Change – what can go wrong and how to do it right

Abstract.

Leaders, staff, goals and time are the four major reasons for a change project to go wrong. Leadership style and staff behaviour are linked and goals and time schedules of deliberate large-scale change projects, which are often unrealistically short, affect leadership style as well as staff behaviour. All four aspects need to be considered thoroughly before the implementation and during the realisation of major change projects.

9.1 Leaders

‘Not many years ago good leadership equalled good and smooth administration’ (Pors and Johannsen, 2003). Nowadays, ‘Leadership is about facilitating, guiding and managing change’ (Beerel, 2009). ‘Leading change is one of the most important and difficult leadership responsibilities’ (Yukl, 2010).

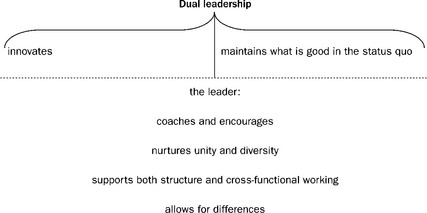

Pugh talks about ‘a type of dual leadership’ (see Figure 9.1 1) which is a necessary basis on which to successfully accomplish change projects, which means that leaders have to be innovative and at the same time able to maintain what is good in the status quo.

Leaders and their leadership style are essential aspects of every deliberate large-scale change project. As can be seen in Figure 9.1, leaders shouldn’t only be living in the now, but have a vision and be innovative. They need to balance between the present and the future (Moropa, 2010).

If leaders only stick to the ongoing processes they cannot lead their team members through the difficulties and challenges of a deliberate large-scale change that might be provided from the outside. They cannot then act as role models, which is one of their tasks during change processes.2 Leaders are the catalysts for change (Pors and Johannsen, 2003) and should see themselves as such.

All in all deliberate large-scale changes can only be successful with a strong leadership team that understands and embraces the vision of such a transformational change (Nussbaumer and Merkley, 2010). For this leaders have to be open and willing to change themselves, and they should have the ability to cooperate with, to motivate as well as to inspire their team members (Pors and Johannsen, 2003). They need to encourage their team members:

![]() to continually question the ongoing usefulness of established ways of thinking; and

to continually question the ongoing usefulness of established ways of thinking; and

![]() to explore alternative and new ways of working (Morgeson et al., 2010).

to explore alternative and new ways of working (Morgeson et al., 2010).

Furthermore, to carry out a change project successfully the superiors of the leaders responsible for a major change project should have faith in them, give them ‘real’ authority and offer support throughout the entire change project.

9.2 Staff

‘To remain competitive libraries must cultivate intrinsically motivated, high-performance employees …’ (Rolfe, 2010). Librarians need to adapt to an environment of rapid and complex changes in the ways in which information is organised, accessed and used now and will be in the future (Smith, 2011).

This rapid pace of change in the environments of libraries prompts leaders to develop teams of highly motivated, confident, creative and flexible high-performance employees (Rolfe, 2010). Leaders should get their team members to scrutinise new technologies and trends as a habit and the library should be conducting user surveys on a regular basis (Moropa, 2010).

‘The greatest challenge has been to manage library staff fears and expectations’ (Nussbaumer and Merkley, 2010), especially as resistance to any kind of change is a common phenomenon for individuals (Yukl, 2010).

It is often said that older team members especially are against changes in their library and that it might be difficult if there is a relatively high percentage of older people working in the department where the change process results in new tasks for everybody.

Practical experience shows that resistance is not directly or always dependent on age. In one library, for example, team members who were only in their forties were refusing to perform new tasks even after participating in professional training.3 ‘Complacent staff members within an organisation [independent of age] tend to want to maintain the status quo, especially when the organisation is successful or doing well’ (Moropa, 2010).

Positive peer pressure from the team might help leaders handle those - older as well as younger - team members who are showing resistance, as it is not easy to force people to work. This is especially the case in the public service where (at least in Germany) it is virtually impossible to dismiss members of staff. Nevertheless, it sometimes helps if during a major change quite a number of the old heads of departments or teams are retiring.4

Some difficulties in the change processes in libraries might arise from team members’ job-related self-understanding. This means, for example, that staff working on high-quality tasks at the information desk might not want to be moved to another work location because of worries about the need to do new tasks that seem (in their opinion) to be inferior to their previous work.

One might also find the old-fashioned red tape of librarians difficult to manage throughout a change process. To solve this obstacle leaders themselves should be willing to do inferior work to show those team members that this is something normal which is required of them.5

Not every team member will be busy and working hard to support the change process or to help others with their tasks. These people still have to be integrated into the work that needs to be done. These team members might sometimes act as so-called ‘class clowns’ though in doing so they can be good support for the change process. Even if this wasn’t their intention they may help the other team members to see the funnier side of things and so boost morale.

Others who don’t want to support the change process - often those who are generally more inefficient workers than their team colleagues - are quite often on sick leave during the change process. However, ‘it is obvious that the library is totally dependent upon the human beings that work there, their behaviour, their work methods, their endurance and the need to complete tasks’ (Massey, 2009). Therefore it is important to convince the staff of the need to change. One approach is to find change agents or promoters to support the top management and other leaders in this difficult task. Such promoters should be supportive of the plans for major change and should be able to share their optimism with the other team members (Nussbaumer and Merkley, 2010).

It is also possible to get the staff to participate in the change process through encouragement from the leaders. This is often greatly appreciated by the staff because daily routines usually become tedious after a while (Massey, 2009).

9.3 Goals

Libraries that want to provide high-quality services, relevant for their users and responsive to their needs, must be flexible in their goals as well as their actions (Smith, 2011).

‘Knowing where to begin is one of the key challenges of change’ (Nussbaumer and Merkley, 2010). For this the top management and the leaders need to be clear not only about the nature of the problem but also about the objectives and goals of this change (Yukl, 2010).

This means that strategies and goals need to be identified for major changes. Only then are the members of staff able to move forward in the following contexts:

9.4 Time

‘Just as it takes miles to turn a supertanker at sea, it often takes years to implement significant change in a large organization’ (Yukl, 2010). ‘Achieving change is a long-term and complex process’ (Smith, 2011).

As could be seen in section 3.1, regardless of the size of the library or the affected department, the timeline for a change project is very often tight, even if practitioners say that it is not unrealistic to expect it to take five years for a major change in a library to take hold (Nussbaumer and Merkley, 2010).

It is important to meet regularly during the change process, so that the team members can get the information they need and are given the chance to contribute their own ideas and ask questions concerning the alterations. However, as time is often tight in a change project, there should always be a good reason to call a meeting, for example to pass important knowledge on to the team members or to discuss a problem. Meetings should be kept short, so that everybody can go back to work as quickly as possible (Massey, 2009).

1.For this type of dual leadership see Pugh (2007).

2.Leaders of all hierarchical levels need to be role models and should – as those responsible for the change – live and embody the new value system (Krüger, 2009).

3.This happened, for example, after one of the change projects to implement the new RFID technology in the library was completed and all team members had to perform new tasks and duties.

4.As was experienced during the deliberate large-scale change which is described in section 5.3.

5.For one example see section 4.2.2. Also the author’s own experiences working as a deputy library director with the newly put together team ‘Archives and Copying’ and in the old departments ‘Archives/Magazine’ and ‘Copying’ for two weeks showed that it is helpful for mutual understanding to work as a leader with those affected by a major change.