Chapter 7

Understanding Business Breakthroughs and Fundamentals

In This Chapter

![]() Reviewing your business initiatives

Reviewing your business initiatives

![]() Recognising business breakthroughs

Recognising business breakthroughs

![]() Focusing on business fundamentals

Focusing on business fundamentals

![]() Considering key performance indicators

Considering key performance indicators

Once you have in place your Transformation Charter, an assessment of your readiness for the intended transformation programme, a suitable approach to administering and governing it, and an understanding of the vital few objectives that will be central to the transformation, you are ready for the next stage. You now need to more clearly separate out the professional day-to-day management of the ongoing business from that of the transformation programme, and to establish the appropriate approach to deploying your transformation efforts.

Avoiding Initiative Overload

Most organisations seem to suffer from initiative overload. There’s almost always too much going on and insufficient time and other resources to do the day job and handle all the initiatives that either come down from top management or are imposed by external stakeholders.

You can use various capability maturity assessment methods to review initiatives, but conducting this review is always best done through a facilitated senior leadership workshop. Obviously, you can simply review the initiatives as a separate exercise, but doing so is unlikely to be as effective.

Over time, all organisations build up clutter and then need to take stock and remove what’s surplus to current requirements and tidy up what remains. The situation is just the same with initiatives.

Recognising that more is less

A practical limit exists to what anyone can do in any given period of time. If your list of things to do is too large, many of those items won’t get done, but that doesn’t stop you worrying about doing them. You may become trapped in a vicious circle, in which you cannot focus on things you can achieve because you’re spending too much time worrying about those you can’t. Having too many things to do may encourage you to do things piecemeal even when several items are interrelated, which results in wasted effort because you potentially carry out the same activities more than once if they relate to different items on your list. You may also risk doing things in the wrong sequence, which may result in rework.

The logical thing to do is to step back and review the list of things to be done, rationalise them by removing overlaps and duplications, and re-sequence them in an appropriate new order. Of course, you also need to remove from the list any items that have been overtaken by events or are of dubious benefit. Now more is less and less is more – in the sense that more is likely to be actually achieved with a shorter rationalised and prioritised list than a longer rambling one. And so it is with organisational initiatives.

Weeding out unnecessary initiatives

Of course you can simply list all the initiatives, and review and prioritise them. But doing so misses a key point – that many of them may no longer be necessary or appropriate. We’ve run many facilitated workshops with senior leadership teams using the EFQM Excellence Model framework (see Chapter 5) to help them self-assess their management system. Inevitably, as the leadership team members work together and discuss the entire picture (and not just those aspects for which they’re individually responsible), they become aware of all the initiatives, current and planned, and where they fit (or don’t) within their management system and the organisation’s desired future state. Time after time these senior leaders have realised that many of their cherished initiatives are no longer relevant or are simply parts of a bigger picture and can better be reconstituted in a more rational way with different priorities. The key point to note here is that such workshops aren’t directly focused on rationalising initiatives; that happens almost coincidentally as a result of their collective understanding of what the organisation’s real priorities need to be.

Ideally, this review should be integrated with your review of readiness for transformation.

Avoiding succumbing to scope creep

Scope creep is the natural tendency to attach additional aspects to projects for seemingly good reasons – perhaps you forgot something or an event triggers the need for some new detail. Applying the principle of ‘more is less’ here suggests that scope creep left unchecked risks compromising your ability to effectively focus on the real things that matter for the success of your intended transformation.

Identifying Business Breakthroughs

In this section we consider how breakthrough differs from ongoing day-to-day management and how many breakthroughs you can practically handle. Breakthrough objectives are those intended to achieve a dramatic rather than gradual improvement in performance, and require a consistent, sustained and focused effort that’s synergised and synchronised across the organisation (breakthrough objectives are covered in Chapter 4). Breakthrough activities are those associated with such objectives and are likely to make significant changes to the ways in which an organisation, department or key business process operates.

Distinguishing breakthroughs from daily management

The business transformation may be vitally important to you but you can’t afford to take your eye off managing the rest of the business as the transformation progresses. Accordingly, managing these two aspects separately makes good sense.

In this context, daily management refers to the ongoing operation of the organisation, delivering products and services to its customers, and managing the relationships it has with its various constituent stakeholders. People still need to be employed, engaged and empowered to develop products, deliver those products and provide support to their customers – internal or external. The supply chain still needs to be managed, and all the everyday processes and activities need to take place to ensure that the business continues to survive and prosper. Short-term goals still need to be met and budgets adhered to. Anticipating success tomorrow as a result of the transformation doesn’t apply; today’s customers still need to be served, today’s staff and suppliers still need to be paid, and today’s investors and shareholders still need to be rewarded. Tomorrow’s daily management may well look different after the transformation, but you still have to deal with today’s version first.

Managing today’s business through managing by process is the best approach to daily management. Managing through process means understanding today’s processes, assigning process owners, and having key performance indicators (KPIs) in place and monitored with an appropriate scorecard; we go into further detail in the ‘Establishing Key Performance Indicators’ section later in this chapter. Associated gradual continuous improvement using Lean Six Sigma tools and projects is also a key component of effective daily management – not all improvement needs to be dramatic.

Irrespective of whether your organisation is managed by process, value stream or function (such as operations, finance, HR, and so on), daily management requires continuity and a separate focus during the transformation process. We discuss further organising for ongoing continuous improvement in Chapter 10. We also consider organising the governance system for transformation in Chapter 6, and Chapters 9 and 13 go into more detail on organising the separate transformation streams.

Working out how many breakthroughs you can handle

In short – only a very limited number. The ‘more is less’ thinking applies here too. If you try to handle too many breakthroughs, the resources (people and time) required will detract either from managing them effectively or from undertaking professional daily management. If you try to handle too few breakthroughs, or breakthroughs too limited in scope, you won’t see the dramatic change in performance you’re seeking. But attempting to handle more than two or three real breakthrough objectives at any one time can lead to the initiative overload we describe earlier in this chapter.

Determining the Business Fundamentals

Much of the organisation’s time must be devoted to keeping the business running; that is, carrying out the value-adding activities of the key business processes that fulfil the organisation’s purpose. These are the business fundamentals.

Maintaining a routine

Because routine tasks require much less thought you can save your mental effort for those things that aren’t routine. That’s the idea here – you need to concentrate the organisation’s efforts on the breakthrough you’re seeking, but you also have to keep the everyday going; the company still has to satisfy today’s customers and pay its bills. So if you can standardise the day-to-day stuff, you can have it both ways: carrying on business professionally and profitably while planning and executing the transformation process.

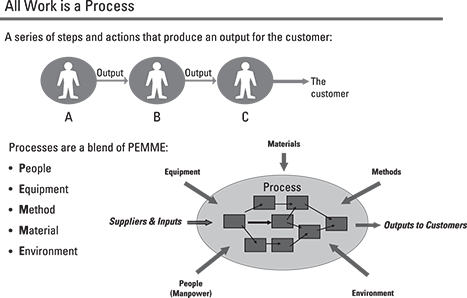

Since all work is a process, as illustrated in Figure 7-1, in principle all you need to do to manage the organisation’s routine is to manage its processes.

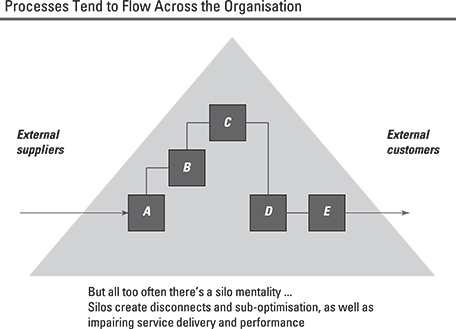

Too often organisations are managed functionally in silos – going up and down the organisation – whereas the key processes go across the organisation if they are to deliver to the customer what they want, as illustrated in Figure 7-2. You need to manage by process or value stream rather than by function if you want to stay on top of day-to-day routines.

Figure 7-1: All work is a process.

Figure 7-2: Processes tend to flow across the organisation.

Managing the key processes

A process is managed when:

- It’s owned

- It has a clear customer-focused objective with prioritised customer requirements (the CTQs – ‘critical to quality’ issues that must be met for the customer to be satisfied)

- A process map is in place documenting how the process is expected to be carried out

- An effective data collection plan exists, balancing input, process and output measures – and that data is being collected and used to monitor and control the process

- It’s stable and only affected by random/common cause variation

- It meets customer-focused objectives (CTQs) or an improvement plan is in place to make sure it does so

- It’s been error-proofed to minimise the risk of it losing control or failing to meet CTQs

- A control plan exists to ensure that it’s appropriately maintained

A process is professionally managed only when all of these requirements are met. Clearly, managing a process requires significant effort; you thus need to focus on just those key processes essential to the organisation’s success. Processes improved using Lean Six Sigma tools should be in a managed state by the time the control phase has been signed off. A process doesn’t necessarily need to be improved before it can become a managed process – but it does help!

Process owners

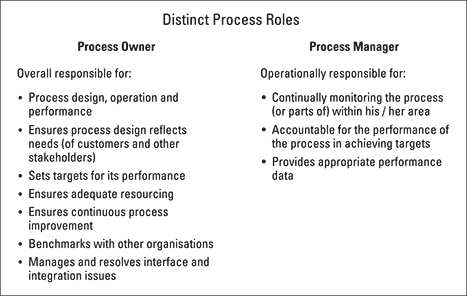

Figure 7-3 identifies the different roles of the process owner and process manager.

While only one process owner can exist there may be several process managers, as the same process may operate in different parts of the business or in parallel with different groups (for example, production cells or self-managed work teams) focusing on different products or customers. Having one owner with overall responsibility for the process’s design, performance targets and improvement enables standardised consistent operation across the organisation.

Figure 7-3: The distinct roles of the process owner and process manager.

Usually the process owner will be a named individual; however, a collective group of leaders may act together as the process owner. In this case there’s still just one process owner, albeit in the form of a group of people formally acting together.

The process architecture

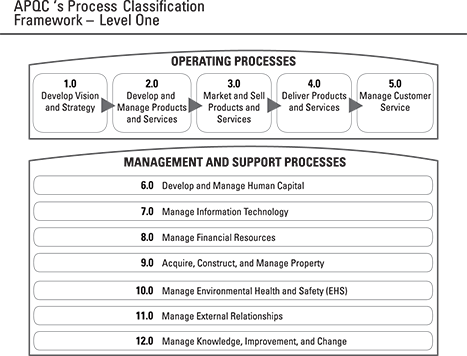

The process architecture is how the collective of key processes is configured to support the organisation. It can be expressed as a high-level map showing which processes are recognised as key to the business, how they relate to each other, and which people are the process owners. Some processes will be common to all businesses (for example, ‘managing people’), whereas others will be specific to certain types of organisation (for example, ‘manufacturing products’ is appropriate for a manufacturing business but probably not to a service sector organisation). Some processes assume much greater importance in some organisations than in others; for example, ‘manage compliance’ assumes greater significance in a tightly regulated sector such as pharmaceuticals or financial services than it might in logistics. Figure 7-4 shows the standard framework developed by the APQC (American Productivity and Quality Center), which you can use as a starting point to develop your own process architecture.

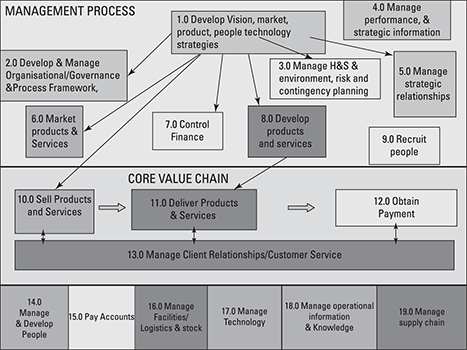

Figure 7-5 shows an example of a configured process framework for one of the authors’ organisations, Catalyst.

Figure 7-4: AQPC’s generic process architecture.

Figure 7-5: Catalyst’s process architecture.

Establishing Key Performance Indicators

Each managed process should have a balanced set of input, output and in-process measures. The output measures are lagging indicators (that is, measures that report after the event or transaction has been completed) that indicate how effective and efficient the process is – the extent to which it meets the requirements of its customers and of the business. The input and in-process measures are leading indicators (that is, measures that report before the event or transaction has been completed) that should enable the process owner to determine whether the process will continue to deliver the desired output. These measures collectively comprise many of the key performance indicators of the enterprise and will be included on the organisation’s scorecards and dashboards.

Additional measures may appear on the organisation’s top level scorecard, for instance customer satisfaction indices that derive from stakeholder perception rather than directly from the processes. Nevertheless, the process information on that scorecard will essentially be comprised of key performance indicators from the key managed processes.

Deciding on the approach

The scale of the transformation being sought, the period available for undertaking it and the state of ongoing daily management are all factors that need to be taken into account. In relation to transformation and the alignment of constituent activities, you can achieve a quantum leap in performance by:

- Focusing on just one or two breakthrough objectives but then deploying the associated activities across and throughout the organisation in a tightly aligned manner, or

- Ensuring that you progress all business objectives across a wide front in as consistent a manner as possible using alignment mechanisms that are less demanding, but accepting that the resulting alignment will be less precise, or

- Creating a suitable combination of these two approaches.

A number of different mechanisms have evolved or been developed over the years that progressively more tightly align objectives and actions; these include management by objectives, the balanced scorecard and Hoshin Kanri (originating in Japan but more commonly known in the West as policy deployment or strategy deployment. See the later section ‘Understanding the notion of Hoshin’). Before we look at these, however, let’s take a small diversion to consider a ‘softer’ mechanism that aligns the behaviours of people and, indirectly, their actions and activities.

Acknowledging the value of values

Having commonly agreed company values in place which are consistently practised is a powerful alignment mechanism that works throughout the culture of the organisation. Rather than being airy-fairy, this approach ensures that everyone is trained to understand how the organisation’s espoused values apply to very real everyday circumstances and decisions. Many organisations seek to adhere to a written set of corporate values, which might typically include:

- Put the customer first

- Treat people with respect

- Demonstrate integrity in all business dealings

- Treat the company’s money as though it is your own

Both everyday and major decisions can be seen in the light of these values. You need to be aware, however, that abiding by such values may require resolving inherent contradictions dependent on circumstances. For example, applying the fourth value, ‘Treat the company’s money as though it is your own’, may suggest that employees should choose the lowest cost alternative when procuring supplies and facilities from a range of bidders; however, doing so may involve a business practice that isn’t totally above board, thus breaching the value of conducting business with appropriate integrity. Posing such dilemmas to staff, asking them to consider and discuss the decisions they’d make, and then comparing their responses to those of the organisation in line with its espoused values, is a powerful means of driving the alignment of behaviour and decision-making across and throughout the enterprise.

In itself, alignment through commonly applied values is probably insufficient for a successful transformation – but it is a helpful step. Combined with the ‘harder’ (that is, more formalised) mechanisms for aligning objectives and activities, this approach can leverage the tightness of the overall alignment of the transformation effort across the organisation. Indeed, many transformations include a workstream focused on changing the culture of the organisation.

Weighing up the balanced scorecard

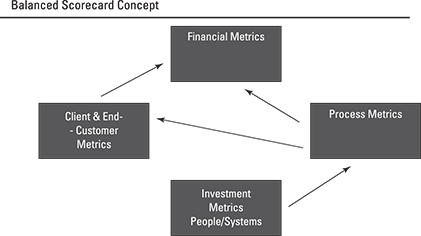

Chapter 5 looks at strategy maps and how they and the balanced scorecard can be used to review strategy, particularly in terms of its comprehensiveness and how well it’s described and articulated. Taken together, strategy maps and the balanced scorecard can illustrate how an overall objective can be decomposed into a series of subsidiary actions and objectives, each with their own measures and targets, and how these impact the various stakeholders represented by the financial, customer, process, and learning and growth quadrants, as illustrated in Figure 7-6.

Figure 7-6: The balanced scorecard.

The balanced scorecard concept can be applied across and down the organisation. The different parts of the enterprise each have their own scorecards linked to the organisation’s top level scorecard. Together with the associated strategy maps, this approach can be used to decompose and link the objectives of the different parts of the business.

This approach is very visual and has the advantage that all the objectives have to include suitable metrics and targets. Appropriately linked, the system of scorecards should enable a fair degree of alignment of objectives across the organisation.

The system of scorecards, however, is arguably more likely to be the result of an effective strategy deployment exercise than the vehicle for actually facilitating and undertaking it. That said, the process of developing the scorecards is likely to force the organisation to adopt an appropriate approach to strategy deployment.

Looking at management by objectives

Management by objectives (MBO) is a process of defining objectives so that management and employees agree to them and understand what they need to do to achieve them. It espouses the principle that, when people have actively participated in the setting of their objectives, they’ll be better motivated to achieve them. Appropriately cascaded throughout the organisation, MBO can enable a fair degree of alignment between the top-level objectives of the organisation and the different levels of management involved in delivering them. Managers can ensure that the objectives of their subordinates (and the groups of people they themselves manage) are linked to the organisation’s overall objectives.

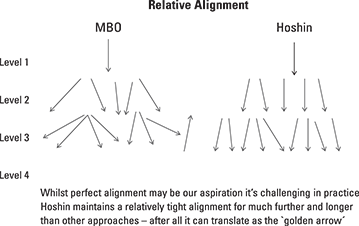

You can create objectives relating both to breakthrough and daily management. Although logical in theory, MBO in itself is unlikely to secure the degree of alignment of objectives being sought for your transformation efforts. By the time the objectives have cascaded a few times and reached people in different functions, small differences in alignment are likely to have multiplied and random impacts come into play unless the process has been subjected to stringent external moderation.

Understanding the notion of Hoshin

Hoshin Kanri (or simply Hoshin) is a strategic planning and management system, which was popularised in the late 1950s in Japan based on concepts developed by Professor Yogi Akao. Translated into English it can be read as ‘Golden Arrow’ or ‘Strategic Direction’. Hoshin was introduced into the US and Europe in the 1980s via organisations with Japanese subsidiaries such as Xerox and Hewlett-Packard, and its usage has accelerated more recently through its link with the Toyota Production System (TPS) and widespread application of Lean by that company. Hoshin is more typically referred to as ‘policy deployment’ or ‘strategy deployment’ in Western organisations. The notion of Hoshin is intended to help an organisation:

- Focus on a shared goal

- Communicate that goal to all leaders

- Involve all leaders in planning to achieve the goal

- Hold participants accountable for achieving their part of the plan

It assumes that daily controls and performance measures (daily management) are already in place. Hoshin planning involves the following seven steps:

- Identify the key business issues facing the organisation.

- Establish measurable business objectives that address these issues.

- Define the overall vision and goals.

- Develop supporting strategies for pursuing the goals (in the lean organisation, this strategy includes the use of lean methods and techniques).

- Determine the tactics and objectives that facilitate each strategy.

- Implement performance measures for every business process.

- Measure business fundamentals.

Closely associated with Hoshin is the catchball process (described in detail in Chapter 8) that tightly aligns the strategies, tactics and objectives down and across the organisation.

The separation of daily management and the focus on just a very few key objectives is consistent with the approach we recommend for planning and deploying transformation. Chapters 8 and 9 go into significantly greater detail on how Hoshin-based strategy deployment is applied in practice, and Figure 7-7 illustrates the different levels of strategic alignment that can be achieved using either MBO or Hoshin strategy deployment.

Figure 7-7: Tightness of alignment using MBO or Hoshin.

It makes good sense to review all the current initiatives and determine whether they’re all really necessary or appropriate at this time. Ideally, you should have done so as part of your assessment of your organisation’s readiness for transformation, but if not, consider undertaking a specific review. Our experience suggests that most organisations find that they can rationalise several initiatives, defer others, and close down some that are no longer really needed.

It makes good sense to review all the current initiatives and determine whether they’re all really necessary or appropriate at this time. Ideally, you should have done so as part of your assessment of your organisation’s readiness for transformation, but if not, consider undertaking a specific review. Our experience suggests that most organisations find that they can rationalise several initiatives, defer others, and close down some that are no longer really needed. You’re likely to have initiatives that remain important and which you want to continue that aren’t necessarily a part of the transformation as such. You need to consider the resourcing implications of continuing these initiatives in parallel with the intended transformation programme.

You’re likely to have initiatives that remain important and which you want to continue that aren’t necessarily a part of the transformation as such. You need to consider the resourcing implications of continuing these initiatives in parallel with the intended transformation programme. Resist scope creep and ensure that you review the scope of your transformation programme and its constituent projects on a regular basis with a view to maintaining or indeed reducing it rather than allowing it to creep upwards and outwards.

Resist scope creep and ensure that you review the scope of your transformation programme and its constituent projects on a regular basis with a view to maintaining or indeed reducing it rather than allowing it to creep upwards and outwards.