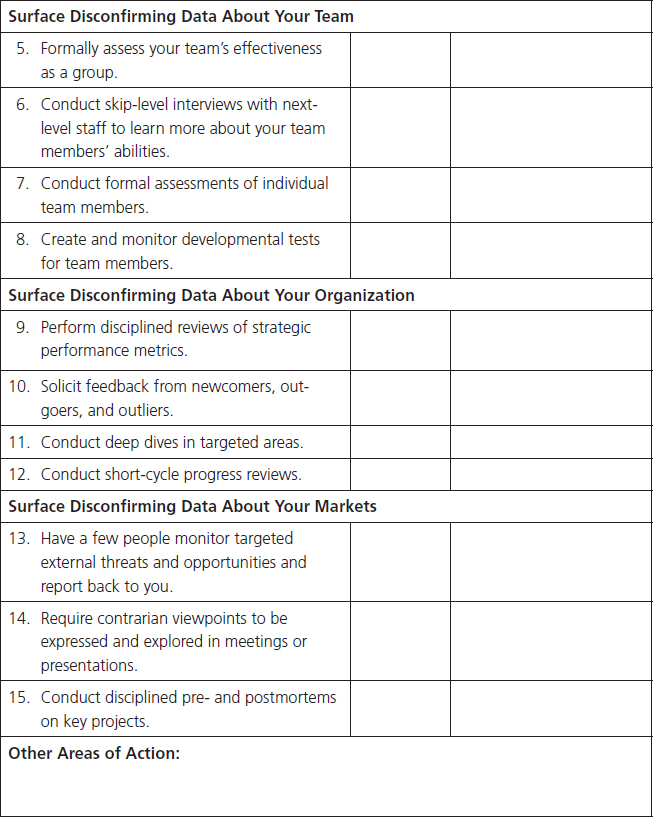

ACTIONS FOR SEEKING OUT DISCONFIRMING DATA

The following worksheet will help you surface disconfirming data about your own impact as a leader, as well as the beliefs you hold about your team, company and markets.

SEEKING OUT DISCONFIRMING DATA: SUMMARY OF ACTIONS MOVING FORWARD