Chapter 10

Establishing a Continuous Improvement Organisational Structure

In This Chapter

![]() Sorting out a continuous improvement framework

Sorting out a continuous improvement framework

![]() Adhering to standards while remaining flexible

Adhering to standards while remaining flexible

![]() Taking a look at the continuous improvement group

Taking a look at the continuous improvement group

![]() Summarising the roles of various stakeholders

Summarising the roles of various stakeholders

In this chapter we discusses how to organise the continuous improvement activities that may either form one of the parallel transformation workstreams or follow on after the transformation has been undertaken (whether fully or partially).

Setting Up the Structure for Continuous Improvement

Continuous improvement is both an integral part of and a downstream activity following on from business transformation.

- A continuous improvement programme manager (or managers) responsible for the integrity of the programme and ensuring a consistent professional approach across the organisation.

- A continuous improvement programme management office responsible for supporting and administering the programme, including organising training for those involved and tracking the progress of the constituent projects.

- Continuous improvement experts, typically known as Master Black Belts, responsible for providing expert analysis and coaching support in the selection and execution of projects.

- Lean Six Sigma project leaders, known as Green Belts (if part time) or Black Belts (if full time). Green Belts tend to lead those projects scoped within an individual function or department; Black Belts usually lead the more complex and longer cross-functional projects spanning the organisation.

Depending on the scale of the transformation, the roles of the transformation programme manager and of the continuous improvement programme manager may be assumed by the same person or different individuals. If different, the continuous improvement programme manager is likely to report to the transformation manager. Likewise, the respective programme management offices may be integrated or otherwise separate but tightly interconnected.

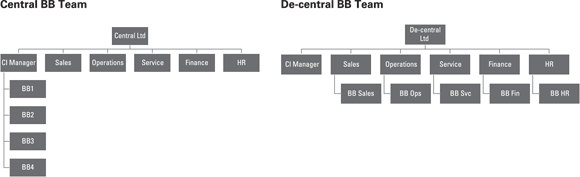

The size of the organisation and the scale of the transformation will be important factors in determining whether the continuous improvement organisational structure is centralised or decentralised (see Figure 10-1). Ultimately, though, the style and culture of the organisation is likely to be the biggest determinant. This is perhaps best illustrated using some examples.

Figure 10-1: Centralised versus decentralised continuous improvement organisational structure.

Contrasting the two approaches, the determining factor for the organisations appears to be the number and choice of continuous improvement projects selected. In the first example, widespread continuous improvement deployment occurred and the majority of continuous improvement projects were (single) functional in nature; cross-functional projects were managed through the transformation structure. In the second example, the continuous improvement focus was on cross-functional projects and the organisation had yet to expand its programme to smaller-scale improvement activities.

Creating Standards while Maintaining Flexibility

Irrespective of whether you adopt a centralised or decentralised structure, it’s essential that a common standardised approach is taken to continuous improvement across the organisation. Without it, no cross-functional leverage will be possible and pockets in which continuous improvement stalls or progresses spasmodically are likely to exist – in short, a recipe for chaos and limited variable deployment.

The following actions are key to creating your desired standardised approach:

- Agree and use standard continuous improvement terminology (the ‘lexicon’) across the organisation. Over the years your organisation may well have developed its own jargon and words for certain things. ‘Champion’ or ‘sponsor’, or other words and phrases, may already have well-established meanings that are different from their typical use by other organisations adopting Lean Six Sigma. If that’s the case, define your continuous improvement terminology carefully and apply it across the enterprise to avoid any confusion of meaning.

- Develop and deliver common Lean Six Sigma training (and coaching support) to all those involved in continuous improvement. Ensure that you agree and organise a common training curriculum for staff involved in the transformation process. Of course, different levels of training will be needed for various groups (executive sponsors, project champions, Black Belts, Green Belts, Yellow Belts and so on). Depending on your needs, you may consider customised or generic training programmes, but you need to ensure, for example, that all Green Belts receive training on the same curriculum and are trained on the same core range of tools and techniques irrespective of what part of the organisation they work in.

A point of qualification here: it may be appropriate to distinguish the curricula for ‘Manufacturing’ Green Belts and ‘Service/Transactional’ Green Belts. Some specific tools and techniques are more relevant to each group, in addition to those common to both. If you want your Green Belts to be able to support any part of your organisation, create a curriculum common to both. If that’s not the case, you may feel it appropriate to have two ‘flavours’ of Green Belt training.

If your organisation operates in many different countries, consider appointing different internal or external trainers to conduct the Lean Six Sigma training. However, be aware that different external providers may have their own materials and follow a different curriculum. You need to ensure that a common curriculum is adopted across the organisation, either by encouraging external providers to adopt common materials or by adapting or customising external providers’ material for your own organisation.

- Certify Yellow, Green and Black Belts (and possibly champions as well) to a common standard. Learning how to lead Lean Six Sigma projects doesn’t end as you come out of the classroom, it continues through being applied to real improvement projects. Hence a Green Belt, for example, is not fully fledged until they’ve undertaken their training and successfully applied it to deliver at least their first improvement project. It makes good sense to recognise this combination of learning and project experience through some kind of formal ‘certification’, which will likely also include an examination to confirm the individual’s learning. Internal certification schemes can be developed, but nationally and internationally recognised external Lean Six Sigma certifications are also available from the British Quality Foundation (BQF) and the American Society for Quality (ASQ), for example. The bar is set quite high for such certification and it’s an excellent way to both recognise achievement and ensure common high standards across the organisation.

- Implement a formal Lean Six Sigma certification scheme appropriate to your organisation. Unless good reasons exist for doing otherwise, adopt a nationally or internationally recognised external certification scheme.

- Standardise continuous improvement project tollgate reviews. Individual Lean Six Sigma projects should be reviewed after each DMAIC phase. In essence, two types of review exist – a business review, where the intent is to verify whether the project is on track and on time to deliver the chartered improvements, and a technical review to validate that the methodology and appropriate tools have been properly used and correct conclusions drawn. Both are important, and are often combined, but it is the technical review that assures the common standard approach across the organisation. The previous bullet point described certification, but in essence the assessment review after the project has been completed could be regarded as the ultimate technical review of last resort – the certifier has to verify that the Green (or Black) Belt has indeed followed the methodology and used the appropriate tools throughout the entire project.

- Facilitate best practice transfer and learning across the organisation. Adopting common standards is not about securing the least common denominator; rather, it’s about seeking common high standards and continuous learning and improvement.

- Actively seek to identify and transfer best continuous improvement practice across the organisation. Consider such vehicles as project fairs, recognition events, internal continuous improvement conferences and the like to facilitate this process.

Introducing the Continuous Improvement Group

Typically, the continuous improvement group will include an overall continuous improvement programme manager, some specialist support staff, both administrative and professional experts (Master Black Belts) and Lean Six Sigma project leaders (whether Green Belts or Black Belts). Project champions may also be considered part of the continuous improvement group.

The corporate continuous improvement group

We’ve considered the need for establishing common continuous improvement standards while maintaining flexibility. This is certainly a core part of the role of the corporate continuous improvement group. The corporate continuous improvement programme manager will typically be responsible for:

- Providing continuous improvement leadership across the organisation, and identifying and communicating the appropriate methodologies and toolkits.

- Supporting the corporate senior leadership team on all matters relating to continuous improvement.

- Organising training and coaching for the project champions and team leaders (the Belts).

- Organising an appropriate programme governance system covering the selection of projects through to their steering and completion, together with effective handover into the normal operating ‘business as usual’ and downstream process management.

- Communicating information about continuous improvement throughout the organisation, including the recognition of successful projects, and the sharing and transfer of best practices.

- Leading a small central continuous improvement programme management office that provides support and administration for the programme.

- Working very closely with the transformation programme manager during the transformation process and being responsible for the constituent continuous improvement workstreams.

The continuous improvement programme management office is likely to include a small group of support staff responsible for:

- Organising the logistics for Lean Six Sigma training and project/programme reviews.

- Maintaining the project tracking and governance systems.

- Organising other continuous improvement events and managing day-to-day continuous improvement communications.

Depending on the degree of centralisation, a small group of Black Belts/Master Black Belts may also be necessary, responsible for providing Lean Six Sigma technical support across the enterprise, including:

- Leading the more complex continuous improvement projects, which might be cross-organisational and involve the customer or supply chains, or constitute an end-to-end process design.

- Providing coaching and advanced analysis support to other projects occurring elsewhere in the organisation.

- Leading the deployment of specific segments of the continuous improvement programme.

- Leading the mainstream internal Lean Six Sigma training programmes.

Divisional/regional continuous improvement groups

The decentralised continuous improvement groups will normally include the Green Belts responsible for leading projects within their own areas of responsibility on a part-time basis, together with their project champions.

Depending on the degree of decentralisation, the small cadre of Black Belts (and perhaps Master Black Belts) may be hosted within divisional/regional continuous improvement groups. At least some of these people will almost certainly have programme management responsibilities for the projects being undertaken in their own division or region as well as other responsibilities listed in the previous section. They’ll be responsible for ensuring that corporate continuous improvement standards, methodologies and toolkits are used, but not for determining them in the first place.

Even if this cadre is decentralised, the more senior Black Belts and Master Black Belts will still form a virtual team across the organisation and will in effect operate within a matrix of responsibility; although directly reporting to their local divisional or regional management, they’ll also have a functional reporting line to the corporate continuous improvement programme leader.

Understanding the Stakeholders

Earlier sections in this chapter introduced these roles; here, we briefly summarise their responsibilities and any other relevant information.

Business leader

The business leader has overall responsibility for the part of the organisation assigned to them, both for its longer-term strategic development and day-to-day operational performance. They’re responsible for the people reporting to them within that part of the organisation and for its overall management. The business leader also sponsors and leads any transformation and/or continuous improvement programme relating to that part of the organisation.

Champion/sponsor

The project champion is the manager who commissions the continuous improvement project to improve a process important to them, probably within their sphere of responsibility, and to address an associated performance problem or opportunity. They’re involved in selecting the project and the team members for it (including the project leader – Black or Green Belt). As the project progresses, the project champion continues to be involved by:

- Providing strategic direction to the team.

- Developing the first draft of the improvement charter and ensuring the scope of the project is sensible.

- Remaining informed about the project’s progress and taking an active involvement in project and risk reviews.

- Providing financial and other resources for the project team.

- Helping to ensure the business benefits are realised in practice.

- Being prepared to stop the project if necessary.

- Helping to get buy-in for the project across the organisation.

- Ensuring appropriate reward and recognition for the project team in the light of its success.

The programme sponsor is the senior leader who commissions the overall continuous improvement programme and is ultimately responsible for its success. They’re responsible for:

- Getting buy-in from the organisation as a whole and its external stakeholders.

- Establishing the continuous improvement programme and chairing the programme reviews.

- Providing financial and other resources for the programme.

- Being prepared to re-steer/re-direct the programme as and if necessary.

- Ensuring appropriate reward and recognition for those involved across the programme.

Value stream manager

Interchangeably also known as the ‘process owner’, this individual is responsible for the process or value stream. They need to ensure that the process is designed and managed to meet customer and stakeholder CTQs (critical to quality parameters).

Functional manager

The functional manager is responsible for an entire business function such as finance, operations, marketing or HR, or for a department within a business function. They’re responsible for the performance of the processes within their area on a line or operational basis. Many such processes may exist, but it’s likely that the end-to-end value stream will cut across several functions or departments. The functional manager is thus responsible for operating processes consistently in line with the design required by the respective process managers, and for contributing towards any process improvement activity commissioned by them.

In essence, functional managers are responsible for the operation of a vertical slice of the organisation, whereas value stream managers are responsible for the end-to-end processes across the organisation. Clearly, functional managers and value stream managers need to work constructively together for both day-to-day operational management and transformation and continuous improvement to be effective.

Lean Six Sigma Black Belts

Black Belts are expert continuous improvement practitioners, whose role is to lead complex projects and provide expert support, using appropriate tools and techniques, to the various project teams within their scope of responsibility. They’re often from different operational functions across the company, joining the Black Belt team from customer service, HR, marketing or finance, for example. The Black Belt role is usually full time and often for a term of two to three years; after this period, they return to operations. In effect, Black Belts become internal consultants working on improving the way the organisation works and changing the organisational systems and processes for the better. The Black Belt team may be centralised and report directly to the continuous improvement programme manager, or it may be decentralised and the various divisions, regions or functions will operate as a virtual team. This decision will depend on the culture of the organisation and the scale of the continuous improvement programme.

Black Belts will typically receive about four weeks of Lean Six Sigma training over a period of some months. In addition to the foundation training that Green Belts receive (see below), Black Belts will develop a solid understanding of all the main statistical and change management tools, and will become effective practitioners in the use of statistical software.

Lean Six Sigma Green Belts

Green Belts are trained to use the basic Lean Six Sigma tools and lead the more straightforward projects. They’re normally part time and devote the equivalent of approximately a day a week (20 per cent of their time) to Lean Six Sigma projects. They’re usually mentored by a Black Belt.

Green Belts continue to undertake their usual day job, the idea being that the improvement projects they lead will be related to their normal areas of responsibility. All managers have the responsibility for not only undertaking their job but also to improve the processes therein. In that sense, the part-time Green Belt role is already effectively part of their normal job; they’re just being trained and empowered to improve those processes using the best practice approaches inherent in Lean Six Sigma. They will, by the very nature of their role, be decentralised across the organisation and remain in their normal host functions, divisions or regions.

Green Belts’ basic Lean Six Sigma training typically lasts about a week and covers lean tools, process mapping techniques and measurement. It also provides a firm grounding in the DMAIC methodology and the basic set of statistical tools. Some Green Belts will also receive about a further week’s training to cover the full body of knowledge required for ASQ certification, or to learn how to apply the more common statistical tools.

A workstream is a clearly defined and scoped sub-programme of change within the overall transformation or a programme of non-transformational change following on from it.

A workstream is a clearly defined and scoped sub-programme of change within the overall transformation or a programme of non-transformational change following on from it. The continuous improvement workstream has itself to be programme-managed as part of the overall transformation effort, and you need to establish a continuous improvement organisational structure that’s integrated with the transformation during that phase and continues afterwards. The components of the continuous improvement organisational structure are:

The continuous improvement workstream has itself to be programme-managed as part of the overall transformation effort, and you need to establish a continuous improvement organisational structure that’s integrated with the transformation during that phase and continues afterwards. The components of the continuous improvement organisational structure are: A UK insurance company that’s a subsidiary of a global group will have a centralised transformation programme management office responsible for centralised aspects of continuous improvement. For decentralised continuous improvement, individual business functions will have their own continuous improvement leaders and (part-time Green Belt) project managers; widespread continuous improvement activity will take place. In contrast, an otherwise similar competitor with a smaller-scale continuous improvement programme operates centralised continuous improvement, with full-time Black Belt project managers located in the central programme management office.

A UK insurance company that’s a subsidiary of a global group will have a centralised transformation programme management office responsible for centralised aspects of continuous improvement. For decentralised continuous improvement, individual business functions will have their own continuous improvement leaders and (part-time Green Belt) project managers; widespread continuous improvement activity will take place. In contrast, an otherwise similar competitor with a smaller-scale continuous improvement programme operates centralised continuous improvement, with full-time Black Belt project managers located in the central programme management office.